Abstract

Purpose

There are limited data on the impact of caregiving for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) on the caregiver. We aimed to identify the demographic characteristics of these caregivers, the caregiving activities they perform and how caregiving burden impacts their work productivity and overall activity.

Methods

This cross-sectional study collected data from caregivers of patients with MPM across France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom January-June 2019. Caregiver demographics, daily caregiving tasks and the impact of caregiving on physical health was collected via questionnaire. The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) was used to assess caregiver burden and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI) assessed impairment at work and during daily activities. Analyses were descriptive.

Results

Overall, 291 caregivers provided data. Caregivers were mostly female (83%), living with the patient (82%) and their partner/spouse (71%). Caregivers provided over five hours of daily emotional/physical support to patients. ZBI scores indicated 74% of caregivers were at risk of developing depression. Employed caregivers had missed 12% of work in the past seven days, with considerable presenteeism (25%) and overall work impairment (33%) observed. Overall, the mean activity impairment was 40%.

Conclusion

Caregivers provide essential care for those with MPM. We show caregiving for patients with MPM involves a range of burdensome tasks that impact caregivers’ emotional health and work reflected in ZBI and WPAI scores. Innovations in the management of MPM must account for how caregivers may be impacted and can be supported to carry out this important role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a tumour that develops in the mesothelial surfaces of the pleura. It is associated with exposure to asbestos, with asbestos workers and those residing near asbestos manufacturing plants being at increased risk of developing MPM [1,2,3,4]. MPM has a long latency period of around 40 years, patients are often older males with a mean age of approximately 70 years at diagnosis, a median survival time of 8–14 months from diagnosis, and a 5-year survival rate of 10% [5,6,7,8,9].

MPM is relatively rare with 34,614 new cases reported globally in 2017. Until recently, cases had been rising across most countries; it was only 20–30 years after banning asbestos use that countries like France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK) started to see a decline in cases [10, 11]. Given the long latency, cases are likely to continue to rise in countries slower to enact a complete ban as many countries are yet to reach expected peak death rates [12,13,14].

MPM is highly aggressive [15], with a majority of patients presenting with late-stage unresectable disease that responds poorly to treatment [16, 17]. Previously there was little innovation in successful treatment for over a decade and treatment options remained limited for patients with MPM. More recently, nivolumab and ipilimumab immunotherapy has been approved in the United States (US) [18] and is recommended in the European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines [19]. Patients and their caregivers will experience prolonged periods of treatment (many treatment cycles followed by maintenance therapy) and the burden associated with treatment.

MPM is associated with an overall sense of physical debilitation and poor health, depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment [20]. Given the highly symptomatic and aggressive nature of MPM, many patients require the assistance of caregivers [21]. Caregivers are often spouses, female and over 50 years of age [20, 22]. Due to the rapid progression of MPM and its physical and emotional toll, caregiver burden is likely to be high. However, there are limited data on caregiver burden in MPM and thus it has remained poorly understood.

Caregiver burden has been defined by a multidimensional approach, considering the physical, emotional, psychological, social and financial impacts on caregivers [23, 24]. The limited data on caregiving in MPM has shown that emotional functioning of caregivers is significantly impaired, with caregivers reporting higher levels of personal distress, receiving less support, and feeling less well-informed throughout the process of diagnosis than the patients they care for [20]. In addition, caregivers have poorer physical health than healthy peers and higher rates of depression and intrusive thoughts about death than the patients they care for [25].

In many countries, informal caregiving represents the backbone of the social care delivery system [26], providing an estimated annual economic value of €576 billion in 2016/2017 [27]. Informal caregivers are estimated to make up 10–25% of the total population of caregivers in Europe [28] and provide 80% of long-term care [29]. Therefore, without informal caregivers, societal costs, including health and social care costs would likely be severe. Thus, it is important to understand the burden placed on informal caregivers to ensure they receive the required support. Until recently, support for MPM was based on existing care infrastructures established for lung cancer patients; however, this fails to recognise the different needs in MPM [22]. One study found patients with MPM felt more hopelessness than patients with lung cancer—perhaps owing to fewer successful treatment options in MPM—and many felt anger that their disease resulted from bad workplace practices [30]. Further distress has been linked to delays in MPM diagnoses and uncertain prognoses [22]. These studies highlight how the challenges faced by patients with MPM and their caregivers may differ from patients with lung cancer.

There is a paucity of research on MPM caregiving, with much of the information about caregiver burden being anecdotal [20]. Therefore, there are many gaps in our understanding of caregiver burden in MPM. We aimed to identify the demographic characteristics of caregivers of patients with MPM, the caregiving activities they perform, and which of these were the most troublesome. We also investigated the burden of caregiving, and its impact on the caregivers’ health, work productivity and overall activity. We describe these data stratified by the clinical characteristics of the patients with MPM being cared for to further understand how these characteristics impact the caregiver’s role and associated burden.

Methods

Study design

Data were drawn from a larger multinational survey of physicians, patients with MPM and their caregivers in a real-world setting that included retrospective and cross-sectional data collection [31]. Physicians abstracted retrospective data from their next 5–10 eligible consulting patients’ medical charts. Each patient and any primary caregiver accompanying the patient to a consultation were invited to complete a patient or caregiver questionnaire. Physicians were selected by local data collection agencies. Physicians had to be specialists in oncology or pulmonology, qualified for 5–35 years, personally responsible for the management of patients with unresectable MPM and have consulted with at least five patients with MPM over the past three months. Patients were adults (aged over 18 years), had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of unresectable MPM and were not participating in a clinical trial. Data from patients and physicians on treatment patterns and patient burden have previously been published [31].

Participants

In this report, we focused on caregiver survey data. Caregiver data were collected from 291 caregivers across France, Italy, Spain and the UK between January and June 2019, allowing us to collect caregiver perspectives across a variety of healthcare systems in Europe.

Caregivers eligible for inclusion in the current study were aged 18 years or over and the primary caregiver (spouse, partner, child, other relative or friend) providing informal (unpaid) care for a patient diagnosed with unresectable MPM.

In total, there were 297 patients from the overall survey that had a caregiver recorded within their medical record but no corresponding caregiver self-completion questionnaire (CSC). Whilst exact response rates were not captured, our sample of 291 caregivers suggests a response rate of close to 50%.

Study measures

Each caregiver filled out a CSC. Demographic information was collected including age, sex, living situation (with or not with patient), relationship to patient, employment status and household income.

To identify caregiving tasks undertaken daily, caregivers were given a list of 22 options of daily tasks and asked to select as many as were applicable to them and their top three most troublesome activities.

To measure overall impact on health, caregivers were asked to rate the impact caregiving had on their health with response choices on a 7-point numerical rating scale from 1 = “did not impact my health at all” to 7 = “severely impacted my health”.

The Zarit Burden interview (ZBI) assessed the level of caregiver burden [32] and has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of caregiver burden [33, 34].Validated translations were used. The ZBI is a 22-item questionnaire designed to measure subjective degree of burden on a 5-point scale, for each question caregivers selected from 0 = “never” to 4 = ”almost always”. The ZBI comprises questions that fit into different domains, the scores for each domain are calculated by adding the cumulative scores given for each question in that domain. The domains are burden in the relationship (range = 0–24), emotional well-being (range = 0–28), social and family life (range = 0–16), loss of control over one’s life (range = 0–16), finances (range = 0–4), personal strain (range = 0–48) and role strain (range = 0–24). ZBI total score is the sum of scores and ranges between 0 and 88, with higher scores indicating greater burden [35]. Schreiner et al. identified a statistically valid threshold score of 24 for the ZBI to identify caregivers at risk for depression, whereby caregivers with this score or higher were considered at risk of developing depression [36].

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI) was used to assess caregivers’ impairment at work during the past seven days. WPAI is a validated measure that consists of four scores: absenteeism (work time missed), presenteeism (impairment at work/reduced on-the-job effectiveness), work productivity loss (overall work impairment) and activity impairment (regular activities other than work) [37]. WPAI scores range from 0–100 (expressed as impairment percentages), with higher scores indicating greater impairment. The versions administered had undergone independent translations, harmonization, back-translation, expert review, and review by local language users [38].

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata v16 [39]. Caregivers were stratified by country, age, patients’ current line of treatment, ECOG performance score (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group—higher scores indicate greater difficulty caring for themselves) of the patient and patient MPM subtype.

No formal hypotheses were developed prior to conducting this study and all analyses were descriptive in nature with no statistical comparisons conducted. Missing data were not imputed. The number of observations is reported for each variable. In general, missingness was very low, with no missing data observed for variables related to caregiving activities or the ZBI. Continuous variables were described as means and standard deviations (SD) and categorical variables were described as numbers and percentages.

Results

Demographics

Overall, 291 CSC forms were collected for caregivers of patients with MPM from France (n = 90), Italy (n = 70), Spain (n = 111) and the UK (n = 20). Patient demographics for whom the caregivers in this study provided care are presented in Table 1. The table also includes demographics of patients included in the medical chart abstraction that had a known caregiver that did not complete a CSC (n = 297). The effect size of differences between these cohorts was ≤ 0.2 for all demographic and clinical characteristics.

Caregivers had a mean age of 59 years, 83% were female and 82% were living with the patient they cared for, with 71% being the patient’s spouse/ partner (caregivers that were spouses/ partners had a mean age of 63 years). In total, 36% of caregivers were working alongside their caregiving duties and 38% were retired (Table 2).

Caregiving activities

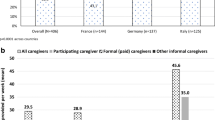

Caregivers spent an average of 5.8 (SD: 6.3) hours of their day providing emotional or physical support; the most frequently reported caregiver task was providing emotional support and encouragement, with 81% of caregivers reporting that the patient required this support daily. The next most common caregiving activities reported were travelling out of home (58%), driving patients to work/ hospital/ appointments (56%) and helping with preparing meals (52%). Figure 1 presents the stratified caregiving activities data. The proportion engaging in these activities daily was generally higher for caregivers of patients receiving second-line (2L) + systemic anti-cancer therapy (SACT) and 2L + best supportive care (BSC), than patients on first-line (1L) SACT or 1L maintenance, those caring for patients with the sarcomatoid subtype of MPM and when caring for patients with ECOG 2 and above.

Top five caregiving activities undertaken daily by caregivers of patients with MPM (% of caregivers completing each task daily). Data are stratified by country, patient current line of treatment, caregiver age, ECOG score and MPM subtype. Best supportive care, BSC; caregiver self-completion form received, CSC; Eastern cooperative oncology group, ECOG—higher scores indicate lower performance status; first-line,1L; maintenance, maint; malignant pleural mesothelioma, MPM; systemic anti-cancer therapy, SACT; second-line, 2L; United Kingdom, UK

Overall, the top five most troublesome caregiving activities reported were: providing patients with emotional support/encouragement (49%), driving the patient to work/hospital/appointments (28%), helping the patient travel out of their home (20%), getting patient dressed/washed (18%) and help with preparing meals (13%).

We found some differences across countries in the perceived burden of different activities, with one in three caregivers in France and Italy reporting that providing emotional support was one of the top three most troublesome tasks compared with two in three caregivers in Spain and the UK (Fig. 2).

Top five most troublesome caregiving activities undertaken daily by caregivers of patients with MPM (% of caregivers selecting each task within their top three most troublesome tasks). Data are stratified by country, patient current line of treatment, caregiver age, ECOG score and MPM subtype. Best supportive care, BSC; caregiver self-completion form received, CSC; Eastern cooperative oncology group, ECOG—higher scores indicate lower performance status; first-line,1L; maintenance, maint; malignant pleural mesothelioma, MPM; systemic anti-cancer therapy, SACT; second-line, 2L; United Kingdom, UK

Caregiver burden (ZBI)

Caregivers’ overall mean (SD) ZBI total score was 34.5 (15.3). Overall, 74% of caregivers had a ZBI score of ≥ 24 (indicating high risk of depression) and the mean total score of all subgroups was ≥ 24. Caregivers of patients with worse performance score (ECOG > 2) or with sarcomatoid MPM reported experiencing higher burden (Fig. 3). Similarly, caregivers of patients at 1L-maintenance and 2L + experienced higher burden than those caring for patients at 1L-SACT.

Mean ZBI-total stratified by country, age, patients’ current treatment, current line of treatment, disease subtype and ECOG performance score. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Best supportive care, BSC; caregiver self-completion form received, CSC; Eastern cooperative oncology group, ECOG—higher scores indicate lower performance status; first-line,1L; maintenance, maint; malignant pleural mesothelioma, MPM; systemic anti-cancer therapy, SACT; second-line, 2L; United Kingdom, UK; Zarit burden interview scale, ZBI

Caregivers of older patients (65 + years) and those with poor performance status (ECOG > 2) reported higher ZBI scores across all domains than caregivers of younger patients (< 65 years) or with better performance status (ECOG < 2). Caregivers of patients with the sarcomatoid subtype of MPM reported higher burden in all domains compared with those caring for patients with other MPM subtypes. Caregivers of patients currently receiving 2L + BSC had lower burden than caregivers of patients currently receiving 1L-maintenance and 2L + SACT treatment (see Supplementary Fig. 1a–g). Although descriptive differences in ZBI total scores were observed between subgroups, these differences were cumulative across subdomains rather than being due to differences in individual domains.

Impact of caregiving on physical health

In total, 75% of caregivers reported that caregiving had impacted their health (Fig. 4). Overall, 63% of caregivers were taking medication to treat a condition that they believed had been brought on or exacerbated due to caregiving.

Impact of MPM on caregiver work and activity

During the seven days prior to data collection, caregivers reported missing approximately 12% of work time, were impaired while working 25% of the time and their overall work impairment was 33%. Overall, the mean degree of activity impairment for caregivers of patients with MPM was 40% (Table 3). Activity impairment was highest for caregivers of patients > 65 years old, caregivers of patients currently receiving 1L maintenance and caregivers of patients with ECOG performance scores > 2 (Fig. 5).

Mean overall activity impairment (WPAI) in caregivers of patients with MPM, stratified by country, age, patients’ current line of treatment, disease subtype and ECOG performance score. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Best supportive care, BSC; caregiver self-completion form received, CSC; Eastern cooperative oncology group, ECOG—higher scores indicate lower performance status; first-line,1L; maintenance, maint; malignant pleural mesothelioma, MPM; systemic anti-cancer therapy, SACT; second-line, 2L; United Kingdom, UK; work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire, WPAI

Discussion

This study included data from a sample of caregivers across four European countries. The results provide a greater understanding of who is providing care to patients with MPM, the specific tasks undertaken daily and which tasks caregivers found most troublesome. It also explores caregiver burden and impact on physical and emotional health and impairment of caregiver work and activity.

An MPM diagnosis may require changes in daily activities and work and may result in changed roles within the family unit [40]. Most caregivers in this study lived with and were a family member of the patient (9 in 10) and 7 in 10 were their spouse/partner. This study also found caregivers of patients with MPM engaged in a wide range of daily activities including, supporting patients travelling out of the home, driving to work/hospital/appointments and helping with meals and medication management. Other studies have also shown that caregivers who are family members may be expected to spend a lot of time providing practical support involving such tasks [41].

In addition to various practical tasks, most caregivers in this study reported that they were providing daily emotional support and encouragement to the patient, and this activity was cited as being one of the top three most troublesome caregiving activities. Our findings were similar to a study of caregiving in lung cancer patients where a third of caregivers reported managing patients’ emotions as being one of the most challenging tasks they perform [42], and similar findings have been observed among caregivers of patients with other cancers [43]. The results also indicated potential cultural differences may impact the perception of burden, for example, we found one in three caregivers in France and Italy reported providing emotional support was one of the top three most troublesome tasks compared with two in three in Spain and the UK. This suggests cultural differences may impact perceptions of the burden of specific caregiving tasks. Variations in compensation available to MPM patients across countries may also play a role. For example, comprehensive compensation is available in France and the UK at 4.60 and 1.03 times the median income per year, respectively, [44] but in Spain, many cases may be under-recognised under existing compensation systems [45].

A cancer diagnosis, as well as the subsequent phases of the disease and its treatment, can be a source of intense stress both for the patient and the family as they face the challenge of uncertainty, treatment routines, and the threat of treatment failure [46]. Poor prognosis for patients with MPM and lack of treatment options may cause ever-increasing emotional challenges for the patient; many MPM patients and caregivers indicate their psychosocial care needs are not being met [47]. Harrison et al. showed caregivers receiving a referral to a specialist palliative care team were significantly more satisfied than those that did not, particularly because of the emotional support provided by these services [48]. Further, many patients may experience resentment and blame if their cancer is attributable to their work environment [30]. These factors are likely to cause disappointment and stress for the caregiver [20] as well as requiring them to support the patient through these challenges, likely resulting in stress, negative emotions, and role strain, which contributes to physical and psychological health impairment [46]. Warby et al. reported even in cases where caregivers were satisfied with treatment, they reported needing more communication about available treatments, end-of-life assistance and support after the patient’s death [49].

The level of perceived burden experienced by caregivers of patients with MPM observed in this study was higher than the burden reported for caregivers of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients [50] and advanced cancer patients in a palliative day care setting [51], but similar to the levels of burden observed for caregivers of cancer patients within six months of diagnosis [52]. Our finding that poor ECOG performance score was a key driver of caregiver burden in MPM is consistent with findings in other cancers [50, 53]. Of note, our study found that caregivers of patients receiving BSC had lower burden than caregivers of patients receiving 1L maintenance and 2L + SACT. These patients may be receiving more external support in a palliative setting which could lead to lower burden on the informal caregiver. Further research should seek to identify optimal times when additional support may be introduced to support both the patient and caregiver to alleviate burden.

An earlier study reported patients with MPM receiving maintenance therapy had better health states and quality of life (QoL) than patients receiving 1L SACT or 2L + SACT [31]. However, we found that the caregivers of patients receiving 1L maintenance were experiencing similar burden to caregivers of patients that had progressed to 2L SACT. This result may reflect patients experiencing ongoing treatment cycles and visits for treatment/ management. This will not only have a psychological effect on the patient and caregiver but also involve more time spent travelling out of the home and driving patients to hospital, both tasks caregivers reported as being among the most troublesome.

Across all subgroups, the levels of burden observed for caregivers of patients with MPM in this study exceeded the threshold for risk of depression identified by Schreiner et al. [36]. Caregivers are at risk for several mental health problems including depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and social isolation [54, 55]. Evidence regarding the potential psychological costs of caregiving and its relationship to caregiver burden has been growing [56]. A recent study found that subjective caregiver burden, as measured by the ZBI, was associated with poorer physical and mental health for caregivers [57]. Studies using other measures of caregiver burden have found a similar positive relationship between increased burden and increased risk of developing anxiety and depression [58]. Emotional concerns were also one of the most identified problems for caregivers in a literature review on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer [59] and declines in psychological wellbeing have been reported for caregivers of lung cancer patients [60, 61]. Caregiver burden is frequently overlooked by physicians and the findings of this study further demonstrate the need for caregiver assessment and intervention [54].

Despite caregivers being essential to the healthcare system, the health of caregivers is not being prioritized. Many caregivers have been described as “hidden patients” [62], susceptible to a variety of stress-related illnesses (including depression) that often go untreated because there is no one to attend to the caregivers’ responsibilities while they recover [63]. Without providing adequate resources in long-term care services, demands on caregivers’ attention and time are likely increased, putting them at risk of developing serious mental and physical health problems. Only a quarter of the caregivers in this study reported that caregiving had not impacted their health. It is important that caregivers are supported in taking care of their own health needs as well as those of the patient they care for. However, for some, this will require them to overcome a culture that encourages caregivers to meet the needs of the patient at the expense of their own [64]. Where systems have been found to be inadequate or not supportive enough of caregivers, levels of anxiety and depression have remained high [65]. Caregivers that have received psychological and social resources reported lower levels of depression than those that have not [66]. In particular, support targeted at specific caregivers’ needs is often the most helpful [67].

In addition to our study providing insights into the burden of caregiving in MPM and the potential impacts to emotional and physical health, we also found that caregivers spent 40% of their daily activities impaired and those that were still working had 12% absenteeism and 25% presenteeism during the past seven days. Family and medical leave policy reform is needed to support caregivers. For example, in the UK, an employer is not legally obligated to pay a caregiver that takes time off to provide care, likely leading to caregivers returning to work before they are ready. There is growing interest from insurers and healthcare systems to understand caregiver burden both for caregivers themselves, the patients and the impact of caregiving on society. Studies such as this are vital across diseases if the required support is to be identified and provided to caregivers and further incorporated into insurer and healthcare system decision making. Importantly, caregiver burden has been found to be associated with factors linked to disease progression such as the ECOG performance score of patients [50] and patient QoL [64], with burden for caregivers increasing as ECOG performance score declines or QoL deteriorates. Recently, the European Medicines Agency and US Food and Drug Administration have approved nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy in the 1L setting [68, 69] based on the results of a clinical trial which demonstrated an increased time to QoL deterioration and prolonged survival [70,71,72,73]. Given the relationship between clinical outcomes and caregiver burden, improvements in treatment options for patients with MPM may be expected to lead to improved outcomes for caregivers also. Payers should consider caregiver burden when economically evaluating potential new treatments.

Study strengths/limitations

A key strength of this study was the geographical spread of the primary caregivers, which provided a diverse and sizable caregiver population for evaluating the impact of this rare cancer on caregivers of patients in routine clinical care in Europe. As with all point-in-time study designs, the current study provides a snapshot of caregiver status only; therefore, the status of caregivers prior to taking on their caregiving role is unknown.

A limitation of this study was that it relied on the accuracy of recall by caregivers, although the selection of validated instruments that require short recall time was expected to minimise these effects. Caregiver inclusion was based on their willingness to participate, which has an inherent risk of selection bias. However, the demography of the patients with caregivers that did not provide a CSC was similar to that of those who did provide a CSC. Finally, as this study was purely descriptive, differences observed may not be statistically meaningful.

Conclusion

The results of this multi-country, real-world study provide evidence that caring for patients with MPM involves a range of burdensome activities impacting caregivers’ emotional and physical health and their ability to undertake daily activities. Future innovation in the management of MPM will need to ensure improved outcomes for patients are not at the detriment of caregivers, and it is crucial caregivers receive the necessary support to carry out this important role. Interventions that maintain patient ECOG performance score and QoL by delaying disease progression are expected to improve caregiver outcomes. Focussing on maintaining caregiver health alongside the health of patients with MPM will also improve outcomes for caregivers and thus their ability to provide essential care for those with MPM.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. BMS policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/independent-research/data-sharingrequest-process.html.

References

Corfiati, M., Scarselli, A., Binazzi, A., Di Marzio, D., Verardo, M., Mirabelli, D., Gennaro, V., Mensi, C., Schallemberg, G., Merler, E., Negro, C., Romanelli, A., Chellini, E., Silvestri, S., Cocchioni, M., Pascucci, C., Stracci, F., Romeo, E., Trafficante, L., … ReNa, M. W. G. (2015). Epidemiological patterns of asbestos exposure and spatial clusters of incident cases of malignant mesothelioma from the Italian national registry. BMC Cancer, 15, 286.

Noonan, C. W. (2017). Environmental asbestos exposure and risk of mesothelioma. Ann Transl Med, 5(11), 234.

Reid, A., de Klerk, N. H., Magnani, C., Ferrante, D., Berry, G., Musk, A. W., & Merler, E. (2014). Mesothelioma risk after 40 years since first exposure to asbestos: A pooled analysis. Thorax, 69(9), 843–850.

Wilk, E., & Krowczynska, M. (2021). Malignant mesothelioma and asbestos exposure in Europe: Evidence of spatial clustering. Geospat Health, 16(1), 91–102.

Beckett, P., Edwards, J., Fennell, D., Hubbard, R., Woolhouse, I., & Peake, M. D. (2015). Demographics, management and survival of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma in the national lung cancer audit in England and Wales. Lung Cancer, 88(3), 344–348.

Marinaccio, A., Binazzi, A., Bonafede, M., Di Marzio, D., Scarselli, A., & Regional Operating, C. (2018). Epidemiology of malignant mesothelioma in Italy: Surveillance systems, territorial clusters and occupations involved. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 10(Suppl 2), S221–S227.

Bibby, A. C., Tsim, S., Kanellakis, N., Ball, H., Talbot, D. C., Blyth, K. G., Maskell, N. A., & Psallidas, I. (2016). Malignant pleural mesothelioma: An update on investigation, diagnosis and treatment. European Respiratory Reviews, 25(142), 472–486.

Chouaid, C., Assie, J. B., Andujar, P., Blein, C., Tournier, C., Vainchtock, A., Scherpereel, A., Monnet, I., & Pairon, J. C. (2018). Determinants of malignant pleural mesothelioma survival and burden of disease in France: A national cohort analysis. Cancer Medicine, 7(4), 1102–1109.

Society AC. (2020). Survival rates for mesothelioma. Retrieved January 2022, from Survival Rates for Mesothelioma

Zhai, Z., Ruan, J., Zheng, Y., Xiang, D., Li, N., Hu, J., Shen, J., Deng, Y., Yao, J., Zhao, P., Wang, S., Yang, S., Zhou, L., Wu, Y., Xu, P., Lyu, L., Lyu, J., Bergan, R., Chen, T., & Dai, Z. (2021). Assessment of global trends in the diagnosis of mesothelioma From 1990 to 2017. JAMA Network Open, 4(8), e2120360.

Bianchi, C., & Bianchi, T. (2007). Malignant mesothelioma: Global incidence and relationship with asbestos. Industrial Health, 45(3), 379–387.

Burdorf, A., Dahhan, M., & Swuste, P. (2003). Occupational characteristics of cases with asbestos-related diseases in The Netherlands. Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 47(6), 485–492.

Frost, G. (2013). The latency period of mesothelioma among a cohort of British asbestos workers (1978–2005). British Journal of Cancer, 109(7), 1965–1973.

Novello, S., Pinto, C., Torri, V., Porcu, L., Di Maio, M., Tiseo, M., Ceresoli, G., Magnani, C., Silvestri, S., Veltri, A., Papotti, M., Rossi, G., Ricardi, U., Trodella, L., Rea, F., Facciolo, F., Granieri, A., Zagonel, V., & Scagliotti, G. (2016). The third Italian consensus conference for malignant pleural mesothelioma: State of the art and recommendations. Critical Reviews in Oncology Hematology, 104, 9–20.

Montanaro, F., Rosato, R., Gangemi, M., Roberti, S., Ricceri, F., Merler, E., Gennaro, V., Romanelli, A., Chellini, E., Pascucci, C., Musti, M., Nicita, C., Barbieri, P. G., Marinaccio, A., Magnani, C., & Mirabelli, D. (2009). Survival of pleural malignant mesothelioma in Italy: A population-based study. International Journal of Cancer, 124(1), 201–207.

Magge, D., Zenati, M. S., Austin, F., Mavanur, A., Sathaiah, M., Ramalingam, L., Jones, H., Zureikat, A. H., Holtzman, M., Ahrendt, S., Pingpank, J., Zeh, H. J., Bartlett, D. L., & Choudry, H. A. (2014). Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: Prognostic factors and oncologic outcome analysis. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 21(4), 1159–1165.

Stewart, D. J., Martin-Ucar, A. E., Edwards, J. G., West, K., & Waller, D. A. (2005). Extra-pleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma: The risks of induction chemotherapy, right-sided procedures and prolonged operations. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, 27(3), 373–378.

Baas, P., Fennell, D., Kerr, K. M., Van Schil, P. E., Haas, R. L., Peters, S., & Committee, E. G. (2015). Malignant pleural mesothelioma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology, 26(Suppl 5), v31-39.

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). (2022). ESMO standard operating procedures (SOPs) for clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) and ESMO magnitude of clinical benefit (ESMO-MCBS) and ESMO scale for clinical actionability of molecular targets (ESCAT) scores. Retrieved 18 May 2022, from https://www.esmo.org/content/download/77789/1426712/file/ESMO-Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-Standard-Operating-Procedures.pdf. Accessed 18 May 2022.

Granieri, A., Tamburello, S., Tamburello, A., Casale, S., Cont, C., Guglielmucci, F., & Innamorati, M. (2013). Quality of life and personality traits in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma and their first-degree caregivers. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 1193–1202.

Tinkler, M., Royston, R., & Kendall, C. (2017). Palliative care for patients with mesothelioma. British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London, England), 78(4), 219–225.

Moore, S., Darlison, L., & Tod, A. M. (2010). Living with mesothelioma. A literature review. European Journal of Cancer Care (England), 19(4), 458–468.

Li, Y. Q., Zhang, M. H., Wang, Q. Q., Liu, J. J., & Yao, H. Y. (2018). The caregiver burden and related factors on quality of life among caregivers for patients with lung cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, 40(6), 467–473.

Liu, Z., Heffernan, C., & Tan, J. (2020). Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. International Jorunal of Nursing Sciences, 7(4), 438–445.

Bonafede, M., Granieri, A., Binazzi, A., Mensi, C., Grosso, F., Santoro, G., Franzoi, I. G., Marinaccio, A., & Guglielmucci, F. (2020). Psychological distress after a diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma in a group of patients and caregivers at the national priority contaminated site of Casale Monferrato. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4353.

Angelo, J. K., Egan, R., & Reid, K. (2013). Essential knowledge for family caregivers: A qualitative study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 19(8), 383–388.

Peña-Longobardo, L. M., & Oliva-Moreno, J. (2021). The economic value of non-professional care: A Europe-wide analysis. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2021.149

Commission, E., Directorate-General for Employment, S. A., Inclusion, & Zigante, V. (2018). Informal care in Europe : exploring formalisation, availability and quality: Publications Office.

Roche, V. (2009). The hidden patient: Addressing the caregiver. American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 337(3), 199–204.

Ball, H., Moore, S., & Leary, A. (2016). A systematic literature review comparing the psychological care needs of patients with mesothelioma and advanced lung cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25, 62–67.

Moore, A., Bennett, B., Taylor-Stokes, G., McDonald, L., & Daumont, M. J. (2022). Malignant pleural mesothelioma: Treatment patterns and humanistic burden of disease in Europe. BMC Cancer, 22(1), 693.

Bedard, M., Molloy, D. W., Squire, L., Dubois, S., Lever, J. A., & O’Donnell, M. (2001). The zarit burden interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist, 41(5), 652–657.

Seng, B. K., Luo, N., Ng, W. Y., Lim, J., Chionh, H. L., Goh, J., & Yap, P. (2010). Validity and reliability of the Zarit Burden Interview in assessing caregiving burden. Ann Acad Med Singap, 39(10), 758–763.

Hébert, R., Bravo, G., & Préville, M. (2000). Reliability, validity and reference values of the zarit burden interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Canadian Journal on Aging, 19(4), 494–507.

Zarit, S. H., & Zarit, J. M. (1987). Instructions for the burden interview. Unpublished manuscript, Technical document, University park, PA: Penylvania state University.

Schreiner, A. S., Morimoto, T., Arai, Y., & Zarit, S. (2006). Assessing family caregiver’s mental health using a statistically derived cut-off score for the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging & Mental Health, 10(2), 107–111.

Reilly, M. C., Zbrozek, A. S., & Dukes, E. M. (1993). The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics, 4(5), 353–365.

Reilly Associates. (2021). WPAI translations. from http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_Translations.html. Accessed 18 May 2022.

StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

Granieri, A., Bonafede, M., Marinaccio, A., Iavarone, I., Marsili, D., & Franzoi, I. G. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 and asbestos exposure: Can our experience with mesothelioma patients help us understand the psychological consequences of COVID-19 and develop interventions? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 584320.

Nausheen, B., Gidron, Y., Peveler, R., & Moss-Morris, R. (2009). Social support and cancer progression: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 67(5), 403–415.

Mosher, C. E., Jaynes, H. A., Hanna, N., & Ostroff, J. S. (2013). Distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients: An examination of psychosocial and practical challenges. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(2), 431–437.

Carey, P. J., Oberst, M. T., McCubbin, M. A., & Hughes, S. H. (1991). Appraisal and caregiving burden in family members caring for patients receiving chemotherapy. Oncology Nursing Forum, 18(8), 1341–1348.

Lee, K. M., Godderis, L., Furuya, S., Kim, Y. J., & Kang, D. (2021). Comparison of asbestos victim relief available outside of conventional occupational compensation schemes. International Journal Environmental Research Public Health, 18(10), 5236.

Garcia-Gomez, M., Menendez-Navarro, A., & Lopez, R. C. (2015). Asbestos-related occupational cancers compensated under the Spanish national insurance system, 1978–2011. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 21(1), 31–39.

Wozniak, K., & Izycki, D. (2014). Cancer: A family at risk. Prz Menopauzalny, 13(4), 253–261.

Breen, L. J., Huseini, T., Same, A., Peddle-McIntyre, C. J., & Lee, Y. C. G. (2022). Living with mesothelioma: A systematic review of patient and caregiver psychosocial support needs. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(7), 1904–1916.

Harrison, M., Gardiner, C., Taylor, B., Ejegi-Memeh, S., & Darlison, L. (2021). Understanding the palliative care needs and experiences of people with mesothelioma and their family carers: An integrative systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 35(6), 1039–1051.

Warby, A., Dhillon, H. M., Kao, S., & Vardy, J. L. (2019). A survey of patient and caregiver experience with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(12), 4675–4686.

Wood, R., Taylor-Stokes, G., Smith, F., Chirita, O. C., & Torralba, C. C. (2018). The humanistic burden of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: What are the key drivers of caregiver burden? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36(7_suppl), 149–149.

Harding, R., Gao, W., Jackson, D., Pearson, C., Murray, J., & Higginson, I. J. (2015). Comparative analysis of informal caregiver burden in advanced cancer, dementia, and acquired brain injury. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 50(4), 445–452.

Garcia-Torres, F., Jablonski, M. J., Gomez Solis, A., Jaen-Moreno, M. J., Galvez-Lara, M., Moriana, J. A., Moreno-Diaz, M. J., & Aranda, E. (2020). Caregiver burden domains and their relationship with anxiety and depression in the first six months of cancer diagnosis. International Journal Environmental Research Public Health, 17(11), 4101.

Kahriman, F., & Zaybak, A. (2015). Caregiver burden and perceived social support among caregivers of patients with cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 16(8), 3313–3317.

Adelman, R. D., Tmanova, L. L., Delgado, D., Dion, S., & Lachs, M. S. (2014). Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA, 311(10), 1052–1060.

Kleine, A. K., Hallensleben, N., Mehnert, A., Honig, K., & Ernst, J. (2019). Psychological interventions targeting partners of cancer patients: A systematic review. Critical Reviews in Oncology Hematology, 140, 52–66.

Sherwood, P. R., Given, C. W., Given, B. A., & von Eye, A. (2005). Caregiver burden and depressive symptoms: Analysis of common outcomes in caregivers of elderly patients. Journal of Aging and Health, 17(2), 125–147.

Fekete, C., Tough, H., Siegrist, J., & Brinkhof, M. W. (2017). Health impact of objective burden, subjective burden and positive aspects of caregiving: An observational study among caregivers in Switzerland. British Medical Journal Open, 7(12), e017369.

Denno, M. S., Gillard, P. J., Graham, G. D., DiBonaventura, M. D., Goren, A., Varon, S. F., & Zorowitz, R. (2013). Anxiety and depression associated with caregiver burden in caregivers of stroke survivors with spasticity. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94(9), 1731–1736.

Stenberg, U., Ruland, C. M., & Miaskowski, C. (2010). Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19(10), 1013–1025.

Grant, M., Sun, V., Fujinami, R., Sidhu, R., Otis-Green, S., Juarez, G., Klein, L., & Ferrell, B. (2013). Family caregiver burden, skills preparedness, and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40(4), 337–346.

Kim, Y., Duberstein, P. R., Sorensen, S., & Larson, M. R. (2005). Levels of depressive symptoms in spouses of people with lung cancer: Effects of personality, social support, and caregiving burden. Psychosomatics, 46(2), 123–130.

Borkan, J., Reis, S., & Steinmetz, D. (1999). The hidden patient: an incident that changed my professional life. Patients and doctors: life-changing stories from primary care. (Vol. 173). Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Hill, J. (2003). The hidden patient. Lancet, 362, 1682.

Borges, E. L., Franceschini, J., Costa, L. H., Fernandes, A. L., Jamnik, S., & Santoro, I. L. (2017). Family caregiver burden: The burden of caring for lung cancer patients according to the cancer stage and patient quality of life. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia, 43(1), 18–23.

Hudson, P. L., Thomas, K., Trauer, T., Remedios, C., & Clarke, D. (2011). Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(3), 522–534.

Nijboer, C., Tempelaar, R., Triemstra, M., van den Bos, G. A., & Sanderman, R. (2001). The role of social and psychologic resources in caregiving of cancer patients. Cancer, 91(5), 1029–1039.

Ryan, P. J., Howell, V., Jones, J., & Hardy, E. J. (2008). Lung cancer, caring for the caregivers. A qualitative study of providing pro-active social support targeted to the carers of patients with lung cancer. Palliative Medicine, 22(3), 233–238.

Opdivo™ (nivolumab) summary of product characteristics. (Available at) https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/opdivo-epar-product-information_en.pdf Date: 2021 Date accessed: 18 May 2022.

Opdivo® (nivolumab) prescribing information. (Available at) https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_opdivo.pdf Date: 2021 Date accessed: 18 May 2022.

Nakajima, E. C., Vellanki, P. J., Larkins, E., Chatterjee, S., Mishra-Kalyani, P. S., Bi, Y., Qosa, H., Liu, J., Zhao, H., Biable, M., Hotaki, L. T., Shen, Y. L., Pazdur, R., Beaver, J. A., Singh, H., & Donoghue, M. (2022). FDA approval summary: Nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for the treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma. Clinical Cancer Research, 28(3), 446–451.

Scherpereel, A., Antonia, S., Grossi, F., Kowalski, D., Zalcman, G., Nowak, A., Fujimoto, N., Peters, S., Tsao, A., Mansfield, A., Popat, S., Sun, X., Padilla, B., Aanur, P., Daumont, M., Bennett, B., McKenna, M., & Baas, P. (2020). LBA1 first-line nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) versus chemotherapy (chemo) for the treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from CheckMate 743. Annals of Oncology, 31(S7), S1441.

Peters, S., Scherpereel, A., Cornelissen, R., Oulkhouir, Y., Greillier, L., Kaplan, M. A., Talbot, T., Monnet, I., Hiret, S., Baas, P., Nowak, A. K., Fujimoto, N., Tsao, A. S., Mansfield, A. S., Popat, S., Zhang, X., Hu, N., Balli, D., Spires, T., & Zalcman, G. (2022). First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy in patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma: 3-year outcomes from CheckMate 743. Annals of Oncology, 33(5), 488–499.

Scherpereel, A., Antonia, S., Bautista, Y., Grossi, F., Kowalski, D., Zalcman, G., Nowak, A. K., Fujimoto, N., Peters, S., Tsao, A. S., Mansfield, A. S., Popat, S., Sun, X., Lawrance, R., Zhang, X., Daumont, M. J., Bennett, B., McKenna, M., & Baas, P. (2022). First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy for the treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma: Patient-reported outcomes in CheckMate 743. Lung Cancer, 167, 8–16.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Victoria A. Davis PhD and Daniel Green BSc of Adelphi Real World and was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. They have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from Bristol Myers Squibb.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM, BB, and MD contributed to the design of the study and data interpretation. GT contributed to the design of the study and data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MD and BB are employees of Bristol Myers Squibb. GT and AM are employees of Adelphi Real World and were paid consultants to Bristol Myers Squibb in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Western International Review Board (protocol: CA209-8LD).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, A., Bennett, B., Taylor-Stokes, G. et al. Caregivers of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: who provides care, what care do they provide and what burden do they experience?. Qual Life Res 32, 2587–2599 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03410-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03410-4