Abstract

For the past 80 years survey researchers have used a probability sampling framework. Probability samples have a well-defined set of quality criteria that have been organized around the concept of Total Survey Error (TSE). Non-probability samples do not fit within this framework very well and some possible alternatives to TSE are explored. In recent years, electoral polls have undergone changes as a result of the dispersion of public opinion due mostly, but not only, to the development of the web and social media. From a methodological point of view, the main changes concerned sampling and data collection techniques. The aim of the article is to provide a critical contribution to the methodological debate on electoral polls with particular attention to the samples used which appear to be more similar to non-probability samples than to the traditional probability samples used for many decades in electoral polls. We will explore several new approaches that attempt to make inference possible even when a survey sample does not match the classic probability sample. We will also discuss a set of post hoc adjustments that have been suggested as ways to reduce the bias in estimates from non-probability samples; these adjustments use auxiliary data in an effort to deal with selection and other biases. Propensity score adjustment is the most well know of these techniques. The empirical section of the article analyzes a database of 1793 electoral polls conducted in Italy from January 2017 to July 2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The last two decades of the XX century may represent the golden age of electoral polls. People were easily reachable through domestic telephone lines using the CATI system (computer-assisted telephone interviewing) and were generally inclined to answer the questionnaires; response rates frequently exceeded 70% (Sakshaug et al. 2019). In Italy, for example, more than 90% of households had a home telephone subscription and this made it relatively easy to reach a representative sample of voters with relatively low rejection and non-response rates. Over time, the percentage of families subscribing to the domestic telephone has progressively decreased and at the same time the percentage of people refusing to answer has grown significantly.

To include those segments of the population that no longer use the home telephone, it was necessary to first introduce interviews on mobile phones and then interviews via the web. The current situation usually envisages the composition of a sample that includes a share or CATI interviews, which remains the most widespread method for some social categories, with a share of CAMI (computer-assisted mobile interviewing) and/or CAWI (computer-assisted web interviewing).

The adoption of mixed survey techniques produces new methodological problems concerning: (a) the need to adapt the questionnaire to the different survey methods; (b) having to establish the proportion of interviews to be carried out with the different data collection techniques; (c) the data coming from different sources that refer to different populations (subscribers to domestic landline telephony, owners of a mobile phone and owners of an internet subscription) must then be merged into a single data matrix with different probabilities of being reached by the different detection techniques; (d) finally, it is necessary to decide how to homogenize the data coming from these different sources with ex-post weighting procedures.

In addition to the methodological aspects which we will deal with in the next paragraphs, the impact of the changes that have taken place in the socio-political context should be evaluated and in particular the diffusion of the internet and social networks which have favoured the rise of populisms of all kinds and the polarization exacerbated by social networks of electoral competitions in many western democracies. All this has impact on political polls in various respects: due to the greater difficulty in reaching a representative sample of voters; due to the expansion of refusals by many individuals to grant the interview; due to the increased fragmentation of the interviewees into more and more unstable parties/movements with difficult connotations that have taken the place of parties and alignments with a consolidated tradition and political culture; lastly, due to the growing number of interviewees who declare they want to abstain or are undecided in answering the question about their voting intention.

All of these factors reached their peak in 2016 when events such the US presidential elections and the Brexit referendum in Great Britain as well as others elections in various European countries (Italy, Greece, Netherlands, France, Germany, etc.) have manifested the crisis of electoral polls even in countries where they seemed to work for decades.Footnote 1 Therefore, taking into account the transformations of recent years in the field of electoral polls, and more generally in the web-survey, the objective of our analysis is to describe the characteristics of the sampling techniques adopted today and their nature with respect to the classic distinction between probability and non-probability techniques.

2 Literature review

There is a broad literature on surveys. Obviously, it is impossible to present it exhaustively here, even if we wanted to limit it to the most recent years. We have therefore chosen to present a review of the emerging thematic issues, pointing out the contributions that we believe are the most significant. First, let’s examine the contributions that have focused on the changes introduced in survey research, including electoral polls, due to the diffusion of the web and the social media. These contributions highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the web-survey such as the containment of time and costs, the low response rates, the possible incentives to be used to recruit subjects to answer the questionnaires, the phenomenon of interruptions—i.e. subjects who start to fill in the questionnaire but do not complete or send it—, etc. (Alvarez and VanBeselaere 2005; Bethlehem and Biffignandi 2012; Couper 2000; Couper et al. 2007; Fricker and Schonlau 2002; Gittleman and Trimarchi 2010; Lee 2006a; Miller 2017; Olson 2006).

A feature of surveys in the age of the internet and social media is the progressive affirmation of the online panels (often referred to as the opt-in panel to mean an online panel not recruited via probability sampling). They are made up of profiled subjects who are recruited following an occasional participation in a telephone research, for example with the CATI or CAMI technique, or from users of certain websites, or online consumers of certain services. Once an individual agrees to be recruited to an online panel, usually in exchange for some form of remuneration, they are anonymously profiled on the basis of a number of socio-demographic characteristics. This profiling makes it possible to send survey invitations to people who are eligible to participate in them, preemptively reducing the number of false registrants. One of the problems of online panel surveys is represented by the presence of so-called heavy internet users, present with multiple identities in the panel in order to collect more incentives. It is estimated that the share of these fictitious identities amounts to about 50% of participants in an online panel. This leads to a number of problems related to errors due to responses not matching the profiles they are supposed to come from (Bach and Eckman 2018; Callegaro and DeSogra 2008).

On the internet there are platforms that provide, upon request of institutions, lists of names willing to participate in a survey: Dynata (www.assirm.it/aziende_associate/dynata/), Bilendi (www.bilendi.it), Norstat (www.norstatpanel.com), Toluna (it.toluna.com/).Footnote 2 So there are providers who, upon request, provide samples which they say are representative for any market research, opinion poll or other kind of surveys.

As can be easily understood, the adoption of an online panel involves some other problems: among these, one of the most important is the so-called motivated misreporting, i.e. the mechanism by which respondents to a survey provide incorrect answers or answers that do not correspond to their opinions with the only aim of reducing the length of the questionnaire and therefore the burden in terms of time and energy necessary for its compilation (Bach and Eckman 2018). The comparison between research conducted with traditional interview techniques (face-to-face, CATI and CAMI) and the new web-based survey techniques (CAWI and/or online panel), has been the subject of numerous studies both by professional associations such as the American Association for Public Opinion Research and Esomar (AAPOR 2011; 2013; Icc/Esomar 2016), and by independent researchers and scholars (Chang and Krosnick 2009). The results presented are generally unfavorable to surveys using web samples, even if, there is confidence that in the coming years, due to the exponential increase in web users, better results should be obtained (Duffy et al. 2005).

Currently, the prevailing approach relies on the mixed survey techniques which integrate a quota of CATI interviews, a CAMI quota and a quota of CAWI interviews. In general this solution is believed to solve the problems of non-coverage and non-response of web-surveys.

A brief mention should be made of the new web and social media research techniques which are independent of web-survey (Asur and Huberman 2010; Erikson and Wlezien 2008).

The most important and controversial issue concerns the so-called new sampling techniques that are compatible with the web-survey. The methodological literature on this topic is truly impressive (see among others: Berzofsky et al. 2009; Biernacki and Waldorf 1981; Brick 2011; Brick and Williams 2013; Copas and Li 1997; deRada Vidal 2010; Deville and Särndal 1992; Di Franco 2010; Duffield 2004; Dutwin and Buskirk 2017; Elliott and Haviland 2007; Elliott 2009; Handcock and Gile 2011; Kalton and Flores-Cervantes 2003; Kott 2006; Lee 2006b; Lee and Valliant 2009; Mercer et al. 2017; Revilla 2015; Schonlau et al. 2009; Smith 1983; Sudman 1966; Valliant and Dever 2011; Wejnert et al. 2007; Yeager et al. 2011).

In summary, the proposals consist in adopting mixed sampling techniques, both probability and non-probability, or in seeking the conditions to make it possible to infer results from the sample to the entire target population even when non-probability samples are adopted. The feeling is that this comeback of non-probability samples is due to the need to admit that web-surveys are ultimately conducted on samples of self-selected subjects.Footnote 3 Strictly speaking, therefore, these samples should be defined as convenience and not non-probability or judgmental samples. It is not necessary to be an expert in inferential statistics to know that when there is a self-selection of the interviewees it is not possible to infer the results to the target population, and the results themselves of these samples will be systematically biased. Selection bias consists of systematic differences between the sample values and the unknow parameters of the population, due to problems concerning the composition of the sample and not related to other types of errors. Usually the bias derives from problems of coverage and non-response. The samples of the surveys conducted on the web do not originate from a sampling frame that entirely covers the target population, but in the best case a random extraction takes places from a list of subjects who have been recruited on the web to form the online panels. Methodological research has focused in identifying the conditions under which inferences can be made when using this type of sample. It can be seen that in web-surveys the sampling frames do not adequately cover the target population and a significant share of the sampled subjects do not respond to the questionnaire (participation bias). For these problems, the proposed solution consists in carrying out statistical adjustments, more or less sophisticated, to correct the imbalances of the sample (ex-post weightings, use of complex statistical models, etc.; see, among others, Atkeson et al. 2014; Bethlehem 2010; Bethlehem et al. 2011; Biemer 2010; Biemer and Peytchev 2012; Blumberg and Luke 2007; Bosio 1996; Busse and Fuchs 2012; Callegaro and Poggio 2004; Dever et al. 2008; Dillman et al. 2009; Groves 1989; 2006; Groves and Lyberg 2010; Groves et al. 2004; Link and Lai 2011). It should be noted that with non-probability samples it is necessary to use statistical models in all phases of the survey process from sample selection to the estimation of results, but this does not exclude the possibility that these sample corrections are unsatisfactory. The primary alternative to non-probability based online panels is river sampling where potential respondents are recruited through similar sources but are targeted for only one survey.

Unlike online panels, with the river sample (DiSogra 2008) the profile of the respondents is not known in advance, but must be reconstructed afterwards. In any case, both online panels and river sampling present the serious problem of systematically excluding all people who do not use the internet. Obtaining a broad range of potential respondents is critical to the success of any sampling process, and respondents recruited through different websites have been found to exhibit extremely diverse demographic (and other characteristics) distributions. Recruiting from a set of diverse sources improves the likelihood of meeting the requirement for maximum sample heterogeneity; however, it also increases survey time and cost. Although web-survey are conducted on non-probability samples, it is not possible to find clear indications to identify the recruitment procedures actually applied (see par. 4). Non-probability surveys generally rely on selection of subjects to obtain the desired sample composition while data collection is in progress. Usually this is achieved through quotas, in which the researcher constructs a particular distribution across one or more variables. Quotas are defined by a cross-classification of socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, age group, etc. Each quota requires a defined number of interviews to be performed. The end result is a sample that matches the stratification identified in the sampling design. The use of quotas is based on the assumption that the individuals included in each quota are interchangeable with the unsampled individuals, i.e. that they share the same characteristics. If this hypothesis is satisfied, the sample will have the correct composition on the control variables, allowing the estimation of means and/or proportions that can be generalized to the target population. However, there is a growing consensus that basic demographic variables such as age, gender, education, occupational status, geographic residence, are insufficient to achieve interchangeability of subjects. Some more complex sampling strategies allow researchers to control for several other dimensions, i.e. additional stratification variables. Various procedures have been proposed in the literature such as the use of Euclidean distances,Footnote 4 propensity score matchingFootnote 5 and routing.Footnote 6

We conclude this review by stating that the debate and controversies surrounding the adoption of non-probability samples certainly cannot be considered closed. For some these samples are not adequate for surveys research; for others, however, they are feasible if used with the due methodological control procedures. In this regard, the following words of Kish may be useful:

Great advances of the most successful sciences – astronomy, physics, chemistry – were and are, achieved without probability sampling. Statistical inference in these researches is based on subjective judgment about the presence of adequate, automatic, and natural randomization in the population [...] No clear rule exists for deciding exactly when probability sampling is necessary, and what price should be paid for it [...] Probability sampling for randomization is not a dogma, but a strategy, especially for large numbers (Kish 1965, 28-29).

In the next paragraphs we will analyze a large database of electoral polls carried out in Italy from 2017 to 2023 and we will try to illustrate, on the basis of the information available to us, the sampling techniques adopted.

3 Methodology

We now describe the methodology used, while in the next paragraph we will present the results of the analysis. The data are taken from a database containing some information on the electoral polls published in Italy by the mass media from 1 January 2017 to 31 July 2023. The information relating to the electoral polls was downloaded from the institutional website of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers: www.sondaggipoliticoelettorali.it.

We collected 1793 polls focusing on voting intentions for the next political elections. As mentioned, the results of these polls have been disseminated by the mass media and are governed by rules that require the drafting of an information note that presents methodological information useful for assessing the correctness of the polls carried out by various agenciesFootnote 7 (Di Franco 2018; 2021). From our analysis it emerged that in many documents there are important gaps with respect to what is required by current legislation, especially in relation to purely methodological information.

We focusing our attention on the elements that concern very important aspects for the evaluation of the results of the poll such as the sample size, the sampling error, the confidence interval, the number and percentage of non-contacts, non-respondents and replacements made, the full text of all the questions and the percentage of interviewees who answering each of them.

Following the descriptive analysis, we found a second serious gap in the methodological notes concerning information on the number of contacts and rejections: 319 out of 1793 polls published (equal to 17.8%) do not report this information. To take this important information into account, we have designed a new variable computing the ratio between the number of people contacted and the number of interviews carried out. Thanks to this variable, we can evaluate for each poll how many subjects it was necessary to contact to carry out a valid interview. The mean value of the ratio is equal to 4.93 (the standard deviation is 3.22) which indicates that to carry out a valid interview it was necessary to contact about five subjects. In other words: on average, for each interview carried out more than four refusals were registered.

By analyzing the mean values of the ratio by the interview techniques we can see in which cases the most critical issues are recorded.

Let’s first analyze the polls conducted using a single collection technique. When the interviews are carried out using an online panel of respondents the average of ratio is equal to 1.26 (the standard deviation is 0.15); the polls carried out with CATI present an average of ratio equal to 5.24 (the standard deviation is 1.28); almost all surveys carried out with the CAWI technique do not provide this information. It seems clear that the problem particularly concerns the use of the CAWI and this suggests that in fact the institutes that use this technique do not carry out a probability sampling but draw on a form of judgemental selection if not a self-selection of the subjects who frequent the web.

When the polls are carried out using mixed techniques of data collection the average result of the contacts/interviews ratio are: 7.60 (the standard deviation is 4.07) with CATI-CAWI; 4.93 with CATI-CAMI (the standard deviation is 2.96); 5.25 (the standard deviation is 2.20) with CATI-CAMI-CAWI.

We have computed the coefficient eta to quantify the strength of the association between the contacts/interviews ratio and the technique of data collection. The value obtained (0.627) allows us to establish the existence of a significant association between the two variables examined.

By examining the differences between the mean values, it is possible to find a significant effect of the data collection technique on the ratio between the number of contacts and the number of interviews carried out. Undoubtedly, the polls that resort to web and mobile interviews have significantly higher associations than those conducted only with CATI and those that resort to the combination of CATI and CAWI. Polls conducted on an online panel are an exception because, being the sample made up of subjects who accept to be interviewed repeatedly over time, they have very low values.

In Table 1 we show the descriptive statistics relating to the following variables: duration of the survey in number of days (label n_days), sample size (nsample), sample error (error), number of subjects contacted (n. contacts), number of subjects who refused the interview (n. waste), value recorded on contacts/interviews ratio (ratio), percentage of respondents who declared their intention not to vote or who declared themselves undecided (no-vot).

On average, the polls analyzed were carried out in just over two days (2.7 days; 1.978 the standard deviation; 1 the minimum value; 31 the maximum value).

The sample sizes vary in a range from 500 to 16,000 cases; the average is 1374.14, the standard deviation is 890.994.

Linked to the size of the sample, the level of sample error in the analyzed polls varies between 0.9 and 4.4 percent. The average error is three percent, the standard deviation is 0.499.

Finally, with regard to the request to provide information on the number and percentage of subjects who do not answer the poll questions, in our analysis—since we have considered only the question relating to voting intentions, whose formulation is: “if you voted today [or, if you had voted yesterday] for the Chamber of Deputies, which party would you vote for [or, would you have voted for]?”—we have taken into consideration the presence of the percentages of the undecideds and those who intend to abstain from voting.

In 20.52% (368 cases) of polls, neither the percentage of undecideds nor that of abstainers was reported.

In the next paragraph we will try to evaluate the impact of the new problems characteristic of online surveys, such as the possible difference in the results attributable to the type of data collection technique or techniques and the type of sample used. We will submit to empirical control the influence of survey and sampling techniques on the variation of the results in terms of the estimates produced. In particular we will examine the possible influence of variables such as: sample size, sampling error and sample type, whether probability or non-probability.

4 Results and discussion

Table 2 shows the distribution of the 1793 polls by interviewing technique and by year. We need to clarify the strong connection between the data collection technique and the type of sample adopted. In subsequent analyses, we will sometimes refer to sampling technique and other times to the interviewing tecnnique depending on the aspect of the analysis that we want to highlight.

The mixed CATI-CAMI-CAWI system went from 12.7% in 2017 to 41.1% in 2022 (40.8% in the first seven months of 2023), becoming the most widespread method of data collection. Conversely, the surveys carried out only with CATI interviews or with the CATI-CAMI, which still made up more than a third in 2017 (39.6%) from 2020 to today have practically disappeared. However, the CATI remains a method still very present in association with the CAMI and/or CAWI.

When the surveys are carried out using mixed survey techniques, institutes almost never indicate the proportion of interviews completed with each technique, and this does not allow us to quantify the weight of the telephone interviews on the total number of interviews carried out.

The CATI-CAWI mixed technique follows an oscillating trend, going from 13.7% in 2017 to 19% in 2023 (see Table 2). In general, in recent years, 68.7% of electoral polls have adopted some mixed method and, among these, the CATI-CAMI-CAWI is consolidating. In the remaining 31.3%, polls are carried out only via the web (CAWI or online panel).

In our opinion, the variety of combinations between the different techniques adopted by the polling agencies is an indicator of how much the problem of coverage of the Italian voter population is still looking for a satisfactory solution. As mentioned, it is necessary to specify the direct connection between the techniques of data collection and the methods of selection (sampling) of the interviewees. Usually for the CATI the selection was conducted on the list of landline telephone subscribers and therefore the target population consisted of all the subscribers who were included in the telephone directories. In recent years, due to the substantial decrease in home telephony subscription, the RDD (random digit dialing) technique has been used. For the CAMI, as there are no lists of subscribers to mobile telephony services, the selection usually takes place by randomly dialing numbers and, once the consent of the respondent has been obtained, checking whether they match the characteristics defined by the sampling plan, the procedure therefore falls within the so-called quota sampling (Berinsky 2006; Kish 1965; 1987). Finally, for the CAWI interviews, with or without an online panel, it is strictly not possible to define a target population, not even in very general terms such as, for example, internet users, since, as mentioned, this is a group of subjects who in fact choose whether or not to participate in a survey. In this case we fall within that type of sampling which is defined as convenience or opportunity.

It is no coincidence that the first glaring anomaly that we found in the analysis of the information documents published on the institutional website concerns the definition of the type of sample adopted. According to the regulations in force (see art. 2 of the new regulation approved with resolution n. 256/10/CSP, published in the Official Gazette no. 301 of 27.10.2010) the following is requested:

“a clear distinction between surveys (based on scientific data collection methods applied to a sample) and other polls with no scientific value such as expressions of opinion (based on the spontaneous participation of users) and which therefore cannot be published or disseminated under the name of survey”.

From this it can be deduced that all polls should be conducted with probability sampling techniques or at least with techniques that make it possible to reach a representative sample of the population of Italian voters.

A little further on, the regulation lists the information to be included in the document attached to the survey published on the institutional website. In point 11, in contradiction with what is stated in the art. 2, it is asked to indicate whether it is:

“probability or non-probability sampling, survey based on panel and possible weighting”.

In short, it would seem that contrary to what we have in the art. 2, any type of sample is fine as long as it is explicit. Continuing in reading, in point 12 the “representativeness of the sample including indication of the margin of error” is required. In this case, we wonder how it is possible to compute the sampling error if the sample is non-probability. In point 13 it is asked to indicate “the method of gathering information” and in point 14 the “numerical consistency of the sample of interviewees, the number and percentage of non-contacts, non-responders and substitutions made”.

Actually, with few exceptions, agencies never openly state that their sample is non-probability, but usually fail to specify this important information. We provide below the feedback of the information available: in 1431 polls (79.8%) they declare that they have produced a probability sample, i.e. with a random selection of the interviewees; in 362 cases (20.2%) the selection procedure is not provided or is defined as non-probability.

It should be repeated once again that the sampling error is a parameter that can only be determined if we have a probability sample: in all 1793 polls analyzed, it is referred to as such, but the accounts do not add up when examining the type of sampling adopted. As mentioned, only in 1431 (79.8%) cases the sample is claimed to be probability (or random); in the remaining 362 cases (20.8%) the sample is described as representative of some characteristics of the population although the selection was non-probability. In this regard we must specify that one thing is the technique of selecting cases from a population (and here probability samples distinguish themselves from non-probability or judgmental sample; see Di Franco 2010), another thing is the outcome of the sampling which considers the isomorphism, i.e. the representativeness between the sample reached and the population from which it was drawn. Very often the two levels are confused, but this should not be done (Kruskal and Mosteller 1979a; b; c; 1980; Marradi 1989; 1997). Most likely, the polling organizations consider their samples probability or random by adopting the new hybrid sampling techniques proposed in recent years, which we referred to in par. 2. In any case it is not possible to obtain any information in this regard in the documents we have analyzed.

Considering the criteria on the basis of which the representativeness of the sample was defined, we find greater homogeneity. In 100% of cases the samples are declared representative of the population with respect to gender and age group. In 96% of the polls analyzed, representativeness by geographical macro-area is added to the first two criteria; in 63.6% also the representativeness with respect to the demographic dimension of the municipality of residence of the interviewees. The representativeness with respect to the education level of the interviewees is indicated in 39.8% of the cases; only in 14.6% of cases the representativeness concerning the working conditions of the interviewees is taken into account. On the basis of these results, and considering what we said in par. 2, the overall stated level of representativeness is unsatisfactory. For years, the literature has highlighted how socio-demographic variables are no longer sufficient to study voters’ voting choices (Itanes 2018).

It is interesting to examine how the representativeness of the samples varies with the different technique of data collection. As we have seen in Table 2, the most frequent method is the CATI-CAMI-CAWI: assuming that the total number of polls carried out with this technique is equal to 100, 45.7% present a representativeness based on four characters; 33% on five; 19.2% on three; 1.5% on two and 0.5% on six. The CATI-CAWI presents 83.4% of the polls with a representativeness of the samples in terms of four characters. For the polls that adopt only the CAWI, present 44.2% a representativeness consisting of four characters; 31.8% of five; 11.7% of three; 10% of six. 91.8% of polls conducted only with CATI techniques present a representativeness of the samples consisting of four characters. 52% of polls conducted with the mixed CATI-CAMI technique present a representativeness of the sample by five characters; 29% a representation made up of three characters.

Before providing the results of an electoral poll, it is necessary to weight the sample, taking into account both the socio-demographic criteria used in the sample design and the results of the elections closest to the date the poll was created. In 34.4% of the cases (616) no type of weighting is declared; in 30.8% (552) of the cases polling institutes declared that they carried out the weighting only with respect to socio-demographic characteristics and in 34.8% (625) both weightings. These results are not credible and we believe that all agencies adopt weighting techniques which they evidently prefer to keep confidential.

In 17.8% (319 cases) of the polls, neither the number of people contacted nor the number of non-respondents (whether because they refused or for any other reasonFootnote 8) is indicated. Among the agencies that provide this information (82.2%), the number of contacts varies between a minimum of 1000 and a maximum of 28,391 individuals. The average number of contacts is 5039.32; the standard deviation is 2777.00. The number of refusals varies between a minimum of 41 and a maximum of 24,389; the average is 3870.42; the standard deviation is 2765.44.

Under current Italian legislation, when the survey is conducted with mixed techniques, the agencies should indicate the proportion of interviews conducted with the different techniques. Out of 1165 surveys that eligible for this purpose, the information is almost never provided.

Moreover, when carrying out an electoral poll it is—or rather it would be—necessary to indicate among the results the percentage of interviewees who declared themselves undecided and that of those who express their intention to abstain. The majority of the polls we analyzed lack these information: only 12.9% of the polls (232 cases) report the percentage of undecideds and only 67.7% (1213 cases) the percentage of those intending to abstain which often includes, but we do not know to what extent, even the percentage of undecideds.

Table 3 presents the average percentages of undecideds and abstentions by type of interview technique, obviously considering only the surveys that provide information in this regard (1195).

Examining the different averages, it is clear that when the polls are carried out with CAWI, they show an absolutely improbable percentage of undecided people and abstentions (30.69%), if compared with only the percentage of abstentions recorded in the 2022 general elections (36.2%). In general, the interview techniques have a significant impact on the estimate of the percentage of undecideds and abstainers.

With regard to the number and/or percentage of non-contacts, non-respondents and substitutions and the percentage of people who declared themselves undecided or willing to abstain as mentioned, we instead found numerous gaps. We have highlighted how these problems concern in particular the polls carried out with the CAWI and this leads us to assume that in fact the agencies that use it do not carry out a probability sampling but select the interviewees with invitations addressed to network of users who have registered on a website or on online panel (see par. 2).

To quantify the impact of the different techniques on the interviewee selection, we computed the ratio between the number of contacts, when this information was declared (1474 out of 1793), and the number of interviews carried out. The average is 4.93 contacts for each interview performed (minimum 1.02; maximum 18.58) which means that on average to carry out an interview it was necessary to contact five subjects, obtaining four negative results. We can now evaluate how the contacts/interviews ratio varies with respect to the survey technique. Examining the data in Table 4, it is possible to notice a significant impact of the survey technique on the contacts/interviews ratio. The CATI-CAWI combination is that with the least favorable ratio: almost eight contacts were required on average for each interview carried out.

On the contrary, the surveys conducted with the CAWI and/or online panels, being the sample made up of subjects who agree to be interviewed repeatedly over time, in exchange for some reward, have average values of the ratio slightly higher than one. Although, on the one hand, online panels offer an excellent performance in the contacts/interviews ratio, on the other they present at least two problems: the first concerns subjects remaining in the panel for a long time. In this case there is the risk of an effect that we could define as “professionalization of the interviewee”. In short, a subject who is repeatedly interviewed tends to increase his sensitivity and information on the topics on which he will have to respond and in this way he acquires skills that he would not have otherwise, thus becoming a professional and no longer a mere interviewee; the second problem is the phenomenon of heavy internet users described in paragraph 2.

We conclude by trying to answer the most important question of our analysis: how much does the survey/sampling technique affect the results obtained from a survey?

To quantify the influence of the poll technique, we set up a multiple linear regression model defining the percentage of abstainers and uncertain voters as dependent variable and the following five as independent and control variables: sampling error; contacts/interviews ratio, days needed for the completion of the poll, and two Boolean variables (with values 0 = absence and 1 = presence) which indicate the presence of the CAWI and CATI-CAWI poll techniques. We operationalized the two Boolean variables because we are interested in evaluating the effect of web-based survey techniques, either exclusively (CAWI) or in association with the CATI technique. The analysis was conducted on all the polls that reported the estimates of the undecideds and abstainers (1156 cases).

The model reproduces 32.5% of the variance of the dependent variable (R = 0.573; R squared = 0.329; adjusted R squared = 0.325). This portion of the reproduced variance turns out to be statistically significant (F = 93.684; sig. 0.000), the statistics of the model residuals (mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1) confirm the goodness of fit of the regression model.

Table 5 shows the unstandardized (b) and standardized (beta) coefficients of the independent variables of the regression model with respective values of statistical significance.

The analysis of the beta weights confirms that the contribution of the five independent variables is significant in explaining the variance of the dependent one. Of the five independent variables, CATI-CAWI (0.311) and n_day (0.066) have a positive beta weight; sample error (− 0.361), contacts/interviews ratio (− 0.180) and CAWI (− 0.096) have a negative beta weight.

In other words, the percentage of non-voters (dependent variable) is directly proportional to the CATI-CAWI and to the duration in days of the poll, while is inversely proportional to the sample error, the contacts/interviews ratio and CAWI.

In detail, the CATI-CAWI technique (beta = 0.311) increases the estimate of the percentage of abstainers and undecideds with a triple weight compared to the CAWI technique, which tends to underestimate the values of the dependent variable. To further investigate the effect of the collection/sampling technique on the results of electoral polls, we conducted a one-way analysis of variance considering as dependent variables the percentage of undecideds and abstainers, the sum of center-right parties, the sum of center-left parties and the percentage of the Five Star Movement. The independent variable is the collection/sampling technique divided in four categories: CATI-CAMI-CAWI, CAWI (panel), CATI-CAWI, CATI and CATI-CAMI.

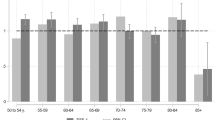

For reasons of space, after checking the statistical significance of the results obtained and after conducting post-hoc tests with the HSD technique of Tukey, Scheffe and Bonferroni, we present in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 the graph of the averages of the four analyzes carried out.

Figure 1 shows the average percentage of undecideds and abstainers by collection/sampling techniques. The highest average value is 42.30% obtained from the polls carried out with CATI-CAWI, followed by the CATI and CATI-CAMI polls with 40.65%. The CATI-CAMI-CAWI polls rank at 38.91% and those conducted with only the CAWI, with or without an online panel, have an average value of 30.69% which is decidedly lower than all the other techniques.

Compared to the sum of the votes of the center-right parties, the average results of the CATI-CAMI-CAWI (46.19%), of the CAWI (44.81%) and of the CATI-CAWI (45.39%) are different but not in a striking way.

The polls conducted only through telephone interviews, with the CATI or with the CATI-CAMI, present a significantly lower average value (40.35%) and this highlights a difference between samples composed only of interviewees reachable by telephone compared to the samples that are also conducted through interviews via the web.

Moving on to consider the results of the sum of the center-left parties (see Fig. 3), the differences between the various types of poll are not particularly pronounced, going from 46.16% (CATI-CAMI-CAWI), to 44.81% of the CAWI (panel), 45.39% of CATI-CAWI and 40.35% of CATI and CATI-CAMI.

Also in this case, the polls conducted only through telephone interviews present the most different results compared to all the other techniques considered.

Figure 4 shows the averages of the percentage of votes attributed to the Five Star Movement by type of poll. Also in this case the averages of the polls conducted with the CATI-CAMI-CAWI (18.35%), with the CAWI (18.48%) and with the CATI-CAWI (19.31%) are quite similar. The most distant value (24.98%) again is that of the CATI-CAMI polls.

5 Discussion and conclusions

From our regression and anova analysis emerged that the polls conducted with only telephone interviews present very different results from those which include, albeit in different proportions and unknown to us, also the interviews on the web. This is an indicator of structural differences within the various samples which are not compensated by the weighting operations implemented by the various polling agencies. We must also emphasize that due to the lack of information, which should also be provided according to current legislation, our analysis was limited to the information available. Transparency is essential. Whenever non-probability sampling methods are used, there is a higher burden than that carried by probability samples to describe the methods used to draw the sample, collect the data, and make inferences. Too many online polls consistently fail to include information that is adequate to assess their methodology.

As mentioned, a fundamental aspect concerns the evaluation of the effects due to the growing use of samples increasingly formed on the web. As long as the survey technique was the CATI, it was possible to argue that the results of the surveys could be generalized to the target population, landline telephone subscribers, within the margins of the sample error.

In recent decades, all agencies have had to adapt to the changes in technology and lifestyle of voters and therefore all the innovations we have discussed in our contribution have intervened. The assessment of these changes, at least with regard to Italy and in relation to the last few years we have taken into consideration, shows a negative balance compared to the previous situation, above all due to the recruitment procedures that are in vogue on the web, so much so that with regard to the selection of the interviewees, some agencies have adopted—moreover without declaring it clearly and transparently in their information documents—a radical choice which consists in abandoning classical probability sampling. By now, several agencies conduct their surveys by recruiting panels made up of volunteers who participate in one or more surveys in order to receive some kind of incentive.

It should be emphasized the great difference between a survey conducted on a probability sample and a survey conducted on a web-sample or online panel. In the first case the inference of the results to the target population is supported by the theory of probability and by the theorems of statistical inference; in the second case the inference is based on inductive models that they not have a comparable theoretical foundation (see par. 2 in this regard). Supporters of online panels claim that their inductive models work quite well and in some cases even better than probability sample, especially when rejection rates are recorded so high that these samples are actually the result of self-selection by respondents.

In any case, the future of opinion polls will depend on their adaptation to the new communication technologies which are and will increasingly be attributable to the level of the single individual. In the previous era, when the CATI technique dominated, the means of communication used was the domestic telephone user which referred to the family nucleus: therefore the interviewed subjects were selected within the family nucleus. The diffusion of the means of communication on a personal level is substantially modifying the bond between individuals and families. The debate is ongoing on this issue and well and the consequences in terms of representativeness of the samples reached are not clear.

We close out contribution by indicating some lines of research that could be useful in the future to improve the sampling techniques used in surveys. Starting from the observation that non-probability samples are back in vogue, it is necessary to investigate the theme of the representativeness of these samples by comparing them with probabilistic samples of the same population. It is necessary to increase empirical studies to reach estimating propensity adjustments for volunteer web surveys as well as good practices should be indicated for building a successful convenience panel, to limit as much as possible the selection bias in web-survey and the use of propensity scores and, last but not least, useful approaches to ascertain on validity of inference from non-random sample.

If non-probability samples are to gain wider acceptance among survey researchers there must be a more coherent framework and accompanying set of measures for evaluating their quality. One of the key advantages of probability sampling is the measures and constructs so-called Total Sample Error (TSE) developed for it that provides ways of thinking about quality and error sources. TSE instruments to evaluate non-probability samples is not especially helpful because the framework for sampling is different. Arguably the most pressing need is for research aimed at developing better measures of the quality of non-probability sampling estimates that include bias and precision.

Notes

On October 2015 some newspapers published the news that the American Institute of Public Opinion—known as the Gallup Institute—would not carry out polls for the 2016 US presidential election. A few months later, a second US institute—the Pew Research Center—announced its withdrawal from electoral polls, citing the same reasons as the Gallup institute: namely the growing difficulties in selecting and interviewing a representative sample of voters. The managers of the two institutes explicitly admitted the impossibility of carring out accurate surveys since, compared to the past, the possibility of reaching representative samples of US voters was greatly diminished due to their fragmentation between mobile phones, the internet, micro-blogs, and the growing reticence or ambiguity of voters who in 85% of cases refused to answer the polls. It is no coincidence that today incentives of various kinds are envisaged to induce subjects to respond to a survey—the so-called online panels deserve a separate analysis (see further).

At the address: https://campionigratuiti.eu/sondaggi-retribuiti-online/ it is possible to find an a list of all the panels of online paid surveys.

This statement could be misunderstood affirming that all the web-surveys are based on self-selected samples. Our statement refers strictly to the electoral polls conducted in Italy in the period we considered. There are web-surveys that are actually based on probability samples (e.g. Bottoni and Fitzgerald 2021; Blom et al. 2016).

It is characterized by the flexible matching of the target population to a greater number of variables than is possible with traditional quota sampling. For this approach to be successful, a metric is used, the Euclidean distance, by which the composition of the stratified variables in the sample must reproduce exactly to the corresponding characteristics of the population.

Using a set of variables collected in several surveys, a propensity model is estimated by combining the samples and predicting the probability that each respondent belongs to a given survey. This model is applied to subsequent surveys by computing a propensity score for each respondent.

Rather than designing samples separately for each survey, respondents are invited to participate in an unspecified survey. The actual survey is determined dynamically based on the characteristics of each respondent and the needs of the active surveys with respect to quotas or selection criteria. This allows for more efficient use of the sample, but means that for each survey it depends on which other surveys are in progress at the same time.

The Italian regulation on the publication and dissemination of electoral polls on mass media lists the information that must be compulsorily included in the document that is published on the institutional website. These are the fifteen information items: title of the poll; subject who carried out the poll; client; buyer; date or period in which the poll was carried out; names of media that published or disseminated the poll; date of publication or diffusion; topics covered by the poll; target population; territorial extension of the poll; sampling method; representativeness of the sample, including indication of sample error; method of collecting information; sample size, number and percentage of non-respondents and substitutions; the full text of all questions and the percentage of people who answered each question.

It should be noted that from the information in our possession, derived from the information documents attached to the poll, it is not possible to distinguish between unsuccessful contacts due to outright refusals of the interview from those due to achievement of quotas or other reasons. This problem particularly concerns the interviews carried out with CATI or CAMI, thus significantly increasing the number of contacts.

References

AAPOR (American Association for Public Opinion Research): Report of the AAPOR Task Force on Non-Probability Sampling. June (2013)

AAPOR (American Association for Public Opinion Research): Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 7th edition (2011)

Alvarez, R., VanBeselaere, M., VanBeselaere, C.: Web-Based Surveys. The Encyclopedia of Measurement. California Institute of Technology (2005)

Asur, S., Huberman, B.A.: Predicting the Future with Social Media. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1003.5699v1 (2010)

Atkeson, L., Adams, A., Alvarez, R.: Nonresponse and mode effects in self- and interviewer-administered survey. Political Anal. 22(3), 304–320 (2014)

Bach, R.L., Eckman, S.: Motivated misreporting in web panels. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 6(3), 418–430 (2018)

Berinsky, A.J.: American public opinion in the 1930s and 1940s: the analysis of quota- controlled sample survey data. Public Opin. Q. 70(4), 499–529 (2006)

Berzofsky, M.E., Williams, R.L., Biemer, P.P.: Combining probability and non-probability sampling methods: model-aided sampling and the O*NET data collection program. Surv. Pract.. Pract. 2(6), 1–5 (2009)

Bethlehem, J.: Selection bias in web surveys. Int. Stat. Rev. 78(2), 161–188 (2010)

Bethlehem, J., Biffignandi, S.: Handbook of Web Surveys. John Wiley & Sons Inc, Hoboken, New Jersey (2012)

Bethlehem, J., Cobben, F., Schouten, B.: Handbook of Nonresponse in Household Surveys. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ (2011)

Biemer, P.B.: Total survey error: design, implementation, and evaluation. Public Opin. Q. 74(5), 817–848 (2010)

Biemer, P.B., Peytchev, A.: Census geocoding for nonresponse bias evaluation in telephone surveys: an assessment of the error properties. Public Opin. Q. 76(3), 432–452 (2012)

Biernacki, P., Waldorf, D.: Snowball sampling: problem and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 10(2), 141–163 (1981)

Blom, A.G., Bosnjak, M., Cornilleau, A., Cousteaux, A.S., Das, M., Douhou, S., Krieger, U.: A comparison of four probability-based online and mixed-mode panels in Europe. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev.comput. Rev. 34(1), 8–25 (2016)

Blumberg, S.J., Luke, J.V.: Coverage bias in traditional telephone surveys of low-income and young adults. Public Opin. Q. 71(5), 734–749 (2007)

Bosio, A.C.: Grazie, no!: il fenomeno dei non rispondenti. Quad. Sociol.sociol. 40(10), 31–44 (1996)

Bottoni, G., Fitzgerald, R.: Establishing a baseline: bringing innovation to the evaluation of cross-national probability based online panels. Surv. Res. Methods 15(2), 115–133 (2021)

Brick, J.M.: The future of survey sampling. Public Opin. Q. 75(5), 872–888 (2011)

Brick, J.M., Williams, D.: Explaining rising nonresponse rates in cross- sectional. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 645(1), 36–59 (2013)

Busse, B., Fuchs, M.: The components of landline telephone survey coverage bias. The relative importance of no-phone and mobile-only populations. Qual. Quant. 46(4), 1209–1225 (2012)

Callegaro, M., DeSogra, C.: Computing response metrics for online panels. Public Opin. Q. 72(5), 1008–1032 (2008)

Callegaro, M., Poggio, T.: Espansione della telefonia mobile ed errore di copertura nelle inchieste telefoniche. Polis 18(3), 477–506 (2004)

Chang, L., Krosnick, J.A.: National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet: comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opin. Q. 73(4), 641–678 (2009)

Copas, J.B., Li, H.G.: Inference for non-random samples. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 59(1), 55–95 (1997)

Couper, M.P., Kapteyn, A., Schonlau, M., Winter, J.: Noncoverage and nonresponse in an internet survey. Soc. Sci. Res. 36, 131–148 (2007)

Couper, M.P.: Web surveys: A review of issues and approaches. Public Opin. Q. 64(4), 464–494 (2000)

de Rada, V.D.: Effects (and defects) of the telephone survey in polling research: are we abusing the telephone survey? Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 108(1), 46–66 (2010)

Dever, J.A., Rafferty, A., Valliant, R.: Internet surveys: Can statistical adjustments eliminate coverage bias? Surv. Res. Methods 2(2), 47–62 (2008)

Deville, J.C., Särndal, C.E.: Calibration estimators in survey sampling. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 87, 376–382 (1992)

Di Franco, G.: Il campionamento nelle scienze umane. Teoria e pratica. FrancoAngeli, Milano (2010)

Di Franco, G.: Usi e abusi dei sondaggi politico-elettorali in Italia: Una guida per giornalisti, politici e ricercatori. FrancoAngeli, Milano (2018)

Di Franco, G., Santurro, M.: Machine Learning, Artificial Neural Network and Social Research. Quality and Quantity 55, 1007–1025 (2021)

Dillman, D.A., Phelps, G., Tortora, R., Swift, K., Kohrell, J., Berck, J., Messer, B.L.: Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the internet. Soc. Sci. Res. 38(1), 1–18 (2009)

DiSogra, C.: River Samples: A Good Catch for Researchers? GfK Knowledge Networks http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/accuracy/fall-winter2008/disogra.html (2008)

Duffield, N.: Sampling for passive internet measurement. A review. Stat. Sci. 19(3), 472–498 (2004)

Duffy, B., Smith, K., Terhanian, G., Bremer, J.: Comparing data from online and face-to-face surveys. Int. J. Mark. Res. 47(6), 615–639 (2005)

Dutwin, D., Buskirk, D.T.: Apples to oranges or gala versus golden delicious? Comparing data quality of nonprobability internet samples to low response rate probability samples. Public Opin. Q. 81(1), 213–239 (2017)

Elliott, M.R.: Combining data from probability and non-probability samples using pseudo-weights. Surv. Pract.. Pract. 2(6), 1–7 (2009)

Elliott, M., Haviland, A.: Use of a web-based convenience sample to supplement a probability sample. Surv. Methodol.. Methodol. 33(2), 211–215 (2007)

Erikson, R.S., Wlezien, C.: Are political markets really superior to polls as election predictors? Public Opin. Q. 72(2), 190–215 (2008)

Fricker, R.D., Schonlau, M.: Advantages and disadvantages of internet research surveys: evidence from the literature. Field Methods 14(4), 347–367 (2002)

Gittleman, S.H., Trimarchi, E.: Online Research… and All that Jazz! The Practical Adaptation of Old Tunes to Make New Music. ESOMAR, Amsterdam (2010)

Groves, R.M.: Survey Errors and Survey Costs. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York (1989)

Groves, R.M.: Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opin. Q. 70(2), 646–675 (2006)

Groves, R.M., Lyberg, L.: Total survey error. Past, present, and future. Public Opin. Q. 74(5), 849–879 (2010)

Groves, R.M., Presser, S., Dipko, S.: The role of topic interest in survey participation decisions. Public Opin. Q. 68(1), 2–31 (2004)

Handcock, M.S., Gile, K.J.: On the concept of snowball sampling. Sociol. Methodol.. Methodol. 41(1), 367–371 (2011)

Icc/Esomar: International Code on Market, Opinion and Social Research and Data Analytics. www.esomar.org (2016)

Itanes: Vox populi il voto ad alta voce del 2018. il Mulino, Bologna (2018)

Kalton, G., Flores-Cervantes, I.: Weighting methods. J. off. Stat. 19(2), 81–97 (2003)

Kish, L.: Survey Sampling. John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York (1965)

Kish, L.: Statistical Design for Research. John Wiley & Sons, New York (1987)

Kott, P.S.: Using calibration weighting to adjust for nonresponse and coverage errors. Surv. Methodol.. Methodol. 32(2), 133–142 (2006)

Kruskal, W., Mosteller, F.: Rapresentative sampling I. Int. Stat. Rev. 47, 13–24 (1979a)

Kruskal, W., Mosteller, F.: Rapresentative sampling II. Int. Stat. Rev. 47, 111–127 (1979b)

Kruskal, W., Mosteller, F.: Rapresentative sampling III. Int. Stat. Rev. 47, 245–265 (1979c)

Kruskal, W., Mosteller, F.: Rapresentative sampling, IV: the history of the concept in statistics 1895–1939. Int. Stat. Rev. 48, 169–195 (1980)

Lee, S.: An evaluation of nonresponse and coverage errors in a web panel survey. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev.comput. Rev. 2(4), 460–475 (2006a)

Lee, S.: Propensity score adjustment as a weighting scheme for volunteer panel web surveys. J. off. Stat. 22(2), 329–349 (2006b)

Lee, S., Valliant, R.: Estimation for volunteer panel web surveys using propensity score adjustment and calibration adjustment. Sociol. Methods Res. 37(3), 319–343 (2009)

Link, M.W., Lai, J.W.: Cell-phone-only households and problems of differential nonresponse using an address-based sampling design. Public Opin. Q. 75(4), 613–635 (2011)

Marradi, A.: Casualità e Rappresentatività di un campione nelle scienze sociali: contributo a una sociologia del linguaggio scientifico. In: Mannheimer, R. (ed.) I sondaggi elettorali e le scienze politiche. Problemi Metodologici. FrancoAngeli, Milano, pp. 51–133 (1989)

Marradi, A.: Casuale e rappresentativo: ma cosa vuol dire? In: Ceri. P. (ed.) Politica e sondaggi. Rosenberg & Sellier, Torino, pp. 23–87 (1997)

Mercer, A.W., Kreuter, F., Keeter, S., Stuart, E.A.: Theory and practice in nonprobability surveys: parallels between causal inference and survey inference. Public Opin. Q. 81(1), 250–271 (2017)

Miller, P.V.: Is there a future for surveys? Public Opin. Q. 81(1), 205–212 (2017)

Olson, K.: Survey participation, nonresponse bias, measurement error bias, and total bias. Public Opin. Q. 70(5), 737–758 (2006)

Revilla, M.: Comparison of the quality estimates in a mixed-mode and unimode design: an experiment from European social survey. Qual. Quant. 49(6), 1219–1238 (2015)

Sakshaug, J.W., Schmucker, A., Kreuter, F., Couper, M.P., Singer, E.: The effect of framing and placement on linkage consent. Public Opin. Q. 83(S1), 289–308 (2019)

Schonlau, M., van Soest, A., Kapteyn, A., Couper, M.: Selection bias in web surveys and the use of propensity scores. Sociol. Methods Res. 37, 291–318 (2009)

Smith, T.M.F.: On the validity of inferences from non-random sample. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 146(4), 394–403 (1983)

Sudman, S.: Probability sampling with quotas. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 20, 749–771 (1966)

Valliant, R., Dever, J.A.: Estimating propensity adjustments for volunteer web surveys. Sociol. Methods Res. 40(1), 105–137 (2011)

Wejnert, C., Heckathorn, D.D.: Web-based network sampling: efficiency and efficacy of respondent-driven sampling for online research. Sociol. Methods Res. 37(1), 105–134 (2007)

Yeager, D.S., Krosnick, J.A., Chang, L., Javitz, H.S., Levendusky, M.S., Simpser, A., Wang, R.: Comparing the accuracy of RDD telephone surveys and internet surveys conducted with probability and non-probability samples. Public Opin. Q. 75, 709–747 (2011)

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The author declares that no funds, grants, or other support were received in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no material financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

The stydy was conducted by analyzed public access data published on the institutional website of Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers at: www.sondaggipoliticoelettorali.it

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Franco, G. The return of non-probability sample: the electoral polls at the time of internet and social media. Qual Quant (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01835-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-024-01835-8