Abstract

This paper’s goal is to discuss implications for the empirical study of low educational status arising from the use of the concept of educational poverty in research. It has two related conceptual foci: (1) the relationship of educational poverty with material poverty and to what extent useful parallels exist, and (2) the distinction of absolute and relative (educational) poverty and whether the notion of absolute (educational) poverty is a sensible one. For the concept of educational poverty to be analytically fruitful, clear conceptualisation and operationalisation of the relevant issues are required. The paper contributes to the aim of providing these by building on existing work on educational poverty and by drawing on relevant work on material poverty as well as discussing some conceptual challenges and some of the challenges arising from the operationalisation of the concepts. Some of these challenges are illustrated using examples based on data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). In a further step, factors which may lead to a greater risk of being in relative educational poverty are analysed, employing the method multi-value Qualitative Comparative Analysis. The empirical findings highlight the relative nature of educational qualifications: the usefulness of a basic school leaving qualification has changed over time, and it has not been the same for different groups. Thus, a conceptualisation of low educational status as educational poverty has been shown to be useful, and it has been demonstrated that the relative nature of educational poverty ought to be taken into account by researchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Poverty in the sense of material poverty is an everyday term. While the details of an expert definition of material poverty may differ from the way it is understood by lay people, the concept will be immediately understood by everyone more or less in the way in which it is intended. The term “educational poverty”, on the other hand, has not entered everyday vocabulary. This concept was introduced into academic discourse by Allmendinger (1999) and, up to now, it has mostly been taken up by German and other continental European scholars (e.g., Lohmann and Ferger 2014; Solga 2011; Blossfeld et al. 2019; Quenzel and Hurrelmann 2019a). Given that it is distinct from the concept of inequality in education,Footnote 1 it has the potential to be an additional conceptual tool for analysing the role of education in enabling participation in modern society. Throughout this paper, educational poverty will be understood as a lack of formal qualificationsFootnote 2 which precludes participation in the labour market (and possibly affects other spheres of life such as family life and health) in a way not experienced by individuals with higher levels of education.

Education and the certification of education in the form of qualifications are more important than ever, given technological progress and the accompanying demand for a highly skilled workforce. This tight coupling of skills and job opportunities suggests that the labour market is likely to be the most important area of life on which education has an impact. In addition, there is some evidence that educational status matters in other areas, too: Solga (2011) reports lower rates of marriage and, among those who do marry, higher rates of divorce for individuals with a low level of qualifications. They also remain childless more frequently than people with higher qualifications, but, conversely, they are also more likely to experience parenthood during their teenage years. In addition, their health tends to be worse (Quenzel and Hurrelmann 2019b).

In research on material poverty, a distinction is commonly made between absolute and relative poverty, with the latter defining poverty in relation to some standard which can vary between points in time and between societies. As can be seen from the connection between education and the labour market noted above, it seems plausible that this distinction might also be relevant to educational poverty, since the effect on an individual’s life of their educational status is likely to be at least partially dependent on how important educational status is in a particular labour market. Indeed, the relative value of educational qualifications (and other material and immaterial resources) has been discussed extensively (key authors are Dore 1976; Hirsch 1976; see also, e.g., Thurow 1977), though a lack of formal qualifications has not been explicitly conceived as educational poverty by these authors.

This paper’s goal is to discuss implications for the empirical study of low educational status arising from the use of the concept of educational poverty—developed analogously to material poverty—in such research. It has two related conceptual foci: (1) the relationship of educational poverty with material poverty and to what extent useful parallels exist, and (2) the distinction of absolute and relative (educational) poverty and whether the notion of absolute (educational) poverty is a sensible one. For the concept of educational poverty to be analytically fruitful, clear conceptualisation and operationalisation of the relevant issues are required. This paper contributes to the aim of providing these by building on existing work on educational poverty (see above: Allmendinger 1999; Blossfeld et al. 2019; Lohmann and Ferger 2014; Solga 2011) and by drawing on relevant work on material poverty as well as discussing some conceptual challenges and some of the challenges arising from the operationalisation of the concepts. I will illustrate some of these challenges using examples based on data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). In a further step, again drawing on NEPS data, I will analyse three factors which may lead to a greater risk of being in relative educational poverty. They are sex, school qualification, and cohort (i.e., whether someone was born by 1965 or later). Sex is of interest because of the differing experiences of men and women over time (e.g., Blossfeld et al. 2019), school qualifications are a prerequisite for most forms of post-school qualification and, in addition, they can be used by employers offering apprenticeship as a screening device, with higher school qualifications presumed to indicate greater suitability for an apprenticeship, and cohort matters because of the changing context in which qualifications are obtained and used (e.g., Lohmann and Ferger 2014). Clearly, other factors are likely to be involved in educational poverty (though the literature on what these may be is not very detailed), but given the need, for analytical reasons, to restrict the number of factors, I am concentrating here on ones of particular theoretical interest.

2 Challenges

2.1 Conceptual issues

2.1.1 Material versus educational poverty

Poverty, as noted in the Introduction, is commonly understood to refer to material poverty, and I therefore begin by discussing the relationship between material and educational poverty, noting similarities and differences. Peter Townsend, the renowned scholar in the field, describes poverty thus: “Individuals, families and groups in the population can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the type of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and the amenities which are customary, or at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong. Their resources are so seriously below those commanded by the average family that they are in effect excluded from ordinary living patterns, customs and activities.” (Townsend 1979, p.31) Clearly, material poverty affects nearly all spheres of life (including, of course, education as part of a reciprocal relationship: children growing up in poverty are less likely to obtain a high level of education, and individuals with low levels of education are more likely to experience poverty because of their greater difficulties in obtaining adequately-paid work). As I noted in the Introduction, insofar as educational status affects an individual’s opportunities in the labour market, educational poverty can also be expected to affect a wide range of areas of life, restricting societal participation in a variety of ways.

One feature of material poverty is that it is not always stable. Some individuals move in and out of poverty, for example because they lose and find work repeatedly. In fact, Townsend (1979, pp.56/57) notes that the proportion of the population who are always poor is smaller than that of those who experience occasional spells of poverty, but who do not remain poor permanently. In addition, many more people live “under the constant threat of poverty and regard some of the resources flowing to them, or available to them, as undependable” (p. 57).Footnote 3 By contrast, educational resources are likely to be more stable. Once someone obtains a qualification, they will not lose it again, it remains linked to the person. While it is possible to move out of educational poverty by gaining qualifications later in life, these then cannot be lost either. However, relative to the demands of the labour market, qualifications may decrease in value over an individual’s lifetime: a level of qualification which would have been deemed sufficient at the beginning of someone’s working life may later on be considered insufficient with regard to the changing demands of the labour market. In that sense, the person would become educationally poor over time, but this would be a more gradual process compared to the possible fluctuations described by Townsend in relation to material poverty.Footnote 4 In a similar way, what would count as educationally not poor for parents might be seen as educationally poor for their children.

Another obvious difference between material and educational poverty is that it is perfectly possible to transfer money to people who are considered unacceptably poor (political will and availability of funds permitting, though given individuals’ life situations, the ameliorating effects of such transfers cannot be guaranteed). But it is not possible simply to transfer “education” onto people who have been unable to achieve some minimum standard (at least not legitimately). It is possible to implement educational programmes to allow them to catch up, but with no guarantee of success.

2.1.2 Relative versus absolute educational poverty

Rowntree (quoted in Townsend 1979, p.33) defines families whose “total earnings are insufficient to obtain the minimum necessaries for the maintenance of merely physical efficiency as being in primary poverty”. Clearly, this describes a state of deprivation which would be considered as poverty regardless of historical period, society or political context, in other words, it is an absolute conceptualisation of poverty. Townsend (and others), however, does not agree that there is such a thing as absolute poverty. Instead, he goes on to show that the “minimum necessaries” can only ever be determined relative to the societal standard relevant at the time, coming to the conclusion that “… definitions which are based on some conception of ‘absolute’ deprivation disintegrate upon close and sustained examination and deserve to be abandoned. … In fact, people's needs even for food are conditioned by the society in which they live and to which they belong, and just as needs differ in different societies so they differ in different periods of the evolution of single societies. Any conception of poverty as ‘absolute’ is therefore inappropriate and misleading” (p. 38).Footnote 5 We can see a parallel with educational poverty: illiteracy would clearly seem to qualify as a definition of absolute educational poverty, as would a complete absence of qualifications. However, there were historical periods during which illiteracy would not have prevented an individual from participation in normal societal activities, and a lack of formal qualifications certainly would not have done so, so illiterate individuals and those lacking formal qualifications would not have been considered educationally poor (in fact, the concept itself would have been meaningless). Furthermore, the phenomenon of “illiteracy” can be discussed as illiteracy, an alternative conceptualisation as “educational poverty” is not needed. On the other hand, in many societies today it is perfectly possible to have basic literacy and even some educational certificates and still be considered educationally poor. It seems, then, that Townsend’s concerns re absolute material poverty apply equally to the concept of educational poverty which has to be defined relative to the historical period and the societal context in which the individual lives.

In introducing the concept of educational poverty, Allmendinger (1999) nevertheless takes up the distinction between absolute and relative poverty, defining absolute minimum standards of educational qualifications for each country under study, with those falling below this standard considered educationally poor.Footnote 6 She then defines relative educational poverty by referring to the distribution of educational certificates in the relevant country or society. Blossfeld et al. (2019), drawing on Allmendinger, also distinguish between absolute and relative educational poverty, though their empirical analysis based on NEPS data only considers absolute educational poverty. According to Quenzel and Hurrelmann (2019b), this is a common way of proceeding, with many scholars discussing the conceptual difference between absolute and relative poverty, but then ignoring the distinction in their empirical analyses.

The fact that the distribution of resources (for material poverty) or educational certificates (for educational poverty) is employed as a standard against which relative poverty may be defined shows the connection between inequality and poverty, since inequality is also assessed by referring to the distribution of relevant resources. However, a large amount of inequality is not in itself an indicator of a large amount of poverty, since a few very rich individuals at the top end of the distribution can co-exist with individuals at the bottom end of the scale who have the resources to lead a way of life which is much more restricted, but not necessarily deprived in the sense described by Townsend. The difference between material poverty and material inequality does not arise so much from a difference in empirically demonstrable phenomena, but from the angle from which the issue is viewed: inequality focuses on distribution, whereas (relative) poverty is defined against a standard of behaviour (such as the tea drinking example offered by Townsend, see footnote 5). The latter of course partly depends on the distribution of resources—what is considered a normal standard of behaviour is linked to whether people have the resources to enable them to act on this standard—but it can be expected to be more stable since temporary changes in circumstances would not immediately alter such a behavioural standard. Turning to education, Lohmann and Ferger (2014) argue that the difference in focus between inequality and poverty is that “research on educational inequalities […] is primarily concerned with inequalities of opportunity”, while “research on educational poverty focuses on inequalities of condition” (p. 1).

Finally, in the context of a discussion of the relative position of individuals, whether regarding their material or immaterial resources such as educational certificates, it is important to acknowledge existing work in this area, especially that by Fred Hirsch (1976) on positional goods and Ronald Dore (1976) on qualifications inflation. Hirsch analyses the way in which the value of certain material as well as immaterial goods depends at least partly on how many other people have access (or not) to the same goods. An example is driving a car: if just one person drives their car, they will get to their destination more quickly than if they used slower means of transport, but if everybody drives, there will be congestion, slowing everybody down. Hirsch also discusses education, where the value of credentials partly depends on the number of people holding the same credentials, given the use of credentials as a screening device. Dore’s entire focus is on educational credentials. He demonstrates and discusses, amongst other things, how a surplus of individuals with a certain level of qualification against a background of a shortage of jobs at the relevant level can change the educational requirements for jobs: even if the demands of the job itself do not change, an employer may well demand higher levels of qualifications from applicants simply to be able to select candidates from a large pool of applicants. Clearly, this analysis matters for the exploration of educational poverty: what Dore describes can happen at any level, including that of the least qualified individuals who may see their employment opportunities diminish with rising qualifications among their competitors. Thus, they are being rendered (relatively) educationally poor without a change in their own qualifications.

2.2 Empirical issues

2.2.1 Data: National Educational Panel Study (NEPS)

Since I am going to illustrate some of the conceptual points made in the previous section by drawing on empirical examples, I first describe briefly the data I employ throughout the paper. The data come from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort Adults, https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC6:11.0.0. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data was collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network (see also Blossfeld and Roßbach 2019). Its aim is to collect longitudinal data on all aspects of education in formal and informal contexts, covering certificates as well as competences, and enabling researchers to investigate causes and consequences of educational outcomes. Data are collected in six cohorts, covering respondents at birth, at the start of nursery, in school years 5 and 9, at the start of university, and as adults. General data collection started in 2011, with new waves added every 1 or 2 years. For the adult cohort, on which the present paper draws, data collection actually started as early as 2007, and the data include, amongst other things, retrospective information on educational experiences and data on parents’ educational and occupational statuses. The present paper uses data on respondents with no missing data on respondent’s education, joint parental education and joint parental class, n = 15,413.Footnote 7

2.2.2 The relationship between cognitive ability and educational certificates

Up to now, the discussion of educational poverty has centred on poverty of certificates, since certificates are what employers usually draw on in selecting employees. Given that a large part of the effects of educational poverty is mediated by labour market experiences, this is clearly an important aspect of educational poverty. It is also relatively easy to measure. However, attention should also be paid to cognitive ability and competences, since it seems plausible that they can affect the same outcomes, i.e. labour market opportunities, health, and family. Indeed, a number of researchers discuss both poverty of certificates and poverty of competences in their work on educational poverty (e.g., Blossfeld et al. 2019; Lohmann and Ferger 2014; Quenzel and Hurrelmann 2019b; Solga 2011). The NEPS data contain a good range of competence measures; however, the difficulty is that these were obtained in adulthood, well after educational certificates were obtained (or not). But competences affect which certificates are obtained, rather than the other way round which makes the adult cohort NEPS dataFootnote 8 unsuitable for investigating this relationship. In principle, it is possible to analyse the role of poverty of competences for, say, labour market outcomes, but given that such outcomes are likely to be at least equally strongly affected by certificates, this makes the analysis of the role of competences difficult in practice because the two measures are so closely intertwined. In addition, some attention will need to be paid to the mechanism by which competences can have effects on people’s experiences: in the labour market, a prospective employer does not usually have access to someone’s performance on a cognitive or competence test, so they rely on certificates as a proxy for competence.

2.2.3 Measurement

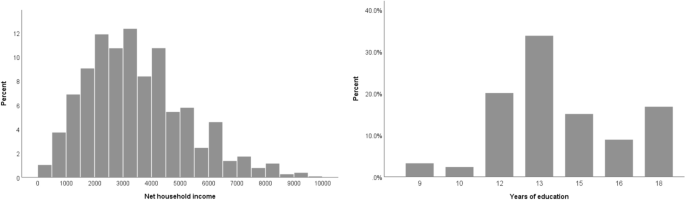

The problem described in the previous paragraph is one where, in principle, it is possible to collect the data necessary to address it. In what follows, the nature of the problem lies in the nature of the measure rather than the process of data collection: educational poverty, understood as a shortage of qualifications so severe that it restricts societal participation, cannot be measured in the same way as material poverty. The main basis for measuring material poverty is income or resources in the form of money, with non-monetary resources such as benefits in kind sometimes taken into consideration. Money is easily measured on an interval scale. Level of education,Footnote 9 by contrast, is frequently indicated either by years of education or by highest qualification obtained. The former is not necessarily very helpful especially in systems with a high degree of educational stratification, since the type of qualification achieved is more meaningful than the time taken to achieve it. If anything, taking a greater number of years to achieve a certain qualification may actually be interpreted negatively compared with someone who takes a shorter period of time to achieve the same formal level, so using years of education as an indicator of educational achievement would be counterproductive. But even in systems with a low degree of stratification, years of education is highly correlated with level of education, thus not adding much extra information. At first glance, years of education appear to be measurable on an interval scale, but the range is very restricted, the distribution uneven, and the meaning of one additional year of education is not the same at each point of the scale. Table 1 and Fig. 1 illustrate the differences between income and years of education, two measures used to indicate material and educational poverty respectively, using NEPS data. It can be seen that, indeed, while using an interval scale appears appropriate for measuring income, years of education has only seven values and a concentration of the majority of cases in just two of them, 12 and 13. It also has a far smaller range than the income scale.

Highest qualification obtained, by contrast, is measured on an ordinal scale. It has the advantage of being relatively straightforward to measure and to interpret, at least by people familiar with the relevant educational system, but a mean cannot be calculated in a meaningful way (though mode and median are viable alternative measures of central tendency). Instead, simple frequencies and percentages of individuals in the different ordered categories form the key measures of interest, as in Table 2.

The German qualifications are listed in Table 2 in ascending order of status. Hauptschule is the most basic form of school in the German tripartite system, offering a qualification which allows the recipient to enter vocational training for mostly manual trades. Mittlere Reife is the qualification offered by the intermediate school type of Realschule, suitable for most forms of vocational training.Footnote 10

These different forms and levels of measurement have implications for the operationalisation of concepts of interest, as I discuss in the next section.

2.2.4 Operationalisation

With respect to relative material poverty, there appear to be two—related and not entirely distinct—ways of operationalising the concept. One is fairly widespread. It relies on income distribution and defines a poverty line which is some percentage (50 or 60 percent) of the median income. Anyone below this line is considered poor. The other way relies on substantive criteria which describe the situation of someone living in relative poverty. Townsend describes in some detail relevant considerations in deciding upon a standard which separates (relatively) materially poor from (relatively) non-poor individuals, and it becomes clear that, while he does discuss income-based definitions, income alone cannot form the basis of a definition of material poverty. Instead, societal norms define obligations people are expected to meet. There is no single criterion which determines poverty status, instead, there is a “pattern of non-observance [of social customs which] may be conditioned by severe lack of resources” (p. 57). Thus, operationalising poverty solely based on income distribution is potentially misleading because it may not capture actual differences in the experience of living conditions. Using a poverty line based on the median income to determine whether or not someone is experiencing poverty has the effect of their being designated poor (or not) with rising and falling average incomes, even if neither their own incomes change nor, more importantly, their situation in terms of what they can afford or whether they can participate in normal societal activities (see also footnote 3) (for the problems associated with using a single dimension to create an indicator of a complex concept such as poverty, see also Berg-Schlosser 2018). The advantage, however, of an income-based poverty line is that it is fairly straightforward to measure and, despite the reservations noted here, it is likely to capture fairly accurately the situation experienced by poor people in the sense that normal participation in socially expected and accepted activities is likely to be difficult if not impossible given an income below the poverty line. In addition, what are socially expected and accepted activities will at least partly depend on what most people are able to afford, thus income distribution is relevant in that respect. However, as an alternative to a solely distribution-based measure, it is possible to construct a list of goods and activities, along with their cost, which together constitute a range of “normal” societal activities. Their combined cost would constitute a criterion-based poverty line, in other words, a threshold below which an individual or household would be considered relatively poor.

What are the implications for the operationalisation of educational poverty? Absolute educational poverty seems impossible to operationalise given that education always has its effects in social and historical context. Allmendinger (1999) suggests that everyone having less education (indicated through certificates) than the population average might be defined as educationally (relatively) poor, and this, according to her, would suggest that all those in the lowest quartile or quintile of the distribution would fulfil this criterion. However, using such a distribution-based measure would ignore substantive criteria such as those suggested above in relation to material poverty. In addition, Table 2 shows that the distribution of certificates can be very uneven, making it difficult to define “the average of the population” or a clear cut-off point.Footnote 11 It would seem more appropriate to consider substantive criteria in defining educational poverty, taking account of what certificates are needed to participate in normal social activities, including the labour market which is likely to be the sphere of life in which education has the greatest impact.

3 Method

The method used for the analysis shown below is Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) in its multi-value (mvQCA) variant. I do not have space here to fully explain this method, but the references given in this section should be helpful to readers unfamiliar with it. The interpretation of the findings as I present them will also help the reader understand the method.

Briefly, then, QCA was developed by Charles Ragin (Ragin 1987, 2000, 2008, see also, e.g., Rihoux and Ragin 2009; Rihoux 2020). Based on set theory and Boolean algebra, it offers a way of systematically analysing conjunctions of factors as potential necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome. Data are arranged in a truth table which shows all the possible combinations of values on the conditions under study and their relationship with the outcome. This truth table forms the basis for Boolean minimisation which is a way of logically summarising all the possible combinations of factors leading to the outcome. Ragin developed crisp and fuzzy variants of QCA, with the former employing dichotomous variables indicating full membership or non-membership in a set, and the latter allowing partial membership of a set. Lasse Cronqvist introduced another QCA variant: in multi-value QCA (mvQCA) crisp sets with more than two categories may be used (Cronqvist 2003; Cronqvist and Berg-Schlosser 2009). Originally developed for the use with small to medium n, QCA has since been usefully employed with large n (e.g., Cooper 2005; Glaesser and Cooper 2011; Greckhamer et al. 2013; Ragin 2006; Ragin and Fiss 2017). QCA’s strengths are that it enables the researcher to analyse systematically complex connections amongst factors, allowing for multiple pathways to the outcome and investigating the effects of combinations of factors. I use the mvQCA variant in this paper because it is the most suitable for the type of data I analyse: since some of my factors have more than two categories, crisp set QCA would not be suitable (it is possible to employ dummies, but this makes the analyses clumsy and the findings harder to interpret). In order to use fsQCA, on the other hand, I would have had to decide how to calibrate the school qualification measure. Any decision taken in calibration affects the results, whereas the categories used in the mvQCA have substantive meanings which are straightforwardly interpretable. The analysis was performed using the R package QCApro (Thiem 2018).Footnote 12

4 Relative educational poverty: some empirical findings

Clearly, it is important to consider the relative nature of the value of educational certificates despite the challenges associated with operationalising relative educational poverty discussed above. As we have seen, this value changes over time: on the one hand, technological change leads to a change in the structure of the labour market in modern societies, so that there will be a demand for more highly skilled workers, on the other hand, educational expansion has produced an oversupply of candidates with high formal qualifications, a development which leads to lowly qualified candidates being rejected for jobs which previously had been carried out perfectly competently by workers with this level of qualification (Dore 1976). Taken together, these two developments lead to a devaluing of basic qualifications in the labour market.

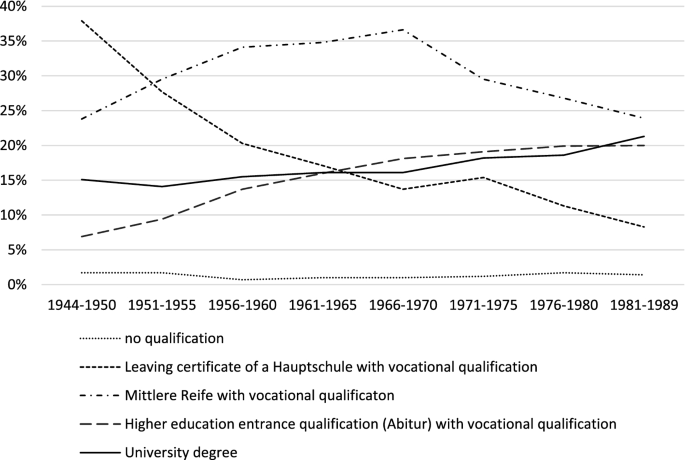

4.1 Descriptive results

Qualifications inflation is evident in the NEPS data when considering changes over eight cohorts, ranging from those born between 1944 and 1950 to those born between 1981 and 1989: Hauptschulabschluss (HS) with vocational qualification was the most common qualification in the earlier cohorts. The proportion of respondents with this qualification then fell from 38% (1944–1950) to 8.3% (1981–1989). The combination Abitur (i.e., the Higher Education entrance qualification) with vocational qualification went from fairly uncommon (6.9% for the 1944–1950 cohort) to one held by a fifth of respondents (20.0% for the 1981–1989 cohort). Finally, having a university degree went from a qualification held by 15.1% of the 1944–1950 cohort to being the second most common one at 21.3% (only surpassed by Mittlere Reife with vocational qualification at 23.9%) for the 1981–1989 cohort. Over time, the proportions of respondents with Hauptschulabschluss who have remained without vocational qualification have increased, from 9.9% in the oldest cohort to 29.2% in the youngest. Figure 2 summarises some of these developments, and it is worth noting that what has sometimes been defined as absolute educational poverty—the absence of any qualification—has remained fairly constant over time. This is represented by the dotted line in Fig. 2.

The two developments taken together—the seemingly greater risk for Hauptschulabschluss holders of remaining without a vocational qualification and the increasing number of Abitur holders who obtain vocational qualifications—may largely reflect changes in the composition of these groups. Presumably, Hauptschulabschluss is increasingly only obtained by individuals who struggle in some way—whether academically or in life more generally—so that they are unable or unwilling to gain a vocational qualification. Employers who can offer apprenticeships are more likely to offer their places to Mittlere Reife or Abitur holders given that there are enough candidates with these higher levels of qualifications. This may be because they use qualification as a simple screening device when faced with a large number of applicants, and/or because they fear that the group of Hauptschulabschluss holders is indeed negatively selected for academic ability and/or motivation (see Solga 2011, p.430, who also discusses such developments).

These descriptive findings suggest that it would be interesting to analyse the joint contributions of various factors to educational status, investigating how this has changed over time. Employing mvQCA, I will make use of the idea of the relative nature of the value of educational certificates as described at the beginning of this section in analysing the outcome of “post-school qualification”. This refers to attaining a qualification recognised in the labour market (i.e., either a vocational qualification or a degree). With its tightly regulated labour market, it is fairly difficult in Germany to obtain stable employment without such a qualification which makes this an important outcome. Post-school qualification (“POST.SCHOOL”) is coded 1 = “has vocational qualification or degree”, 0 = “has no post-school qualification”.

4.2 mvQCA results

As I explained in the Introduction, I used three factors as the conditions in the mvQCA analysis. Given that a focus on context and interactions is a core principle of QCA (which is the reason I chose it as my method of analysis), it would not make sense to state hypotheses concerning the likely effects of individual conditions. Instead, I comment briefly on how they might be expected jointly to be linked to the outcome: This paper’s key focus is on relative educational poverty. Accordingly, one of the three conditions is cohort, since I expect the role of education—more specifically, of the lowest qualification, Hauptschule—to change over time, with Hauptschule possibly being sufficient for reaching some post-school qualification for the older cohort, but not the younger. At the same time, it is plausible that male sex will be part of a configuration which is sufficient for obtaining a post-school qualification for the older cohort, but that it loses its relevance for the younger cohort. As for necessity, I do not expect any of the three conditions to be individually necessary for the outcome given that it has been fairly common in all age groups across a variety of subgroups, though it is plausible that a disjunction of several factors will be.

Sex (“MALE”) is coded 1 = “male” and 0 = “female”,Footnote 13 school qualification (“SCHOOL.QUAL”) is coded 0 = “no qualification”, 1 = “Hauptschule”, 2 = “Mittlere Reife”, 3 = “Abitur”, and cohort (“COHORT”) is coded 0 = “born 1944–1965” and 1 = “born 1966–1989”. Table 3 is the truth table, showing the 16 possible combinations of these three factors. The column headed “outcome POST.SCHOOL” indicates whether or not the respective row has reached the threshold for consistency with sufficiency.Footnote 14 This threshold is set by the researcher, depending on how close to perfect sufficiency a relationship is desired. It can be informative to explore more than one threshold in order to get a sense of the interplay of factors (an approach used, for example, by Cooper 2005), taking account of jumps in consistency. In Table 3, there is a gap between configurations 0 2 0 (consistency 0.917) and 1 1 1 (consistency 0.849), and again between configurations 0 1 0 (consistency 0.848) and 0 1 1 (consistency 0.745), suggesting that 0.9 and 0.8 are useful places to set thresholds. These are reflected in the entries 1/0 in the column headed “outcome”.

The column headed “n” gives the number of cases with the combination described in this truth table row. The final column headed “consistency” gives the consistency with sufficiency for each row. In the case of crisp and mvQCA, this figure is simply the proportion of cases in the row with the outcome. So, for example, the first row contains the 1276 cases who are male, have a Mittlere Reife qualification as their highest school qualification and who belong to the older cohort. 96.3 percent of them obtained a post-school qualification. Given that the truth table is ordered in descending order of consistency, the rows with the highest proportion of cases obtaining a post-school qualification are found nearer the top of the table.

There are some interesting insights to be gained merely from studying the truth table. We can see that it is fairly common to obtain a post-school qualification: in most groups, over 90 percent achieve this. Respondents whose highest qualification is a Hauptschulabschluss are the exception: the only row containing Hauptschule leavers with a consistency above 0.9 is the combination 1 1 0, i.e. men from the older cohort. They obtain post-school qualifications in similar proportions to cases with higher school qualifications.Footnote 15

The truth table can now be used to generate two Boolean solutions in a process of minimisation to obtain (quasi-)necessary and (quasi-)sufficient combinations of conditions for achieving the outcome. In the first, employing a threshold of 0.9 for consistency with sufficiency, no quasi-necessary combination of conditions was found (as indicated by the single-headed arrow). The combination of Mittlere Reife OR Abitur OR [male AND Hauptschulabschluss AND older cohort] was quasi-sufficient for obtaining a post-school qualification. In other words, there are three routes to the outcome at this consistency level: (1) Abitur, (2) Mittlere Reife, (3) Hauptschulabschluss combined with being male and a member of the older cohort. The second solution, employing a threshold of 0.8, shows a combination of conditions which are jointly (quasi-)necessary and (quasi-) sufficient for the outcome, as indicated by the double-headed arrow. They are Mittlere Reife OR Abitur OR [male AND Hauptschulabschluss] OR [Hauptschulabschluss AND older cohort]. The figures given below, on a scale of zero to one, provide information on the consistency with sufficiency for every combination of conditions (the column headed “incl”) and raw and unique coverage (in the columns headed cov.r and cov.u, respectively). The coverage figures indicate the empirical relevance of each combination of conditions, with unique coverage calculatedFootnote 16 for cases who only have the conditions specified by the particular path, and raw coverage for those on the path who also have conditions specified by other paths.

4.3 Solutions

-

(1)

Threshold of 0.9 consistency with quasi-sufficiency.

SCHOOL.QUAL{2} + SCHOOL.QUAL{3} + MALE{1}*SCHOOL.QUAL{1}*COHORT{0} = > POST.SCHOOL

incl

cov.r

cov.u

1

SCHOOL.QUAL{2}

0.936

0.340

0.340

2

SCHOOL.QUAL{3}

0.935

0.449

0.449

3

MALE{1}*

SCHOOL.QUAL{1}*COHORT{0}

0.935

0.091

0.091

Model

0.936

0.880

-

(2)

Threshold of 0.8 consistency with quasi-sufficiency

SCHOOL.QUAL{2} + SCHOOL.QUAL{3} + MALE{1}*SCHOOL.QUAL{1} + SCHOOL.QUAL{1}*COHORT{0}<=> POST.SCHOOL

incl

cov.r

cov.u

1

SCHOOL.QUAL{2}

0.936

0.340

0.340

2

SCHOOL.QUAL{3}

0.935

0.449

0.449

3

MALE{1}*SCHOOL.QUAL{1}

0.910

0.124

0.034

4

SCHOOL.QUAL{1}*COHORT{0}

0.896

0.158

0.067

Model

0.926

0.980

The analyses show the relevance of context: not surprisingly, Mittlere Reife and Abitur are both (quasi-)sufficient conditions on their own for gaining a post-school qualification regardless of cohort, but Hauptschulabschluss, the most basic form of school qualification, was not sufficient for most cases, only for men from the older cohort. This latter group corresponds to the fifth truth table row. When a slightly less stringent threshold for sufficiency is chosen, then only one of the two factors, sex and cohort, had to be combined with Hauptschulabschluss, but it still was not sufficient on its own.

5 Discussion

Poverty can be employed as an emotive term to stress the seriousness of an individual’s situation. Such a usage would seem to be more appropriate for political campaigners rather than for researchers striving for neutrality and objectivity. In addition, describing someone as poor may lead to their being stigmatised and written off. Having said that, the conceptual discussion in this paper has shown that, despite key differences with material poverty, the concept of poverty is useful in describing a situation where someone is excluded from participation in what is considered normal in the society in which they live. Understood in this way, it makes sense to talk about educational poverty as a lack of formal qualifications which severely restricts participation in a number of areas of social life as defined in the Introduction, a definition I drew upon throughout this paper.

What has also become clear from the conceptual discussion is that educational poverty, like material poverty, ought to be understood as a relative concept. While the distinction between absolute and relative poverty has been made by a number of scholars (e.g., Allmendinger 1999; Blossfeld et al. 2019; Sen 1983), in practice they still describe even absolute poverty by referring to the context in which it is experienced. Clearly, then, it is important that in analysing educational poverty, we do not lose sight of its relative nature. A particular level of education may have been perfectly adequate during an earlier period, only for the same level to represent educational poverty in an age in which more and more people acquire ever higher levels of formal education. Equally clearly, different groups can be affected differentially at different times and in different societies, so that what constitutes educational poverty for one may not have the same implications for another.

Empirically, the shifts in educational qualifications analysed descriptively in Sect. 4.1 already show that distribution matters: a Hauptschule qualification followed by a vocational qualification has gone from being the most commonly held type of qualification to being fairly unusual over the course of the observation period. Quenzel and Hurrelmann (2019b) describe clearly how this development is associated with the job opportunities of people whose highest school qualification is a Hauptschulabschluss, noting that the composition of this group has become more homogeneous over the years, with most of them coming from educationally deprived households. Apart from the implications for their educational opportunities, this also means that they have fewer informal networks to draw on to help them in their job search. At the same time, employers use school qualification as a screening device, assuming—rightly or wrongly—that an individual from such a negatively selected group is less likely to fulfil their requirements compared to someone from the much larger pool of individuals with higher levels of qualification. The QCA analysis (Sect. 4.2) confirms empirically the importance of a relative conceptualisation of educational poverty: since gaining a post-school qualification will greatly ease the transition into the labour market, it is one of the outcomes which ought to be considered in analysing potential effects of educational poverty. As I was able to show, the value of Hauptschulabschluss has not remained the same: it was a (quasi-) sufficient condition (at the 0.9 level) for obtaining the outcome of a post-school qualification only for a certain group—men—and during a certain period of time—that in which respondents born before 1966 completed their schooling. This means that, for women born at any point in time and for both men and women born after 1965, having Hauptschulabschluss as their highest level of school qualification can be considered to be a marker of educational poverty, but not for men born before 1966. This suggests that, as might be expected given what we know about education as a positional good (Hirsch 1976, see Sect. 2.1) and qualifications inflation (Dore 1976, see Sect. 2.1), the value of Hauptschulabschluss decreased over time because of the general increase in levels of school qualifications. As for the difference between men and women, this may be linked to the increase in women’s labour market participation: for women born earlier, given the expectation that they would raise a family, it is possible that they did not see the need to attempt to obtain a post-school qualification if they could expect this to be difficult given their low level of school qualification.

While it was useful to draw on theoretical work undertaken in the field of material poverty in conceptualising educational poverty, it seems likely that the relevance is limited when it comes to policy implications. The means of tackling poverty are likely to differ between the two fields (even though the two types of poverty may well share some causes). For example, I noted above that material poverty can in principle be alleviated by transferring money to the individuals affected, but this is not the case straightforwardly for educational poverty. While it is possible to create opportunities for gaining qualifications at any stage in an individual’s life, this alone does not mean that they will be taken up.

With this paper, I have intended to contribute to the existing work on educational poverty and thus to encourage further empirical research drawing on this concept. Any such research ought to take account of the relative nature of educational poverty, as I have demonstrated.

Availability of data and material

Data were supplied by the LIfBi.

Notes

I refer to formal qualifications because they are the main focus in this paper. Similar arguments would apply to competences not measured by certificates.

In addition to such substantive changes in circumstances, an individual’s official poverty status varies with the setting of the poverty line, so that even without a change in circumstances, someone may be defined as being poor when previously they were not, and vice versa. But this is an artefact arising from decisions which may be politically motivated and which do not necessarily mirror closely the experience of the individuals concerned.

A sudden loss of the value of qualifications can, of course, occur following emigration to a country where one’s qualifications are not recognised, or, for qualifications obtained in the UK, as a result of Brexit and the accompanying loss of EU-wide automatic recognition of professional qualifications obtained in other member states.

Townsend gives a simple example in discussing tea: “Tea is nutritionally worthless, but in some countries is generally accepted as a ‘necessity of life’. For many people in these countries drinking tea has been a life-long custom and is psychologically essential. And the fact that friends and neighbours expect to be offered a cup of tea (or the equivalent) when they visit helps to make it socially necessary as well: a small contribution is made towards maintaining the threads of social relationships.” (p. 50).

Referring to this dependence of the definition on the country under study might of course be seen as describing relative rather than absolute poverty.

This paper is part of a larger project with a common dataset. Unlike those in the present paper, some of the other analyses draw on parents’ status which is why cases with missing data on these measures were excluded. However, the analyses presented in this paper were repeated with a slightly larger dataset (n = 17,107) which only excluded cases if data were missing on respondents’ education, and the results were essentially the same.

It will be interesting to analyse this relationship using the NEPS adolescents and students data once they have been collected for long enough for most respondents to have potentially reached the outcomes of interest.

Clearly, this does not apply to competences which can—appropriate tests permitting—easily be measured on an interval scale.

This brief description is a simplification of the German system with its 16 federal states, all of which have their own educational systems, though with common elements across all 16 states.

Using years of education instead of certificates would lead to similar problems for much the same reasons, as discussed in the previous section.

Nothing hinges on the choice of software package since I have no reason to expect different findings were I to use an alternative package, given the structure of my data.

No ordering is implied by the choice of the 1 and 0 labels, these are merely following convention.

Strictly speaking, quasi-sufficiency is being assessed, since we will not often, in large n studies, find a relation of perfect sufficiency. What Ragin’s use of quasi-sufficiency captures is something like: the combination of conditions is sufficient to raise the proportion gaining the outcome above the chosen threshold. Quasi-sufficiency therefore can be used to assess how closely the truth table data reflect perfect sufficiency.

The truth table suggests that there are no cases with no school qualification who go on to obtain a post-school qualification (see the four consistency values of zero). While it is plausible that this would be very difficult for them, this is likely to be partly an artefact arising from the use in the NEPS data of the CASMIN classification of qualifications which, in constructing the relevant derived variables, assumes that anyone with a vocational qualification has previously obtained the required school qualification, correcting any (presumed) mistakes in a process of data-cleaning and variable construction (Zielonka and Pelz 2015).

The figure basically gives the proportion of cases with the outcome that are accounted for by this path.

References

Allmendinger, J.: Bildungsarmut: Zur Verschränkung von Bildungs- und Sozialpolitik. Soziale Welt 50(1), 35–50 (1999)

Berg-Schlosser, D.: Calibrating and aggregating multi-dimensional concepts with fuzzy sets: “Human Development” and the Quality of Democracy. Australas. Mark. J. 26(4), 350–357 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2018.10.008

Blossfeld, H.-P., Roßbach, H.-G. (eds.): Education as a Lifelong Process. The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), 2 ed. Springer VS, Wiesbaden (2019).

Blossfeld, P.N., Carstensen, C.H., von Maurice, J.: Zertifikatsarmut gleich Kompetenzarmut? Zum Analysepotential des Nationalen Bildungspanels bei Fragen der Bildungsarmut. In: Quenzel, G., Hurrelmann, K. (eds.) Handbuch Bildungsarmut, pp. 467–489. Springer, Wiesbaden (2019)

Cooper, B.: Applying Ragin's Crisp and Fuzzy Set QCA to Large Datasets: Social Class and Educational Achievement in the National Child Development Study. Sociological Research Online 10(2), http://www.socresonline.org.uk/10/12/cooper.html (2005).

Cronqvist, L. (2003): Presentation of TOSMANA. Paper presented at the COMPASSS Launching Conference, Louvain-La-Neuve and Leuven, 14/07/2006

Cronqvist, L., Berg-Schlosser, D.: Multi-value QCA (mvQCA). In: Rihoux, B., Ragin, C.C. (eds.) Configurational comparative methods. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and related techniques. pp. 69–86. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (2009).

Dore, R.: The diploma disease. Education, qualification and development. Allen & Unwin, London (1976).

Glaesser, J., Cooper, B.: Selectivity and flexibility in the German Secondary School System: A configurational analysis of recent data from the German Socio-Economic Panel. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 27(5), 570–585 (2011)

Greckhamer, T., Misangyi, V.F., Fiss, P.C.: Chapter 3 The Two QCAs: From a Small-N to a Large-N Set Theoretic Approach. In: Fiss, P.C., Cambré, B., Marx, A. (eds.) Configurational Theory and Methods in Organizational Research, vol. 38. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, pp. 49–75. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, (2013)

Hirsch, F.: Social limits to growth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1976)

Lohmann, H., Ferger, F.: Educational Poverty in a Comparative Perspective: Theoretical and Empirical Implications. In: SFB 882 Working Paper Series, No. 26. DFG Research Center (SFB) 882 From Heterogeneities to Inequalities. Bielefeld, (2014).

Quenzel, G., Hurrelmann, K. (eds.): Handbuch Bildungsarmut. Springer, Wiesbaden (2019a)

Quenzel, G., Hurrelmann, K.: Ursachen und Folgen von Bildungsarmut. In: Quenzel, G., Hurrelmann, K. (eds.) Handbuch Bildungsarmut, pp. 3–25. Springer, Wiesbaden (2019b)

Ragin, C.C.: The Comparative Method. Moving beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London (1987)

Ragin, C.C.: Fuzzy-Set Social Science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London (2000)

Ragin, C.C.: The Limitations of Net-Effects Thinking. In: Rihoux, B., Grimm, H. (eds.) Innovative Comparative Methods for Policy analysis, pp. 13–41. Springer, New York (2006)

Ragin, C.C.: Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2008)

Ragin, C.C., Fiss, P.C.: Intersectional inequality. Race, class, test scores, and poverty. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2017)

Rihoux, B.: Qualitative Comparative Analysis: Discovering Core Combinations of Conditions in Political Decision Making. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press, (2020)

Rihoux, B., Ragin, C.C.: Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks (2009)

Sen, A.: Poor, relatively speaking. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 35(2), 153–169 (1983)

Solga, H.: Bildungsarmut und Ausbildungslosigkeit in der Bildungs- und Wissensgesellschaft. In: Becker, R. (ed.) Lehrbuch der Bildungssoziologie, pp. 411–448. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden (2011)

Thiem, A.: QCApro: Advanced Functionality for Performing and Evaluating Qualitative Comparative Analysis. R Package Version 1.1–2. http://www.alrik-thiem.net/software/. http://cran.r-project.org/package=QCApro (2018)

Thurow, L.C.: Education and Economic Equality. Power Ideol. Education 28, 325–335 (1977)

Townsend, P.: Poverty in the United Kingdom. A survey of househould resources and standards of living. Penguin, Harmondsworth (1979)

Zielonka, M., Pelz, S.: NEPS Technical Report: Implementation of the ISCED-97, CASMIN and Years of Education Classification Schemes in SUF Starting Cohort 6. In. Leibnitz Institute for Educational Trajectories, Bamberg, (2015)

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Barry Cooper for his extremely helpful thoughts and comments on this paper. I also thank the LIfBi for providing the NEPS dataset.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No external funding was received for the work reported in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glaesser, J. Relative educational poverty: conceptual and empirical issues. Qual Quant 56, 2803–2820 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01226-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01226-3