Abstract

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was passed in response to both the global pandemic’s immediate negative and expected long-lasting impacts on the economy. Under the Act, mortgage borrowers are allowed to cease making payments if their income was negatively impacted by Covid-19. Importantly, borrowers were not required to demonstrate proof of impaction, either currently or retrospectively. Exploring the economic implications of this policy, this study uses an experimental design to first identify strategic forbearance incidence, and then to quantify where the forborne mortgage payment dollars were spent. Our results suggest strategic mortgage forbearance can be significantly reduced, saving taxpayers billions of dollars in potential losses, simply by requiring a 1-page attestation with lender recourse for borrowers wishing to engage in COVID-19 related mortgage payment cessation programs. Additionally, we demonstrate the use of these forborne mortgage payments range from enhancing the financial safety net for distressed borrowers by increasing precautionary savings, to buying necessities, to equity investing and debt consolidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the first quarter of 2020, the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) spread from Asia throughout most of the world and unleashed its devastating impact on the United States in terms of both human casualties and economic consequences. To combat the spread of COVID-19, individual states adopted various levels of social distancing mechanisms, ranging from “shelter-in-place,” to “stay-at-home,” to full “lockdown” in the hopes of “flattening the curve.” While millions of employees were forced into a variety of remote working arrangements, for many industries working from home was simply not an option. As a result, the economy experienced mass layoffs, furloughs, and assorted other job, wage, and hour reductions. Unemployment filings rose dramatically, stock market volatility increased, equity values plummeted into bear market territory, and it soon became apparent something had to be done quickly to stave off further economic catastrophe.

In response, on March 27, 2020, an overwhelming bipartisan consensus in Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act amid growing concerns the spread of COVID-19 would keep businesses closed and the populace unemployed for an extended period. To prevent the economy from further deteriorating, the CARES Act authorized the direct injection of over $2 trillion into the economy. The Federal Reserve System (FED) subsequently provided additional support to financial markets through a variety of policy initiatives including asset purchases, credit facilities, and liquidity SWAPs. These combined stabilization activities increased the size of the FED balance sheet by over $3 trillion between the end of February and middle of June 2020.Footnote 1 Despite this well intentioned, openly transparent, and massive intervention, conventional wisdom maintained that many borrowers would not be able to make their required mortgage payments. To address this concern, the CARES Act made specific provisions to allow for all residential mortgages owned by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Veteran’s Administration (VA), and the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) to go into forbearance with significantly reduced (or entirely eliminated) negative consequences for both borrowers and lenders.

As of early 2020, the U.S. residential mortgage market consisted of approximately 50 million loans with a total outstanding mortgage balance of roughly $11 trillion (Hebron, 2020). CARES Act covered mortgages represent approximately 62% of that total. The average mortgage payment (principal, interest, taxes, and insurance) across these loans was roughly $1250 per month. Because servicers of these loans lack the labor force to receive, process, and evaluate the financial need of millions of forbearance applicants, the Act calls for borrowers to follow the “Honor Code” and only ask for mortgage forbearance if their income was adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

To alleviate borrower hesitancy to participate, “no fees, penalties, or interest beyond the amounts scheduled or calculated as if the borrower made all contractual payments on time and in full under the terms of the mortgage contract, shall accrue on the borrower’s account” (The CARES Act: P.L. 116-136 §4022) during an initial forbearance period of up to 6 months, which may be extended another 6 months. To engage in this mortgage forbearance program, all a borrower must do is stop paying their mortgage and notify their servicer. Lenders must (1) apply no penalties, late fees, or interest to the forborne payments,Footnote 2 (2) halt all evictions and foreclosure sales of borrowers, and (3) suspend reporting to credit bureaus of delinquency related to forbearance.Footnote 3

From a policy perspective, one major concern with this opportunity is that with such a low borrower cost, the game theoretic optimal solution is for nearly every borrower, including those who are not experiencing a COVID-19 related financial hardship, to self-select into the program, thus resulting in a moral hazard problem. One mechanism to help combat this potential free rider problem is to require forbearing borrowers to sign a 1-page document stating they are “experiencing a COVID-19 related decline in income.” After the pandemic is over, the servicer/lender may then perform a post-mortem review of all mortgage forbearance cases, and if the borrower is found to have participated without experiencing a COVID-19 related decline in income, stiff penalties could be enforced.Footnote 4

To assess the potential efficacy of such an approach, we conducted an experiment into whether a single page attestation to financial hardship with recourse would curb participation in the CARES Act forbearance program by those who do not need payment assistance. Our results document a statistically significant reduction in the forbearance program take-up rate conditional on such a required binding attestation. Alternatively stated, when borrowers know their feet will be held to the fire through a simple acknowledgement that free riding will not be tolerated and economic consequences will be imposed, we find a statistically significant reduction in people inappropriately receiving benefits from the CARES Act.

Moreover, it is instructive from a policy perspective to understand where this “extra” money gets allocated by those who misuse the program. If all such money is used in a manner consistent with what the government wants out of all the assistance programs, perhaps the misuse is not of great concern. If the uses were inconsistent with the overall policy design, it would suggest the programs are less effective than desired. While it is beyond the scope of our study to discern whether certain types of spending or investing are consistent with the Act, the results remain instructive to policymakers and academics as future programs are conceived and administered. Thus, we further explore questions such as whether some borrowers might choose to invest these funds into a potentially undervalued, yet highly volatile stock market in the hopes of making up for losses in other areas of their balance sheet. If such a gamble proves effective, the borrower reaps all the benefits and pockets any gains. On the other hand, if the market declines and the gamble does not pay off, the borrower simply defaults and walks away from (or modifies) the mortgage they can no longer afford, and the costs of the resulting bailout to lenders and/or taxpayers could potentially be many times greater. Here, the evidence reveals many borrowers would be willing to use their forgone mortgage payments to invest in the stock market (7.48%). Some indicated they would select low risk investments like TIPS/CDs (5.24%), while others reported they would use the money to pay down various consumer debts including student loans (3.80%), auto loans (4.00%), and credit cards (8.77%), which is analogous to using the CARES Act as a government sponsored debt consolidation program.Footnote 5 Interestingly, the largest shares of the forgone mortgage payments would purportedly be spent on “needs” like food and clothing (31.31%) or be stockpiled in cash (21.15%). While these are not the specifically designated uses of the bailout funds, they do represent allocations which strengthen the safety net of distressed borrowers, and in particular, the cash holdings may well act as precautionary savings and provide an important buffer against short-term income disruptions, while likely remaining readily available and accessible for when the forbearance period ends and all the monies must be repaid – or the loan modified.Footnote 6 Finally, we also demonstrate that a simple 1-page attestation can significantly reduce free-riders from using the program, while leaving it to policymakers to decide if these outcomes are consistent with overall policy goals.

Literature Review

Under the CARES ACT the decision to forbear one’s mortgage payments is now a choice requiring scant documentation and imposing little to no recourse. As such, it is entirely reasonable to imagine non-trivial numbers of individual borrowers electing to stop making their mortgage payments even when they can afford to continue paying. We term this behavior strategic forbearance.Footnote 7 While relatively little academic work to date has focused explicitly on the causes and consequences of mortgage forbearance,Footnote 8 a recent survey of mortgage borrowers by Lending Tree reveals 25% of their survey respondents applied for COVID-19 related mortgage forbearance, with 80% of those applications being approved. Furthermore, nearly 70% of those receiving forbearance indicated they would have been able to continue paying their mortgage without materially impacting their ability to pay other essential bills, thereby suggesting the strategic forbearance rate could be as high as 14%.Footnote 9 These estimates may be somewhat high as actual forbearance rates provided the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) are considerably lower. Specifically, as of mid-June 2020, the MBA reported 8.55% of all mortgage loans were currently in forbearance, with Ginnie Mae loans evidencing the highest forbearance rate (11.83%) of any individual product type.Footnote 10

On the academic literature side, the behavioral aspects and dimensions of these concerns naturally lead us to the related strand of strategic mortgage default literature that rapidly developed and blossomed in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-09.Footnote 11 Of note with respect to the current investigation, using a sample from Ireland, O’Malley (2018) finds mortgage defaults rose dramatically after a legal moratorium on evictions was imposed. This evidence strongly supports the existence of strategic decision making on the part of mortgage borrowers, and further evidences a moral hazard problem relating to this strategic decision. Similarly, Giné and Kanz (2017) conclude strategic defaults were the effectuated response after an Indian government bailout program, Chatterjee and Eyigungor (2015) discuss the role mortgage interest tax deductibility and delays in the foreclosure process play in a borrower’s decision to stop paying their mortgage, and Seiler (2015a) documents that fear of recourse is what stands between many borrowers and strategically defaulting. Taken together, these studies suggest borrowers respond strategically and directly to government policy interventions targeted at influencing mortgage market outcomes.

Additionally, mortgage modifications represent a related area where borrowers think strategically about mortgage default and other termination responses/outcomes. For example, in response to Countrywide’s class action settlement with delinquent mortgage borrowers, Mayer et al. (2014) document a new wave of defaults soon followed. The timing of this default wave strongly implies these borrower termination decisions were strategic in nature. Concerning the magnitude of this strategic component, Gerardi et al. (2017) estimate that as many as 38% of all financially capable borrowers failed to make required mortgage payments without the substitution effect of reducing consumption. To the extent CARES Act forbearance imposes even fewer costs on borrowers than strategic mortgage default, the potential for rampant strategic forbearance represents a potentially significant concern for mortgage servicers, underwriters, policymakers, and taxpayers.Footnote 12

Beyond mortgages, it is well-documented that individuals act strategically in practically every area of finance. Despite the strong evidence broadly confirming the importance of strategic borrower behavior across financial markets, many mortgage borrowers do not always choose to exercise their default option, even when given the financial incentive. Of note, Foote and Willen (2018) provide a recent summary of the mortgage default literature, examine various triggering events, and discuss why defaults are not more commonplace, even for those who are severely underwater. Interestingly, while Ghent and Kudlyak (2011) point to recourse as playing a major role in borrower defaults, Bhutta et al. (2017) discount the role of recourse. Instead, they provide arguments favoring the importance of emotional and behavioral considerations, such as being hesitant to breach a social contract and maintaining societal norms, in shaping borrower termination decisions. Guiso et al. (2013) compliment this latter line of thinking by associating and comparing strategic default decisions to views of morality and fairness, even asking borrowers if others in their social circles have defaulted. Seiler et al. (2012) take this idea even further by documenting how the social capital of having strategically defaulted can be viewed as shameful to some, but a badge of honor for others. No matter the investigation, Foote et al. (2008) discuss the difficulty policymakers face in determining who does and does not need financial intervention during trying times. While we fully understand, sympathize, and agree with this assessment, the purpose of the current investigation is first to identify some of the major ways people who strategically forebear allocate the dollars that would be spent on paying down their mortgage balance. We also seek to identify the profile of those who might use the funds and for which purposes, the risks their actions impose on our financial markets, and the potential resultant costs borne by taxpayers.

Methodology

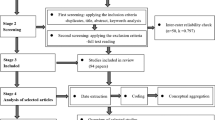

Studies examining the impact of major legislation are typically backward looking and effectively perform a post-mortem, identifying after the fact what went right and wrong. While this is a valid process to mitigate the chances of repeating the same mistakes in the future, an ideal approach is to compliment this econometric exercise with a forward-looking experiment designed to identify the full array of potential consequences before a policy is implemented (Baillon and Bleichrodt, 2015; Halevy 2007; Gneezy et al., 2006). This is the approach taken in the current investigation.

More specifically, our experimental participants (i.e., subjects) are randomly assigned to one of three main treatments. The first is the Honor Code category, a pool that reflects the current policy where borrowers simply stop paying their mortgage and notify their servicer. This pool represents the “honor system” approach reflected in the actual CARES Act guidelines. Given the experience of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, we hypothesize this approach will result in a moral hazard problem as many borrowers who do not face a financial hardship will still self-select into this pool, thereby resulting in an unnecessarily high number of free riders.

The second pool represents what we propose to be a simple deterrent to the moral hazard problem. We call this the Attestation with Recourse treatment. Under this scenario, to engage in mortgage forbearance all the borrower must do is sign a 1-page document stating they are “experiencing a COVID-19 related decline in income.” After the pandemic is over, the servicer/lender would retain the right to review all mortgage forbearance cases, and if the borrower was found to have participated without experiencing a COVID-19 related decline in income, stiff penalties would potentially be enforced. We intentionally do not elucidate on the details of what these penalties might entail, both because we do not want to restrict policymakers’ recourse, and because we do not want to alter (i.e., weaken/lower) borrower expectations as to the potential magnitude of such costs.Footnote 13

Signing a 1-page document before mortgage payment cessation in the case of a mailed application, checking a simple disclaimer box in the case of completing an on-line form, or taking 30 s to verbally agree to and confirm responsibility for falsely claiming a COVID-19 related decline in income all represent extremely low impediments for legitimately impacted borrowers to get the financial hardship relief they need. Yet, this simple check represents a potentially large reduction in the number of opportunistic free riders who might otherwise abuse an economic stimulus package.

Importantly, the CARES Act only dictates how FHA, VA, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac mortgages will be handled. While this currently represents a sizable (62%) share of all mortgages, the Act does not specify or even suggest how the remaining 38% of private label mortgages should be addressed. As such, every portfolio lender (and/or servicer acting on their behalf) is left up to their own devices in deciding what to do during this pandemic. Of note, one major U.S. bank has adopted the decision to require each borrower seeking mortgage forbearance to complete a full financial need application with the promise that a forbearance decision will be made within seven days of submission. Consistent with the CARES Act, the borrower must have experienced a COVID-19 related decline in income. Does such a waiting period and formal income disruption review materially impact program participation?

These three treatments represent the main foci of our investigation. Specifically, we first examine who would participate in a no strings attached forbearance such as that for which the CARES Act provides. Second, we then investigate whether adding a 1-page attestation with recourse mitigates the moral hazard problem by reducing the incidence of free riders who do not need financial assistance, but instead are simply acting opportunistically to take advantage of the stimulus package. Third, we explore how participation might differ if we required a one week waiting period while borrower forbearance applications were examined for financial need before allowing mortgage payment cessation.Footnote 14 Following Ke (2021), the exact wording of these main treatment effects is provided in the appendix.

After exploring the raw incidence of forbearance program participation alongside its drivers and mitigating factors, we next focus on what forbearing borrowers will do with the funds they no longer forward to their mortgage servicer. Of note, the stock market dropped precipitously when the pandemic reached the shores of the United States.Footnote 15 Volatility was at an all-time high as the market tried to find its bottom. At the time of data collection, the market had recovered some of its losses, yet remained far off its high from just one month earlier. This led many to wonder if the worst was over, and whether it was an opportune time to invest in relatively under-valued stocks.

At the end of the forbearance period, the CARES Act calls for all mortgage payments to either be paid in full or have the loan modified.Footnote 16 If a borrower is truly in need of financial relief, it is reasonable to suspect he may not have the cash needed to immediately make up all missed mortgage payments at the end of the forbearance period.Footnote 17 More directly, if he had ready access to sufficient cash reserves, why would he have needed the forbearance in the first place? As such, one potential policy concern is forbearing borrowers might take excessive risks with the funds they now have that would have gone towards paying the principal and interest on their mortgage.

The temptation to use government stimulus funds to invest in a volatile stock market is a major concern, because if the market did not recover, or worse yet continued to decline (perhaps precipitously), borrowers would be in no position to bring their mortgages back to current. In fact, their financial situation could be even worse, and they may not even have the wealth they saved by withholding their interim mortgage payments. As a result, the government’s bailout costs could become far greater. Loss aversion and a desire not to exist in the loss domain is a powerful behavioral modifier that can result in otherwise risk averse individuals acting in a risk-seeking fashion (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979).

Even if forbearing borrowers do not invest in the stock market, policymakers should still understand where else forbearing borrowers might allocate their newly found money. Therefore, we directly ask participants to share where they anticipate allocating this capital. To ensure both tractability and parsimony of responses, we provide 11 possible uses of the funds and ask respondents how they would allocate forborne mortgage proceeds across these groupings which range from hoarding cash, to buying necessary versus unnecessary assets, to paying off a variety of debts, to investing (either conservatively or speculatively).

Additional Variables

As considerable uncertainty and ambiguity surrounding COVID-19 remains, we test whether people’s behavior is a function of how long they believe this pandemic and corresponding forbearance period will last. Specifically, we randomize the expected duration, or length of forbearance, to range from one to 12 months. This uniformly distributed number is then imbedded into the experimental description and is part of all three main treatment effects. We also attempt to control for potentially important borrower specific attributes and beliefs. For example, consistent with Seiler (2016, 2017), we collect information on the borrower’s moral view of engaging in strategic forbearance when a hardship is not experienced. Additionally, we anticipate the longer someone has lived in a home, the less likely they will be to forbear both for financial reasons as well as emotional attachments to homes in which they have spent a greater portion of their life. With respect to political beliefs, given both the polarized nature of the current political climate and that are data are in an election year, we ask borrowers to self-identify the extent to which they tend to vote for Republican versus Democratic candidates.Footnote 18 Borrowers who view their homes as investments rather than consumption goods may well be more likely to engage in forbearance, while future home price expectations (over the next 12 months) may also influence forbearance proclivities.

Borrower behavior may also be affected if the pandemic has personally impacted the homeowner. Accordingly, we control for whether the borrower has an immediate family member who has contracted or is confident they have contracted (since many areas do not test all sick people), COVID-19. We then widen the reference group by asking if anyone in their close circle of friends has, or has strong reason to believe they have, contracted the virus. Again, ex-ante we expect closer personal experience with, or direct exposure to, the potentially stark negative realities of a situation may well alter and enhance perceptions of the severity of the pandemic, and thus increase forbearance program participation rates.

Financial literacy is also suspected to be predictive of borrower behavior, as those who feel more able to navigate these uncharted waters may feel they have (or may actually possess) more choices and options at their disposal (Dimmock et al. 2016; Zahirovic-Herbert et al. 2016; Lusardi and Mitchell 2014; Van Rooij et al., 2011; Guiso et al., 2008). Similarly, during the GFC, many borrowers defaulted on their mortgages and gained first-hand experience on what the process entails. Their experience gave them a front row seat in how mortgage payment cessation works. A subset of those borrowers defaulted by choice, in what was later termed “strategic mortgage default.” We collect information from participants with respect to these previous defaults and previous strategic defaults as both variables may influence their choices and decisions in the current crisis.

People’s choices are also often largely a function of their personality. Notably, Odean (1999) and Barber and Odean (2001) show overconfidence impacts decision-making in a number of financial situations. As such, we construct a proxy and control for potential borrower overconfidence. Consistent with Borghans et al. (2008), who offer a summary of the literature on personality traits and how they apply to behavioral economics, we also collect data on the Big 5 personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness. Finally, we collect an array of demographic data often included as part of mortgage market analyses. These borrower specific attributes include whether or not the respondent has at least one dependent child living in the home, gender, marital status, age, income, ethnicity, and educational attainment (which we group with our financial sophistication proxies).

Data

This experiment is carried out using the well-established on-line platform Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a subsidiary of Amazon used in countless empirical studies across a multitude of disciplines.Footnote 19 To test our central hypothesis, on April 13 and 14, 2020, drawing on a pool of homeowners who carry a mortgage, we collected data from 1690 borrowers across the country. Our participants come from all 50 states plus the District of Columbia. To ensure a clean sample, we establish several safeguards. To begin, we require all potential subjects possess at least a 95% approval rating from past participations in the MTurk system. To elaborate, after a person completes a “HIT” on MTurk, the “requester” must either approve or disapprove their submission. If there is any reason to doubt the integrity of the “worker,” the requester does not have to pay them and that worker is recorded as being disapproved.

Unbeknownst to the experimental borrower, we also place hidden timers on every page of the experiment allowing us to reasonably assess whether the subject has taken the time to read pertinent information needed to understand the scenarios and answer our questions accurately.Footnote 20 Further, to prevent robo-completion of the experiment, we ask two dummy questions at different points in the experiment. These simply involve asking the borrower to select a specific number we explicitly identify between 1 and 9. This allows for only a 1/81 (1/9 * 1/9) chance subjects are not reading our questions, but still manage to answer both dummy questions correctly through random guessing.

We also collect the latitude and longitude coordinates of where the borrower is located when completing the experiment and cross-reference that location to where they claim to live via a drop-down menu, first by state and then by city. These numbers are then cross-referenced against zip codes, self-reported elsewhere during the experiment. Given that we do not allow participant back-tracking, it is unlikely experimental participants will randomly complete these independent questions and have them align due to random chance.

Furthermore, MTurk workers are assigned a unique ID offering them anonymity from requesters yet holding them responsible for diligent work ethics. While we have no way of identifying these individuals, we are able to cross-reference their current responses against past responses from our prior experiments. For those borrowers who have appeared in our past pools, we look for flags and double-check to ensure their answers have not inexplicably changed from pool to pool. While it is conceivable previously constant characteristics like location (or reported gender) may have changed, age should certainly be universally tracked through time.

Finally, to encourage borrowers to fully engage in our experiment, we financially incentivize participants by paying them double if they answer enough questions correctly to rank in the top quartile of subjects.Footnote 21 These intricate steps are all taken to ensure our results are as complete, accurate, and insightful as possible. After evaluating all screens to ensure data accuracy, we are left with 1060 experimental observations with complete answers across questions and valid/matching responses across all accuracy inclusion criteria.Footnote 22

Results

Major Treatment Findings

Table 1 presents the univariate results from testing our central hypotheses. Specifically, Panel A reports the borrower’s stated intention to engage in forbearance ranging from 1 (definitely will CONTINUE paying my mortgage) to 7 (definitely will STOP paying my mortgage) if there is no screening of financial (income) hardship involved. A cursory glance immediately reveals many borrowers simply will (1) and will not (7) participate in this opportunity. Combining categories 6 and 7, 24.22% of our participants report they would likely stop paying their mortgage under such a scenario. This number, while very much in line with the previously reported Lending Tree survey results, is quite large, particularly if it is generalizable to the broader universe of all 50 million U.S. residential mortgage loans which account for approximately $11 trillion in financial capital.Footnote 23

Panel B of Table 1 reports similar information but employs our second pool of borrowers whose forbearance participation was conditioned on a required attestation of financial need with lender recourse. That is, before they are allowed to forbear, they are required to sign a 1-page document stating they are “experiencing a COVID-19 related decline in income.” It is further explained that “after the pandemic is over, the lender will review all mortgage forbearance cases, and if you are found to have participated without experiencing a COVID-19 related decline in income, stiff penalties will be enforced.” The purpose of this attestation with recourse is to weed out those who are looking to free ride on the government’s stimulus package, and thereby mitigate the potential bailout costs to U.S. taxpayers. This minor requirement results in a statistically significant (at the 99% confidence level) reduction in the number of borrowers who plan to forbear at all points along the mortgage payment cessation portion of the scale (6 and 7), reducing the total number of borrowers who would stop paying their mortgage from 24.22% to 15.85%, an 8.37% reduction.

Since some loans are not covered under the CARES Act, we investigate in Panels C & D how borrowers might respond under private label programs. More specifically, Treatment 3 in Table 1 is segmented into two panels. Panel C reports the number of borrowers who would forbear IF approved, whereas Panel D shows the necessary condition of first applying for forbearance eligibility. Recall, at least one major private label institution’s approach with borrowers is to require them to complete a financial hardship verification package. Within seven days, the servicer then notifies them if they are eligible to stop paying their mortgage. The average score associated with those who would apply is 3.70 (where 1 = will NOT apply; 7 = will apply). If a borrower is truly in financial need, submitting an application prior to initiating forbearance seems to represent a relatively minor hurdle.Footnote 24 That said, because the time involved in collecting one’s financial documents comes with potentially non-trivial or even substantial search costs, it may well mitigate the free rider problem and only remain attractive to those with a reasonable expectation of receiving payment cessation assistance. The results from Panels C & D suggest 25.32% of borrowers would apply for forbearance, and if approved roughly 18.41% would accept it.Footnote 25

Conceptually, it is important to note that there is no recourse to borrowers in either Treatment 1 or 3. In Treatment 1, they are automatically approved for forbearance, whereas in Treatment 3, they must apply. In neither scenario can they be argued to have engaged in technical/legal wrongdoing because they are fully welcome to participate. Instead, a reduction in income related to COVID-19 is either trusted (Treatment 1) or verified (Treatment 3). It is only in Treatment 2 where a borrower can retroactively be held responsible via a post-mortem lookback provision. As such, it is Treatment 2 that results in a statistically significant reduction in the number of borrowers who would strategically forbear and stop making their mortgage payments in the absence of a significant, pandemic related income disruption.Footnote 26

Allocation of Capital upon Forbearance

Seeking additional insight, Table 2 investigates where borrowers will allocate their would-be mortgage payments if they decide to forbear. These results are further segmented by treatment number and whether borrowers indicated they would versus would not continue to make their mortgage payments. Interestingly, 7.48% of these newly available funds would reportedly be invested directly into the stock market which has experienced unprecedented volatility since the outbreak of the pandemic.Footnote 27 While this potential capital infusion may be highly welcomed by equity market participants (and provide some measure of price support and stability), taxpayers bear the risk in that if the market does well, forbearing borrowers capture all the upside gains, while if the market falls, borrowers default and lenders (or taxpayers) bear the brunt of the financial consequences.Footnote 28On the other hand, 5.24% would reportedly be invested in much safer CDs, TIPS or T-Bills, while 21.15% of funds would be held in cash, presumably reflecting uncertainty surrounding how long this pandemic will restrict the ability to earn a living.Footnote 29 Similarly, the category receiving the greatest allocation of funds (31.31%) is that used to buy necessities such as food and clothing. While not directly related to housing market outcomes, these uses of funds do enhance the social safety net of potentially impaired borrowers and may well provide a needed buffer and level of support to at-risk individuals and communities. To the extent such allocations mitigate extreme financial hardship and facilitate successful long-run mortgage repayments and/or modifications, they may not represent an actual deadweight cost to this policy intervention.

In addition, some participants would re-allocate mortgage funds to various forms of consumer debt. The CARES Act was designed to ease the financial burden of citizens by softening their requirement to make mortgage payments, but we also find some of the money saved by missing mortgage payments will likely be spent to reduce debt in other areas of the consumer’s balance sheet. This leads to the question, “Is it fair to lenders/servicers that credit card companies, student loan sources, and other credit offering institutions like auto and furniture sales financiers are using the money lenders would have received in the form of mortgage payments to reduce their risk exposure?” This reallocation of funds fundamentally shifts the risk profile of these investments, and therefore the interest rates each party would have charged had they known ex-ante the way the government was going to handle this black swan event.

As a singular example, delaying mortgage payments not only increases the likelihood of eventual default (or, at a minimum, the need to modify the loan at the end of the forbearance period), but pushing the payments to a later point in time also increases the effective duration of the loan, making it more sensitive to changes in interest rates. Since interest rates have been reduced to near zero, it seems disproportionately likely they may well go up after the crisis is resolved. Taken together, these assertions suggest that when interest rates rebound, the market value of outstanding mortgages will decrease even further than what would have been observed had the CARES Act not been designed in this fashion. Conversely, with respect to other forms of consumer debt, by allowing missed mortgage payments to go toward paying down these competing balances, the CARES Act advantages credit card, auto loan, student loan, and other consumer credit issuers at the expense of mortgage lenders. In terms of economic magnitude, using the numbers from Table 2, amongst borrowers indicating they are likely to “stop paying” their mortgages, an estimated 24.82% (8.77% + 3.80% + 4.00% + 8.25%) of the forbearance proceeds will be reallocated toward reducing other debts.Footnote 30

Implications and Magnitude of Findings

Returning to the overall magnitude of our findings, suppose 5% of these reallocated cash flows ultimately end up in serious delinquency or default, and therein incur a loss rate conditional upon default of 40% (note: we view both of these estimates as conservative assumptions given that delinquency rates on all CARES Act covered products experienced both delinquency and loss rates significantly higher than these levels during the global financial crisis of 2008-09).Footnote 31 Under these assumptions, without intervention nearly $200 million of capital per month that would have been collected by mortgage lenders will never be recaptured. Our simple attestation approach could prevent approximately $50 million per month of these losses. That said, we readily acknowledge these numbers are highly speculative, as in these unprecedented times both default/delinquency rates and/or loss rates conditional upon default could skyrocket, or alternatively, future government assistance programs targeted at either distressed borrowers or mortgage lending institutions could significantly soften the economic impact.Footnote 32

Multivariate Findings

In many fields, experimental results are discussed only as they relate to univariate analysis since the environment is controlled for at the design level. Nevertheless, we recognize additional exogenous variables may well meaningfully impact our results. As such, we next introduce an array of potential explanatory variables. Table 3 reports descriptive summary statistics for the variables we, and/or others across the previous literature, have argued may impact mortgage forbearance proclivities. We report both overall summary statistics as well as results segmented by treatment group. P values correspond to one-way ANOVA tests of whether the means across all three treatment groups significantly differ.

Beginning with respondent attributes regarding economic expectations and personal beliefs, unique to this study is the finding that 39.06% of borrowers in our sample find engaging in strategic forbearance – the act of stopping mortgage payments even when the borrower can afford to continue paying – is immoral. Continuing, the vast majority of those in our sample view their home as more of a consumption good rather than as an investment, while our subjects are slightly bearish on future home prices in their city. Consistent with current national trends, there is a nearly even split across experimental participants with respect to political affiliation and ideology.

Turning to the depth of personal experience with, and/or exposure to, the pandemic, nearly 11% of participants have a family member who has been diagnosed with, or has good reason to believe they have contracted, the coronavirus, while 19% know of at least one person inside their close circle of friends who has been infected. In terms of financial sophistication, our pool of sample participants is deemed above average in terms of financial literacy and more highly educated (76.60% have completed at least a 4-year college degree) relative to both prior studies of mortgage market outcomes and society at large. Nearly 1 in 7 (or 14% of) borrowers in the sample have previously defaulted on a mortgage, with more than 1 in 6 of those defaults being strategic in nature.

From a behavioral perspective, 20.94% of our sample participants are deemed overconfident. Additionally, they lean towards being more conscientious and agreeable. Finally, a cursory review of their demographic profiles reveals our homeowners are broadly similar to those surveyed in previous studies in terms of income, ethnicity, and gender, with the exception that our participants are slightly younger (38.37 years old). Thus, taken together, we view our pool of experimental participants as being broadly reflective of the universe of U.S. residential mortgage borrowers.

Table 4 reports the results from two different regression specifications (OLS and Ordered Probit) where the dependent variable is a Likert scale measure of borrower self-reported likelihood of participating in a CARES Act related mortgage forbearance. This variable ranges from 1 if the borrower plans to definitely continue paying their mortgage to 7 if they definitely plan to stop paying their mortgage and exercise their strategic forbearance option. While OLS estimates are provided for consistency with the previous literature, we also estimate an Ordered Probit since the dependent variables are both ordinal and constrained. Not surprisingly, both models provide qualitatively similar results. Notably, the observed statistical significance on the Treatment 2 dummy variable confirms our univariate finding that the simple requirement of attestation with recourse results in a reduction in the incidence of strategic forbearance. In terms of economic magnitude, classification tests applying these estimated (Ordered Probit) coefficients to our actual sample respondent characteristics suggest our focal “Borrower Attestation with Recourse” approach fundamentally alters the predicted forbearance outcome for 6.23% (66 of 1060) of our sample borrowers. More specifically, 16 (of 347) borrowers exposed to Treatment 2 would likely have pursued forbearance had attestation not been required, while 50 (of 713) not exposed to the attestation mandate would likely have been dissuaded from forbearance had such a requirement been in place.Footnote 33 Turning to our control variables designed to capture differences in economic incentives and beliefs, strategic forbearance morality is quite robust and consistent with expectations in that those who find it morally objectionable are significantly less likely to forbear. Somewhat surprisingly, none of our remaining controls along this dimension, including Political Affiliation, exhibit statistically significant explanatory power. Thus, we conclude strategic borrower behavior during the crisis cuts across party lines, at least in terms of forbearance participation.

Turning to our second set of controls relating to financial sophistication and personal experience, our results suggest those borrowers with an immediate family member who has contracted the virus are significantly more likely to strategically forbear. However, if COVID-19 has only infected the borrower’s close circle of friends, it is not enough to significantly alter mortgage payment cessation behavior. Additionally, with respect to borrower specific behavioral attributes, three of the Big 5 personality traits are significant. Specifically, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism are positively associated with mortgage payment cessation. With respect to demographic attributes and controls, higher income borrowers, Caucasians, and women are significantly more likely to continue making their mortgage payments, possibly because they are simply more able to do so. On the other hand, neither age nor familial status appear to significantly influence forbearance probabilities.Footnote 34

Estimating the magnitude of these potential effects, if we were to apply these results to all mortgages, this could result in a reduction of 3.12 million (50 million * 6.23%) fewer mortgages going into forbearance, impacting almost $685.3 billion ($11 trillion * 6.23%) in loans. Given an average mortgage payment of approximately $1250 per month, this results in a reduction of $3.89 billion (50 million * $1250 * 6.23%) per month in lost payment revenues to lenders. If only applied to those mortgages explicitly covered under the CARES Act, the numbers would still result in 1.93 million (50 million * 6.23% * 62%) fewer mortgages going into forbearance, impacting roughly $424.89 billion ($11 trillion * 6.23% * 62%) in loans, and impacting capital flows to servicers by approximately $2.41 billion (50 million * $1250 * 6.23% * 62%) per month.

We next explore where forbearing borrowers will allocate their money if they stop paying their mortgage. Table 5 presents the results from the first stage of this analysis where the dependent variable in Column 1 is set equal to 1 (35.8% of subject respondents) if the borrower would invest any positive percentage of their forborne proceeds into the stock market, and 0 (64.2% of subject respondents) if the borrower would invest nothing into the stock market. Examining the determinants of this allocation decision, all Economics and Beliefs control variables except Number of Months are statistically significant. Specifically, those without a moral objection to strategic forbearance are more likely to invest in the stock market, as are both those who have been in their home the longest and those who view their home as more of an investment than a consumption good. Consistent with a bullish economic outlook, if the borrower believes home prices will increase over the next 12 months, they are also more likely to invest in the market. Interestingly, Republicans are significantly more likely to invest their forgone mortgage payments in the stock market than are Democrats. In light of the aforementioned emerging evidence on disparate behavioral responses to COVID-19 policy innovations across party lines, we do not find this result overly surprising.

With respect to our behavioral attributes, not surprisingly, more conscientious borrowers appear reluctant to divert forgone mortgage payments away from their expressly authorized purpose into speculative activities, while consistent with the notion that more neurotic borrowers prefer to avoid highly stressful situations, such borrowers are more reluctant to invest their newfound proceeds in the relatively volatile equity markets. Lastly, examining the financial sophistication and demographic controls, younger people, those who earn more and/or have completed college, and ethnic minorities are all also more likely to invest in the stock market.

Turning to alternative uses of the forborne cash flows, Column 2 explores what factors and attributes lead mortgage borrowers to divert these sums into paying off various other forms of debt. Following our previous analyses, we set the dependent variable equal to 1 (65.8% of subject respondents) if the borrower would divert any positive percentage of their forborne proceeds to the repayment of outstanding debts (i.e., pay down credit cards, student loans, auto loans, and/or other debts), and 0 (34.2% of subject respondents) otherwise. From a purely economic perspective, those same factors which lead wealth maximizing borrowers to divert forborne payments into the equity market provide similar incentives for borrowers to consolidate their debt away from relatively high cost products into lower cost alternatives. As such, it is entirely unsurprising that the directionality of all Economics and Beliefs attributes remain consistent, though admittedly exhibit reduced explanatory power and statistical significance, as we move from Column 1 to Column 2. Additionally, direct personal exposure to the consequences of this pandemic appears to motivate debt consolidation proclivities in an economically meaningful fashion. With respect to borrower attributes, only Financial Literacy, Conscientiousness, and Child Dummy exhibit robust statistical significance, with each of these relations potentially attributable to past choices, behaviors, and risk-aversion.

Finally, as the continuing global pandemic increases the economic uncertainty confronting millions of American families, many mortgage borrowers may rationally respond by using forborne mortgage proceeds as a source of precautionary savings. To explore this possibility, we define and identify borrowers with precautionary savings motives as those who would simply retain the forborne proceeds in cash (i.e., “Hold onto the money – don’t invest anywhere”) or cash equivalents (i.e., “Invest in a low risk instrument (like a CD, TIPS or T-Bills”). As before, in Column 3 we set the dependent variable equal to 1 (70.4% of subject respondents) if the borrower would allocate any positive percentage of their forborne proceeds along either of these two precautionary savings dimensions, and 0 otherwise. Consistent with our previous arguments, each of our Economics and Beliefs attributes continue to retain their previously observed sign patterns, though these relations now generally fail to exhibit statistical significance at conventionally accepted levels. Both our Financial Sophistication & Experience and Behavioral Characteristics similarly fail to provide statistically significant new insights, while from a Demographics perspective male and minority borrowers appear to be more likely to embrace precautionary savings motivations with respect to forbearance proceeds.

Conclusions

In response to the CARES Act, we suggest a very low-cost rider to the current policy, and document that it would likely result in significant taxpayer savings by reducing the number of free riders who participate in mortgage forbearance programs. Specifically, by simply requiring a 1-page borrower attestation (with recourse) that they are “experiencing a COVID-19 related reduction in income,” we observe a statistically significant and economically meaningful reduction in mortgage payment cessation.

We also examine where the money borrowers previously directed toward making mortgage payments would go if borrowers forbear their payments. Not surprisingly, the array of uses is quite large. Some borrowers will invest these proceeds in the stock market, thereby creating the potential for significant positive returns, but also exposing both themselves and their lenders to substantial risk. To the extent government programs backstop potential missed payments and/or lender losses, taxpayers may ultimately be on the hook for non-trivial sums. Other, more risk-averse borrowers may favor precautionary savings uses of the money and stockpile cash or invest in relatively low-risk assets. Lastly, one result of the forbearance program is the potential expropriation of wealth from mortgage owners/servicers to issuers of consumer debt such as credit cards, student loans, auto loans, and various other consumer debt obligations including even payday loans. To the extent mortgage borrowers use forbearance proceeds to pay-off these higher cost alternative debt obligations, they may well be acting in an economically rational, and both wealth- and utility-maximizing fashion. However, such actions, which essentially serve as a government sponsored debt consolidation program, increase both the leverage and duration of the underlying mortgage. The resulting value loss, in turn, falls directly on both mortgage servicers (who are potentially liable for a portion of missed borrower payments) and lenders (who ultimately fund the loan and bear the residual credit risk).

Beyond the attestation with recourse, or main treatment effect, we also find that a borrower’s view of morality surrounding strategic forbearance is a significant determinant of behavior. Similarly, how directly they are impacted by COVID-19, their individual personality, income, and ethnicity also influence reported behavioral intentions. Where borrowers would invest these forborne proceeds, and more specifically who is willing to invest these forborne mortgage payments in the stock market, is a function of individual borrower economic considerations and beliefs, experiences, and financial sophistication including morality, home tenure, future home price expectations, political affiliation, personal experience with the virus, and educational attainment. Conscientious and/or neurotic behavioral characteristics also influence such allocation decisions, as do a broad range of demographic variables and borrower specific attributes including age, income, and ethnicity.

Future Research

It is widely believed that despite the unprecedented scale and scope of the CARES Act mortgage market intervention, many borrowers will still not have the ability to repay all months of forgone mortgage payments associated with COVID-19 related income disruptions. Thus, a clear need exists to examine how to deal with loans that would go into default absent an alternative solution once the forbearance period ends. Accordingly, we propose an extension of the current investigation to pre-test a myriad of creative alternatives such as principal reduction, shared-appreciation mortgage characteristics, adding payments to the end of the mortgage, otherwise modifying the existing loan, and so forth. Moreover, since Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) have a differential ability to adopt these various programs, it makes sense to think of these solutions by institution. We propose this work begin immediately, as it will take time to ramp up eventually adopted programs. Additionally, once the pandemic is resolved, a post-mortem comparison of the alternative arrangements employed by private institutions is also warranted. We trust such comparisons will yield unique and key insights into both forbearance and modification strategies which prove effective at meaningfully shaping both borrower behavior and economic outcomes.

Notes

FED balance sheet information is obtained directly from weekly FED publication H.4.1 and is available online at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm (accessed: 1/7/2021). This $3 trillion expansion includes approximately $1.7 T in net Treasury security purchases, $450B in mortgage backed security purchases, an additional $450B in liquidity SWAPs (primarily with other central banks), $100B in additional repurchase agreements and direct loans, and $400B in other activities including new credit facilities authorized under the emergency lending provisions contained in Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. Many of these facilities, while not explicitly enumerated in the CARES Act, are supported by direct equity infusions or credit support provided the Treasury using funds allocated under this legislative action. See Cheng et al. (2020), Haas and Neely (2020), and Martin (2020a, 2020b) for further details on the magnitude and impacts of specific COVID-19 related FED interventions.

For example, assume a borrower with 20 years left on the life of their mortgage is scheduled to make a $3000 mortgage payment, where $2000 goes towards principal and $1000 goes towards interest. If the borrower goes into forbearance for 3 months, $9000 of obligations will have accrued. Under current GSE servicing guidelines (e.g., the “COVID-19 Payment Deferral” option), the $9000 in forborne payments may be added to the borrower’s payment obligations as a zero interest second mortgage, due in full at the earlier of the maturity of the existing mortgage term (e.g., in 20 years) or sale/refinancing of the mortgaged property. As such, while the borrower is indeed charged interest on the full borrowed amount - just as they were before the CARES Act - they are not being charged additional interest due to the CARES Act protected forbearance.

Given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic and associated economic collapse, many mortgage servicers were understaffed and ill prepared to deal with the sheer volume of inquiries they confronted. As a result, non-pecuniary costs of initiating a forbearance such as time spent waiting in a phone queue to speak with a servicing agent to provide notification of a borrower’s intent to forbear may well have been non-trivial.

If the borrower applies by phone, the conversation should only take 30 s. If completed via the Internet, a simple box would have to be checked; and if done in hard copy, a single 1-page document/disclosure would be required to be signed. In any case, this step should not represent a significant hurdle in the forbearance process. Employing the same basic logic and economic rationale underlying the current investigation, some lenders have recently begun requiring “COVID-19 Borrower Certifications” be signed at closing. These attestations attempt to limit forbearance options and impose penalties for misrepresenting a borrower’s financial situation. While the enforceability of such documents has yet to be fully determined, the emergence of such practices provides strong evidence that mortgage lenders and servicers are taking the potential threat of economic losses resulting from COVID-19 related borrower forbearance decisions quite seriously. See McCaffrey (2020) for further insight into these emerging disclosures.

While such allocations may not be an explicitly enumerated policy goal of the CARES Act, to the extent such transfers facilitate a substitution of high-cost debt for lower cost debt they could easily be both utility and wealth maximizing from a borrower’s perspective. For example, McCann (2020) reports the average credit card interest rate on existing accounts averaged 14.52%, while the rate for new offers was 17.89% as of late summer 2020. Similarly, Helhoski (2020) reports the average interest rate on all student loans outstanding is 5.80%, while Bankrate.com indicates average new car auto loans ranged from approximately 4.25% to 4.75% during the summer of 2020 depending upon the specific timing and maturity of the loan. Lastly, while the costs of consumer credit vary widely by loan type and borrower credit score, McGurran (2020) examines data from Experian and reports these loans recently averaged 9.41%. Thus, using forbearance proceeds to effectively consolidate these debts at the substantively lower outstanding mortgage interest rate represents a potentially valuable indirect benefit to many borrowers.

We readily acknowledge there is a fine line and even disagreement as to which consequences of the CARES Act were intended versus unintended. Since we cannot enter the minds of Congress members at the time of their deliberations, differentiating between the two is often difficult, if not impossible. To avoid confusion, throughout this paper we attempt to avoid normative assumptions as to the implicit purposes of this legislation, and instead focus on the tangible implications of the Act’s passage, regardless Congressional intent.

Interestingly, a recent study by Ganong and Noel (2020) suggests mortgage default almost always requires a triggering event (beyond negative equity). If we agree the pandemic is one such triggering event, it seems reasonable to expect to observe a relatively higher take-up rate during Covid-19.

For insightful work related to the economics of mortgage forbearance, see Springer and Waller (1993) and their related citations.

See Kapfidze (2020) for further insight on the Lending Tree survey results.

See DeSanctis (2020a, 2020b) for complete survey results. Applying Lending Tree’s estimated 70% strategic behavior rate to the MBA’s reported forbearance incidence of 8.55% implies a strategic forbearance rate of approximately 6%. By early November, forbearance rates had decreased to 5.67%, but remained significantly above average historic levels.

While the seminal works of Foster and Van Order (1984), Kau and Keenan (1995), and Deng et al. (2000) which helped introduce and popularize the use of option-based theoretical modelling approaches to the analysis and valuation of mortgages allow for strategic borrower behavior, prior to the GFC, the bulk of the work applying these models to actual market outcomes tended to focus on their direct economic, rather than behavioral, implications.

Mortgage servicers are required to advance payments to investors for up to 4 months when a borrower stops making payments, thus putting them at great financial risk if borrowers (strategically) forbear in great numbers.

Seiler (2015b) finds peoples’ fear of mortgage default related penalties far exceeded the actual recourse pursued by lenders.

Astute readers may notice this third treatment scenario offers a slightly different, multi-stage decision framework. Notably, while both our simple forbearance and forbearance with attestation alternatives require a single decision point for borrowers, the pre-qualification process adds an additional level of complexity. To the extent key borrower characteristics and/or attributes which influence forbearance decisions are also correlated with that borrower’s willingness to undergo the pre-qualification scrutiny process, our results may be biased, thereby hindering our ability to identify the true impact of this oversight mechanism.

On December 31st, 2019, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at 28,538.44, the S&P 500 closed at 3230.78, while the NASDAQ closed at 8972.60. By March 23rd, 2020, mere days before final passage of the CARES Act, these indices had fallen by 34.85%, 30.75%, and 23.54%, or to 18,591.93; 2237.40; and 6860.67, respectively.

At the time these data were collected, it was unclear exactly how these missed mortgage payments were to be resolved. Instead, the purpose of the CARES Act was to quickly offer relief to homeowners who faced an immediate spike in unemployment due to shelter-in-place orders. While forbearing borrowers have multiple options at their disposal, and details on exactly how to resolve missed payments most effectively are still being considered today, the aforementioned “COVID-19 Payment Deferral” option employed by both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac adds all forborne mortgage payments to the outstanding debt obligation as a zero-interest second mortgage (due at the earlier of the original loan’s maturity, or sale/refinance of the mortgaged property).

See Karty et al. (2020) for additional insight into the depth of these potential loan workout and modification challenges.

See Seiler (2018), Harrison et al. (2021), and Ke (2021) for recent examples. This data collection modality is particularly valuable during the current COVID-19 pandemic, as it is fully compliant with “social distancing” restrictions where people are not allowed to gather for a face-to-face experiment.

We subsequently cut the data by those who have been on the page for more than 10 s, 20 s, and 30 s. In testing our central hypotheses, the results are qualitatively very similar across these thresholds. As such, we base our results on the most restrictive (i.e., conservative) 30-s screen. Results from alternative cuts of the data are available from the authors upon request. If these screens are not effective at weeding out randomized responses, our results should tend to be biased towards findings of non-significance.

Participants are paid a base amount of $1.09, which is consistent with common practices on MTurk. The experiment typically takes 8-10 min to complete.

This 62.7% (1060/1690) inclusion rate (or, 1 - 62.7% = 37.3% attrition rate) is roughly comparable to previous studies using the MTurk platform. In general, our screens are slightly more rigorous than those imposed by prior investigations, thus yielding a slightly higher attrition rate, but (hopefully) more reliable and accurate responses.

Since only 62% of all mortgages technically fall under the CARES Act provisions, the “at risk” numbers may be somewhat lower at 31 million loans and $6.82 trillion. However, these still represent potentially staggering figures.

While we would expect such additional qualification oversight to deter potential strategic forbearers from taking advantage of the system, it is also possible such reviews would provide reluctant forbearers with the psychological justification to proceed with such actions (i.e., “if the bank signs off on it, it must be okay”). As a corollary, consider pre-qualification and pre-approval decisions for home buyers. Many prospective purchasers (and agents working on their behalf) use these lender assessments as guidelines, or anchors, as to what they may truly be able to afford.

Returning to our experimental design, these results clearly confirm that some borrowers (27.3% of sample respondents) who are pre-approved for forbearance may not actually stop making payments. Consistent with this notion, DeSanctis (2020b) reports nearly one-third of borrowers (31.6%) exiting forbearance between June and November of 2020 never missed an actual payment. On a related note, while within our experimental context applicant characteristics are implicitly assumed to remain constant, in practice, personal situations constantly evolve in a myriad of ways. For example, during the weeklong evaluation interval, potential forbearers may see close friends or family members contract (or recover from) the virus. They may be furloughed from, or recalled to, work. While such complications should not materially impact the validity of our experimental findings, they do influence the potential generalizability of our Treatment 3 conclusions. As such, throughout manuscript we focus the majority of our analysis on exploring the depth and implications of our focal Treatment 2 (borrower attestation) scenario.

While the lack of recourse along this dimension in the CARES Act is hypothesized to leave borrower preferences unchanged with respect to forbearance intentions, to the extent forbearance pre-approval reviews effectively reveal a borrower’s true financial position (e.g., lack of income disruption) their ability to strategically act on such preferences may be mitigated.

The percentage of all borrowers who would invest in stocks and bonds averages 7.80% across all (1060) borrowers and is statistically significantly different from zero at the 99% level (T-statistic = 16.179; p value = 0.000). When restricted to those borrowers indicating a high likelihood of forbearance (i.e., experimental responses 6 & 7; N = 205), this average falls to 7.48% but remains highly significant (T-statistic = 6.912; p value = 0.000). In comparing the mean allocation to stocks in Treatment 1 versus Treatment 2, the mean difference is only 0.008, which corresponds to a p value of 0.802. When comparing Treatment 1 to Treatment 3, the mean difference is only 0.0184, which has a p value of 0.435.

In fairness, it is also possible that some distressed borrowers who would otherwise be forced into defaulting on or modifying their original loan terms could be bailed out by positive gains on these speculative equity investments.

Cohen-Cole and Morse (2010) argue the desire for liquidity can result in people behaving strategically in this way.

As these alternative credit instruments likely have higher interest rates than the corresponding borrower’s collateralized mortgage, such debt consolidation may well lower overall financing costs for many borrowers.

For perspective, Le and Pennington-Cross (2021) report typical losses conditional on default of 42.3% to 48.3% depending upon carrying cost assumptions. Furthermore, DeSanctis (2020b) reports 1.9% of loans exiting forbearance between June 1st and November 1st 2020 incurred costly, negative termination events (e.g., short sale or deed in lieu), while another 30.4% are still active but have inflicted costs on lenders through loan modifications, loan deferrals, and/or partial loss claims.

For additional perspective on the potential costs of COVID-19 related mortgage delinquencies and policy interventions, see Karty et al. (2020).

This 6.23% marginal value is in concert with the aforementioned 6% strategic forbearance estimate derived by applying the Lending Tree survey results to actual forbearance levels. Marginal effects are slightly reduced when using alternative, less robust (e.g., OLS) model specifications, while estimated effects are slightly magnified when we relax our data screens and use more, though potentially less reliable, survey respondents.

We further bifurcate the sample into those observations seeded with an above average (median) pandemic duration and those exposed to a below average (median) or shorter pandemic duration estimate. While the coefficient estimates on the Treatment 2 dummy across these alternative sample cuts move in their anticipated direction (i.e., the coefficient estimate on the high duration sub-sample was more negative than the coefficient estimate on the low duration sub-sample), these differences are neither statistically nor economically significant. This finding is entirely consistent with Table 4, which reports a lack of significance on the number of months the pandemic is expected to last. We also split the sample by two measures of borrower sophistication: 1) their Financial Literacy Score, and 2) whether (or not) they earned a college degree. This subsample analysis reveals those borrowers who are either more educated and/or scored higher in terms of financial literacy (again, as measured by individual responses to five FINRA questions), were indeed less likely to forbear when required to sign the binding attestation. We appreciate an anonymous reviewer who suggested running these additional tests which proved insightful.

References

Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., & Yang, D. (2021). Polarization and public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. Working paper, NBER.

Anderson, A. (2021). Early evidence on social distancing in response to COVID-19 in the United States. Working paper, University of North Carolina-Greensboro.

Baillon, A., & Bleichrodt, H. (2015). Testing ambiguity models through the measurement of probabilities for gains and losses. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 7(2), 77–100.

Bankrate.com (2020). Current car loan interest rates. Bankrate.com (2 September 2020). https://www.bankrate.com/loans/auto-loans/current-auto-loan-interest-rates/. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

Barber, B., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 261–292.

Barrios, J., & Hochberg, Y. (2021). Risk perception through the lens of politics in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Working paper, University of Chicago.

Bhutta, N., Dokko, J., & Shan, H. (2017). Consumer ruthlessness and mortgage default during the 2007 to 2009 housing bust. Journal of Finance, 72(6), 2433–2466.

Borghans, L., Duckworth, A., Heckman, J., & Ter Weel, B. (2008). The economics and psychology of personality traits. Journal of Human Resources, 43(4), 972–1059.

Chatterjee, S., & Eyigungor, B. (2015). A quantitative analysis of the U.S. housing market and mortgage markets and the foreclosure crisis. Review of Economics Dynamics, 18(2), 165–184.

Cheng, J., Skidmore, D., & Wessel, D. (2020). What’s the fed is doing in response to the COVID-19 crisis? What more could it do? Brookings report: 6-12.

Cohen-Cole, E., & Morse, J. (2010). Your house or your credit card, which would you choose? Personal delinquency tradeoffs and precautionary liquidity motives. Working Paper, University of Maryland.

Deng, Y., Quigley, J. M., & Van Order, R. (2000). Mortgage terminations, heterogeneity and the exercise of mortgage options. Econometrica, 68(2), 275–307.

DeSanctis, A. (2020a). Share of mortgage loans in forbearance increases to 8.55%. Mortgage Bankers Association (15 June 2020). https://www.mba.org/2020-press-releases/june/share-of-mortgage-loans-in-forbearance-increases-to-855. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

DeSanctis, A. (2020b). Share of mortgage loans in forbearance decreases to 5.67%. Mortgage Bankers Association (9 Nov 2020). https://www.mba.org/2020-press-releases/november/share-of-mortgage-loans-in-forbearance-decreases-to-567-percent. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

Dimmock, S., Kouwenberg, R., Mitchell, O., & Peijnenburg, K. (2016). Ambiguity aversion and household portfolio choice puzzles: Empirical evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 119(3), 559–577.

Engle, S., Stromme, J., & Zhou, A. (2021). Staying at home: Mobility effects of COVID-19. Working paper, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Foote, C., Gerardi, K., & Willen, P. (2008). Negative equity and foreclosure: Theory and evidence. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 234–245.

Foote, C., & Willen, P. (2018). Mortgage-default research and the recent foreclosure crisis. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 10(1), 59–100.

Foster, C., & Van Order, R. (1984). An option-based model of mortgage default. Housing Finance Review, 3(4), 351–372.

Ganong, P., & Noel, P.J. (2020). Why do borrowers default on mortgages? A new method for causal attribution. Working Paper 2020-100.

Gerardi, K., Herkenhoff, K., Ohanian, L., & Willen, P. (2017). Can’t pay or won’t pay? Unemployment, negative equity, and strategic default. Review of Financial Studies, 31(3), 1098–1131.

Ghent, A., & Kudlyak, M. (2011). Recourse and residential mortgage default: Evidence from US states. Review of Financial Studies, 24(9), 3139–3186.

Giné, X., & Kanz, M. (2017). The economic effects of a borrower bailout: Evidence from an emerging market. Review of Financial Studies, 31(5), 1752–1783.

Gneezy, U., List, J., & Wu, G. (2006). The uncertainty effect: When a risky prospect is valued less than its worst possible outcome. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(4), 1283–1309.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2013). The determinants of attitudes toward strategic default on mortgages. Journal of Finance, 68(4), 1473–1515.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2008). Trusting the stock market. Journal of Finance, 63(6), 2557–2600.

Haas, J., & Neely, C. (2020). Central bank responses to COVID-19. Economic Synopses, 23.

Halevy, Y. (2007). Ellsberg revisited: An experimental study. Econometrica, 75(2), 503–536.

Harrison, D., Luchtenberg, K., & Seiler, M. J. (2021). Improving mortgage default collection efforts by employing the decoy effect. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, forthcoming.

Hebron, J. (2020). Size of U.S. mortgage market. The Basis Point, an official publication of the Mortgage Bankers Association. https://thebasispoint.com/size-of-u-s-mortgage-market-in-2020-january-edition/. Accessed 8 Jan 2020.

Helhoski, A. (2020). Current student loan interest rates and how they work. nerdwallet (3 September 2020). https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/loans/student-loans/student-loan-interest-rates#InterestRates1. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Kapfidze, T. (2020). LendingTree finds the majority of homeowners approved for a mortgage forbearance may not have needed one. LendingTree (18 May 2020). https://www.lendingtree.com/home/mortgage/majority-of-homeowners-approved-for-mortgage-forbearance-may-not-have-needed-one-study/. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

Karty, K., Hinkelman, D., & Ryan, S. (2020). Forbearance in the CARES Act: A review of issues, impact, and mitigation strategies. White Paper, Aspen Grove Solutions.

Kau, J., & Keenan, D. (1995). An overview of the option-theoretic pricing of mortgages. Journal of Housing Research, 6(2), 217–244.

Ke, D. (2021). Who wears the pants? Gender identity norms and intra-household financial decision-making. Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Le, B. & Pennington-Cross, A. (2021). Mortgage losses: Loss on Sale and holding costs. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, forthcoming.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44.

Martin, F. (2020a). The impact of the fed’s response to COVID-19 so far. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis -- On the Economy Blog. (16 June 2020). https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2020/june/impact-feds-response-covid19. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

Martin, F. (2020b). Economic realities and consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic - part I: Financial markets and monetary policy. Economic Synopses, 10.

Mayer, C., Morrison, E., Piskorski, T., & Gupta, A. (2014). Mortgage modification and strategic behavior: Evidence from a legal settlement with countrywide. American Economic Review, 104(9), 2830–2857.

McCann, A. (2020). What is the average credit card interest rate? WalletHub (24 August 2020). https://wallethub.com/edu/cc/average-credit-card-interest-rate/50841/. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

McCaffrey, O. (2020). Mortgage lenders ask home buyers to pledge keeping up payments. Wall Street Journal, 26 August, B1.

McGurran, B. (2020). What’s a good personal loan interest rate? Experian (27 January). https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/whats-a-good-interest-rate-for-a-personal-loan/. (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

Odean, T. (1999). Do investors trade too much? American Economic Review, 89(5), 1279–1298.

O’Malley, T. (2018). The impact of repossession risk on mortgage default. Working Paper, Central Bank of Ireland.

Painter, M., & Qiu, T. (2021). Political beliefs affect compliance with COVID-19 social distancing orders. Working paper, Saint Louis University.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212.

Seiler, M. J. (2018). Asymmetric dominance and its impact on mortgage default deficiency collection efforts. Real Estate Economics, 46(4), 971–990.

Seiler, M. J. (2017). Do liquidated damages clauses affect strategic mortgage default morality? A test of the disjunctive thesis. Real Estate Economics, 45(1), 204–230.

Seiler, M. J. (2016). The perceived moral reprehensibility of strategic mortgage default. Journal of Housing Economics, 32(June), 18–28.

Seiler, M. J. (2015a). Do as I say, not as I do: The role of advice versus actions in the decision to strategically default. Journal of Real Estate Research, 37(2), 191–215.

Seiler, M. J. (2015b). The role of informational uncertainty in the decision to strategically default. Journal of Housing Economics, 27(March), 49–59.