Abstract

This paper uses a novel dataset of capital expenditures on housing, to study how foreclosures affect capital expenditure investments in residential properties. Empirical analysis discovers that foreclosures negatively affect capital expenditure investment through the following channels: (1) individual homeowners reduce their capital expenditures when home prices fall and the likelihood of foreclosure increases; (2) lenders pursue a strategy of low investment in real estate owned (REO) inventories; (3) the reductions in capital expenditures generate a negative externality by creating a disincentive for other homeowners to spend on home improvements; and (4) a cluster of foreclosures further worsens the reduced investment situation. Purchasers of REO properties spend more on capital expenditures than those of non-REO properties in 1 year after sales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Keynes (1919), Krugman (1988) and Sachs (1990) show that heavy public debt loads reduce incentives for both public sector and private sector investments. For household finance decision, negative equity homeowners have less incentive to improve the property, since doing so makes the debt claim more secure and valuable without necessarily increasing the asset’s value to the owner.

Previous studies have used different data on sample periods and locations and different approaches to define foreclosures, distance radii, and time windows. But, in general, all of them have found a negative correlation between foreclosures and the market value of their neighboring properties.

Despite the lack of data on FSBO sales, Hendel et al. (2009) reports that MLS sales accounted for 86 % of all transactions sold from 1998 to 2005 in Madison, WI, a city near Milwaukee.

Amounts reported in the permit records are estimated costs provided by permit applicants. When a building permit is filed, the estimated cost of construction is entered on the application. The applicant may change the amount at any time. It is the responsibility of the applicant to submit the changes before issuance of a certificate of occupancy and/or before completion of construction. In practice, the assessor’s office flags unfinished permit activities and tracks the status of such flags by their expected completion dates to ensure permit activities are conducted as reported.

Harding, Rosenthal, and Sirmans (2007) estimated a 2.5 % overall rate of depreciation for the complete bundle of house attributes (including land). I have applied this overall estimate to all individual capital improvements. Capital expenditures may depreciate at a higher rate, but 2.5 % sets a boundary for this depreciation.

Major lenders sell their REO property via MLS listings. Merging sheriff’s deeds with MLS sales listings shows that 90 % of properties with a sheriff’s deed could be matched with an MLS sale.

The innermost ring with the shortest time radius includes in each direction the two or three nearest neighboring properties that have been sold shortly before potential buyers are visiting a subject property. The second ring could include foreclosures on the same block as the subject property. These foreclosures are unlikely to be visible from a subject property, but nevertheless, may be seen by prospective buyers visiting it. Foreclosures in the outer rings are not visible from the subject property, but may change buyers’ perceptions of the neighborhood or provide alternatives for buyers.

CDU and Grade are used by tax assessors in the City of Milwaukee. They are assigned the first time a property is inspected. Each time thereafter, when assessors review a property, they evaluate whether to keep or change its CDU. Grade rarely changes, because it reflects construction quality. The assessors do not change CDU without an inspection of the property. The Guide to the Property Assessment Process for Wisconsin Municipal Officials (http://www.revenue.wi.gov/pubs/slf/pb062.pdf) has specified the annual assessor requirements by assessment type and list when full evaluation is appropriate.

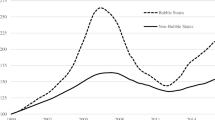

The S&P/Case-Shiller home indices methodology is available at http://us.spindices.com/index-family/real-estate/sp-case-shiller . The indices are calculated monthly, using a 3-month moving average algorithm. The index point for each reporting month is based on sales pairs accumulated in rolling 3-month periods. This averaging methodology is used to offset delays that can occur in the flow of sales price data from county deed recorders, to keep sample sizes large enough to create meaningful price change averages, and to mitigate concern over the volatility of the value of indices at the Zip code level.

The average age of properties in the sample is older than those in other studies. It is consistent with American Housing Survey (AHS), which shows that Milwaukee’s housing stock is older than the national average.

As discussed previously, endogeneity could be an issue because of the inclusion of foreclosure as an indicator variable in the model of Eq. (3). A Heckman selection model was estimated for a robustness check of this issue. In the first stage, the foreclosure likelihood was estimated with a probit model. The explanatory variables include property structure characteristics (\( {\mathrm{Z}}_{\mathrm{i}} \)), neighboring foreclosures (\( {\mathrm{NF}}_{\mathrm{itd}} \)), ZIP code price trend (\( {\mathrm{N}}_{\mathrm{i}} \)), ZIP code owner-to-tenant ratio (\( {\mathrm{OT}}_{\mathrm{i}} \)), and CBG fixed effect. The predicted foreclosure probability was then included in the second stage estimation for \( {\mathrm{Capex}}_{\mathrm{i}} \). The main findings remained the same under the Heckman model.

The supplemental result on the marginal effect in the Tobit model on the probability of being uncensored for capital expenditures before a sale and after a sale is available upon request.

The results remain the same under the following robustness checks: inclusion of CDU only; inclusion of both CDU and Grade; exclusion of both CDU and Grade.

The results remain the same when both age and age squared are included as explanatory variables.

The following robustness checks are also estimated: the inclusion of time fixed effect; the inclusion of the categorical variable of garage; the exclusion of CBG fixed effect. The main findings of the model were unchanged.

References

Campbell, J. Y., Giglio, S., & Pathak, P. (2011). Forced sales and house prices. American Economic Review, 101(5), 2108–2131.

Durlauf, S. (2003). Neighborhood effects. In J. V. Henderson & J.-F. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 4). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Gerardi, K. E., Rosenblatt, P.S. Willen, Yao, V. (2015). Foreclosure externalities: new evidence. Journal of Urban Economics, forthcoming.

Harding, J., Miceli, T. J., & Sirmans, C. F. (2000). Deficiency judgments and borrower capital expenditure. Journal of Housing Economics, 9(4), 267–285.

Harding, P., Rosenthal, S. S., & Sirmans, F. (2007). Depreciation of housing capital, capital expenditure, and house price inflation: estimates from a repeat sales model. Journal of Urban Economics, 61(2), 193–217.

Harding, J. P., Rosenblatt, E., & Yao, V. (2009). The contagion effect of foreclosed properties. Journal of Urban Economics, 66(3), 164–178.

Hendel, I., Nevo, A., & Ortalo-Magné, F. (2009). The relative performance of real estate marketing platforms: MLS versus FSBOMadison.com. American Economic Review, 99(5), 1878–1898.

Immergluck, D., & Smith, G. (2006a). The external costs of foreclosure: the impact of single-family mortgage foreclosures on property values. Housing Policy Debate, 17(1), 57–79.

Immergluck, D., & Smith, G. (2006b). The impact of single-family mortgage foreclosures on neighborhood crime. Housing Studies, 21(6), 851–866.

Keynes, J. M. (1919). The economic consequences of the peace. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe.

Krugman, P. R. (1988). Financing vs. forgiving a debt overhang. Journal of Development Economics, 29(3), 253–268.

Myers, S. C. (1977). Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics, 5(2), 147–175.

Pavlov, A., & Blazenko, G. W. (2005). The neighborhood effect of real estate maintenance. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 30(4), 327–340.

Rossi-Hansberg, Sarte, & Owens, III. (2010). Housing externalities. Journal of Political Economy, 118(3), 485–535.

Sachs, J. D. (1990). A strategy for efficient debt reduction. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(1), 19–29.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L. The Role of Foreclosures in Determining Housing Capital Expenditures. J Real Estate Finan Econ 53, 325–345 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-015-9505-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-015-9505-4