Abstract

We document that stocks with the strongest prior 12-month returns experience a significant average market-adjusted return of 1.58% during the five trading days before their earnings announcements and a significant average market-adjusted return of −1.86% in the five trading days afterward. These returns remain significant even after accounting for transactions costs. We empirically test a limited attention explanation for these anomalous returns—that stocks with sharp run-ups tend to attract individual investors’ attention and investment dollars, particularly before their earnings announcements. Our analysis suggests that the trading decisions of individual investors are at least partly responsible for the return pattern that we observe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper examines whether past stock market winners exhibit a predictable return pattern around their earnings announcements. Our analysis is motivated by the prior work of Trueman et al. (2003) who document an economically large abnormal return over the 5 days prior to internet stocks’ earnings releases during the 1998 through 2000 period and a sharp reversal over the subsequent 5 days. Trueman et al.’s (2003) sample period coincides with a time when internet stocks were rising rapidly. This invites the question of whether the documented return pattern is unique to internet stocks during a relatively short period, or whether it is a more general phenomenon, which manifests itself in stocks with strong prior returns.

Our analysis finds the phenomenon to be widespread. For the 35-year period beginning in 1971, the top percentile of stocks in terms of past 12-month price performance (sometimes referred to as the “past winners”) experience a significant average market-adjusted return of 1.58% during the 5 days prior to their earnings announcements (the “pre-announcement period”) and a significant average market-adjusted return of −1.86% in the 5 days after (the “post-announcement period”).Footnote 1 By way of contrast, the average pre-announcement market-adjusted return for our entire sample of stocks is a meager 0.30%, while the average post-announcement market-adjusted return is a negligible −0.1%.Footnote 2

There are two sources of noise in our estimates of pre- and post-announcement period returns. The first is uncertainty over the exact timing of some of the announcements in our sample, which leads to uncertainty over the beginning and ending dates of our pre- and post-announcement periods. The second is the presence of intraday earnings announcements, which make it impossible to precisely separate pre-announcement and post-announcement returns (unless intraday pricing data is available). To abstract from these sources of noise, we recalculate our pre- and post-announcement returns for just those earnings announcements whose dates can be verified through press releases and that occur outside of regular trading hours. The average pre-announcement period market-adjusted return for this subsample is 3.09%, which is almost double that of our top percentile as a whole.Footnote 3 The corresponding return for the post-announcement period, −3.05%, is more than 60% larger than that of our top percentile sample.Footnote 4

We examine whether limited attention—the notion that individual investors are more likely to buy stocks that draw their attention—is a possible explanation for this anomalous return pattern. Limited attention has been conjectured as an explanation for investors’ underreaction to earnings surprises (Hirshleifer et al. 2008; Hou et al. 2008), their underreaction to the information in pro-forma earnings announcements (Doyle et al. 2003), the price impact of Friday earnings releases (Dellavigna and Pollet 2009), observed investor over-optimism with respect to firms with high levels of net operating assets (Hirshleifer et al. 2004), and the abnormally high levels of individual investor share purchases around the time of earnings announcements (Lee 1992; Barber and Odean 2008).

The stocks that we focus on likely attract investors’ attention due to their sharp past returns. Their attention is likely to be further heightened just before the firms’ earnings announcements—another attention-grabbing event. Similar to Barber and Odean (2008), we test this possible explanation by calculating the abnormal order imbalance (as defined in Lee 1992) for small, medium-sized, and large traders around the time of our past winners’ earnings announcements. Since smaller investors are arguably the less sophisticated ones, they are more likely to be motivated to buy stocks with strong prior returns just before the earnings release. Consequently, we would expect to observe an unusually large number of buyer-initiated trades relative to seller-initiated trades in the pre-announcement period for these traders but not necessarily for larger ones. Once earnings are released and the focus shifts from these stocks, this positive abnormal order imbalance should disappear.

Our results are consistent with these conjectures. During the pre-announcement period small and medium-sized traders evidence a significantly positive abnormal order imbalance. In contrast, the imbalance is insignificant for large traders. In the post-announcement period, the positive abnormal order imbalances of the small and medium-sized traders disappear. This evidence suggests that limited attention on the part of smaller, naïve investors is at least partly responsible for the observed return pattern around the earnings announcements of past stock market winners. A number of supplementary tests that we perform all support this conclusion.

In contemporaneous work, Frazzini and Lamont (2007) also analyze the abnormal daily returns around firms’ earnings announcements, albeit unconditional on prior stock price movements. They document a 9-day pre-announcement period (ending 2 days before the announcement date) average abnormal return of 0.25% and an additional 0.30% positive return premium during the 10 days afterward (beginning 2 days after the announcement). Over the 3 days surrounding the earnings announcement, the average abnormal return is 0.21%. The authors also find a positive average abnormal order imbalance for the large traders before the earnings announcement, which turns negative just afterward. For the small traders, the average abnormal order imbalance hovers around zero during the entire period, except for the 3 days surrounding the earnings announcement, when it is sizable. The authors posit that the pre-announcement price increase stems from buying by large traders, who are anticipating an increase in the buying of small traders around the earnings announcement and an accompanying increase in prices.

Our findings provide a number of insights for future research. First, they reveal the importance of controlling for prior stock returns when measuring the price reaction to earnings announcements. Second, they suggest that long-term price momentum strategies can be improved upon by deliberately avoiding the sale of stock during the week after earnings announcements.Footnote 5 Third, they open up the possibility that previously documented short-term return reversal results might be partly explained by the phenomenon documented here. If so, then excluding earnings announcement periods from the analysis has the potential to significantly reduce the returns to short-term momentum strategies.Footnote 6

This paper proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2, we describe our sample selection process and present descriptive statistics. In Sect. 3, we analyze the earnings announcement returns of stocks displaying strong prior performance. Potential explanations for the anomalous return pattern that we observe are explored in Sect. 4. Section 5 ends the paper.

2 Sample selection and descriptive statistics

Our sample consists of all quarterly earnings announcements on Compustat issued between January 1, 1971 and September 30, 2005, by firms (a) that are listed on CRSP, (b) that have a December 31 fiscal year-end, and (c) whose stock price at the end of the previous quarter was at least $5. These requirements yield a sample of 293,630 firm-quarter observations.Footnote 7

For all the firms in our sample with earnings announcements in quarter t, we compute raw stock returns for the 12-month period ending on the last trading day of quarter t-1.Footnote 8 We rank the stocks in ascending order according to their returns, and partition the firms into deciles. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for each decile. As reported in panel A, average end-of-quarter market value increases monotonically from decile 1 ($775 million) to decile 8 ($2.267 billion). This is not surprising since firms in higher deciles have experienced greater percentage share price increases (and greater percentage increases in market value) than those in lower deciles. Average market values decrease as we move to deciles 9 ($1.941 billion) and 10 ($1.243 billion). This drop is consistent with extreme returns being more prevalent in less established firms, which tend to be smaller. The median end-of-quarter market values display a similar pattern. They increase monotonically from decile 1 ($130 million) to decile 7 ($333 million) and then decrease to $213 million for decile 10.

Panel B presents the average prior 12-month raw return for each decile; by construction, it is monotonically increasing across deciles. Not surprisingly, the average raw returns for the bottom and top deciles, containing the most extreme returns, are particularly large. The average raw return of −39.5% for the first decile is more than twice the size of that of the second decile, while the average raw return for the tenth decile, 153.5%, is two and a half times that of decile nine.

The average market-adjusted return during the pre-announcement period (the five trading days up to and including the earnings announcement date as recorded in Compustat) appears in panel C for each decile.Footnote 9 The corresponding returns for the post-announcement period (the five trading days after the earnings announcement date) are presented in panel D. There is an almost monotonic increase in pre-announcement average market-adjusted returns as we move from lower to higher deciles. Moreover, the average market-adjusted return for the top decile, 0.83%, is more than 50% greater than that of the ninth decile and is almost three times as large as the average pre-announcement market-adjusted return of 0.3% over our entire sample.

The negative average post-announcement market-adjusted return of the first decile, −0.29%, is suggestive of price momentum, with the negative prior 12-month returns continuing into the post-announcement period. In contrast, the negative average market-adjusted return of the top decile, −0.71%, reflects a sharp reversal of the returns generated both in the pre-announcement period and over the prior 12 months. It is more than seven times the size of the average post-announcement market-adjusted return of −0.1% for our sample as a whole.Footnote 10

3 The top percentile

3.1 Descriptive statistics

The results obtained thus far suggest the possibility that the return reversal pattern observed in the top decile is even sharper within the highest percentile. To investigate this possibility, we partition the top decile into ten percentiles according to prior 12-month return. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for each of these percentiles. As seen from panel A, average market values exhibit a mostly decreasing trend as we move from the 91st percentile ($1.872 billion) to the 100th percentile ($726 million). The same is true for median market values, which decrease from $256 million for the 91st percentile to $168 million for the top percentile. The prior 12-month return (panel B) varies over a wide range, from an average of 81.8% for the 91st percentile to 399.0% for the top percentile. That top percentile return is almost twice the size of the corresponding return for the 99th percentile and is more than twice the average return for the top decile overall.

Panels C and D report average pre-announcement and post-announcement market-adjusted returns for the top ten percentiles. These returns generally increase in magnitude as we move from the 91st to the 100th percentile. The average pre-announcement market-adjusted return for the top percentile, 1.36%, is over 60% higher than that of the top decile as a whole. The top percentile’s average post-announcement market-adjusted return of −1.75% is over twice the size of that for the top decile. Given their economically large pre- and post-announcement returns, we focus the remainder of our analysis on this top percentile of observations.Footnote 11

3.2 Refining the earnings announcement dates

There are two drawbacks to using the Compustat database to obtain earnings announcement dates. First, the dates provided are not always correct. Second, the times of the earnings releases aren’t provided. To understand why the latter is a problem, consider two firms that release earnings on the same day, one before normal trading hours begin and one after they end. For the firm announcing before the market opens, the post-announcement period actually begins with that trading day. For the firm announcing after the market closes, the post-announcement period begins on the next trading day.Footnote 12 Not knowing the time of the earnings release then leaves in doubt the exact end of the pre-announcement period and beginning of the post-announcement period.

To mitigate the impact that these ambiguities have on our analysis, we turn to the actual earnings press releases, when available, to obtain the precise dates and times of the earnings announcements within our top percentile. (The Factiva database is our source of press releases.) If the time of a press release is either before the market opens or during normal trading hours, the previous trading day is set as the last day of the pre-announcement period.Footnote 13 If the time of the press release is after regular trading hours, the just-ended trading day is the end of the pre-announcement period. If the press release has no time stamp, then we arbitrarily assume that the announcement is made after trading hours and take as the last trading day of the pre-announcement period the day of the release. To the extent that these announcements are actually made before or during trading hours, this assumption has the effect of artificially damping the positive pre-announcement period returns. This is because the actual first day of the post-announcement period (and its associated negative returns) will mistakenly be included within the pre-announcement period (and its positive returns). For an earnings announcement without an accompanying press release on Factiva, we end the pre-announcement period on the Compustat announcement date. For simplicity, and where it will not cause confusion, we sometimes refer to the last day of the pre-announcement period as the earnings announcement day.

A byproduct of our detailed examination of each observation in the top percentile is the identification of a number of observations that clearly have data errors. Dropping those observations leaves us with a final sample of 2,868 earnings announcements. Press releases with date and time stamps were found for 2,314, or 81%, of them. For 55% of those observations, the press release and Compustat announcement dates are identical; for 42% the Compustat date is between one and 5 days after that of the press release.

For our final sample, Table 3 presents the average daily and cumulative market-adjusted returns over the pre- and post-announcement periods.Footnote 14 Average daily pre-announcement returns are all positive and are significant for days −2 through 0 (where day 0 denotes the last day of the pre-announcement period). Average daily post-announcement returns are all negative and significant. Cumulative market-adjusted returns over the pre- and post-announcement periods average 1.58 and −1.86%, respectively; both are reliably different from zero.

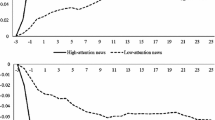

Figure 1 plots the year-by-year average pre- and post-announcement market-adjusted returns. Our results are generally consistent over time, with positive pre-announcement and negative post-announcement returns characterizing most of the individual years of our sample. Of the 35 years in our sample period, 28 have positive average market-adjusted pre-announcement returns, while 30 have negative average market-adjusted post-announcement returns. Given the high t-statistics for the pre- and post-announcement period returns reported in Table 3, the consistency over time is not surprising.

Average pre- and post-announcement market-adjusted returns, by year, for top percentile of observations ranked according to prior 12-month raw return, 1971–2005. For the firm-quarters in our sample, this figure depicts the average annual pre- and post-announcement market-adjusted returns, by year, for the top percentile of observations ranked according to prior 12-month raw return. Prior 12-month raw return is the raw stock return for the 12-month period ending on the last trading day of the just-ended quarter. The daily market-adjusted return equals the raw return minus the market return for that day. The market-adjusted return for the pre-announcement period equals the sum of the daily market-adjusted returns for the five trading days up to and including the earnings announcement date. The market-adjusted return for the post-announcement period equals the sum of the daily market-adjusted returns for the five trading days after the earnings announcement date

Our full-period returns are also consistent across firm size. We use the Fama and French (2008) definitions of small and large stocks to partition our sample.Footnote 15 In untabulated results, we find that small stocks exhibit a pre-announcement average market-adjusted return of 2.04%; the corresponding return for large stocks is 1.3%. For the post-announcement period, the average market-adjusted return is −2.30% for small stocks and −1.63% for large ones. All of these returns are reliably different from zero. That the results are stronger for smaller stocks is not surprising, as there are arguably fewer sophisticated investors following those firms.

Returning to the full-sample results, we can view them in a broader context by expanding the pre-announcement period to the 20 trading days prior to and including day 0 and the post-announcement period to the 20 trading days afterward. In order to ensure that the prior return accumulation period does not overlap with the pre-announcement period, we end the accumulation of returns (for this analysis only) 1 month before quarter end. The composition of the top percentile is then determined using this shortened return accumulation period. Table 4 presents the average daily market-adjusted returns from day −19 through day 20, as well as the cumulative average market-adjusted returns (CAR).Footnote 16 Figure 2 depicts the CAR graphically. For comparison, the corresponding CAR for our entire sample are also plotted. As the figure and table reveal, the CAR for the top percentile is almost monotonically increasing during the pre-announcement period, with the rate of increase growing in the few days before the earnings announcement. The mean of the average daily market-adjusted returns is 0.11% during the period from day −19 to day −5, jumping to an average of 0.35% during days −4 through 0. After the announcement, the CAR abruptly turns down, decreasing most rapidly during the first few post-announcement days and continuing downward, almost without interruption, through the 13th post-announcement day. For days 1 through 5, the mean of the average daily market-adjusted returns is −0.35%, decreasing in magnitude to −0.06% over days 6 through 13. At that point it resumes its upward trend, averaging 0.12% daily for days 14 through 20.

Cumulative average pre- and post-announcement market-adjusted returns for top percentile of observations ranked according to prior 11-month raw return. For the firm-quarters in our sample, this figure depicts the cumulative average market-adjusted return on each day from day −19 to day +20 around earnings announcements for all firms in our sample and for the top percentile of observations ranked according to prior 11-month raw return. Prior 11-month raw return is the raw stock return for the 11-month period ending 1 month before quarter end. The daily market-adjusted return equals the raw return minus the market return for that day. The cumulative market-adjusted return equals the sum of the market-adjusted returns from day −19 through the current day. Day 0 is the earnings announcement day

Taking the 40-day period as a whole, there is a clear upward trend in prices. Since it follows strong positive returns over the prior 11 months, it is likely to be a manifestation of price momentum. The 1.98% cumulative market-adjusted return that we observe over these 40 days would then translate into a momentum return of ~1% per month. Looking over a longer time period, untabulated results reveal an average raw return of 9.4 (15.1) percent over the six-month (12-month) period following the earnings announcements of our past winners. The corresponding returns found by Jegadeesh and Titman (1993) for their top decile of performers are 10.0 and 18.6%, respectively.

3.3 Additional analyses

3.3.1 Adjusting for same-day announcements

It is not uncommon for multiple earnings announcements to occur on the same date. The t-statistics reported in Tables 3 and 4, which assume independence across observations, are therefore likely to be overstated. To ensure that this is not affecting our conclusions, we repeat our analysis, replacing the daily pre- and post-announcement returns of firms announcing on the same date with a single observation whose daily return is equal to the average of those of the individual announcements. This reduces the number of observations used to calculate cumulative pre-announcement (post-announcement) period market-adjusted returns to 1,957 (1,955).

Table 5, panel A, presents the return results; they are qualitatively similar to those previously reported. The average market-adjusted return over the pre-announcement period is now a significant 1.50%; in the prior analysis, it was 1.58%. For the post-announcement period, the average market-adjusted return is a significant −1.77%; previously it was −1.86%. As before, average daily market-adjusted returns are significant for days −2 through 0 of the pre-announcement period and for all 5 days of the post-announcement period.

3.3.2 Alternative measures of risk

To ensure that our findings are not driven by the use of market-adjusted returns as a control for risk, we recompute abnormal returns using the four-factor model of Carhart (1997). We apply this model to calendar-time returns generated by following a two-pronged strategy of (a) purchasing the top percentile of stocks at the close of trading on day −5 and selling them at the close on day 0 and (b) selling the stocks short at the close on day 0 and covering the positions at the end of day 5. We construct long and short portfolios. As of the close of any day’s trading, the long portfolio is comprised of all stocks for which the current calendar date corresponds to an event day between −5 and −1. Analogously, the short portfolio is comprised of all stocks for which the calendar date corresponds to an event day between 0 and 4.

Assuming an initial investment of one dollar in each stock, the return on each portfolio on calendar date d, R d , is given by

where R id is the date d return on stock i in the portfolio; n d is the number of stocks in the portfolio as of the close of date d-1; and x id is the compounded daily return of stock i from the close of trading on the day it enters the portfolio through day d-1. (The variable x id equals 1 for a stock entering on day d-1.)

The portfolio’s average daily abnormal return is given by the intercept, α, from the following daily time-series regression:Footnote 17

where Rfd is the date d risk-free rate; Rmd is the date d return on the value-weighted market index; SMB d is the date d return on a value-weighted portfolio of small-cap stocks minus the date d return on a value-weighted portfolio of large-cap stocks; HML d is the date d return on a value-weighted portfolio of high book-to-market stocks minus the date d return on a value-weighted portfolio of low book-to-market stocks; and WML d is the date d return on a value-weighted portfolio of stocks with high recent returns minus the date d return on a value-weighted portfolio of stocks with low recent returns.Footnote 18 The regression yields parameter estimates of α, β, s, h, and w. The error term in the regression is denoted by ε d .

As reported in panel B of Table 5, the average daily abnormal return for the pre-announcement portfolio is a significant 33 basis points. For the post-announcement portfolio, it is a significant −28 basis points.Footnote 19 Multiplying by five to put these numbers on a comparable footing with the 5-day pre- and post-announcement returns previously calculated yields average abnormal returns of 1.65 and −1.40%, respectively. These are of the same order of magnitude as our event-time market-adjusted returns.

3.3.3 Predicting the earnings announcement date

The extent to which investors can capture the pre-announcement period abnormal returns calculated in the previous subsection depends on the precision with which they can forecast firms’ earnings announcement dates. Empirical evidence by Bagnoli et al. (2002) suggests that, at least in recent years, many firms have made it easier for investors to do so by disclosing their anticipated announcement dates. Using a database provided by First Call, the authors find that, over the 1995 through mid-1998 period, almost 26,000 quarterly earnings releases by over 4,400 firms were preceded by the announcement of the anticipated reporting date. The authors further note that the announcing firms in 1995 represent 53% of all firms on that year’s First Call analyst consensus forecast database and that the proportion increases to 68% by 1998. Moreover, in comparing the anticipated and actual earnings release dates, Bagnoli et al. (2002) find them to be identical for ~74% of their sample. The proportion increases from just under 60% in 1995 to more than 80% in 1998.

These findings, while suggestive of investors being able to exploit the pre-announcement period market-adjusted returns during the latter part of our sample period, are clearly not definitive. Moreover, investors’ ability to do so was undoubtedly much less in earlier years, before the internet brought about an explosion of publicly available financial data.

To estimate the pre-announcement market-adjusted returns that investors could have captured if no firm disclosed its anticipated release date, we first forecast release dates using the timing of past announcements. Specifically, for each observation in the top percentile we take the announcement date for the same quarter of the prior year as our estimate of the current quarter’s release date. If the prior year’s release date is unavailable on Compustat, we use the date of the prior quarter’s announcement, advanced by 3 months. In either case, if the predicted date falls on a weekend or holiday, we take the next trading day to be the forecasted release date. Figure 3 presents the distribution of the number of days difference between actual and forecasted announcement dates. The difference lies between −2 and +2 for almost 38% of the sample. For over 55% of the sample, the difference is between −5 and +5 days.

Histogram of the difference (in days) between the actual and predicted earnings announcement dates. This figure depicts the distribution of the number of days between the actual and predicted earnings announcement dates for the observations in the top percentile. For each observation the predicted announcement date is equal to the actual announcement date for the same quarter of the prior year. If the prior year’s release date is unavailable on Compustat, the date of the prior quarter’s announcement, advanced by 3 months, is used. If the predicted date falls on a weekend or holiday, the next trading day is taken to be the forecasted release date

We then recompute pre-announcement returns, given a strategy of purchasing each of the stocks in the top percentile at the close of trading 5 days before the anticipated announcement date and selling it at the actual earnings announcement date. This strategy clearly places a lower bound on the exploitable pre-announcement returns since it does not allow for the possibility that some firms disclose their anticipated announcement dates.

In untabulated results, we find the average daily market-adjusted return for the pre-announcement period under this revised strategy to be a significant 0.26%. This is equivalent to a 5-day average pre-announcement period abnormal return of 1.30%. While lower than the corresponding return of 1.58% that could be earned with foreknowledge of the actual earnings announcement dates, it remains of the same order of magnitude.

3.3.4 Earnings announcements outside normal trading hours

In this subsection we compute pre- and post-announcement returns for the subsample of earnings announcements that were made either before or after normal trading hours. By excluding those announcements made during the trading day, we eliminate the noise that arises from days that are mixtures of pre- and post-announcement trading. By dropping observations for which we do not have an exact announcement time, we eliminate any uncertainty over which days constitute the pre- and post-announcement periods. This ensures that the returns of one period are not inadvertently included in the returns of the other. Of the 2,868 announcements in our sample, 1,462 are known to have been made outside normal trading hours.

Table 5, panel C, presents average daily and cumulative pre-announcement and post-announcement market-adjusted returns for this subsample. With the pre-announcement period no longer contaminated by returns from the post-announcement period, the average market-adjusted return for the 5 days prior to the earnings announcement increases from 1.58 to 2.25%. Not surprisingly, much of that increase comes on day 0, when the market-adjusted return averages 0.91%, as compared with 0.59% for our entire sample. For the post-announcement period, the average market-adjusted return decreases from −1.86 to −2.2%.

We gain further insights by partitioning the day 1 (close-to-close) return into its overnight (close-to-open) and daytime (open-to-close) components. The impetus for doing so stems from Trueman et al. (2003), who find that positive pre-announcement period returns continue through the overnight period of day 1 but turn negative for the remainder of the day. The Trade and Quotation (TAQ) database compiled by the National Association of Securities Dealers is our source for opening stock prices. This database contains the prices and trading sizes of intraday stock trades, as well as intraday bid-ask quotes. Since TAQ begins in 1993, this analysis is restricted to the 1993 through 2005 time period. Of the 1,462 after-hours announcements in our subsample, 795 have opening prices on TAQ.

As reported in panel D of Table 5, there is a significantly positive day 1 close-to-open average return of 0.93% associated with these observations, which is more than offset by a significantly negative open-to-close average return of −1.21%.Footnote 20 Extending the accumulation of pre-announcement period returns through the open on day 1 therefore increases the average market-adjusted return for this period to 3.09%. Commencing the post-announcement period at the open on day 1, rather than at the close on day 0, increases the magnitude of the average market-adjusted return for that period to −3.05%. Purchasing our subset of stocks 5 days before their earnings announcements, closing the positions at the open on day 1, and then initiating short positions that are closed at the end of day 5 would generate an average market-adjusted return over the 10-day period of more than 6%.

3.3.5 Accounting for transactions costs

We demonstrate in this subsection that our results are robust to the inclusion of transactions costs, stemming principally from the bid-ask spread and brokerage commissions. To assess the bid-ask spread’s impact on pre- and post-announcement period returns, we recompute those returns under the assumption that all share purchases are executed at the prevailing ask price and all share sales occur at the prevailing bid price.Footnote 21 More precisely, in calculating pre-announcement returns for our full sample, we assume shares are purchased at the closing ask price on day −5 and sold at the closing bid price on day 0. In computing post-announcement returns, we assume that shares are shorted at the day 0 closing bid price and replaced at the closing ask price on day 5. For the subsample of announcements made outside normal trading hours, the pre-announcement position is assumed to be closed at the opening bid price on day 1; the post-announcement short position is established at that price as well.

The TAQ database is our source for opening and closing bid and ask prices. We take as each day’s opening bid-ask quote the first one reported on TAQ with a time stamp of 9:30 a.m. Eastern time or later. The day’s closing bid-ask quote is the last one reported on TAQ with a time stamp of no later than 4:00 p.m. Eastern time. Our analysis covers the years 1993 through 2005, the period over which the TAQ data is available.

An examination of the data reveals a number of instances where there are large differences between a day’s closing (opening) bid or ask and the day’s closing (opening) stock price. These deviations likely arise from an erroneous time stamp on an after-hours or before-hours quote, which makes the quote appear to have been in effect during normal trading hours. To ensure that these errors do not affect our results, we drop from our full-sample pre-announcement return calculations any observation for which either (1) the day −5 closing ask is greater than 150% of that day’s closing stock price or (2) the day 0 closing bid is less than 50% of that day’s closing stock price. For the post-announcement period return calculations, we drop any observation for which either (1) the day 0 closing bid is less than 50% of that day’s closing stock price or (2) the day 5 closing ask is greater than 150% of that day’s closing stock price. Similar criteria are applied to eliminate outliers from our subsample of announcements made outside of normal trading hours. As a result of applying these criteria, 49 (45) observations are dropped from our full-sample pre-announcement (post-announcement) period calculations; 51 observations are removed from our after-hours subsample in both the pre- and post-announcement periods.

As presented in Table 5, panel E, cumulative average market-adjusted returns remain significantly different from zero even after accounting for the impact of the bid-ask spread. For our sample as a whole, the 5-day pre-announcement period market-adjusted return averages 0.94; for the 5-day post-announcement period it averages −0.85%. For the subsample of announcements made outside of normal trading hours, market-adjusted returns average 1.66% for the 5-day pre-announcement period and −1.34% post-announcement.Footnote 22

The imposition of brokerage commissions lowers these market-adjusted returns. Our full-sample cumulative average pre- and post-announcement period market-adjusted returns will both remain significant, though, as long as round-trip commissions do not exceed 0.12% of transaction value.Footnote 23 Assuming a commission of $10 for each 1,000 shares traded (in line with the commissions charged by discount brokers during the period of our analysis), the round-trip cost of a 1,000 share trade will be less than 0.12% as long as the price of the shares traded exceeds $18.20. The average end-of-quarter share price (untabulated) for the firms in our sample is greater than $33; consequently, the pre- and post-announcement average market-adjusted returns will retain their significance in the presence of both the bid-ask spread and brokerage commissions. For the subsample of announcements made outside normal trading hours, average market-adjusted returns will remain significant as long as round-trip commissions do not exceed 0.52% of transactions value.Footnote 24 They fall below 0.52% as long as the traded share price exceeds $4. Since all of the stocks in our sample have share prices greater than $5, the average market-adjusted returns for our after-hours subsample will remain reliably different from zero after the imposition of both the bid-ask spread and brokerage commissions.

4 Limited attention as an explanation for the return pattern around earnings announcements

In this section we explore the possibility that the anomalous return pattern we document is due, at least in part, to limited attention on the part of small investors. These investors, faced with limited time and resources, are more likely to invest in stocks that draw their attention. Among such stocks are arguably those that have increased sharply in price.Footnote 25 Attention is likely to be heightened just before their earnings releases—another attention-grabbing event. Reflective of the presence of small investors in these firms, untabulated results reveal that the average end-of-quarter percentage of shares owned by non-institutional investors is highest (at 70.4%) for our past winners. The average over all the other percentiles is 63.1%. Also, average end-of-quarter analyst following (at 3.1 analysts), another sign of institutional interest, is lowest for this percentile. The average over the remaining percentiles is 4.2 analysts.

Price pressure from these investors might partially explain the positive pre-announcement returns, while a lessening of that pressure after the earnings announcements could, in part, explain the post-announcement return reversal. This would be manifested in an abnormally large number of buyer-initiated relative to seller-initiated trades (that is, a positive abnormal order imbalance) for smaller investors during the pre-announcement period (but not necessarily for larger traders). Once the earnings are released, the smaller investors’ positive abnormal order imbalance would disappear.Footnote 26 Whether the imbalance would turn negative for any size trader after the earnings announcement is unclear ex-ante, as it would depend on the extent to which the reported earnings justifies the pre-announcement stock price.

We employ the Lee and Ready (1991) algorithm to determine whether a trade is buyer-initiated or seller-initiated. A trade is considered to be buyer-initiated (seller-initiated) if it occurs (a) at the asking price (bid price) of the prevailing quote, (b) within the prevailing quote but closer to the ask than the bid (closer to the bid than the ask), or (c) at the midpoint of the quote and the last price change was positive (negative).Footnote 27 The TAQ database is our source for intraday prices, quotes, and trading sizes. We include only those trades made during the normal trading hours of 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Eastern Time. Lee and Ready (1991) find that quotes are sometimes incorrectly recorded in time ahead of trades and show that trade direction misclassifications can be reduced by comparing the trade price with the quote in effect 5 seconds earlier. We employ that refinement in our analysis.

We partition the trades reported on TAQ into three subgroups: (1) those with a value of $50,000 or less, which we associate with small traders, (2) those with a value between $50,000 and $100,000, which we assume are generated by medium-sized traders, and (3) those with a value of $100,000 or greater, which we assume come from large traders. In our analyses we include only those announcements for which there are small, medium-sized, and large trades on at least 1 day of the pre-announcement period as well as on at least 1 day of the post-announcement period.Footnote 28

Following Lee (1992), the order imbalance for trades of size s, s = small, medium-sized, and large, on event day t ∈ [−4, 5] for earnings announcement n, \( {\text{OI}}_{tn}^{s} , \) is defined as follows:

where \( {\text{NBUY}}_{tn}^{s} \;({\text{NSELL}}_{tn}^{s} ) \) denotes the number of buyer-initiated (seller-initiated) trades of size s during event day t for observation n. The difference between \( {\text{NBUY}}_{tn}^{s} \) and \( {\text{NSELL}}_{tn}^{s} \) is normalized by the total number of trades of size s during that day, \( {\text{NTRD}}_{tn}^{s} . \)

Analogous to the daily order imbalance, we define the order imbalance over days t = a to t = b for announcement n, \( {\text{OI}}_{n}^{a,\;b} , \) as follows:

where the size superscript, s, is suppressed for notational simplicity. The abnormal order imbalance for the 5-day pre-announcement period, denoted by \( {\text{AOI}}_{n}^{\text{pre}} , \) is then given by

where the “normal” 5-day order imbalance is estimated by averaging the order imbalances of the 12 five-day periods beginning 30 days after the earnings announcement and ending 89 days after.Footnote 29 Similarly, the abnormal order imbalance for the 5-day post-announcement period, denoted by \( {\text{AOI}}_{n}^{\text{post}} , \) is given by

The average abnormal order imbalance for each trader size during the pre- and post-announcement periods is presented in Table 6, panel A. The numbers are consistent with limited attention partially explaining the documented anomalous return pattern around earnings announcements. Small and medium-sized traders, those more likely to exhibit limited attention, have significantly positive average abnormal order imbalances during the pre-announcement period (columns (1) and (2)).Footnote 30 In contrast, the average abnormal order imbalance for large traders (column 3), those more likely to be sophisticated, is not reliably different from zero. Once the announcement is made and the attention paid to these stocks ebbs, the significantly positive average order imbalance evidenced by the small and medium-sized traders disappears.Footnote 31 They become (marginally) significantly negative. The average abnormal order imbalance for the large traders is also reliably less than zero over the post-announcement period.Footnote 32

Two supplementary tests support the notion of limited attention as a driver of the return pattern around past winners’ earnings announcements. In the first test, we regress pre-announcement market-adjusted returns on the abnormal order imbalances of the small, medium-sized, and large traders (as calculated above). If limited attention is at least partially responsible for our results, then the abnormal order imbalance of the small traders should be positively related to the magnitude of these returns. As seen in panel B of Table 6, the coefficient on the small trader abnormal order imbalance is, indeed, positive and significant. In contrast, the coefficients on the medium-sized and large trader abnormal order imbalances are not reliably different from zero.

In the second test, we subdivide our sample period into two subperiods, 1971 through 1989 and 1990 through 2005, and calculate average pre-announcement market-adjusted returns for each. During the first subperiod it was arguably more difficult for small investors to access a wide array of media sources and more expensive for them to act on their information (before the widespread use of the internet for information gathering and trading) than during the second subperiod. Consequently, we conjecture that, if limited attention plays a role in generating the anomalous return pattern that we document, then the average pre-announcement market-adjusted return will be smaller during 1971 through 1989 than during 1990 through 2005. Our results are consistent with this conjecture. As reported in Table 6, panel C, the average pre-announcement market-adjusted return during the second subperiod is 1.69%, which is significantly greater than the corresponding return of 0.74% during the first subperiod.Footnote 33

5 Summary and conclusions

In this paper we find a predictable pattern to the returns of past stock market winners around the times of their earnings announcements. For the 1971 through 2005 period, the top percentile of stocks ranked by prior 12-month price performance experience an economically large and significant average market-adjusted return of 1.58% during the five trading days before their earnings announcements and a corresponding return of −1.86% in the 5 days after. The average pre- and post-announcement market-adjusted returns for the subset of stocks that announced earnings outside of normal trading hours are 3.09 and −3.05%, respectively. These returns remain significant even after accounting for transactions costs.

We empirically test whether limited attention can, at least in part, explain these anomalous return patterns. Limited attention would suggest that stocks with strong prior returns capture the attention of smaller investors, especially just before their earnings releases, and that the resulting heightened demand for shares pushes up their prices. A lessening of that demand after the earnings announcements leads to a reversal of returns. Our results support this explanation. In particular, we find that during pre-announcement periods small and medium-sized traders evidence a significantly positive abnormal order imbalance, but large traders do not. After the earnings announcements, the small and medium-sized traders’ positive abnormal order imbalances disappear.

This study’s findings are reminiscent of the adage “buy on the rumor, sell on the fact.” There is a difference here, though, in that the “rumor” is simply that there is an upcoming earnings announcement, not that the news will necessarily be better than expected. In this sense, our results are similar to those of Bradley et al. (2003). They find that stocks recently taken public rise in price in advance of the ending of the quiet period, with the “rumor” being only that the lead banker’s analyst will shortly be issuing a research report, not that the content of the report will be any more positive than expected.

Notes

In untabulated results, we find that only 30% of the past winners are high-tech stocks.

These returns are similar in magnitude to those documented by Ball and Kothari (1991) and Berkman and Truong (2009). They find small average pre-announcement abnormal returns of 0.17 and 0.34%, respectively, and a negligible average abnormal return of −0.01% post-announcement. While not reporting abnormal returns, Chari et al. (1988) find an average pre-announcement raw return of 0.29% and an average post-announcement raw return of 0.26%.

Like Trueman et al. (2003) we define the pre-announcement period for this subsample as extending through the market open after the earnings release.

Our return pattern is distinct from that of the well-documented post-announcement drift (see, for example, Bernard and Thomas (1989) and Foster et al. (1984)). That phenomenon is evidenced by the continuation of post-announcement returns over a relatively long period of time, rather than a reversal of abnormally high pre-announcement returns in the immediate post-announcement period. On an annualized basis, the returns we document are much larger than those generated by the post-announcement drift.

Jegadeesh and Titman (1993), among others, show that a strategy of buying stocks that have performed well in the recent past and selling those that have performed poorly generates significant positive returns over 3- to 12-month holding periods.

Lehmann (1990) conditions on prior 1-week performance and finds that the best (worst) performing stocks underperform (outperform) the next week. Our work is different from his in that we are not conditioning on prior-week winners and are not focusing on whether return reversals exist around earnings announcements. Rather, we are analyzing the returns of past 52-week winners, both before and after their earnings announcements. We find strong positive market-adjusted returns in the pre-announcement period and sharp negative market-adjusted returns post-announcement. Note that given the differing natures of our analyses, it would be impossible to predict from his results that this pattern would exist. That the returns we document are much higher than his is further evidence of the differences between the two analyses. See also Jegadeesh (1990) and Gutierrez and Kelley (2008) for an analysis of short-term price reversals.

We have excluded from our sample those announcements with Compustat issue dates more than 90 days after quarter end since those dates are almost certainly in error. We repeated our primary return analysis with these observations included; the results are similar to those reported here.

For a firm whose earnings announcement date falls within the first five trading days of quarter t, the prior 12-month return accumulation period ends the day before the pre-announcement period begins. This ensures that there is no overlap between the two periods.

For the market return we take the value weighted return, including dividends, of all NYSE/AMEX/NASDAQ firms.

As a robustness check, we rank stocks based on prior 3-month, 6-month, and 9-month returns. Untabulated results are both qualitatively and quantitatively similar to those reported here.

We repeat this analysis, broadening our sample to include firms with fiscal year-ends at the end of March, June, September, or December. This results in an increase in sample size of 890 observations (from 2,868 to 3,758). Untabulated results reveal a significant 1.49% (−1.84%) average pre-announcement (post-announcement) market-adjusted return.

With after-hours trading more prevalent in recent years, the market response to these earnings releases often begins after regular trading hours on the earnings announcement day.

If there are several press releases pertaining to the same earnings announcement in Factiva, we take the disclosure time to be that of the earliest release.

In calculating the cumulative market-adjusted return for the pre-announcement period, we drop observations with one or more missing daily returns. We do the same for the post-announcement period. This leaves us with 2,866 observations pre-announcement and 2,864 post-announcement.

Fama and French (2008) define small stocks as those with market capitalizations between the 20th and 50th percentiles of all NYSE stocks and large stocks as those with market capitalizations above the 50th percentile. They characterize those stocks with market capitalizations below the 20th percentile as microcaps. We do not separately report pre- and post-announcement returns for the microcaps since there are only 54 of them in our top percentile sample.

Since the composition of the top percentile of stocks changes when the shorter prior return period is used, the average daily market-adjusted returns for days −4 through 5 differ somewhat from those reported in Table 3.

Dates on which the portfolio is empty are not included when estimating the regression.

We thank Ken French and James Davis for providing the daily factor returns.

In unreported results, we find that the coefficients on the variables SMB and WML in regression (1) are significantly positive in the pre-announcement period, while the coefficient on the variable HML is significantly negative. In the post-announcement period the coefficient on SMB (WML) is significantly negative (positive), while the coefficient on HML is insignificantly different from zero.

We report average raw, rather than market-adjusted, returns for these intraday periods because of the lack of data on close-to-open and open-to-close market returns. Given that these periods are very short, raw and market-adjusted returns should be very similar.

While we assume that all purchases (sales) are made at the prevailing ask (bid), in reality the dollar amount that can actually be traded at these prices is limited by market depth. The smaller the market depth, the lower will be the dollar returns earned during the pre- and post-announcement periods.

We also applied this analysis to calendar-time returns, adjusting for risk using the four-factor model. In untabulated results we find that, after accounting for the bid-ask spread, the average daily pre-announcement (post-announcement) abnormal return remains reliably positive (negative).

The imposition of brokerage commissions of c percent lowers the absolute value of pre-announcement and post-announcement average market-adjusted returns to 0.94 − c and 0.85 − c percent, respectively. With average return standard errors (untabulated) of 0.36 and 0.44 for the pre- and post-announcement periods, respectively, the t-statistic for the after-commissions average return will exceed 1.65 (which corresponds to a 10% significance level) as long as c does not exceed 0.35 and 0.12, respectively, for the two periods.

The calculation parallels that for the full sample, given subsample average return standard errors of 0.41 and 0.50 (untabulated) for the pre- and post-announcement periods, respectively.

Consistent with this conjecture, Barber and Odean (2008) find a positive abnormal order imbalance for individual investors in stocks with large prior-day price movements.

We also test an alternative, information-based explanation, for our anomalous return results. This explanation requires that unexpectedly positive news comes out during the few days before the earnings announcements of our past winner sample, followed by unexpectedly negative news just afterwards. In untabulated analysis, we proxy for the release of positive pre-announcement news by upward revisions in analysts’ pre-announcement earnings forecasts. We proxy for negative post-announcement news by downward revisions in analysts’ post-announcement forecasts and/or negative earnings surprises. We find that <2% of our sample observations are characterized by both an upward revision in analysts’ forecasts in the week prior to the earnings announcements and a negative earnings surprise or downward forecast revision during the week thereafter. Not surprisingly, dropping these few observations from our sample does not significantly affect the magnitude of the pre- and post-announcement returns. The same is true if we eliminate all observations having positive pre-announcement analyst forecast revisions (regardless of the sign of the earnings surprise or post-announcement forecast revision, if any) or all observations having negative surprises or post-announcement forecast revisions (regardless of the sign of any pre-announcement revision). These results provide no support for an information-based explanation for the documented return pattern. This is not surprising, given that this potential explanation depends on investors not rationally anticipating that, on average, positive news will be released just before earnings announcements.

Using Nasdaq market data on known trade direction for 313 stocks during the September 1996 through September 1997 period, Ellis et al. (2000) find that the Lee and Ready (1991) algorithm correctly classifies 81.05% of the trades as buyer- or seller-initiated, the highest percentage among the three different classification schemes that they examine.

This ensures that the same set of announcements make up our small, medium-sized, and large trade subsamples.

The “normal” order imbalance is measured using data after the post-announcement period, rather than before, because the earlier period’s order imbalances are biased by our sample selection criteria.

This result means that small and medium-sized investors are increasing their trading during a time when the level of information asymmetry in the marketplace is likely to be heightened. Their behavior contrasts with the documented pattern for overall volume, which, as expected, decreases before earnings announcements (see, for example, Chae (2005)). This implies that either smaller investors are unaware of the magnitude of the adverse selection problem or its impact is outweighed by the attractiveness of the top performing stocks prior to their earnings announcements.

In contrast to our results, Barber and Odean (2008), Hirshleifer et al. (2008), and Lee (1992) find increased trading by small investors after the earnings announcement. They argue that the announced earnings capture small investors’ attention and motivate them to trade, whether the earnings news is good or bad. These analyses do not condition on prior stock returns. In cases where there has been a sharp prior price increase, we argue that small investors’ focus is drawn to earnings announcements before they occur and that they increase their trading at that time.

Barber et al. (2009) argue that the introduction of share price decimalization in 2001 and the increased use of computerized trading algorithms have made it more difficult to distinguish between the trades of small and large traders. To determine whether this has had an impact on the nature or significance of our results, we replicate our analysis separately for the 1993 through 2000 and 2001 through 2005 periods. In untabulated results, we find for each subperiod that the pre-announcement average abnormal order imbalance is significantly positive for the small and medium-sized traders and insignificantly different from zero for the large traders, just as for our full sample period. During the 1993 through 2000 subperiod the post-announcement average abnormal order imbalance is significantly negative for the large traders and insignificant for the small and medium-sized ones. None of the three post-announcement average abnormal order imbalances are reliably different from zero over the 2001 through 2005 subperiod.

The year-by-year returns reported in Fig. 1 bear out these differences.

References

Bagnoli, M., Kross, W., & Watts, S. (2002). The information in management’s expected earnings report date: A day late, a penny short. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(5), 1275–1296.

Ball, R., & Kothari, S. (1991). Security returns around earnings announcements. The Accounting Review, 66(4), 718–738.

Barber, B., & Odean, T. (2008). All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 785–818.

Barber, B., Odean, T., & Zhu, N. (2009). Do retail trades move markets? Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 151–186.

Berkman, H., & Truong, C. (2009). Event day 0? After-hours earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(1), 71–103. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/121582800/PDFSTART.

Bernard, V., & Thomas, J. (1989). Post-earnings-announcement drift: delayed price response or risk premium? Journal of Accounting Research, 27(supplement), 1–36.

Bradley, D., Jordan, B., & Ritter, J. (2003). The quiet period goes out with a bang. Journal of Finance, 58(1), 1–36.

Carhart, M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52(1), 57–82.

Chae, J. (2005). Trading volume, information asymmetry, and timing information. Journal of Finance, 60(1), 413–442.

Chari, V., Nathan, R., & Ofer, A. (1988). Seasonalities in security returns: The case of earnings announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 21(1), 101–121.

Dellavigna, S., & Pollet, J. (2009). Investor inattention and Friday earnings announcements. Journal of Finance, 64(2), 709–749. http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~sdellavi/wp/earnfr06-12-11NewTitle.pdf.

Doyle, J., Lundholm, R., & Soliman, M. (2003). The predictive value of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings. Review of Accounting Studies, 8(2–3), 145–174.

Ellis, K., Michaely, R., & O’Hara, M. (2000). The accuracy of trade classification rules: Evidence from Nasdaq. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 35(4), 529–551.

Fama, E., & French, K. (2008). Dissecting anomalies. Journal of Finance, 63(4), 1653–1678.

Foster, G., Olsen, C., & Shevlin, T. (1984). Earnings releases, anomalies, and the behavior of security returns. The Accounting Review, 59(4), 574–603.

Frazzini, A., & Lamont, O. (2007). The earnings announcement premium and trading volume. Working paper, National Bureau of Economic Research. http://ssrn.com/abstract=986940.

Gutierrez, R., & Kelley, E. (2008). The long-lasting momentum in weekly returns. Journal of Finance, 63(1), 415–447.

Hirshleifer, D., Hou, K., Teoh, S., & Zhang, Y. (2004). Do investors overvalue firms with bloated balance sheets? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 38(1–3), 297–331.

Hirshleifer, D., Myers, J., Myers, L., & Teoh, S. (2008). Do individual investors cause post-earnings announcement drift? Direct evidence from personal trades. Working paper, Irvine: University of California. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1120495.

Hou, K., Peng, L., & Xiong, W. (2008). A tale of two anomalies: the implication of investor inattention for price and earnings momentum. Working paper, Columbus: Ohio State University. http://ssrn.com/abstract=976394.

Jegadeesh, N. (1990). Evidence of predictable behavior of security returns. Journal of Finance, 45(3), 881–898.

Jegadeesh, N., & Titman, S. (1993). Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock market efficiency. Journal of Finance, 48(1), 65–91.

Lee, C. (1992). Earnings news and small traders: an intraday analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 15(2–3), 265–302.

Lee, C., & Ready, M. (1991). Inferring trade direction from intraday data. Journal of Finance, 46(2), 733–746.

Lehmann, B. (1990). Fads, martingales, and market efficiency. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105(1), 1–28.

Trueman, B., Wong, F., & Zhang, X.-J. (2003). Anomalous stock returns around internet firms’ earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 34(1–3), 249–271.

Acknowledgments

This paper has benefited from the comments of Richard Sloan, two anonymous referees, and workshop participants at Columbia University, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, NYU, Penn State University, UC Berkeley, and UC Irvine.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Aboody, D., Lehavy, R. & Trueman, B. Limited attention and the earnings announcement returns of past stock market winners. Rev Account Stud 15, 317–344 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9104-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9104-9