Abstract

Background

Capability well-being captures well-being based on people’s ability to do the things they value in life. So far, no capability well-being measures have been validated in dermatological patients.

Objectives

To validate the adult version of the ICEpop CAPability measure (ICECAP-A) in patients with dermatological conditions. We aimed to test floor and ceiling effects, structural, convergent and known-group validity, and measurement invariance.

Methods

In 2020, an online, cross-sectional survey was carried out in Hungary. Respondents with self-reported physician-diagnosed dermatological conditions completed the ICECAP-A, Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), WHO-5 Well-Being Index and two dermatology-specific measures, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Skindex-16.

Results

618 respondents (mean age 51 years) self-reported a physician-diagnosed dermatological condition, with warts, eczema, onychomycosis, acne and psoriasis being the most common. ICECAP-A performed well with no floor and mild ceiling effects. The violation of local independence assumption was found between the attributes of ‘attachment’ and ‘enjoyment’. ICECAP-A index scores correlated strongly with SWLS and WHO-5 (rs = 0.597–0.644) and weakly with DLQI and Skindex-16 (rs = − 0.233 to − 0.292). ICECAP-A was able to distinguish between subsets of patients defined by education and income level, marital, employment and health status. Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis indicated measurement invariance across most of these subgroups.

Conclusions

This is the first study to validate a capability well-being measure in patients with dermatological conditions. The ICECAP-A was found to be a valid tool to assess capability well-being in dermatological patients. Future work is recommended to test measurement properties of ICECAP-A in chronic inflammatory skin conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dermatological conditions are estimated to contribute to approximately 2% to the global burden of disease expressed in disability-adjusted life years, with dermatitis, including atopic, contact and seborrheic dermatitis, acne vulgaris, urticaria, psoriasis, viral and fungal skin diseases being responsible for the largest burden [1]. The adverse effect of skin diseases on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is well-documented [2, 3]. A variety of disease-specific (e.g. Psoriasis Disability Index, Quality of Life Index for Atopic Dermatitis), skin-specific (e.g. Dermatology Life Quality Index, Skindex instrument family) and generic instruments (e.g. EQ-5D, Short-form 36) are used to assess HRQoL in dermatological patients [4]. In addition to HRQoL impact, many dermatological conditions have potential well-being implications for patients. In most societies, attractive and healthy appearance has a particular importance; thus, visible disorders of the skin, hair and nails may create a considerable psychological and social burden that extends beyond health [5]. For example, patients with chronic skin diseases often report to experience lower autonomy, personal growth, life satisfaction, happiness and purpose in life [6, 7].

HRQoL measures may not be able to capture the well-being burden of living with a dermatological disease. Relatively few studies have so far examined the subjective well-being of dermatological patients [7,8,9,10], and none of them have investigated capability well-being. The capability approach, drawing on the work of Nobel Laureate economist Amartya Sen, addresses well-being in terms of people’s capabilities that reflect what people are able to do rather than what they actually do (i.e. functioning) [11]. So far, 14 different capability-based well-being questionnaires have been developed for use in healthcare, such as the ICEpop CAPability Measure (ICECAP), Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit (ASCOT) and Oxford Capability questionnaire-Mental Health (OxCAP-MH) [12, 13]. Over the past decade, these questionnaires have been gaining increasing interest, especially because they may expand the evaluative space in health economic evaluations by allowing to value non-health attributes [12, 13]. In some countries, such as the UK and the Netherlands, health technology assessment bodies recommend the inclusion of capability outcomes in the assessment of health interventions and programmes where the intended benefits from interventions are associated with non-health-related effects (e.g. social or long-term care) [14, 15].

The ICECAP instruments are among the most frequently used capability well-being measures [13]. Previous studies have validated the adult (ICECAP-A) and elderly (ICECAP-O) versions in several mental illnesses, including depression and drug addiction [16,17,18]; however, little empirical evidence is available on their measurement properties in the context of physical problems [19,20,21,22]. So far, the ICECAP measures or other capability-based well-being measures have not been validated in patients with dermatological conditions.

The objective of this study is to validate the ICECAP-A questionnaire in patients with dermatological conditions. We aim to test floor and ceiling effects, structural, convergent and known-group validity and measurement invariance of the ICECAP-A.

Methods

Study population

The study received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Council in Hungary (Reference No. 3857-4/2019/EKU). In February 2020, an internet-based cross-sectional survey was carried out among the general population aged 18 years or over in Hungary. The survey population was recruited from members of an online panel by a survey company using non-probability quota sampling. The online panel had over 150 thousand members who had voluntarily registered to complete surveys in return for earning survey points that could be later redeemed to various rewards (e.g. gift card, prizes). We aimed for representativeness of the Hungarian general public with respect to age, sex, education, place of living and region. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent at the beginning of the survey. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for observational studies [23].

Questionnaire

A self-administered questionnaire was developed for the survey that recorded information about the presence of dermatological conditions, sociodemographic characteristics, health status, HRQoL and well-being. General health status was measured in two separate questions. First, we used a 0–100 horizontal VAS, with 0 being the ‘worst imaginable health’ and 100 being the ‘best imaginable health’. This scale is widely used to measure health status and demonstrated a good validity and excellent reliability [24]. Secondly, we asked respondents to rate their overall health as very good, good, fair, bad or very bad.

Respondents were queried about the presence of any dermatological conditions in two steps. In the first step, they were asked to indicate if they had any dermatological condition at the time of the survey. For this question, a predefined list of ten dermatological disease categories (acne, basal cell carcinoma, eczema, herpes zoster, onychomycosis, psoriasis, rosacea, tinea pedis, urticaria and warts) and an ‘Other’ response option with an open-ended text box were provided to the respondents. In the second step, subjects that self-reported any dermatological condition were asked to mark those conditions that were diagnosed by a physician. There was no missing data in this survey, as participants could only proceed to the next question if they had responded to the previous one.

Outcome measures

ICECAP-A

ICECAP-A is a measure of capability well-being consisting of the following five attributes: stability (an ability to feel settled and secure), attachment (an ability to have love, friendship and support), autonomy (an ability to be independent), achievement (an ability to achieve and progress in life) and enjoyment (an ability to experience enjoyment and pleasure) [25]. The Hungarian version of ICECAP-A has earlier been validated in a general population sample [26]. We used a value set based on general population preferences in the UK to compute ICECAP-A index scores [27]. These values are anchored on a zero (no capability on any attribute) to one (full capability on all attributes) scale.

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)

DLQI is a skin-specific HRQoL questionnaire consisting of 10 items [28]. It aims to capture the impact of dermatological conditions on the patients’ life over the last week. Each item has four or five possible response options that are scored from 0 (‘not at all’ or ‘not relevant’) to 3 (‘very much’). The scores of individual items are summed to generate a total DLQI score that ranges between 0 (no impact on HRQoL) and 30 (maximum HRQoL impact).

Skindex-16

Similarly to the DLQI, Skindex-16 is also a skin-specific HRQoL measure with a one-week recall period [29]. It has 16 individual items that are scored on a continuous bipolar scale with seven boxes anchored by the words ‘never bothered’ (= 0) and ‘always bothered’ (= 6). Responses to the items of Skindex-16 are categorised into three subscales: symptoms, emotions and functioning. Subscale scores are normalized to a 0–100 scale, where higher scores indicate worse HRQoL.

Well-being, life satisfaction and happiness

The 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) was administered to measure subjective well-being over the last two weeks [30, 31]. It asks respondents to rate five positively phrased statements on a 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time) scale, so that the final score ranges between 0 and 25. However, this is conventionally transformed to a 0–100 scale, where higher values indicate greater level of well-being. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used to assess cognitive judgements of one’s life satisfaction [32]. Respondents were asked to indicate their degree of agreement on five items using a seven-point agreement scale with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Total scores for this scale range from 5 to 35 with higher scores suggesting a higher life satisfaction. Furthermore, respondents rated their level of satisfaction with life (SWL) on an 11-point numeric rating scale with endpoints of ‘not satisfied at all’ (= 0) and ‘completely satisfied’ (= 10). A similar numeric scale was used to assess happiness with endpoints of ‘completely unhappy’ (= 0) and ‘completely happy’ (= 10).

Statistical analyses

Most of our analyses concerned with measurement properties that are relevant in the context of a measure to be used in economic evaluation [33]. These included floor and ceiling effects, structural, convergent and known-group validity and measurement invariance. Most of these measurement properties have been tested in previous ICECAP-A and ICECAP-O validation studies in general population and patient samples [16, 17].

Floor and ceiling effects

Descriptive statistics were used to provide an overview of the study population. Floor and ceiling effects were considered present if more than 15% of the respondents scored the worst and best capability level for attributes, or zero or one on ICECAP-A index, respectively [34].

Structural validity

Confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to confirm the factor structure of ICECAP-A. Model fit was tested using multiple criteria: χ2-statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) with values of a p < 0.05 for the χ2-statistic, CFI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 as an indication of good fit [35].

Convergent validity

We tested convergent validity for each ICECAP-A attribute as well as the index scores by using Spearman’s rank-order correlations. Correlation coefficients (rs) were considered very weak if < 0.20, weak if 0.20–0.39, moderate if 0.40–0.59 and strong if ≥ 0.60 [36]. We expected strong correlations with life satisfaction measures (SWLS and SWL) [37], moderate correlations with health status VAS [13, 20, 22, 37] and subjective well-being as assessed by the WHO-5 [26] and happiness [38], and weak correlations with skin-specific HRQoL measures (DLQI and Skindex-16) [22].

Known-group validity

Known-group validity was assessed by examining the extent to which the ICECAP-A was able to distinguish between groups of respondents differing in a characteristic that was likely to be associated with capability well-being. We hypothesized no associations between capability scores and age or sex, and positive associations of capabilities with better self-perceived health status, being more educated, being married or living in a domestic partnership, being employed and having a higher income level [22, 26, 37, 38]. The differences in median ICECAP-A scores across groups were tested by Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal Wallis H test.

Measurement invariance

Measurement invariance of the ICECAP-A across different subgroups [sex, age (< 65 years vs. ≥ 65 years), level of education, marital status, income and DLQI score (DLQI ≤ 10 vs. DLQI > 10)] was evaluated using multigroup confirmatory factor analysis [39]. DLQI score was split at ten points as DLQI > 10 is considered a ‘very large impact’ of the dermatological condition on patients’ lives [40]. A sequence of configural (i.e. same pattern of factors), metric (i.e. same pattern of factors and loadings) and scalar (i.e. same pattern of factors, loadings and item thresholds) models were tested for each variable. We first examined the fit of the configural model. For the assessment of model fit, χ2-statistic, TLI, CFI and RMSEA were used. We compared the fit of the unconstrained configural model to the metric model, and then, the metric model to the most constrained scalar model. A decrease in CFI ≤ 0.01 was considered as an evidence for invariance [41]. All the statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS 25.0 and Amos 25.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY) for the data analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

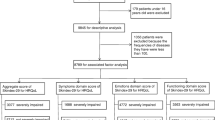

A total of 3873 people opened the questionnaire, 60 individuals did not consent to the study, 1354 did not finish it and 458 did not meet the quotas, resulting in a final sample of 2001 respondents (Fig. 1). Of the 2001 respondents, 618 individuals self-reported a dermatological condition diagnosed by a physician, and thus, formed the analytical sample for this study. The majority of the sample was female (57.9%), and the mean age was 50.5 ± 16.9 years (Table 1). The most common dermatological conditions in the sample were warts (23.1%), eczema (22.7%), onychomycosis (18.3%), acne (13.4%), psoriasis (13.3%), tinea pedis (7.4%), basal cell carcinoma (5.0%), rosacea (5.0%), urticaria (3.6%), herpes zoster (1.6%) and other (16.5%) (the presence of multiple diseases in one individual was possible). Responses for the open-ended ‘other dermatological condition’ category are presented in Online resource 1.

Health status, HRQoL and well-being

Patients assessed their general health status to a mean of 66.54 ± 23.35 using a 0–100 VAS, ranging from 51.42 in herpes zoster to 68.75 in acne (Fig. 2). The proportion of patients with ‘very good’ or ‘good’ self-reported health status was 37.5%, while 42.7% indicated ‘fair’ and 19.9% ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. The mean DLQI score in the sample was 3.76 ± 5.03 (Table 2). More problems were reported on the emotions subscale of Skindex-16 (35.92 ± 30.38) compared with symptoms (29.98 ± 28.62) and functioning (22.15 ± 28.31). The mean SWLS, SWL, WHO-5 and happiness scores were 20.08 ± 6.75, 5.93 ± 2.39, 49.69 ± 19.94 and 6.11 ± 2.45, respectively.

Capability well-being outcomes

Approximately half of patients recorded responses on the two lowest levels of capability for stability (52.1%) and achievement (49.7%) of ICECAP-A (Fig. 3). The largest proportion of responses in the lowest level was observed for stability (‘I am unable to feel settled and secure in any areas of my life’, 10.0%). Over two-thirds of patients reported no or mild limitations (highest two levels on ICECAP-A) in their capabilities for the attachment (i.e. love friendship, support), autonomy (i.e. being independent) and enjoyment (i.e. enjoyment and pleasure) attributes. The mean ICECAP-A index score was 0.69 ± 0.20, ranging from 0.61 in herpes zoster to 0.76 in basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 2). The impact of various dermatological conditions on health and capability differed; certain conditions (e.g. herpes zoster) had a large effect on both health and capabilities, while others (e.g. acne, eczema) mostly affected capabilities. Mean ICECAP-A index scores of patients with a DLQI ≤ 10 and DLQI > 10 were 0.70 ± 0.19 and 0.61 ± 0.23, respectively (p = 0.002).

Measurement properties of ICECAP-A

Floor and ceiling effects

No floor effects were detected for any of the five attributes. Ceiling effects were apparent for the attributes of attachment (23.0%), autonomy (17.6%) and enjoyment (18.6%) (Fig. 3). Five (0.8%) patients reported full capability and four (0.7%) patients were in ‘no capability’; thus, there were no ceiling or floor effects for the index scores.

Structural validity

A one-factor model was established in confirmatory factor analysis with the following goodness-of-fit indices: χ2 = 35.55 (p < 0.001), RMSEA = 0.100, TLI = 0.935 and CFI = 0.968. A covariance between the error terms (i.e. local dependency) was identified between the attributes of attachment and enjoyment that improved the model fit [χ2 = 10.18 (p = 0.037), RMSEA = 0.050, TLI = 0.984 and CFI = 0.993] (Fig. 4).

Convergent validity

Most hypotheses regarding convergent validity were met. The ICECAP-A index showed a strong correlation with SWLS, SWL, WHO-5 and happiness scores (rs = 0.597–0.689) (Table 3). A moderate or strong correlation was found between these four outcomes and all ICECAP-A attributes with the exception of autonomy (rs = 0.281–0.607). General health status VAS exhibited a moderate correlation with the ICECAP-A index and weak correlation with the five attributes (rs = 0.233–0.449). DLQI and the three Skindex-16 subscales were weakly or very weakly correlated with all five ICECAP-A attributes and index score (rs = − 0.123 to − 0.292).

Known-group validity

All our hypotheses with respect to validity between known groups of patients were confirmed. Patients with worse self-perceived health status, lower level of education, those not being married or living in domestic partnership, unemployed or with lower income were associated with significantly lower levels of capability-well-being (Table 1). As expected, there were no significant associations between age or sex and ICECAP-A index scores.

Measurement invariance

Configural and metric measurement invariance were supported (ΔCFI ≤ 0.01) across all subgroups of patients defined by sex, age, level of education, being married/living in a domestic partnership, income, self-perceived health status and HRQoL as assessed by the DLQI (Table 4). The scalar invariance model demonstrated a slight deterioration in model fit, but only for age, marital status and DLQI groups.

Discussion

In prior studies, patients with chronic skin diseases, such as psoriasis, pemphigus and morphea, were more likely to be associated with decreased subjective well-being, happiness and life satisfaction [7,8,9, 42,43,44]. Yet this is the first study to validate a capability well-being instrument in dermatological patients. Corroborating with previous research on the validity of ICECAP-A in other clinical and population-based studies [16], our findings provide mostly favourable evidence on the psychometric properties of ICECAP-A in a dermatological patient population, including no floor effect, good convergent and known-group validity and established metric and configural invariance across subgroups of patients. However, a mild ceiling effect was present for three attributes, and a local dependence was identified between two of the five attributes.

The sample used for this study was large and heterogeneous representing the most common dermatological conditions in the population, such as warts, eczema, onychomycosis, acne, psoriasis and tinea pedis, among others. There are no data available on the precise prevalence of most dermatological conditions in Hungary. Few existing prevalence estimates from Hungary or the Central and Eastern European region include adult psoriasis (Central Europe: range 0.62–5.32%) and atopic eczema (5%) [45, 46]. In our study, the number of patients with psoriasis and eczema (a wider category than atopic eczema) in the total sample (n = 2001) was 82 (4.1%) and 141 (7.0%), respectively, suggesting a good overall representativeness.

Approximately half of the sample reported severe limitations in their stability (feeling settled and secure) and achievement and progress. Mean ICECAP-A index (0.69) was found to be considerably lower than previously reported in other clinical groups (e.g. spinal cord injury 0.76 [37], arthritis 0.81 [47], asthma 0.84 [47], lower urinary tract symptoms 0.85 [22], knee pain 0.89 [21]); but somewhat higher than in patients with opiate dependence (0.66) [48] or depression (0.64) [18]. Moreover, < 1% experienced full capability with regard to all five attributes of ICECAP-A that was 3% and 12% in patients with spinal cord injury and lower urinary tract symptoms, respectively [22, 37]. However, comparison of these scores might be limited by the different language versions of ICECAP-A used in the studies and possible cross-cultural and condition-specific differences in the interpretation of the attributes.

Attributes of ICECAP-A were developed to capture five independent and distinct concepts, three of which, ‘attachment’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘enjoyment’ were aimed to be close equivalents to ‘emotions’, ‘control’ and ‘play’ from Nussbaum’s list of central human capabilities [25]. Notwithstanding, we found the violation of local independence between the attributes of attachment (an ability to have love, friendship and support) and enjoyment (ability to experience enjoyment and pleasure) suggesting an overlap in the content of the attributes. This is not surprising as during the development of the ICECAP-A, the attribute of attachment was reported to be strongly related to the interactions with other people, including partner, close family and good friends, and being around other people may also be a major source of enjoyment and pleasure in life [25, 38].

The ICECAP-A was able to differentiate between 6 of 8 predefined known groups of patients. Higher education and income level, being married or living in a domestic partnership, and better self-perceived general health status or skin-specific HRQoL were associated with higher capability levels, while unemployed patients scored lower on ICECAP-A. The positive associations between higher ICECAP-A scores and marital status, labour force participation and better general health status have earlier been confirmed in patients with type 2 diabetes and spinal cord injury [19, 37]. Evidence is less conclusive with regard to the association of age and ICECAP-A scores. Three earlier studies among members of the general population and female patients with urinary incontinence reported the lack of association between age and ICECAP-A scores [22, 25, 26], whereas another study identified a clear trend towards lower ICECAP-A scores with older age in patients with type 2 diabetes [19].

The measurement equivalence found in this study highlights that ICECAP-A scores can be reliably compared across most known groups of patients. However, scalar equivalence was not confirmed for all subgroups suggesting that certain groups (e.g. being married/living in a domestic partnership or not, DLQI ≤ 10 and DLQI > 10) tend to interpret the attributes of the ICECAP-A in a different way, and differences in scores between these groups are suggested to be treated with caution.

The weak correlation of the ICECAP-A with DLQI and Skindex-16 confirmed that capability wellbeing is a different, but complement construct to HRQoL. It has been increasingly argued to look at outcomes other than health ones, including subjective well-being and capabilities [11, 49, 50]. In addition to health gains, health interventions may offer capability gains too that can represent additional treatment benefits. Health economists and policymakers in healthcare may also see this compelling as adopting the capability wellbeing perspective has already demonstrated to result in different cost-effectiveness estimates, and thus, treatment recommendations for certain health interventions [51, 52]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK has already recommended the ICECAP-A and its elderly version, the ICECAP-O questionnaires in its reference case for evaluating social care interventions [15].

Strengths of this study are the large and heterogeneous patient sample and the survey design that ensured a broad representation of the general population. A further strength is the use of validated skin-specific HRQoL measures, such as the DLQI and Skindex-16. To our knowledge, we are the first to test measurement invariance for the ICECAP-A. There are some limitations that are worth noting. First, disadvantages of the online data collection, such as excluding people with no internet access should be considered. In Hungary among the population 16 years or older, the average internet penetration rate at the time of this survey was around 80% [53]. Thus, selection bias might have occurred, to some extent. Secondly, the study was based on self-reported information on diagnosis provided by patients that may be more prone to errors compared to data collection in clinical settings, whereby diagnosis is confirmed by physicians. Thirdly, the survey reached mostly less severe cases as 89.3% had a DLQI score of ≤ 10. Furthermore, we did not have any information on the treatment history of these patients. Several earlier studies from Hungary confirmed that successful treatment and management of skin diseases improve health-related quality of life and well-being of patients [9, 54,55,56,57,58,59]. Fourthly, in absence of a Hungarian value set for the ICECAP-A, our analyses relied on the ICECAP-A value set for the UK and not that of the Hungarian population, whose values may differ across attributes and levels. Finally, this study had a cross-sectional design that prevented the assessment of other measurement properties, such as test–retest reliability and responsiveness.

In conclusion, the ICECAP-A was found to be a valid tool to measure capability well-being in a dermatological patient population. However, a local dependency was found between the attributes of ‘attachment’ and ‘enjoyment’ that warrants further investigation. Future studies are recommended to assess capability well-being and confirm measurement properties of the ICECAP-A in common chronic inflammatory skin diseases, such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis and acne. Further research steps also include the validation of the elderly version of ICECAP, the ICECAP-O in dermatological patients as well as the validation of alternative capability measures in this patient population.

Data availability

All data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Karimkhani, C., Dellavalle, R. P., Coffeng, L. E., Flohr, C., Hay, R. J., Langan, S. M., et al. (2017). Global skin disease morbidity and mortality: An update from the global burden of disease study 2013. JAMA Dermatology, 153(5), 406–412.

Finlay, A. Y., Chernyshov, P. V., Tomas Aragones, L., Bewley, A., Svensson, A., Manolache, L., et al. (2021). Methods to improve quality of life, beyond medicines. Position statement of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Force on Quality of Life and Patient Oriented Outcomes. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 35(2), 318–328.

Finlay, A. Y., Salek, M. S., Abeni, D., Tomás-Aragonés, L., van Cranenburgh, O. D., Evers, A. W., et al. (2017). Why quality of life measurement is important in dermatology clinical practice: An expert-based opinion statement by the EADV Task Force on Quality of Life. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 31(3), 424–431.

Both, H., Essink-Bot, M. L., Busschbach, J., & Nijsten, T. (2007). Critical review of generic and dermatology-specific health-related quality of life instruments. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 127(12), 2726–2739.

Rumsey, N. (2018). Psychosocial adjustment to skin conditions resulting in visible difference (disfigurement): What do we know? Why don’t we know more? How shall we move forward? International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, 4(1), 2–7.

Offidani, E., Del Basso, D., Prignago, F., & Tomba, E. (2016). Discriminating the presence of psychological distress in patients suffering from psoriasis: An application of the clinimetric approach in dermatology. Acta Dermato Venereologica, 96(217), 69–73.

Schuster, B., Ziehfreund, S., Albrecht, H., Spinner, C. D., Biedermann, T., Peifer, C., et al. (2020). Happiness in dermatology: A holistic evaluation of the mental burden of skin diseases. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 34(6), 1331–1339.

Liu, L., Li, S., Zhao, Y., Zhang, J., & Chen, G. (2018). Health state utilities and subjective well-being among psoriasis vulgaris patients in mainland China. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1323–1333.

Mitev, A., Rencz, F., Tamási, B., Hajdu, K., Péntek, M., Gulácsi, L., et al. (2019). Subjective well-being in patients with pemphigus: A path analysis. The European Journal of Health Economics, 20(Suppl 1), 101–107.

Pilch, M., Scharf, S. N., Lukanz, M., Wutte, N. J., Fink-Puches, R., Glawischnig-Goschnik, M., et al. (2016). Spiritual well-being and coping in scleroderma, lupus erythematosus, and melanoma. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 14(7), 717–728.

Sen, A. (1987). Commodities and capabilities. Oxford University Press.

Makai, P., Brouwer, W. B., Koopmanschap, M. A., Stolk, E. A., & Nieboer, A. P. (2014). Quality of life instruments for economic evaluations in health and social care for older people: A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 102, 83–93.

Helter, T. M., Coast, J., Łaszewska, A., Stamm, T., & Simon, J. (2020). Capability instruments in economic evaluations of health-related interventions: A comparative review of the literature. Quality of Life Research, 29(6), 1433–1464.

Zorginstituut Nederland. (2016). Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare. Available from https://english.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publications/reports/2016/06/16/guideline-for-economic-evaluations-in-healthcare. Accessed on December 9, 2020.

National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE). Developing NICE guidelines: The manual. Process and methods [PMG20]. Last updated: 15 Oct 2020. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/chapter/incorporating-economic-evaluation Accessed on December 9, 2020.

Afentou, N., & Kinghorn, P. (2020). A systematic review of the feasibility and psychometric properties of the ICEpop CAPability measure for adults and its use so far in economic evaluation. Value Health, 23(4), 515–526.

Proud, L., McLoughlin, C., & Kinghorn, P. (2019). ICECAP-O, the current state of play: A systematic review of studies reporting the psychometric properties and use of the instrument over the decade since its publication. Quality of Life Research, 28(6), 1429–1439.

Mitchell, P. M., Al-Janabi, H., Byford, S., Kuyken, W., Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., et al. (2017). Assessing the validity of the ICECAP-A capability measure for adults with depression. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 46.

Xiong, Y., Wu, H., & Xu, J. (2021). Assessing the reliability and validity of the ICECAP-A instrument in Chinese type 2 diabetes patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 5.

Keeley, T., Al-Janabi, H., Nicholls, E., Foster, N. E., Jowett, S., & Coast, J. (2015). A longitudinal assessment of the responsiveness of the ICECAP-A in a randomised controlled trial of a knee pain intervention. Quality of Life Research, 24(10), 2319–2331.

Keeley, T., Coast, J., Nicholls, E., Foster, N. E., Jowett, S., & Al-Janabi, H. (2016). An analysis of the complementarity of ICECAP-A and EQ-5D-3 L in an adult population of patients with knee pain. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14, 36.

Goranitis, I., Coast, J., Al-Janabi, H., Latthe, P., & Roberts, T. E. (2016). The validity and responsiveness of the ICECAP-A capability-well-being measure in women with irritative lower urinary tract symptoms. Quality of Life Research, 25(8), 2063–2075.

von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349.

de Boer, A. G., van Lanschot, J. J., Stalmeier, P. F., van Sandick, J. W., Hulscher, J. B., de Haes, J. C., et al. (2004). Is a single-item visual analogue scale as valid, reliable and responsive as multi-item scales in measuring quality of life? Quality of Life Research, 13(2), 311–320.

Al-Janabi, H., Flynn, T. N., & Coast, J. (2012). Development of a self-report measure of capability wellbeing for adults: The ICECAP-A. Quality of Life Research, 21(1), 167–176.

Baji, P., Farkas, M., Dobos, Á., Zrubka, Z., Gulácsi, L., Brodszky, V., et al. (2020). Capability of well-being: Validation of the Hungarian version of the ICECAP-A and ICECAP-O questionnaires and population normative data. Quality of Life Research, 29(10), 2863–2874.

Flynn, T. N., Huynh, E., Peters, T. J., Al-Janabi, H., Clemens, S., Moody, A., et al. (2015). Scoring the ICECAP-A capability instrument. Estimation of a UK general population tariff. Health Economics, 24(3), 258–269.

Finlay, A. Y., & Khan, G. K. (1994). Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—A simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 19(3), 210–216.

Chren, M.-M., Lasek, R. J., Sahay, A. P., & Sands, L. P. (2001). Measurement properties of Skindex-16: A brief Quality-of-Life measure for patients with skin diseases. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, 5(2), 105–110.

Topp, C. W., Østergaard, SD., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84, 167–176.

Staehr Johansen, K. (1998). The use of well-being measures in primary health care—The Dep-Care Project, in World Health organization, regional office for Europe: well-being measures in primary health care—The DepCare Project. Geneva: World Health Organization, E60246.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Brazier, J., & Deverill, M. (1999). A checklist for judging preference-based measures of health related quality of life: Learning from psychometrics. Health Economics, 8(1), 41–51.

Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., et al. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Swinscow, T. D. V., & Campbell, M. J. (2002). Statistics at square one. BMJ.

Mah, C., Noonan, V. K., Bryan, S., & Whitehurst, D. G. (2020). Empirical validity of a generic, preference-based capability wellbeing instrument (ICECAP-A) in the context of spinal cord injury. The Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00451-6

Al-Janabi, H., Peters, T. J., Brazier, J., Bryan, S., Flynn, T. N., Clemens, S., et al. (2013). An investigation of the construct validity of the ICECAP-A capability measure. Quality of Life Research, 22(7), 1831–1840.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70.

Finlay, A. Y. (2005). Current severe psoriasis and the rule of tens. British Journal of Dermatology, 152(5), 861–867.

Reise, S. P., & Waller, N. G. (2009). Item response theory and clinical measurement. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 27–48.

Eskin, M., Savk, E., Uslu, M., & Küçükaydoğan, N. (2014). Social problem-solving, perceived stress, negative life events, depression and life satisfaction in psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 28(11), 1553–1559.

Solovan, C., Marcu, M., & Chiticariu, E. (2014). Life satisfaction and beliefs about self and the world in patients with psoriasis: A brief assessment. European Journal of Dermatology, 24(2), 242–247.

Szramka-Pawlak, B., Dańczak-Pazdrowska, A., Rzepa, T., Szewczyk, A., Sadowska-Przytocka, A., & Zaba, R. (2014). Quality of life and optimism in patients with morphea. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9(4), 863–870.

Kowalska-Olędzka, E., Czarnecka, M., & Baran, A. (2019). Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in Europe. Journal of Drug Assessment, 8(1), 126–128.

Parisi, R., Iskandar, I. Y. K., Kontopantelis, E., Augustin, M., Griffiths, C. E. M., & Ashcroft, D. M. (2020). National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: Systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ, 369, m1590.

Mitchell, P. M., Al-Janabi, H., Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., & Coast, J. (2015). The relative impacts of disease on health status and capability wellbeing: A multi-country study. PloS ONE, 10(12), e0143590.

Peak, J., Goranitis, I., Day, E., Copello, A., Freemantle, N., & Frew, E. (2018). Predicting health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-5 L) and capability wellbeing (ICECAP-A) in the context of opiate dependence using routine clinical outcome measures: CORE-OM, LDQ and TOP. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 106.

Dolan, P., & Kahneman, D. (2008). Interpretations of utility and their implications for the valuation of health. The Economic Journal, 118(525), 215–234.

Sen, A. (1993). Capability and well-being. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 30–53). Oxford University Press.

Makai, P., Looman, W., Adang, E., Melis, R., Stolk, E., & Fabbricotti, I. (2015). Cost-effectiveness of integrated care in frail elderly using the ICECAP-O and EQ-5D: Does choice of instrument matter? The European Journal of Health Economics, 16(4), 437–450.

Goranitis, I., Coast, J., Day, E., Copello, A., Freemantle, N., & Frew, E. (2017). Maximizing health or sufficient capability in economic evaluation? A methodological experiment of treatment for drug addiction. Medical Decision Making, 37(5), 498–511.

Hungarian Central Statistical Office. (2019). Internet penetration rate in 2019. Available from https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xstadat/xstadat_eves/i_int078b.html. Accessed on March 8, 2021.

Bali, G., Kárpáti, S., Sárdy, M., Brodszky, V., Hidvégi, B., & Rencz, F. (2018). Association between quality of life and clinical characteristics in patients with morphea. Quality of Life Research, 27(10), 2525–2532.

Bató, A., Brodszky, V., Gergely, L. H., Gáspár, K., Wikonkál, N., Kinyó, Á., et al. (2021). The measurement performance of the EQ-5D-5L versus EQ-5D-3L in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Quality of Life Research, 30(5), 1477–1490.

Gergely, L. H., Gáspár, K., Brodszky, V., Kinyó, Á., Szegedi, A., Remenyik, É., et al. (2020). Validity of EQ-5D-5L, Skindex-16, DLQI and DLQI-R in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 34(11), 2584–2592.

Rencz, F., Poór, A. K., Péntek, M., Holló, P., Kárpáti, S., Gulácsi, L., et al. (2018). A detailed analysis of ‘not relevant’ responses on the DLQI in psoriasis: Potential biases in treatment decisions. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 32(5), 783–790.

Rencz, F., Mitev, A. Z., Szabó, Á., Beretzky, Z., Poór, A. K., Holló, P., et al. (2021). A Rasch model analysis of two interpretations of “not relevant” responses on the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Quality of Life Research, 30, 2375.

Tamási, B., Brodszky, V., Péntek, M., Gulácsi, L., Hajdu, K., Sárdy, M., et al. (2019). Validity of the EQ-5D in patients with pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. British Journal of Dermatology, 180(4), 802–809.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following individuals for their support in designing the questionnaire (László Gulácsi and Márta Péntek) and database management (Ákos Szabó).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Corvinus University of Budapest. This study has been supported by the Higher Education Institutional Excellence Program of the Ministry of Innovation and Technology in the framework of the Financial and Public Services research Project (NKFIH-1163-10/2019). This publication was supported by the Higher Education Institutional Excellence Program 2020 of the Ministry of Innovation and Technology in the framework of the 'Financial and Public Services' research Project (TKP2020-IKA-02) at the Corvinus University of Budapest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript. Data analysis was performed by FR, AZM and BJ. The manuscript was drafted by FR. Funding was obtained by VB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

F.R., A.Z.M. and B.J. received a grant support in connection to writing this article from the Higher Education Institutional Excellence Program 2020 of the Ministry of Innovation and Technology in the framework of the ‘Financial and Public Services’ research Project (TKP2020-IKA-02) at the Corvinus University of Budapest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Council in Hungary (Reference No. 3857-4/2019/EKU).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rencz, F., Mitev, A.Z., Jenei, B. et al. Measurement properties of the ICECAP-A capability well-being instrument among dermatological patients. Qual Life Res 31, 903–915 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02967-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02967-2