Abstract

Many of America’s top corporate donors share a common feature: the bulk of their giving is in the form of in-kind products, not cash. This phenomenon is not a coincidence but rather closely tied to the tax code creating such a preference due to an enhanced deduction for inventory donations. We examine a model of inventory choice under uncertainty and demonstrate that enhanced tax deductions not only promote giving, they also notably influence inventory planning and accelerate learning of customer demand. The results confirm that enhanced deductions can be used to promote pro-social behaviors such as boosting charitable giving, aligning inventories with consumer needs, and alleviating supply chain shortages. The results also demonstrate the potential risks of excessive tax preferences for inventory donations, including inflated retail prices and additional environmental waste.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that the present study presents a circumstance in which the preferred tax policy is time-invariant and manifests as a commonly observed institutional feature. Another mechanism that has such appealing features is the use of residual income as a performance measure to align investment priorities (e.g., Dutta and Reichelstein 2002). See Wilson (1987) and Glover (2012) for discussions on the importance of examining such mechanisms.

This prediction is consistent with recent empirical evidence showing that participation in food bank donation programs by grocery retailers is associated with higher food prices in the relevant product categories (Lowrey et al. 2023).

The expected consumer surplus per unit is readily confirmed from underlying consumer preferences. Intuitively, the consumers willing to purchase the product are those whose valuation exceeds \(p\). With consumer valuations evenly distributed, the average amount by which buying consumers valuations exceed this price is \(\left[1-p\right]/2\).

References

Anand, K., R. Anupindi, and Y. Bassok. 2008. Strategic inventories in vertical contracts. Management Science 54: 1792–1804.

Arikan, E. 2011. Single period inventory control and pricing: An empirical and analytical study of a generalized model. NED-New edition. Peter Lang AG, 2011, (Forschungsergebnisse der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien: Frankfurt), Vol. 43.

Arya, A., and B. Mittendorf. 2015. Supply chain consequences of subsidies for corporate social responsibility. Production and Operations Management 24: 1346–1357.

Aviv, Y., and A. Pazgal. 2008. Optimal pricing of seasonal products in the presence of forward-looking consumers. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 10: 339–359.

Baiman, S., S. Netessine, and R. Saouma. 2010. Informativeness, incentive compensation, and the choice of inventory buffer. The Accounting Review 85: 1839–1860.

Balakrishnan, K., J. Blouin, and W. Guay. 2019. Tax aggressiveness and corporate transparency. The Accounting Review 94: 45–69.

Barrett, W. 2022. Food bank network ousts United Way as America’s largest charity. Forbes, December 13. Accessed at https://www.forbes.com/sites/williampbarrett/2022/12/13/food-bank-network-ousts-united-way-as-americas-largest-charity.

Bisi, A., and M. Dada. 2007. Dynamic learning, pricing, and ordering by a censored newsvendor. Naval Research Logistics 54: 448–461.

Bo, H. 2001. Volatility of sales, expectation errors, and inventory investment: Firm level evidence. International Journal of Production Economics 72: 273–283.

Cachon, G. 2003. Supply chain coordination with contracts. In S. Graves and T. de Kok (eds.): Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science: Supply Chain Management (North Holland: Amsterdam), Vol. 11.

Cachon, G., and M. Lariviere. 2005. Supply chain coordination with revenue-sharing contracts: Strengths and limitations. Management Science 51: 30–44.

Cen, L., E. Maydew, L. Zhang, and L. Zuo. 2017. Customer-supplier relationships and corporate tax avoidance. Journal of Financial Economics 123: 377–394.

Chief Executives for Corporate Purpose. 2021. Giving in Numbers: 2021 Edition.

Chu, L., G. Li, and P. Rusmevichientong. 2018. Optimal pricing and inventory planning with charitable donations. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 20: 687–703.

Dutta, S., and S. Reichelstein. 2002. Controlling investment decisions: Depreciation- and capital charges. Review of Accounting Studies 7: 253–281.

Fessler, P. 2013. Thanks, but no thanks: when post-disaster donations overwhelm. NPR All Things Considered, January 9. Accessed at https://www.npr.org/2013/01/09/168946170/thanks-but-no-thanks-when-post-disaster-donations-overwhelm.

Gallemore, J., and E. Labro. 2015. The importance of the internal information environment for tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 60: 149–167.

Glover, J. 2012. Explicit and implicit incentives for multiple agents. Foundations and Trends in Accounting 7: 1–71.

Graham, J., M. Hanlon, T. Shevlin, and N. Shroff. 2017. Tax rates and corporate decision-making. The Review of Financial Studies 30: 3128–3175.

Hu, C., M. Hu, and Y. Xiao. 2021. Socially responsible newsvendor. Tsinghua University working paper. Accessed at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3805366.

Hwang, I., T. Jung, W. Lee, and D. Yang. 2021. Asymmetric inventory management and the direction of sales changes. Contemporary Accounting Research 38: 676–706.

Kline, D. 2017. This Wal-Mart number will surprise you. The Motley Fool, January 11. Accessed at https://www.fool.com/investing/2017/01/11/this-wal-mart-number-will-surprise-you.aspx.

Kocabiyikoglu, A., and I. Popescu. 2011. An elasticity approach to the newsvendor with price-sensitive demand. Operations Research 59: 301–312.

Kotsi, T., L. Van Wassenhove, and M. Hensen. 2014. Medicine donations: Matching demand with supply in broken supply chains. INSEAD working paper. Accessed at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2405956.

Lariviere, M., and E. Porteus. 1999. Stalking information: Bayesian inventory management with unobserved lost sales. Management Science 45: 346–363.

Loudenback, T. 2016. 25 of the most generous companies in America. Business Insider, June 23. Accessed at https://www.businessinsider.com/most-generous-companies-in-america-2015-2016-6.

Lovell, M. 1961. Manufacturers’ inventories, sales expectations, and the acceleration principle. Econometrica 29: 293–314.

Lowrey, J., T. Richards, and S. Hamilton. 2023. Food donations, retail operations, and retail pricing. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 25: 792–810.

McGuire, S., S. Rane, and C. Weaver. 2018. Internal information quality and tax-motivated income shifting. Journal of the American Taxation Association 40: 25–44.

Nagar, V., M. Rajan, and R. Saouma. 2009. The incentive value of inventory and cross-training in modern manufacturing. Journal of Accounting Research 47: 991–1025.

Petruzzi, N., and M. Dada. 1999. Pricing and the newsvendor problem: A review with extensions. Operations Research 47: 183–194.

Ross, J., and K. McGiverin-Bohan. 2011. The business case for product philanthropy. Indiana University working paper. Accessed at https://www.nchv.org/images/uploads/The_Business_Case_for_Product_Philanthropy_WEB.pdf.

Salazar, M. 2018. 6 restaurants that donate their food at the end of the day. Insider, August 3. Accessed at https://www.insider.com/restaurants-that-donate-food-at-the-end-of-the-day-2018-8.

Sherlock, M. 2022. Expired and expiring temporary tax provisions (including “tax extenders). Congressional Research Service, September 23.

Wang, Y., Z. Wang, B. Li, Z. Liu, X. Zhu, and Q. Wang. 2019. Closed-loop supply chain models with product recovery and donation. Journal of Cleaner Production 227: 861–876.

Wilson, R. 1987. Game-theoretic analysis of trading processes. In T. Bewley (ed.): Advances in economic theory (Fifth World Congress).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jennifer Blouin (editor), an anonymous referee, Ellen Aprill, Jeremy Bertomeu, Judson Caskey, Jim Celia, Kai Du, Brian Galle, Jon Glover, Phil Hackney, Steve Huddart, Minjo Kang, Eva Labro, Henock Louis, Michal Matejka, Richard Sansing, Tim Shields, Shyam Sunder, Joyce Tian, and workshop participants at the Korean Accounting Association Winter Conference, the Management Accounting Workshop Series, Pennsylvania State University, and Yonsei University for helpful comments. Anil Arya and Brian Mittendorf are grateful for the support of the John J. Gerlach Chair and H.P. Wolfe Chair in Accounting, respectively. Dae-Hee Yoon gratefully acknowledges support from the Yonsei University Research Fund of 2020 (Grant 2020-22-0038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Proposition 1

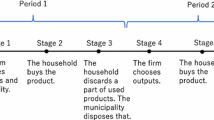

Using backward induction, we first solve for the firm’s period 2 stocking decisions. Given \(\psi\) and \({Q}_{1}\), in the event \({S}_{1}<{Q}_{1}\), \({D=S}_{1}\). In this case, the firm sets \({Q}_{2}^{l*}({Q}_{1};\psi ) =D\) since \(e<c\left[1-\tau \right]/\tau\) and \(p>c\) implies there is no reason to produce more or less than demand, respectively. When \({S}_{1}={Q}_{1}\), the firm learns only that \(D\ge {Q}_{1}\). In this case, the firm’s period 2 problem is in (1) and, using Leibniz’s rule, the first-order condition with respect to \({Q}_{2}^{h}({Q}_{1};\psi )\) is:

Solving the above first-order condition yields the following:

Using \({Q}_{2}^{l*}({Q}_{1};\psi )=D\), \({Q}_{2}^{h*}({Q}_{1};\psi )\) in (4), and noting \({Q}_{1}\) can be contingent on \(\psi\), the firm’s period 1 problem is in (2). Solving the first-order condition of this problem yields \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) in Proposition 1. Substituting this in (4) yields \({Q}_{2}^{h*}({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right);\psi )={Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)\), completing the proof of the proposition.

1.2 Proof of Proposition 2

-

(i)

The firm learns demand at the end of period 1 if and only if \(D<{Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\). Thus the ex ante probability of learning demand is \({\rho }^{*}={{E}_{\psi }[Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)/(\psi [1-p])]\). Substituting for \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) from Proposition 1 and noting that \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)/(\psi [1-p])\) is free of \(\psi\) yields the value of \({\rho }^{*}\).

-

(ii)

The firm’s expected charitable contributions in equilibrium, \({\Omega }^{*}\), equal:

Substituting \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) and \({Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)\) from Proposition 1 in (5) and replacing \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) by \({\rho }^{*}\psi [1-p]\) yields the expression for \({\Omega }^{*}\).

-

(iii)

The expected consumer surplus in equilibrium, \({\Phi }^{*}=[1-p]{E}_{\psi }[{S}_{1}+{S}_{2}]/2\), equals:

Substituting \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) and \({Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)\) from Proposition 1 in (6) and replacing \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) by \({\rho }^{*}\psi [1-p]\) yields the expression for \({\Phi }^{*}\).

-

(iv)

The firm’s expected production in equilibrium, \({\Lambda }^{*}\), equals:

Substituting \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) and \({Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)\) from Proposition 1 in (7) and replacing \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) by \({\rho }^{*}\psi [1-p]\) yields the expression for \({\Lambda }^{*}\).

1.3 Proof of Proposition 3

The following derivatives of the equilibrium quantities noted in Proposition 1 are convenient in establishing the comparative statics in Proposition 3.

Let \(e=\gamma Z\), where \(Z=Min\left\{c,[p-c]/2\right\}>0\).

-

(i)

Using \({{{\rho }^{*}=E}_{\psi }[Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)/(\psi [1-p])]\) and (8), it follows that:

-

(ii)

Using \({\Omega }^{*}\) from (5), it follows that:

The inventory levels in Proposition 1 are ordered as \(2{Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)>{Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)>{Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\). This, in conjunction with (8), implies \(\partial {\Omega }^{*}/\partial \gamma >0\).

-

(iii)

Using \({\Phi }^{*}\) from (6), it follows that:

With \(\psi \left[1-p\right]>{Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)>{Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) and (8), it follows that \(\partial {\Phi }^{*}/\partial \gamma >0\).

-

(iv)

Using \({\Lambda }^{*}\) from (7), it follows that:

With \(\psi \left[1-p\right]>{Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)>{Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) and (8), it follows that \(\partial {\Lambda }^{*}/\partial \gamma >0\).

1.4 Proof of Proposition 4

Define the firm’s expected profit expression in (3) by \(\Pi (p,e(p)).\) Consider \(e(p)=\gamma Min\{c,[{p}^{*}-c]/2\}=\gamma c\). Thus, at the optimal price \({p}^{*}\), the firm’s expected profit is \(\Pi ({p}^{*},\gamma c).\) Differentiating the first-order condition of the firm’s pricing problem, that is, \(\partial\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}=0\), with respect to \(\gamma\) yields \(d{p}^{*}/d\gamma =-({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}\partial \gamma )/({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*2}).\) At the interior maximum \({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*2}<0\), and hence the sign of \(d{p}^{*}/d\gamma\) is the same as the sign of \({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}\partial \gamma\). This cross partial is presented below:

where

Given \(\partial\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}=0\), tedious computations confirm \(A\le 0\). With the remaining term in the numerator and the denominator of \({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}\partial \gamma\) each positive, it follows that \({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}\partial \gamma \le 0\). Hence \(d{p}^{*}/d\gamma \le 0\) in the \(e=\gamma c\) case. Next consider \(e(p)=\gamma Min\{c,[{p}^{*}-c]/2\}=\gamma [{p}^{*}-c]/2\). In this case, the cross partial derivative is as below:

where

Given \(\partial\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}=0\), tedious computations confirm \(B\ge 0\). With the remaining term in the numerator and the denominator of \({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}\partial \gamma\) each positive, it follows that \({\partial }^{2}\Pi /\partial {p}^{*}\partial \gamma \ge 0\). Hence \(d{p}^{*}/d\gamma \ge 0\) in the \(e=\gamma [{p}^{*}-c]/2\) case.

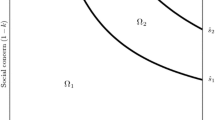

1.5 Proof of Proposition 5

The socially optimal period 2 stocking decisions are determined as follows. When \({S}_{1}<{Q}_{1}\), demand is known and \({Q}_{2}^{l\dagger}\left(\psi \right)=D\) since \(\kappa >\beta\) and \(p>\kappa\) implies there is no societal reason to produce more or less than demand, respectively. When \({S}_{1}={Q}_{1}\), the socially optimal \({Q}_{2}^{h\dagger}({Q}_{1};\psi )\) is obtained by solving:

The first order condition of (9) yields:

Stepping back, the socially optimal stocking level in period 1 solves:

The first-order condition of (11) yields \({Q}_{1}^{\dagger}\left(\psi \right)\). Substituting this in (10) yields \({Q}_{2}^{h\dagger}({Q}_{1}^{\dagger}\left(\psi \right);\psi )={Q}_{2}^{h\dagger}\left(\psi \right)\), completing the proof of part (i). Using the social planner’s preferred inventory levels in Proposition 5(i) and the firm’s preferred stocking choices in Proposition 1, part (ii) follows immediately since \({\left.{Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\right|}_{e={e}^{*}}={Q}_{1}^{\dagger}\left(\psi \right)\) and \({\left.{Q}_{2}^{h*}\left(\psi \right)\right|}_{e={e}^{*}}={Q}_{2}^{h\dagger}\left(\psi \right)\), where \({e}^{*}\) is free of \(\psi\). Finally, \({e}^{*}>0\) is equivalent to the condition \(\kappa <{\kappa }^{*}\), proving the tax preferences for donations.

1.6 Proof of Proposition 6

The firm’s profits in (1) and (2) are reduced by the additional amount of \(\left[1-\tau \right]\eta \left[{Q}_{t}-D\right]\) in the event \({Q}_{t}>D\), and an additional amount of \(\left[1-\tau \right]\lambda \left[D-{Q}_{t}\right]\) in the event \({Q}_{t}<D\). With this change, the firm’s optimal quantities are derived using precisely the same steps as in the proof of Proposition 1.

1.7 Proof of Proposition 7

The proof to determine the firm’s optimal (interior) stocking levels in the general distribution case using the first-order conditions follows the same steps as the proof of Proposition 1. In particular, the firm’s period 2 problem is as in (1) with \(1/[\psi (1-p)-{Q}_{1}]\) in the two integrands replaced by the general conditional distribution \(f\left(D;\psi ,p\right)/[1-F\left({Q}_{1};\psi ,p\right)]\); in addition, the upper limit of the integral is the upper bound of the general distribution. Again, \({Q}_{2}^{l*}({Q}_{1};\psi )=D\). Using Leibniz’s rule, the first-order condition for \({Q}_{2}^{h*}({Q}_{1};\psi )\) is:

From (12), it follows that \({Q}_{2}^{h*}({Q}_{1};\psi )\) satisfies:

The firm’s period 1 problem is in (2). With \({Q}_{2}^{l*}\left({Q}_{1}\left(\psi \right);\psi \right)=D\), the first-order condition of this problem with respect to \({Q}_{1}\left(\psi \right)\) yields:

Substituting for \(F\left({Q}_{2}^{h*}\left({Q}_{1}\left(\psi \right);\psi \right);\psi ,p\right)\) from (13) into (14) and solving for \({Q}_{2}^{h*}\left({Q}_{1}\left(\psi \right);\psi \right)\) yields:

From (13) and (15), it follows that \({Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\) satisfies:

(15), (16) with \({Q}_{1}\left(\psi \right)={Q}_{1}^{*}\left(\psi \right)\), and \({Q}_{2}^{l*}\left(\psi \right)=D\) correspond to the stocking levels.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Arya, A., Atanasov, T., Mittendorf, B. et al. Inventory planning and tax incentives for charitable giving. Rev Account Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-023-09818-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-023-09818-0