Abstract

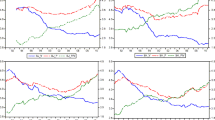

This paper studies actual (real) house prices relative to fundamental (real) house values in New Zealand for the period 1970–2005. Utilizing a dynamic present value model, we find disparities between actual and fundamental house prices in the early 1970s and 1980s and from 2000 to date. We model the bubble component that is related to fundamentals (the intrinsic component), making it possible to highlight whether a bubble still exists after that component is accounted for. We then analyze any remaining bubble to detect any momentum behavior. Much of the overvaluation of the housing market is found to be due to price dynamics rather than an overreaction to fundamentals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These occurred in 1974Q3, 1984Q2, 1989Q1 and 1997Q3.

Due to the high incidence of fixed rate mortgages (typically of 2 to 5 years) in New Zealand, an increase in interest rates may take some time to impact fully on market prices.

New Zealand households hold less than 4% of total assets in direct holdings of domestic and foreign equities; in the USA, the comparable figure is 17%. The equivalent figures for indirect ownership of equities (% of GDP) are 4 and 35% respectively (Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor’s speech 2006).

Meen (1996) for example shows that a range of policy shocks can cause a shift in the relationship between prices and income over the long-term, particularly if the user cost of capital is constrained to be constant.

No consistent time series of equity data is available for New Zealand prior to this date.

Due to the lack of rental data, it is common in the real estate literature to add 5% per annum to the price index to proxy the gross index.

The nominal annual capital gain and total return to equity over this sub-period was 1.6 and 6.84%, respectively.

The VAR coefficient estimates (not reported) indicate one-way causality from income growth to the house price to disposable income ratio and dual causality between the price income ratio and house price return variance.

Inflation peaked in 1980 at 18.4% and was 15.2% in 1981. The 5 years preceding 1980 had inflation of 13.0, 17.6, 13.2, 14.7 and 10.6%. Unemployment rose steadily between 1978 and 1980, in 1981 it was 3.1%. This latter figure is to be compared with the maximum between 1960 and 1977 which was 0.6%. Employment growth was actually negative for 1981, only the third negative figure in 21 years. The 6 years from 1976 through till the end of 1981 were poor for real output growth, over the period it only averaged 0.5%. Real wages were at a level slightly below that of 1972 (Dalziel and Lattimore 2001). Real disposable income growth was also negative in 1980 and again during 1982 and 1983.

Over the period 1988Q1 to 2005Q4, the New Zealand real income return was 5.22% compared to 2.36% for the USA, 3.28% for the UK, and 4.02% for Australia (Ibbotson Associates database).

If bubbles are uncorrelated with fundamentals, in order to be arbitrage free they must be expected to grow at a rate of 1 + ρ per period and the bubble and fundamentals will be driven apart at an explosive rate.

Momentum in the changes in house prices can also result from momentum in the changes in fundamentals.

The fact that sellers of the residential housing stock tend to use local prices as a benchmark also perpetuates this process.

We also experimented with measures of conditional variance derived from various specifications of GARCH-type models of housing returns. However, the results were very similar to those reported below.

References

Abel, A. B. (1991). The equity premium puzzle. Business review. September/October, (pp 3–13). Philadelphia: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Abraham, J. M., & Hendershott, P. H. (1996). Bubbles in metropolitan housing markets. Journal of Housing Research, 7(2), 191–207.

Ackert, L. F., & Hunter, W. C. (1999). Intrinsic bubbles: The case for stock prices: Comment. American Economic Review, 89(5), 1372–1376.

Ayuso, J., & Restoy, F. (2003). House prices and rents: An equilibrium asset pricing approach. Working paper 0304, Madrid (Spain): Bank of Spain.

Balmer, D. (2004). The truth about residential property investment. Auckland (New Zealand): Reed Publishing.

Barberis, N., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1998). A model of investor sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics, 49(3), 307–343.

Benjamin, J. D., Chinloy, P., & Jud, G. D. (2004). Real estate versus financial wealth in consumption. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 29(3), 341–354.

Black, A., Fraser, P., & Groenewold, N. (2003a). How big is the speculative component in Australian share prices? Journal of Economics and Business, 55(2), 177–195.

Black, A., Fraser, P., & Groenewold, N. (2003b). U.S. stock prices and fundamentals. International Review of Economics and Finance, 12(3), 1–23.

Black, A., Fraser, P., & Hoesli, M. (2006). House prices, fundamentals and bubbles. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33(9), 1535–1555.

Bollard, A., Lattimore, R., & Silverstone, B. (1996). Introduction. In B. Silverstone, A. Bollard, & R. Lattimore (Eds.), A study of economic reform: The case of New Zealand. Amsterdam (The Netherlands): Elsevier.

Bourassa, S., & Hendershott, P. (1995). Australian capital city real house prices, 1979–1993. Australian Economic Review, 111, 16–26.

Bourassa, S. C., Hendershott, P. H., & Murphy, J. (2001). Further evidence on the existence of housing market bubbles. Journal of Property Research, 18(1), 1–19.

Boyle, G. W. (2005). Risk, expected return, and the cost of equity capital. New Zealand Economic Papers, 39(2), 181–194.

Campbell, J. Y., & Shiller, R. J. (1987). Cointegration and tests of present value models. Journal of Political Economy, 95(5), 1062–1088.

Campbell, J. Y., & Shiller, R. J. (1988a). The dividend-price ratio and expectations of future dividends and discount factors. Review of Financial Studies, 1(3), 195–227.

Campbell, J. Y., & Shiller, R. J. (1988b). Stock prices, earnings and expected dividends. Journal of Finance, 43(3), 661–676.

Campbell, J. Y., Lo, A. W., & MacKinlay, C. (1997). The econometrics of financial markets. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Capozza, D. R., Hendershott, P. H., & Mack, C. (2004). An anatomy of price dynamics in illiquid markets: Analysis and evidence from local housing markets. Real Estate Economics, 32(1), 1–32.

Case, K. E., Quigley, J. M., & Shiller, R. J. (2005). Comparing wealth effects: The stock market versus the housing market. Advances in Macroeconomics, 5(1), 1–32.

Case, K. E., & Shiller, R. J. (2003). Is there a bubble in the housing market? An analysis. Paper prepared for the Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, September 4–5, 2003.

Chan, H. L., Lee, S. K., & Woo, K. Y. (2001). Detecting rational bubbles in the residential housing markets of Hong Kong. Economic Modelling, 18(1), 61–73.

Chen, C. R., & Sauer, D. A. (1997). Is stock market overvaluation persistent over time? Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 24(1), 51–66.

Claus, I., & Scobie, G. (2001). Household net wealth: An international comparison. Working paper 01/19, Wellington (New Zealand): New Zealand Treasury.

Cuthbertson, K. (1996). Quantitative financial economics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Dalziel, P., & Lattimore, R. (2001). The New Zealand macroeconomy: A briefing on the reforms and their legacy. Melbourne (Australia): Oxford University Press.

Daniel, K., Hirshleifer, D., & Subrahmanyam, A. (1998). Investor psychology and security market under-and-overreactions. Journal of Finance, 53(6), 2143–2184.

DeLong, J. B., Schleifer, A., Summers, L. H., & Waldmann, R. J. (1990). The economic consequences of noise traders. Journal of Political Economy, 98(4), 703–738.

Diba, B. T., & Grossman, H. L. (1988). Explosive rational bubbles in stock prices? American Economic Review, 78(3), 520–530.

Dissanaike, G. (1997). Do stock market investors overreact? Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 24(1), 27–50.

(The) Economist (2006a). Global house prices: Soft isn’t safe, March 4.

(The) Economist (2006b). Economic focus: News from the home front, June 10.

Englund, P., Hwang, M., & Quigley, J. M. (2002). Hedging housing risk. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 24(1/2), 167–200.

Farlow, A. (2004). UK house prices: A critical assessment. Part One of a report prepared for the Credit Suisse First Boston Housing Market Conference in May 2003, London: Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB), January, Available for download at http://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/members/andrew.farlow/Part1UKHousing.pdf.

Flavin, M., & Yamashita, T. (2002). Owner-occupied housing and the composition of the household portfolio. American Economic Review, 92(1), 345–362.

Froot, K. A., & Obstfeld, M. (1991). Intrinsic bubbles: The case of stock prices. The American Economic Review, 81(5), 1189–1214.

Goetzmann, W. N., & Ibbotson, R. G. (1990). The performance of real estate as an asset class. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 3(1), 65–76.

Hawksworth, J. (2004). Outlook for UK house prices - July 2004. In UK economic outlook (Chapter III, pp. 19–28), London: PricewaterhouseCoopers, Available for download at http://www.pwc.com/uk/eng/ins-sol/publ/ukoutlook/pwc_July04.pdf.

Helbling, T., & Terrones, M. (2003). When bubbles burst. In World economy outlook (Chapter II, pp. 61–94), Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, Available for download at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2003/01/pdf/chapter2.pdf.

Himmelberg, C., Mayer, C., & Sinai, T. (2005). Assessing high house prices: Bubbles, fundamentals, and misperceptions. Staff reports No. 218, New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Hong, H., & Stein, J. C. (1999). A unified theory of underreaction, momentum trading, and overreaction in asset markets. Journal of Finance, 54(6), 1839–1885.

Hort, K. (1998). The determinants of urban house price fluctuations in Sweden 1968–1994. Journal of Housing Economics, 7(2), 93–120.

Kyle, A. (1985). Continuous auctions and insider trading. Econometrica, 53(6), 1315–1335.

Lai, R. N., & Van Order, R. (2006). A regime shift model of the recent housing bubble in the United States. Working Paper, Aberdeen (Scotland): University of Aberdeen Business School.

Levin, E. J., & Wright, R. E. (1997). The impact of speculation on house prices in the United Kingdom. Economic Modelling, 14(4), 567–585.

Liang, Y., Chatrath, A., & McIntosh, W. (1996). Apartment REITs and apartment real estate. Journal of Real Estate Research, 11(3), 277–289.

Lui, W., Strong, N., & Xu, X. (1999). The profitability of momentum investing. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 26(9–10), 1043–1091.

Meen, G. (1996). Ten propositions in U.K. housing macroeconomics: An overview of the 1980s and early 1990s. Urban Studies, 33(3), 425–444.

Merton, R. (1973). An inter-temporal capital asset pricing model. Econometrica, 41(5), 867–888.

Merton, R. (1980). On estimating the expected return on the market: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Financial Economics, 8(4), 323–361.

New Zealand Official Yearbook 1984, 89th annual edition, Wellington (New Zealand): Department of Statistics.

Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor’s Speech (2006). Available for download at http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/speeches/2861623.pdf.

Roche, M. J. (2001). The rise in house prices in Dublin: Bubble, fad or just fundamentals. Economic Modelling, 18(2), 281–295.

Roehner, B. M. (1999). Spatial analysis of real estate price bubbles: Paris, 1984–1993. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 29(1), 73–88.

Shiller, R. (1984). Stock prices and social dynamics. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 457–498.

Sutton, G. D. (2002). Explaining changes in house prices. BIS Quartely Review, 46–55, October.

Thorp, C., & Ung, B. (2001). Recent trends in household financial assets and liabilities. Bulletin 64 (pp. 14–24). Wellington (New Zealand): Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

van den Noord, P. (2006). Are house prices nearing a peak? A probit analysis of 17 OECD countries. Working paper 488, Paris: OECD Economics Department, 1 June 2006.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Education Trust of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) and the Department of Finance and Quantitative Analysis, University of Otago is gratefully acknowledged. The authors would also like to thank two anonymous referees, Nic Groenewold (University of Western Australia) and the participants at seminars held at the University of Aberdeen, the University of Otago, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) for helpful comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the RBNZ. The responsibility for any remaining errors or ambiguities is the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The Fundamental Price-Income Model

The model described in the empirical framework section above has the following present value expression for the real value of household property, V t :

where V t is a constant proportion, γ, of the expected value of future real disposable income, Y t , discounted at the real discount rate, \( \rho ^{ * }_{t} \). Assuming the relationship between the real house price index P and market capitalization V, and the relationship between the value of all income, Y, and income covered by the house price index, are constant, then Eq. 8 is re-written as:

where P t = β′V t , and, defining β = β′(γ) and Q t = βY t .

We define the time stream of realized discount rates, ρ t , to satisfy:

Given the discussion of Eq. 9 above, Eq. 10 is a particular solution to \( P_{t} = {{\left( {P_{{t + 1}} + Q_{{t + 1}} } \right)}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\left( {P_{{t + 1}} + Q_{{t + 1}} } \right)}} {{\left( {1 + \rho _{{t + 1}} } \right)}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {{\left( {1 + \rho _{{t + 1}} } \right)}} \), and it follows that:

where P t is the real price at the end of period t, and Q t+1 is real disposable income measured during t + 1. Taking logs and using lower case letters to represent the logs of their upper-case counterparts, we can write:

where r is defined as ln(1 + ρ) and the term (q − p) can be viewed as the economy-wide income-price ratio. The first term in Eq. 12 can be linearized using a first-order Taylor’s approximation and Eq. 12 can be written as:

where k and μ are linearization constants:

where \( \overline{{{\left( {q - p} \right)}}} \) is the sample mean of (q − p) about which the linearization was taken. Clearly, 0 < μ < 1 and in practice is close to 1.

Empirically, it is common that both p and q are I(1) so that the variables are transformed to ensure stationarity. Denote by pq t the (log) price-income ratio, p t − q t , and rewrite Eq. 13 as:

After repeated substitution for \( pq_{{t + 1}} ,pq_{{t + 2}} , \ldots \) on the right-hand side of Eq. 14, we get:

Letting \( i \to \infty \) and assuming that the limit of the last term is 0, results in the following alternative form of Eq. 15:

Hence, if q t ∼ I(1) then Δq t ∼ I(0) and, assuming that r t ∼ I(0) (recall that it is the real discount rate), then pq t will be I(0) and we have the model linearized and expressed in terms of stationary variables. Finally, taking conditional expectations of both sides:

where \( E^{c}_{t} \) are conditional expectations and we interpret \( r_{{t + j + 1}} \) as investors’ required return.

In order to use Eq. 17 to generate a series for pq t *, the price-income ratio implied by the model and from it the implied or fundamental house price, p*, we need to obtain empirical counterparts to the terms on the right-hand side involving expectations. For the first of these, the expectation of disposable income growth, we incorporate disposable income growth into a three-variable VAR model (see below) while for the second we assume a time-varying risk premium, which we also include in the empirical VAR. Here we follow the work of Merton (1973, 1980) on the intertemporal CAPM, and model the time-varying risk premium as the product of the coefficient of relative risk aversion, α, and the expected variance of returns, \( E^{c}_{t} \sigma ^{2}_{t} \).Footnote 16 The equation for the price-income ratio then becomes:

where f is the constant real-risk free component of real required returns. In this case, we forecast both real income growth and the housing return variance using a three-variable VAR in \(z_{t} = {\left( {pq_{t} ,\Delta q_{t} ,\sigma ^{2}_{t} } \right)}\prime \). The empirical VAR is written in compact form as:

where A is a (3 × 3) matrix of coefficients and ɛ is a vector of error terms. We assume a lag length of 1 for ease of exposition. If, in the empirical application, a longer lag length is required, the companion form of the system can be used.

Forecasts of the variables of interest j + 1 periods ahead are achieved by multiplying z t by the jth + 1 power of the matrix A:

The equation from which we compute the fundamental price-income ratio (and hence the fundamental house price) is:

where \( {\mathbf{e}}^{\prime }_{2} {\mathbf{A}}^{{j + 1}} {\mathbf{z}}_{t} = E^{c}_{t} \Delta q_{{t + j + 1}} \) and \( {\mathbf{e}}^{\prime }_{3} {\mathbf{A}}^{{j + 1}} {\mathbf{z}}_{t} = E^{c}_{t} \sigma ^{2}_{{t + j + 1}} \) where \({\mathbf{e}}^{\prime }_{2} \) and \({\mathbf{e}}^{\prime }_{3} \) are, respectively, the second and third unit vectors. Hence the fundamental value of the price-income ratio is generated by a combination of the present value model and the forecasting assumptions.

Therefore pq t * provides a measure of the fundamental house price series once we have estimated the VAR coefficients and the constants μ, k, and f. Given that we wish to generate a series for real house prices that is warranted by (predicted) income growth, we generate (the log of) fundamental house prices as:

Equation 21 can also be used to derive tests of how far actual house prices deviate from their fundamental value as warranted by real disposable income. This is simply a test of \( pq_{t} = pq^{ * }_{t} \) for all t. Since \(pq_{t} = {\mathbf{e}}^{\prime }_{1} {\mathbf{z}}_{t} \) where \({\mathbf{e}}^{\prime }_{1} \) is the first unit vector, we can write Eq. 21, after transforming the variables to deviations from their means to remove the constant term, as:

This restriction is linear in the elements of A (denoted a) and in the present case simply amounts to:

and can be tested with a standard Wald test which is asymptotically χ 2-distributed with three degrees of freedom.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fraser, P., Hoesli, M. & McAlevey, L. House Prices and Bubbles in New Zealand. J Real Estate Finan Econ 37, 71–91 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9060-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9060-8