Abstract

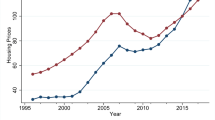

We use household-level data to study the causal effects of exogenous changes in housing wealth on health and the drug crisis in the US attributed to “deaths of despair”. We find that a one standard deviation positive shock in housing wealth increases the probability of an improvement in self-reported health (mental health) by 1.0 (1.10) percentage points, decreases the change in drug-related mortality rate by 4.3%, and has no effect on alcohol- or suicide-related deaths. The opposite effect also holds, such that a negative shock on wealth increases the probability of a decline in health. We also find that the impact of housing wealth on health varies across socioeconomic groups and is more pronounced in MSAs in which housing supply is more inelastic, which explains the differential effect of economic cycles across geographical areas. Our results suggest that housing-related policies could have important implications for general health outcomes as well as for the opioid crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hedegaard et al. (2017) document that the age-adjusted rate of drug-overdose has increased from 6.1 per 100,000 in 1999 to 19.8 per 100,000 in 2016.

Housing wealth misestimation is large, even with the proliferation of online real estate appraisals such as Zillow, as well as the existence of real estate municipal tax assessments and appraisals for extracting home equity value. Zillow documents that 45.6% (25.5%) of Zillows estimates are off by 5% (10%) or more (see https://www.zillow.com/zestimate). Moreover, the geographical variation is sizable. For example, 32.7% (14.7%) of Zillows estimates are off by 5% (10%) or more in Phoenix, while 62.1% (44.9%) of Zillows estimates are off by 5% (10%) or more in New York.

We define change in health outcome as the difference in health from two years after the unexpected wealth shock to the year of the wealth shock (i.e., when the household moves). This definition addresses a potential concern related to the fact that health shocks might trigger moving houses.

Adler et al. (1994); Backlund et al. (1999); Chandola (2000); Contoyannis et al. (2004); Cutler et al. (2010); Cutler et al. (2016); Feinstein (1993); Golberstein et al. (2016); Humphries and Van Doorslaer (2000); Lewis et al. (1998); Lleras-Muney (2005); Meara (2001); Meer et al. (2003); World Health Organization (2003)

Panel Study of Income Dynamics, restricted use dataset. Produced and distributed by the Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI (2017). The collection of data used in this study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant number R01 HD069609 and R01 AG040213, and the National Science Foundation under award numbers SES 1157698 and 1,623,684.

As we focus on the SRH of the head of the household, we drop observations that indicate a change in age of more than five years from one period to the next. We also remove observations with a negative change in age.

If a household sells its house and buys a new one between years t − 1 and t, we can only obtain its declared value of the previous house at time t − 1 (before selling it) and the transaction price of the new house at time t. This

In the PSID data there are many variables related to health outcomes. For instance, there is information about specific health conditions such as strokes, cancer, high blood pressure, and diabetes in PSID. Instead, we use the most common composite measures of health status in the health economics literature: (1) SRH, (2) total ADLs, and (3) mental ADLs. Moreover, we have long time series of the variables that we need to calculate SRH and ADLs in the PSID data.

The list of activities asked at the PSID are: bathing or showering, dressing, eating, getting in or out of bed or a chair, walking, getting outside, using the toilet, preparing own meals, shopping for personal toilet items or medicines, managing own money, using the telephone, doing heavywork, doing lightwork.

“Has a doctor ever told you that you have... Any emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems?”; “...loss of memory or loss of mental ability?”; “...a learning disorder?”

We also show that our results are robust to the control for portfolio choice characteristics at the household level such as the ratio of housing to net wealth and stock holdings over total net wealth. Table 7 in the Appendix reports these results.

An alternative approach could be to use interval regressions. Both methodologies produce coefficients of the same significance and order of magnitude, and have a similar fit in terms of log-likelihood. Although our empirical analysis is based on an ordered probit approach, we present results for both methodologies in the next section.

Our results are robust to the use of interval regressions.

The p-values for the t-tests on employment status, number of family members, and marital status are 0.28, 0.78, and 0.61.

Even if they do not sell, they would report a lower value of their house if they found that it was worth less because the question in PSID states “Could you tell me what the present value of this house (farm) is? I mean about what would it bring if you sold it today?”

Changes in the elasticity of supply at the MSA level are large in the cross-section but small in the time-series since we consider time lags of 2 years for changes in health outcomes in our panel. Recent studies that consider changes in the house price elasticity do not find relevant changes over short periods of time (e.g., Kirchhain et al. (2019)). Furthermore, there are no available time-varying measures of land elasticity at the MSA or city level that cover our period of study (1986–2015). For instance, Kirchhain et al. (2019) cover the time period 2014–2016.

When limiting the specification to only those who move, results are consistent since RHWM will only be different from zero for those households that move when they move.

Davidoff (2016) criticizes the use of housing-supply constraints as IVs for house prices in studies in which the dependent variable has an economic component, such as consumption growth, leverage, or investments, because some demand factors that could affect both house prices and the dependent variable of interest might have been omitted. This is not the case in our study, as the dependent variable is change in health status.

We estimate this model using maximum likelihood. The estimation is performed using the CMP user-provided package in STATA. See https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456882.html and Roodman (2009). This approach has been used extensively in the literature (e.g., Einav et al. (2012); Cullinan and Gillespie (2016)).

This choice of 33% divides our sample in about half, that is, 50% of the households in our sample live in the top 33% inelastic MSAs. Our results are robust to the choice of 33% as the threshold between elastic and inelastic cities. In the Appendix, we also report these results using a continuous measure of elasticity. These results are also robust, but less significant.

References

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G. H., & Price, B. (2016). Import competition and the great US employment sag of the 2000s. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S1), S141–S198.

Adler, N. E., Boyce, T., Chesney, M. A., Cohen, S., Folkman, S., Kahn, R. L., & Syme, S. L. (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist, 49(1), 15–24.

Agarwal, S. (2007). The impact of homeowners’ housing wealth misestimation on consumption and saving decisions. Real Estate Economics, 35(2), 135–154.

Anderson, R. N., Miniño, A. M., Hoyert, D. L., & Rosenberg, H. M. (2001). Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: Preliminary estimates. National Vital Statistics Reports, 49(2), 1–32.

Apouey, B., & Clark, A. E. (2015). Winning big but feeling no better? The effect of lottery prizes on physical and mental health. Health Economics, 24(5), 516–538.

Backlund, E., Sorlie, P. D., & Johnson, N. J. (1999). A comparison of the relationships of education and income with mortality: The national longitudinal mortality study. Social Science & Medicine, 49(10), 1373–1384.

Benítez-Silva, H., Eren, S., Heiland, F., & Jiménez-Martín, S. (2015). How well do individuals predict the selling prices of their homes? Journal of Housing Economics, 29, 12–25.

Bossaerts, P., & Hillion, P. (1999). Implementing statistical criteria to select return forecasting models: What do we learn? The Review of Financial Studies, 12(2), 405–428.

Brot-Goldberg, Z. C., Chandra, A., Handel, B. R., & Kolstad, J. T. (2017). What does a deductible do? The impact of cost-sharing on health care prices, quantities, and spending dynamics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(3), 1261–1318.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(49), 15078–15083.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2017). Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2017, 397–476.

Chandola, T. (2000). Social class differences in mortality using the new UK National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification. Social Science & Medicine, 50(5), 641–649.

Chaney, T., Sraer, D., & Thesmar, D. (2012). The collateral channel: How real estate shocks affect corporate investment. American Economic Review, 102(6), 2381–2409.

Contoyannis, P., Jones, A. M., & Rice, N. (2004). The dynamics of health in the British household panel survey. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 19(4), 473–503.

Corradin, S., Fillat, J. L., & Vergara-Alert, C. (2013). Optimal portfolio choice with predictability in house prices and transaction costs. The Review of Financial Studies, 27(3), 823–880.

Corradin, S., Fillat, J, L. & Vergara-Alert, C. (2017). Portfolio choice with house value misperception. Working papers 17–16, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Cullinan, J., & Gillespie, P. (2016). Does overweight and obesity impact on selfrated health? Evidence using instrumental variables ordered probit models. Health Economics, 25(10), 1341–1348.

Currie, J., & Madrian, B. C. (1999). Health, health insurance and the labor market. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 3309–3416.

Currie, J., Stabile, M., Manivong, P., & Roos, L. L. (2010). Child health and young adult outcomes. Journal of Human Resources, 45(3), 517–548.

Cutler, D, M., Lleras-Muney, A. & Vogl, T. (2008). Socioeconomic status and health: Dimensions and mechanisms (No. w14333). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w14333.

Cutler, D, M., Lange, F., Meara, E., Richards, S. & Ruhm, C, J. (2010). Explaining the rise in educational gradients in mortality (No. w15678). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cutler, D, M., Huang, W. & Lleras-Muney, A. (2016). Economic conditions and mortality: Evidence from 200 years of data (No. w22690). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cvijanović, D. (2014). Real estate prices and firm capital structure. The Review of Financial Studies, 27(9), 2690–2735.

Dávalos, M, E. & French, M, T. (2011). This recession is wearing me out! Health-related quality of life and economic downturns. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 14(2), 61–72.

Dávalos, M. E., Fang, H., & French, M. T. (2012). Easing the pain of an economic downturn: Macroeconomic conditions and excessive alcohol consumption. Health Economics, 21(11), 1318–1335.

Davidoff, T. (2016). Supply constraints are not valid instrumental variables for home prices because they are correlated with many demand factors. Critical Finance Review, 5(2), 177–206.

Einav, L., Finkelstein, A., Pascu, I., & Cullen, M. R. (2012). How general are risk preferences? Choices under uncertainty in different domains. American Economic Review, 102(6), 2606–2638.

Ettner, S. L. (1996). New evidence on the relationship between income and health. Journal of Health Economics, 15(1), 67–85.

Feinstein, J. S. (1993). The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: A review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly, 71, 279–322.

Fichera, E., & Gathergood, J. (2016). Do wealth shocks affect health? New evidence from the housing boom. Health Economics, 25, 57–69.

Fischer, M., & Stamos, M. Z. (2013). Optimal life cycle portfolio choice with housing market cycles. The Review of Financial Studies, 26(9), 2311–2352.

Follain, J. R., & Malpezzi, S. (1981). Are occupants accurate appraisers? Review of Public Data Use, 9(1), 47–55.

Gardner, J., & Oswald, A. J. (2007). Money and mental wellbeing: A longitudinal study of medium-sized lottery wins. Journal of Health Economics, 26(1), 49–60.

Golberstein, E., Gonzales, G. & Meara, E. (2016). Economic conditions and children’s mental health (No. w22459). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Goodman Jr., J. L., & Ittner, J. B. (1992). The accuracy of home owners’ estimates of house value. Journal of Housing Economics, 2(4), 339–357.

Hedegaard, H., Warner, M., Miniño, A. M. (2017). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. NCHS data brief, no 294. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. National Center for Health Statistics.

Himmelberg, C., Mayer, C., & Sinai, T. (2005). Assessing high house prices: Bubbles, fundamentals and misperceptions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 67–92.

Humphries, K. H., & Van Doorslaer, E. (2000). Income-related health inequality in Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 50(5), 663–671.

Iacoviello, M. (2012). Housing wealth and consumption. International encyclopedia of housing and home (pp. 673–678). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Idler, E. L., Kasl, S. V., & Lemke, J. H. (1990). Self-evaluated health and mortality among the elderly in New Haven, Connecticut, and Iowa and Washington counties, Iowa, 1982–1986. American Journal of Epidemiology, 131(1), 91–103.

Kaplan, G., Barell, V., & Lusky, A. (1988). Subjective state of health and survival in elderly adults. Journal of Gerontology, 43(4), S114–S120.

Kim, B., & Ruhm, C. J. (2012). Inheritances, health and death. Health Economics, 21(2), 127–144.

Kirchhain, H., Mutl, J., & Zietz, J. (2019). The impact of exogenous shocks on house prices: the case of the volkswagen emissions scandal. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 1–24.

Kish, L., & Lansing, J. B. (1954). Response errors in estimating the value of homes. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 49(267), 520–538.

Kuzmenko, T., Timmins, C. (2011). Persistence in housing wealth perceptions: evidence from the census data. Manuscript, Duke University.

Lettau, M., & Ludvigson, S. (2001). Consumption, aggregate wealth, and expected stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 56(3), 815–849.

Lewis, G., Bebbington, P., Brugha, T., Farrell, M., Gill, B., Jenkins, R., & Meltzer, H. (1998). Socioeconomic status, standard of living, and neurotic disorder. The Lancet, 352(9128), 605–609.

Lindahl, M. (2005). Estimating the effect of income on health and mortality using lottery prizes as an exogenous source of variation in income. Journal of Human Resources, 40(1), 144–168.

Lleras-Muney, A. (2005). The relationship between education and adult mortality in the United States. The Review of Economic Studies, 72(1), 189–221.

Long, M. J., & Marshall, B. S. (1999). The relationship between self-assessed health status, mortality, service use, and cost in a managed care setting. Health Care Management Review, 24(4), 20–27.

McClellan, M. B. (1998). Health events, health insurance, and labor supply: evidence from the health and retirement survey (pp. 301–350). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

McFadden, E., Luben, R., Bingham, S., Wareham, N., Kinmonth, A.-L., & Khaw, K.-T. (2008). Social inequalities in self-rated health by age: Cross-sectional study of 22 457 middle-aged men and women. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 230.

McInerney, M., Mellor, J. M., & Nicholas, L. H. (2013). Recession depression: Mental health effects of the 2008 stock market crash. Journal of Health Economics, 32(6), 1090–1104.

Meara, E. (2001). Why is health related to socioeconomic status? Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Meara, E. (2001). Why is health related to socioeconomic status? (No. w8231). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2011). House prices, home equity-based borrowing, and the US household leverage crisis. American Economic Review, 101(5), 2132–2156.

Mossey, J. M., & Shapiro, E. (1982). Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 72(8), 800–808.

Roodman, D. (2009). Estimating fully observed recursive mixed-process models with CMP. Center for Global Development Working Paper 168.

Ruhm, C. J. (2005). Healthy living in hard times. Journal of Health Economics, 24(2), 341–363.

Ruhm, C. J. (2015). Recessions, healthy no more? Journal of Health Economics, 42, 17–28.

Ruhm, C. J. (2018). Deaths of despair or drug problems? (No. w24188). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Saiz, A. (2010). The geographic determinants of housing supply. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 1253–1296.

Schwandt, H. (2018a). Wealth shocks and health outcomes: Evidence from stock market fluctuations. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(4), 349–377.

Schwandt, H. (2018b). Wealth shocks and health outcomes: Evidence from stock market fluctuations. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(4), 349–377.

Smith, J. P. (1999). Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relation between health and economic status. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(2), 145–166.

World Health Organization. (2003). Social determinants of health: the solid facts. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

Wu, S. (2003). The effects of health events on the economic status of married couples. Journal of Human Resources, 38(1), 219–230.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Cutler, Adriana Lleras-Muney, Ellen Meara, Seow Eng Ong, Albert Saiz, Judit Valls, Nancy Wallace, Xin Zou, and participants at the AREUEA-ASSA Annual Meetings 2019, Los Angeles Conference in Applied Economics (LACAE), Catalan Economic Society Conference 2019, AREUEA International Meetings 2019, IESE Business School and CaixaBank for their helpful comments.

Nuria Mas acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Ref. ECO2015-71173-P) and AGAUR (Ref. 2017-SGR-1244). She is the holder of the Jaime Grego Chair of Healthcare Management.

Vergara-Alert acknowledges financial support from the State Research Agency of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and the European Regional Development Fund (Ref. PGC2018-097335-A-I00, MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE) and AGAUR (Ref: 2017-SGR-1244).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jou, A., Mas, N. & Vergara-Alert, C. Housing Wealth, Health and Deaths of Despair. J Real Estate Finan Econ 66, 569–602 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-020-09801-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-020-09801-5