Abstract

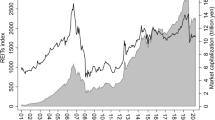

Local markets with tight land use controls result in prices rising relative to wages and affordability. Affordability is eased by unconventional but risky finance. Tight land use and loose financing in these renegade markets concentrates the impact of national or international shocks. A positive demand shock raises prices in these tight markets. If ongoing price momentum is expected, households switch to ownership and landlords reduce the rental stock. House prices, rents and occupancy rise and fall together in these markets. A five-equation sequential structure in land use, financial contracts, house prices, rents and vacancy for 17 United States cities confirms geographical concentration. Coastal California and South Florida are fundamentally risky markets. Discount rates there are three percentage points higher than the sample median. Two percentage points are attributable to land use and the other to unconventional finance. National and international financial crises are highly concentrated regionally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Over 2004–2010 San Francisco’s median house price from the National Association of Realtors was 4.4 times larger than that of Atlanta. The standard deviation of house prices in San Francisco was 3.8 times than in Atlanta. That house prices vary across localities is well-known, but the phenomenon extends to other assets. Localities with low population density such as the South have higher prices for publicly-traded stock (Hong, Kubik and Stein 2008) by having limited competition for investments.

The Mortgage Bankers Association of America reporting on the 2008 foreclosures indicated that 26% of all adjustable-rate mortgages in default were in California and another 16% in Florida. Arizona was in third place with 5% of these distressed loans. High-rate mortgages tied to the long end of the term structure are largely a California institution, accounting for nearly half the entire market, according to the tracker Loan Performance.

From the United States Department of Commerce C-20 New Construction series, 2006 marked a peak of housing construction since consistent records began in 1959. In 2006 more than two million housing units were started, compared with half a million in 1959. By 2007 starts had declined sharply until they fell below the half a million of 1959 by 2009 despite their being many more people.

Of the renegades, all are on the coasts except Phoenix. Two-thirds of the land in the metro Phoenix area is owned by the federal government land reserves for preservation, native people, or national parks. As with the other top-five markets, more than 60% of the land is not available for development.

The regional concentration of the financial crisis is not confined to the United States. Europe developed a similar crisis in its second-home markets of Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain. A potential emergence is in the recreational Asian markets of Hainan for China and Okinawa in Japan.

In Gyourko, Summers and Saiz (2008, Table 10) the rank order from most restrictive is Hawaii, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Maryland, Washington State, Maine and California. The index is a standard normal, with a mean of zero and standard deviation of one. Hawaii’s index is 2.36.

Las Vegas issued 20 times the per capita building permits of Boston. The 5,000 permits issued annually after 1995 in Boston were half the level of the 1970s. Supply restrictions were tightening, including minimum lot sizes, subdivision requirements and wetlands restrictions. It was when height and other land use controls were imposed that prices began to rise rapidly.

Green et al. (2005) estimate housing supply elasticities for metro areas. More than three-quarters of markets have supply elasticities greater than one. The most restrictive markets with near zero supply elasticities are on the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, notably Honolulu, Miami and Boston. Cheung et al. (2009) find that land use regulations are regressive and shifted demand to more adversely affect blacks.

The Wharton Regulation Index uses factor analysis and is standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, with a higher value connoting a more restrictive regulatory environment. In Glaeser et al. (2008) production cost is the R.S. Means construction estimate for a standard-quality 1,800 square foot unit with two adjustments. One is for land, at 20% of costs, and for gross contractor margins at 17% of costs. Saiz (2010) determines the proportion of land in waterways, highlands, marshes and other types that are not developable.

Associated valuations for utility level u are u 1(Z U ) and u 0(Z U ) where Z U includes the set of variables affecting upgrade when A* = u 1(Z U )−u 0(Z U ) ≥ 0.

Glaeser and Gyourko (2003) show that even in high-rise apartment and condo units in locations such as midtown Manhattan, construction costs are relatively moderate. Using R.S. Means data, the cost of construction for a high-rise residential tower of eight to 24 stories is no more in updated 2011 dollars than $200 per square foot, including a build-out allowance. In 1999 dollars they report $150 per square foot. For a 1,500 square foot unit the cost of construction is $300,000. This cost is less than half price is $300,000, less than half the prices of units delivered. The margin differential is attributed to land-use controls.

For Maricopa County, Arizona where Phoenix is located the largest single owner is the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. There are five Native American reserves and the Tonto National Reserve containing most of the remainder. These areas account for two-thirds of the metro land mass.

References

Bernanke, B. S., & Blinder, A. S. (1988). Credit, money and aggregate demand. American Economic Review, 78(2), 435–439.

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Julliard, C. (2008). Money illusion and housing frenzies. Review of Financial Studies, 21(1), 135–180.

Campbell, J. Y., & Shiller, R. J. (1988). Stock prices, earnings and expected dividends. Journal of Finance, 43(3), 661–676.

Carlino, G., & DeFina, R. (1998). The differential regional effects of monetary policy. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(4), 572–587.

Cheung, R., Ihlanfeldt, K., & Mayock, T. (2009). The incidence of the land use regulatory tax. Real Estate Economics, 37(4), 675–704.

Fratantoni, M., & Schuh, S. (2003). Monetary policy, housing, and heterogeneous regional markets. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 35(4), 557–589.

Gertler, M., & Gilchrist, S. (1994). Monetary policy, business cycles, and the behavior of small manufacturing firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(2), 309–340.

Glaeser, E. L., & Gyourko, J. (2003). The impact of building restrictions on housing affordability. Federal Reserve Board of New York Economic Policy Review, 9, 21–39.

Glaeser, E. L., Schuetz, J., & Ward, B. (2006). Regulation and the rise of housing prices in Greater Boston. Cambridge: Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston, Harvard University and Boston: Pioneer Institute for Public Policy Research.

Glaeser, E. L., Gyourko, J., & Saiz, A. (2008). Housing supply and housing bubbles. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 198–217.

Green, R. K., Malpezzi, S., & Mayo, S. K. (2005). Metropolitan specific estimates of the price elasticity of supply housing, and their sources. American Economic Review, 95(2), 334–339.

Guerrieri, V., Hartley, D. A., Hurst, E. (2010). Endogenous gentrification and housing price dynamics. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, No. 16237.

Gyourko, J., Saiz, A., & Summers, A. (2008). A new measure of the regulatory environment for housing markets. Urban Studies, 45(3), 693–729.

Hong, H., Kubik, J. D., & Stein, J. C. (2008). The only game in town: Stock price consequences of local bias. Journal of Financial Economics, 90(1), 20–37.

Kashyap, A. K., & Stein, J. C. (1995). The impact of monetary policy on bank balance sheets. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 42(1), 151–195.

Leamer, E. E. (2007). Housing is the business cycle. Proceedings, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 149–233.

Mayer, C. J., & Somerville, C. T. (2000). Land use regulation and new construction. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 30(6), 639–662.

McDonald, J. F., & Stokes, H. H. (2011). Monetary policy and the housing market. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics. doi:10.1007/s11146-011-9329-9.

Quigley, J. M., & Raphael, S. (2005). Regulation and the high cost of housing in California. American Economic Review, 95(2), 323–328.

Rosenthal, S. S., Duca, J. V., & Gabriel, J. V. (1991). Credit rationing and the demand for owner-occupied housing. Journal of Urban Economics, 30(1), 48–63.

Saiz, A. (2010). The geographic determinants of housing supply. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 1253–1296.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chinloy, P., Wiley, J.A. Renegade Asset Markets. J Real Estate Finan Econ 47, 197–226 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-011-9358-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-011-9358-4