Abstract

Purpose

Healthy People 2020 identified health-related quality of life and well-being (WB) as indicators of population health for the next decade. This study examined the measurement properties of the NIH PROMIS® Global Health Scale, the CDC Healthy Days items, and associations with the Satisfaction with Life Scale.

Methods

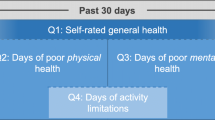

A total of 4,184 adults completed the Porter Novelli’s HealthStyles mailed survey. Physical and mental health (9 items from PROMIS Global Scale and 3 items from CDC Healthy days measure), and 4 WB factor items were tested for measurement equivalence using multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis.

Results

The CDC items accounted for similar variance as the PROMIS items on physical and mental health factors; both factors were moderately correlated with WB. Measurement invariance was supported across gender and age; the magnitude of some factor loadings differed between those with and without a chronic medical condition.

Conclusions

The PROMIS, CDC, and WB items all performed well. The PROMIS items captured a broad range of functioning across the entire continuum of physical and mental health, while the CDC items appear appropriate for assessing burden of disease for chronic conditions and are brief and easily interpretable. All three measures under study appear to be appropriate measures for monitoring several aspects of the Healthy People 2020 goals and objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2011). Foundation health measures. Healthy People 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2000). Measuring Healthy Days. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hays, R. D., Bjorner, J. B., Revicki, D. A., Spritzer, K. L., & Cella, D. (2009). Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of Life Research, 18(7), 873–880.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Moriarty, D. G., Kobau, R., Zack, M. M., & Zahran, H. S. (2005). Tracking Healthy Days—A window on the health of older adults. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2(3), A16.

Fayers, P. M., & Machin, D. (2007). Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. Chichester: Wiley.

National Center for Health Statistics. (1994). In Proceedings of the 1993 NCHS conference on the cognitive aspects of self-reported health status. Unpublished manuscript.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (1993). Consultation on functional status surveillance for states and communities: Decatur, Georgia, June 4–5, 1992: Meeting report. US Dept. of Health & Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Booske, B. C., Kindig, D. A., Remington, P. L., Kempf, A. M., & Peppard, P. E. (2006). How should we measure health-related quality of life in Wisconsin? University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute Brief Report (Vol. 1). University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

Moriarty, D. G., Zack, M. M., & Kobau, R. (2003). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Healthy Days measures—Population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 1, 37.

Jiang, Y., & Hesser, J. E. (2009). Using item response theory to analyze the relationship between health-related quality of life and health risk factors. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6(1), 1–10.

Mielenz, T., Jackson, E., Currey, S., DeVellis, R., & Callahan, L. F. (2006). Psychometric properties of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health-related quality of life (CDC HRQOL) items in adults with arthritis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 66–84.

Horner-Johnson, W., Suzuki, R., Krahn, G., Andresen, E., Drum, C., & The RRTC Expert Panel on Health. (2010). Structure of health-related quality of life among people with and without functional limitations. Quality of Life Research, 19(7), 977–984.

Parrish, R. G. (2010). Measuring population health outcomes. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(4), 1–11.

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194.

Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index. (2008). www.well-beingindex.com.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 402–435.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: Americans’ perceptions of life quality. New York: Plenum Press.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727.

Bann, C. M., Kobau, R., Lewis, M. A., Zack, M. M., Luncheon, C., & Thompson, W. W. (2011). Development and psychometric evaluation of the public health surveillance well-being scale. Quality of Life Research, 21(6), 1031–1043.

Porter Novelli International. (2010). HealthStyles survey. Washington, DC: Porter Novelli.

Pavot, W., Diener, E., Colvin, C. R., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Further validation of the satisfaction with life scale: Evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57, 149–161.

Blais, M. R., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Brière, N. M. (1989). L’échelle de satisfaction de vie: Validation canadienne-française du” Satisfaction with Life Scale”. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 21(2), 210–223.

Magnus, K., Diener, E., Fujita, F., & Pavot, W. (1993). Extraversion and neuroticism as predictors of objective life events: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 1046–1053.

Pavot, W. (2008). The assessment of subjective well-being. New York: The Guilford Press.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152.

Larsen, R. J., & Eid, M. (2008). Ed Diener and the science of subjective well-being. New York: The Guilford Press.

Kobau, R., Sniezek, J., Zack, M. M., Lucas, R. E., & Burns, A. (2010). Well-being assessment: An evaluation of well-being scales for public health and population estimates of well-being among US adults. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2, 272–297.

Diener, E. (2009). The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. New York: Springer.

Muthen, B. O., & Muthen, L. K. (2010). Mplus statistical analysis with latent variables (Version 6.0). Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen.

Flora, D., & Curran, P. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods, 9(4), 466–491.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods Research, 21, 230–258.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Gregorich, S. E. (2006). Do self-report instruments allow meaningful comparisons across diverse population groups? Testing measurement invariance using the confirmatory factor analysis framework. Medical Care, 44(11 Suppl 3), S78–S94.

Vandenberg, R. J. (2002). Toward a further understanding of and improvement in measurement invariance methods and procedures. Organizational Research Methods, 5(2), 139–158.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255.

Little, T. D. (1997). Mean and covariance structures (MACS) Analyses of cross-cultural data: Practical and theoretical issues. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32, 53–76.

Gandek, B., Ware, J. E., Jr, Aaronson, N. K., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Bjorner, J., et al. (1998). Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the SF-36 in eleven countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International quality of life assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1149–1158.

Albrecht, G. L., & Devlieger, P. J. (1999). The disability paradox: High quality of life against all odds. Social Science and Medicine, 48(8), 977–988.

Krahn, G., Fujiura, G., Drum, C., Cardinal, B., Nosek, M., & RRTC Expert Panel on Health Measurement. (2009). The dilemma of measuring perceived health status in the context of disability. Disability and Health Journal, 2(2), 49–56.

Schwartz, C. E., Andresen, E. M., Nosek, M. A., & Krahn, G. L. (2007). Response shift theory: Important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(4), 529–536.

Rothrock, N., Hays, R., Spritzer, K., Yount, S., Riley, W., & Cella, D. (2010). Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Multiple chronic conditions—A strategic framework: Optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Boyd, C. M., & Fortin, M. (2010). Future of multimorbidity research: How should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Reviews, 32(2), 451–474.

Acknowledgments

Barile and Luncheon were supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an agreement between the US Department of Energy and CDC. Cella was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to the PROMIS Statistical Center (U54AR057951-02). We would like to thank Adam Burns and Bill Pollard of Porter Novelli for reviewing drafts of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not report any conflicts of interest with presenting these findings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barile, J.P., Reeve, B.B., Smith, A.W. et al. Monitoring population health for Healthy People 2020: evaluation of the NIH PROMIS® Global Health, CDC Healthy Days, and satisfaction with life instruments. Qual Life Res 22, 1201–1211 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0246-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0246-z