Abstract

Background

The use of global health items permits an efficient way of gathering general perceptions of health. These items provide useful summary information about health and are predictive of health care utilization and subsequent mortality.

Methods

Analyses of 10 self-reported global health items obtained from an internet survey as part of the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) project. We derived summary scores from the global health items. We estimated the associations of the summary scores with the EQ-5D index score and the PROMIS physical function, pain, fatigue, emotional distress, and social health domain scores.

Results

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses supported a two-factor model. Global physical health (GPH; 4 items on overall physical health, physical function, pain, and fatigue) and global mental health (GMH; 4 items on quality of life, mental health, satisfaction with social activities, and emotional problems) scales were created. The scales had internal consistency reliability coefficients of 0.81 and 0.86, respectively. GPH correlated more strongly with the EQ-5D than did GMH (r = 0.76 vs. 0.59). GPH correlated most strongly with pain impact (r = −0.75) whereas GMH correlated most strongly with depressive symptoms (r = −0.71).

Conclusions

Two dimensions representing physical and mental health underlie the global health items in PROMIS. These global health scales can be used to efficiently summarize physical and mental health in patient-reported outcome studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL)—that is, functioning and well-being in physical, mental, and social domains of life–has been shown to be useful in screening for disability and in improving communication between patients and clinicians [1, 2]. Generic HRQOL profile measures use multiple items to assess each of multiple domains of health. To reduce response burden, short-form HRQOL measures such as the SF-36 health survey are widely used [3]. Although their brevity makes short-form measures practical for widespread use, even the SF-36 requires 7–10 min to complete.

The Dartmouth COOP Charts were designed to provide the briefest possible measure of HRQOL [4]. This instrument consists of global items (“chart”) to represent each domain of health. These items are administered using five response choices [4]. For example, one of the charts assesses overall health using the single item, “How would you rate your health in general? (Excellent, Very good, Good, Fair, Poor.)” The Charts have the advantage of ease of administration and scoring but tend to be less precise and specific than multi-item scales. The Charts are one of the original examples of the use of global health items to assess multiple HRQOL domains.

Global health items are evaluations of health in general rather than specific elements of health. Global items allows respondents to weigh together different aspects of health to arrive at a ‘bottom-line” indicator of their health status. They allow an efficient assessment of self-reported health. Global health items are predictive of important future events such as health care utilization and mortality [5].

The aim of this study was to evaluate global items representing physical health, pain, fatigue, mental health, social health, and overall health. These domains reflect the health framework used by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; see www.nihpromis.org) [6]. We examine the individual items and assess possible aggregation of them into underlying dimensions of health as measured in PROMIS. We first evaluate whether scoring the items together as a single summary scale is supported empirically. Then we examine alternatives that better reflect the data.

Methods

Study design

The PROMIS item banks were administered via web-based survey to a national internet panel maintained by Polimetrix (now YouGovPolimetrix; see www.polimetrix.com). The field test involved administering the item banks from five domains (i.e., physical functioning, pain, fatigue, emotional distress, social health) to selected participants. We randomly assigned some respondents to complete full item banks, that is, all the items within a defined domain-specific bank such as physical function or fatigue. We randomly assigned other respondents to sets of 7 consecutive items for each of 14 hypothesized sub-domains from the 5 health domains.

Measures

The 10 global health items include ratings of the five core PROMIS domains and ratings that cut across domains (Appendix). The PROMIS global health item set includes the most widely used self-rated health item (global01). Previous research has shown that this item taps both physical health and mental health but reflects physical health more than mental health, especially for those with low income [5]. PROMIS includes a single item that provides a pure rating of physical health (global03) and another item for mental health (global04). Also included is an overall quality of life item (global02) that is a very strong indicator of mental health (see e.g., Lorenz et al. [7]). The remaining items provide global ratings of physical function (global06), fatigue (global08), pain (global07), emotional distress (global10), and social health (global05 and global09).

We administered all of the items except the rating of pain on average (global07) using five-category response scales (see Appendix). We recoded global07 from the 0–10 scale to 5 categories based on grouping of 0–10 response scales for the Sheehan Disability Scale and the Flushing Symptom Questionnaire [8] as follows: 0 = 1; 1–3 = 2; 4–6 = 3; 7–9 = 4; 10 = 5.

We also administered the EQ-5D survey, a widely used generic HRQOL preference-based measure, to study participants. We examine the empirical associations of the PROMIS global items with the EQ-5D. For this purpose, we derived the EQ-5D preference-based index score using the US general population weights [9]. The EQ-5D is anchored by 0 (dead) and 1 (perfect health). The lowest possible score for the EQ-5D is −0.11, indicating a health state rated worse than being dead by the sample of 4,048 people in the US valuation sample.

Study participants

The PROMIS sample was selected to be comparable to distributions of gender, age groups, race/ethnicity (white/African–American/Hispanic/other) and education (high school or less versus more than high school) based on the 2000 US census data [10]. We identified study participants from the Polimetrix internet panel.

Because of the number of item banks being tested, we employed a complex data collection strategy. This strategy included two arms and a total sample size of 21,133 (see Fig. 1). Polimetrix recruited a total of 19,601 subjects; we recruited the remaining 1,532 subjects from the PROMIS research sites. In the full bank testing arm, we administered 2 item banks (56 item per bank) to 7,005 persons. In the second arm, we administered randomly selected 7-item blocks from each of the 14 hypothesized PROMIS sub-domains to 14,128 individuals. The PROMIS research sites and the Polimetrix sample included both community and clinical samples. The clinical samples included persons with heart disease (n = 1,156), cancer (n = 1,754), rheumatoid arthritis (n = 557), osteoarthritis (n = 918), psychiatric disorders (n = 1,193), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 1,214), spinal cord injury (n = 531), and other conditions (n = 560).

Table 1 provides a summary of sample characteristics. The average age was 53 and 52% were female. The majority were non-Hispanic white (80%); 9% were Latino and 9% non-Hispanic black. The sample was well educated—only 19% had only a high school degree or less.

Analysis plan

We estimated polyserial correlations of the global items with the EQ-5D. In addition, we examined item-scale correlations and conducted confirmatory categorical factor analysis (based on polychoric correlations) to evaluate whether the 10 global health items could be combined into a single unidimensional scale. Next, we performed exploratory factor analysis on the matrix of polychoric correlations to identify the number of underlying dimensions. We evaluated the resulting two factors by estimating item-scale correlations and internal consistency reliability. We used Mplus 5.1 software [11] to estimate confirmatory categorical factor analysis models, specifying weighted least squares mean and variance estimation. Because of our large sample size we do not rely on the chi-square statistic to evaluate the acceptability of the models. We estimated practical fit of the models using the confirmatory fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). We averaged items to form physical and mental health composites and estimated associations of these composites with the EQ-5D and the nine PROMIS domain scores (physical functioning, pain behavior, pain impact, fatigue, anxiety, anger, depressive symptoms, satisfaction with discretionary social activities, satisfaction with social roles). Finally, we estimated item threshold and discrimination parameters for the final physical and mental health scales using the graded response model [12, 13]. Based on the item parameters we calculated item information, the contribution of each item to overall test precision [12]. As an estimate of the contribution of each item to overall test precision, we weighted item-level information values, which are computed as the expected item information across the score distribution of our sample.

Results

Item-scale correlations for the 10 global health items ranged from 0.53 (global7: rating of pain) to 0.80 (global09: satisfaction with social roles) and internal consistency reliability was 0.92. However, the single-factor confirmatory categorical factor analysis model for all 10 items was statistically rejectable (χ 2 = 19,619.82, df = 15, P ≤ 0.001) and did not fit the data very well (CFI = 0.927; TLI = 0.961; RMSEA = 0.249).

The eigenvalues from a principal components analysis of the 10 global items were 6.25, 1.20, 0.75, 0.44, 0.39, 0.30, 0.22, 0.20, 0.18, and 0.05. The scree plot and parallel analysis number of factor criteria suggested two underlying dimensions for the 10 items. We performed an exploratory factor analysis and found support for a physical health and mental health factor (see Table 2). Satisfaction with discretionary social activities (global05) loaded on mental health whereas satisfaction with social roles (global09) loaded on both physical and mental health (as did global02: quality of life; and global08: fatigue). The estimated correlation between the physical and mental health factors was 0.63. These results were also supported by our confirmatory categorical factor analysis, but three residual correlations were added to obtain acceptable model fit; see Table 2 (global01 with global03 r = 0.14, global04 with global10 r = 0.14, and global08 with global10 r = 0.15; χ 2 = 5,295.66, df = 17, P < 0.0001; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.12). The estimated correlation between the physical and mental health factors was 0.69.

Based on the exploratory factor analysis, we evaluated a physical health scale with the 5 items loading highest on the physical health factor. Global09 (satisfaction with social roles) was excluded because it correlated about equally with physical and mental health. Item-scale correlations for the five physical health items ranged from 0.57 (global07: rating of pain) to 0.79 (global01: rating of general health; and global03: rating of physical health). All 5 items correlated higher with the physical health scale than with the mental health scale. We fit a single-factor categorical confirmatory factor analytic model for the five physical health items and found that it was statistically rejectable (χ 2 = 3,060.81, P < 0.001) and showed less than adequate practical fit according to the RMSEA index (CFI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.220). By adding a residual correlation (r = 0.29) between global01 (rating of general health) and global03 (rating of physical health) to the initial model, we found that the fit of the model improved significantly (χ 2 = 2,248.57, df = 1, P < 0.001) and the practical fit indices also improved (χ 2 = 419.56, P < 0.001; CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.081).

We also evaluated a mental health scale with 4 items. Three of these items correlated most highly with the mental health scale. The fourth item, global02 (quality of life), correlated about equally with physical and mental health, but was also included because of prior evidence that it is primarily an indicator of mental health. Item-scale correlations for the 4 hypothesized mental health items ranged from 0.64 (global10: emotional problems) to 0.78 (global04: rating of mental health). One item (global09, satisfaction with social roles) had higher correlation with the global physical health scale than with the mental health scale; the 4 mental health items correlated strongest with the mental health scale. The single-factor categorical confirmatory factor analytic model we fit for these 4 mental health items was statistically rejectable (χ 2 = 1,616.80, df = 2, P ≤ 0.001), and had mixed results in terms of practical fit (CFI = 0.983; TLI = 0.975; RMSEA = 0.196). When we added a residual correlation (r = 0.16) between global04 (rating of mental health) and global10 (bothered by emotional problems) to the initial model, the fit improved significantly (χ 2 = 1,114.27, df = 1, P < 0.001) and the practical fit of the model improved (χ 2 = 151.222, P ≤ 0.001; CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.995; RMSEA = 0.084).

Based on these results, we formed two-four-item scales by averaging together the items scored on a 1–5 possible range. Our physical health items included global03 (physical health), global06 (physical function), global07 (pain) and global08 (fatigue). Our mental health items included global02 (quality of life), global04 (mental health), global05 (satisfaction with discretionary social activities), and global10 (emotional problems). The global physical health (GPH) scale excluded global01 (general health) because of its substantial residual correlation with global03 (physical health). We retained global03 in the scale rather than global01 to emphasize the physical nature of the construct. The GPH had an internal consistency reliability of 0.81 (mean = 3.79, SD = 0.76). We excluded global09 (satisfaction with social roles) from the global mental health (GMH) scale because of its higher correlation with the GPH scale. The GMH had an internal consistency reliability of 0.86 (mean = 3.60, SD = 0.89). The two scales were substantially inter-correlated (r = 0.63). In addition, we found that GPH correlated more strongly with the EQ-5D than did the GMH (r = 0.76 vs. 0.59). The R-square in a regression of the EQ-5D on the GPH and GMH was 0.60, indicating that the PROMIS global health composites share 60% of variance in common with the EQ-5D.

Correlations of the global health items and GPH and GMH with the nine PROMIS domain scores and the EQ-5D are given in Table 3. The largest correlations for global01 (rating of general health), global02 (quality of life), global03 (rating of physical health), global08 (rating of fatigue), and global09 (satisfaction with social roles) were with the fatigue domain. Global04 (rating of mental health), global05 (satisfaction with discretionary social activities) and global10 (emotional problems) correlated most strongly with the depressive symptoms domain. Global06 (carry out everyday physical activities) correlated most strongly with physical functioning whereas global07 (rating of pain) correlated highest with pain impact. The GPH correlated most strongly with pain impact (r = −0.75), fatigue (r = −0.73), and physical functioning (r = 0.71). GMH correlated most strongly with depressive symptoms (r = −0.71), fatigue (r = −0.68), and anxiety (r = −0.65).

Correlations of the global items with the EQ-5D ranged from 0.51 to 0.77. The largest correlations with the EQ-5D were for the global ratings of pain, physical functioning, and satisfaction with social roles. Our regression of the EQ-5D on the global items revealed that all items except two (global03: rating of physical health; global05: satisfaction with discretionary social activities) had significantly unique associations (R-square = 0.64).

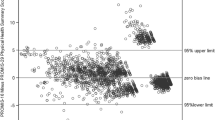

We estimated item parameters from the graded response model for the 4 global physical health items (Table 4) and 4 global mental health items (Table 5). The range of item threshold values indicates satisfactory coverage of the underlying latent trait from ~−4.0 to 2.0 for Physical Health and between −3.0 and 1.5 for Mental Health. Global06 (carry out everyday physical activities) had the highest slope (a parameter in Table 4) and the largest information for the physical health items whereas global04 (rating of mental health) had the largest information for the mental health items. We found the lowest item information for items phrased to elicit ratings of undesirable domains of health (pain, fatigue, emotional problems).

Discussion

The results of our study provide some support for the construct validity of the global health items based on their correlations with comparable multi-item scales from PROMIS. For example, the global rating of mental health (global04) correlated most strongly with the PROMIS depressive symptoms scale; the global rating of fatigue (global08) correlated strongest with the PROMIS fatigue scale.

In addition, our exploratory factor analyses suggested two underlying dimensions for the global health items. One dimension is defined by indicators of primarily physical health and the other by indicators of mental health. Similar underlying factors have been found in previous research [14–16]. Moreover, the correlation we estimated between the GPH and GMH (r = 0.63) in this study was very similar to correlations between physical and mental health factors derived from the SF-36 (e.g., r = 0.62 in Farivar et al. [17]) and other measures of HRQOL [18] using oblique rotation. We recommend scoring the scales using 8 items, but also scoring the remaining 2 items as single items separately: Global01 (General health) and Global09 (satisfaction with social roles).

A major advantage of the global health scales developed here is the brevity of the resulting measure for gathering summary information about health. For the two scales, each of which had 4 items, we obtained reliabilities of 0.81 and 0.86; together they require about 2 min to complete. In contrast, the SF-36 takes about 7–10 min to administer and the estimated reliabilities are about 0.88–0.93 for the SF-36 physical and mental health composites [19]. The SF-12™ [20] and SF-8™ [21] Health Surveys have completion times and reliabilities that are comparable to the current survey. Future head-to-head comparisons of the present instruments and these instruments would be beneficial.

Although the physical and mental health scales are valuable for summarizing health, if a study shows improvement in one of the summary measures and decrement in the other, drawing an overall conclusion can be difficult. Moreover, attrition of study participants over time because they have died presents challenges for longitudinal comparisons based on these global scores because of the bias of dropping those who die from the analysis. Preference-based measures are designed to derive a single summary score that links morbidity and mortality by anchoring the metric so that 0 is “as bad as being dead” and 1 represents “perfect health.” This study showed noteworthy associations of the global health scores with the EQ-5D preference-based score; 60% of the variance was shared in common. A separate paper derives equations estimating EQ-5D index scores from these composite scores [22].

Investigators can use the 10 global health items in future studies to assess global physical and mental health. The items are available as part of the PROMIS item banks at: http://www.nih.promis.org. In addition, the items can be examined separately to provide specific information about perceptions of physical function, pain, fatigue, emotional distress, social health and general perceptions of health. Future studies are needed to evaluate the relative validity of the global scales compared with physical and mental health composites derived from other measures such as the SF-12 and SF-36.

References

McHorney, C. A. (1999). Health status assessment methods for adults: Past accomplishments and future challenges. Annual Review of Public Health, 20, 309–335.

Velikova, G., Booth, L., Smith, A. B., Brown, P. M., Lynch, P., Brown, J. M., et al. (2004). Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 714–724.

Coons, S. J., Rao, S., Keininger, D. L., & Hays, R. D. (2000). A comparative review of generic quality of life instruments. PharmacoEconomics, 17, 13–35.

Nelson, E. C., Wasson, J. H., Johnson, D. J., & Hays, R. D. (1996). Dartmouth COOP functional health assessment charts: Brief measures for clinical practice. In B. Spilker (Ed.), Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials (2nd ed., pp. 161–168). New York: Lippincott-Raven Publishers.

Bjorner, J. B., Fayers, P. M., & Idler, E. L. (2005). Self-rated health. In P. M. Fayers & R. D. Hays (Eds.), Assessing quality of life (pp. 309–323). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cella, D., Yount, S., Rothrock, N., Gershon, R., Cook, K., Reeve, B., et al. (2007). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care, 45(5), S3–S11.

Lorenz, K. A., Cunningham, W. E., Spritzer, K. L., & Hays, R. D. (2006). Changes in symptoms and health-related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of adults in treatment for HIV. Quality of Life Research, 15, 951–958.

Norquist, J. M., Watson, D. J., Yu, Q., Paolini, J. F., McQuarrie, K., & Santanello, N. C. (2007). Validation of a questionnaire to assess niacin-induced cutaneous flushing. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 23, 1549–1560.

Shaw, J. W., Johnson, J. A., & Coons, S. J. (2005). U.S. valuation of the EQ-5D health states: Development and testing of the D1 model. Medical Care, 43, 203–220.

Liu, H., Cella, D., Gerhson, R., Shen, J., Morales, L. S., Riley, W., & Hays, R. D. (submitted). Representativeness of the PROMIS internet panel.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus user’s guide (version 5.1). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Samejima, F. (1994). Estimation of reliability coefficients using the test information function and its modifications. Applied Psychological Measurement, 18, 229–244.

Thissen, D., Chen, W.-H., & Bock, R. D. (2003). Multilog (version 7.0). Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International.

Cella, D., Chang, C.-H., Wright, B., Von Roenn, J., & Skeel, R. (2005). Defining higher order dimensions of self-reported health: Further evidence for a two-dimensional structure. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 28(2), 122–141.

Chang, C.-H., Wright, B., Cella, D., & Hays, R. (2007). The SF-36 physical and mental health factors were confirmed in cancer and HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 68–72.

Hays, R. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1990). The structure of self-reported health in chronic disease patients. Psychological Assessment, 2, 22–30.

Farivar, S. S., Cunningham, W. E., & Hays, R. D. (2007). Correlated physical and mental health summary scores for the SF-36 and SF-12 health survey, V. 1. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 54.

Revicki, D. A., Sorensen, S., & Wu, A. W. (1998). Reliability and validity of physical and mental health summary scores from the Medical Outcomes Study HIV health survey. Medical Care, 36, 126–137.

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1994). SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute.

Ware, J. E., Jr., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-item short-form health survey. Medical Care, 34, 220–233.

Ware, J. E., Jr., Kosinski, M., Dewey, J. E., & Gandek, B. (2001). How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: A manual for users of the SF-8 health survey (with a supplement on the SF-6 health survey). Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated.

Revicki, D., Kawata, A. K., Harnam, N., Chen, W-H., Hays, R. D., & Cella, D. (2009). Predicting EuroQol (EQ-5D) scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items and domain item banks in a United States sample. Quality of Life Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9489-8.

Acknowledgments

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a US. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Roadmap initiative to develop a computerized system measuring patient-reported outcomes in respondents with a wide range of chronic diseases and demographic characteristics. PROMIS was funded by cooperative agreements to a Statistical Coordinating Center (Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, PI: David Cella, PhD, U01AR52177) and six Primary Research Sites (Duke University, PI: Kevin Weinfurt, PhD, U01AR52186; University of North Carolina, PI: Darren DeWalt, MD, MPH, U01AR52181; University of Pittsburgh, PI: Paul A. Pilkonis, PhD, U01AR52155; Stanford University, PI: James Fries, MD, U01AR52158; Stony Brook University, PI: Arthur Stone, PhD, U01AR52170; and University of Washington, PI: Dagmar Amtmann, PhD, U01AR52171). NIH Science Officers on this project are Deborah Ader, Ph.D., Susan Czajkowski, PhD, Lawrence Fine, MD, DrPH, Louis Quatrano, PhD, Bryce Reeve, PhD, William Riley, PhD, and Susana Serrate-Sztein, PhD. Ron D. Hays was also supported by the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement in Minority Elderly (P30AG021684), and the UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT, National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health & Health Disparities (P20MD000148 and P20MD000182). This manuscript was reviewed by the PROMIS Publications Subcommittee prior to external peer review. See the web site at www.nihpromis.org for additional information on the PROMIS cooperative group.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hays, R.D., Bjorner, J.B., Revicki, D.A. et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 18, 873–880 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9