Abstract

Background

To assess the criterion and construct validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 well-being and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) score, a short version of the KIDSCREEN-52 and KIDSCREEN-27 instruments.

Methods

The child self-report and parent report versions of the KIDSCREEN-10 were tested in a sample of 22,830 European children and adolescents aged 8–18 and their parents (n = 16,237). Correlation with the KIDSCREEN-52 and associations with other generic HRQoL measures, physical and mental health, and socioeconomic status were examined. Score differences by age, gender, and country were investigated.

Results

Correlations between the 10-item KIDSCREEN score and KIDSCREEN-52 scales ranged from r = 0.24 to 0.72 (r = 0.27–0.72) for the self-report version (proxy-report version). Coefficients below r = 0.5 were observed for the KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions Financial Resources and Being Bullied only. Cronbach alpha was 0.82 (0.78), test–retest reliability was ICC = 0.70 (0.67) for the self- (proxy-)report version. Correlations between other children self-completed HRQoL questionnaires and KIDSCREEN-10 ranged from r = 0.43 to r = 0.63 for the KIDSCREEN children self-report and r = 0.22–0.40 for the KIDSCREEN parent proxy report. Known group differences in HRQoL between physically/mentally healthy and ill children were observed in the KIDSCREEN-10 self and proxy scores. Associations with self-reported psychosomatic complaints were r = −0.52 (−0.36) for the KIDSCREEN-10 self-report (proxy-report). Statistically significant differences in KIDSCREEN-10 self and proxy scores were found by socioeconomic status, age, and gender.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the KIDSCREEN-10 provides a valid measure of a general HRQoL factor in children and adolescents, but the instrument does not represent well most of the single dimensions of the original KIDSCREEN-52. Test–retest reliability was slightly below a priori defined thresholds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) refers to an individual’s perception and subjective evaluation of their health and well-being within their unique cultural environment [1]. Generic questionnaires for children and adolescents can be useful in identifying subgroups of children and adolescents who are at risk for health problems, and can assist in determining the burden of a particular disease or disability [2]. Assessing the HRQoL of children and adolescents could also help to detect hidden morbidity and health care needs which are not identified using traditional medical indicators [3, 4]. Although it is important to obtain responses via self-reports whenever possible, this may not be practicable in very young children or children with developmental delay or mental retardation [5]. In that case, HRQoL may only be ascertained via proxy (parent) reports.

The generic KIDSCREEN-52 HRQoL questionnaire [6] was the first HRQoL instrument for children and adolescents and their parents, which was developed simultaneously in several different countries. It was tested in a large representative sample of children and adolescents [7], thereby helping to provide a broad perspective on the understanding and interpretation of HRQoL across different countries.

A shorter version was then developed, which contained 27 items distributed in 5 dimensions [8, 9]. Both the KIDSCREEN-52 and the KIDSCREEN-27 were shown to meet the criteria of a properly defined concept to be measured, high reliability, good validity, meaningful interpretability, low burden, alternative means of administration (self-/proxy report, paper–pencil, computerized), and appropriate cultural adaptations as proposed by the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcome Trust for the evaluation of Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) instruments [10]. However, an even shorter HRQoL questionnaire would be useful in public health and clinical studies such as large-scaled population-based studies, routine monitoring and screening and would help to reduce response burden and save administration costs. Furthermore, summarizing scores into a single value can be useful for examining overall changes in HRQoL [11, 12] and is a prerequisite for certain type of health economic studies, where quality of life is to be combined with survival time, so-called quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). [13] Summary score measures can be useful in cases where the association between an aspect like e.g., a particular health condition and the different QoL dimensions point into the same direction. It has been shown that in such a case a summary score can be more effective to assess the impact on QoL [14].

In order to reduce the KIDSCREEN-27 to a short score (the KIDSCREEN-10), item response theory and differential item functioning techniques were used. The way in which the shorter version was developed and the results of analyzing the instrument’s structural and cross-cultural validity are reported in a companion paper [15]. The KIDSCREEN-10 consists of 10 items and provides a Rasch-scaled single score of HRQoL [15, 16]. Both self-report and proxy versions were developed. It was decided to use the KIDSCREEN-27 as a starting point for reduction to ensure that each shorter KIDSCREEN measure is encompassed in all longer versions.

The aim of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the KIDSCREEN-10 self-report and proxy versions, specifically their criterion, convergent, and known groups validity together with their reliability.

Methods

Subjects and settings

The current analyses are based on a pre-existing data set that was used to investigate the psychometric properties of the longer KIDSCREEN-52 and -27 measures [6–9]. The following 13 countries participated in the KIDSCREEN study: Austria (AT), Czech Republic (CZ), France (FR), Germany (DE), Greece (EL), Hungary (HU), Ireland (IE), Poland (PL), Spain (ES), Sweden (SE), Switzerland (CH), the Netherlands (NL), and the United Kingdom (UK). The target population for the KIDSCREEN study was children and adolescents aged 8–18 and their parents. Parent reports were not collected in Sweden and Ireland.

Three approaches to sample selection and administration were followed: (1) telephone sampling followed by mail survey (AT, CH, DE, ES, FR, and NL), (2) school sampling and administration (EL, HU, IE, and SE), or school sampling and mail administration (PL), and (3) multistage random sampling of communities and households (CZ). In the UK, a combination of telephone and school sampling methods was used. Information from parents was not collected in IE and SE. In 11 countries, a retest with a 2-week interval for all participants was performed in random selections of a total of 559 participants.

Fieldwork was carried out between May and September 2003 except in IE, where data were collected in 2005. All procedures were carried out following the data protection requirements of the European Parliament (Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data). Each country was asked to respect ethical and legal requirements in their country for this type of survey and to obtain signed informed consent from participants. A more detailed description of the KIDSCREEN sampling methods is provided elsewhere, together with a detailed analysis on sample representativeness based on Eurostat data [17].

Measures

Children and adolescents filled in a number of HRQOL and other questionnaires in order to be able to assess the psychometric properties of the KIDSCREEN-10. The comprehensive study questionnaire was completed in a single administration. Overall, children had to answer 170 items whereas adolescents and parents had to respond to 200 and 210 items, respectively.

KIDSCREEN-10

The KIDSCREEN-10 score contains 10 items. Each item is answered on a 5-point response scale. The KIDSCREEN-10 Item statements are: (1) Have you felt fit and well? (2) Have you felt full of energy? (3) Have you felt sad? (4) Have you felt lonely? (5) Have you had enough time for yourself? (6) Have you been able to do the things that you want to do in your free time? (7) Have your parent(s) treated you fairly? (8) Have you had fun with your friends? (9) Have you got on well at school? (10) Have you been able to pay attention? Answer categories item 1 and 9: not at all—slightly—moderately—very-extremely. All other items: never—seldom—quite often—very often—always. Items 1 and 2 explore the level of the child’s/adolescent’s physical activity, energy and fitness. Items 3 and 4 cover how much the child/adolescent experiences depressive moods and emotions and stressful feelings. Items 5 and 6 ask about the child’s opportunities to structure and enjoy his/her social and leisure time and participation in social activities. Item 7 explores the quality of the interaction between child/adolescent and parent or carer and the child’s/adolescent’s feelings toward their parents/carers. Item 8 examines the nature of the child’s/adolescent’s relationships with other children/adolescents. Finally, items 9 and 10 explore the child’s/adolescent’s perception of his/her cognitive capacity and satisfaction with school performance. Responses were coded so that higher values indicate better HRQoL; they were then summed and Rasch person parameters (PP) were assigned to each possible sum score. The PPs were transformed into values with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of approximately 10 [7]. A low score indicates a poor HRQOL, and a high score is indicative of a better HRQOL. Both the KIDSCREEN-10 self and proxy report versions were tested in the present study. The proxy report version uses the same items as the self-report version but from a proxy perspective. E.g., the self-report item “Have you felt full of energy?” is mirrored by the proxy report item “Has your child felt full of energy?”.

KIDSCREEN-27

The KIDSCREEN-27 is the middle version of the family of KIDSCREEN measures. It consists of 27 items measuring Physical Well-being, Psychological Well-being, Autonomy and Parent Relations, Peers and Social Support, and School Environment. Interscale correlation range from 0.36 to 0.59 (0.33–0.57) for the self-report (proxy report) [7].

KIDSCREEN-52

The KIDSCREEN-52 is the long version of the family of KIDSCREEN measures. It consists of 52 items measuring Physical Well-being, Psychological Well-being, Moods and Emotions, Self-Perception, Autonomy, Parent Relation and Home Life, Financial Resources, Peers and Social Support, School Environment and Being Bullied. Moderate to high correlation was expected with all KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions except Financial Resources and Being Bullied. Interscale correlation range from 0.30 to 0.62 (0.27–0.61) for the self-report (proxy report). However, the self-report (proxy report) scales Being Bullied and Financial correlated only 0.10–0.40 (0.08–0.37) with the other scales [6, 7].

The KIDSCREEN-52, -27 and -10 measures are designed for children and adolescents aged 8–18 for both child and parent proxy report.

PedsQL

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 Generic child self-reported Core Scales [18] consist of 23 items measuring Physical, Emotional, Social, and School dimensions of HRQoL. The PedsQL was completed by the samples in UK and IE. Moderate to high correlations were expected for KIDSCREEN-10 with PedsQL Psychosocial summary and Total.

CHIP-AE

The Child Health and Illness Profile-Adolescent Edition (CHIP-AE) satisfaction domain is a generic measure of satisfaction with health [19] and was administered to adolescents aged 12 years or older in all countries. A moderate to high correlation was expected between KIDSCREEN-10 and the CHIP-AE Satisfaction domain.

YQOL-S

The Youth Quality of Life Instrument-Surveillance Version (YQOL-S) is a 13-item generic quality of life (QoL) questionnaire, which provides an overall score of self-perceived QOL [20, 21]. The YQOL-S was completed by adolescents aged 12 years and older in all countries. A moderate to high correlation was expected between the KIDSCREEN-10 and YQOL-S Perceptual scale.

HBSC-SCL

The Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Symptom Checklist is a brief screening instrument that asks children and adolescents about the frequency of occurrence of symptoms like headache, stomachache, irritability/bad temper, feeling nervous, etc. [22]. An index score was calculated. All participating countries except IE included the symptom checklist. A moderate to high correlation was expected for KIDSCREEN-10 with the HBSC Symptom Checklist.

CSHCN

The Children with Special Health Care Needs Screener (CSHCN) [23, 24] was included in all participating countries except IE and SE as a measure of physical and general chronic health status. The CSHCN contains five question sequences which address the use or need of prescribed medication; medical, mental health, or educational services; specialized therapies; functional limitations and treatment or counseling for emotional or developmental problems. The items were completed by parents. Responders were classified into cases with and without special health care needs. It was expected that children with special health care needs would score lower on the KIDSCREEN-10. A medium to large effect size was expected for this mean difference [6–8].

SDQ

The Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief screening questionnaire that asks about children’s and teenagers’ symptoms and positive attitudes [25]. The SDQ asks about positive or negative attributes in 20 items regarding emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention and peer relationship problems. A total difficulties score is generated. Using cut-off values provided by the developer of the SDQ [26], children and adolescents were classified as normal, borderline and abnormal. The SDQ was completed by parents. The SDQ was not included in IE and SE. It was expected that children with mental health problems would score lower on the KIDSCREEN-10. A medium to large effect size was expected for this mean difference [6–8].

FAS

The Family Affluence Scale (FAS), a socioeconomic indicator to be filled in by children, includes family car ownership, having own unshared room, the number of computers at home, and times the child spent on holidays in the past 12 months. The cross-cultural validity of the FAS has been shown in multinational surveys across 27 and 35 countries [27]. The FAS was collected in eight categories ranging from 0 to 7, which were recoded into 3 groups in the analysis (low [0–3], intermediate [4–5], and high [6–7] FAS level). It was expected that children with low familial affluence score lower on the KIDSCREEN-10 than their peers with high familial affluence. A small to medium effect size was expected for this mean difference [6–8].

Socio-demographics

Children and adolescents were asked about their age and gender. For the analyses, children aged 8–11 were compared with adolescents (12–18 years). We expected adolescents to report lower HRQoL than children and we expected girls to display lower HRQoL than boys. Small between-group effect sizes were expected. Respondents’ country membership was recorded. We expected cross-national variation in the average population health level assessed by the KIDSCREEN. A medium effect size was expected [6–8].

The KIDSCREEN-10, -27, -52, and the SDQ were applied in their child self-report version and their parent proxy report versions. The PedsQL, CHIP-AE, YQOL-S, HBSC-SCL, and the FAS were applied as child self-report measures. The CSHCN was applied in its parent proxy report version.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using the whole sample, and some analyses were repeated after stratifying by age (8–11 years and 12–18 years).

Reliability

The items of the KIDSCREEN-10 should be answered in a consistent manner as a basis for precise and reliable measurement. Internal consistency of item responses was assessed using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Values greater than 0.7 were considered as acceptable for group comparisons [28]. Reliability was also assessed by testing if repeated measurement (2 weeks later) lead to stable measurement results. Test–retest reliability was assessed with the intra class correlation coefficient (ICC). ICCs of 0.7 or higher were considered as acceptable.

Criterion validity

Criterion validity was assessed by determining the degree of Pearson correlation between the KIDSCREEN-10 and the original KIDSCREEN-52. Coefficients exceeding r = 0.7 were considered satisfactory [29]. As the KIDSCREEN-52 does not provide an overall score of HRQoL, a principal component analysis was conducted on the KIDSCREEN-52 dimension and a general factor was extracted. The general factor scores were treated as a substitute for a gold standard against that the KIDSCREEN-10 was correlated.

Convergent validity

It is important to study whether the KIDSCREEN scores are associated with measures assessing similar concepts or aspects that are related to the HRQoL construct to be measured. Such correlations indicate the “construct” validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 measurement. To analyze convergent validity, Pearson correlation coefficients between KIDSCREEN-10 scores and scores on other instruments were computed. Convergent validity was considered to be demonstrated when correlations with dimensions with a similar content to that of the KIDSCREEN-10 were moderate or high. Following the suggestions of [28] and [29], correlation coefficients between 0.1 and 0.3 were considered low, those from 0.31 to 0.5 moderate, and those exceeding 0.5 were considered large—while at the same time acknowledging that from the viewpoint of statistical prediction coefficients of r = 0.6 or 0.7 would be favorable. Validity coefficients were compared with the highest validity coefficient from any KIDSCREEN-27 scale.

Known groups validity

Construct validity was further evaluated by empirically testing previously developed hypotheses regarding differences between groups: Differences in HRQoL were a priori expected between healthy and physically or mentally ill children and adolescents, between respondents with high versus low familial socioeconomic status as well as between age and gender groups [31]. These hypotheses had been mentioned in the above chapter “measures”. Between-group differences were assessed using Cohen’s “d” as a measure of effect size (ES), by dividing the difference between the adjusted means by the overall standard deviation. Effect sizes of 0.2–0.5 were considered small; those between 0.51 and 0.8 moderate, and those over 0.8 were considered large [30]. A multiple analysis of covariance based on the general linear model was performed adjusted for age, gender, and country, which were included as covariates. Effect size measures were compared with the highest validity coefficients issued from any KIDSCREEN-27 scale.

Cases with missing data on any of the variables involved in a particular analysis were left out of that analysis. The tables contain detailed information about the number of subjects in each analysis.

Results

Sample characteristics

The final sample included 22,830 children and adolescents and the responses of 16,237 parents. The overall response rate was 68.9% and varied across countries, from 24.2 to 91.2% according to the sampling approach taken with higher response rates of children and parents in school samples. Data on the target child’s and the parents’ perceived health, together with data on parents’ marital and educational status, and place of residence were collected from parents who refused to participate. These data were compared with similar data from participants. Statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups on some variables. However, the magnitudes of the differences were small—e.g., 90.6% of the responders and 86.2% of the refuses rated their child’s health as good, very good, or excellent; 23.5% of the responders and 37.5% of the refuses had a low educational level. The results are reported in detail elsewhere [17]. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample, overall and by country. The child and adolescent samples were in general similar across all participating countries. The most notable differences between countries occurred in socioeconomic status (FAS) with, for example, 45.5% of the Czech Republic child sample reporting low FAS compared to only 7.5% of the French sample. Table 2 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the parent sample, overall and by country. Again notable differences between countries in socioeconomic status occurred. Besides the lack of parents data from IE and SE, and a generally lower response rate the distribution of age, gender, and SES was quite similar in both the parents and the children samples.

About 4.4% of the respondents had left one or more items of the KIDSCREEN-10 unanswered. The number of missing values in the KIDSCREEN-52 scales ranged from 2.6% (2.1%) to 4.0% (4.0%) for the self- (proxy) report version. The highest number of missing values was seen for the PedsQL scales (6.0–8.3%). The number of missing values for the other scales ranged from 1.0 (CHIP) to 6.9 (HBSC-SCL).

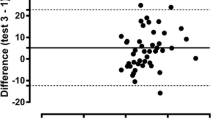

Internal consistency reliability and test–retest reliability and criterion validity

On average, respondents needed 3–5 min to fill in the KIDSCREEN-10. Table 3 shows results on the criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 for the overall sample. Correlations between the KIDSCREEN-10 self-report and parent report versions and scales of the KIDSCREEN-52 ranged from 0.24 to 0.72 and 0.27 to 0.72. Correlations between the KIDSCREEN-10 and the KIDSCREEN-52 Financial Resources and Being Bullied dimensions were below 0.7. The KIDSCREEN-10 self-report version correlated 0.91 with the ad hoc calculated general factor scores of the KIDSCREEN-52 self-report version. For the proxy report version, the same correlation of r = .91 was seen. Regarding reliability, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82 for the KIDSCREEN-10 self-report (8–11-year olds: 0.79; 12–18-year olds: 0.81) and 0.78 for the proxy report (8–11-year olds: 0.78; 12–18-year olds: 0.78). All Cronbach alpha results met the a priori defined criteria of alpha = 0.7. Test–retest ICC in the overall sample was 0.70 for the self-report (8–11-year olds: 0.64; 12–18-year olds: 0.69) and 0.67 for the parent report (8–11-year olds: 0.64; 12–18-year olds: 0.66). Only the ICC for the self-report in the overall sample met the a priori criteria of ICC = 0.7. The correlation between KIDSCREEN-10 self and parent proxy reports was r = 0.54 (8–11-year olds: 0.50; 12–18-year olds: 0.54). In comparison, correlations between corresponding KIDSCREEN-27 self- and proxy scores ranged from r = 0.45 to r = 0.61.

Construct validity

Convergent validity

Table 4 shows the results of analyzing convergent validity. The KIDSCREEN-10 self-report displayed moderate to high correlations in the expected direction with the self-report PedsQL scales and summary measure (0.57), the CHIP satisfaction scale (0.63), and the YQOL-S perceptual scale (0.61). Correlations between self-report scores on the KIDSCREEN-10 and parent scores on the CHQ were lower, ranging from 0.13 to 0.35, indicating small to moderate effects.

The KIDSCREEN-10 parent report showed low to moderate correlations with the self-reported PedsQL scales and summary measure (0.30), CHIP satisfaction scale (0.43) and YQOL-S perceptual scale (0.40). For the parent reported CHQ, correlations between 0.19 and 0.55 were observed. Moderate to large correlations (r = 0.52 and 0.36) were observed between the child self-report HBSC psychosomatic complaints checklist and the KIDSCREEN-10 self-report and parent report.

The KIDSCREEN-10 for some validation aspects achieved slightly lower validity coefficients compared to the largest coefficients issued from any of the original KIDSCREEN-27 scales.

Known groups validity

Table 5 shows the differences in KIDSCREEN-10 scores by physical and mental health status. Statistically significant differences between healthy and ill children on the CSHCN Screener instrument were found on the KIDSCREEN-10 score. The effect size was small (“d” = 0.32) for the self-report version and moderate (“d” = 0.52) for the parent report version.

Respondents categorized as healthy/normal on the SDQ had statistically significant higher scores on the KIDSCREEN-10 than those classified as probable cases. Effect sizes between these two groups on the KIDSCREEN-10 were large (“d” = 1.06 for children and “d” = 1.04 for parents) when informants (i.e., child or parent) on both instruments were the same. ES were smaller when different informants were used on the different measures (“d” between 0.67 and 0.76). Table 5 also shows mean T-values for the KIDSCREEN-10 score stratified by FAS. The higher the FAS category, the higher the scores on the KIDSCREEN-10. Effect sizes between those in high and low FAS categories were 0.42 for the self-report and 0.27 for the parent-report version of the KIDSCREEN-10.

The KIDSCREEN-10 on average achieved slightly lower effect size measures (validity coefficients) compared to the largest coefficients issued from any of the original KIDSCREEN-27 scales (Table 5).

Table 6 shows that children aged 8–11 scored higher than adolescents aged 12–18 on the KIDSCREEN-10 self-report and parent report version. This effect was especially large for the self-report version (“d” = 0.64 vs. 0.33). Sizeable differences in mean KIDSCREEN-10 scores were found between countries. Using the self-report version, the highest scores were observed in the Netherlands (53.9) and Austria (53.1) and the lowest values in France (46.8) and Poland (46.8). Using the parent report, Netherlands (53.8) and Spain (53.5) had the highest values and the United Kingdom (44.6) and Poland (45.8) had the lowest values.

Discussion

This study reports on the internal consistency, test–retest reliability, criterion, and construct validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score, a new short version of the KIDSCREEN-27/52 health-related quality of life questionnaire. The KIDSCREEN-52 and -27 HRQoL questionnaires were the first instruments for children and adolescents to be developed simultaneously in several countries and tested in a large representative, multinational sample of children and adolescents. This method ensures that different perspectives are taken into account during instrument development, avoid the imposition of possible cultural biases regarding instrument content, and permit valid cross-cultural comparisons. Moreover, it guarantees that the content will be important and relevant for the different cultures involved in the development of the measure [5, 7]. The KIDSCREEN-10 provides many of the advantages of the longer instruments but is easier to administer, to score, and to analyze. However, the assessment of HRQoL through one single value let to the loss of validity regarding some aspects. The loss of information relating to some physical and psychosocial aspects should be borne in mind when deciding which KIDSCREEN version to apply.

Correlations under 0.70 for most of the KIDCREEN-52 dimensions indicate that these are not quite as well represented by the new short KIDSCREEN score. On the other hand, correlation of 0.91 between the KIDSCREEN-10 and the ad hoc calculated general factor scores of the KIDSCREEN-52 showed that a common general HRQOL factor underlying the responses in the single KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions is well-represented.

In addition to the results presented here, previous analysis had shown that the instrument had good psychometric properties based on the Rasch model and analysis performed on differential item functioning [15]. Our psychometric analyses confirmed good internal consistency, permitting group comparison with even small sample sizes. Test–retest ICC coefficients were slightly lower than the a priori defined threshold of 0.7. This might be attributable to the 2-week test–retest interval that exceeds the 1-week timeframe of the KIDSCREEN items. Nevertheless, this shortcoming could e.g., reduce the sensitivity to change of the KIDSCREEN-10 in longitudinal studies with small samples. Further research is required to examine the stability of KIDSCREEN-10 scores over time as well as responsiveness to change.

In the present study, convergent and discriminant validity were indicated by the pattern of association between the KIDSCREEN-10 and scales from other generic HRQoL instruments. Correlations were generally highest with measures of mental health and psychological well-being and summary measures, indicating that both the KIDSCREEN-10 self and proxy report may be more focused on aspects of HRQoL related to mental health. The likelihood that the KIDSCREEN-10 is more focused on mental health is also borne out by the fact that the highest effect sizes were seen when the KIDSCREEN-10 was used to discriminate between respondents with poor and good mental health.

The factorial validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 was examined in another paper [15]: Results of confirmatory factor analysis (residual correlation ≤0.25) and Rasch IRT analysis (Infit msq = 0.72–1.10) indicated a good fit of the 1-factorial unidimensional measurement model of the KIDSCREEN-10. Seemingly that unidimensional latent trait is more defined by mental HRQoL aspects and not by physical ones. Nevertheless, the KIDSCREEN-10 also discriminated well between children when they were classified using measures related to physical health.

The correlations between KIDSCREEN-10 and KIDSCREEN-52 were similar and high in both the self and the parent report version (within analysis). However, correlation between the self and parent report version of the KIDSCREEN-10 and between corresponding scales of the KIDSCREEN-52 self and parent report version was of lower or similar magnitude at best [7]. Likewise, correlation between KIDSCREEN-10 parent report and the (self-reported) measures used for convergent validation was rather low. These results indicate a lack of convergence between both the self and the proxy versions. These finding are in line with previous results showing at best correlation of 0.6 between children and parent-rated HRQoL [5, 32, 33]. Previous studies found adolescents self-reports less positive about their health than parents reports [32]. A qualitative study on the KIDSCREEN items found evidence to suggest that the low agreement between child self-reports and parent proxy reports is rooted in different reasoning and different response styles rather than different interpretation of item content/statements [34]. Though parental proxy reports of their children’s HRQoL should be considered carefully as a potential substitute for self-reported ratings [35], it is widely recognized that self-reports and proxy reports both constitute important complementary information concerning children’s health [36]. This is especially important in younger children who might be less able to accurately report their own HRQoL [37].

Although adolescents are considered to be more accurate reporters of their HRQoL, the parent proxy KIDSCREEN-10 provides HRQoL data that is largely comparable to that of younger children [15]. This makes it possible to study the evolution of HRQOL across age groups and developmental stages in childhood and adolescence. Previous examinations on a longer KIDSCREEN-version showed the level of self and proxy agreement to depend on the country of origin [33]. It is beyond the scope of this paper but an issue for future research to examine which factors influence the child proxy agreement in the KIDSCREEN-10.

Although other studies have shown that HRQOL instruments are capable of discriminating between children and adolescents in different socioeconomic categories [38], the present study supports the idea that socioeconomic status might be more important for HRQoL in adolescents than in children. This finding contradicts the idea that in adolescence the increasing role of the peer group and the school environment reduces the effect of socioeconomic differences on HRQOL [39]. The observed differences between younger and older responders have also been reported in previous HRQoL studies [40], and the fact that the KIDSCREEN-10 confirms those differences supports its validity.

Limitations of the study included the fact that physical and mental health status were determined using self-report and parent report measures. This may be less reliable than using clinical records or clinical diagnoses to define children with physical and/or mental health conditions, and future studies should investigate the presence and size of differences in KIDSCREEN-10 scores when clinical diagnoses are used. Another study limitation was that sensitivity to change could not be tested due to the cross-sectional survey study design. This should be tested in future studies which might focus on testing the KIDSCREEN-10’s sensitivity to change within a randomized longitudinal intervention study with a control-group. Another limitation is that the KIDSCREEN-10 items were embedded in the longer KIDSCREEN-27 and -52 instruments. While this in particular could lead to overestimate the association between both measures [41], it is less likely that the KIDSCREEN-10 items are functioning in a different way if applied alone: A comparison of results issued from a stand alone application of the KIDSCREEN-10 revealed similar psychometric properties [16]. The KIDSCREEN-10 was developed in one half of the sample that was used to conduct the validation analyses. This in particular could lead to overestimation of the correlation between the KIDSCREEN-10 and the original KIDSCREEN-52, the reliability and the validity because the reduction of the instrument incorporates the peculiarities of that sample. However, a repetition of the psychometric analyses using only that half of the sample that was not used for construction resulted in similar coefficients.

Regarding the observed cross-national differences, further in-deep research will be carried out to examine which cross-national aspects such as socioeconomic status, differences in school and social systems could contribute to explain these differences. Our results showed the KIDSCREEN-10 to be capable for measuring cross-cultural differences between the countries under study.

Conclusions

In summary, the KIDSCREEN-10 score for children and adolescents provides a short self-reported HRQoL and well-being measure for children and adolescents, which was easy to administer, score, and interpret and which has demonstrated reliability and validity. Correlations under 0.70 for most of the KIDCREEN-52 dimensions indicate that these are not quite as well represented by the new short KIDSCREEN score as is a common general HRQOL factor underlying the responses in the single KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions. Results on validity showed the KIDSCREEN-10 to achieve similar validity as the KIDSCREEN-27 for some but not all aspects tested. Both the KIDSCREEN-10 self-report and proxy versions could be useful in large scale population interview surveys or in other situations where a brief instrument is useful such as routine monitoring in clinical and school settings. The self-report version was in fact included as an optional package in the large Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study 2005/2006 carried out in 41 European and North American countries and Israel [42]. More than a third of these countries applied the KIDSCREEN-10 [16]. The KIDSCREEN-10 proxy version was also included in the European Commission’s 2008 Flash EUROBAROMETER as an indicator for child and adolescent mental health issues [43]. It may thus contribute to European policies and public health by providing information on children and adolescents’ well-being and HRQoL both nationally and Europe-wide.

Abbreviations

- CHIP-AE:

-

Child Health and Illness Profile-Adolescent Edition

- CSHCN:

-

Children with Special Health Care Needs Screener

- DIF:

-

Differential item functioning

- FAS:

-

Family affluence scale

- HBSC:

-

Health behavior in school-aged children

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IRT:

-

Item response theory

- OLS:

-

Ordinal logistic regression

- PedsQoL:

-

Pediatric quality of life inventory

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- YQOL-S:

-

Youth quality of life instrument-surveillance version

References

WHOQOL Group. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41, 1403–1409.

Committee on Evaluation of Children’s Health NRC. (2004). Measuring children’s health. Children’s health, the nation’s wealth: Assessing and improving child health (pp. 91–115). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Seid, M., Varni, J. W., Segall, D., & Kurtin, P. S. (2004). Health-related quality of life as a predictor of pediatric healthcare costs: A two-year prospective cohort analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 48.

Varni, J. W., Burwinkle, T. M., & Lane, M. M. (2005). Health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric clinical practice: An appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 3, 34.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Wille, N., Wetzel, R., Nickel, J., & Bullinger, M. (2006). Generic Health-related Quality of life assessment in children and adolescents: Methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics, 24, 1199–1220.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Erhart, M., Bruil, J., Power, M., et al. (2008). The KIDSCREEN-52 Quality of Life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European Countries. Value in Health, 11, 645–658.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., & the European KIDSCREEN Group. (2006). The KIDSCREEN questionnaires—Quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents—Handbook. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publisher.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Auquier, P., Erhart, M., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Bruil, J., et al. (2007). The KIDSCREEN-27 Quality of Life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European Countries. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1347–1356.

Robitail, S., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Simeoni, M. C., Rajmil, L., Bruil, J., Power, M., et al. (2007). Testing the structural and cross-cultural validity of the KIDSCREEN-27 health-related quality of life questionnaire. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1335–1345.

Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcome Trust. (2002). Assessing health status and health-related quality of life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Quality of Life Research, 11, 193–205.

Hyland, M. (1992). A reformulation of quality of life for medical science. Quality of Life Research, 1, 267–272.

Testa, M. A., & Simonson, D. C. (1996). Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine, 334, 835–840.

Murray, C. J. L., & Lopez, A. D. (1997). The utility of DALYs for Public health policy and research: A reply. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 75, 377–381.

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., Bayliss, M. S., McHorney, C. A., Rogers, W. H., & Raczek, A. (1995). Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: Summary of results from the medical outcome study. Medical Care, 33(4S), AS264–AS279.

Erhart, M., Rajmil, L., Hagquist, C., Herdman, M., Simeoni, M.-C., Auquier, P., et al. (submitted). Development of the KIDSCREEN-10 child and adolescent’s quality of life short single score measure. In revision: Assessment

Erhart, M., Ottova, V., Gaspar, T., Nickel, N., Ravens-Sieberer, U., & the HBSC Positive Health Focus Group. (2009). Measuring mental health and well-being of school-children in 15 European countries: Results from the KIDSCREEN-10 Index. International Journal of Public Health, 54, 160–166.

Berra, S., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Tebe, C., Bisegger, C., Duer, W., et al. (2007). Survey methods and representativeness of European national surveys of the KIDSCREEN study. BMC Public Health, 7, 182.

Varni, J. W., Seid, M., & Kurtin, P. S. (2001). PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care, 39, 800–812.

Starfield, B., Riley, A., Green, B., Ensminger, M., Ryan, S., & Kelleher, H. (1995). The adolescent CHIP: A population-based measure of health. Medical Care, 33, 553–566.

Edwards, T. C., Huebner, C. E., Connell, F. A., & Partick, D. L. (2002). Adolescent quality of life, part I: Conceptual and measurement model. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 275–286.

Patrick, D. L., Edwards, T. C., & Topolski, T. D. (2002). Adolescent quality of life, part II: Initial validation of a new instrument. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 287–300.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Torsheim, T., Hetland, J., Freeman, J., Danielson, M., et al. (2008). An international scoring system for self-reported health complaints in adolescents. European Journal of Public Health, 18(3), 294–299.

Bethell, C. D., Read, D., Stein, R. E., Blumberg, S. J., Wells, N., & Newacheck, P. W. (2002). Identifying children with special health care needs: Development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 2, 38–48.

Bethell, C. D., Read, D., Neff, J., Blumberg, S. J., Stein, R. E., Sharp, V., et al. (2002). Comparison of the children with special health care needs screener to the questionnaire for identifying children with chronic conditions-revised. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 2, 49–57.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

Anonymous. SDQ: Scoring of the SDQ. http://sdqinfo.com/b4html. Accessed 30 Sept 2008.

Currie, C., Molcho, M., Boyce, W., Holstein, B., Torsheim, T., & Richter, M. (2008). Researching health inequalities in adolescents: The development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 1429e–1436e.

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. J. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: Mc-Graw-Hill.

Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A. W. M., Dirk, L., Knol, D. L., et al. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, e34–e42.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eiser, C., & Morse, R. (2001). A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Archives of Disease in Children, 84, 205–211.

Theunissen, N. C., Vogels, T. G., Koopman, H. M., Verrips, G. H., Zwinderman, K. A., Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P., et al. (1998). The proxy problem: Child report versus parent report in health-related quality of life research. Quality of Life Research, 7, 387–397.

Robitail, S., Simeoni, M. C., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Bruil, J., & Auquier, P. (2007). Children proxies’ quality-of-life agreement depended on the country using the European KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 469.e1–469.e13.

Waters, E., Stewart-Brown, S., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2003). Agreement between adolescent self-report and parent reports of health and well-being: Results of an epidemiological study. Child: Care Health Development, 29, 501–509.

Davis, E., Nicolas, C., Waters, E., Cook, K., Gibbs, L., Gosch, A., et al. (2007). Parent-proxy and child self-reported health-related quality of life: Using qualitative methods to explain the discordance. Quality of Life Research, 16, 863–871.

Jokovic, A., Locker, D., & Guyatt, G. (2004). How well do parents know their children? Implications for proxy reporting of child health related quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 13, 1297–1307.

Eiser, C., & Morse, R. (2001). Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 10, 347–357.

Starfield, B., Riley, A. W., Witt, W. P., & Robertson, J. (2002). Social class gradients in health during adolescence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 354–361.

West, P. (1997). Health inequalities in early years: Is there equalisation in youth? Social Science and Medicine, 44, 833–858.

Vingilis, E. R., Wade, T. J., & Seeley, J. S. (2002). Predictors of adolescent self-rated health. Analysis of the National Population Health Survey. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 93, 193–197.

Coste, J., Guillemin, F., Pouchot, J., & Fermanian, J. (1997). Methodological approaches to shortening composite measurement scales. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50, 247–252.

Currie, C. E., Gabhainn, S. N., & Godeau, E. (2008). Inequalities in young peoples health. HBSC international report from the 2005/2006 Survey (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No. 5). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Gallup Organization. (2009). Parent’s views on the mental health of their child. Analytical report. Flash Eurobarometer report 246. Brussels: European Commision, DG Communication, Public Opinion 2009.

Acknowledgments

The KIDSCREEN project was financed by a grant from the European Commission (QLG-CT-2000-00751) within the EC 5th Framework-Program “Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources”.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Members of the KIDSCREEN group are as follows: Austria: Wolfgang Duer, Kristina Fuerth; Czech Republic: Ladislav Czerny; France: Pascal Auquier, Marie-Claude Simeoni, Stephane Robitail, Germany: Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer (international coordinator in chief), Michael Erhart, Jennifer Nickel, Veronika Ottova, Bärbel-Maria Kurth, Angela Gosch, Ursula von Rüden; Greece: Yannis Tountas, Christina Dimitrakakis; Hungary: Agnes Czimbalmos, Anna Aszman; Ireland: Jean Kilroe, Celia Keenaghan; The Netherlands: Jeanet Bruil, Symone Detmar, Eric Veripps; Poland: Joanna Mazur, Ewa Mierzejeswka; Spain: Luis Rajmil, Silvina Berra, Cristian Tebé, Michael Herdman, Jordi Alonso; Sweden: Curt Hagquist; Switzerland: Thomas Abel, Corinna Bisegger, Bernhard Cloetta, Claudia Farley; United Kingdom: Mick Power, Clare Atherton, Katy Phillips.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Rajmil, L. et al. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 19, 1487–1500 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5