Abstract

The purpose of this study is to test whether groups with different cultural cognition orientations construct different stories about the same policy issue given the same information. We employed a focus group methodology to assemble participants with similar cultural dispositions and used the Narrative Policy Framework to examine the policy narratives that groups form about campaign finance. Our analyses indicate that the stories these homogeneous cultural groups tell associate political process concerns related to campaign finance to their core cultural values. Even when provided with the same information, the stories that the groups produced varied along theoretically consistent cultural dimensions. Our findings show the narrative cores displayed similar attribution of the problem to intentional human action; however we observed variation in the manner in which certain characters were assigned blame, and significant differences in the density of several of the narrative networks. We found that differences in presence of victims emerged along the grid dimension of cultural cognition with egalitarian narratives cores possessing victims, whereas hierarchist narratives did not. A difference that emerged along the group dimension of cultural cognition was the core narrative of individualist groups generated policy solutions, while communitarian narrative cores did not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) posits narrative as a fundamental driver of policy change, policy outcomes, and policy processes. While NPF scholars have made inroads in explaining narrative’s role in shaping these important public policy dependent variables (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011, 2013, 2018a; McBeth et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2014), there is still a considerable amount to be learned about the processes by which policy narratives are formed. The research presented here speaks to this gap by exploring the formative processes whereby cultural orientations impact the story that groups generate about campaign finance reform, a low salience policy issue. To accomplish this task, we analyze transcripts of four focus groups conducted in the summer of 2011. Each one of the four groups were designed to be culturally homogeneous and distinct. A moderator initiated a discussion of the current system of campaign finance and allowed the group to develop their own explanation of its functions, strengths, and weaknesses. After this explanation emerged, the moderator presented the group with an information packet containing facts about campaign financing in the United States, and a specific proposal to reform the existing campaign finance system. Given that the group was prescreened for interest in campaign finance, but also knew little about the information presented to them, we hypothesized that each group would use narratives rooted in their cultural orientations to make sense of campaign finance reform. Our hypothesis was confirmed. Indeed, each group formed a culturally specific policy narrative about campaign finance reform that was distinct from the other groups. In what follows, we first provide some background information about the development of United States campaign finance reform policy. Next, we describe the theories that drove our research design, followed by a discussion of the data and methods. Finally, we provide an analysis of the distinct narratives generated by each culturally specific focus group. We focus on the observed variation between the presence or absence of particular narrative elements and the manner in which these elements are connected along lines consistent with cultural cognition theory (Kahan 2012).

2 Campaign finance reform: a brief review

Ever since currency encountered democratic governance in the United States, funding political campaigns has been a troublesome aspect of the democratic process. Louise Overacker, an early scholar of United States money and politics, observed that the “…financing of elections in a democracy is a problem of…increasing concern” (1932, p. vii). Since then, the United States campaign finance regulatory apparatus has come to reflect that concern. The Mugwump crusade against government corruption in the post-Civil War era and the Progressive agenda at the turn of the 20th Century did much to instill a culture of regulation (La Raja 2008). Rooted in anti-partisan sentiment that celebrated the ability of the individual to make objective and rational decisions, Progressive-era reforms generated a complicated fabric of regulation including civil service reforms, ballot-design revision, financial disclosure requirements, and both expenditure and contribution limits, in various combinations across the states by 1928 (La Raja 2008). But it was not until recently that the greatest changes in the national structure of campaign finance developed.

The Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) of 1971 and subsequent amendments codified many national regulations governing individuals, parties, and political action committees (PACs). It also established the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to oversee campaign spending and the newly created presidential matching fund program. Some of the provisions of FECA were overturned in Buckley v. Valeo, illuminating an ongoing tension between popular will manifest in the legislature and the constitutionality of that will defined by the Supreme Court. It wasn’t until 2002 that Congress would follow up FECA with major campaign finance reform.

The Bipartisan Campaign Finance Act of 2002 (BCRA), also known as McCain-Feingold, raised the individual contribution limits but focused primarily on soft money, defined as those “funds given by corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals” and used by parties for non-electioneering functions such as get out the vote efforts and other party-building activities (Smith et al. 2010, pp. 14–15). BCRA served to “(1) ban soft money fundraising and spending by political parties and (2) prohibited the use of soft money by any organization and on advertisements 30 days before a primary and 60 days before a general election in which a federal candidate was on the ballot” (La Raja 2008, pp. 106–107).

In 2010, the Supreme Court stepped in, and in a close 5–4 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission held that the limits placed on corporations and unions were unconstitutional. Specifically, these entities had the same right as individuals to make independent campaign expenditures. In practice, this ruling meant that corporations and unions could spend as much as they wanted to in their efforts to shape election outcomes. Of course, the average American citizen is unaware of most, if not all, of this.

Citizens in the United States are quick to voice their dissatisfaction with the role of money in politics (e.g. Jorgensen et al. 2018; Shaw and Ragland 2000) and are quick to point out that they endorse reform of the political system (e.g., Pew Research Center 2018; Jorgensen et al. 2018; La Raja and Schaffner 2011). Despite this trend, campaign finance is a low salience issue and Americans—even citizens concerned about it—know little about campaign finance policy (Jorgensen et al. 2018). Thus, we can expect that most Americans would not have a detailed grasp of campaign finance law (Milyo and Primo 2017), which makes this issue ideal for conducting research about the narratives groups form when their members encounter complex information environments that they have little knowledge of prior to entering the environment.

3 Groups and their stories: political culture, cultural cognition, and the narrative policy framework

Sustained social interactions—and the lasting effects wrought about by those interactions—are what we might mean when we invoke the idea of culture. The study of political culture is concerned with the lasting and systematic effects of that culture on phenomena distinctly political—how we organize, decide, govern, and the like. With a concept so vast, it should not be surprising that no single monolithic academic approach to political cultural has emerged. Below we briefly discuss several of the scholarly approaches to political culture and why we have chosen cultural cognition as a way to empirically measure culture in our research. We then detail the four cultural orientations of cultural cognition. Finally, we describe the Narrative Policy Framework as a way to measure the ways in which different cultural groups tell their stories.

3.1 Political culture

The concept of political culture has been under near continuous development since its introduction by Almond (1956). Perhaps most influential in this development is the seminal study by Almond and Verba (1963) where the researchers developed a tripartite categorization scheme of subject culture, parochial culture, and participant culture. Other approaches have since also garnered considerable attention. For example, Elazar’s (1984) three-part characterization of US political culture as moralistic, individualistic, or traditionalist has inspired many studies such as those examining public policy (e.g., Morgan and Watson 1991) and electoral outcomes (e.g., Fisher 2016a, b), to note but a few. Another macro-approach to the study of culture was pioneered by Geert Hofstede, who developed his cultural dimensions framework based on four different cultural dimensions, which facilitated a great deal of research in cross-cultural comparison, especially in the fields of management and the study of organizations (e.g., Hofstede 2003). As seen above, political culture theorizing has given birth to a variety of ways to conceptualize or name dimensions of political culture. Here we have selected the cultural cognition (e.g., Kahan et al. 2011) approach for assessing political culture, a derivative of Cultural Theory (Thompson et al. 1990), which has shown itself to scale well from macro-levels of analysis (e.g., national) all the way down to individuals (see Swedlow 2011 for an overview), which serves our purposes well in attempting to understand variation in narratives across culturally homogenous groups of individuals.

3.2 Cultural cognition

Recognizing that individuals make sense of the world through the understandings they share with their communities, anthropologist Mary Douglas and political scientist Aaron Wildavsky began working on the cultural theory of risk in the 1970s and 1980s (e.g., Douglas 1974; Douglas and Wildavksy 1982). This early work eventually culminated in a formal approach to the study of culture more generally, titled Cultural Theory (CT) (Thompson et al. 1990). Subsequent research has built on this classic variant of CT and has offered insights into decision-making (e.g., Chai et al. 2011), public preferences (e.g., Jones 2011), and institutions (Lockhart 2011), to cite just a few areas of inquiry (see Mamadouh 1999; Swedlow 2011, 2014). At the heart of CT are two dimensions that allow researchers to sort individuals by cultural orientation. CT theorizes that individuals orient themselves using preferences for group belonging (Group) and the extent to which groups are allowed or expected to prescribe behaviors (Grid). This research relies upon a variant of CT known as cultural cognition.

Cultural cognition (CC), like CT, measures individual beliefs on the aforementioned dimensions: hierarchy-egalitarianism measures grid, while individualism-communitarianism measures group (Kahan et al. 2011, p. 8). This produces four ways of life: hierarchical-individualism (HI), hierarchical-communitarianism (HC), egalitarian-individualism (EI), and egalitarian-communitarianism EC, (also referred to as egalitarian solidarism, see Fig. 1) (Kahan et al. 2011, p. 9).

Each quadrant is theorized to capture latent cultural predispositions of individuals who view the world through a specific filter that works to produce systematic cognitive biases. These biases influence how people process new information. Confirmation bias is a process whereby individuals are predisposed to accept information that affirms their priors (i.e. culture), while disconfirmation bias predisposes individuals to reject information or stimuli that does not (e.g., Lodge and Taber 2007). Together, these processes are understood as identity protective cognition (Kahan et al. 2007, 2011) and its influence over how incoming information is processed is substantial, particularly as it relates to risk. For example, hierarchical-communitarians view gun control as high threat, egalitarian-communitarians do not; hierarchical-communitarians find abortions a high threat, individualist-communitarians do not (see Kahan 2012).

Kahan (2012) describes the hierarchical-individualist who values structure but also feels less constrained by groups:

Think of the iconic American cowboy, the “Marlboro Man”: He bridles at outside interference with the operation of his ranch, yet still exerts authority over a small community whose members—from ranch hands, to wives, to sons and daughters—all occupy scripted, hierarchical roles (p. 735).

Similarly, hierarchical-communitarians value hierarchy but also place value on group membership. Individuals in the military or members of a rules-based religion are likely to end up in this quadrant. Egalitarian-communitarians recoil from hierarchy and prefer to see themselves as part of a larger community. Many environmentalists fall into this category. Egalitarian-individualists fall in the bottom left quadrant and favor equality, having distaste for hierarchies, and favor markets and other mechanisms that allow individuals to compete fairly. Each of these groups views the world differently and can take the exact same information and come to quite different—indeed, polar opposite—conclusions about risk (Kahan et al. 2011).

Cultural worldview has an impact on how individuals understand public policy problems, and the solutions they find acceptable (Zanocco and Jones 2018). When investigating the power of scientific research to convince laypersons, Kahan et al. (2011) found that participants’ acceptance of an academic as an “expert” varied in accordance with their grid and group scores. Additionally, Kahan et al. (2007) found that neither race nor gender influenced risk assessment alone but acted “in conjunction with distinctive worldviews that themselves feature either gender or race differentiation or both in social roles involving putatively dangerous activities” (Kahan et al. 2007, p. 3). Such studies demonstrate that bias in assessing scientific evidence can be explained, partially, by cultural cognitive commitments.

Kahan et al. (2010) use CC to explain opposition or support for outpatient commitment laws (OCLs). In this study, the researchers test CC hypotheses applied to a policy dispute where expert consensus is not present, as OCLs have only recently emerged as a policy controversy. Kahan et al. (2010a) found that higher scores on individualism were associated with less support for OCLs while increased hierarchy was associated with stronger support for OCLs.

Kahan et al.’s (2010) study of the vaccination of young women for human papilloma virus (HPV) found that “biased assimilation” in addition to “source credibility” (Kahan et al. 2010b) influenced the stance taken toward the desirability of vaccination. They discovered that individuals who were more individualistic and hierarchical were more concerned about the negative consequences of the vaccine, while egalitarian and communitarian individuals were less concerned (Kahan et al. 2010b, p. 511).

Furthering this avenue of exploration into public policy areas lacking expert scientific consensus on the desirability of particular policy solutions, the work of Kahan et al. (2011) cited above is relevant to questions of campaign finance reform, as no scientific consensus on the desirability of one campaign financing system over another exists. Their work suggests that cultural differences are likely to drive the types of reform initiatives that individuals find desirable. This research explores how individuals utilize narratives to come to those varying conclusions. To do so, we leverage the NPF.

3.3 Narrative policy framework

Narratives are the primary means by which human beings make sense of the world (e.g., Jones 2018; Shanahan et al. 2018b; White 1981, 1987). The NPF measures this sense-making through narrative content and form. Narrative form can be effectively conceived as a constellation of structural elements which are likely to be featured in all policy narratives, such as the kind of narrative likely to develop in a discussion of campaign finance reform. The NPF posits four main narrative elements that constitute form: characters (e.g., a villain who causes a harm; a victim who is harmed; and a hero whose action helps the victim and stops the villain); the moral of the story, or the policy solution (what the hero does to address the harm); the setting of the tale (where the narrative takes place); and the plot (which lays out the interactions over time between characters and the setting). Within the NPF, these elements are fundamental facets of narrative that can be identified, quantified, and compared across policy areas (Jones 2018; Shanahan et al. 2018b).

Narrative content, on the other hand, may be quite specific to the policy area in question. For example, narratives about tariffs on international trade may have little in common with policy narratives about manned space exploration. Systemic understandings of narrative content can thus be difficult (referred to as the problem of narrative relativity within the NPF—see Jones et al. 2014). To attempt to produce generalizable findings relative to narrative content, the NPF argues that one must understand the belief systems individuals and groups use to help them attach meaning to the varied content of narratives (characters, symbols, evidence, etc.). For example, Hillary Clinton, as a character within a policy narrative, is likely to generate quite predictable—and opposite—emotional reactions from individuals belonging to liberal and conservative networks or groups in the United States. Beliefs are thus the “glue” that often hold groups and coalitions together (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993) and have been measured in past NPF studies to understand policy differences (e.g., McBeth et al. 2005).

Through narratives individuals are able to emphasize certain aspects of reality while drawing attention away from other facets of reality deemed to be of lessor import (Gilovich 1991; Shanahan et al. 2018c). In doing so, narratives ascribe differential value and assert relationships, they function to convey right and wrong, virtue and vice, and to sculpt contours of group membership so individuals can be placed in epistemic communities. Narratives also employ particular strategies, such as causal mechanisms in their quest to identify a particular group, phenomenon, or institution, that is responsible for the existence or emergence of a particular public problem (Shanahan et al. 2018b). This process is fundamentally social, and it means that narrative transmits culture, as maxims, rules-of-thumb, and common sense (as well as more technical information) between individuals. Thus, it is posited that while individuals do make sense of the world on their own, when they are confronted with new or complex information, individuals likely turn to their group culture to narratively structure that information, assess threats, and make sense of the world more generally. In this research, Cultural cognition, operationalized as a subset of the NPF belief system classification, is theorized to drive said story creation.

4 Data and methods

In this research, the unit of analysis is the group narrative produced by individual actors within a culturally congruent focus group. Four groups were utilized, as defined by cultural cognition. Of primary concern was the way in which a group’s culture structures narrative formation in low salience, low information policy areas. Each group was primed for discussion by prompting each member to describe the current state of the United States of America, in a single word (uncertain, terrible, etc.). The moderator then asked individuals to expand upon the reasoning behind their word choice. This opened the discussion on the participants’ terms and established the focus group as a place where the moderator plays a reserved role. After a brief conversation, the moderator presented information about United States campaign finance policy, an issue with low salience and that most Americans know very little about. Narrative theory and previous research (Song et al. 2014) suggest that individuals will rely on their familiar groups to make sense of the information through storytelling. Drawing from the extant literature, we seek to answer these research questions:

RQ1: Do groups composed of individuals with different CC worldviews form narratives distinct from one another when asked about campaign finance reform?

RQ2: Does the provision of additional information with regard to campaign finance reform result in changes to the structure of narratives produced in focus groups with homogenous CC worldviews?

The subsequent sections address the research design utilized in this study.

4.1 Data

To address our research questions, we conducted four focus groups in Oklahoma City in June of 2011. Each focus group consisted of pre-screened participants that were paid seventy-five dollars for their services. In April of 2011 a pool of voluntary respondents was screened for one of the four focus groups based on specific criteria. First, potential participants were screened for a minimal interest in campaign finance reform.Footnote 1 The logic behind this criterion was that a minimal interest level would make participants more likely to engage and think seriously about the issue in the focus group setting. To determine the cultural affinities of participants, each was asked to respond to two batteries of statements, where each represents one dimension of cultural cognition: hierarchy—egalitarianism (i.e., grid) and individualism—communitarianism (i.e., group), respectively. Each battery consisted of six statements typical of CC studies (e.g., Kahan et al. 2011, p. 27) where each statement was a simple dichotomous agree or disagree, coded one or zero, respectively. Responses were then summed for each dimension.Footnote 2 Intersecting the two orthogonal dimensions of hierarchy—egalitarianism and individualism—communitarianism produces four distinct cultural quadrants: hierarchical-communitarian, hierarchical-individualist, egalitarian-communitarian, and egalitarian-individualist. Since we are interested in evaluating the effect of CC on sense-making narratives we wanted participants that were clearly in one quadrant and not individuals from the center of the distributions. We selected 10 participants for each group that scored in the top and bottom quartiles for each of the two dimensions.Footnote 3 The logic was that these individuals, when placed in groups, would produce more distinguishable cultural narratives than individuals with more centrist responses. This process produced four focus groups with 10 non-centrist cultural types in each (see Appendix 1 for instrument). Each focus group ran for approximately 1½ hours, was video recorded, and professionally transcribed.Footnote 4

The construction of each group reflected our desire for an environment that felt culturally friendly for each participant. Once in this safe environment, participants were presented with campaign finance reform information. As Morgan observes, “what makes the discussion in focus groups more than the sum of separate individual interviews is the fact that the participants query each other and explain themselves to each other” (1996, p. 139). Ryfe observes that participants “may argue, debate, or talk, but the clear pattern is that they prefer to tell stories” (2006, p. 73). As Black notes, within groups, storytelling begets dialogue, which likely helps individuals within the group overcome any interpersonal differences that exist (Black 2008). Thus, group dynamics make a focus group an optimal setting to observe the formation of sense-making narratives. Our expectation was that an organic sense-making process would ensue whereby the group would form a narrative situating the newly acquired information within their common culture. Given our expectations, our methodological concerns required a specific moderating style.

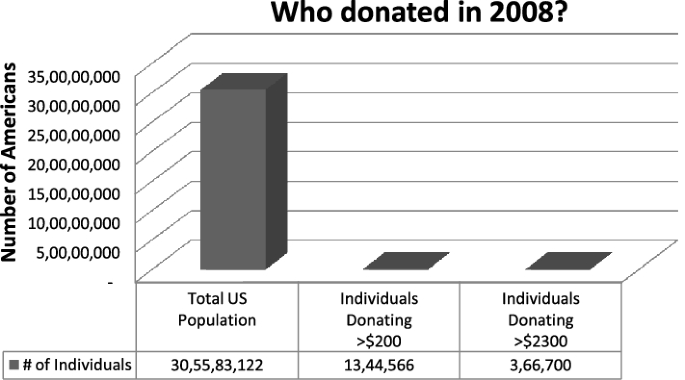

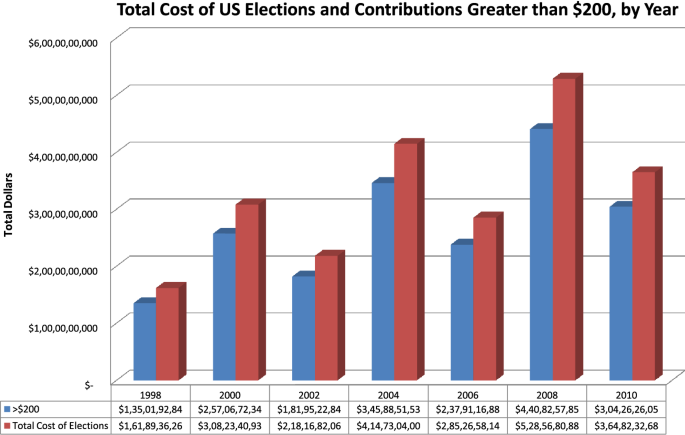

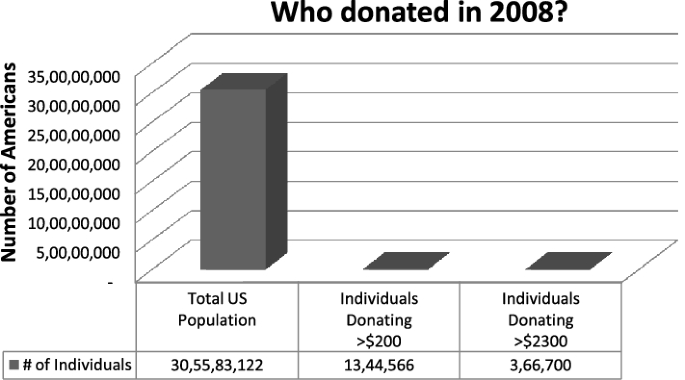

Morgan (1996) describes two basic approaches to moderating focus groups: a more structured environment imposes the researcher’s interest while less structure allows the group to pursue its own interests (p. 145). Ryfe finds that in a deliberative setting the “open and relaxed approach of facilitation is the most likely to engender more storytelling on the part of participants” (2006, p. 75). Our aim was the latter and the moderator for each group was given instructions to provide as little guidance as possible. Instead, the moderator asked a limited set of pre-scripted questions and introduced the information on campaign finance reform to the participants (see Appendix 2).Footnote 5 This information included basic facts about campaign finance law in the United States, statistics on who gives to campaigns, and also described a proposed government-sponsored overhaul of the campaign finance system aimed at reducing the impact of private money on elections. Outside of those functions, the moderator was to let the participants do “the hard work of establishing who they are in relation to others” (2006 p. 75). This meant that the moderator did not convey the exact same information at the exact same time to each group (Table 1). As such, both network and traditional statistical measures are utilized to compare the group narratives prior to the introduction of information. Comparisons between pre- and post-information period are undertaken within group only, not across groups, and do not employ traditional statistical measures.

4.2 Methods

This study employs a deductive coding scheme to analyze narrative differences between the four focus groups. We rely on previous NPF codebooks to guide our coding of the transcripts (see Shanahan et al. 2018b, c). The texts were coded for characters (consisting of coding heroes, villains, and victims), policy solutions (moral of the story), and causal mechanismsFootnote 6 (Table 2).

In line with previous NPF research content coding strategies (e.g., Smith-Walter et al. 2016, 2018), two researchers coded the focus group transcripts at the paragraph level of analysis for the presence-absence (0 or 1) of each category with reliability tests for each coded item (Table 2). The coders achieved an acceptable level of reliability for each coding category.Footnote 7 The data were then analyzed in two ways to understand narrative differences between focus groups. First, the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test was conducted to understand statistical differences in narrative components (due to the ordinal nature of group membership). Variables found to exhibit statistically significant differences were then compared, group by group, to identify group differences. Because this research applies CC and NPF to campaign finance within focus groups for the first time, the researchers took a conservative approach to identifying relationships by choosing the Bonferroni correction to guard against Type I errors due to the large number of repeated hypotheses being tested. Second, a network analysis was conducted to understand the centrality, density, and core/periphery elements of narratives. Taken together, the results illuminate how groups constructed narratives before and after receiving information on campaign finance.Footnote 8

5 Results

In many respects, groups had similar opinions, such as being pessimistic about the state of the country and negative feelings towards government, but their narrative constructions differ when examining characters, policy solutions, and, to a certain extent, causal mechanisms, the building blocks of what constitutes a policy narrative (Shanahan et al. 2018a). Consistent with our expectations, a unique narrative emerged from each focus group.Footnote 9 We reveal our findings with a network analysis and more detailed node-level explorations of characters, plot, and causal mechanisms.

5.1 Pre-information narrative network comparison

We begin by comparing the narrative networks from the focus group discussion prior to the introduction of specific campaign finance information. Since we want to discover if different narratives emerge from the groups (RQ1) we deploy social network analysis (SNA) to map and compare the characteristics of the narrative generated by each CC focus group. The analyzed networks were generated using the affiliation command in UCINET 6 for Windows which transforms a two-mode dataset (rows representing coded text and columns representing narrative elements) into a 1-mode adjacency matrix where the value of each cell reflects the number of links between each narrative element and all other narrative elements using the sums of cross-products. Each node represents a narrative element (heroes, villains, victims, policy solutions, or causal mechanisms). Larger nodes indicate greater degree centrality of a node (narrative element) in the network. For instance, the hierarchical-individualist pre-information narrative network map identifies a private individual as a villain with 20 links. The node is larger than the node for money which has 2 links. Links between the nodes represent instances where an element co-occurred with another element (in one coded paragraph). The darker lines indicate a greater frequency of co-occurrence.

The density measure for each focus group’s narrative network was computed. Density is a measure that conveys the general level of connectivity between the nodes in the network and is calculated by dividing the total number of dyadic ties present in the network by the total number of all possible ties in the network (Yang et al. 2017, p. 58) (Table 3).

Prior to information dissemination by the moderator, we see egalitarian-communitarians have the densest network (19.1%), followed by the hierarchical-communitarians (15.9%). Hierarchical-communitarians and egalitarian-individualists demonstrate much lower narrative network density measures of 9.5% and 4.0% respectively. To discover whether the differences are statistically significant, we utilized the compare densities function (paired networks in UCINET 6) with 10,000 bootstrapped samples and found the hierarchical-communitarian network was significantly denser than the egalitarian-individualist network by 11.9% (Sig. 0.030 p < .05). Hierarchical-communitarian network density was significantly less dense then the egalitarian-communitarian one, by 9.7% (Sig. 0.045 p < .05). The egalitarian-individualist network was significantly less dense than both the hierarchical-communitarian and egalitarian-communitarian narrative network densities, the latter by 15.2% (Sig. 0.011 p < .05) (Table 4).

Density differences are important pieces of information for understanding how CC and the NPF combine to generate insights into narratives for at least two reasons. First, density may represent a cognitive foundation amenable for future information incorporation (more on this below). It is the contention of both the NPF’s model of individual cognition (see Shanahan et al. 2018b, c, pp. 179–183) and CC that existing beliefs and identity commitments impact the assimilation of new information, so understanding the embeddedness of relationships between existing narrative elements could be vital to anticipating the likely power of a particular narrative to persuade a given group. Second, the density of a narrative network may indicate a more cohesive story, with greater ties between narrative elements indicating connections between concepts, or at least the existence of more elements the audience can identify with. This may represent an approach to exploring narrativity, which is the notion that more complete stories are more persuasive (e.g., Crow and Berggren 2014).

If the density of the narrative networks varies between cultural groups, what might this mean for the study of narratives? We can begin by generating network maps for each of the groups. The network diagrams (Fig. 2) show that differences in density translate to “fuller” graphs for hierarchical-individualists and egalitarian-communitarians, as more nodes are connected than in networks assembled by hierarchical-communitarians or egalitarian-individualists.

In Fig. 2, the size of a node is directly related to the number of ties it has to other nodes (degree centrality). Darker lines indicate more instances of connection existing in the same paragraph. Larger nodes and darker lines help identify a distinction between network core and periphery. The core/periphery measurement identifies nodes which constitute a “community” with dense connections to other nodes and which have sparser connections with nodes not in their community (Rombach et al. 2014). The core was identified using the MINRES algorithm and the continuous function with 1000 iterations. The core is important for using SNA to analyze policy narratives because it brings to the forefront those narrative elements that are most frequently employed together while simultaneously illustrating the elements’ connectedness to the entire network. UCINET 6 determines the core measures for each node in the network by comparing its structure to an idealized core/periphery block where several nodes with direct and dense ties exist without ANY connections to other nodes in the network. If the network under investigation matches this model exactly, values for core nodes will equal 1.0, and nodes that demonstrate more “coreness” return values closer to 1.0 (Everett and Borgatti 2005). If we find that the four narrative cores contain different elements and links, we can consider that differences in CC may contribute to the structuring of narrative networks (Figs. 3, 4, 5).

Drawing on these diagrams, and the density, centrality, and core/periphery measures applied to the four pre-information narrative networks, we can easily identify the similarities and differences between the story structures.

5.1.1 Causal mechanisms

Previous studies have found many narratives use intentional causal mechanisms, as villains are highlighted as an entity to combat (Shanahan et al. 2014). Below are examples of how these mechanisms arose in the focus group narratives.

- 1.

Intentional policymakers might be accused of making policies to increase their personal wealth.

- 2.

Inadvertent the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 might be explained as having raised inflation.

- 3.

Mechanical a bad policy might be explained as resulting from an unthinking bureaucracy.

- 4.

Accidental fluctuations in the price of commodities due to the weather.

One interesting aspect revealed by the narrative network maps is that each group expressed that campaign finance was a problem caused by intentional action to accomplish desired goals. That this emerged from all groups may indicate an understanding that the system of campaign finance is a product of human construction, maintenance, and manipulation. Unlike harm caused by natural disasters (accidental cause), machines (mechanical) or carelessness (inadvertence), injury caused by the campaign finance system is seen by all as intentional. This lack of ambiguity renders “the problem” of campaign finance amenable to a policy solution (Stone 2012), which is supported by extant campaign finance literature (e.g., Jorgensen et al. 2018). It is also important to note the HI, EI, and EC narratives connect the network nodes Intentional Cause and Villain: Government in their network’s core. Government does not occupy this key role in the core of hierarchical-communitarians. Perhaps HC’s are simply more favorably disposed toward the federal government (by virtue of their high grid and high group scores) and thus unwilling to craft a story with government as a core villain.

The final element in the pre-information narrative network core shared by EC and EI groups is private individuals as victims.

EI: “Yeah, and then they’re taking it down on us regular folk, and bumpin’ up our property taxes, you know?”

EC: “But it’s just going to destroy a lot of middle-class families when you say, “Hey, you know, it’s illegal to have, you know, unions.” And we called our politicians and you’d think that they would listen to you. And I know we have republicans and democratic teachers that were calling and you know, and fireman and whatnot. And they absolutely said, “We don’t care. This is what the big money people want us to do. So, we’re just going to ignore your vote.”

With the use of “regular folk” and “middle-class families” both groups associate the intentional exercise of power by malevolent government (in the case of EC’s), businesses, and private individuals with harm done to average Americans. This construction, also manifesting along the grid-dimension, suggests egalitarians of both varieties generate more cohesive campaign finance stories prior to possessing policy-relevant information. This may be due to factors related to the universe of characters in these stories, and to these characters we now turn.

5.2 Characters

Coded character categories include heroes (government, private individuals, and advocacy groups), villains (government, private individuals, advocacy groups, business, and money) and victims (government, private individuals, rights, and business). Given the CC quadrants defined above, we would expect that focus groups situated on the individualist side, i.e., hierarchical-individualist and egalitarian-individualist, would cast heroes as private individuals, villains as government and advocacy groups, and victims as private individuals. Similarly, we would expect communitarian focus groups, i.e., hierarchical-communitarian and egalitarian-communitarian, would cast heroes as government and advocacy groups, villains, as private individuals, business, and money, and victims as government. However, the pre-information narratives generated by the four different groups failed to demonstrate any statistically significant differences between ANY heroes or victims (see Table 5). When we narrow our attention to the narrative core, we don’t find ANY heroes and only the aforementioned private individual as victim in EI and EC cores. These particular stories are driven by villains. Since the focus groups dealt with campaign finance law, and villains like government and corporations were key to building a story about the issue, it is not surprising that the HC group didn’t generate a more cohesive network; intentional causes require villains and the likely villains in campaign finance reform are manifestations of entities hierarchical-communitarians tend to admire.

5.2.1 Heroes

Heroes are those characters who are cast as those who will fix the problem. The complexity of identifying heroes as individuals or government lay in that an individual must work within the system to affect change. For example, one member of focus group 1 (HI) recognized citizens’ capacity to stand up and make a difference (individualism) but situated this individuality within the community of the tea party: “We’re grassroots, we’re not a big corporation, we’re just people wanting to make a change. And that seems like that would influence the whole corruption big money.” As the network maps show, while each cultural narrative identified heroes that could be situated on opposite ends of the Group continuum, no hero was central enough to the story of campaign finance to exist in the narrative core.

5.2.2 Victims

The victim is the character who suffers at the hands of the villain. The primary victims for campaign finance were the government and the private individual. For the members of the HI group, corporations play a role like that of individuals, valuing freedom and choice for them as well. “They made it sound like corporations, the people, who spend a lot of money in elections is a bad thing. But do we ever stop and think, why do we tax corporations? Corporations shouldn’t have to pay money…what you end up doing is you stifle growth.” As one HI member said, “…in the society where we’re basing our life on freedom and you start telling people what they should and shouldn’t do with their money, which can be a lot farther reaching than any of us realize.” The hierarchical-communitarian and egalitarian-communitarians victims tended to center on money’s threat to the public interest. “…whoever puts in the most money…they’re going to end up on Saturday Night Live…and that is going to influence the public, and then really in the long run their guy is going to get in, and I feel powerless when I hear that kind of thing.” As with heroes, no statistically significant differences in frequency of victims arose between the four groups.

5.2.3 Villains

Villains are the characters responsible for the problem and it is here the differences between the CC groups begin to acquire more resolution. Participants in the focus groups developed narratives that spent considerable time expounding on villains. Focusing on the government as villain across the entire network (not simply examining the core) by using the Kruskal–Wallis H test, we reject the null hypothesis of no difference between the groups (p = .036 < 0.05). Digging deeper, we see that only two groups’ use of government as villain were statistically significant. Applying the Mann–Whitney U test to the four pairs, we find that statistically significant differences are only found between hierarchical-communitarians and egalitarian-individualists (p = .009 < 0.01). The test also found that power as a villain (i.e., power corrupts) demonstrated a significant difference between groups (8.581, p = .035 < 0.05) at the p = 0.05 level, but the stricter p value of 0.01 required by the Bonferroni correction when comparing the four groups individually to one another, failed to identify a significant difference between them.Footnote 10 Concerning villains in the pre-information stage, Grid is the operative scale here, as the HI group demonstrated more instances (n = 29) than the EI group (n = 10) painting government as villain. The HI focused on bad-natured individuals in government, and not the system as a whole. “…the politician in office has such a tremendous advantage because they can squeeze to get the money. They know how to say, ‘yeah, we’ll talk about that after your donation.’” In contrast, when HC narratives did identify government as villain, it was because individuals in government were not acting in the public interest. “Well, right now they are not living up to the role because they are not solving issues before them and it’s very, very divisive. It’s very, very political. And so they are not performing the role that they have or should be doing.” These distinctions provide support for CC’s theory that HI’s, “Marlboro men” will be extremely critical of external forms of authority infringing on their own domains of organized social relations.

However, when we consult the narrative network map, we see that despite the lack of statistically significant differences demonstrated by the Kruskal–Wallis H and Mann–Whitney U tests, three of the four groups (HI, EI, and EC) identified the government as a villain in their network core. The coreness measure was 0.611 in HC narratives, 0.540 for EC, and 0.516 for EI. Recalling that the core measure is derived from comparing the matrix under investigation with an idealized core model (of 1.0), these values indicate that the coreness of these measures is not slight. The government as villain achieved a coreness score of only 0.287 in the HC narrative, which shows that the HC group tended not to blame government, supporting CC’s theoretical stance that HC’s will generally value structure and authority.

These findings indicate that all groups identify the problems arising in campaign finance as generated by intentional human action, and all core narratives, excluding hierarchical-communitarians, lay at least some of the blame at the feet of the government. We can see that a villain that is accessible via existing cultural cognitive understandings allows the formation of more cohesive stories absent additional information. Hierarchical-individualism opposes the imposition of federal government on their local forms of hierarchy, egalitarian-individualism resents what they see as government waste and incompetence demonstrated in the statements like, “I don’t understand why Congress people are receiving a paycheck, when they haven’t obviously passed our previous [sic], budget?” Egalitarian-communitarians, on the other hand, have a more complex relationship that seems to emphasize the intersection between politicians and business interests, as seen in this statement, “But you see it happen every single time a president comes in and then when he leaves office the company that gave him the most money, he becomes a consultant. Probably doesn’t show up but just, you know, to give a speech and he makes a million dollars a year for, you know, the next 20 years or whatever as a consultant, you know, to that organization that gave him all that money.”

To summarize the findings related to the relationship between characters and plot we could describe the initial formulation for HI’s narrative as “government as corrupt”, for EI’s “government as incompetent”, and for EC’s as “government as co-conspirator”. HC’s have no initial core, since they apparently unwilling demonize government, though they too recognize the problem as within human ability to control.

5.3 Policy actions or moral of the story

We operationalized the NPF’s moral of the story as policy actions. For example, a pro-government action solution was voiced in the EI narrative when it was stated that “The government that is there for the people, they should step in and say, ‘Hey, this person who can’t afford three hundred a month, should not be given thirteen thousand”; a con-government action solution would have expressed opposition to such a statement. A pro-collective action other than government policy solution called for people to work together in the sphere of civil society to address the issue of campaign finance. A statement made in the EC focus group is indicative this type of solution, “I mean, this makes sense to me because, you know, you do fundraisers and you might get 100 people somewhere and ya’ll donate $200.You do that all over the country and you can fund them like that.” While four policy actions were coded, none demonstrated statistically significant differences using the Kruskal–Wallis H test: statements indicating support for government action (.989 > p. 05) against government action (.131 > p. 05) as well as statements advocating/opposing non-governmental or collective action by citizens (.109 > p .05/.183 > p. 05). This result is, in a certain respect, not surprising since none of the focus groups identified any hero in the narrative core to undertake corrective action. It is important to note this changes when comparing the pre-information narratives to the post-information narratives.

5.4 Post-information narrative structure within focus group comparisons

Moving now to the post-information analysis, it is important to remind the reader that the comparisons that will be made for the remainder of the article contrast pre-information narrative structure with post-information structure within individual CC focus groups. The moderator encouraged groups to range fairly freely in their discussion, and thus information provided to individuals prior to presentation of policy relevant information on campaign finance and the Grants and Franklins project (a government-based campaign finance reform policy) was not identical. However, handouts provided to each participant were identical, and the moderator provided three similar hypothetical arguments, one in favor and two opposed to the Grants and Franklins project (see Appendix 2). Comparing the post-information network of any group with its pre-information network is a way to assess how the introduction of new information impacted the development of each CC narrative. We begin by discussing changes in overall network measures.

We see the network density for the EC group was significantly reduced by providing more information, while the other groups showed no significant change (see Table 6). This is surprising since the density of the EC narrative network was highest prior to receiving the policy relevant information. Why this group should display such a significant drop is an interesting question, and one that will be explored in more detail below (Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9).

5.5 Characters

5.5.1 Heroes

The post-information narratives feature heroes in the core of HI and EI groups. In both cases, the heroes were, as the group dimension of CC would suggest, private individuals.

FG1 (HI): “The thing that, the thing we most need to understand is our founding fathers had a reason why they set up everything the way they set out to do and really quite brilliantly… But they also allowed us to spend whatever money, each person, each corporation wanted to at that time because that’s another way to make…almost like the three different branches of government, how they all work together. So you’re not just having the voting public, whether it’s a ignorant vote or whatever making their vote based upon whose pretty or who says the right thing. You got some people that if you got money, not very often do you get because it’s lucky. You get it because you got some kind of intelligence and that helps guide that somewhat.

FG3 (EI): Okay, but to me, what was good about that is, he was out among the people. Had been for a long time, and reflected a most of the state. I’m not saying everyone, I’m not even saying me, but a huge portion of our state. Without massive corporations backing him. Like one corporation getting him in. And if somehow that could play a part on a national level, where, your guy reflected the majority of the people, and somehow those people contributed, or voted, where who actually got in reflected us, not just one corporation, that’s ideal.

The private individual is employed differently, with the HI narrative equating smart individuals with rich individuals and portraying their contributions as a check on ignorant voters. The private individual, for the EI, is a person who works in the system for the good of the majority. This provides support for using CC to understand narrative differences, as both focus on the individual as an agent of positive change. The HI narrative is animated by the idea that an individual success in the economy should translate into greater influence in selecting national leaders, via campaign donations. EI stories do not focus on the distinction between intelligent and ignorant participants in the political process, but on the elected individual actually representing the will of the majority, while eschewing the unequal influence of concentrated economic power. These changes in narrative could be explained by the difference in grid influencing the nature of the hero employed in high- or low-grid worldviews and the high- or low-group aspect influencing whether a hero even enters the core narrative.

5.5.2 Victims

No victims were found in the narrative core of any group in the post-information portion of the focus group. The EI and EC core didn’t carry the private individual as victim over from their pre-information core. It is unclear what this might mean, but it may be that moving from the pre-information stage where the dialogue was conditioned more so by the influence of the variation in CC worldviews toward a discussion of a specific policy proposal sharpened the focus to groups that were unlikely to be viewed charitably by egalitarians.

5.5.3 Villains

The post-information portion of the focus group lead to a substantial change in the villains found in the narrative cores of each of the four groups. The hierarchical-communitarian narrative core retained government as a villain, but it was less of a core node than the new villain, private individuals. The crux of this villain was a direct response to the Grants and Franklin project’s call for the first $50 of federal taxes paid by each voting-age citizen to be transformed into a “democracy voucher” that individuals could direct to the politician(s) of their choice or elect to have it spent on voting infrastructure if they did not approve of any candidate.

FG1 (HI): Overall I don’t see a clear connection between, you know, campaign finance and how politicians get to Washington to the problems that we have because you know, whether a politician, you know, got there on a string bean budget or Kennedy type budget, if they’re corrupt, they’re corrupt. And they reflect the people in their district. So they’re [sic] the people in their district are freedom loving and gun totting or whether they are in the North and like to drink their tea with their pinkies up. The congressmen are going to reflect the values and the morals of their constituents and…

The HI narrative emphasizes that the major problem is that individuals are likely to take advantage of the system and many of the citizens are generally flawed. Again, CC helps to explain this emergence, since many of the reasons the HI group opposes the initiative relates to the need to check the excesses of democracy.

The rise of a new villain also occurs in the narrative core of the hierarchical-communitarians. This villain emerged from the detail in the Grants and Franklin proposal that allowed politicians to opt-out of the system and raise their money from private donations. This generated a consensus that businesses would oppose the system and that public finance couldn’t overcome corporate money without additional restrictions on corporate behavior.

FG2 (HC): But, these big corporations like Halliburton, that get all the government contracts have got to know that there’s millions and millions of dollars for campaign funding. And, if they just said, “Stop, no more, and if we catch you doing it, here is the penalty.”

This call is also in keeping with what CC would predict from hierarchical-communitarians, the call for public authorities to establish rules and regulations that would advance the public good and bring order to the process.

The Egalitarian-Individualist (FG3) narrative core also featured a new villain post-information: the private individual. This villain was, as in the hierarchical-communitarian core narrative, the ignorant voter.

FG3 (EI): But it just comes back to that same whole ignorance thing, that if people don’t know, and then they’re bombarded with this message, and how many of us really, when we have this coverage? I know I did. I’m sorry, I do the research on the candidates, I do the research on the bills, cause’ I’m around to care. I don’t want it to just be a vote. You know? I don’t want to be ashamed. Cause I know what I voted for. At the end of the day, it comes back and I voted for something I really didn’t stand for or believe in, so I mean, I know that I’m going to know what I vote for. How many of the average American’s that vote will?

This seems to indicate that individualists may have reacted to the plan to use public power to redistribute resources to level the playing field in campaign finance by casting doubt on their fellow citizens to wisely exercise this power. The egalitarian-communitarian narrative core did not add any new villains in the post-information stage.

5.6 Policy actions or moral of the story

Neither egalitarian-communitarian nor hierarchical-communitarian core narratives contained policy solutions. However, both hierarchical- and egalitarian-individualist core narratives employed a moral to the story. The solution preferred by the HI narrative was one that was promoting opposition to government action, the Grants and Franklin project specifically. This component relied on a distrust of the government and its power over individuals.

FG1 (HI): “This just seems un-American. It just doesn’t seem like it would be in a free market society. I just don’t see it working.”

The egalitarian-individualist core narrative, instead of opposing government action, proposes that collective action outside of government proper can correct some of the weaknesses of the current campaign finance system and its impact on contemporary politics.

FG3 (EI): And there’s a lot of government responsible for that. So, as for Obama being the problem. It’s years, and accumulation of years and years and years of being let down and the people, all of us, relying on the government, instead of being the government.

The use of network mapping and core and periphery measures provided evidence that each group’s core narrative was impacted by the provision of policy-relevant information and a specific policy proposal.

6 Discussion: cultural cognition and the NPF

In all, we find that cultural cognition as a lens can provide interesting insights into the influence of culture on the completeness and density of narratives generated in a low salience policy area. To explicitly answer our first research question, groups holding exclusive CC worldviews will generate different narratives from one another, though the differences are not always that stark and there certainly are facets of congruence across narratives. We have statistical evidence in the form of Mann–Whitney U tests from the pre-information analysis that finds significant differences between all forms of causal mechanisms (Mechanical, Intentional, Accidental, and Inadvertent), and that hierarchical-individualists are more likely to use government as a villain than groups with a different CC orientation.

In addition to those statistical differences, we also observe variation by looking at the network maps of the pre-information narratives. Coupled with the density measures, we see that the intentional cause occupies a position in each and every group’s narrative core. However, the H-C (FG2) narrative core isn’t comprised of any concept other than an intentional cause, and the H-I (FG1) adds only a villain in the form of Government. However, egalitarian groups (E-I and E-C) both displayed more developed networks of narrative components, with Private Individuals playing the victim in both groups’ narratives. E-C (FG4) had an even more robust group of villains, featuring Private Individuals and Business, in addition to Government. This multiplicity of villains may serve to bolster the “us versus them” dynamic which CC indicates animates this culture (Douglas and Wildavksy 1982). We also see that egalitarian pre-information narratives (E-I and E-C) both feature a victim, a feature lacking from the narrative core of either of the hierarchist groups (H-I and H-C). This seems to suggest that for those with a strong egalitarian culture, the identification and deployment of a victim is part of their narrative sense-making that differed from those with a strong individualist culture. We can therefore say, at least tentatively, that groups did produce narratives which differed in important ways from one another prior to the presentation of campaign finance information, including the Grants and Franklins Project reform policy solution.

Turning to our second research question, does the provision of additional information with regard to campaign finance reform result in changes to the structure of narratives produced in focus groups with homogenous CC worldviews? It seems that the answer is a tentative yes, as we saw that the core of each focus group did, in fact, change when new information was made available and the framing of the discussion became solidified in reaction to the Grants and Franklins proposal. However, in all cases, certain things did not change. For instance, in all pre- and post- groups, the problem was seen to be caused intentionally. In the HI, EI, and EC groups, government was portrayed as a victim pre- and post-information. While the HC group did NOT identify government as a core villain in either portion of the focus group. The EI narrative core featured private individuals as villains in both pre- and post-information, and so did the EC narrative core.

When looking for patterns in the changes in the narrative network core from pre- and post-information states, it is interesting to note that both narratives of the groups with a “low-group” worldview (HI and EI) moved from a less elaborate core to a more elaborate core, and that they shared four of the five elements in the post-information model. However, while the similarities are undeniable, the “coreness” of the elements, and the difference in the desired policy solution point to distinct narratives, though ones that share a familial resemblance. It is likely that this structure is one that emerges from opposition to the Grants and Franklins project, as government and private individuals were both villains and private individuals were also heroes. The distrust of government and other citizens may then be understood as an aversion to attempts to leverage public power to address social ills. Instead, the individualists try to deflect the use of governmental redistribution by decrying the loss of freedom of speech or by casting doubt on the ability of fellow citizens to effectively utilize the proposed resources.

Looking at the communitarian side of the coin (HC and EC) we see that the “high-group” cultures both fail to deploy a policy solution in their narrative core. It may be that the Grants and Franklins project was simply a culturally congenial solution they could endorse. If this was the case, the groups may have felt little need to focus on providing an alternative and could spend more time focusing on the reason to support the plan. This would explain the emergence of Business as a villain in the HC narratives.

The implications of our findings are several. Each group, presented with similar information about campaign finance policy in the United States, formed a narrative distinct from the others. These differences were discernable based upon a deductive coding scheme provided by the NPF and the fitting of that schema to the belief system approach of the Cultural Cognition Project at Yale University. From a theoretical perspective, our analysis shows how two approaches might be applied to better understand how individuals within groups leverage their core beliefs—and their parent cultures—to come to terms with complex information environments via narrative sense-making. But beyond ivory tower curiosity, why should we care? This leads us to our second and more important implication. What stands out to us is the stark differences in the stories told within each focus group, despite being presented with analogous information. The practical implications are not trivial. It is increasingly apparent that it can no longer be assumed that naked information is simply communicated objectively to relevant publics or individuals. Rather, their backgrounds, existing knowledge, affiliations, and their cultures must also be accounted for. While our study does not speak to how better to communicate important information to these populations, it does provide some insight into how culture and groups help individuals navigate complex information environments.

7 Contribution of narrative network analysis to political culture

Finally, we would like to close with some broader observations about the integrating CC theory with an NPF-based narrative network analysis and how it potentially benefits the study of political culture more generally. People tell stories to make meaning of their world, regardless of the political culture typology that one might employ. As such, an NPF-based narrative network analysis can easily travel across cultural approaches. Another advantage of the narrative network analysis is that it manages to address a problem that exists when studying political culture, which is the precise location of culture. Is it carried by the individual? Does it manifest in family units, work locations, political parties? Is the state (or nation) the host of culture? More to the point, regardless of where the culture is thought to reside, the interaction between social units of divergent cultural commitments is likely to be a source of conflict. Since this study utilizes CC measures to categorize individuals and then analyzes the narratives which emerge from the interaction within the group, we can see how differing cultures can help to shape the stories by which individuals make sense of a policy problem. While this approach does not explore the inherent power dynamics that would exist within other social units (such as the family or the workplace), it does take a step toward recognizing the role of the group and the power of homogenous cultural values in generating distinct narrative structures.

Change history

14 August 2019

The article “The stories groups tell, campaign finance reform and the narrative networks of cultural cognition”, written by “Aaron Smith-Walter, Michael D. Jones, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Holly Peterson“.

Notes

On a scale from one to six, where one is strongly disagree and six is strongly agree, potential participants were asked to respond to the following screening question: The way in which congressional campaigns are currently financed and paid for is in need of serious reform. Participants that agreed with the above statement (responses ranging from 4 to 6) continued on to the next selection process where they were screened for their cultural cognition affinities.

For the hierarchy--egalitarianism dimension, agreement with egalitarian affiliated statements received a − 1, while disagreement received a + 1; similarly, for the same dimension, hierarchy affiliated statements received a + 1 for agreement and a − 1 for disagreement. The scores were then aggregated producing a single hierarchy score for each potential participant ranging from − 6 to + 6, where a strongly negative score denoted an egalitarian orientation, while a strongly positive score denoted a hierarchical orientation. The same process was conducted for the individualism--communitarianism dimension. Agreement with individualism affiliated statements received a − 1, while disagreement received a + 1; similarly, communitarian affiliated statements received a + 1 for agreement and a − 1 for disagreement. The scores were then aggregated producing a single summative communitarian score for each potential participant ranging from − 6 to + 6, where a strongly negative score denoted an individualist orientation, while a strongly positive score denoted a communitarian orientation. To test H3, the CC scores were weighted by respondents’ response to the screening question (Mildly Agree = x 1.0; Agree = x 1.25; and Strongly Agree = x 1.50). The idea being that if the issue is seen as more important to an individual, the more likely they are to have developed at least a cursory impression and are able to convey this to the group.

The top quartiles had scores ranging from + 4 to + 6, while the bottom quartiles had scores ranging from − 4 to − 6 for each of the two dimensions. While 10 participants accepted the invitation to participate, actual attendance ranged from 8 to 10 individuals.

These data were collected in conjunction with the Cultural Cognition Project at Yale University and the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University. We thank the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics for their generous grant which made collecting these data possible.

Note that such an approach contrasts the more conventional way to conduct focus groups where efforts might be made to moderate or divert a few dominant focus group participants (e.g. Krueger and Casey 2000; Morgan 1996, 1997) from dominating the conversation. Indeed, such forceful personalities were allowed to thrive in our focus group environment, when they emerged, as they were likely to be powerful cultural foils for the other focus group participants.

Plot was excluded from the analysis as it failed to achieve sufficient intercoder reliability (Scott’s pi = 0.245).

Scores higher than .80 are generally considered acceptable (Lombard et al. 2002).

To address the possibility that a few strong personalities exerted disproportionate influence on the composition of the group narrative Spearman’s Rho was utilized to correlate the CC score of each individual with the percentage of narrative elements that individual contributed during the discussion. CC scores computed for 37 participants ranged from 10 to 18, with a median score of 15. The individual contribution was computed by dividing the total number of coded narrative elements the individual used divided by the total number of narrative elements identified in the focus group (pre- and post- calculated separately). The correlation coefficient for the pre-information focus group conversation was .112, with a 1-tailed significance of .254 (p < .05). The coefficient for the post-information portion was .089 with a 1-tailed significance of .299 (p < .05). Therefore an individual’s cultural cognitive score and desire for reform did not result in increased contribution of elements to the group narrative.

Some tangential observations are worth mentioning. No focus group discussed the topic of campaign finance in specific or technical policy terms. In fact, there was widespread confusion towards campaign finance policy in general. However, group members did speak passionately about their feelings towards elections, towards politicians and others, and used examples often to illustrate their points. Members made mention of current events, politicians and sports players to describe their feelings toward more general topics.

When using the Kruskal–Wallis H, the non-parametric equivalent of ANOVA, the initial result will simply indicate whether there is a statistically significant difference among the several categories tested. If a significant difference is discovered, further analysis of the differences between each of the groups using a Mann–Whitney U test is recommended. However, as the original significance value is p < 0.05, then this p value needs to be divided by the number of group comparisons to establish the 0.01 value for the results of the Mann–Whitney U test, this is known as the Bonferroni correction.

References

Almond, G.A.: Comparative political systems. J. Polit. 18(3), 391–409 (1956)

Almond, G.A., Verba, S.: The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1963)

Black, L.W.: Deliberation, storytelling, and dialogic moments. Commun. Theory 18(1), 93–116 (2008)

Chai, S., Dorj, D., Hampton, K., Liu, M.: The role of culture in public goods and other experiments. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 44(4), 740–744 (2011)

Crow, D.A., Berggren, J.: Using the narrative policy framework to understand stakeholder strategy and effectiveness: a multi-case analysis. In: Jones, M.D., Shanahan, E.A., McBeth, M.K. (eds.) The Science of Stories: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework in Public Policy Analysis, pp. 131–156. Palgrave Macmillan, New York (2014)

Douglas, M.: Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. Pantheon, New York (1974)

Douglas, M., Wildavksy, A.: Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Dangers. University of California Press, Berkeley (1982)

Elazar, D.J.: American Federalism: A View from the States, 4th edn. HarperCollins, New York (1984)

Everett, M., Borgatti, S.P.: Extending centrality. In: Carrington, P.J., Scott, J., Wasserman, S. (eds.) Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2005)

Fisher, P.I.: Definitely not moralistic: state political culture and support for Donald Trump in the race for the 2016 presidential nomination. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 49(4), 743–747 (2016a)

Fisher, P.I.: The political culture gap: Daniel Elazar’s subculture in contemporary American politics. J. Polit. Sci. 44, 87–108 (2016b)

Gilovich, T.: How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Hofstede, G.: Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks (2003)

Jones, M.D.: Leading the way to compromise. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 44(4), 720–725 (2011)

Jones, M.D.: Advancing the narrative policy framework? The Musings of a potentially unreliable narrator. Policy Stud. J. 46(4), 724–746 (2018)

Jones, M.D., McBeth, M.K.: A narrative policy framework: clear enough to be wrong? Policy Stud. J. 38(2), 329–353 (2010)

Jones, M.D., Shanahan, E.A., McBeth, M.K.: The Science of Stories: Applications of Narrative Policy Framework in Public Policy Analysis. Palgrave Macmillan, New York (2014)

Jorgensen, P.D., Song, G., Jones, M.D.: Public support for campaign finance reform: the role of policy narratives, cultural predispositions, and political knowledge in collective policy preference formation. Soc. Sci. Q. 99(1), 216–230 (2018)

Kahan, D.M.: Cultural cognition as a conception of the cultural theory of risk. In: Roeser, S., Hillerbrand, R., Sandin, P., Peterson, M. (eds.) Handbook of Risk Theory. Springer, Dordrecht (2012)

Kahan, D.M., Braman, D., Gastil, J., Slovic, P., Mertz, C.K.: Culture and identity-protective cognition: explaining the white-male effect in risk perception. J. Empir. Legal Stud. 4(3), 465–505 (2007)

Kahan, D.M., Braman, D., Monahan, J., Callahan, L., Peters, E.: Cultural cognition and public policy: the case of outpatient commitment laws. Law Hum. Behav. 34(2), 118–140 (2010a)

Kahan, D.M., Braman, D., Cohen, G.L., Gastil, J., Slovic, P.: Who fears the HPV vaccine, who doesn’t, and why? An experimental study of the mechanisms of cultural cognition. Law Hum. Behav. 34(6), 501–516 (2010b)

Kahan, D.M., Jenkins-Smith, H.C., Braman, D.: Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J. Risk Res. 14(2), 147–174 (2011)

Krueger, R.A., Casey, M.A.: Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks (2000)

La Raja, R.: Small Change: Money, Political Parties, and Campaign Finance Reform. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor (2008)

La Raja, R.J., Schaffner, B.: Explaining the unpopularity of public funding for congressional elections. Elect. Stud. 30(3), 525–533 (2011)

Lockhart, C.: Specifying the cultural foundations of consensual democratic institutions. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 44(4), 731–735 (2011)

Lodge, M., Taber, C.: The rationalizing voter: unconscious thought in political information processing. Working Paper, SSRN (2007)

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., Bracken, C.C.: Content analysis in mass communication: assessment and reporting intercoder reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 28(4), 587–604 (2002)

Mamadouh, V.: Grid-group cultural theory: an introduction. GeoJournal 47(3), 395–409 (1999)

McBeth, M.K., Jones, M.D., Shanahan, E.A.: The narrative policy framework. In: Sabatier, P.A., Weible, C.M. (eds.) The Theories of the Policy Process, 3rd edn, pp. 225–266. Westview Press, Boulder, CO (2014)

McBeth, M.K., Shanahan, E.A., Jones, M.D.: The science of storytelling: measuring policy beliefs in Greater Yellowstone. Soc. Nat. Resour. 18, 413–429 (2005)

Milyo, J.D., Primo, D.M.: Public attitudes and campaign finance: report prepared for the campaign finance task force. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Public-Attitudes-and-Campaign-Finance.-Jeffrey-D.-Milyo-David-M.-Primo.pdf (2017). Accessed 24 Sept 2018

Morgan, D.L.: Focus groups. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 22, 129–152 (1996)

Morgan, D.L.: Focus Groups as Qualitative Research, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (1997)

Morgan, D.R., Watson, S.S.: Political culture, political system characteristics, and public policies among the American states. Publius J. Fed. 21(2), 31–48 (1991)

Overacker, L.: Money in elections. The Macmillan Company, New York, NY (1932)

Pew Research Center: The public, the political system and American Democracy. http://www.people-press.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/04/4-26-2018-Democracy-release1.pdf (2018). Accessed 10 Oct 2018

Rombach, M.P., Porter, M.A., Fowler, J.H., Mucha, P.J.: Core-periphery structure in networks. J. Appl. Mech. 74(1), 167–190 (2014)

Ryfe, D.M.: Narrative and deliberation in small group forums. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 36(1), 72–93 (2006)

Sabatier, P.A., Jenkins-Smith, H.C. (eds.): Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Westview Press, Boulder, CO (1993)

Shanahan, E.A., Jones, M.D., McBeth, M.K.: Policy narratives and policy processes. Policy Stud. J. 39(3), 535–561 (2011)

Shanahan, E.A., Jones, M.D., McBeth, M.K., Lane, R.: An angel on the wind: how heroic policy narrative shape policy realities. Policy Stud. J. 41(3), 453–483 (2013)

Shanahan, E.A., Jones, M.D., McBeth, M.K.: How to conduct a narrative policy framework study. Soc. Sci. J. (2018a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2017.12.002

Shanahan, E.A., Jones, M.D., McBeth, M.K., Radaelli, C.M.: The narrative policy framework. In: Weible, C.M., Sabatier, P.A. (eds.) Theories of the Policy Process, 4th edn. Westview Press, New York (2018b)

Shanahan, E.A., Adams, S.M., Jones, M.D., McBeth, M.K.: The blame game: narrative persuasiveness of the intentional causal mechanism. In: Jones, M.D., Shanahan, E.A., McBeth, M.K. (eds.) The Science of Stories: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework in Public Policy Analysis, pp. 69–88. Palgrave Macmillan, New York (2014)

Shanahan, E.A., Raile, E.D., French, K.A., McEvoy, J.: Bounded stories: how issue frames and narrative setting help to construct policy realities. Policy Stud. J. 46(4), 922–948 (2018c)

Shaw, G.M., Ragland, A.S.: The polls–trends: political reform. Public Opin. Q. 64(2), 206–226 (2000)

Smith, M.M., Williams, G.C., Powell, L., Copeland, G.A.: Campaign finance reform: the political shell game. Lexington Books, London (2010)

Smith-Walter, A.: Victims of health-care reform: Hirschman’s rhetoric of reaction in the shadow of federalism. Policy Stud. J. 46(4), 894–921 (2018)

Smith-Walter, A., Peterson, H.L., Jones, M.D., Reynolds Marshall, A.N.: Gun stories: how evidence shapes firearm policy in the United States. Polit. Policy 44(6), 1053–1088 (2016)