Abstract

In this study, we develop the first daily news-based Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) index for Nigeria, which was previously not covered in recent EPU indices. The need to track economic uncertainties in Nigeria becomes crucial for investment and policy, especially with the renewed interest in the country as an important investment destination. To construct the EPU index, we use relevant keywords from articles in prominent newspapers in the country, covering the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the COVID pandemic, with a data scope of January 2010 to November 2022. We evaluate the predictability of the index by examining its connection with economic and financial variables like exchange rates, stock prices, and inflation in Nigeria. The results are robust to alternative model specifications, data frequencies, and multiple forecast horizons. We hope to extend this exercise to other useful indices, including Geopolitical Risk, Financial Stress Indicators, and Monetary Policy Uncertainty, which are not readily available for Africa, including Nigeria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The literature on the development of news-based economic policy uncertainty (EPU) indices is gradually emerging, and currently, the existing indices are limited to developed and emerging economies (see Baker et al. (2016), Davis (2016), and Ahir et al. (2022)Footnote 1,Footnote 2. In other words, it is hard to find a version of any of these EPU indices being replicated for any African country despite increasing representation in the global economic integration and strong growth experience over the years (OECD 2018). In bridging this gap, we construct the index for Nigeria as the continent’s largest and most developed economy. As the largest producer of oil in the continent, some specific uncertainty-triggered events, such as oil price shocks, usually culminate into panic buying and selling and often lead to a rise in the level of uncertainty in the country. Similarly, discussion around fuel subsidy removal and its implication for fiscal sustainability also has a way of infusing uncertainty into the economic atmosphere of the country. This peculiarity to the Nigerian economy is the sudden rise in the prices of goods and services that usually follow each time this debate ensues. Other sources of uncertainty such as unexpected and sudden central bank intervention, policy inconsistencies after elections or when power shifts from one party to another, fall in global oil prices, oil price shocks, and uncertain government response, unethical public policy and practices (see Ozili 2022), among other sources that are peculiar to Nigeria, have strengthened our interest in this economy.

In addition to addressing Nigeria’s underrepresentation in the construct of country-level economic policy uncertainty index (see Ozili 2022), this study is an attempt to circumvent wrong policy recommendations that could arise from analyzing Nigerian fundamentals using the global index as well as conditional volatility of some macro variables (see Aye and Kotur 2022; Kumeka et al. 2023), which might not accurately reflect the domestic dynamics in the country. To our knowledge, ours is the first attempt to construct a country-specific uncertainty index for an African country, especially Nigeria, and use the same to predict the behaviour of market fundamentals such as exchange rate and stock return volatility, as well as inflation and inflation variance in the country.

This study presents a daily index for economic policy uncertainty within the context of Nigeria. Our index covers most of the prominent newspapers in Nigeria, such as the Punch, This Day, The Guardian, Business Day, Daily Trust, Tribune, PM news, and Leadership newspapers.Footnote 3 We utilize several keywords similar to those of Baker et al. (2016), Davis (2016), and Ahir et al. (2022) to make the outcome comparable to the existing EPUs (see Al-Thaqeb and Algharabali 2019 for a detailed review). For each of these newspapers, we retrieve daily news articles containing terms such as uncertainty, uncertain, uncertainties, economic, economy, senate, deficit, the central bank of Nigeria, legislation regulation, house of representatives, house of reps, national assembly, and CBN, published between 2010 and 2023. It is important to highlight the approach followed to produce the index is not trivial. Unlike Baker et al. (2016), Davis (2016) and Ahir et al. (2022), it is more tedious to extract the news articles for Nigeria as virtually all of them do not have APIs that provide seamless access to their news content. This may be why Nigeria has not been included in the computation of global uncertainties. Thus, we had to adopt alternative tools to extract the keywords. These alternative tools include Web Scraping, Sitemaps Access, and RSS Feeds.Footnote 4 One important selling point of our index is that it is of daily frequency, and therefore, information about public sentiments on any policy decision in the country will come in handy for relevant authorities to review and process further actions. In addition, with our daily data scope covering the period of 1/1/2010–3/9/2023Footnote 5, we offer Nigeria’s first comprehensive daily dataset on the EPU index. It is, however, important to highlight that our study relates to those of Baker et al. (2016), Davis (2016), and Ahir et al. (2022), except that we focus on the continent that is hardly represented in the construction of country-specific indices including EPU index. Thus, we contribute to the growing literature using articles published in the prominent newspapers of Nigeria to construct the uncertainty index. Similar efforts include the geopolitical risk constructed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2019), climate policy uncertainty by Faccini et al. (2021), global fear index due to COVID-19 by Salisu and Akanni (2020), uncertainty due to COVID-19 pandemic by Narayan et al. (2021), among others. We hope to extend the literature on Africa to the mentioned indices, which currently lie outside the focus of this study.

We test the applicability of our EPU index by conducting some empirical exercises with a number of financial series, such as stock price and exchange rate, to assess how these series connect with the index as established in the literature (see, for example, Xu 2020). Our choice of variables for the empirical application is motivated by their high exposure to systematic and unsystematic risks (see De Santis 2018). We show results that lend credence to the predictive contents of the constructed EPU index for Nigeria. More importantly, we demonstrate that including the index in the predictive models for financial series, such as exchange rate and stock prices, improves their forecasts.

Following this introduction, the rest of the paper is structured thus. Section 2 presents the steps involved in constructing the EPU index. While the penultimate section demonstrates and presents the results from the empirical application using the EPU index, the final section, Sect. 4, anchors the study’s conclusion.

2 Methodological procedure for the EPU index

2.1 Data collection

Developing a text-based index usually begins with identifying relevant keywords related to the subject matter: economic policy uncertainty. Note that several EPU indices are already published (see https://www.policyuncertainty.com/), albeit focusing on developed and emerging economies without any representation from Africa. One common feature of these indices is that they adopt similar keywords whose choice is pioneered by Baker et al. (2016) to facilitate cross-country comparison of datasets. In light of this, we adopt similar keywords such as uncertainty, uncertain, uncertainties, economic, economy, senate, deficit, the central bank of Nigeria, legislation, regulation, house of representatives, house of reps, national assembly, and CBN. Meanwhile, some keywords that reflect the peculiarities of Nigeria, such as the Central Bank of Nigeria, House of Representatives, National Assembly, and CBN, are included to produce a more realistic index for Nigeria.

The second step involves downloading all available news articles and extracting relevant news articles containing these keywords from eight notable newspapers in Nigeria. As previously noted, the newspapers are Punch, ThisDay, The Guardian, Business Day, Daily Trust, Nigerian Tribune, PM news, and Leadership. Table 1 shows the number of newspapers downloaded and those containing at least a keyword. At the end of the procedure, we obtain daily word counts for each keyword over the period of 1/1/2010–11/30/2022.Footnote 6

2.2 Index construction

To construct the index, we sum the daily word counts for all the keywords, defined in this paper as EPU (i.e., Economic Policy Uncertainty), and thereafter, we run a heteroskedasticity-consistent ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of EPU on day-of-the-week dummy variables to accommodate the possible distinct variations in public sentiments in the five days of the week.Footnote 7 To avoid a dummy trap, we exclude the Friday dummy while the resulting constant and residuals from the OLS model are added to adjust the data for day-of-the-week effects:

where EPU is the daily sum of word count for each of the keywords; \({D_{i,t}}\) is for the week-day dummy variables for four days (for a 5-day week) since one dummy has to be excluded to avoid dummy trap; \(\alpha\)is the regression constant while \({\varepsilon _t}\) is the disturbance term. In the appendix (Table A1), we present the regression estimates for the dummy variables of the day-of-the-week effects, which are significant. The (day-of-the-week) adjusted EPU (\(EPU_{t}^{{adj}}\)) is obtained as \(EPU_{t}^{{adj}}=\hat {\alpha }+{\hat {\varepsilon }_t}\). In the final step, we compute the index as:

3 Some empirical analyses

3.1 Some preliminary analyses

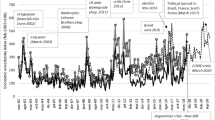

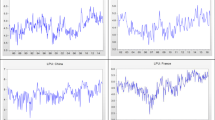

We have prepared a dedicated website to host and disseminate the datasets for the \(EPU_{t}^{{adj}}\)index (see https://epuindexng.com/). We cover the period of January 01, 2010 – November 30, 2022, and datasets are available for daily, weekly, and monthly frequencies. In this section, we offer to study the behaviour of the \(EPU_{t}^{{adj}}\)index in two ways. One, we provide some descriptive statistics and graphical representations of the index, and two, we complement one with some data analyses that attempt to connect the index with the predictability of relevant financial variables, such as exchange rates and stock prices, that are assumed to respond to uncertainties. We present the descriptive statistics in Table 2 for different daily, weekly, and monthly frequencies. Expectedly, we show that the dispersion of the index declines with lower frequency judging by both standard deviation and coefficient of variation. This observation is also evident in Figs. 1 and 2, and 3, where daily frequency shows greater dispersion than weekly and monthly, while the latter has the least dispersion. Even the formal tests for serial correlation and conditional heteroscedasticity in Table 3 show larger values of the test statistics for a higher (daily) frequency than a relatively lower (monthly) frequency. In addition, a closer look at the figures suggests greater uncertainties since 2015, coinciding with the period of oil price shock, economic recession, and the COVID-19 pandemic up to the period of the Naira redesign policy and its fallouts.

We also probe further to tease out any possible connection between Nigeria’s index and exchange rate by providing graphical evidence, as depicted in Fig. 4. We can find a somewhat positive connection between exchange rate appreciation and the index, a piece of evidence that is empirically investigated in the next section. In other words, higher economic uncertainties may drive higher depreciation of the Naira. Similarly, rising economic uncertainties discourage increased investments in the stock market as the two variables seem to be negatively related (see Fig. 5).

3.2 In-sample and out-of-sample predictability of the \(EPU_{t}^{{adj}}{\text{ index}}\)

3.2.1 The predictive model

We construct a predictive model distinctly for the realized volatilities of the exchange rate and stock returns where the \(EPU_{t}^{{adj}}{\text{ index}}\)serves as a predictor.Footnote 8 There is increasing evidence in the literature supporting the inclusion of news-based EPU indices in the predictability of financial series (see for a review, Al-Thaqeb and Algharabali 2019). Our predictive model theoretically aligns with Benanke’s (1983) observation that high levels of uncertainty incentivize businesses to postpone hiring and investment when personnel are expensive to hire and dismiss, or investment projects are costly to cancel. Similar to this, Myers and Majluf (1984) show how the pecking order theory can influence the stock market in the event of economic policy uncertainty. Moreover, the Arbitrage Pricing Theory effectively captures the relationship between uncertainty and market fundamentals such as stock returns and exchange rates. Thus, our predictive model follows these theories, particularly the Arbitrage Pricing Theory, as it provides the most accurate predictions of market fundamentals, including stock returns (see Kisman and Restiyanita 2015).

For empirical modelling, our predictive model follows the approach of Westerlund and Narayan (2012, 2015), which simultaneously accounts for some salient data features typical of high-frequency time series, such as persistence and conditional heteroscedasticity, as exhibited by our variables (see Table 3). Recent studies using this methodology have demonstrated its usefulness in improving predictability outcomes (see, for example, Narayan and Bannigidadmath 2015; Narayan and Gupta 2015; Phan et al. 2015; Bannigidadmath and Narayan 2016; Devpura et al. 2018; Salisu et al. 2019a&b). In addition, we account for possible shifts in the realized volatilities of the exchange rate and stock returns based on the day-of-the-week effect. If it exists, accounting for any inherent level shift in the series tends to enhance the predictability of outcomes (see Salisu et al. 2019a, b; among others). Given this background, the predictive model is written as:

where \(R{V_t}\) is a 22-day realized volatility of Nigeria’s exchange rate/stock returns computed at period t; \(EPUI_{t}^{{adj}}\) is the log-transformed news-based economic policy uncertainty index for Nigeria at the time t; \(DU{M_{i,t}}\) is the \({i^{th}}\)day-of-the-week dummy; \(\alpha\) is the intercept; \(\beta\) is the predictability coefficient; \(\gamma \left( {EPUI_{t}^{{adj}} - \psi EPUI_{{t - 1}}^{{adj}}} \right)\) is included to correct for any bias resulting from persistence effect \(EPU_{t}^{{adj}}\); \({\delta _i}\) is the coefficient for the day-of-the-week dummy; \({\varepsilon _t}\) is a zero mean idiosyncratic error term. Since we are using daily data, it will not be out of place to suspect the conditional heteroscedasticity effect (in fact, our preliminary test in Table 3 confirms this suspicion). Thus, to resolve this effect, we pre-weight Eq. (2) with the standard deviation of its residuals and, thereafter, re-estimate the resulting equation with the Ordinary Least Squares to obtain the Feasible Quasi-Generalized Least Squares estimates (see Westerlund and Narayan 2012, 2015).

In the final set-up, we evaluate the forecast performance of Eq. (3) relative to the benchmark (driftless random walk) model. We use the Clark and West (2007) [Clark-West] test to evaluate the forecast performance of the competing models since both are nested. A statistically significant positive value implies the outperformance of \(EPUI_{t}^{{adj}}\)-based model the benchmark model and vice versa for a statistically significant negative value. We utilize 75:25 data split for both the in-sample predictability and out-of-sample forecast evaluation. In the out-of-sample period, we consider 40-, 80- and 120- (daily) periods ahead of forecast horizons under a rolling window framework that allows for some time variation. The corresponding weeks and months are used for the predictability involving weekly and monthly frequencies, respectively.

3.2.2 Results and discussion

We begin our analyses with Eq. (3) which is the model without any additional (control) variable, and thereafter, we estimate an extended version that includes oil price volatility as a control variable. The connection between oil price and exchange rate (see, for example, Huang et al. 2020; Salisu et al. 2020) on the one hand and oil price and stock returns (see, for exampleNarayan and Gupta 2015; Salisu et al. 2019c, d) on the other hand is well established in the literature. Note that both variants of the predictability analyses involving daily data include the day-of-the-week effects while they are expectedly excluded for weekly and monthly frequencies. In the case of the former, all the differential intercept coefficients are statistically significant (see Table A2 in the appendix), indicating the existence of these effects in the behaviour of both exchange rate and stock returns. In Table 4, we present only the predictability coefficient of the EPU index under the two model scenarios (with and without an additional (control) variable) and for three different frequencies, daily, weekly and monthly. The full results are presented in the appendix (see Tables A2, A3, and A4 for the daily, weekly, and monthly frequencies, respectively).

We utilize the full data sample to establish the relationship between the EPU index and the selected financial series. For forecast analyses, 75% of the data sample is used for the in-sample estimation, while the out-of-sample forecast evaluation is determined from the balance. As expected, we show that the index significantly influences the behaviour of the exchange rate and the stock market in Nigeria (see Table 4). More specifically, the index positively relates to exchange rate return volatility for daily and weekly frequencies (in line with our observation in Fig. 4), while it is negative for the monthly frequency. In other words, for the positive association, we can conclude that higher uncertainties create negative signals in the domestic economy, which may discourage capital inflow and thus raise the level of currency depreciation (Krol 2014). The negative relation between the index and exchange rate volatility for the monthly frequency is not far-fetched, given that the official exchange rate is used in this study. In the case of Nigeria, which is characterized by managed floating exchange rate mechanism, the monetary authority intervenes at intervals to moderate any noticeable deviation between the official and “market-based” exchange rates. Therefore, any significant volatility in the exchange rate in the early days of a month can be moderated by the month-end with the intervention of the monetary authority. We, however, observe consistent results for the stock market since this market is largely market-driven and does not enjoy the kind of interventions extended to the foreign exchange market in Nigeria. Specifically, we establish a negative connection between the index and stock return volatility (as depicted in Fig. 5), indicating that higher uncertainties may discourage future investment in the stock market, thereby reducing trading activities and, by extension, market volatility. Our results for stock return volatility and the associated impact of uncertainty (EPU index) on investment support the findings by Baker et al. (2016) who equally establish a negative nexus between EPU and global investment, output and employment. In the same vein, empirical evidence by Iqbal et al. (2020) highlights negative influence of EPU on US-based firms’ performance. This is plausible, given the role of EPU on currency depreciation as shown in our results. Currency depreciation especially for import-dependent country such as Nigeria portend high cost, which could reduce firm’s profit margin. Given the foregoing, Dai et al. (2017) demonstrate that EPU index can affect currency exchange rates and equally has some predictive ability for return on investments in future exchange rates.

We also conduct some simple forecast analyses using the Clark and West (2007) measure of forecast evaluation since the competing (restricted and unrestricted) models are nested. We present the results in Tables 5 and 6, and 7 for daily, weekly, and monthly data frequencies, respectively. Our index offers more accurate forecasts for the examined financial series than the benchmark model. We observe greater forecast outcomes for the stock market than the foreign exchange market as the forecast outcome for the former consistently improves across the three data frequencies and over the forecast horizons, unlike the latter, where the benchmark model outperforms the index-based model at a lower frequency. As noted previously, the incessant interventions of the relevant authority in the foreign exchange market may limit the predictability of the index at a lower frequency during which such interventions are undertaken. In other words, investors in the stock market tend to monitor the state of macroeconomic conditions when making investment decisions. This outcome also aligns with the Arbitrage Pricing Theory, which assumes that individual stocks respond to macroeconomic risks. In sum, the outcome lends credence to the appropriateness and adequacy of the index in measuring uncertainties in Nigeria.

As a form of additional analysis and in response to the request by one of the reviewers, we also extend the evaluation of the predictive prowess of our proposed EPU index for Nigeria to inflation. We are considering two types of inflation in this case: (i) actual inflation, which is computed from the year-on-year percentage changes in monthly consumer prices, and (ii) inflation risk, which is calculated using the realized volatility of inflation based on a three-month rolling window. Most economic outlook reports are done on a quarterly basis, so the inflation risk that manifests within this quarter has a greater tendency to influence investor and business expectations about the future behaviour of inflation. Due to the unavailability of inflation data at higher frequencies, we can only conduct analyses on a monthly basis, unlike the stock prices and exchange rate scenarios. We present the results in Table 8 both for the in-sample and out-of-sample predictability. We find that a higher incidence of economic policy uncertainties tends to raise the level of inflation and inflation risk. This behaviour extends to the out-of-sample performance, where the consideration of the index improves the out-of-sample forecast results of inflation. Overall, the index offers useful predictive content for both financial and macro variables, and therefore, when constructing predictive models for these variables in the country of focus, we encourage the inclusion of the index to improve the forecast results and minimise any inherent bias in the estimation process.

4 Conclusion

Our effort in this study is to fill an obvious gap in the literature in the computation of economic uncertainty indices. It is generally observed that all the African countries are hardly captured in the existing indices, thus making it difficult to conduct related studies on Africa. With the increasing uncertainties associated with the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war and how such are projected to impact the African continent, the proposed EPU index will come in handy when making investment and policy decisions at least for one of the leading countries in Africa. This is the motivation for the study. Thus, as a preliminary step towards providing a platform that tracks the extent of uncertainties in Africa, we focus on its largest economy, Nigeria, while we hope to extend this exercise to other emerging economies on the continent in the foreseeable future.

Essentially, the economic policy uncertainty index involves prominent newspapers in Nigeria. We scrape their articles to identify relevant keywords, which are then used to construct the index. Consequently, we offer several analyses to test the predictability of the index, particularly for exchange rate and stock return volatility. We find that the index contains useful predictive contents that can be exploited to improve the out-of-sample forecast of exchange rate and stock returns, albeit with greater out-of-sample predictive power for the latter when a lower frequency is used. Overall, the index more prominently positively connects with the exchange rate, while it does so negatively with stock returns. In other words, higher uncertainties can cause the exchange rate to depreciate further, and similarly, it can discourage future investment in the stock market. The outcome aligns with the theoretical and empirical literature evidence regarding how uncertainties connect with economic and financial variables. Given that the proposed index is available at a high frequency, information about public sentiments on any policy decision in the country will come in handy for relevant authorities to review and process for further actions. Similarly, the results generated from testing the nexus between our index and some financial and macro fundamentals would serve as a useful guide to investors on significance of factoring policy uncertainty in their investment decisions, and to always exercise caution during heightened uncertainty in the country. Finally, future studies can extend the literature on Africa by constructing country-specific policy uncertainty index for some other African countries. Also, indices focusing on other measures of uncertainties such as geopolitical risk index, among others can be constructed for Africa given the rising geopolitical tension in the Western and Central Africa sub-regions.

Notes

Several empirical studies using these indices have provided evidence of their usefulness in the predictability of economic and financial series (see for a review, Al-Thaqeb and Algharabali 2019).

In selecting the newspapers for the construction of the index, a few criteria need to be considered. These include credibility, readership or audience, frequency of publication, and availability.

Web Scraping involves using software tools such as BeautifulSoup, Scrapy, Playwright, and Selenium to extract data from websites. It is used to scrape news articles from Nigerian newspapers’ websites and store them in a database for further analysis. We also consider sitemaps where it is possible to extract the URLs of news articles and automate the download of the articles. This method is faster and more efficient than web scraping or manual collection since it provides a structured way to access news articles. In addition, some Nigerian newspapers provide RSS feeds that can be subscribed to for automated updates on news articles. This method is used to download news articles automatically as they are published and store them in a database for further analysis. Finally, we also adopt the manual collection approach, which involves manually collecting newspapers and physically clipping or scanning relevant news articles. While this method is more time-consuming, it becomes necessary in cases where newspapers do not have digital versions or APIs.

The availability of consistent information on the relevant keywords determines this period. Nonetheless, the data scope enables us to evaluate the uncertainty associated with the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the global oil shock between 2007/2008.

Note that some of these newspapers have been in existence before the start date of the index data scope. However, information about the keywords was very scanty before 5/1/2010, with several gaps that obviously cannot be used for meaningful empirical analyses.

This is an important feature of daily frequency variables that connect with investors and practitioners, which has to be incorporated into the construction of the index to make it more realistic (see, for example, Narayan et al. 2021). This phenomenon has been largely validated in the finance literature, where it is assumed that the same information may have differing effects during the days of the week as the average daily return of the market is not the same for all the days of the week (see Drogalas et al., 2007).

References

Ahir, H., Bloom, N., Furceri, D.: The world uncertainty index (No. w29763). National Bureau of economic research (2022)

Al-Thaqeb, S.A., Algharabali, B.G.: Economic policy uncertainty: A literature review. J. Economic Asymmetries. 20, e00133 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2019.e00133

Aye, G.C., Kotur, L.N.: Effect of economic policy uncertainty on agricultural growth in Nigeria. Afr. J. Agricultural Resource Econ. 17(2), 106–114 (2022)

Baker, S.R., Bloom, N., Davis, S.J.: Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 131(4), 1593–1636 (2016)

Bannigidadmath, D., Narayan, P.K.: Stock return predictability and determinants of predictability and profits. Emerg. Markets Rev. 26, 153–173 (2016)

Bernanke, B.S.: Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. Q. J. Econ. 98(1), 85–106 (1983)

Caldara, D., Iacoviello, M.: Measuring geopolitical risk. Working paper, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board. (2019)

Clark, T.E., West, T.D.: Approximately normal tests for equal predictive accuracy in nested models. J. Econ. 138, 291–231 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2006.05.023

Dai, Y., Zhang, J.W., Yu, X.Z., Li, X.: Causality between economic policy uncertainty and exchange rate in China with considering quantile differences. Theoretical Appl. Econ. 24(3), 29–38 (2017)

Davis, S.J.: An index of global economic policy uncertainty (No. w22740). National Bureau of Economic Research (2016)

De Santis, R.A.: Unobservable systematic risk, economic activity, and the stock market. J. Banking Finance. 97, 51–69 (2018)

Devpura, N., Narayan, P.K., Sharma, S.S.: Is stock return predictability time-varying? J. Int. Financial Markets Institutions Money. 52, 152–172 (2018)

Drogalas, G., Athianos: Stergios and Bakas, George and George, Elekidis, Seasonalities in stock markets: The day of the week effect. June 26, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2515097 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2515097 (2007)

Faccini, R., Matin, R., Skiadopoulos, G.: Are climate change risks priced in the U.S. stock market? (No. 169). Danmarks Nationalbank Working Papers. (2021)

Huang, B.N., Lee, C.C., Chang, Y.F., Lee, C.C.: The dynamic linkage between oil prices and exchange rates: New global evidence. Empir. Econ. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01874-8

Iqbal, U., Gan, C., Nadeem, M.: Economic policy uncertainty and firm performance. Appl. Econ. Lett. 27(10), 765–770 (2020)

Kisman, Z., Restiyanita, S.: M. The validity of Capital Asset pricing model (CAPM) and arbitrage pricing theory (APT) in Predicting the Return of stocks in Indonesia Stock Exchange. Am. J. Econ. Finance Manage. 1(3), 184–189 (2015)

Krol, R.: Economic policy uncertainty and exchange rate volatility. Int. Finance. 17(2), 241–256 (2014)

Kumeka, T.T., Falayi, O.R., Adedokun, A.J., Adeyemi, F.O.: Economic policy uncertainty and exchange market pressure in Nigeria: A quantile regression analysis. Int. J. Sustainable Econ. 15(2), 135–166 (2023)

Myers, S.C., Majluf, N.S.: Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J. Financ. Econ. 13(2), 187–221 (1984)

Narayan, P.K., Bannigidadmath, D.: Are Indian stock returns predictable? J. Banking Finance. 58, 506–531 (2015)

Narayan, P.K., Gupta, R.: Has oil price predicted stock returns for over a century? Energy Econ. 48, 18–23 (2015)

Narayan, P.K., Iyke, B.N., Sharma, S.S.: New measures of the COVID-19 pandemic: A new time-series dataset. Asian Econ. Lett. 2(2) (2021). https://doi.org/10.46557/001c.23491

OECD: Africa’s integration into the global economy. In: Africa’s Development Dynamics 2018: Growth, Jobs and Inequalities. OECD Publishing (2018). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302501-6-en Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa

Ozili, P.K.: Sources of economic policy uncertainty in Nigeria: Implications for Africa. In: Managing Risk and Decision Making in Times of Economic Distress, Part A. Emerald Publishing Limited (2022)

Phan, D.H.B., Sharma, S.S., Narayan, P.K.: Stock return forecasting: Some new evidence. Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 40, 38–51 (2015)

Salisu, A.A., Akanni, L.O.: Constructing a global fear index for the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg. Markets Finance Trade. 56(10), 2310–2331 (2020)

Salisu, A.A., Adekunle, W., Alimi, W.A., Emmanuel, Z.: Predicting exchange rate with commodity prices: New evidence from Westerlund and Narayan (2015) estimator with structural breaks and asymmetries. Resour. Policy. 62, 33–56 (2019a)

Salisu, A.A., Isah, K., Akanni, L.: Improving the predictability of stock returns with bitcoin prices. North. Am. J. Econ. Finance. 48, 857–867 (2019b)

Salisu, A.A., Swaray, R., Oloko, T.F.: Improving the predictability of the oil–US stock nexus: The role of macroeconomic variables. Econ. Model. 76, 153–171 (2019c)

Salisu, A.A., Raheem, I.D., Ndako, U.B.: A sectoral analysis of asymmetric nexus between oil price and stock returns. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 61, 241–259 (2019d)

Salisu, A.A., Cuñado, J., Isah, K., Gupta, R.: Oil price and exchange rate behaviour. (2020)

Si, D., Zhao, B., Li, X., Ding, H.: Policy uncertainty and sectoral stock market volatility in China. Economic Anal. Policy. 69, 557–573 (2021)

Westerlund, J., Narayan, P.K.: Does the choice of estimator matter when forecasting returns? J. Banking Finance. 36(9), 2632–2640 (2012)

Westerlund, J., Narayan, P.: Testing for predictability in conditionally heteroskedastic stock returns. J. Financial Econometrics. 13(2), 342–375 (2015)

Xu, Z.: Economic policy uncertainty, cost of capital, and corporate innovation. J. Banking Finance. 111, 105698 (2020)

Yuan, M., Zhang, L., Lian, Y.: Economic policy uncertainty and stock price crash risk of commercial banks: Evidence from China. Economic Anal. Policy. 74, 587–605 (2022)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the research assistance received from Abeeb Olaniran, Sheriff Badmus, and Abdul Hameed Abdul Hakeem.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Pretoria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

Needless to say, the authors are responsible for any remaining errors in this version of the paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salisu, A., Salisu, S. & Salisu, S. A news-based economic policy uncertainty index for Nigeria. Qual Quant (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01886-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01886-x