Abstract

Purpose

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), including global health and construct-specific measures, are collected across healthcare systems. Efforts should be made to reduce data collection burden and individualize survey administration to patient needs. Our study evaluated the ability of utilizing items on a global health measure to identify patients who may require additional screening.

Methods

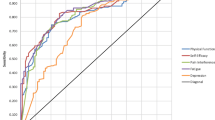

A cross-sectional study was conducted of patients who completed PROMIS Global Health (GH) as part of routine care, as well as additional construct-specific surveys, in a large healthcare system from 1/1/2016 to 12/31/2018. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis identified optimal thresholds for PROMIS GH items identifying clinically meaningful thresholds on construct-specific PROMs: PHQ-9 score ≥10, Neuro-QoL Cognitive Function, PROMIS Physical Function, and Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities T-score ≤40, PROMIS Anxiety, Fatigue, Sleep Disturbance, and Pain Interference T-score ≥60.

Results

There were 206,685 patients who completed PROMIS GH and additional construct-specific surveys. Scores ≤3 on PROMIS GH item 10 (emotional problems) had 90.0% sensitivity (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.821) for identifying patients with moderate-severe depressive symptoms on PHQ-9. Similarly high sensitivities and AUCs were demonstrated for PROMIS GH items assessing mental and physical health, fatigue, and pain to identify poor scores on their corresponding construct-specific PROMs.

Conclusions

Our study provides preliminary support for the ability of utilizing PROMIS GH items as screening tools to identify patients with poor scores on additional construct-specific PROMs. Through directing construct-specific PROMs to patients for whom they are most applicable, survey burden could be reduced for many patients, allowing a more efficient and targeted use of PROMs in healthcare decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material

Data not published within the article are available and will be shared by reasonable request.

Code availability

SAS code will be shared by reasonable request.

References

Rumsfeld, J. S., Alexander, K. P., Goff, D. C., Jr., Graham, M. M., Ho, P. M., Masoudi, F. A., et al. (2013). Cardiovascular health: The importance of measuring patient-reported health status: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 127(22), 2233–2249. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182949a2e

Katzan, I. L., Thompson, N. R., Lapin, B., & Uchino, K. (2017). Added Value of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Stroke Clinical Practice. Journal of American Heart Association, 6(7), e005356. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.005356

Basch, E., Deal, A. M., Dueck, A. C., Scher, H. I., Kris, M. G., Hudis, C., et al. (2017). Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA, 318(2), 197–198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7156

Calvert, M., Blazeby, J., Altman, D. G., Revicki, D. A., Moher, D., Brundage, M. D., et al. (2013). Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: The CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA, 309(8), 814–822. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.879

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration (2009). Guidance for industry. Patient-Reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download. Accessed May 25, 2022.

Wasson, J., Keller, A., Rubenstein, L., Hays, R., Nelson, E., & Johnson, D. (1992). Benefits and obstacles of health status assessment in ambulatory settings. The clinician’s point of view. The Dartmouth Primary Care COOP Project. Medical Care, 30(5), MS42–49 https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199205001-00004.

Philpot, L. M., Barnes, S. A., Brown, R. M., Austin, J. A., James, C. S., Stanford, R. H., et al. (2018). Barriers and benefits to the use of patient-reported outcome measures in routine clinical care: A qualitative study. American Journal of Medical Quality, 33(4), 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860617745986

National Quality Forum. Patient-Reported Outcomes: Best Practices on Selection and Data Collection—Final Technical Report (September 2, 2020). https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2020/09/Patient-Reported_Outcomes__Best_Practices_on_Selection_and_Data_Collection_-_Final_Technical_Report.aspx.

Morgan, M. (May 28, 2021). The virtual care strategy checklist: Implementing a contactless check-in. https://medcitynews.com/2021/03/THE-VIRTUAL-CARE-STRATEGY-CHECKLIST-IMPLEMENTING-A-CONTACTLESS-CHECK-IN/. Accessed January 31, 2022.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

Maurer, D. M., Raymond, T. J., & Davis, B. N. (2018). Depression: Screening and diagnosis. American Family Physician, 98(8), 508–515.

Levis, B., Sun, Y., He, C., Wu, Y., Krishnan, A., Bhandari, P. M., et al. (2020). Accuracy of the PHQ-2 alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 for screening to detect major depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 323(22), 2290–2300. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6504

Mayo, N. E. (2015). Dictionary of quality of life and health outcomes measurement (1st ed.). International Society for Quality of Life Research.

Evans, J. P., Smith, A., Gibbons, C., Alonso, J., & Valderas, J. M. (2018). The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): A view from the UK. Patient Related Outcome Measures, 9, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S141378

Blumenthal, K. J., Chang, Y., Ferris, T. G., Spirt, J. C., Vogeli, C., Wagle, N., et al. (2017). Using a self-reported global health measure to identify patients at high risk for future healthcare utilization. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(8), 877–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4041-y

Seneviratne, M. G., Bozkurt, S., Patel, M. I., Seto, T., Brooks, J. D., Blayney, D. W., et al. (2019). Distribution of global health measures from routinely collected PROMIS surveys in patients with breast cancer or prostate cancer. Cancer, 125(6), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31895

Kobau, R., Cui, W., & Zack, M. M. (2017). Adults with an epilepsy history fare significantly worse on positive mental and physical health than adults with other common chronic conditions-Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey and Patient Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS) Global Health Scale. Epilepsy & Behavior, 72, 182–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.04.047

Barile, J. P., Reeve, B. B., Smith, A. W., Zack, M. M., Mitchell, S. A., Kobau, R., et al. (2013). Monitoring population health for Healthy People 2020: Evaluation of the NIH PROMIS(R) Global Health, CDC Healthy Days, and satisfaction with life instruments. Quality of Life Research, 22(6), 1201–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0246-z

Katzan, I., Speck, M., Dopler, C., Urchek, J., Bielawski, K., Dunphy, C., et al. (2011). The knowledge program: An innovative, comprehensive electronic data capture system and warehouse. American Medical Informatics Association Annual Symposium Proceedings, 2011, 683–692.

Hays, R. D., Bjorner, J. B., Revicki, D. A., Spritzer, K. L., & Cella, D. (2009). Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of Life Research, 18(7), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Global Health. A brief guide to the PROMIS Global Health Instruments. 3/6/2017. https://staging.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Global_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Last accessed August 8, 2022

Gershon, R. C., Lai, J. S., Bode, R., Choi, S., Moy, C., Bleck, T., et al. (2012). Neuro-QOL: Quality of life item banks for adults with neurological disorders: Item development and calibrations based upon clinical and general population testing. Quality of Life Research, 21(3), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9958-8

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011

HealthMeasures. PROMIS® Reference Populations. https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis/reference-populations. Accessed July 15, 2022.

HealthMeasures. PROMIS® Score Cut Points. https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis/promis-score-cut-points. Accessed July 15, 2022.

HealthMeasures. Neuro-QoLTM. https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/neuro-qol. Accessed July 15, 2022.

Dejesus, R. S., Vickers, K. S., Melin, G. J., & Williams, M. D. (2007). A system-based approach to depression management in primary care using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 82(11), 1395–1402. https://doi.org/10.4065/82.11.1395

Recinos, P. F., Dunphy, C. J., Thompson, N., Schuschu, J., Urchek, J. L., 3rd., & Katzan, I. L. (2016). Patient satisfaction with collection of patient-reported outcome measures in routine care. Advances in Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0463-x

Lapin, B., Udeh, B., Bautista, J. F., & Katzan, I. L. (2018). Patient experience with patient-reported outcome measures in neurologic practice. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000006198

Lavidor, M., Weller, A., & Babkoff, H. (2003). How sleep is related to fatigue. The British Journal of Health Psychology, 8(Pt 1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910703762879237

Sapra, A., Bhandari, P., Sharma, S., Chanpura, T., & Lopp, L. (2020). Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus, 12(5), e8224. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8224

Kattan, M. W., & Vickers, A. J. (2020). Statistical Analysis and Reporting Guidelines for CHEST. Chest, 158(1S), S3–S11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.10.064

Vickers, A. J., & Elkin, E. B. (2006). Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Medical Decision Making, 26(6), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X06295361

Streiner, D. L. (2002). Breaking up is hard to do: The heartbreak of dichotomizing continuous data. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47(3), 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370204700307

Jones, P. W. (2002). Interpreting thresholds for a clinically significant change in health status in asthma and COPD. European Respiratory Journal, 19(3), 398–404. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00063702

Pilz, M. J., Aaronson, N. K., Arraras, J. I., Caocci, G., Efficace, F., Groenvold, M., et al. (2021). Evaluating the Thresholds for Clinical Importance of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL in patients receiving palliative treatment. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 24(3), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0159

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Review Board (#07–591). Because the study consisted of analyses of pre-existing data, the requirement for patient informed consent was waived.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lapin, B., Katzan, I.L. PROMIS global health: potential utility as a screener to trigger construct-specific patient-reported outcome measures in clinical care. Qual Life Res 32, 105–113 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03206-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03206-y