Abstract

We use the process through which insider trading (SEC Form 4) filings are made public to investigate whether media coverage affects the way securities markets assimilate news. To do this, we use recent changes in disclosure rules governing insider trades as well as the initiation of coverage by Dow Jones to cleanly identify media effects. Using high-resolution intraday data, we find clear effects of media dissemination on the way prices and volume respond to insider trading news in the minutes after its release. These results help to resolve open questions regarding the role of the media in capital markets, including why apparently second hand news affects securities prices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Lakonishok and Lee (2001) discuss the fact that CDA/Investnet’s Insider Trading Monitor, a vendor that specializes in insider information, often took several days to report the filing information. Studies of other types of SEC filings often had to make assumptions about when these filings became available to the public (Carter and Soo 1999; Alford et al. 1994).

Some firms voluntarily filed Form 4 documents electronically prior to the required June 2003 date. The SEC added the time-stamp to the actual filings in May 2002.

For example, Ng et al. (2008) show that transactions costs help explain post-earnings announcement drift by restricting the ability of informed traders to trade on earnings information and slowing its incorporation into price.

Our setting is less relevant for a different form of investor inattention, discussed by Hirshleifer et al. (2009), under which investors have limited cognitive ability and so get distracted by competing contemporaneous disclosures, such as a large number of earnings announcements on a particular day.

The PDS subscriber has two feeds; we take the first as the time the filing is available to the subscriber. As Rogers et al. (2015) discuss, there were around 40 PDS subscribers during our sample period, so it could be that other PDS subscribers get the data before the time we designate as the time of first public dissemination. To the extent this happens, our measure of the time of first public dissemination is biased late, which understates the gap between first public dissemination and dissemination by Dow Jones and adds noise to our tests, making it more difficult to detect market effects.

We have also run our main analyses, as reported in Fig. 3, separately for the two subsamples (that is, “PDS first” and “SEC first” observations). These results, available upon request, support the conclusions of the analyses that we report below.

Our tests assume that the clocks we use to measure the time of first public dissemination (which comes from our PDS data, described above) and by TAQ are correctly synchronized. Rogers et al. (2015) provide evidence that this is likely to be the case. The tests also assume that there is no delay in recording the quotes using TAQ, which is supported by Rogers (2008).

We take cumulative dollar volume from t = −60 through event second t minus the average volume for the exact same window (calculated over the previous 52 weeks), deflated by the average cumulative volume for the entire 120 s window (again calculated over the prior 52 weeks).

Note that the spread plot in Panel C begins 10 s before initial dissemination, while Panels A and B begin at initial dissemination. As the plots shows, spreads begin to move several seconds before initial dissemination, perhaps indicating that some market participants are aware of the forthcoming news.

These results differ from previous papers such as that by Bushee et al. (2010), who show that greater dissemination lowers spreads in daily data. Dissemination may initially increase spreads by exacerbating information asymmetries among market participants (Kim and Verrecchia 1994), but spreads may then recede as more market participants receive and assimilate the news. As discussed above, Rogers et al. (2015) show that, in some cases, the information in insider filings is available to certain market participants (PDS subscribers and their clients) before others, which likely increases information asymmetry.

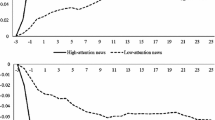

We also analyze whether these patterns differ for large and small trades. We find that the overall price effect is larger for larger trades and that prices respond more quickly for larger trades. Because trade size is larger for the long-delay group compared to the short-delay group (Table 3), this biases against the result we observe in Panel A of Fig. 3.

We exclude Thomson Reuters trades that have “cleanse indicator” codes of S (i.e., the security does not meet collection requirements) or A (i.e., excessive missing or invalid items).

It is clear from Fig. 5 that Dow Jones does not cover all filings. The difference is likely related to Dow Jones’ coverage incentives and so to firm size and market interest (Miller 2006). Solomon and Soltes (2012, p. 12) report that “… market capitalization and industry explain between 36 and 41 % of the variation in the number of newswire articles, and between 21 and 26 % of the variation in the number of newspaper articles.” This is not a problem for our analysis because our within-firm matching directly controls for any coverage effects.

References

Alford, A. W., Jones, J. J., & Zmijewski, M. E. (1994). Extensions and violations of the statutory SEC Form 10-K filing requirements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17, 229–254.

Bagnoli, M., Kross, W., & Watts, S. G. (2002). The information in management’s expected earnings report date: A day late, a penny short. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 1275–1296.

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2008). All that glitters: The effect of inattention and new on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Review of Financial Studies, 21, 785–818.

Blankespoor, E., Miller, G. S., & White, H. (2014). The role of dissemination in market liquidity: Evidence from firms’ use of Twitter. The Accounting Review, 89, 79–112.

Brochet, F. (2010). Information content of insider trades before and after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The Accounting Review, 85, 419–446.

Bushee, B. J., Core, J. E., Guay, W., & Hamm, S. J. W. (2010). The role of the business press as an information intermediary. Journal of Accounting Research, 48, 1–19.

Carter, M. E., & Soo, B. S. (1999). The relevance of Form 8-K reports. Journal of Accounting Research, 37, 119–132.

Cohen, L., Malloy, C., & Pomorski, L. (2012). Decoding inside information. The Journal of Finance, 67, 1009–1043.

D’Souza, J. M., Ramesh, K., & Shen, M. (2010). The interdependence between institutional ownership and information dissemination by data aggregators. The Accounting Review, 85, 159–193.

Dai, L., Parwada, J. T., & Zhang, B. (2015). The governance effect of the media’s news dissemination role: Evidence from insider trading. Journal of Accounting Research, 53, 331–366.

Davies, P. L., & Canes, M. (1978). Stock prices and the publication of second-hand information. The Journal of Business, 51, 43–56.

Dellavigna, S., & Pollet, J. M. (2009). Investor inattention and Friday earnings announcements. The Journal of Finance, 64, 709–749.

Doyle, J. T., & Magilke, M. J. (2009). The timing of earnings announcements: An examination of the strategic disclosure hypothesis. The Accounting Review, 84, 157–182.

Drake, M. S., Guest, N. M., & Twedt, B. J. (2014). The media and mispricing: The role of the business press in the pricing of accounting information. The Accounting Review, 89, 1673–1701.

Dyck, A., Volchkova, N., & Zingales, L. (2008). The corporate governance role of the media: Evidence from Russia. The Journal of Finance, 63, 1093–1135.

Easley, D., & O’Hara, M. (2004). Information and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 54, 1553–1583.

Engelberg, J. E., & Parsons, C. A. (2011). The causal impact of media in financial markets. The Journal of Finance, 66, 67–97.

Finnerty, J. E. (1976). Insiders and market efficiency. The Journal of Finance, 31, 1141–1148.

Hirshleifer, D., Lim, S. S., & Teoh, S. H. (2009). Driven to distraction: Extraneous events and underreaction to earnings news. The Journal of Finance, 64, 2289–2325.

Huberman, G., & Regev, T. (2001). Contagious speculation and a cure for cancer: A nonevent that made stock prices soar. The Journal of Finance, 56, 387–396.

Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1991). Market reaction to anticipated announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 30, 273–309.

Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1994). Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17, 41–67.

Lakonishok, J., & Lee, I. (2001). Are insider trades informative? The Review of Financial Studies, 14, 79–111.

Li, E. X., Ramesh, K., & Shen, M. (2011). The role of newswires in screening and disseminating value-relevant information in periodic SEC reports. The Accounting Review, 86, 669–701.

Lorie, J. H., & Niederhoffer, V. (1968). Predictive and statistical properties of insider trading. Journal of Law and Economics, 11, 35–53.

Miller, G. S. (2006). The press as a watchdog for accounting fraud. Journal of Accounting Research, 44, 1001–1033.

Miller, G. S., & Skinner, D. J. (2015). The evolving disclosure landscape: How changes in technology, the media, and capital markets are affecting disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, 53, 221–239.

Ng, J., Rusticus, T. O., & Verdi, R. S. (2008). Implications of transactions costs for the post-earnings announcement drift. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 661–696.

Niessner, M. (2015). Strategic disclosure timing and insider trading. Unpublished paper, Yale University, February 26. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2439040

Patell, J. M., & Wolfson, M. A. (1982). Good news, bad news, and the intraday timing of corporate disclosures. The Accounting Review, 57, 509–527.

Peress, J. (2014). The media and the diffusion of information in financial markets: Evidence from newspaper strikes. The Journal of Finance, 69, 2007–2043.

Rogers, J. L. (2008). Disclosure quality and management trading incentives. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 1265–1296.

Rogers, J. L., Skinner, D. J., & Zechman, S. L. C. (2015). Run EDGAR Run: SEC dissemination in a high frequency world. Unpublished paper, University of Chicago, January. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2513350

Seyhun, H. N. (1986). Insiders’ profits, cost of trading, and market efficiency. Journal of Financial Economics, 16, 189–212.

Solomon, D., & Soltes, E. (2012). Managerial control of business press coverage. Unpublished working paper, University of Southern California and Harvard Business School, October. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1918138

Tetlock, P. C. (2011). All the news that’s fit to reprint: Do investors react to stale information? The Review of Financial Studies, 24, 1481–1512.

Twedt, B. J. (2016). Spreading the word: Price discovery and newswire dissemination of management earnings guidance. The Accounting Review, 91, 317–346.

Verrecchia, R. E. (1981). On the relationship between volume reaction and consensus of investors: Implications for interpreting tests of information content. Journal of Accounting Research, 19, 271–283.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to an anonymous referee, Holly Yang (RAST conference discussant), and workshop participants at Colorado, Cornell, the HBS IMO Conference, Melbourne, Ohio State, Singapore Management University, Syracuse, UCLA, UC-San Diego, University of New South Wales, University of Queensland, and the RAST conference at LBS for comments on previous versions. This research was funded in part by the Accounting Research Center and the Fama-Miller Center for Research in Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

Independent variables (Tables)

Note: all continuous variables winsorized at 1 and 99 %.

- Trade size:

-

= The dollar value of the insider purchase, from Thomson Reuters

- Firm size:

-

= Total assets, from Compustat, in millions

- Filing cluster:

-

= The number of filings posted to EDGAR in the 60 s before the Form 4 posting

- Prior trading:

-

= The total amount of purchase activity, in dollars, that the insider engaged in during the prior 365 days, from Thomson Reuters

- CEO:

-

= 1 if the insider is the CEO, 0 otherwise

- CFO:

-

= 1 if the insider is the CFO, 0 otherwise

- Time trend:

-

= a measure of chronological time, equal to 1 for observations in the first month of the data and 22 for those in the last month

Market reaction variables (Figures)

- Returns:

-

= The percentage change in price where price is defined as the midpoint of the bid-ask spread, measured at time t, deflated by price at t=0, where t=0 is defined in specific tables/figures

- % Abnormal volume:

-

= Cumulative dollar volume from t = 0 to through event second t minus the average of the same for the exact same window (calculated over the prior 52 weeks), deflated by the average cumulative volume for the entire 120 s window (again calculated over the prior 52 weeks)

- % Abnormal spreads:

-

= The percentage abnormal spread, measured as (actual spread − normal spread for time t)/(normal spread at 60 s before dissemination)

Appendix 2: Example of a randomly chosen insider purchase filed on a Form 4 and covered by Dow Jones

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rogers, J.L., Skinner, D.J. & Zechman, S.L.C. The role of the media in disseminating insider-trading news. Rev Account Stud 21, 711–739 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-016-9354-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-016-9354-2