Abstract

Anecdotal and survey evidence suggest that managers take actions to avoid small negative earnings surprises because they fear disproportionate, negative stock-price effects. However, empirical research has failed to document an asymmetric pricing effect. We investigate investor relations costs as an alternative incentive for managers to avoid small negative earnings surprises. Guided by CFO survey evidence from Graham et al. (J Account Econ 40:3–73, 2005), we operationalize investor relations costs using conference call characteristics—call length, call tone, and earnings forecasting propensity around the conference call. We find an asymmetric increase (decrease) in call length (forecasting propensity) for firms that miss analyst expectations by 1 cent compared with changes in adjacent 1-cent intervals. We find no statistically significant evidence that call tone is asymmetrically more negative for firms that miss expectations by a penny. While these results provide some statistical evidence to confirm managerial claims documented in Graham et al. (J Account Econ 40:3–73, 2005) regarding the asymmetrically negative effects of missing expectations, our tests do not suggest severe economic effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, in Skinner and Sloan (2002), the market’s reaction to forecast errors (i.e., actual earnings minus the consensus analyst forecast) for growth stocks is quite symmetrical for forecast errors between zero and −0.7% of price and zero and 0.7% of price, suggesting no disproportionate penalty for small earnings misses. Forecast errors exceeding ±0.7% of price are not small misses. A growth stock with a price earnings ratio of 40 implies that quarterly earnings are 0.625% of price. Thus missing by 0.7% of price implies a forecast error of 112% of reported earnings.

miss0 denotes firm quarters where I/B/E/S actual earnings are equal to analyst expectations. make1 denotes firm quarters where I/B/E/S actual earnings exceed analyst expectations by 1 cent. miss2 denotes firm quarters where analyst expectations exceed I/B/E/S actual earnings by 2 cents. For brevity, we use “I/B/E/S earnings” to denote “I/B/E/S actual earnings” for the remainder of the paper.

Of course, a firm has the discretion to issue guidance outside of the hours of the conference call if analyst questions constrain the manager from doing so during the conference call. In our empirical specification, we examine managerial issuance of guidance in the 3-day window centered on the conference call to accommodate this potential substitution effect.

Brown et al. (2006) provide some evidence consistent with CFO concerns that overall uncertainty about firm prospects increases when a firm misses earnings. In particular, they show increases in cost of capital (as proxied by the probability of informed trading) when firms miss earnings. Our investigation provides a potential explanation for their result, i.e., management is unable to discuss future earnings.

Research finds that accruals are used to achieve earnings targets only when earnings targets are defined in terms of 1-cent intervals (Ayers et al. 2006), suggesting that a 1-cent definition of “small” is the most powerful setting to perform our empirical tests.

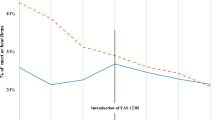

This figure assumes that conference call length is inversely related to earnings surprise. That is, conference calls get longer as earnings surprise becomes more negative. In the process of testing H1, we also offer evidence with regard to empirical validity of this assumption.

These inequalities imply that under our hypothesis, β3 will reside above the midpoint between the adjacent bin coefficients β2 and β4, and β4 will reside below the midpoint between the adjacent bin coefficients β3 and β5. Under the null hypothesis, β3 and β4 will not differ from the midpoints between adjacent bins.

Durtschi and Easton (2005) challenge the notion that kinks in earnings distributions in and of themselves are evidence of managers achieving earnings targets. They caution that scaling and analyst optimism/pessimism could yield a kink in the distribution of earnings. In addition, Beaver et al. (2007) suggest that taxes contribute to the discontinuity in the earnings distribution around zero. Our study provides insights into this debate by looking for asymmetric conference call characteristics for firms just missing and just meeting earnings targets because a discontinuity that results from scaling or taxes should not produce investor-relations consequences.

The Harvard-IV dictionary definitions on the General Inquirer’s web site provide a complete word list http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~inquirer/.

We use the First Call database to assess whether future earnings guidance was issued. Identifying whether the firm discussed future earnings guidance specifically during the conference call is prohibitively costly as it would require the reading of entire transcripts for our sample firms. However, even in the event we were able to identify whether firms issued guidance during the conference call and found results consistent with H3, an alternative hypothesis could be that managers are not really constrained and simply issue guidance outside of the conference call window. Using the three-day window centered on the conference call provides a more comprehensive test.

Atiase et al. (2005) include in their analysis the sign and magnitude of the guidance issued as well as whether the sign of the guidance was consistent or inconsistent with the sign of the earnings surprise. By construction, their analysis requires point and range estimates of future earnings so as to quantify guidance surprises. We do not require this restriction and therefore do not measure the sign or magnitude of the earnings guidance because we are concerned with whether guidance was issued, instead of the precision of the guidance issued.

We report the empirical results based on the length and the tone of the entire conference call in the paper. Matsumoto et al. (2006) suggest a substitute relation between information provided in the management presentation versus the question and answer section. In untabulated analyses, we also examine the length and tone of the presentation section and the question and answer (Q&A) section separately. For call length, we find the miss-by-a-penny effect for the Q&A section only, suggesting the managers do not preempt the demand of analysts for information and increase the information disclosed during the presentation section. For call tone, the reported results for the entire call hold for both subsets of the call.

Management retains some flexibility in terms of which analysts they choose to speak with. If managers choose to have dialogs with analysts who carry favorable views of the firm (Mayew 2008), it can reduce the negativity in the tone of the dialog.

To calculate predicted probabilities, we set all continuous independent variables equal to the sample means and all indicator variables equal to zero except for the forecast error bin of interest.

References

Atiase, R., Li, H., Supattarakul, S., & Tse, S. (2005). Market reaction to multiple contemporaneous earnings signals: Earnings announcements and future earnings guidance. Review of Accounting Studies, 10, 497–525.

Ayers, B., Jiang, X., & Yeung, P. (2006). Discretionary accruals and earnings management: An analysis of pseudo earnings targets. The Accounting Review, 81, 617–652.

Baber, W., & Kang, S. (2002). The impact of split adjusting and rounding on analysts’ forecast error calculations. Accounting Horizons, 16, 277–289.

Beaver, W., McNichols, M., & Nelson, K. (2007). An alternative interpretation of the discontinuity in the earnings distribution. Review of Accounting Studies, 12, 525–556.

Bowen, R., Davis, A., & Matsumoto, D. (2002). Do conference calls affect analysts’ forecasts? The Accounting Review, 77, 285–316.

Brown, S., Hillegeist, S., & Lo, K. (2004). Conference calls and information asymmetry. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 37, 343–366.

Brown, S., Hillegeist, S., & Lo, K. (2006). The effect of meeting or missing earnings expectations on information asymmetry. Working paper, Emory University, INSEAD, and University of British Columbia.

Burgstahler, D., & Dichev, I. (1997). Earnings management to avoid earnings decreases and losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24, 99–126.

Burgstahler, D., & Eames, M. (2006). Management of earnings and analysts’ forecasts to achieve zero and small positive earnings surprises. Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting, 33, 633–652.

Bushee, B., Matsumoto, D., & Miller, G. (2003). Open versus closed conference calls: the determinants and effects of broadening access to disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 34, 149–180.

Chen, S., Defond, M., & Park, C. (2002). Voluntary disclosure of balance sheet information in quarterly earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33, 229–251.

Davis, A., Piger, J. & Sedor, L. (2007). Beyond the numbers: An analysis of optimistic and pessimistic language in earnings press releases. Working Paper, University of Oregon and University of Washington.

Dechow, P., Richardson, S., & Tuna, I. (2003). Why are earnings kinky? An examination of the earnings management explanation. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 355–384.

Defond, M., & Hung, M. (2003). An empirical analysis of analysts’ cash flow forecasts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 35, 73–100.

Degeorge, F., Patel, J., & Zeckhauser, R. (1999). Earnings management to exceed thresholds. Journal of Business, 72, 1–34.

Doyle, J., Lundholm, R., & Soliman, M. (2003). The predictive value of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 145–174.

Doyle, J., Lundholm, R., & Soliman, M. (2006). The extreme future stock returns following I/B/E/S earnings surprise. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 849–887.

Durtschi, C., & Easton, P. (2005). Earnings management? The shapes of the frequency distributions of earnings metrics are not evidence Ipso Facto. Journal of Accounting Research, 43, 557–592.

Frankel, R., Johnson, M., & Skinner, D. (1999). An empirical examination of conference calls as a voluntary disclosure medium. Journal of Accounting Research, 37, 133–150.

Freeman, R., & Tse, S. (1992). A nonlinear model of security price responses of unexpected earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 30, 185–209.

Graham, J., Harvey, C., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40, 3–73.

Hand, J. (2002). Discussion of “Earnings surprises, growth expectations, and stock prices, or, don’t let and earnings torpedo sink your portfolio”. Review of Accounting Studies, 7, 313–318.

Hutton, A., Miller, G., & Skinner, D. (2003). The role of supplementary statements with management earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 867–890.

Kinney, W., Burgstahler, D., & Martin, R. (2002). Earnings surprise “materiality” as measured by stock returns. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 1297–1329.

Lipschutz, N. (2000). Point of view: when a penny is not just a penny. Dow Jones News Service, July 6.

Matsumoto, D. (2002). Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. The Accounting Review, 77, 483–514.

Matsumoto, D., Pronk, M., & Roelofsen, E. (2006). Managerial disclosure vs. analyst inquiry: an empirical investigation of the presentation and discussion portions of earnings-related conference calls. Working paper, University of Washington, Tilburg University, and RSM Erasmus University.

Mayew, W. (2008). Evidence of management discrimination among analysts during earnings conference calls. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 627–659.

Payne, J., & Thomas, W. (2003). The implications of using stock split adjusted I/B/E/S data in empirical research. The Accounting Review, 78, 1046–1049.

Skinner, D. (1994). Why firms voluntarily disclose bad news. Journal of Accounting Research, 32, 38–60.

Skinner, D., & Sloan, R. (2002). Earnings surprises, growth expectations, and stock returns or don’t let an earnings torpedo sink your portfolio. Review of Accounting Studies, 7, 289–312.

Tasker, S. (1998). Bridging the information gap: Quarterly conference calls as a medium for voluntary disclosure. Review of Accounting Studies, 3, 137–167.

Tetlock, P. (2007). Giving content to investor sentiment: The role of media in the stock market. Journal of Finance, 62, 1139–1168.

Tetlock, P., Saar-Tsechansky, M., & Macskassy, S. (2008). More than words: Quantifying language to measure firm’s fundamentals. Journal of Finance, 63, 1437–1467.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the comments of Doron Nissim (editor), two anonymous referees, Shane Dikolli, Yonca Ertimur, John Hand, Nicole Thorne Jenkins, Ben Lansford, Ron King, Raj Mashruwala, Jenny Tucker, Tzachi Zach, seminar participants at Washington University in St. Louis, the 2007 Southeast Summer Accounting Research Conference, and the 2007 American Accounting Association Annual Meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Data availability

The data used in this study are from the public sources identified in the text.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frankel, R., Mayew, W.J. & Sun, Y. Do pennies matter? Investor relations consequences of small negative earnings surprises. Rev Account Stud 15, 220–242 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9089-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9089-4