Abstract

Purpose

Self-Reporting using traditional text-based Quality-of-Life (QoL) instruments can be difficult for people living with sensory impairments, communication challenges or changes to their cognitive capacity. Adapted communication techniques, such as Easy-Read techniques, or use of pictures could remove barriers to participation for a wide range of people. This review aimed to identify published studies reporting adapted communication approaches for measuring QoL, the methodology used in their development and validation among adult populations.

Methods

A scoping review of the literature using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews checklist was undertaken.

Results

The initial search strategy identified 13,275 articles for screening, with 264 articles identified for full text review. Of these 243 articles were excluded resulting in 21 studies for inclusion. The majority focused on the development of an instrument (12 studies) or a combination of development with some aspect of validation or psychometric testing (7 studies). Nineteen different instruments were identified by the review, thirteen were developed from previously developed generic or condition-specific quality of life instruments, predominantly aphasia (7 studies) and disability (4 studies). Most modified instruments included adaptations to both the original questions, as well as the response categories.

Conclusions

Studies identified in this scoping review demonstrate that several methods have been successfully applied e.g. with people living with aphasia post-stroke and people living with a disability, which potentially could be adapted for application with more diverse populations. A cohesive and interdisciplinary approach to the development and validation of communication accessible versions of QOL instruments, is needed to support widespread application, thereby reducing reliance on proxy assessors and promoting self-assessment of QOL across multiple consumer groups and sectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

For decades, there has been broad agreement among researchers, health professionals, policy makers and administrators regarding the importance of quality assessment across health and social care systems [1,2,3]. Despite this, there is still no single agreed ‘gold standard’ approach for measuring quality of care. Of the quality of care assessment models and frameworks that are available, the majority include some component of measuring the outcomes of care provided from the perspectives of care recipients themselves [1, 4]. In practice, clinical outcomes (e.g. physiologic markers, mortality or measures of morbidity) have taken the lead as the predominant approach for measuring care outcomes. Such indicators have come under criticism for potential difficulty in their interpretation and lack of meaning to the recipients of care themselves [1]. Additionally, clinical outcomes do not necessarily maintain their meaning and significance across multiple clinical populations. For example, weight loss among people experiencing overweight or obesity-related health conditions may be viewed positively. By comparison, weight loss among frail elderly people would be considered a poor outcome [5]. These challenges, along with the momentum gained from the social movement for involving patients and consumers in planning, managing and evaluating the health and social care they receive, has led to the rise of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) focused on quality of life (QOL) [6].

QOL is one of the most highly utilised PROMs in health research [7]. The maximisation of QOL for patients is acknowledged as the ultimate aim of health and social care [8]. By definition the measurement of QOL is subjective, incorporating the person’s own judgement of their current health and wellbeing in comparison with their expectations for those domains of their lives [9]. Increasingly there have been calls to include QOL as a key quality indicator across both health and social care settings [10]. Presently, a wealth of validated QOL instruments are available for application across a range of different health conditions and settings including generic QOL instruments (such as the EQ-5D-5L or WHOQOL suite of instruments) [7] and condition-specific instruments (for example the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) or the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD)) [7].

While instruments differ in composition, length and complexity, generally they take the form of text-based multiple-choice descriptive systems, requiring reading comprehension and written expression skills to complete. The vast majority of the commonly used instruments are not inclusive of people with diverse communication needs, low literacy or perceptual or cognitive difficulties [11]. Consequently, people with diverse communication needs are often excluded from QOL and outcomes research despite this population comprising a relatively large proportion of those utilising health and social care services [12,13,14]. The World Health Organization estimates over 1 billion people, equivalent to over 15% of the world’s population, live with a physical, sensory, intellectual or mental health impairment which impacts their daily lives [15]. Additionally, on average 20% of the population in OECD countries is either illiterate or has very low literacy skills, impacting on their ability to engage with institutional processes and health information in a written form [16]. The majority of older people receiving aged care services in Australia have some form of cognitive impairment or dementia [17, 18]. Thus, individuals who may find it difficult or impossible to complete traditional text-based PROMs are relatively common among those seeking and using health and social care services. In these settings, proxy assessment of QOL by family members or care providers is often used as the default option [19]. However, it is now acknowledged that proxy respondents are not a direct replacement for self-report of PROMs, due to evidence of systematic differences in the way that proxy assessors respond to questions about the QOL of the person compared to the person themselves [20, 21]. Empirical comparison studies incorporating self and proxy assessment generally find poor to moderate levels of agreement, especially for less easily observable psychosocial focused QOL domains as opposed to physical QOL domains. Generally, for populations of older people it has been found that overall QOL scores (either raw scores or scores converted into utilities) reported by proxy are lower than those reported by older people themselves, and that the difference in scores tends to increase over time [20]. These factors lead to a significant gap in our understanding and consequently our ability to provide high quality care services meeting the needs of the diverse population accessing health and social care services [12, 14, 22]. Presently the voices of large proportions of those accessing services (and particularly vulnerable to having poor QOL e.g. older adults with cognitive impairment and dementia, adults with intellectual impairments and/or sensory difficulties) are not being heard as we do not have appropriate communication accessible QOL instruments to facilitate self-reporting of QOL for quality assessment and evaluation in these populations [10].

Accessible communication techniques include, but are not limited to, pictures, pictograms, easy read or easy-English approaches, or modified layout or presentation of information. It is often assumed that people with communication difficulties, disability, or dementia are unable to speak for themselves [14, 23,24,25]. It is increasingly being recognised that such a diagnosis should not exclude a person from having the opportunity to fully contribute to evaluating the care they receive [26,27,28]. The onus is on the research community to develop better methods to facilitate the maximal inclusion of people who experience a range of cognitive and communication difficulties in self-assessment of their own QOL wherever possible. It has been identified that people with mild or moderate dementia can provide reliable answers on QOL instruments providing that the methods used to assess QOL support their communication needs [29]. Research has shown that adapted communication approaches, such as easy-read techniques, or visual representations of concepts can be successfully applied with groups including people living with intellectual disability, post-stroke aphasia, or culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background to support or replace written communication methods [30,31,32]. However, the extent to which these approaches have been successfully applied in existing QOL instruments is currently unknown.

Therefore, the aim of this review was to identify and describe existing QOL instruments which have used an adapted communication approach for use with adults. A secondary aim was to report the methods used in the development and validation of these instruments.

Methods

A scoping review methodology was undertaken according to PRISMA extension guidelines [33, 34]. The protocol was prospectively registered with the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/27RGS).

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed in consultation with an academic librarian for databases including Medline, PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, Emcare, Informit, PsycINFO, REHABDATA, Web of Science, Health and Social Science Instruments and Google Scholar. Searches were conducted including results up until November 2022 and no date limit was applied. Both subject heading and keyword searches were used where possible. Example search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Eligibility criteria

Studies describing the development or validation of a QOL instrument including a significant component of accessible communication techniques with a focus on visual and/or an easy-read techniques to present the key information were included. Accessible communication techniques include, but are not limited to, pictures, pictograms, easy-read or easy-English approaches, or modified layout or presentation of information. We defined a significant component of accessible communication techniques as including modifications to two or more aspects of the instrument e.g. modification to the items of the instrument, or the response categories. Both generic and disease-specific instruments were eligible for inclusion. Studies reported in a language other than English and conference abstracts were excluded. Review articles were excluded but were hand searched for relevant articles. Studies where the target audience of the instrument, or a significant proportion of the sample (i.e. over 50%), were children or adolescents aged less than 18 years were also excluded. Children or adolescents may also benefit from adapted accessible communication versions of PROMs. However,their communication needs, brain development and cognitive processing are functionally and structurally different to those of adults, and potentially therefore we their needs could be quite different to that of an adult population. Therefore, we chose to focus on adult populations (aged 18 years and above) for this review.

Procedure

Citations were extracted from the electronic databases and imported into the Covidence online platform (https://www.covidence.org/). After duplicates had been removed, two independent reviewers completed two rounds of screening. First, titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria and articles not meeting the criteria were excluded. For the second stage of screening, the full text of the remaining articles were sourced, and reviewed against the eligibility criteria, again by two independent reviewers. Articles which did not meet the criteria were excluded. Any disagreements were resolved by a third independent reviewer. Reference lists of included studies were screened forwards and backwards to identify further eligible studies. The full text of the articles which met the selection criteria were then moved to the next stage of the review, data extraction.

Data extraction

A customised data extraction template was prepared, and extraction was performed independently by two reviewers. The following information was extracted from the papers for inclusion in this scoping review: author(s), year, publication details, country, study focus, population targeted, sample size and composition, QOL instrument included, and any use of accessible communication methods used in the instrument either for the items themselves, or the possible responses. Furthermore, the methods used in the development or adaptation of the instrument were extracted, including, for example, expressed use framework or disciplinary approaches, literature review or expert opinion, working groups incorporating consumers or their advocates, use of picture banks or artists, and focus groups or cognitive interviews. The extent and quality of the psychometric and validity testing of the instrument identified was extracted and categorised using the approach applied by Khadka et al. [35] and Pesudovs et al. [36] adapted from the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Status Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) (see Supplementary Information Table 2) [37]. A narrative synthesis was performed in line with the scoping review aims.

Results

Search results

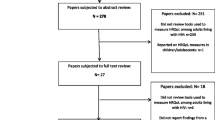

A PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) presents the systematic search results, including the identification, screening and exclusion and inclusion of identified studies. A total of 23,178 studies were retrieved from the search of electronic databases. Following removal of duplicates, 13,275 titles and abstracts were screened, with 13,044 excluded. 267 full text papers were then screened, with 246 of these excluded. The most common exclusion reasons were the instrument having no visual components or not reporting the development or validation of a QOL instrument (for example where the instrument was applied in a clinical trial) (n = 185). A total of 21 studies were included in the scoping review (see Additional file for a detailed summary of included studies) [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 provides the overall summary of the 21 included studies. The majority were conducted in Europe (six studies), the United Kingdom (UK) (five studies), or Canada (five studies). A smaller number were conducted in the United States (US), Asia, Oceania and Africa. The earliest published study was from 2001, with the majority published from 2010 onwards. Twelve studies reported on the development of the instrument only, while seven reported a combination of development of the instrument and tests of its psychometric properties and validity. Two studies focused on the validation of the instrument only.

Overall, nineteen different QOL instruments were identified in the studies. Thirteen were adapted from a range of previously developed instruments. This included instruments representing adaptations from existing widely applied generic QOL instruments, such as the Adult Social Care Outcomes tool (ASCOT-SCT4) [62], WHOQOL-BREF [63], 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) [64], EQ-5D 3-level and 5-level versions [65, 66], Personal Wellbeing Index [67], and Nottingham Health Profile [68]. Some instruments were adapted from stroke specific QOL instruments, such as the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39) [69], Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL) [49] and Assessment for Living with Aphasia (ALA) [70]. Other instruments represented adaptations from less well known/widely applied QOL instruments (for example the Personal Outcome Scale [71], Aachen Life Quality Inventory [72], and the Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP) [65] among others. Four studies reported on communication accessible QOL instruments that were designed from first principles.

As described in Table 1, the largest proportion of the identified studies focused on people with aphasia specifically (seven studies) [38, 43, 46, 49, 53, 58, 61] and people living with a disability more broadly (generally people living with intellectual disability)(four studies) [41, 45, 57, 60]. Another three studies were focused on the general population [42, 59, 73], and two studies were focused on culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations [44, 47]. One study focused on both CALD population and general population [39]. Two other studies focused on people with severe mental health conditions [40, 55], one study focused on older people with cognitive impairment [56], and one study focused on people living with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease [51]. Sample sizes ranged from N = 38, generally for qualitative studies or development processes, to N = 672 for larger scale validation studies. Two studies did not focus on reporting the results of an individual development or validation study, but rather focused on presenting a modified instrument or an overview of the methods used in its development [41, 46].

Methods of development

The methods used in the development of the studies are summarised in Table 2. Thirteen studies (61.9%) included consumers or patients as part of the process of development of the instruments beyond inclusion as survey participants, including: six studies (28.6%)which included consumers as part of focus groups or cognitive interviews to determine the suitability of modifications to items or to develop pictures [39, 44, 52, 53, 56, 59], seven studies (33.3%) which included consumers as part of working groups; and two studies (9.5%) which included consumers as part of focus groups or cognitive interviews as well as in working groups [40, 41, 49, 57, 58, 60, 61]. Four studies (19.05%) indicated that they had included consumers in piloting the questionnaire prior to large scale validation studies [39, 46, 55, 58].

Several approaches were used for the development of the modified instruments. Three studies (14.29%) described using theoretical frameworks for their modification of the instrument [41, 58, 61], usually drawn from the speech-language therapy literature, such as ‘Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia’, or ‘Aphasia-Friendly conventions’, or a ‘Total Communication Approach’ [74,75,76]. Eleven studies (52.38%) used an iterative process (i.e. where the instrument was developed in multiple stages with revisions made in response to feedback, which was then provided for more feedback, with more revisions made and so on. For example, initial pictorial representations were created, and these were then modified via successive rounds of feedback from consumers, family member carers and/or clinicians to further enhance and refine the pictures [39,40,41, 44, 45, 56,57,58,59,60,61].Twelve studies (57.13%) used focus groups or cognitive interviews to determine clarity, intelligibility, and appropriateness of modifications to instrument’s items commonly using structured approaches such as ‘think-aloud’ or ‘verbal probing’ methods [39,40,41, 44,45,46, 49, 56,57,58, 60, 61]. Use of literature review and expert opinion was widely used for the instruments developed for people with aphasia specifically [46, 49, 50, 53, 58, 61], and people living with another disability (such as an intellectual disability) [41, 45]. Two studies (9.52%) used existing banks of images used for communication aids (for example with people living with aphasia) as a source of suitable pictures [39, 61]. Seven studies (33.33%) developed their own images for use with an artist of other professional [43, 48, 55, 57, 59,60,61].

Modification of instrument

This review identified a range of communication accessible modifications made to QOL instruments, including removal, or alteration of instrument items, use of pictures, images or picograms, editing of language following easy-read principles, modification of layout or presentation of items, or multimodal systems (incorporating audio or video elements in addition to text) to maximise consumers’ understanding of the items. All instruments included in this review modified the question items (Table 3), and all but one [53] modified the presentation of the possible response categories (Table 4). In terms of modifications to the items, the use of pictures to communicate content was widespread, with fourteen studies using line drawings or cartoons to represent or replace text describing the QOL domain [39,40,41, 43, 45, 47, 48, 51, 55,56,57].Use of black and white line drawings was common, perhaps as these allow easy and inexpensive high quality replication of the instrument via printing or photocopy. Modifications to the text of the questionnaires included: using short verbal phrases or simplifying wording; introducing additional explanations or lead-in questions; using bold text to highlight key words; or changing the formatting of the question items for example changing text size, increasing size of blank space, or presenting one question per page [39,40,41, 44, 46,47,48,49, 53, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

Use of pictograms to replace the potential response categories of the instrument was widespread, with all but three studies [46, 49, 50] using pictograms either alongside text or to replace text for the response categories. Use of Smiley faces (for example a frowning face for a poor level of QOL, a happy face for a good level of QOL) was common [39, 42, 43, 53, 59], but alternatives were investigated such as use of hands showing ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ [43], arrows or circles of increasing size [39], or cups of water/buckets of varying from empty to full of liquid [41]. An alternative approach was to use more detailed pictures relating to the expression of response levels, for example a picture of someone bed bound compared to someone walking with a walking frame, and someone walking independently to indicate different levels of mobility [39, 48, 56].

Instrument validation

The quality and extent of validation undertaken for the identified instruments varied significantly (see Table 5). Generally, the methods for the development of the instrument were of high quality, with the intended population included, and widespread use of qualitative research or literature review and expert opinion to select items relevant to the target population. Validity and reliability testing for the instruments was notably less extensive. Thirteen of the studies did not include testing of convergent validity [39, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47, 49, 51, 56, 59,60,61], four included some testing of discriminant validity [48, 49, 55, 58] and only one included assessment of predictive or known group validity [46]. Seven studies included an assessment of reliability such as test-re-test agreement, interobserver or mode agreement, or [45, 46, 50, 51, 53, 58, 59].

Discussion

This review identified 21 QOL instruments which included an accessible communication component. Although we included QOL instruments developed for any population aged over 18 years, this review identified that the majority had been developed for use with people living with post-stroke aphasia or people living with a disability more generally (usually people living with an intellectual disability). The use of accessible communication methods in QOL instruments has been an area of focus more recently, with the majority of studies published from 2017 onwards. This relatively recent focus corresponds with the increasing emphasis in policy and practice for inclusion of consumer voices in assessing care quality and in health research more generally [15, 77,78,79].

As researchers have sought ways to gain the authentic involvement of people receiving health and social care services including in the evaluation of the quality of care, the diverse communication needs within populations accessing health and social care has become more apparent [80, 81]. Subsequently, the deficiencies of the ‘one-size fits all’ approach of text-based multiple-choice questionnaires, which forms most of the available PROMs, have become clearer. Researchers and practitioners in the sector have, therefore, begun to seek and develop solutions. However, the research in this area remains in its infancy. Approaches so far have generally focused on developing and validating an instrument for use with a targeted population group, for example, people living with post-stroke aphasia specifically or people living with a disability more generally.

In practice, for the application of QOL as a key quality indicator in large scale system-wide quality assessment and evaluation, communication accessible versions of QOL instruments will need to be applied consistently across diverse populations. As an example, the population using long-term care services may include older people with a range of cognitive abilities, a range of communication difficulties, and people from diverse CALD backgrounds. There is a need for rigorous development and testing processes (including qualitative and quantitative approaches) to ensure the validity of communication accessible QOL instruments by the PROM research community that can be applied with confidence across multiple diverse population groups.

Positively, there are examples of promising approaches which may form the foundations for larger scale research programs to develop communication accessible QOL instruments. There is strong evidence of the successful involvement of consumers and end users, informal family carers, care professionals and stakeholders in the development of such instruments. Successful approaches have included iterative methods where steering groups have reviewed existing QOL instruments and recommended adaptations, which were then trialled and tested in the field. Other structured approaches to involving consumers in the development process include use of qualitative think-aloud, cognitive interviewing, ‘staggered reveal’ or verbal probing approaches used as part of focus groups or in-depth individual interviews. These methods have been used successfully with people with aphasia [46, 49, 58, 61], with an intellectual disability [41, 45, 57, 60] with a mental health condition [40], people with a CALD background [44] as well as older people [56] and the general population [39], providing evidence of their broad applicability across multiple populations and communication needs.

Commonly applied modifications to existing QOL instruments have included use of pictures simplification of text, formatting changes, and use of pictograms to support responses. To date, the use of technology to facilitate the completion of QOL instruments by consumers with communication challenges has been limited. Only one study by Hahn et al., 2004 [47] developed a talking computer touchscreen with cancer patients with low literacy. With the recent prolific increase in digital capability and capacity in Australia and internationally, this is an area which may hold significant promise for the future, for example through the adaption of QOL instruments for presentation on a tablet or smart phone using video, audio or animated enhancements to support understanding and completion.

To date, no communication accessible QOL instruments have undergone extensive development and validation. Of the 21 studies identified in this review focusing on 19 different instruments, few reported validity testing of new or adapted QOL instruments. Notably, only seven studies included some assessment of the reliability of the instrument in its communication accessible form such as test-re-test agreement, interobserver or intermode agreement. Detailed evaluation of the validity of these instruments is critical. Although some have been based on instruments which have been widely used and validated previously (such as the EQ-5D-5L, WHOQOL-100 and WHOQOL-BREF, or SF-36), any modifications made to the instrument would necessitate a new validation of the modified version [6, 69]. A particularly important criterion to assess is interobserver or intermode agreement for communication accessible instruments [82]. It is likely that in any large scale application in health and/or social care systems, a proportion of the population would need to access a communication accessible version in order to facilitate self-completion. It will be important to ensure there are no systematic biases in the results obtained from different versions of the same QOL instrument, to ensure QOL assessment and reporting is valid and reliable across population groups [82,83,84].

Conclusions

This review has identified a number of studies which have reported on the development and/or validation of communication accessible versions of QOL instruments. Studies identified in this scoping review demonstrate that several methods have been successfully applied e.g. with people living with aphasia post-stroke and people living with an intellectual disability, which potentially could be adapted for application with more diverse populations. A cohesive and interdisciplinary approach to the development and validation of communication accessible versions of QOL instruments, is needed to support widespread application, thereby reducing reliance on proxy assessors and promoting self-assessment of QOL across multiple consumer groups and sectors.

References

Castle, N. G., & Ferguson, J. C. (2010). What is nursing home quality and how is it measured? The Gerontologist, 50(4), 426–442.

Burke, R. E., & Werner, R. M. (2019). Quality measurement and nursing homes: Measuring what matters. BMJ Quality and Safety, 28(7), 520–523.

Round, J., Sampson, E. L., & Jones, L. (2014). A framework for understanding quality of life in individuals without capacity. Quality of Life Research, 23(2), 477–484.

Cleland, J., Hutchinson, C., Khadka, J., Milte, R., & Ratcliffe, J. (2021). What defines quality of care for older people in aged care? A comprehensive literature review. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 21(9), 765–778.

Milte, R., & Crotty, M. (2014). Musculoskeletal health, frailty and functional decline. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 28(3), 395–410.

Crawford, M. J., Rutter, D., Manley, C., Weaver, T., Bhui, K., Fulop, N., & Tyrer, P. (2002). Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ, 325(7375), 1263.

Brazier, J., Ratcliffe, J., Salomon, J. A., & Tsuchiya, A. (2017). Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization.

Carr, A. J., Gibson, B., & Robinson, P. G. (2001). Measuring quality of life: Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? British Medical Journal, 322(7296), 1240–1243.

Addington-Hall, J., & Kalra, L. (2001). Who should measure quality of life? British Medical Journal, 322(7299), 1417–1420.

Siette, J., Knaggs, G. T., Zurynski, Y., Ratcliffe, J., Dodds, L., & Westbrook, J. (2021). Systematic review of 29 self-report instruments for assessing quality of life in older adults receiving aged care services. British Medical Journal Open, 11(11), e050892.

Stineman, M. G., & Musick, D. W. (2001). Protection of human subjects with disability: Guidelines for research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82, S9–S14.

Shepherd, V., Wood, F., Griffith, R., Sheehan, M., & Hood, K. (2019). Protection by exclusion? The (lack of) inclusion of adults who lack capacity to consent to research in clinical trials in the UK. Trials, 20(1), 474.

Taylor, J. S., DeMers, S. M., Vig, E. K., & Borson, S. (2012). The disappearing subject: Exclusion of people with cognitive impairment and dementia from geriatrics research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(3), 413–419.

World Health Organization and World Bank. (2011). World report on disability. World Health Organization.

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2019). Skills matter: Additional results from the survey of adult skills. OECD Publishing.

Matthews, F. E., Arthur, A., Barnes, L. E., Bond, J., Jagger, C., Robinson, L., & Brayne, C. (2013). A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: Results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Lancet, 382(9902), 1405–1412.

Carter, D. (2015). Dementia & homecare: Driving quality & innovation. United Kingdom Homecare Association.

Ratcliffe, J., Laver, K., Couzner, L., & Crotty, M. (2012). Health economics and geriatrics: Challenges and opportunities. In C. S. Atwood (Ed.), geriatrics (pp. 209–234). InTech.

Hutchinson, C., Worley, A., Khadka, J., Milte, R., Cleland, J., & Ratcliffe, J. (2022). Do we agree or disagree? A systematic review of the application of preference-based instruments in self and proxy reporting of quality of life in older people. Social Science and Medicine, 305, 115046.

Stancliffe, R. J. (2000). Proxy respondents and quality of life. Evaluation and Program Planning, 23(1), 89–93.

Witham, M. D., Anderson, E., Carroll, C., Dark, P. M., Down, K., Hall, A. S., Knee, J., Maier, R. H., Mountain, G. A., Nestor, G., Oliva, L., Prowse, S. R., Tortice, A., Wason, J., Rochester, L., Group, I. W. (2020). Developing a roadmap to improve trial delivery for under-served groups: Results from a UK multi-stakeholder process. Trials, 21(1), 694.

Kitchin, R. (2000). The Researched Opinions on Research: Disabled people and disability research. Disability & Society, 15(1), 25–47.

Bigby, C., Frawley, P., & Ramcharan, P. (2014). Conceptualizing inclusive research with people with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(1), 3–12.

Shiggins, C., Ryan, B., O’Halloran, R., Power, E., Bernhardt, J., Lindley, R. I., McGurk, G., Hankey, G. J., & Rose, M. L. (2022). Towards the consistent inclusion of people with aphasia in stroke research irrespective of discipline. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 103(11), 2256–2263.

Alzheimer Europe. (2011). The ethics of dementia research. Alzheimer Europe.

Alzheimer’s Australia. (2013). Quality of residential aged care: The consumer perspective. Alzheimer’s Australia.

Hotter, B., Ulm, L., Hoffmann, S., Katan, M., Montaner, J., Bustamante, A., & Meisel, A. (2017). Selection bias in clinical stroke trials depending on ability to consent. BMC Neurology, 17(1), 206.

Trigg, R., Jones, R. W., & Skevington, S. M. (2007). Can people with mild to moderate dementia provide reliable answers about their quality of life? Age and Ageing, 36(6), 663–669.

Chinn, D., & Homeyard, C. (2017). Easy read and accessible information for people with intellectual disabilities: Is it worth it? A meta-narrative literature review. Health expectations : An international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 20(6), 1189–1200.

Clunne, S. J., Ryan, B. J., Hill, A. J., Brandenburg, C., & Kneebone, I. (2018). Accessibility and applicability of currently available e-mental health programs for depression for people with poststroke aphasia: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(12), e291.

Grobler, S., Casey, S., & Farrell, E. (2022). Making information accessible for people with aphasia in healthcare. Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation, 21(1), 16–18.

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143.

Khadka, J., McAlinden, C., & Pesudovs, K. (2013). Quality assessment of ophthalmic questionnaires: Review and recommendations. Optometry and Vision Science, 90(8), 720–744.

Pesudovs, K., Burr, J. M., Harley, C., & Elliott, D. B. (2007). The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optometry and Vision Science, 84(8), 663–674.

Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Knol, D. L., Stratford, P. W., Alonso, J., Patrick, D. L., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. W. (2010). The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(1), 22.

Bose, A., McHugh, T., Schollenberger, H., & Buchanan, L. (2009). Measuring quality of life in aphasia: Results from two scales. Aphasiology, 23(7–8), 797–808.

Brzoska, P., Erdsiek, F., Aksakal, T., Mader, M., Olcer, S., Idris, M., Altinok, K., Wahidie, D., Padberg, D., & Yilmaz-Aslan, Y. (2022). Pictorial assessment of health-related quality of life. Development and pre-test of the PictoQOL Questionnaire. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1620.

Buitenweg, D. C., Bongers, I. L., van de Mheen, D., van Oers, H. A. M., & Van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2018). Worth a thousand words? Visual concept mapping of the quality of life of people with severe mental health problems. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 27(3), 1721.

Clark, L., Pett, M. A., Cardell, E. M., Guo, J. W., & Johnson, E. (2017). Developing a health-related quality-of-life measure for people with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55(3), 140–153.

Day, A. (2004). The development of the MYMOP pictorial version. Acupuncture in Medicine, 22(2), 68–71.

Engell, B., Hütter, B. O., Willmes, K., & Huber, W. (2003). Quality of life in aphasia: Validation of a pictorial self-rating procedure. Aphasiology, 17(4), 383–396.

Erdsiek, F., Aksakal, T., Dyck, M., Padberg, D., Yilmaz-Aslan, Y., & Brzoska, P. (2020). Language barriers in HRQOL assessment: Development of a picture-based questionnaire (PictoQOL). European Journal of Public Health, 30(Supplement 5), v806.

Fellinger, J., Dall, M., Gerich, J., Fellinger, M., Schossleitner, K., Barbaresi, W. J., & Holzinger, D. (2021). Is it feasible to assess self-reported quality of life in individuals who are deaf and have intellectual disabilities? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(10), 1881–1890.

Guo, Y. E., Togher, L., Power, E., & Heard, R. (2016). Validation of the assessment of living with aphasia in Singapore. Aphasiology, 31(9), 981–998.

Hahn, E. A., Cella, D., Dobrez, D., Shiomoto, G., Marcus, E., Taylor, S. G., Vohra, M., Chang, C. H., Wright, B. D., Linacre, J. M., Weiss, B. D., Valenzuela, V., Chiang, H. L., & Webster, K. (2004). The talking touchscreen: A new approach to outcomes assessment in low literacy. Psycho-Oncology, 13(2), 86–95.

Hardt, J. (2015). A new questionnaire for measuring quality of life—The Stark QoL. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13(1), 1–7.

Hilari, K., & Byng, S. (2001). Measuring quality of life in people with aphasia: The Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 36(Suppl), 86–91.

Hilari, K., Byng, S., Lamping, D. L., & Smith, S. C. (2003). Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39): Evaluation of acceptability, reliability, and validity. Stroke, 34(8), 1944–1950.

Holtmann, G., Chassany, O., Devault, K. R., Schmitt, H., Gebauer, U., Doerfler, H., & Malagelada, J. R. (2009). International validation of a health-related quality of life questionnaire in patients with erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 29(6), 615–625.

Kagan, A., Simmons-Mackie, N., Rowland, A., Huijbregts, M., Shumway, E., McEwen, S., Threats, T., & Sharp, S. (2008). Counting what counts: A framework for capturing real-life outcomes of aphasia intervention. Aphasiology, 22(3), 258–280.

Long, A. F., Hesketh, A., Paszek, G., Booth, M., & Bowen, A. (2008). Development of a reliable self-report outcome measure for pragmatic trials of communication therapy following stroke: The Communication Outcome after Stroke (COAST) scale. Clinical Rehabilitation, 22(12), 1083–1094.

Palmer, S. (2004). Hōmai te Waiora ki Ahau: A tool for the measurement of wellbeing among Māori—The evidence of construct validity. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 33(2), 50–58.

Phattharayuttawat, S., Ngamthipwatthana, T., & Pitiyawaranun, B. (2005). The development of the Pictorial Thai Quality of Life. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, 88(11), 1605–1618.

Phillipson, L., Smith, L., Caiels, J., Towers, A. M., & Jenkins, S. (2019). A cohesive research approach to assess care-related quality of life: lessons learned from adapting an easy read survey with older service users with cognitive impairment. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1609406919854961.

Rand, S., Towers, A. M., Razik, K., Turnpenny, A., Bradshaw, J., Caiels, J., & Smith, N. (2020). Feasibility, factor structure and construct validity of the easy-read Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT-ER)*. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 45(2), 119–132.

Simmons-Mackie, N., Kagan, A., Victor, J. C., Carling-Rowland, A., Mok, A., Hoch, J. S., Huijbregts, M., & Streiner, D. L. (2014). The assessment for living with aphasia: Reliability and construct validity. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(1), 82–94.

Stothers, B., & Macnab, A. J. (2019). Creation and Initial validation of a picture-based version of the limitations of activity domain of the SF-36. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(10), 937–941.

Turnpenny, A., Caiels, J., Whelton, B., Richardson, L., Beadle-Brown, J., Crowther, T., Forder, J., Apps, J., & Rand, S. (2018). Developing an Easy Read Version of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT). Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), e36–e48.

Whitehurst, D. G. T., Latimer, N. R., Kagan, A., Palmer, R., Simmons-Mackie, N., Victor, J. C., & Hoch, J. S. (2018). Developing Accessible, pictorial versions of health-related quality-of-life instruments suitable for economic evaluation: A report of preliminary studies conducted in Canada and the United Kingdom. PharmacoEconomics—Open, 2(3), 225–231.

Malley, J. N., Towers, A. M., Netten, A. P., Brazier, J. E., Forder, J. E., & Flynn, T. (2012). An assessment of the construct validity of the ASCOT measure of social care-related quality of life with older people. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10(21), 1–14.

World Health Organization. (1996). WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: Field trial version, December 1996. World Health Organization.

Brazier, J. E., Harper, R., Jones, N. M., O’Cathain, A., Thomas, K. J., Usherwood, T., & Westlake, L. (1992). Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: New outcome measure for primary care. BMJ, 305(6846), 160–164.

The EuroQol Group. (1990). EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy, 16(3), 199–208.

Janssen, M. F., Birnie, E., Haagsma, J. A., & Bonsel, G. J. (2008). Comparing the standard EQ-5D three-level system with a five-level version. Value in Health, 11(2), 275–284.

International Wellbeing Group. (2013). Personal wellbeing index. Deakin University, Melbourne.

Hunt, S. M., McKenna, S. P., McEwen, J., Backett, E. M., Williams, J., & Papp, E. (1980). A quantitative approach to perceived health status: A validation study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 34(4), 281–286.

Hütter, B. O., & Würtemberger, G. (1997). Reliability and validity of the German version of the sickness impact profile in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychology & Health, 12(2), 149–159.

Kagan, A., Simmons-Mackie, N., Victor, J. C., Carling-Rowland, A., Hoch, J., & Huijbregts, M. (2013). Assessment for living with aphasia (ALA). Toronto: Aphasia Institute.

Paterson, C. (1996). Measuring outcomes in primary care: A patient generated measure, MYMOP, compared with the SF-36 health survey. BMJ, 312(7037), 1016–1020.

van Loon, J., van Hove, G., Schalock, R., & Claes, C. (2008). Personal Outcomes Scale (POS): A scale to assess an individual’s quality of life. Stichting Arduin.

Hardt, J. (2015). A new questionnaire for measuring quality of life—The Stark QoL. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13(1), 174.

Kagan, A. (1998). Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: Methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology, 12(9), 816–830.

Rose, T. A., Worrall, L. E., Hickson, L. M., & Hoffmann, T. C. (2011). Aphasia friendly written health information: Content and design characteristics. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(4), 335–347.

Lawson, R., & Fawcus, M. (1999). The Aphasia Therapy File. Increasing effective communication using a total communication approach (1st ed.). ImprintPsychology Press.

Edwards, H., Courtney, M., & Spencer, L. (2003). Consumer expectations of residential aged care: Reflections on the literature. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9(2), 70–77.

World Health Organization. (2012). Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse.

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2019). Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019). 2018—Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). 44300—Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2015 Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

McKenna, S. P. (2011). Measuring patient-reported outcomes: Moving beyond misplaced common sense to hard science. BMC medicine, 9, 86–86.

Puhan, M. A., Soesilo, I., Guyatt, G. H., & Schunemann, H. J. (2006). Combining scores from different patient reported outcome measures in meta-analyses: When is it justified? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 94.

Johnston, B., Patrick, D., Devji, T., Maxwell, L., Bingham III, C., Beaton, D., Boers, M., Briel, M., Busse, J., Carrasco-Labra, A., Christensen, R., da Costa, B., El Dib, R., Lyddiatt, A., Ostelo, R., Shea, B., Singh, J., Terwee, C., Williamson, P., Gagnier, J., Tugwell, P., & Guyatt, G. (2022). Chapter 18: Patient-reported outcomes. In T. J. Higgins JPT, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (Ed.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Vol. version 6.3 (updated February 2022)): Cochrane

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This work was supported by a Flinders University Research Support for Early and Mid-Career Researchers Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study protocol was developed by Dr RM and all other authors reviewed and provided comments. DJ performed the searches of databases and collated the results. Screening of the studies was performed by Dr RM, DJ, KL, Dr JT and Dr JM. Data Extraction and drafting of the manuscript was performed by Dr RMand DJ. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Milte, R., Jemere, D., Lay, K. et al. A scoping review of the use of visual tools and adapted easy-read approaches in Quality-of-Life instruments for adults. Qual Life Res 32, 3291–3308 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03450-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03450-w