Abstract

We examine the use (and non-use) of list price information in the process of marketing commercial real estate. While housing market research suggests that list prices can serve as a strong anchor and/or signal, list price information is included in less than one-third of the commercial property sales and is less likely to be included as part of the sellers’ offering information for larger and more complex properties. Given the potentially powerful effect of list prices (first offers) on outcomes, the non-use of list price information is a puzzle. We speculate that the limited use of list prices may be due to the sellers’ interests in both maintaining their informational advantage and not truncating higher than expected offers, especially during periods of economic growth or with more complex properties. Using a two-stage selection correction model, we find that office properties which provide list price information are, on average, associated with lower price outcomes (ceteris paribus) and that these outcomes vary by price cohort and economic condition. It is important to note, however, that while these findings identify a correlation, they do not necessarily imply causation. Our results support the notion that asymmetric information and information signaling play a dominant role in explaining the sellers’ strategic non-use of list price information in the commercial real estate market and that the signaling effect is more pronounced in higher priced properties and during periods of strong economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

List prices and asking prices are used interchangeably in this paper.

In April of 2011, CoStar Group, Inc. announced that it was acquiring LoopNet, Inc. After a series of regulatory reviews, the transaction was completed on April 30, 2012 establishing a combined online commercial real estate data, analytics, and marketing resource.

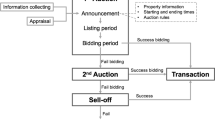

For example, the memorandum may indicate that “all interested parties must submit a non-binding Letter of Intent, by” a specified date. Generally, summarized information sheets known as “teaser” sheets or executive summaries are distributed to potential buyers through the brokers’ network prior to sending formal offering memoranda with required bid dates.

The offering may specify a list price, it may specify that the owner has not established a listing price, or it may omit any mention of list price information. Additional information, direct and indirect, may be provided in the listing that indicates possible seller motivations.

Related to this line of research, Kamis et al. (2004) find that final bids are influenced by the seller reference prices (reserve price) in their experimental research evaluating auction processes.

Note that the occupancy information in the data examined is not consistently coded. Vacant and very low occupancy buildings, when identified, were removed from the analysis.

The atypical sales such as 1031 tax-deferred exchanges, tenant purchases, distressed sales, sale leasebacks, or property shell sales, which are coded by CoStar as “detrimental condition” sales, represented approximately 7.7 % of the sales initially identified. Readers may be interested in noting that these observations were included in an earlier version of the paper. Their inclusion did not materially change the general results reported here when control variables were included in model estimates.

CoStar identifies 354 broker-defined office submarkets having transaction activity within the 24 metropolitan areas examined. The number of the submarkets in the metropolitan areas varies from two in Inland-Empire (California) to 39 in South Florida. Over 30 % of the submarkets reported less than 10 transactions during the study period. To maintain transaction activity within the submarkets and across the periods, submarkets with less than 25 transactions were identified and grouped with a larger submarket. Submarkets were grouped using the following criteria: (1) they were adjacent to each other; (2) their transaction prices per square foot were similar; and (3) they were located at similar distances from the metropolitan area’s central business district. This process resulted in the identification of 238 submarkets.

Construction quality is included in the probit model as a factor related to the use of a listing price. Price per square foot, PSF, can serve as a proxy for construction quality. However, including PSF in the first stage probit estimates of two-stage selection correction models (presented in “Selection-Corrected Model Estimates”) when the second stage includes both SQFT and lnSP causes potential problems with convergence the estimation results. To avoid this, price per square foot is specified as a categorical variable, PSFG, with values ranging from 1 to 12 (low to high) in all of the models estimated. PSFG is constructed to include approximately an equal number of observations in each category.

Inland Empire, commonly defined as the Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario MSA, is located east of the Los Angeles MSA.

The set of independent variables available for 4.1 and 4.2 are limited and additional property and seller characteristics (observed and unobserved) are likely to be important. To explore the potential significance of omitted property variables, unrelated to the time of sale, a subset of properties that sold twice is identified (1,849 obs.) and Model 4.2 re-estimated to include the variable (LIST1), where LIST1 is 1 if a listing price was used on the property’s previous sale, else 0. The estimated coefficient on LIST1 is not significantly different from zero at the 10 % level (β = 0.149; t = 1.61). This reinforces the explanatory strength of the limited set of factors included in 4.2. However, additional work is needed to investigate the role of the seller, broker, and other potentially important time varying characteristics on the use of list prices.

This model specification pools the observations in estimating the factor coefficients and in doing so it implicitly assumes that the estimated coefficient on each variable is constant across each of the other model factors (i.e., varying structure characteristics, time and markets). This is an important limitation of the model. Unfortunately, sufficient data are not available to reliably estimate cross-sectional results across each of the 24 markets for each period. To evaluate the sensitivity of LIST across varying economic conditions and structural cohorts, LIST (the key variable of interest) is interacted with the other variables of interest.

The marginal price of land ($10.92/sf) and the marginal price of the property ($113.64/sf), translate to a land-to-property price ratio of approximately 24.1 % assuming a floor area ratio (FAR) of 0.334 constructed from the median floor size and median land area (8.15/24.39).

In a meta analysis that looks at hedonic house price estimates, Sirmans et al. (2006) report that the estimated coefficient on age is −8.9 % for housing and that it can vary by as much as 1.4 % across regions.

Moody’s/RCA CPPI estimates that the annual price change for U.S. office properties were −19.2 %, −31.7 %, respectively, from December 2007 to December 2009.

Unfortunately, because commercial properties are often marketed directly to buyers and their advisors through the brokers’ network (sometimes using a bid request process), reliable time-on-market (TOM) information is not available. We suspect that the signaling is likely correlated (negatively) with TOM, but we are not able to control for this factor. In addition, information regarding specific lease terms and property occupancy rates in the dataset is not consistently reported. Observations with very low occupancy rates, if reported, have not been included in the analysis.

See, for example, Clapp and Giaccotto (1992) and Gatzlaff and Holmes (2012). To be representative, appraised values do not need to be reported at the property’s full (100 %) market value. The effects from the differences in market conventions (e.g., proportional values schemes) can controlled by including market area dummies within the regression model. However, the values within each market are assumed to be vertically and horizontally efficient.

The standard errors in the selection corrected model are adjusted and corrected t-stats reported.

We should mention that alternative model specifications that included time-on-market information were estimated with very little change in the coefficients of interest. The availability of the time-on-market data is quite limited and its reliability questionable; hence, it has not been reported.

Viewing the use of list prices, very broadly, as related to the use of reserves in auctions, these results are consistent with work in the auction literature. For example, Gan (2012) indicates that loss averse sellers will choose to set reserve prices (e.g., motivated sellers will choose to reveal list prices), and more sellers will prefer auctions without reserves when the market is hot (e.g., revealed list prices in a strong market provide clearer signals).

The price cohorts are selected to generally represent the non-institutional ($100,000–$10 million) and institution ($10 million to $500 million) categories. To mitigate estimation bias segmenting the data by assessed value was evaluated. However, because assessed values as a percentage of their market values vary substantially by location, this was not employed. Other alternatives were considered but segmentation by the approximate non-institutional and institutional price cohorts was determined to be most meaningful to the reader.

Results are reported for NYC, LA, CHI, and BOS. The transaction data were very limited in 2006 for DC and reliable estimates are not available.

References

Ariely, D., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2003). Coherent arbitrariness: stable demand curves without stable preferences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 73–105.

Bazerman, M., Neale, M., Valley, K., Zajac, E., & Kim, Y. M. (1992). The effect of agents and mediators on negotiated outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 53(1), 55–73.

Black, R., & Diaz, J. (1996). The use of information versus asking price in the real property negotiation process. Journal of Property Research, 13(4), 287–297.

Bokhari, S., & Geltner, D. (2011). Loss aversion and anchoring in commercial real estate pricing: empirical evidence and price index implications. Real Estate Economics, 39(4), 635–670.

Bucchianeri, G., & Minson, J. (2012). “A homeowner’s dilemma: Anchoring in residential real estate transactions.” Working Paper, University of Pennsylvania.

Camerer, C., & Loewenstein, G. (2004). Behavioral economics: Past, present and future. In C. Camerer, G. Loewenstein, & M. Rabin (Eds.), Behavioral economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Clapp, J. M., & Giaccotto, C. (1992). Estimating price indices for residential property: a comparison of repeat sales and assessed value methods. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87(418), 300–306.

Croson, R., & Mnookin, R. (1997). Does disputing through an agent enhance cooperation? experimental evidence. The Journal of Legal Studies, 26, 331–345.

Davis, D., & Holt, C. (1993). Experimental economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Furnham, A., & Boo, H. C. (2011). A literature review of the anchoring effect. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40, 35–42.

Galinsky, A., & Mussweiler, T. (2001). First offers as anchors: the role of perspective-taking and negotiator focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(4), 657–669.

Gan, Q. (2012). “Optimal selling mechanism, auction discounts, and time on market.” Real Estate Economics, Forthcoming.

Gatzlaff, D., & Holmes C. (2012). “Estimating transaction-based price indices of local commercial real estate markets using public assessment data.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, Forthcoming.

Geltner, D., Kluger, B., & Miller, N. (1991). Optimal price and selling effort from the perspectives of the broker and seller. Real Estate Economics, 19(1), 1–24.

Gilovich, T., Griffin, D., & Kahneman, D. (Eds.). (2002). Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Ecnometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Horowitz, J. (1992). The role of the list price in housing markets: theory and an econometric model. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 7(2), 115–129.

Kamis, M., Dreze, X., & Folkes, V. (2004). Effects of seller-supplied prices on buyers’ product evaluations: reference prices in an internet auction context. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(4), 622–628.

Knight, J. (2002). Listing price, time on market, and ultimate selling price: causes and effects of listing price changes. Real Estate Economics, 30, 213–237.

Knight, J., Sirmans, C., & Turnbull, G. (1994). List price signaling and buyer behavior in the housing market. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 9(3), 177–192.

Ling, D., Naranjo, A., Petrova, M. (2012). “Why do distant buyers pay more? search costs, behavioral biases, and information intermediary effects.” Working Paper.

Myerson, R., & Satterthwaite, M. (1983). Efficient mechanisms for bilateral trading. Journal of Economic Theory, 29(2), 265–281.

Northcraft, G., & Neale, M. (1987). Experts, amateurs, and real estate: an anchoring-and-adjustment perspective on property pricing decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39(1), 84–97.

Oesch, J., & Galinsky, A. (2011). “First offers in negotiations: Determinants and effects.” Working Paper, University of Toronto and Northwestern University.

Roth, A. (1995). Bargaining experiments. In J. Kagel & A. Roth (Eds.), Handbook of experimental economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Scott, P., & Lizieri, C. (2012). Consumer house price judgments: new evidence of anchoring and arbitrary coherence. Journal of Property Research, 29(1), 49–68.

Sirmans, G. S., MacDonald, L., Macpherson, D., & Norman Zietz, E. (2006). The value of housing characteristics: a meta analysis. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 33(3), 215–240.

Slovic, P., & Lichtenstein, S. (1971). Comparison of Bayesian and regression approaches to the study of information processing in judgment. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6(6), 249–744.

Strack, G., & Mussweiler, T. (1997). Explaining the enigmatic anchoring effect: mechanisms of selective accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(3), 437–446.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Valley, K., White, S., Neale, M., & Bazerman, M. (1992). Agents as information brokers: the effects of information disclosure on negotiated outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 51(2), 220–238.

Van Poucke, D., & Buelens, M. (2002). Predicting the outcome of two-party price negotiation: contribution of reservation price, aspiration price, and opening offer. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23(1), 67–76.

Wilson, T., & Houston, C. (1996). A new look at anchoring effects: basic anchoring and its antecedents. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 125(4), 387–402.

Yavas, A., & Yang, S. (1995). The strategic role of listing price in marketing real estate: theory and evidence. Real Estate Economics, 23(3), 347–368.

Yavas, A., Miceli, T., & Sirmans, C. F. (2001). An experimental analysis of the impact of intermediaries on the outcome of bargaining games. Real Estate Economics, 23(2), 251–276.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank discussants Tobias Muhlhofer and Abdullah Yavas for their comments, as well as participants at the FSU-UF Critical Issues in Real Estate Symposium hosted at the University of Florida; the AREUEA meeting in Washington, D.C.; and the ARES meeting in St. Pete Beach, FL where earlier versions of this paper were presented.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gatzlaff, D., Liu, P. List Price Information in the Negotiation of Commercial Real Estate Transactions: Is Silence Golden?. J Real Estate Finan Econ 47, 760–786 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-013-9435-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-013-9435-y