Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effect of esketamine nasal spray on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in patients with major depressive disorder having active suicidal ideation with intent (MDSI).

Methods

Patient-level data from two phase 3 studies (ASPIRE I; ASPIRE II) of esketamine + standard of care (SOC) in patients (aged 18–64 years) with MDSI, were pooled. PROs were evaluated from baseline through end of the double-blind treatment phase (day 25). Outcome assessments included: Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), Quality of Life (QoL) in Depression Scale (QLDS), European QoL Group-5-Dimension-5-Level (EQ-5D-5L), and 9-item Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-9). Changes in BHS and QLDS scores (baseline to day 25) were analyzed using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM).

Results

Pooled data for esketamine + SOC (n = 226; mean age: 40.5 years, 59.3% females) and placebo + SOC (n = 225; mean age: 39.6 years, 62.2% females) were analyzed. Mean ± SD change from baseline to day 25, esketamine + SOC vs placebo + SOC (least-square mean difference [95% CI] based on MMRM): BHS total score, − 7.4 ± 6.7 vs − 6.8 ± 6.5 [− 1.0 (− 2.23, 0.21)]; QLDS score, − 14.4 ± 11.5 vs − 12.2 ± 10.8 [− 3.1 (− 5.21, − 1.02)]. Relative risk (95% CI) of reporting perceived problems (slight to extreme) in EQ-5D-5L dimensions (day 25) in esketamine + SOC vs placebo + SOC: mobility [0.78 (0.50, 1.20)], self-care [0.83 (0.55, 1.27)], usual activities [0.87 (0.72, 1.05)], pain/discomfort [0.85 (0.69, 1.04)], and anxiety/depression [0.90 (0.80, 1.00)]. Mean ± SD changes from baseline in esketamine + SOC vs placebo + SOC for health status index: 0.23 ± 0.21 vs 0.19 ± 0.22; and for EQ-Visual Analogue Scale: 24.0 ± 27.2 vs 19.3 ± 24.4. At day 25, mean ± SD in domains of TSQM-9 scores in esketamine + SOC vs placebo + SOC were: effectiveness, 67.2 ± 25.3 vs 56.2 ± 26.8; global satisfaction, 69.9 ± 25.2 vs 56.3 ± 27.8; and convenience, 74.0 ± 19.4 vs 75.4 ± 18.7.

Conclusion

These PRO data support the patient perspective of the effect associated with esketamine + SOC in improving health-related QoL in patients with MDSI.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: ASPIRE I, NCT03039192 (Registration date: February 1, 2017); ASPIRE II, NCT03097133 (Registration date: March 31, 2017).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is a leading cause of disability affecting nearly 300 million people globally and is a major contributor to suicide deaths worldwide [1]. In the United States, major depressive disorder (MDD) affects 7.8% of the adult population annually [2], with an estimated 31% of MDD patients experiencing past-year suicidal ideation [3]. Prior studies have demonstrated that individuals with MDD and suicidal ideation are often associated with poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL), greater work productivity loss and activity impairment than those without suicidal ideation [4, 5].

Current standard of care (SOC) includes inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and optimized oral antidepressant therapy for patients at risk for suicide [6, 7]. Initial hospitalization aims to provide a safe environment for evaluation and initiation of treatment during emergencies; however, the risks for suicide remain high following discharge [8, 9]. Furthermore, standard antidepressants usually require approximately one month or more for antidepressant effects to manifest, hence their utility in such situations remains limited [7, 10].

Esketamine nasal spray plus comprehensive SOC has been approved for treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with MDD having active suicidal ideation with intent by the US Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency, and other global health authorities. These approvals were based on efficacy and safety results from two identically designed, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase 3 studies, ASPIRE I (NCT03039192) and ASPIRE II (NCT03097133) [11, 12]. In both studies, esketamine nasal spray plus SOC was associated with a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms of MDD in patients with active suicidal ideation with intent at 24 h after the first dose compared with a matched placebo nasal spray plus SOC, as assessed by clinician-rated outcome measures [11, 12]. The safety profile of esketamine in the high-risk patient population reported in these studies was consistent with the established safety profile of esketamine nasal spray [11, 12].

Clinically significant impairment in HRQoL, including perceived physical and mental functioning, are well documented among patients with MDD [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Patients with MDD reported greater limitations in physical, social, and role functioning, including work, household, and school activities than patients with many other chronic general medical conditions [19,20,21]. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were implemented in the ASPIRE clinical trials to capture some aspects of patient burden.

Inclusion of PROs in clinical trials also provides insights regarding unique patient perspectives, which can be used to help clinicians arrive at more informed treatment decisions, particularly for chronic, disabling conditions [22,23,24]. PROs play a crucial role in capturing the patient perspective of treatment and assist with examining the effects of treatment interventions in MDD and in predicting relapse [25, 26]. To obtain further insight into the efficacy of esketamine nasal spray, we evaluated its impact over time from a patient’s perspective through PROs using pooled data from the ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II trials.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data for this post hoc analysis were pooled from ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II, two identically designed, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase 3 studies that evaluated efficacy and safety of esketamine nasal spray vs matched placebo nasal spray co-administered with a newly optimized oral antidepressant therapy and initial hospitalization as SOC. The study design and methodology have been published [11, 12, 27]. In brief, an initial screening phase conducted within 48 h prior to day 1 dose was followed by a 4-week double-blind treatment phase wherein patients were randomized (1:1) to receive esketamine (84 mg) nasal spray plus SOC or placebo plus SOC twice weekly. The studies included patients (aged 18–64 years) with a diagnosis of MDD (as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition [DSM-5] criteria) [28] without psychosis, as confirmed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; current suicidal ideation with intent within 24 h prior to randomization, as confirmed by responding ‘Yes’ to the questions “Think about suicide?” and “Intend to act on thoughts of killing yourself?”; in need of acute psychiatric hospitalization due to imminent risk of suicide; and with a Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score > 28 pre-dose on day 1.

Both trials were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki International Conference on Harmonization, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. All patients provided written informed consent. Study protocols and amendments were approved by independent review board or ethics committee for each study site.

Patient-reported outcomes

The trials included the following PRO instruments that capture relevant concepts from the patients’ perspectives: The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), the QoL in Depression Scale (QLDS), the European QoL Group, 5-Dimension, 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L), and the 9-item Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-9).

All PRO measures were self-administered by the patients and data were collected using an electronic tablet. All PROs were evaluated from baseline through the end of the double-blind treatment phase (day 25).

Beck Hopelessness Scale [29, 30]

The BHS is a self-reported measure to assess one’s level of negative expectations or pessimism regarding the future. It consists of 20 true/false items that examine the respondent’s attitude over the past week by either endorsing a pessimistic statement or denying an optimistic statement. These items fall within 3 domains: 1. feelings about the future; 2. loss of motivation; and 3. future expectations. For every statement, each response is assigned a score of 0 or 1. The total BHS score is a sum of item responses and ranges from 0 to 20 (Minimal: 0–3, Mild: 4–8, Moderate: 9–14, and Severe: 15–20), with a higher score representing a higher level of hopelessness. BHS score of ≥ 9 have been found to be predictive of eventual suicide in depressed individuals with suicidal ideation [31,32,33,34,35].

Quality of Life in Depression Scale [36]

The QLDS is a disease specific, 34-item questionnaire designed to assess HRQoL in patients with MDD. Patients choose “true”/“not true” for each item based on their health “at the present time,” for a possible total score from 0 (good quality of life [QoL]) to 34 (poor QoL). A meaningful change threshold of 8 points has been suggested for depressed patients [37].

European Quality of Life Group, 5-Dimension, 5-Level [38]

The EQ-5D-5L, a standardized 2-part instrument for assessing HRQoL, consists of the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system and the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS). EQ-5D-5L descriptive system has 5 dimensions of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) scored on five levels based on perceived problems (Level 1: none to Level 5: extreme). Patients selected an answer for each dimension considering the response that best matched his or her health “today”. Each dimension’s response was used to generate a health status index (HSI; 0 [dead] to 1 [full health]). Changes in HSI on the order of 0.03–0.07 are recognized as a threshold for meaningful change for an individual patient [39, 40]. Patients also self-rated their overall health status from 0 (worst health) to 100 (best health) on the EQ-VAS. Changes in EQ-VAS on the order of 7 to 10 are recognized as a threshold for meaningful change for an individual patient [41].

Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication, 9 Items [42]

TSQM-9 is 9-item PRO instrument assessing patients’ satisfaction with the medication and covers the domains of effectiveness, convenience, and global satisfaction. Each domain is scored from 0 to 100 with lower scores indicating lower satisfaction. The recall period is “the last 2–3 weeks.”

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were provided for PROs collected at baseline and day 25 (TSQM-9 was collected at day 25 only).

The change from baseline to day 25 in BHS and QLDS scores was estimated using least squares (LS) means based on a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) on observed case data with baseline score as covariate, and day, treatment, analysis center, SOC antidepressant treatment as randomized (antidepressant monotherapy, or antidepressant plus augmentation therapy) and day-by-treatment interaction as fixed effects and a random subject effect. The corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for the treatment difference were provided. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random.

Relative risks (95% CI) were provided to compare the risks of reporting perceived problems in each dimension of EQ-5D-5L (levels 2–5, indicating slight to extreme problems) at day 25 between two treatment groups. Proportion of patients with clinically meaningful improvement in PROs at day 25 were summarized, defined as change from baseline by the meaningful change threshold or greater for the QLDS, HSI, EQ-VAS at day 25, and proportion of patients with a BHS score of < 9 (minimal or mild hopelessness) at day 25. Estimates of the treatment difference in proportions and 95% CIs were determined.

Since the PROs were not primary endpoints, sample size for each study was calculated using the primary endpoint (MADRS total score). Assuming an effect size of 0.45 for the change in MADRS total score between esketamine plus SOC and placebo plus SOC, a two-sided significance level of 0.05, and a drop-out rate at 24 h of 5%, approximately 112 patients were required to be randomly assigned to each treatment group to achieve 90% power.

The full efficacy analysis set for all PRO analyses included all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of double-blind study medication and had both a baseline and a post-baseline evaluation for the MADRS total score or Clinical Global Impression–Severity of Suicidality–revised.

The SAS version 9.4 was used to perform the statistical data analysis in this study.

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

The combined data from the ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II studies resulted in 451 patients with MDD with suicidal ideation included in the full efficacy analysis set, with 226 randomized to esketamine + SOC and 225 to placebo + SOC. In this pooled analysis, baseline demographics and clinical characteristics across treatment arms were similar (Table 1). Mean patient age in the esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC groups was 40.5 and 39.6 years, and the proportion of women was 59.3% and 62.2%, respectively. Baseline scores for the PROs were also comparable (Table 1). Further details regarding the demographics, baseline clinical and psychiatric information have been published previously for this pooled population [27].

Patient-reported outcomes

Beck Hopelessness Scale

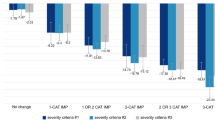

At baseline, mean BHS total scores were 15.4 for esketamine + SOC group and 15.8 for placebo + SOC group, indicating severe hopelessness. At day 25, the mean (SD) of the BHS total scores were 8.2 (6.6), and 8.9 (6.6) for patients treated with esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC, respectively. The mean (SD) change from baseline to day 25 in BHS total score for esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC groups was − 7.4 (6.7) vs − 6.8 (6.5) and difference of least squares mean (95% CI) was − 1.0 (− 2.23, 0.21) (Table 2; Fig. 1). Overall, 112 (49.6%) esketamine + SOC treated patients compared to 100 (44.4%) placebo + SOC treated patients had clinically significant improvement in BHS total score at day 25 (BHS < 9 minimal or mild hopelessness; difference in % [95% CI]: 5.1 [− 4.09, 14.31]; Table 3).

Mean difference in change from baseline at day 25 in BHS total score and QLDS total score (pooled data). The estimates and CIs are based on MMRM analysis. BHS Beck Hopelessness Scale; CI confidence interval; ESK esketamine; LS least squares; MMRM mixed-effects model for repeated measures; QLDS Quality of Life in Depression Scale; SOC standard of care

Quality of Life in Depression Scale

At baseline, the mean QLDS score was 27.0 for both treatment arms. At day 25, the mean (SD) of the QLDS scores were 12.6 (11.3) and 14.7 (10.8) for patients treated with esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC, respectively. The mean (SD) change from baseline to day 25 in QLDS score for esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC groups was − 14.4 (11.5) vs − 12.2 (10.8) and difference of least squares mean (95% CI) was − 3.1 (− 5.21, − 1.02) (Table 2; Fig. 1). At day 25, 132 (58.4%) patients from the esketamine + SOC group vs 113 (50.25%) patients from the placebo + SOC group had at least 8 points reduction in QLDS score from baseline (difference in % [95% CI]: 8.2 [− 0.98, 17.35]; Table 3).

European Quality of Life Group, 5-Dimension, 5-Level

The relative risk (95% CI) of reporting perceived problems in EQ-5D-5L (levels 2–5, indicating slight to extreme problems) at day 25 in esketamine + SOC compared with placebo + SOC group in each dimension were: mobility, 0.78 (0.50, 1.20); self-care, 0.83 (0.55, 1.27); usual activities, 0.87 (0.72, 1.05); pain/discomfort, 0.85 (0.69, 1.04); anxiety/depression, 0.90 (0.80, 1.00) (Fig. 2). At day 25, for all dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) of EQ-5D-5L, a lesser proportion of patients treated with esketamine + SOC vs placebo + SOC reported having any perceived problems (slight [Level 2] to extreme problems [Level 5]) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

At baseline, the mean (SD) HSI was 0.56 (0.20) for both treatment arms. At day 25, the mean (SD) of the HSI were 0.79 (0.17) and 0.76 (0.18) for patients treated with esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC, respectively. The mean (SD) change from baseline to day 25 in HSI for esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC groups was 0.23 (0.21) vs 0.19 (0.22) (Table 2). At day 25, 168 (74.3%) patients treated with esketamine + SOC and 147 (65.3%) patients treated with placebo + SOC reported HSI change from baseline of ≥ 0.03. While in 152 (67.3%) and 134 (59.6%) patients treated with esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC, respectively, a change of ≥ 0.07 was reported (Table 3).

At baseline, the mean EQ-VAS scores were 40.1 (23.6) for esketamine + SOC group and 40.2 (23.8) for placebo + SOC group. At day 25, the mean (SD) of the EQ-VAS scores were 64.3 (22.3) and 60.5 (22.4) for patients treated with esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC, respectively. The mean (SD) change from baseline to day 25 in EQ-VAS score for esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC groups was 24.0 (27.2) vs 19.3 (24.4) (Table 2), with 139 (61.5%) patients receiving esketamine + SOC and 126 (56.0%) patients receiving placebo + SOC reporting EQ-VAS change from baseline of ≥ 7 (Table 3). While in 137 (60.6%) and 121 (53.8%) patients treated with esketamine + SOC and placebo + SOC, respectively, a change of ≥ 10 was reported (Table 3).

Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication, 9 Items

The mean (SD) at day 25 in various domains of TSQM-9 scores in patients treated with esketamine + SOC vs placebo + SOC were: effectiveness, 67.2 (25.3) vs 56.2 (26.8); global satisfaction, 69.9 (25.2) vs 56.3 (27.8); convenience, 74.0 (19.4) vs 75.4 (18.7) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Both phase 3 global studies (ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II) have demonstrated clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms evaluated as reduction in MADRS total score at 24 h post-first dose in MDD population with active suicidal ideation with intent [11, 12]. The results obtained from the recent pooled analysis were also consistent with those of the individual trials [27]. The current post hoc analysis of PROs supplements these efficacy results obtained using clinician-reported measures of depression. Overall, the findings of this analysis suggested that from the patient perspective (as assessed by PROs), esketamine + SOC treatment compared with placebo + SOC treatment led to numerically greater improvements in feelings of hopelessness assessed with the BHS, global satisfaction and effectiveness as assessed by the TSQM-9, and HRQoL as assessed with the EQ-5D-5L. Improvements in depression specific QoL as assessed with the QLDS showed more notable changes at day 25.

The patient-reported data collected via an online patient community platform, PatientsLikeMe, identified feelings of hopelessness, loneliness, anhedonia, and social anxiety to be significantly associated with suicidal ideation in patients with MDD [43]. Improvements in hopelessness, as measured by the BHS scores, was observed in both treatment groups. However, esketamine + SOC treatment showed numerically greater reduction in feelings of hopelessness prevalent among patients with active suicidal ideation and intent and numerically higher percentage of patients with scores of below 9 on the BHS. A greater proportion of patients showed improvements in QLDS (QLDS change from baseline ≤ − 8; Table 3) and EQ-5D-5L scores post-treatment with esketamine, suggesting an overall improvement in HRQoL. Patients’ satisfaction with the medication, as measured by TSQM-9 at day 25, provides an assessment of treatment effectiveness from the patient’s perspective, with numerically higher levels of satisfaction with effectiveness and global satisfaction among esketamine-treated patients than placebo-treated patients. There was no difference in their assessment of convenience, which is not surprising given that both treatment groups were taking study medication twice a week via intranasal administration.

Per recent FDA guidance [44], the collection of patient experience data (including information collected via PROs) is becoming increasingly important for the enhancement of regulatory decision making, in order to address patient needs. Here, we show that PROs supplement the use of traditional clinician rating scales to further support impact of esketamine in the treatment of patients with MDD with suicidal ideation and intent.

Some limitations of this study should be considered. Patients enrolled in clinical studies may differ from those in practice, so the generalizability of the study results may be limited particularly since patients in the ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II were provided comprehensive and optimized clinical care such as hospitalization and frequent clinical assessment which may have influenced PROs. The relationship with other sociodemographic variables, such as age, gender, race, or ethnicity, was not investigated. The post hoc nature of this analysis is another potential limitation.

In conclusion, these PRO data provide support for the patient perspective of effect associated with esketamine + SOC treatment in improving HRQoL in MDD patients with suicidal ideation and intent.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access [YODA] Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

References

World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. World Health Organization.

Judd, L. L., Schettler, P. J., & Rush, A. J. (2016). A brief clinical tool to estimate individual patients’ risk of depressive relapse following remission: Proof of concept. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1140–1146. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111462

Voelker, J., Kuvadia, H., Cai, Q., Wang, K., Daly, E., Pesa, J., Connolly, N., Sheehan, J. J., & Wilkinson, S. T. (2021). United States national trends in prevalence of major depressive episode and co-occurring suicidal ideation and treatment resistance among adults. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 5, 1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100172

Benson, C., Singer, D., Carpinella, C. M., Shawi, M., & Alphs, L. (2021). The health-related quality of life, work productivity, healthcare resource utilization, and economic burden associated with levels of suicidal ideation among patients self-reporting moderately severe or severe major depressive disorder in a national survey. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 17, 111–123. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S229530

Jaffe, D. H., Rive, B., & Denee, T. R. (2019). The burden of suicidal ideation across Europe: A cross-sectional survey in five countries. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 15, 2257–2271. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S204265

Weber, A. N., Michail, M., Thompson, A., & Fiedorowicz, J. G. (2017). Psychiatric emergencies: Assessing and managing suicidal ideation. Medical Clinics of North America, 101(3), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2016.12.006

Wasserman, D., Rihmer, Z., Rujescu, D., Sarchiapone, M., Sokolowski, M., Titelman, D., Zalsman, G., Zemishlany, Z., & Carli, V. (2012). The European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention. European Psychiatry, 27(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.06.003

Rush, A. J., Trivedi, M. H., Ibrahim, H. M., Carmody, T. J., Arnow, B., Klein, D. N., Markowitz, J. C., Ninan, P. T., Kornstein, S., Manber, R., Thase, M. E., Kocsis, J. H., & Keller, M. B. (2003). The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 54(5), 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8

Chung, D., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Wang, M., Swaraj, S., Olfson, M., & Large, M. (2019). Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open, 9(3), e203883. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023883

Pompili, M., Serafini, G., Innamorati, M., Ambrosi, E., Giordano, G., Girardi, P., Tatarelli, R., & Lester, D. (2010). Antidepressants and suicide risk: A comprehensive overview. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 3(9), 2861–2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph3092861

Fu, D.-J., Ionescu, D. F., Li, X., Lane, R., Lim, P., Sanacora, G., Hough, D., Manji, H., Drevets, W. C., & Canuso, C. M. (2020). Esketamine nasal spray for rapid reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms in patients who have active suicidal ideation with intent: double-blind, randomized study (ASPIRE I). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.19m13191

Ionescu, D. F., Fu, D.-J., Qiu, X., Lane, R., Lim, P., Kasper, S., Hough, D., Drevets, W. C., Manji, H., & Canuso, C. M. (2021). Esketamine nasal spray for rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder who have active suicide ideation with intent: Results of a phase 3, double-blind, randomized study (ASPIRE II). International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyaa068

Saragoussi, D., Christensen, M. C., Hammer-Helmich, L., Rive, B., Touya, M., & Haro, J. M. (2018). Long-term follow-up on health-related quality of life in major depressive disorder: A 2-year European cohort study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 1339–1350. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S159276

Knight, M. J., Lyrtzis, E., & Baune, B. T. (2020). The association of cognitive deficits with mental and physical quality of life in major depressive disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 97, 152147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152147

Noto, S., Wake, M., Mishiro, I., Hammer-Helmich, L., Ren, H., Moriguchi, Y., Fujikawa, K., & Fernandez, J. (2022). Health-related quality of life over 6 months in patients with major depressive disorder who started antidepressant monotherapy. Value in Health Regional Issues, 30, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2021.12.001

Vancampfort, D., Kimbowa, S., Schuch, F., & Mugisha, J. (2021). Physical activity, physical fitness and quality of life in outpatients with major depressive disorder versus matched healthy controls: Data from a low-income country. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 802–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.092

Judd, L. L., Schettler, P. J., Solomon, D. A., Maser, J. D., Coryell, W., Endicott, J., & Akiskal, H. S. (2008). Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 108(1–2), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.014

IsHak, W. W., Greenberg, J. M., Balayan, K., Kapitanski, N., Jeffrey, J., Fathy, H., Fakhry, H., & Rapaport, M. H. (2011). Quality of life: The ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 19(5), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229.2011.614099

Hays, R. D., Wells, K. B., Sherbourne, C. D., Rogers, W., & Spritzer, K. (1995). Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130011002

Wells, K. B., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1999). Functioning and utility for current health of patients with depression or chronic medical conditions in managed, primary care practices. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(10), 897–904. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.897

Fried, E. I., & Nesse, R. M. (2014). The impact of individual depressive symptoms on impairment of psychosocial functioning. PLoS One, 9(2), e90311. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090311

Nunes Amaral, L. A., Ivanov, P. C., Aoyagi, N., Hidaka, I., Tomono, S., Goldberger, A. L., Stanley, H. E., & Yamamoto, Y. (2001). Behavioral-independent features of complex heartbeat dynamics. Physical Review Letters, 86(26 Pt 1), 6026–6029. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.6026

Calvert, M., Blazeby, J., Revicki, D., Moher, D., & Brundage, M. (2011). Reporting quality of life in clinical trials: A CONSORT extension. Lancet, 378(9804), 1684–1685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61256-7

Doward, L. C., Gnanasakthy, A., & Baker, M. G. (2010). Patient reported outcomes: Looking beyond the label claim. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-89

Ishak, W. W., Greenberg, J. M., & Cohen, R. M. (2013). Predicting relapse in major depressive disorder using patient-reported outcomes of depressive symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the Individual Burden of Illness Index for Depression (IBI-D). Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.048

IsHak, W. W., Mirocha, J., Pi, S., Tobia, G., Becker, B., Peselow, E. D., & Cohen, R. M. (2014). Patient-reported outcomes before and after treatment of major depressive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 16(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/rcohen

Canuso, C. M., Ionescu, D. F., Li, X., Qiu, X., Lane, R., Turkoz, I., Nash, A. I., Lopena, T. J., & Fu, D. J. (2021). Esketamine nasal spray for the rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 41(5), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001465

Malhotra, P., Ramakrishnan, A., Anand, G., Vig, L., Agarwal, P., & Shroff, G. (2016). LSTM-based encoder-decoder for multi-sensor anomaly detection. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1607.00148.

Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037562

Beck, A. T. (1988). The Psychological Corporation. Beck Hopelessness Scale.

Brown, G. K., Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Grisham, J. R. (2000). Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 371–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.371

Wolfe, K. L., Nakonezny, P. A., Owen, V. J., Rial, K. V., Moorehead, A. P., Kennard, B. D., & Emslie, G. J. (2019). Hopelessness as a predictor of suicide ideation in depressed male and female adolescent youth. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 49(1), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12428

Nimeus, A., Traskman-Bendz, L., & Alsen, M. (1997). Hopelessness and suicidal behavior. Journal of Affective Disorders, 42(2–3), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01404-8

Qiu, T., Klonsky, E. D., & Klein, D. N. (2017). Hopelessness predicts suicide ideation but not attempts: A 10-year longitudinal study. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 47(6), 718–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12328

Beck, A. T., Brown, G., Berchick, R. J., Stewart, B. L., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(2), 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.147.2.190

McKenna, S. P., & Hunt, S. M. (1992). A new measure of quality of life in depression: Testing the reliability and construct validity of the QLDS. Health Policy, 22(3), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(92)90005-v

Rozjabek, H., Li, N., Hartmann, H., Fu, D. J., Canuso, C., & Jamieson, C. (2022). Assessing the meaningful change threshold of quality of life in depression scale using data from two phase 3 studies of esketamine nasal spray. Journal of Patient Reported Outcomes, 6(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-022-00453-y

Herdman, M., Gudex, C., Lloyd, A., Janssen, M., Kind, P., Parkin, D., Bonsel, G., & Badia, X. (2011). Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research, 20(10), 1727–1736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

Gerhards, S. A., Huibers, M. J., Theunissen, K. A., de Graaf, L. E., Widdershoven, G. A., & Evers, S. M. (2011). The responsiveness of quality of life utilities to change in depression: A comparison of instruments (SF-6D, EQ-5D, and DFD). Value Health, 14(5), 732–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2010.12.004

Walters, S. J., & Brazier, J. E. (2005). Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Quality of Life Research, 14(6), 1523–1532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-7713-0

Pickard, A. S., Neary, M. P., & Cella, D. (2007). Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-70

Atkinson, M. J., Sinha, A., Hass, S. L., Colman, S. S., Kumar, R. N., Brod, M., & Rowland, C. R. (2004). Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-12

Borentain, S., Nash, A. I., Dayal, R., & DiBernardo, A. (2020). Patient-reported outcomes in major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation: A real-world data analysis using PatientsLikeMe platform. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 384. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02758-y

Li, P., Yu, L., Yang, J., Lo, M. T., Hu, C., Buchman, A. S., Bennett, D. A., & Hu, K. (2019). Interaction between the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and fractal degradation. Neurobiology of Aging, 83, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.08.023

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Shweta Pitre, CMPP and Vaibhav Deshpande, PhD (SIRO Clinpharm Pvt. Ltd.) for providing writing assistance, which was funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC. Ellen Baum, PhD (Janssen Global Services, LLC) for additional editorial support for this manuscript.

Funding

The studies presented in this report were supported by Janssen Research & Development, LLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CJ: study design and implementation, analysis and interpretation of results, development of manuscript. CMC: study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and review of the manuscript. DFI: protocol writing and execution, data collection, contribution to paper writing/drafts. RL: participated in study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and review of the manuscript. XQ: data analysis, contribution to paper writing/drafts HR: analysis and interpretation of results, development of manuscript. PM: data collection, contribution to paper writing/drafts. DJF: participated in study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

H. Rozjabek, D-J. Fu, D. F. Ionescu, R. Lane, C. M. Canuso, X. Qiu and C. Jamieson are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC and may own stock or stock options. P. Molero is supported by Clinica Universidad de Navarra and has received research grants from the Ministry of Education (Spain), the Government of Navarra (Spain) and the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health and AstraZeneca; he is a clinical consultant for MedAvante-ProPhase and has received lecture honoraria from and/or has been a consultant for AB-Biotics, Adept Field Solutions, Guidepoint, Janssen, Novumed, Roland Berger and Scienta. From 2015, PM has been the principal investigator at Clinica Universidad de Navarra of several studies supported by Janssen about the efficacy and safety of esketamine for Major depressive disorder.

Ethical approval

The protocol and amendments were approved by local independent ethics committees/Institutional Review Boards.

Research involving human and animal participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Consolidated Guideline, the applicable local laws and regulatory requirements of the countries in which the trial was conducted, and with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The findings of this study were reported in accordance with the CONSORT PRO guidelines for reporting patient-reported outcomes in randomized-controlled trials

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment in the trial.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jamieson, C., Canuso, C.M., Ionescu, D.F. et al. Effects of esketamine on patient-reported outcomes in major depressive disorder with active suicidal ideation and intent: a pooled analysis of two randomized phase 3 trials (ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II). Qual Life Res 32, 3053–3061 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03451-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03451-9