Abstract

The intensity of between-school pupil mobility in Flemish regular primary education is measured for the first time, using enumerative data about a birth cohort. Given the lack of internationally established measures, several indicators representing the system’s, the pupil’s, and the school’s point of view are introduced. It turns out that the level of mobility is significant, as compared to other atypical events in pupils’ trajectories. The consequent importance of mobility as a nuisance factor in education research is discussed. The under-researched issue of school definitions is shown to have an impact on mobility measurement in Flanders and is discussed from the wider perspective of effectiveness research. Directions for future research about between-school pupil mobility are set out.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: the visibility of atypical trajectories through Flemish primary education

Flemish primary education’s vertical and horizontal stratification differentiates pupils’ trajectories, as at other levels of education and in most education systems (OECD 2020). It creates a standard specifying that the pupil enrols in a primary school in September of the calendar year of the sixth birthday (or, sometimes, earlier) and attends this school for up to six years, successfully following a curriculum designed to attain and preferably surpass the minimum attainment goals specified by the government. Deviation from this standard implies that the trajectory through primary education is less smooth than desired or limits the pupil’s future options. It means that the pupil experiences one or several of the following atypical events: entering primary education later than the standard age, repeating a grade, not attaining or being exempted from attaining the official list of goals, or changing primary schools.

1.1 Late entry and retention

From a European perspective (Eurydice 2011), delayed entry in Flemish primary education is relatively rare, but delay within primary education is frequent. This is consistent with the 5% of late entrants mentioned by Vandecandelaere et al. (2016) and the “one child out of six” repeating within primary education referred to by Goos et al. (2013). Official counts of retention in Flanders have been available since 1998 (JOP 2023; VMOV 2022a). Flemish grade retention research is embedded in the international research, with emphasis on the “causal” effect of retention as an individual “treatment” on subsequent outcomes (Goos et al. 2013; Demanet and Van Houtte 2016; Vandecandelaere et al. 2016). Within that particular scientific framework, finding positive effects of retention is difficult. Consequently, there is a gap (Juchtmans and Vandenbroucke 2013; OVSG 2015) between the recommendations in the scientific or policy- and practice-oriented literature and grade retention as a well-established practice, making it a subject of public debate.

1.2 Not attaining or being exempted from attaining the official minimum goals

Pupils successfully completing primary education are granted a certificate by the school (Eurydice 2022), giving access to mainstream secondary education—the so-called A-stream. This certificate is our closest proxy to what it means to be subject to and successful in reaching the official attainment goals. Using new statistics about the 2020 transition from primary to secondary education (VMOV 2022a), I estimate that 86% of pupils obtained the certificate. The remaining 14% can be partitioned according to the point of departure in primary education: roughly 5% came from the sixth grade, 3% from an earlier grade in regular primary education, and the remaining 6% from special education.

About 90% of pupils enter secondary education from the sixth grade (Van Landeghem 2021) and a large majority (19 out of 20) of those hold the certificate. During the past two decades, the achievement of this group has been a topic of official and public scrutiny via sample based assessments (STEP 2019; DS 2019).

Pupils who come from the fifth or a lower grade having neither a certificate of primary education nor a referral to special education can enter secondary education via the B-stream when they turn twelve (Eurydice 2022). They have been delayed in elementary education and have often been assigned an individualised curriculum in the course of primary education. This practice is not a topic of debate in Flemish educational policy.

The largest group of pupils entering secondary education without a certificate comes from special education. The curricula of Flemish primary pupils with officially certified special educational needs are exempted from the attainment goals imposed on the regular curriculum. Pupils in Flemish primary education are enrolled in either a regular or a special primary school (EASNIE 2020a). The corresponding breakdown of the enrolment statistics has been reported in the Statistical annual of Education at least since the end of the seventies (Van Landeghem and Van Damme 2002). Most pupils officially identified as having special educational needs attend the parallel pathway of special primary schools. Thus, the fraction of Flemish primary pupils not in an inclusive setting is among the highest in Europe (EASNIE 2020b). This has been a longstanding topic of educational and political controversy (VR 2019; D'Espallier 2016; BS 28.08.2014), intensified by the ratification in 2009 by Belgium of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

1.3 Changing primary schools

The possibility to change schools at any point in an educational trajectory is embedded in the “grammar” (Tyack and Tobin 1994) of school systems in Belgium: the freedom to organise education and freedom of school choice are constitutional rights (Eurydice 2022). That may explain why, in several ways, between-school pupil mobility in Flanders is taken for granted.

Pupil mobility did receive some attention in recent scientific analyses of Flemish education. For example: Goos et al. (2013) examined the relationship between first grade retention and subsequent mobility between regular primary schools, considering it—together with grade retention and transitioning to special education or the B-stream of secondary education—as a marker of a less favourable trajectory. Also, Dockx et al. (2017) studied the relationship between pupil mobility in primary education and achievement in mainstream early secondary education, noting that mobility had not appeared as an explanatory factor in educational research in Flanders until then. In a study of predictors for using various pupil guidance programs, Bodvin et al. (2019) attached importance to whether the program implied a school change. Finally, in a follow-up study of the Flemish part of PIRLS 2016, pupil mobility was the main cause of attrition between the fourth and sixth grades (Van Landeghem et al. 2019). However, none of these studies offers a comprehensive view of the intensity of mobility in Flemish primary education.

The Flemish administration provides authorised school staff with access to indicator values for their school (VMOV 2022b). Some describe aggregate pupil mobility, through the lens of two consecutive school years. But no publicly available data support a description of pupil mobility in Flanders. The Statistical annual of Flemish education is a case in point. Whereas indicators of grade retention have been included for more than a decade, the annual lacks information about pupil mobility (VMOV 2022a).

The situation regarding internationally comparative quantitative data is similar. The OECD, for example, considers the “share of repeaters” a relevant educational indicator, but does not refer to any indicators reflecting between-school pupil mobility (OECD 2018a, 2021). Similarly, the Eurostat (2022) database, in tables based on the annual UOE data collection (UNESCO-UIS/OECD/Eurostat 2020), contains sufficient information to derive indicators of grade retention in primary education, but lacks any basis for estimating between-school pupil mobility.

1.4 Aim and overview of this study

Quantitative data about school changes within Flemish primary education are scarce, in contrast with other atypical events. Therefore, this study aims to quantify mobility in Flemish primary education, which serves as an example of a market-based education system. To that end, after a description of the theoretical motivation for this study in Sect. 2, detailed research questions are formulated in Sect. 3. Section 4 specifies the data available to answer these questions. Before the findings are set out (Sect. 7), the issue of between-system transitions is accounted for (Sect. 6) and a pragmatic approach is proposed to solve the problem of identifying stable real primary schools—as opposed to short-lived administrative entities—from the data (Sect. 5). Finally, four topics are discussed in Sect. 8: the intensity of between-school pupil mobility in Flemish primary education, the impact of pupil mobility as a nuisance factor in education research, the question of how to define schools, and the role of between-school pupil mobility in the functioning of education markets.

2 Theoretical background

Education markets appear to need between-school pupil mobility. Jabbar (2015), for example, refers to transfers between schools as an objective measure of competition. Also, Leist and Perry (2020) were able to identify education markets in Hamburg by analysing structural pupil transitions between primary and secondary schools. Thus, in a market-based education system, the main question is not whether between-school pupil mobility is “helpful or harmful” (Welsh 2017; Rumberger 2015),Footnote 1 but rather whether and how it should be managed. An additional question is whether pupil mobility is a useful indicator of proper market functioning. Of course, one may also question whether market principles are the proper way to organise an education system (Hofflinger and von Hippel 2020; Hofflinger et al. 2020; DeAngelis 2019; Roda and Wells 2013). But that is a debate in a different league, as illustrated before in the case of Belgium, where the freedom to organise education and freedom of school choice are constitutional rights (Eurydice 2022). Thus, this debate goes far beyond the issue of pupil mobility and the scope of education research.

Despite the importance of pupil mobility for education markets, the scientific literature looking into both topics together is scarce. In fact, the literature about the functioning of education markets tends to focus on schools (Haber 2021; Pearman 2020) or, when pupils and parents are involved, on school or track choice rather than on mobility (Kosunen et al. 2020; Candipan 2020; Herskovic 2020; Garrouste and Zaiem 2020; Hofflinger et al. 2020; Roda and Wells 2013). Often, a central question is how school choice can be regulated to balance it with equity as well as enhancing effectiveness (OECD 2019; Boeskens 2016). The studies about mobility mostly focus on the effect of mobility on moving pupils (Stein et al. 2021; Voight et al. 2020; Larsen 2020; Cordes et al. 2019) and, rather seldom (Welsh 2017), on the destabilising effects of mobility on schools (Taghizadeh 2020; Rumberger 2015; Hanushek et al. 2004) but not on schools as competitors.

A first consequence is that the exact role of between-school pupil mobility in the shaping and maintaining of education markets is not clear. Is the mere fact that mobility is allowed and feasible, sufficient to make a market work? Or is there a threshold of actual transfer activity below which competitive pressure on schools disappears? And is there, at the other end of the scale, an upper threshold above which the intensity of pupil mobility becomes harmful for the education system? Answers to these questions determine whether pupil mobility is a relevant indicator of market functioning. They require insight in the internal structure and functioning of education markets that we do not possess at present. In a simple picture of school improvement through market forces, schools are interchangeable in that they offer similar trajectories to comparable pupils, who are free to move between schools (Herskovic 2020). This head-on competition keeps schools on their toes to provide education of the highest possible quality (Hofflinger et al. 2020; Welsh 2017). Schools that cannot keep up, quickly loose their pupils and close (DeAngelis 2019). According to this view, school closures, caused by competition, would be an important source of pupil mobility (Taghizadeh 2020; Larsen 2020). However, this model does not fit Flemish education, where there is a strong tendency to sort pupils into homogeneous groups. That is achieved with tracking and grade retention, but also via the freedom to organise education, which essentially means that the Flemish government can determine what a school should achieve when it offers a particular track, but not how. Consequently, schools have the option to deal with competitive pressure by carving out a niche market for themselves, catering for a specific segment of the pupil population (Haber 2021; Leist and Perry 2020). This broadens the educational supply, making it easier for pupils and parents to find a “right fit”, not only in an educational sense (Garrouste and Zaiem 2020; OECD 2019), but also, more controversially, in socio-economic terms (Haber 2021; Leist and Perry 2020). It also drives between-school pupil mobility, as pupils and parents may become aware of a more “fitting” niche in the course of the trajectory and are free to move (Van Landeghem 2022). Thus, whereas allowing mobility is conventionally thought to drive competition (Welsh 2017), different types of competition probably also keep up mobility. Also, we know little about the relative importance of these two mechanisms—improvement by direct competition versus pressure relief by market segmentation (Haber 2021; DeAngelis 2019)—in actual education markets.

Secondly, it remains unclear whether or how the disadvantages of school change for individual pupils can be reconciled with the apparent need for mobility in education markets. On the one hand, market forces in education are claimed to be beneficial (DeAngelis 2019) and the necessery competitive pressure between schools is assumed to be driven by pupil mobility (Welsh 2017). On the other hand, a large part of the scientific literature points at negative consequences for the educational outcomes of individual pupils changing schools (Ford 2023; Welsh 2017; Rumberger 2015). Thus, it appears that a minority (consisting of those changing schools) is paying a price to enable all involved to enjoy a better education system. The implication is that education markets are currently functioning suboptimally, from an ethical point of view, and that there is room for improvement.

The scientific literature does not claim that every single school change has detrimental effects for the pupil involved. Rather, it posits that there are often short-term difficulties caused by the change of environment (Hanushek et al. 2004), but that the net effect in the long term depends on whether the receiving school is “better”, in a narrow sense of a higher performing school or in the broad sense of providing a better fit between pupil and school (Welsh 2017; Rumberger 2015; Hanushek et al. 2004). This prompts the question whether unpromising between-school pupil movements can be prevented and unavoidable ones improved (Rumberger 2015) while keeping the benefits of the education market.

Thirdly, there are open questions about potential conflicts of interest faced by schools that operate in an education market. A school may choose to encourage, discourage or remain indifferent with regard to the entry or exit of particular pupils. The question then is whether its responsability for the pupil’s educational trajectory is necessarily in line with its obligation to survive under competitive pressure, and if not, how such a conflict is handled (OECD 2019; Rumberger 2015). In addition, between-school pupil mobility implies that several schools may contribute to one structural stage, such as the primary or the secondary education trajectory of a given pupil. This raises the question whether schools should be expected to assume a collective responsibility (across schools) for complete trajectories, however fragmented (Rumberger 2015). If so, the subsequent question is how such a collective role can be made compatible with their roles as competitors in a local market (Armstrong and Ainscow 2018).

The rationale behind the present study is that an examination of these questions about the role of between-school pupil mobility in education markets should start from basic descriptive evidence. Such evidence correlates mobility measures with other descriptive characteristics across education systems, across local markets within education systems, or across schools. The present study addresses the current lack of suitable mobility measures by developing a set of indicators and illustrating their use in the description of mobility for a Flemish birth cohort in primary education.

3 Research questions

The substantial parallel track of special primary schools is a peculiarity of Flemish education, which creates three types of between-school transfer: regular to regular, special to special, or involving a regular and a special primary school. The latter type is specifically regulated, involves intensive consultation, and is therefore highly visible (Eurydice 2022; EASNIE 2020a). In contrast, there is little awareness of between-school movements within special education. Anyway, school changes involving at least one special primary school have in common that they are rather specific to the Flemish system. Therefore, this study focuses on the quantitative description of movements between regular schools, which is expected to be more useful for comparison with other education systems.

Administrative data about pupils’ positions are collected once per school year (VMOV 2022a). Accordingly, the present study is limited to year-to-year mobility, leaving multiple changes per year or the difference between end-of-year and within-year transitions (Stein et al. 2021; Rumberger 2015) outside its scope.

Given the lack of internationally established indicators, pupil mobility will be viewed from different angles, corresponding to the three main levels of actors in education systems (OECD 2021): the system, the school, and the pupil.

3.1 System’s point of view

To quantify between-school pupil mobility from the system’s point of view, it appears useful to focus on year-to-year transitions for several reasons. First, counting transitions and distinguishing between inter- and intra-school transitions is independent of detailed assumptions about a school system and does not require complex data. It is sufficient to have an education system structured in terms of school years and schools, which is common, to collect administrative data linking pupils to schools within a school year, and to maintain pupil identifiers across pairs of consecutive school years. Interesting between-system comparisons become possible as these conditions are met in an increasing number of contemporary education systems. Secondly, if pupil mobility is essential for the functioning of an education market (Welsh 2017), education policy concerning mobility will focus on mitigating transition effects and guaranteeing positive long-term effects of the school change, for example, by counseling and by enabling cooperation between schools (Rumberger 2015). Budgeting for support capacity requires information about the number of transfers per year. Thirdly, a time series of the yearly number of between-school pupil transfers may provide a simple tool to monitor change in an education market.

Specifically, this study addresses the following questions regarding pupil mobility from the system’s point of view.

[SysNum] How large is the number of transitions of pupils from one regular primary school to another, compared to the number of transitions between the regular and the special track?

What is the prevalence of between-school transitions …

[SysPre] … among transitions within regular primary education?

- [SysPrePro]

… among transitions with promotion?

[SysPreProG] … among transitions with promotion, per (successfully finished) grade?

- [SysPreRet]

… among transitions with retention?

[SysPreRetG] … among transitions with retention, per grade?

3.2 Pupil’s point of view

From a pupil’s perspective, a school change is an important event that interacts with other experiences along their trajectory, making the number of between-school transitions in the individual trajectory a variable of interest. Against the background of the parallel tracks in Flemish primary education, there are three types of trajectories: always in regular primary, always in special primary, or crossing the boundary between the tracks. To facilitate comparability with other education systems, the question is focused on trajectories completely within regular education.

Specifically, this study answers the following questions regarding pupil mobility from the pupil’s point of view.

[PupDis] How many times does a pupil who always attends regular primary education change schools?

[PupCon] Is the distribution of the number of school changes in the regular primary education trajectory different depending on whether the pupil experiences other atypical events (late entry, retention, early leaving)?

3.3 School’s point of view

There are several angles to describe between-school pupil mobility from the perspective of a school, for example: by using mobility data to characterise its role in the school market, by counting transitions from and to the school in order to plan for support capacity, by focusing on the composition and stability of its population. The first angle requires the demarcation of local school markets (Leist and Perry 2020) and the creation of a typology of school roles. That task is outside the scope of this study, which aims to provide a simple picture of the intensity of pupil mobility in Flemish primary education.

The second and third angles are made concrete as follows.

[SchPre] What is the prevalence of transitions to another regular primary school among all within-primary year-to-year transitions originating from this regular primary school?

[SchCore] How many years of education are provided by this school to pupils outside its core, as a share of the total number of years of education delivered—the core consisting of the pupils who start as well as finish their primary education in this school?

In answering these questions, the amount of variation between schools will be a point of interest (Rumberger 2015).

4 Data

I specified a data set tracing the trajectory through Flemish primary education of every pupil born in 1999Footnote 2 within a window of ten school years (2004–2005 to 2013–2014). In total, 410,458 years of primary education were delivered to those 69,361 pupils, via 3272 schoolsFootnote 3 (Tables 1 and 2). The yearly registration of an enrolled pupil consists of a school identifier and a categorical position variable: the six grades of regular primary education plus special primary education as a seventh category.

Table 1 offers a descriptive view of the data set. It is a simple representation of the passage of the birth cohort through primary education that can partly be obtained also by combining data from consecutive issues of the Statistical annual of Flemish education. As such, the table shows a familiar pattern (Van Landeghem and Van Damme 2004). Most members of the cohort pass through regular primary education in six school years, from grade 1 to grade 6, having entered at age six. The cohort takes essentially four years to pass through a given grade: a subgroup lags one year behind, and there are smaller groups one year in advance and two years behind. Some pupils (about 6%) enter late, but the group lagging behind increases considerably through grade retention during primary education (about 17%). The retention rate per grade decreases with the grade number, from a high rate in grade 1 (more than 7%) to near zero in grade 6. This has been a persistent characteristic of retention in Flemish primary education for decades (VMOV 2022a; Van Landeghem and Van Damme 2002). Special education enrols 2.6% of the six-year-olds, but its weight triples in the course of primary education. Finally, the significance of the pupil flow from the fifth or lower grades directly into the B-stream of secondary education, at about 3% of the cohort, is apparent in the decrease between the ages of eleven and twelve of the number of pupils lagging behind. Table 1 does not show, again analogous to the Statistical annual, information about the primary education certificates or about between-school mobility.

Table 2 shows the number of schools involved in the primary education of the cohort, per type (regular or special) and school year. A point of interest is that the total number of schools involved (3272) is considerably larger than the highest number (2905) in any particular school year. Specifically, in the interval of six years when the main part of the cohort moves from the first grade in regular primary education (2005–2006) to the sixth (2010–2011), the number of regular primary schools varies between a minimum of 2518 (sixth grade, 2010–2011) and a maximum of 2683 (fourth grade, 2008–2009). This suggests a rather dynamic school set or a problem with the stability of school identifiers. At present, little is known about the intensity of the dynamics (school entries, exits, mergers, splits) in Flemish education provision. But there is anecdotal evidence of two kinds of issues with the administrative school identifiers. First, at the system level, school identifiers may change for purely administrative reasons, that have no relation to the schools as they are perceived by parents and pupils. Secondly, at the school level, multiple school identifiers may be used to artificially partition schools, in order to maximalise incoming resources. Thus, in an analysis of between-school pupil mobility, it seems prudent to account for the difference between short-lived administrative schools and stable real schools.

5 Real schools versus administrative schools—an additional research question

Administrative fragmentation of real schools into smaller or shorter-lived units may lead to overestimation of pupil mobility. Therefore, an additonal question arises:

-

What is the impact of the difference between real and administrative primary schools on indicators of between-school pupil mobility in Flanders?

The topic of defining schools is complex and interesting. But in this study, the shortcomings of the administrative school definition are mainly a nuisance. Therefore this problem is approached pragmatically, solving it not completely but perhaps sufficiently. First, a simple clustering procedure (Appendix) is applied to join together administrative schools into real schools via pupil trajectory clusters. Secondly, the scope of the clustering procedure in terms of the fraction of administrative schools involved, its impact on the number of schools per school year (as in Table 2), and its effect on the distribution of the school size are described (Sect. 7.1). Thirdly, administrative schools within reach of the clustering procedure are replaced with real schools in the calculation of the mobility indicators. Fourthly (Sect. 7.5), the impact of this replacement on the indicators as well as its efficacy are assessed.

6 Mobility between education systems

Pupils move between Flemish education and the Dutch system (using the same language of instruction), the education system of the Communauté française (serving the French speaking pupils of Belgium), and other education systems. An approximate filter identifies about 7% of the trajectories as intersecting with another education system, leaving 64,389 pupils with completely visible trajectories. They represent 395,697 (96%) of the 410,458 years of education in the data set, and 331,308 within-primary year-to-year transitions.

In answering the research questions from the system’s point of view the specifics of the relationship between the Flemish education system and neighbouring systems will be set aside by focusing on the completely visible trajectories. Also, when treating the questions from the pupil’s point of view, the special group of pupils moving between systems during primary education will be left out.

7 Results

7.1 Real schools

7.1.1 Clustering

The clustering procedure affects 2657 (88%) of the 3024 administrative regular schools, yielding 2220 real regular schools (Table 3). The remaining 367 (12%) administrative regular schools, on which the procedure does not get any hold, delivered only 13,866 (4%) of the cohort’s 382,827 years of regular education. The distribution of the cluster size in Table 4 shows that 1851 of the administrative schools are confirmed as real schools, representing 83% of the 2220 real schools found by the clustering procedure. Table 3 also shows that the set of real schools is stable: their total number (2220) is equal to the highest number in any particular school year; in addition, during the central six-year period of 2005–2006 to 2010–2011, nearly all schools were involved in the cohort’s education. What remains of potential school dynamics is concentrated in the set of 367 administrative regular schools not reached by the algorithm.

7.1.2 School size

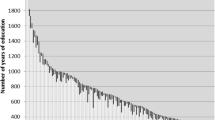

Figure 1 summarises how the clustering affects school size, expressed as the number of years of education provided to the cohort. Tiny schools—with fewer than 30 years of education—are almost completely eliminated from the pool of schools touched by the clustering algorithm.

Number of years of education delivered to the 1999 birth cohort per regular primary school; relative frequency distribution before and after clustering. Left: school involved in clustering, 368,961 years of education delivered by 2657 (before) / 2220 (after) schools. Middle: schools not involved in clustering, 13,866 years of education delivered by 367 schools. Right: all schools, 382,827 years of education delivered by 3024 (before) / 2587 (after) schools

7.2 Pupil inter-school mobility: system’s point of view

At 17,056 (Table 5), the number of between-school transitions within regular primary education in the 1999 birth cohort is more than five times the number of transitions (3115) from a regular to a special primary school, the most formalised and acknowledged type of between-school transition in Flemish primary education (research question [SysNum]). In 5 to 6% of the year-to-year transitions within regular primary education, pupils change schools ([SysPre]). At 20%, the prevalence of school changes among transitions with retention is four times higher than among transitions with promotion ([SysPreRet], [SysPrePro]).

The contrast between retention and promotion persists when viewed per grade. The prevalence of between-school transitions among transitions with retention varies modestly around the 20% mark, between 18% (in grade 1) and 23% (grade 5)Footnote 4 (question [SysPreRetG]). For transitions with promotion also, these prevalence rates do not stray far from the overall 5% value, with a minimum of 4% for promotions from grade 5 to 6 and a maximum of 6% from grade 2 to 3 ([SysPreProG]).

7.3 Pupil inter-school mobility: pupils’ point of view

Among the 64,389 pupils of the 1999 birth cohort who spent their primary education years completely within the Flemish system, 59,026 (92%) were always enrolled in the regular track. A majority of 80% of those 59,026 pupils never changed schools in the course of primary education. About 15% changed schools once, 5% twice or more (Table 6, question [PupDis]).

To answer research question [PupCon], the set of 59,026 pupils can be divided in four non-overlapping subsets and a small rest group (of less than 1%). The largest subset (covering 82% of the whole) consists of the pupils who entered primary education on time or in advance and completed the six grades in six school years. It approximates the subset of pupils who, leaving aside potential school change, have had a standard trajectory, as described in the introduction. Among pupils with this main type of trajectory, school change is less prevalent than in the whole set: about 84% attended a single school, 12% changed once, less than 4% changed twice or more. The second largest subset (10%) contains the pupils who completed the six grades in seven years. Among these retained pupils, school change is considerably more prevalent than in the whole set, with only 59% having never changed schools, 29% having changed once, and nearly 13% twice or more. The third largest subset (4%) consists of the pupils leaving primary education at the end of the fifth or fourth grade. Again, those pupils tend to change schools much more often than their peers in the main group. Finally, the fourth subset (less than 3%) represents those who delayed entry into primary education by one year, but completed the six grades in six school years. Late entry is also associated with a higher incidence of school changes, but with 73% attending a single school, 21% changing once, and 6% changing twice or more, the difference with the whole set is less pronounced than for the subsets with retention or early leaving.

7.4 Pupil inter-school mobility: schools’ point of view

Though incomplete, the set of 2220 real regular primary schools (Table 3) is expected to provide a more accurate basis to describe between-school pupil mobility from the perspective of a school than the complete set of schools, which includes the remaining administrative schools.

The prevalence of transitions to another regular primary school among all within-primary year-to-year transitions originating from a given regular primary school is on average, a bit less than 5% (in line with Table 5, see also Table 8). But the average value does not adequately describe the distribution of this prevalence rate. With a difference of almost 14 percentage points between the 2.5th (0.0%) and 97.5th (13.8%) percentiles, the burden of school mobility is not equal across schools (research question [SchPre]).

In total 36,961 years of education (Table 3) were delivered to the 1999 birth cohort by the 2220 real regular primary schools. As every year of education refers to a given pupil and school, the relationship between pupil and school—whether the pupil belongs to the school’s core group, is an early leaver, a late entrant, or a passer-by—partitions the set of years of education, as shown in Table 7. Thus, the weighted average of the fraction of years of education provided by a school to pupils outside its core is 22% (question [SchCore]). The variation of this fraction between the schools is considerable, as illustrated by the distribution in Fig. 2 and by the difference of about 50 percentage points between the 2.5th (4.5%) and 97.5th (54.7%) percentiles.

Partition of the set of real regular primary schools according to: the number of years of education provided by the real regular primary school to pupils outside its core, expressed as a share of the total number of years of education delivered. Distribution of the share, 2.5th percentile: 4.5%; 25th percentile: 13.8%; median: 20.8%; 75th percentile: 30.5%; 97.5th percentile: 54.7%

7.5 Real schools versus administrative schools: impact of the clustering process on indicators of pupil mobility

As demonstrated earlier (Sect. 7.1), the clustering algorithm reduces the intensity of school dynamics (Table 3) and the number of small schools (Fig. 1).

At 10% (Table 8), the estimated prevalence of between-school transitions within regular primary education based on administrative schools is four percentage points higher than the estimate of 6% based on real schools (Table 8, see also Table 5). The distinction between administrative and real schools matters more for transitions with promotion (10% versus 5%) than for transitions with retention (21% versus 20%). The pragmatic clustering procedure does not eliminate all instances of fragmentation from the administrative schools. The third column of Table 8 provides an approximateFootnote 5 lower limit of the mobility prevalence rate. It is about one percentage point below the estimate based on real schools.

Similarly, the distribution of the number of school changes per pupil reported in Table 6 can be compared with the distribution based on the administrative schools and with a limiting distribution ignoring mobility between the administrative schools that remain after clustering. The distribution based on the administrative schools shows higher mobility, with only 65% of the pupils never changing schools, in comparison with 80% according to the distribution after clustering (Table 6), which is close to the approximate limit of 81%.

The left panel of Fig. 3 shows that a quarter of the 2657 administrative schools reached by the clustering procedure delivers almost all of its years of education (> 95%) to pupils leaving early, entering late or passing by (Table 7). This anomaly disappears after clustering. As not all administrative schools are reached by the clustering algorithm (middle panel of the figure), schools with a very small core are not completely eliminated. But their fraction is reduced from nearly 30% to well below 10% (right hand panel).

Fraction of years of education not delivered to core pupils; variation between regular schools; relative frequency distribution before and after clustering. Left: schools involved in clustering. 2657 (before) /2220 (after) schools. The relative frequency histogram of the 2220 schools (after clustering) represents the same data as the absolute frequency histogram of Fig. 2. Middle: schools not involved in clustering, 367 schools. Right: all schools, 3024 (before) / 2587 (after) schools

8 Discussion

8.1 Intensity of between-school pupil mobility in Flemish regular primary education

The intensity of between-school pupil mobility within Flemish regular primary education is significant. First (research question [SysNum]), the number of movements is more than five times the much debated number of transitions from a regular to a special school. Secondly (question [PupDis]), 15% change primary schools once, 5% twice or more among the pupils who always attend the regular track. In comparison, about 17% experience delay through grade retention in primary education.

There are no international mobility indicators to compare these results with. Approximate comparisons with measures from other systems can be achieved, on a case by case basis. Limited evidence suggests, for example, that the mobility of pupils in the higher grades of primary education in parts of England (Goldstein et al. 2007) is roughly similar to the mobility of their Flemish peers. In contrast, between-school pupil mobility in U.S. primary education appears to be considerably more intensive. Princiotta et al. (2006), as cited by Welsh (2017), found that 66% of U.S. pupils changed schools between kindergarten and fifth grade, as compared to the 20% between the first and sixth grade in Flemish regular primary education (Table 6). As a third example, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2010), as cited by Welsh (2017), reported that “roughly 12% of schools had high rates of mobility with more than 10% of elementary students leaving by the end of the school year”. In comparison, among the 2220 real regular primary schools identified here (Table 3), more than 18% had high rates of mobility, that is, more than 10% of between-school transitions among all their within-primary transitions. This seems to indicate that the distribution of school-level mobility rates in Flanders is different from the U.S.

8.2 Between-school pupil mobility as a nuisance factor in research

Between-school pupil mobility can be a nuisance in longitudinal research (Heck et al. 2022). Two research designs from the Flemish context illustrate this. The first was used recently to assess the progress in reading comprehension of the pupils involved in the Flemish part of PIRLS 2016 (Van Landeghem et al. 2019), by conducting a follow-up measurement in the sixth grade of the same school sample. According to the 1999 birth cohort data, about 81% of the primary education trajectories is represented via this design. Among the lost 19%, seven percentage points are due to pupil mobility between the two measurements. This was unexpected at the time and provided a motive for the present study. Secondly, the current Flemish government plans to yearly observe every pupil in the fourth and sixth grade via standardised tests (VR 2019). In the 1999 cohort, about 88% of the primary education trajectories would be accessible via this design, seven percentage points of which would refer to pupils who change schools in between. The latter is an issue as the stated aim of the tests is to make schools accountable for learning progress between the two grades.

Longitudinal aspects of educational effectiveness analyses do not always get the attention they deserve. Whenever the relationship between a school characteristic and pupil outcomes is examined, the question of the stability of the school characteristic and the duration of the pupils’ exposure arises. In an analysis of the effects of school-wide positive behaviour support in Denmark, Jensen (2021) does give some attention to stability via the timeline of the prevention program in the schools and to exposure by excluding “feeder” schools that do not cover compulsory education completely. In contrast, and as an illustration in the Flemish context, consider a design where every pupil in the first, third, and sixth grade of a sample of regular primary schools is observed in a given school year. In the 1999 birth cohort 99, 94, and 91% of the years of regular primary education consumed up to the first, third, and sixth grade had been delivered by the pupil’s current school. These fractions, expressing exposure to the current school environment, vary between schools: from 91 to 100% (2.5th and 97.5th percentiles, first grade), from 80 to 100% (third grade), from 73 to 100% (sixth grade). This cross-sectional design has been used by Vanbuel and Van den Branden (2021) to examine whether schools with whole-school language policies have higher pupil language learning achievement. It lacks the longitudinal perspective needed to register the variation in exposure duration. Many such studies relating school characteristics to pupil outcomes have been published without attention to pupil mobility and exposure duration (for example Shapira-Lishchinsky 2021; Elacqua et al. 2021; Šťastný et al. 2021).

8.3 Defining schools

As discussed in the previous section, between-school pupil mobility can interfere with educational research analyses. In this study (Table 8, Fig. 3), it has been shown that ambiguity about school definitions can interfere with the measurement of between-school pupil mobility. This is only one instance of the wider issue of how to define schools, which has received remarkably little attention. For example: in a series of 58 consecutive articles in the journal School Effectiveness and School Improvement (Volume 30, Issue 3 to Volume 32, Issue 2), the school is involved as a unit of interest in about two thirds (37) of the studies. But only in four of those (Elacqua et al. 2021; Pietsch et al. 2020; Schmid et al. 2020; and Anderson 2020), the definition of schools is problematised in some way. Also, the large sample-based international studies organised by the OECD or the IEA rely on country-specific school definitions (OECD 2018b; Martin et al. 2020). The potential impact on cross-country analyses which include the school level (as in: OECD 2019, 2020; Shapira-Lishchinsky 2021; Šťastný et al. 2021) is currently unexplored.

In ongoing research, I use the simple clustering procedure applied in this study as a starting point, to develop a method to construct schools by combining an explicit school definition with enumerative trajectory data.

8.4 Future research

The precise role of pupil mobility in a market-based education system is not clear at present. For example (Sect. 2), it is unclear whether or how the disadvantages of school change for individual pupils can be reconciled with the apparent need for mobility in education markets. The expected beneficial effects of market forces on educational provision (DeAngelis 2019) via competitive pressure between schools is assumed to be driven by pupil mobility (Welsh 2017). But most of the scientific literature points at negative consequences for individual pupils changing schools (Ford 2023; Welsh 2017; Rumberger 2015). These current studies about mobility mostly focus on the effect of mobility on individual moving pupils, other things being equal (for example Stein et al. 2021; Voight et al. 2020; Larsen 2020; Cordes et al. 2019). This is a narrow approach of the issue which contributes little to policymaking, as policy changes are supposed to change the educational environment. I therefore propose two alternative avenues of future research. First, as a part of an ongoing research project, I plan to use pupil trajectory data to delineate local education markets and analyse their internal structure, in terms of distinct roles of schools within these markets.With reference to the present study, such an analysis could answer the question of which part of the variation across schools of the intensity of pupil mobility (Fig. 2) is explained by characteristics of the local education market and by the role of the school within its market. Secondly, for the Flemish birth cohort of 1999, the prevalence of school changes among transitions with retention was four times higher than among transitions with promotion (questions [SysPrePro], [SysPreRet]). This finding is remarkable, but we lack the knowledge to explain it. Along with Gasper et al. (2012), Stein et al. (2021), and Haber (2021), I call for “more qualitative studies to provide on-the-ground and fine-grained possible explanations of student mobility trends and how students and families experience student mobility in a practical sense” (Welsh 2017), to gain insight in the decision processes behind transfers.

8.5 Conclusion

In this study, the intensity of between-school pupil mobility in Flemish regular primary education has been measured for the first time. As there are no internationally established measures of between-school pupil mobility, several indicators representing the system’s, the pupil’s, and the school’s point of view have been proposed. This can be a starting point to remedy the absence of mobility data in international educational databases. Basic quantitative mobility data can be a tool to raise awareness among all stakeholders in education about between-school changes as potentially disrupting events in pupils’ trajectories. Researchers also need such data to account for mobility as a nuisance factor in their research designs. Moreover, comparisons of mobility indicator values across education systems, across local markets within education systems, and across schools may yield new insights into the functioning of market-based education systems in future research. Finally, this study also draws attention to the often neglected issue of the definition of schools.

Notes

“Educational policy makers and researchers make divergent assumptions regarding the effects of student mobility and there is still much disagreement on whether student mobility is a helpful or harmful phenomenon” (Welsh 2017, p. 476). “There is widespread concern among students, parents, educators, and policymakers about whether student mobility, especially frequent or chronic student mobility, is helpful or harmful to students’ school performance” (Rumberger 2015, p. 2).

The aggregate enrolment data, as reported in the Statistical annual of Flemish education, mark 2013 as a turning point in long-established trends of grade retention in primary education and the weight of special primary education (Van Landeghem et al. 2019). The 1999 birth cohort has been selected because its passage through primary education largely predates this trend break, avoiding, amongst other things, the transitional effects of the introduction of the M Decree (BS 28.08.2014).

The schools in question are the units designated as “vestigingen” in the administrative data. Each one of those refers to one particular site. Some are part of multi-site schools.

At 29%, the prevalence rate in sixth grade is higher. But this percentage is based on a small number of pupils (132), consistent with the low retention rate in the sixth grade.

The lower limit is obtained by ignoring mobility within the set of administrative schools which remained out of reach of the clustering procedure. It is an approximate because a more refined clustering procedure would not necessarily leave the current real schools completely intact.

References

Anderson, D.: Exploring teacher and school variance in students’ within-year reading and mathematics growth. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1618349

Armstrong, P.W., Ainscow, M.: School-to-school support within a competitive education system: views from the inside. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1499534

Bodvin, K., Verschueren, K., Struyf, E.: Different pathways to student guidance in mainstream primary and secondary education: results from a parent survey. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2018.1469100

Boeskens, L.: Regulating Publicly Funded Private Schools: A Literature Review on Equity and Effectiveness. OECD Publishing, Paris. OECD Working Papers No. 147 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1787/5jln6jcg80r4-en

BS: 21 maart 2014—Decreet betreffende maatregelen voor leerlingen met specifieke onderwijsbehoeften. Belgisch Staatsblad 28.08.2014 Ed. 2, 64624–64645 (28.08.2014)

Candipan, J.: Choosing schools in changing places: enrollment in gentrifying neighborhoods. Sociol. Educ. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040720910128

Cordes, S.A., Schwartz, A.E., Stiefel, L.: The effect of residential mobility on student performance: evidence from New York City. Am. Educ. Res. J. (2019). https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218822828

DeAngelis, C.A.: Does private schooling affect international test scores? Evidence from a natural experiment. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1614072

Demanet, J., Van Houtte, M.: Are flunkers social outcasts? A multilevel analysis of grade retention effects on same-grade friendships. Am. Educ. Res. J. (2016). https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216646867

D'Espallier, A.: Tot de Mde macht—een evaluatie van het M-decreet. [To the Mth power—an evaluation of the M decree.] Tijdschrift voor Onderwijsrecht en Onderwijsbeleid 2016-17/1-2, 26-34 (2016)

Dockx, J., De Fraine, B., Stevens, E.: De rol van de eerdere schoolloopbaan bij de overgang naar het secundair onderwijs. [The role of the earlier educational trajectory at the transition into secondary education.] Steunpunt Onderwijsonderzoek, research paper SONO/2017.OL1.1/1. http://www.steunpuntsono.be (2017). Accessed June 2023

DS: Begrijpend lezen en luisteren gaat achteruit in het basisonderwijs. [Reading and listening comprehension in decline in elementary education.] De Standaard, 4 April 2019. https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20190404_04301705 (2019). Accessed June 2023

Elacqua, G.M., Sanchez, F., Santos, H.A.: School reorganization reforms: the case of multi-site schools in Colombia. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1797830

EASNIE: Country policy review and analysis: Belgium (Flemish Community). European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. www.european-agency.org (2020a). Accessed December 2022

EASNIE: European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education: 2018 Dataset Cross-Country Report. European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. www.european-agency.org (2020b). Accessed December 2022

Eurostat: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (2022). Accessed June 2023

Eurydice: Grade retention during compulsory education in Europe: regulations and statistics. European Commission, Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency, Brussels, P9 Eurydice (2011). https://doi.org/10.2797/50570

Eurydice: National Education Systems: Belgium - Flemish Community. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/ (2022). Accessed December 2022

Ford, M.R.: School sector mobility in an urban school choice environment. Urban Educ. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919894033

Garrouste, M., Zaiem, M.: School supply constraints in track choices: a French study using high school openings. Econ. Educ. Rev. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102041

Gasper, J., DeLuca, S., Estacion, A.: Switching schools: revisiting the relationship between school mobility and high school dropout. Am. Educ. Res. J. (2012). https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831211415250

Goldstein, H., Burgess, S., McConnell, B.: Modelling the effect of pupil mobility on school differences in educational achievement. J. R. Stat. Soc. A (2007). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2007.00491.x

Goos, M., Van Damme, J., Onghena, P., Petry, K., de Bilde, J.: First-grade retention in the Flemish educational context: effects on children’s academic growth, psychosocial growth, and school career throughout primary education. J. Sch. Psychol. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.03.002

Haber, J.R.: Sorting schools: a computational analysis of charter school identities and stratification. Sociol. Educ. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040720953218

Hanushek, E.A., Kain, J.F., Rivkin, S.G.: Disruption versus Tiebout improvement: the costs and benefits of switching schools. J. Public Econ. (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(03)00063-X

Heck, R.H., Reid, T., Leckie, G.: Incorporating student mobility in studying academic growth in math: comparing several alternative multilevel formulations. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2022.2060265

Herskovic, L.: The effect of subway access on school choice. Econ. Educ. Rev. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102021

Hofflinger, A., Gelber, D., Tellez Cañas, S.: School choice and parents’ preferences for school attributes in Chile. Econ. Educ. Rev. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101946

Hofflinger, A., von Hippel, P.T.: Does achievement rise fastest with school choice, school resources, or family resources? Chile from 2002 to 2013. Sociol. Educ. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040719899358

Jabbar, H.: Competitive networks and school leaders’ perceptions: the formation of an education marketplace in post-Katrina New Orleans. Am. Educ. Res. J. (2015). https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831215604046

Jensen, S.S.: Effects of school-wide positive behavior support in Denmark: results from the Danish National Register data. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1840398

JOP: Zittenblijven en schoolse vertraging in het Vlaams onderwijs. Een kwantitatieve analyse 1996–1997. [Grade retention and delay in Flemish education. A quantitative analysis 1996–1997.] Jeugdonderzoeksplatform. Databank jeugdonderzoek. https://www.jeugdonderzoeksplatform.be/nl/databank-jeugdonderzoek/zittenblijven-en-schoolse-vertraging-in-het-vlaamse-onderwijs-een-kwantitatieve-analyse-1996-1997 (2023). Accessed June 2023

Juchtmans, G., Vandebroucke, A.: Overtuigingen als sleutel om zittenblijven te begrijpen en terug te dringen. Een kwalitatieve analyse van overtuigingen over zittenblijven in Vlaamse scholen. [Beliefs as the key to understand and reduce repeating. A qualitative analysis of beliefs about repeating in Flemish schools.] Pedagog Stud 90, 4–16 (2013)

Kosunen, S., Bernelius, V., Seppänen, P., Porkka, M.: School choice to lower secondary schools and mechanisms of segregation in urban Finland. Urban Educ. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916666933

Larsen, M.F.: Does closing schools close doors? The effect of high school closings on achievement and attainment. Econ. Educ. Rev. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.101980

Leist, S.A., Perry, L.B.: Quantifying segregation on a small scale: how and where locality determines student compositions and outcomes taking Hamburg, Germany, as an example. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1688845

Martin, M.O., von Davier, M., Mullis, I.V.S.: TIMSS 2019 Technical Report. TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/methods/pdf/TIMSS-2019-MP-Technical-Report.pdf (2020). Accessed December 2022

OECD: OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications. OECD Publishing (2018a). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en

OECD: PISA 2018 Technical Report. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/pisa2018technicalreport/ (2018b). Accessed December 2022

OECD: TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. OECD Publishing, Paris (2019). https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

OECD: PISA 2018 Results (Volume V): Effective Policies, Successful Schools. OECD Publishing (2020). https://doi.org/10.1787/ca768d40-en

OECD: Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing (2021). https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en

OVSG: OVSG Visietekst ‘Zittenblijven basisonderwijs’ (maart 2015). [Vision statement of the Educational Network of Cities and Municipalities concerning ‘Grade retention in elementary education’ (March 2015).] https://www.ovsg.be/onze-themas/leerlingenbegeleiding/onderwijsloopbaan/kansrijk-orienteren/zittenblijven-basisonderwijs (2015). Accessed June 2023

Pearman, F.A.: Gentrification, geography, and the declining enrollment of neighborhood schools. Urban Educ. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919884342

Pietsch, M., Tulowitzki, P., Hartig, J.: Examining the effect of principal turnover on teaching quality: a study on organizational change with repeated classroom observations. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1672759

Roda, A., Wells, A.S.: School choice policies and racial segregation: where white parents’ good intentions, anxiety, and privilege collide. Am. J. Educ. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1086/668753

Rumberger, R.W.: Student mobility: causes, consequences and solutions. National Education Policy Center. http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/student-mobility (2015). Accessed 16 June 2023.

Schmid, C., Trendtel, M., Bruneforth, M., Hartig, J.: Effectiveness of a governmental action to improve Austrian primary schools—results of multilevel analyses based on repeated cycles of educational standards assessments. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1620294

Shapira-Lishchinsky, O.: Ethical implications of TIMSS findings: an integrative model of student achievement. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1845750

Šťastný, V., Greger, D., Soukup, P.: Does the quality of school instruction relate to the use of additional tutoring in science? Comparative analysis of five post-socialist countries. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1770809

Stein, M.L., Burdick-Will, J., Grigg, J.: A choice too far: transit difficulty and early high school transfer. Educ. Res. (2021). https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20949504

STEP: Peiling Nederlands. Lezen, luisteren en schrijven in het basisonderwijs, 2018. [Assessment of attainment in Dutch. Reading comprehension, listening comprehension and writing in elementary education, 2018.] Steunpunt Toetsontwikkeling en Peilingen en Vlaams Ministerie van Onderwijs en Vorming. https://www.kwalificatiesencurriculum.be/overzicht-en-planning-peilingen-in-het-basisonderwijs (2019). Accessed June 2023

Taghizadeh, J.L.: Are students in receiving schools hurt by the closing of low-performing schools? Effects of school closures on receiving schools in Sweden 2000–2016. Econ. Educ. Rev. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102020

Tyack, D., Tobin, W.: The “grammar” of schooling: Why has it been so hard to change? Am. Educ. Res. J. (1994). https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312031003453

UNESCO-UIS/OECD/Eurostat: UOE data collection of formal education. Manual on concepts, definitions and qualifications. 15 June 2020. UNESCO-UIS, OECD, Eurostat. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/uoe-data-collection-manual-2020-en.pdf (2020). Accessed June 2023

Vanbuel, M., Van den Branden, K.: Promoting primary school pupils’ language achievement: investigating the impact of school-based language policies. Sch. Eff. Sch. improv. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1812675

Vandecandelaere, M., Schmitt, E., Vanlaar, G., De Fraine, B., Van Damme, J.: Effects of kindergarten retention for at-risk children’s psychosocial development. Educ. Psychol. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.950194

Van Landeghem, G., Van Damme, J.: A linear programming approach to the estimation of pupil flows from enrollment data. Steunpunt LOA, report 6. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/347047 (2002). Accessed June 2023

Van Landeghem, G., Van Damme, J.: Geboortecohorten doorheen het Vlaams onderwijs: Evolutie van 1989–1990 tot 2001–2002. [Transition of birth cohorts through Flemish education: evolution from 1989–1990 to 2001–2002.] Steunpunt LOA, report 16. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/1937832?limo=0 (2004). Accessed June 2023

Van Landeghem, G., Dockx, J., Aesaert, K., Van Damme, J., De Fraine, B.: PIRLS, de peilingen begrijpend lezen en loopbanen doorheen het lager onderwijs. De impact van alternatieve trajecten op de interpretatie van de prestatiemetingen. [PIRLS, the national assessment of attainment goals in reading comprehension and trajectories through primary education. The impact of alternative trajectories on the interpretation of the test results.] KU Leuven, Centre for Educational Effectiveness and -Evaluation. https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/progress-in-international-reading-literacy-study-pirls#Resultaten_PIRLS_Repeat (2019). Accessed June 2023

Van Landeghem, G.: De peilingen in het Vlaams basisonderwijs: een alternatieve interpretatie van de resultaten. [Assessment of attainment goals in Flemish primary education: an alternative interpretation of the results.] Tijdschrift voor Onderwijsrecht en Onderwijsbeleid 2020-21/3, 226–240 (2021)

Van Landeghem, G.: An indicator of early school leaving per school: every pupil counts. Qual. Quant. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01302-8

VMOV: Statistisch jaarboek van het Vlaams onderwijs 2020–2021. [Statistical annual of Flemish education 2020–2021.] Vlaams Ministerie van Onderwijs en Vorming. https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/onderwijsstatistieken/statistisch-jaarboek-van-het-vlaams-onderwijs (2022a). Accessed June 2023

VMOV: Databundel school. [School data set.] Vlaams Ministerie van Onderwijs en Vorming. https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/directies-en-administraties/mijn-onderwijs/wat-vind-ik-op-mijn-onderwijs/databundel-school (2022b). Accessed June 2023

Voight, A., Giraldo-García, R., Shinn, M.: The effects of residential mobility on the education outcomes of urban middle school students and the moderating potential of civic engagement. Urban Educ. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085917721956

VR: Regeerakkoord 2019–2024. [Flemish Government 2019–2024 coalition agreement.] https://www.vlaanderen.be/publicaties/regeerakkoord-van-de-vlaamse-regering-2019-2024 (2019). Accessed June 2023

Welsh, R.O.: School hopscotch: a comprehensive review of K-12 student mobility in the United States. Rev. Educ. Res. (2017). https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316672068

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Strategic Policy Support division of the Department Education and Training (Flemish government) for the extraction of the data set from the administrative databases and for authorising and enabling its delivery in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (European Union).

Funding

Part of the writing process was supported by KU Leuven Internal Funds grant ZKE0398—C24M/21/013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Clustering algorithm

Appendix: Clustering algorithm

The 1999 birth cohort refers to 69,361 pupils and 3272 administrative schools.

-

Step 1:

pupils with common trajectories

-

The set of 69,361 pupils is partitioned according to the array sy, y = 2004–2005, 2005–2006, …, 2013–2014, called the “trajectory”.

-

The element sy is empty if the pupil is not enrolled in Flemish primary education in school year y;

-

Otherwise, the element sy contains the identifier of the administrative school in which the pupil is enrolled in year y.

-

This partition consists of 26,145 elements, called “pupil trajectory clusters”.

-

-

Step 2:

links

-

Among the 26,145 pupil trajectory clusters, 2858 contain 4 pupils or more. These pupil trajectory clusters are called “links”.

-

-

Step 3:

real schools

-

Among the 3272 administrative schools, 2762 appear in the trajectory of at least one link.

-

This subset of 2762 administrative schools is partitioned according to this rule:

no link crosses the boundary between two elements of the partition (i.e.: for any given link, the schools involved in its trajectory are included in a single element of the partition)

and

no element of the partition can be broken up further without creating such a link.

-

This partition consists of 2324 elements, called “real schools”.

-

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Landeghem, G. Counting pupils moving between elusive schools: between-school pupil mobility in the Flemish primary education market. Qual Quant (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01861-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01861-6