Abstract

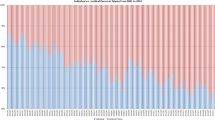

Many studies have hypothesized that the turn-of-the-month effect is caused by institutional investment. However, there is little evidence to support this hypothesis. This study provides an empirical test that measures the impact of the level of institutional investment on the turn-of-the-month effect using a sample of REITs over the period 1980 to 2004. We find that a significant change in the turn-of-the-month effect occurred following the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1993 which relaxed the requirements on the level of institutional investment in REITs. The evidence suggests that the dramatic rise in institutional holdings can account for a good part of this change. However, the impact of institutional investment may not be as large as some researchers have suspected. There is no evidence to suggest that institutional investment impacts returns on the day when the turn-of-the-month effect is most pronounced, suggesting that this calendar anomaly is not caused exclusively by institutional investors in the market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

International evidence for the turn-of-the-month effect has been discovered in Italy (Barone 1990), Japan (Ziemba 1991), the UK (Ziemba 1994), Finland (Martikainen et al. 1995), Australia, Canada, Germany and Switzerland (Cadsby and Ratner 1992). In addition, several studies find evidence for this effect in multiple countries over a consistent sample period (Agrawal and Tandon 1994 and Kunkel, Compton and Beyer 2003).

See Lo and MacKinlay (1990).

Footnote 18, p. 417

In fact, REITs are currently required to payout at least 90% of the net operating income (NOI) as dividends to shareholders. Wang, Erickson and Gau (1993) find that this requirement is often not binding, and the actual payout is about 165% of the NOI.

These factors include changes in market risk, the term structure of interest rates and unexpected inflation (see Chan et al. 1990).

See Ghosh, Miles and Sirmans (1996).

For example, see Merrill (1966).

French (1980) documents that the mean Monday return is significantly lower than during the rest of the week.

Even though the analysis begins in 1980 (coinciding with the availability of institutional ownership data) this construct includes REITs that entered the market prior to 1980.

These studies are primarily focused on the January effect, and generally find that the January effect tends to be driven by the performance of small firms. However, similar studies find that the turn-of-the-month effect is prevalent in the returns of both small and large firms.

To isolate short-run IPO effects we ran separate regressions omitting observations for the first quarter of a firm’s existence. The results of this approach are not shown, but are quite similar to the general results provided.

To test for the potential impact of survivorship bias, we ran separate regressions that included dummy variables and interaction terms to consider the impact of firms that were delisted during the sample period. Although the results are not shown, it is worth noting that we did not find a significant difference with respect to the impact of institutional investment and the turn-of-the-month effect for these firms.

For example, Jansen and de Vries (1991) argue that daily stock returns can be sufficiently modeled by a t distribution, which is fatter-tailed than the normal.

See, for example, Akgiray (1989) who uses a GARCH model which assumes conditional heteroskedasticity.

See Newey and West (1987).

See Gross and Steiger (1979).

Specifically, we use the GARCH process suggested by Taylor (1986).

Since institutional investment is reported quarterly, this variable reports the percentage of shares held by institutional investors at the beginning of the quarter for every day in that quarter.

The month of January and year 1980 are excluded.

See Kruskal and Wallis (1952).

In the interest of brevity, the estimates for the month and year dummy variables from the GLM model are not shown.

The H statistic is distributed c 2 with 1 degree of freedom (see Kruskal and Wallis 1952).

References

Agrawal A., Tandon K. (1994) Anomalies or illusions? Evidence from stock markets in eighteen countries. Journal of International Money and Finance 13:83–106

Akgiray V. (1989) Conditional heteroscedasticity in time series of stock returns: Evidence and forecasts. Journal of Business 62:55–80

Ariel R. (1987) A monthly effect in stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 18:161–174

Banz R. (1981) The relationship between return and market value of common stocks. Journal of Financial Economics 9:3–18

Barone E. (1990) The Italian stock market efficiency and calendar anomalies. Journal of Banking and Finance 14:483–510

Berkowitz S., Logue D., Noser E. (1988) The total cost of transactions on the NYSE. Journal of Finance 43:97–112

Blattberg R., Gonedes N. (1974) A comparison of the stable and student distributions as statistical models for stock prices. Journal of Business 47:244–280

Bohl, M., Gottschalk, K., & Pál, R. (2006). Institutional investors and stock market efficiency: The case of the January anomaly. MRPA Paper 677, University Library of Munich, Germany.

Bollerslev T. (1986) Generalized autoregressive conditionally heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics 31:307–327

Booth G., Kallunki J., Martikainen T. (2001) Liquidity and the turn-of-the-month effect: evidence from Finland. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 11:137–146

Cadsby C., Ratner M. (1992) Turn-of-the-month and pre-holiday effects on stock returns: Some international evidence. Journal of Banking and Finance 16:497–509

Chan S., Hendershott P., Sanders A. (1990) Risk and return on real estate: Evidence from equity REITs. Real Estate Economics 18:431–452

Chan S., Leung W., Wang K. (2004) The impact of institutional investors on the Monday seasonal. Journal of Business 77:967–986

Chan S., Leung W., Wang K. (2005) Changes in REIT structure and stock performance: Evidence from the Monday stock anomaly. Real Estate Economics 33:89–120

Colwell P., Park H. (1990) Seasonality and size effects: The case of real-estate-related investment. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 3:251–259

Connors D., Jackman M., Lamb R., Rosenberg S. (2002) Calendar anomalies in the stock returns of real estate investment trusts. Briefings in Real Estate Finance 2:61–71

Downs D. (1998) The value in targeting institutional investors: Evidence from the five-or-fewer rule change. Real Estate Economics 26:613–649

Engle R. (1982) Autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity with estimates of the variance of U.K. inflation. Econometrica 50:987–1008

Fama E. (1965) The behavior of stock prices. Journal of Business 38:34–105

French K. (1980) Stock returns and the weekend effect. Journal of Financial Economics 8:55–69

Gallagher D., Pinnuck M. (2006) Seasonality in fund performance: An examination of the portfolio holdings and trades of investment managers. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 33:1240–1266

Ghosh C., Miles M., Sirmans C. F. (1996) Are REIT stocks? Real Estate Finance 13:46–53

Gillan S., Starks L. (2000) Corporate government proposals and shareholders activism: The role of institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics 57:275–305

Griffiths M., Winters D. (2005) The turn-of-the-year in money markets: Tests of the risk-shifting window dressing and preferred habitat hypotheses. Journal of Business 78:1337–1364

Gross S., Steiger W. (1979) Least absolute deviation estimates in autoregression with infinite variance. Journal of Applied Probability 16:104–116

Hensel C., Ziemba W. (1996) Investment results from exploiting the turn-of-the-month effects. Journal of Portfolio Management 22:17–23

Jansen D., de Vries C. (1991) On the frequency of large stock returns: Putting booms and busts into perspective. Review of Economics and Statistics 73:18–24

Jones, C. M. (2002). A century of stock market liquidity and trading costs. Working Paper.

Jordan S., Jordan B. (1991) Seasonality in daily bond returns. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 26:269–285

Khoo T., Hartzell D., Hoesli M. (1992) An investigation of the change in real estate investment trust betas. Real Estate Economics 21:107–130

Kruskal W., Wallis W. (1952) Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 47:583–621

Kunkel R., Compton W. (1998) A tax-free exploitation of the turn-of-the-month effect: C.R.E.F. Financial Services Review 7:11–23

Kunkel R., Compton W., Beyer S. (2003) The turn-of-the-month effect still lives: The international evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis 12:207–221

Lakonishok J., Smidt S. (1988) Are seasonal anomalies real? A ninety-year perspective. Review of Financial Studies 1:403–425

Lesmond D. A., Ogden J. P., Trzcinka C. A. (1999) A new estimate of transaction costs. Review of Financial Studies 12:1113–1141

Lo A., MacKinlay A. (1990) Data-snooping biases in tests of financial asset pricing models. Review of Financial Studies 3:431–467

Mandelbrot B. (1963) The variation of certain speculative prices. Journal of Business 36:394–419

Martikainen T., Perttunen J., Ziemba W. (1995) Finnish turn-of-the-month effects: Returns, volume and implied volatility. Journal of Futures Markets 15:605–615

Merrill A. (1966) Behavior of prices on wall street. The Analysis Press, Chappaqua, NY

Morey M., O’Neal E. (2006) Window dressing in bond mutual funds. Journal of Financial Research 29:325–247

Newey W., West K. (1987) A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55:703–708

Ogden J. (1990) Turn-of-month evaluations of liquid profits and stock returns: A common explanation for the monthly and January effects. Journal of Finance 4:1259–1272

Penman S. (1987) The distribution of earnings news over time and seasonalities in aggregate stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 18:199–228

Redman A., Manakyan H., Liano K. (1997) Real estate investment trusts and calendar anomalies. Journal of Real Estate Research 14:19–28

Ritter J. (1988) The buying and selling behavior of individual investors at the turn of the year. Journal of Finance 43:701–717

Rozeff M., Kinney W. (1976) Capital market seasonality: The case of stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 3:379–402

Smith K., Shulman D. (1976) The performance of equity real estate investment trusts. Financial Analysts Journal 32:61–66

Subrahmanyan A. (2007) Liquidity, return and order-flow linkages between REITs and the stock market. Real Estate Economics 35:383–408

Taylor S. (1986) Modeling financial time series. Wiley, New York, NY

Wang K., Erickson J., Gau G. (1993) Dividend policies and dividend announcement effects for real estate investment trusts. Real Estate Economics 21:185–201

Wang K., Erickson J., Gau G., Chan S. (1995) Market microstructure and real estate returns. Real Estate Economics 23:85–100

Zerbst R., Cambon B. (1984) Real estate: Historical returns and risks. Journal of Portfolio Management 10:5–20

Ziemba W. (1991) Japanese security market regularities: Monthly, turn-of-the-month and year, holiday and golden week effects. Japan and the World Economy 3:119–146

Ziemba W. (1994) World wide security market regularities. European Journal of Operational Research 74:198–229

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiley, J.A., Zumpano, L.V. Institutional Investment and the Turn-of-the-Month Effect: Evidence from REITs. J Real Estate Finan Econ 39, 180–201 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-008-9106-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-008-9106-6