Abstract

This paper examines how analysts incorporate other comprehensive income (OCI) and its components into their earnings forecasts. We first document that analysts’ 1-year-ahead earnings forecasts are associated with OCI and OCI components having predictive ability; this suggests analysts (at least partially) incorporate this information into their forecasting. We then show that analysts are neither complete nor timely in incorporating OCI information into their forecasts, as several OCI components remain associated with analysts’ forecast errors. Further, we document that higher uncertainty in firm performance exacerbates analysts’ underreaction, evidencing a friction to full incorporation of OCI-related information. Finally, as evidence of where and when analysts derive OCI-related information, we document that analysts’ forecast revisions correlate with the release of firms’ 10-Ks and early 10-Qs (i.e., quarters one and two but not three).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Other comprehensive income (OCI) items are the performance elements reported outside of net income; comprehensive income (CI) is the net amount from adding net income and the OCI elements.

As further background, note that this debate is further complicated by the changing accounting policy for reporting CI/OCI. Initially, firms under US GAAP reported all elements of comprehensive income in a single statement of performance. Later, SFAS 130 (issued 1997) allowed the alternative treatment of reporting CI/OCI in the statement of changes in shareholders’ equity. The allowance of two reporting treatments appears to reflect the uncertain association between the OCI components and future cash flows. However, in 2011, the FASB issued Accounting Standards Update (ASU) No. 2011-05, “Reporting of Comprehensive Income,” Topic 220. Critically, this latter update requires that all CI/OCI elements be reported in the performance statements (i.e., income statement) by eliminating the option to report CI/OCI in the statement of changes in shareholders’ equity. This latter change appears consistent with the FASB viewing CI/OCI as performance-relevant information warranting inclusion in the income statement.

Using a sample of banks, Dong et al. (2014) find both OCI AFS and reclassified unrealized gains and losses of AFS securities predict one-year-ahead reclassification. Using the hand-collected reclassification data, we find similar evidence with our nonfinancial firm sample (results untabulated), confirming that part of the OCI AFS will be reclassified into NI in the subsequent period. Different from Dong et al. (2014), we focus on the current unrealized fair value changes of AFS securities (i.e., OCI AFS) rather than the realized components already included in NI. In addition, we use a sample of nonfinancial firms (rather than a sample of banks used by Dong et al. 2014), which generally have infrequent trading of AFS securities and therefore immaterial reclassification. We discuss this further in Section 6.3.

Specifically, when the AFS securities are equity securities, an increase in fair value represents a stock price increase for the investee companies, affecting future dividend revenues and operating cash flows. Similarly, when AFS securities are debt securities, the fair value changes in AFS securities reflect changes in the value of the underlying debt securities, including future interest and principal payments.

To demonstrate the potential effects of OCI AFS on firm’ future performance and financial condition, consider this example from our sample firm NVE Corporation’s 2015 annual report, which included an OCI unrealized loss ($295,088): “As of March 31, 2016, we held $85,392,719 in short-term and long-term marketable securities, representing approximately 85% of our total assets. A number of the securities we hold have been downgraded by Moody’s or Standard and Poor’s indicating a possible increase in default risk …We could incur losses on our marketable securities, which could have a material adverse impact on our financial condition, income, or cash flows, and our ability to pay dividends.”.

Most multinationals explain the impact of foreign exchange rate changes in their annual reports. For example, another sample firm (Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. 2015) reports the effects of negative foreign translation adjustments on current year’s revenue, cost of goods sold, and gross profit in its 2015 report: “gross profit decreased $0.7 billion, or 16%, to $4.0 billion due principally to lower ethanol margins ($0.6 billion) and foreign currency translation impacts ($0.2 billion).” Thus any continuing exchange rate trends would also affect 2016 foreign currency translation effects on revenue and gross profit can also continue.

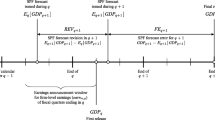

Choi and Zang (2006) examine the association between analysts’ EPS forecast revisions and errors with three OCI components (OCI AFS, OCI FC, and OCI PEN) using OCI data from 1998 to 2003. Of note, OCI data are incomplete during this period in the Compustat database, which strongly inhibits generalizability. In contrast, we begin our sample in 2004 when OCI data are widely available in Compustat. Further, Choi and Zang (2006) examine the association between OCI information and analysts’ revisions and forecast errors during the three months after the firms’ earnings announcements. However, most firms first disclose the OCI information in the annual reports rather than the earnings announcements. In contrast, we examine the revision from forecasts issued just after firms provide their annual reports to forecasts issued just before the earnings announcement.

The industry fixed effects represent two-digit SIC industry groupings. Results are unchanged to alternatively defining industry fixed effects using the 48 Fama–French industry groupings.

Effective for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2017, changes in the fair value of equity investments (except those accounted for under the equity method of accounting or those that result in consolidation of the investee) must be recognized in net income instead of other comprehensive income (FASB 2016). As a result, starting from fiscal 2018, the OCI AFS component only contains unrealized gains or losses on debt AFS securities (once the amendment becomes effective). This amendment reflects the FASB’s belief that fair value changes in AFS equity securities are performance-related measures, which should be included in earnings (FASB 2016). Of note, this view is consistent with our results that the OCI AFS component is informative for both evaluating the firm’s current economic performance and predicting its earnings and cash flows. Note that our results on the OCI AFS component may not hold for years after 2018 if the fair value changes on AFS debt securities are not associated with future earnings.

In particular, the unrealized cash flow hedge gains and losses are negatively associated with earnings after the hedge expires, because the fair value change reflects the price trend of the underlying hedge item. Note that this effect will not occur until after the firm reclassifies its current hedges into earnings. We replicate Campbell (2015) with our sample and confirm that accumulated fair value gains and losses on cash flow hedges (AOCI_HEDGE) are negatively associated with two-year-ahead changes in gross profit and changes in EPS (untabulated). In addition, Bratten et al. (2016) finds a negative association between OCI hedge and 1-year-ahead earnings in a sample of banks. The effect of the hedges on earnings depends on their expiration: if banks have hedges with shorter expirations, they are also more likely to have OCI HEDGE predictive of short-term earnings.

The lack of significant findings for the association between OCI_HEDGE and OCI_PEN with analysts’ forecasts and revisions is consistent with our results in Table 4, which suggests that neither of these two OCI components predicts one-year-ahead EPS.

Thus the regression estimations in Table 7 exclude firm-years having only one analyst forecast of one-year-ahead EPS, since dispersion is undefined for these observations. This leads to a smaller sample (N = 21,502 in Panel A; N = 20,604 in Panel B), relative to the other analyses.

In untabulated robustness analyses, we re-estimate Table 7 replacing the indicator variable HUnc by a percentile rank of average analysts forecast dispersion; results are unchanged.

We do not examine the remaining observations in our sample due to the cost of manually reading these documents. However, we assume that, if such discussion is consistently lacking in the latter observations where OCI is most material, then it is unlikely to be included in the less material observations.

Since many analysts do not provide forecasts between the earnings announcement and the issuance of the 10-K, the regression with Rev_10K has fewer observations than the other analyses reported in Table 8.

We require the last mean consensus forecast before the issuance of year t + 1’s 10-Q for each fiscal quarter to be reported after the quarterly fiscal end of each corresponding quarter.

These findings appear consistent with those of Gibbons et al. (2021), which documents that 26% of cases reflect analysts accessing EDGAR filings before making an EPS estimate change, with information acquisition via EDGAR associated with a significant reduction in analysts’ forecasting error, relative to their peers.

Within our sample, most last consensus forecasts before the issuance of year t + 1’s 10-Q (93%) are also reported before the quarterly earnings announcement. Thus Rev_10Q1, Rev_10Q2, and Rev_10Q3 may reflect analysts’ forecast revision based on both the latest earnings announcement and 10-Q. However, since earnings announcement do not appear to include OCI-related information, we believe that the quarterly OCI-related revisions are mainly driven by the 10-Q reporting.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this line of inquiry.

Note that 1,413 observations (33.7%) have OCI AFS equal to zero; this suggests that the lack of non-zero reclassifications for OCI AFS is not due to having zero OCI AFS values.

References

Amir, Eli, and Elizabeth A. Gordon. (1996). Firms’ choice of estimation parameters: Empirical Evidence from SFAS No. 106. Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance 11 (3): 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X9601100311.

Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. (2015). Annual report. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/7084/000000708416000046/adm-20151231x10k.htm. Accessed 21 Sept 2021.

Bamber, Linda S., John (Xuefeng) Jiang, Kathy R. Petroni, and Isabel Y. Wang. (2010). Comprehensive income: Who’s afraid of performance reporting? The Accounting Review 85(1): 97–126. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.1.97

Barker, Richard. (2004). Reporting financial performance. Accounting Horizons 18 (2): 157–172. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2004.18.2.157.

Biddle, Gary C., and Jong-Hag. Choi. (2006). Is comprehensive income useful? Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics 2 (1): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1815-5669(10)70015-1.

Bratten, Brian, Monika Causholli, and Urooj Khan. (2016). Usefulness of fair values for predicting banks’ future earnings: Evidence from other comprehensive income and its components. Review of Accounting Studies 21 (1): 280–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9346-7.

Brown, Lawrence, and Michael Rozeff. (1978). The superiority of analyst forecasts as measures of expectations: Evidence from earnings. Journal of Finance 33: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2326346.

Boulland, Romain, Gerald Lobo, and Luc Paugam. (2019). Do investors pay sufficient attention to banks’ unrealized gains and losses on available-for-sale securities? European Accounting Review 28 (5): 819–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2018.1562950.

Campbell, John L. (2015). The fair value of cash flow hedges, future profitability, and stock returns. Contemporary Accounting Research 32 (1): 243–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12069.

Campbell, John L., Jimmy F. Downes, and William C. Schwartz Jr. (2015). Do sophisticated investors use the information provided by the fair value of cash flow hedges? Review of Accounting Studies 20 (2): 934–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9318-y.

Chambers, Dennis, Thomas J. Linsmeier, Catherine Shakespeare, and Theodore Sougiannis. (2007). An evaluation of SFAS No. 130 comprehensive income disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies 12 (4): 557–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-007-9043-2.

Choi, Jong-Hag., and Yoonseok Zang. (2006). Implications of comprehensive income disclosure for future earning and analysts’ forecasts. Seoul Journal of Business 12 (2): 77–109.

Dhaliwal, Dan, K.R. Subramanyam, and Robert Trezevant. (1999). Is comprehensive income superior to net income as a measure of firm performance? Journal of Accounting and Economics 26 (1–3): 43–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(98)00033-0.

Dong, Minyue, Stephen Ryan, and Xiao-Jun. Zhang. (2014). Preserving amortized costs within a fair-value accounting framework: Reclassification of gains and losses on available-for-sale securities upon realization. Review of Accounting Studies 19 (1): 242–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9246-7.

Financial Accounting Standard Board. (1997). Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 130: Reporting Comprehensive Income. Norwalk, CT: FASB.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2016). Accounting Standards Update (ASU) No. 2016–01: Financial Instruments-Overall (Subtopic 825–10)—Recognition and Measurement of Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities.

Gibbons, Brian, Peter Iliev, and Jonathan Kalodimos. (2021). Analyst information acquisition via EDGAR. Management Science 67 (2): 661–1328. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3465.

Goncharov, Igor, and Allan Hodgson. (2011). Measuring and reporting income in Europe. Journal of International Accounting Research 10 (1): 27–59. https://doi.org/10.2308/jiar.2011.10.1.27.

Hayn, Carla. (1995). The information content of losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics 20 (2): 125–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(95)00397-2.

Hirst, D. Eric., and Patrick E. Hopkins. (1998). Comprehensive income reporting and analysts’ valuation judgments. Journal of Accounting Research 36: 47–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491306.

Hwang, Lee-Seok., Ching-Lih. Jan, and Sudipta Basu. (1996). Loss firms and analysts’ earnings forecast errors. The Journal of Financial Statement Analysis 1 (2): 18–30.

Jones, Denise A., and Kimberly J. Smith. (2011). Comparing the value relevance, predictive value, and persistence of other comprehensive income and special items. The Accounting Review 86 (6): 2047–2073. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10133.

Kanagaretnam, Kiridaran, Robert Mathieu, and Mohamed Shehata. (2009). Usefulness of comprehensive income reporting in Canada. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 28 (4): 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2009.06.004.

Kross, William, Byung Ro, and Douglas Schroeder. (1990). Earnings expectations: The analysts’ information advantage. The Accounting Review 65 (2): 461–476.

Krugman, Paul. (1989). Exchange rate instability. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Lang, Mark H., and Russell J. Lundholm. (1996). Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review 71 (4): 467–492.

Linsmeier, Thomas J., J. Gribble, R.G. Jennings, S. Mark Lang, K. Penman, D. Shores. Petroni, John H. Smith, and Terry D. Warfield. (1997). An issues paper on comprehensive income. Accounting Horizons 11 (2): 120–126.

Maines, Laureen A., and Linda S. McDaniel. (2000). Effects of comprehensive-income characteristics on nonprofessional investors’ judgments: The role of financial statement presentation format. The Accounting Review 75 (2): 179–207. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2000.75.2.179.

Mitra, Santanu, and Mahmud Hossain. (2009). Value-relevance of pension transition adjustments and other comprehensive income components in the adoption year of SFAS No. 158. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 33: 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-009-0112-4.

NVE Corporation. (2015). Annual report. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/724910/000072491015000010/NVE_2015_10K.htm. Accessed 21 Sept 2021.

O’Hanlon, John F., and Peter F. Pope. (1999). The value-relevance of UK Dirty Surplus accounting flows. The British Accounting Review 31 (4): 459–482. https://doi.org/10.1006/bare.1999.0116.

Richardson, Scott, Siew Hong Teo, and Peter D. Wysocki. (2004). The walk-down to beatable analyst forecasts: The role of equity issuance and insider trading incentives. Contemporary Accounting Research 21 (4): 885–924. https://doi.org/10.1506/KHNW-PJYL-ADUB-0RP6.

Pinto, Joann. (2001). Foreign currency translation adjustments as predictors of earning changes. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing & Taxation 10: 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1061-9518(01)00035-0.

Schweikart, James, and Robert Sanborn. (1991). Foreign currency translations may cause erratic equity positions. Journal of Applied Business Research 7 (4): 104–107. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v7i4.6211.

Skinner, Douglas. (1999). How well does net income measure firm performance? A discussion of two studies. Journal of Accounting and Economics 26 (1): 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(99)00005-1.

Zhang, X. Frank. (2006a). Information uncertainty and analyst forecast behavior. Contemporary Accounting Research 23 (2): 565–590. https://doi.org/10.1506/92CB-P8G9-2A31-PV0R.

Zhang, X. Frank. (2006b). Information uncertainty and stock returns. The Journal of Finance 61 (1): 105–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00831.x.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following for useful comments and discussion: Stephen Penman (editor), two anonymous reviewers, the faculty and doctoral students of Boston University, and conference participants at the 2018 Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance Conference and the 2018 AAA Western Region Meeting. We also thank Rachel Foss and Victoria Rice for their excellent research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, J., Cao, Y., Riedl, E.J. et al. Other comprehensive income, its components, and analysts’ forecasts. Rev Account Stud 28, 792–826 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09656-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09656-y