Abstract

This research note uses in-depth interviews, ethnographic observations, and archival records to examine the self-understandings of think tank-affiliated policy experts. I argue that policy experts draw on a series of idioms—those of the academic scholar, the political aide, the entrepreneur, and the media specialist—to construct a unique albeit synthetic professional identity. The essence of the policy expert’s role lies in a continuous effort to balance and reconcile the contradictory imperatives associated with these idioms. An analysis of the policy expert’s mixed “professional psyche” offers a useful point of entry into the objective social structure of the think tank.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the last four decades, the intellectual pronouncements of a growing breed of organizations known as think tanks have become fixtures of public debate in America. As the number of think tanks in the US has roughly quadrupled (Rich 2004), the public policy specialists employed at these organizations (hereafter “policy experts”) have taken on a more visible political role. Policy experts commonly testify before Congress (Rich and Weaver 1998; McCright and Dunlap 2003), speak as news media pundits (Rich and Weaver 2000; Abelson 2002), and draft transition manuals for incoming presidential administrations (see, e.g., Feulner 1980). Yet despite the proliferation and growing visibility of think tanks and policy experts in the US, social scientists have paid relatively little attention to them, leaving certain fundamental questions unanswered.

This paper addresses a series of related questions: how do think tank-affiliated experts understand and talk about their own role?Footnote 1 What styles, skills, and sensibilities do they regard as central to their mission? What are the major lines of separation among them? My argument is that, lacking a conventional definition of what it means to be a policy expert, such actors improvise one using a mixture of ready-made cultural materials supplied by the more established institutions on which they depend for their resources and credibility. Policy experts draw especially on four idioms to characterize their own role—those of the academic scholar, who generates authoritative knowledge according to collectively defined standards of rigor and cognitive autonomy; the policy aide, who must familiarize himself with the unique rules of order, procedural details, and temporal rhythms of electoral politics; the business entrepreneur, who must be an effective salesperson in a competitive marketplace, and the media specialist, who must disseminate knowledge in a format that is both accessible and compelling to the wider public. While each idiom reveals an important dimension of the policy expert’s role, it is in the never-ending attempt to balance and reconcile these contradictory functions that I find the essence of the policy expert’s professional identity.

My discussion is divided into two sections. In the first part, I will describe how the four idioms listed above guide and condition the self-understandings of policy experts. Each trope, I argue, functions both as an anchoring metaphor and as a bundle of literal claims about the proper style and manner of a policy expert. The second section considers the policy expert’s dispositional hybridity as a window into the objective social structure of the think tank. Here I will argue that the mixed professional stance common among policy experts arises out of the think tank’s intermediate location in the social structure relative to the worlds of academia, politics, business, and the media.

The policy expert as academic scholar

The symbolic point of departure from which policy experts construct their mixed self-descriptions is an idiom of academic production. Policy experts commonly invoke the figure of the university scholar in discussing their own role. In this language, the policy expert should aim to develop cumulative knowledge based on rigorous empirical data for publication in books and articles. He should possess a sharp mind, keen analytical abilities, advanced academic training, and freedom from both partisan bias and political and economic constraint.Footnote 2 As the president of the Brookings Institution told the Washington Post in 2004, “We make a real effort to keep our policy [analyses] objective in the sense that we let chips fall where they may as we identify the big questions and seek the big answers—rather than letting our product be skewed in any fashion by ideological or partisan preferences.”Footnote 3

The academic idiom commonly extends from the actor to the organization: if the policy expert is like a scholar, then the think tank is said to be like a “university without students.”Footnote 4 Indeed, many think tanks refer to their expert staff members as “scholars” and “fellows,” irrespective of their actual affiliations or credentials. Many also have endowed staff positions reminiscent of university professorships. (For example, the Heritage Foundation has the Chung Ju-Yung Fellow for Policy Studies, Brookings the Bruce and Virginia MacLaury Chair in Economic Studies, and AEI the Joseph J. and Violet Jacobs Scholar in Social Welfare Studies.) Other think tanks explicitly compare themselves to universities or describe their intellectual production as “scholarship.” In 1997, for example, the Cato Institute launched a division called the “Cato University” that offered educational seminars for aspiring libertarians.Footnote 5 Finally, a few think tanks, including the Brookings Institution, have world wide web addresses with the suffix “.edu”—and at least one, the RAND Corporation, has a degree-granting capacity.Footnote 6

Policy experts invoke the language of academic production in personal interviews as well, as the following interview excerpts illustrate:

- I::

-

What are the major considerations discussed in a board meeting?

- R::

-

Our board wants to know if we’re publishing good quality scholarship and if it contributes to making America a better place.Footnote 7

***

- I::

-

What are the forms of expertise that you have to have?

- R::

-

...You can’t sell superficial ideas on any sustained basis, so you also have to be generating serious analysis...so that your work is credible and is recognized by academic leaders and policy leaders as something that they should pay attention to.Footnote 8

***

- I::

-

What are the marks of a good research product in the context of the policymaking process?

- R::

-

Well, good research is good research, whether it’s policy-oriented or not. It’s transparent. It’s replicable.Footnote 9

***

- GA::

-

Brookings has a very—it’s like a university. The range of views there, the range of opinions. The one thing that is consistent is that the people they have there are of the highest caliber. They have all the badges they need to accumulate to be viewed as an expert.Footnote 10

The fact that policy experts adopt an idiom of academic production is not surprising given that the earliest think tanks were founded with the express purpose of spanning the divide between universities and politics (Critchlow 1985; Smith 1991a, b). The original mission statement of the Brookings Institution, for example, reads in part, “In its conferences, publications, and other activities, Brookings serves as a bridge between scholarship and policymaking, bringing new knowledge to the attention of decisionmakers and affording scholars greater insight into public policy issues.”Footnote 11 Far less obvious, however, is the fact that policy experts actively downplay their resemblance to scholars when speaking about other aspects of their role.

The policy expert as political aide

A second language of professional duty imagines the policy expert not as a scholar, but as a political aide whose main obligation is to be familiar with the distinctive rules of order, procedural details, temporal rhythms, and norms of reciprocity guiding American politics. In this trope, the essential characteristics of a policy expert include the ability to anticipate “hot” policy issues before they arise and the capacity to churn out useful reports quickly to coincide with these developments. Like a congressional aide, the policy expert should possess detailed knowledge of the workings of legislative and executive agencies and a familiarity with the language of policy debate. Prior political experience is a valuable asset, and the measure of a good policy report is less its scholarly rigor than its functionality in the policymaking process. Being “too scholarly,” in fact, is a fatal flaw.Footnote 12 As the executive director of the Northeast-Midwest Institute explains, “You have to...know how to move [an idea] through the policy labyrinth that is this legislative body and administrative body”:

- I::

-

And what are the considerations that are taken into account?

- R::

-

Well, it’s various things. Who sits on what [congressional] committee? Who has seniority? Who sets the policy agenda for that committee? What other stakeholders can be aligned with the proposal that you have that would make it more acceptable to the powers that be on the relevant committees that have to deal with this?

- I::

-

Coalition-building?

- R::

-

Yeah, coalition building. Vote-counting, in a way. At the end of the day, on a particular subcommittee, are you going to get out of there with a favorable vote or not? You’ll not always, but often, have to think, “Will it sell on the Hill?”Footnote 13

According to one policy expert, “Having former government service helps a lot. I think there’s a certain aura that comes with, ‘He is the former ambassador to the Soviet Union,’ or, ‘He is the former Undersecretary of State.’ You know, the fact that it was 20 years ago and you’re kind of pontificating on a subject that you did absolutely nothing on at that point in your life, that doesn’t matter. It’s just, ‘The former this.’ You know, people need a title, and that helps.”Footnote 14

According to this metaphor, a policy expert succeeds by positioning himself as an effective player in the policymaking process—for example, by supplying legislative testimony, briefing members of Congress, or writing “talking points” memoranda for candidates and politicians. Cultivating access to political networks and staying on top of day-to-day policy developments are “musts” for the policy expert. According to one Brookings fellow, a good policy expert “tries to keep current, I mean, to be working on things that are relevant [to policy debates].”Footnote 15 The president of the Economic Strategy Institute likewise explains, “You have to be in tune to [policy] developments and take advantage of opportunities to use those developments and respond to them by writing articles, getting that in the press, getting testimony up on the Hill....You have to understand the issues and the players in the policy areas that you’re dealing with.”Footnote 16 Failing to generate studies with obvious relevance to political debate can marginalize a policy expert and compromise his or her ability to attract media attention and financial support.

The policy expert as entrepreneur

A third language of professional duty imagines the policy expert, not as a scholar or a policy aide, but as an entrepreneur in a “marketplace of ideas.” In this trope, the central goal is to market one’s intellectual wares to three kinds of consumers: legislators, who “buy” ideas by incorporating them into policy; financial donors, whose purchase is somewhat more literal because it involves giving money to the think tank; and journalists, who figuratively buy think tank studies by citing them and quoting their authors. In this metaphor, a good policy expert must possess the attributes of a successful marketer: “people skills,” a taste for self-promotion, and a knack for re-packaging ideas to broaden their appeal. The commercial metaphor commonly extends from the actor to the organization: like corporations vying for market share, think tanks are said to compete with one another in a crowded “marketplace of ideas.”

Policy experts routinely invoke the concepts of salesmanship and commercial transaction to characterize their setting and the attributes needed to excel in it. Asked to name the marks of a good policy expert, for example, the founder and president of the Economic Strategy Institute explains:

You gotta be a salesman. You have to present your ideas crisply, convincingly, interestingly, and you have to have enormous energy. You have to have what the salesmen call “closing ability.” Not only do you make the presentation, but you have to ask for the order. And the order may be a donation or the order may be a bill or a policy idea that you’re trying to sell. But you have to be able to ask for the order and get it.Footnote 17

Edwin Feulner, the president of the Heritage Foundation, reflects on the secrets of a successful think tank in the following terms: “The key ingredient is the person who heads it...must be entrepreneurial enough to see the unique need [and] salesman enough to convince others (donors, professors to write the papers, and policy makers and journalists) to listen to him and his people.”Footnote 18 Feulner used the same trope in a 1985 speech: “It takes an institution to help propagandize an idea—to market an idea.... Proctor and Gamble does not sell Crest toothpaste by taking out one newspaper ad or running one television commercial. They sell and re-sell it every day, by keeping the product fresh in the consumer’s mind. [Think tanks] sell ideas in much the same manner” (Feulner 1985).

A veteran of several think tanks extends this trope by distinguishing between a good policy expert and someone who is merely a good thinker:

There are people who are wonderful thinkers, wonderful writers, but they feel very uncomfortable promoting themselves. And what you need [in a think tank] is self-promoters. I think that some of the best people in this game have been shameless self-promoters....They’ve got to want to sell their idea. They’ve got to be willing to make the phone calls to the press, push to get on the TV show, stay up nights writing the extra op-ed piece. People who are neurotic that way often are the best people. People who say, “Well, I’ve said all I have to say on that idea. It’s here. Now I want to go and do something else,” they don’t tend to be as successful.Footnote 19

In the words of one think tank director, a policy expert should be “innovative” and always able “to come up with sort of a new twist or a new angle on an idea.”Footnote 20

The salesmanship idiom is not new, having crystallized in the widely used expression “policy entrepreneur” by the early 1980s.Footnote 21 While the imagery might seem more in keeping with a conservative vision of policy expertise than a progressive one, its use is not limited to those on the right. Progressive journalist and Center for American Progress fellow Eric Alterman, for example, uses this trope in an interview:

- I::

-

Can you tell me something about the set of skills that you need in order to be a successful think tanker, for lack of a better term?

- R::

-

Well, there is sort of a public policy entrepreneur personality...which basically involves being a good schmoozer. That’s really all there is to it.

- I::

-

Schmoozer with journalists? With political figures?

- R::

-

With whomever. I mean, a lot of academics are very inarticulate, more so in the hard sciences than in the short [sic] sciences. You know, they write essays and they’re shy and stuff. [In] think tanks, you’re better off being somewhat gregarious and not being that shy about selling yourself.

The policy expert as media specialist

Newer and less salient than the first three idioms is a fourth trope emphasizing the resemblance between policy experts and communications specialists. In this language, a policy expert must exhibit a knack for writing in plain language and a willingness to compose short, compact studies in a form similar to press releases or newspaper articles. Policy experts must “have a sense of what’s going to be newsworthy,” in the words of one respondent.Footnote 22 They should be “able to consolidate their technical, complex ideas into something that is really very understandable—that is, a sound bite, if you will.” The president of ESI summarizes the point in this way: “Public relations, media relations—or media savvy—is a very important aspect of the business.”Footnote 23 Says another policy expert: “It’s true in journalism and it’s true in think tanks: to be a successful think tank person, you need to be able to write in a way that is understandable to non-specialists....It’s a matter of making complicated matters understandable in colloquial terms.”Footnote 24

When asked to describe a good policy argument, one policy expert says,

First of all, it has to be intelligible. It has to be brief, and digestible. We don’t tend to generate large major reports....By and large what we produce is less than ten pages and our talking points are one page. And our columns are 750 words. They’re op-ed length because we want people to actually be able to read them and digest them and apply them. So I think the most important characteristic of the work we’re trying to put out is that it be accessible and respectful of people’s information overload, and their limited time.Footnote 25

For some policy experts, comfort and eloquence on television are prized assets that go hand in hand with good writing ability. As a Competitive Enterprise Institute fellow explains, “With doing broadcast interviews—well, specifically TV—your body language is so important. As important, if not more important, than actually the words that you use. [CEI president] Fred [Smith, Jr.] is very good at it. He’s got the energy and the quips, and the producers love him, so he’s on TV a lot. And of course he does radio well, too. But his energy—he really does TV. That’s his forte.”Footnote 26

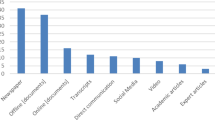

The use of a communications model reflects one of the major tendencies among think tanks since the 1970s. Once media-shy, many think tanks now employ communication specialists, maintain media outreach departments, and reward their fellows for publishing op-ed pieces in the newspaper and appearing on television (Weaver 1989).Footnote 27 As the importance of publicity has grown, policy experts have developed fine-grained categories for assessing the news media universe. Asked to name the most desirable outlets in which to be quoted, cited, or to publish their work, few find themselves at a loss for words, as these interview excerpts suggest:

[In the] print media, the place to be is the New York Times. The Wall Street Journal, if you’re an economist. The Washington Post for local Washington exposure, including Congress and the government, but the Washington Post doesn’t have the national reach that the Times and the Journal do.Footnote 28

***

The Wall Street Journal or the Financial Times. On trade or budget [issues], those are the papers that you want to reach for. The New Republic or the Weekly Standard are more niche-oriented weeklies, one being more liberal, one being more conservative, but we have friends in both.Footnote 29

***

If you want to get your article talked about, it had better be in the Post, the Times, or the Journal. In magazines, The New Republic, the Atlantic Monthly. I think to a lesser extent The Weekly Standard and National Review. ...Harpers, I think, has become kind of ridiculous. And the Atlantic Monthly...has just soared beyond Harpers.Footnote 30

***

- R::

-

Andy Kohut, who’s my boss at Pew, places incredibly great store in the [PBS Jim] Lehrer Show. It’s true, they’ll give you five to seven minutes or whatever as opposed to forty-five seconds. It’s true that thoughtful people watch it....

- I::

-

You’re on [NPR’s] Marketplace.

- R::

-

Yeah, I’m on Marketplace. But that’s not nearly as good as being on All Things Considered. You know, just a bigger audience and you get more time and, again, a thoughtful audience. [It’s] useful in part because I’m amazed at the number of people who listen to NPR commuting. You know, serious people.Footnote 31

On the thorny synthesis of contradictory roles

Disentangling the idioms on which policy experts draw to arrive at their unique self-understandings is a valuable but potentially deceptive analytical act. This is because few policy experts are content to choose just one of the models listed above. Instead, they share a professional ethos built on the goal of mastering and juggling all four. The importance of merging disparate styles is a ubiquitous theme in the discourse of most policy experts. For example, a Brookings Institution fellow describes how her organization recruits new staff members:

- I::

-

If you’re hiring a new scholar here at Brookings, what are the marks of a good policy researcher? Who are you looking for?

- R::

-

Good track record in writing stuff, usually.

- I::

-

Writing, like, op-ed pieces, or writing in academic journals?

- R::

-

Writing both. Brookings would look for somebody who had written a really good book on something or a series of not-too-academic journal articles. But if there had been some op-eds and things, that would be a plus. If this was a person who was a good speaker and presenter, that would be a plus.Footnote 32

The president of the Competitive Enterprise Institute offers a vivid analogy for the difficulty of juggling multiple roles:

I use the analogy—I’ve used it for years—public policy is...like having a vaudeville act or something. You go up on the stage and you’re juggling and you’re singing, and you’re balancing. And then you run behind the curtain and run up in the audience and applaud madly. And then you run back up on the stage and you juggle. And then you run back and applaud madly. If you do it right, all of a sudden other people start applauding and you’ve got a hit.Footnote 33

However, what may appear first as a “quadruple bind”—or a four-sided pursuit of academic, political, entrepreneurial, and media authority—turns out, on closer inspection, to have a bipolar structure. This is because the goals associated with three of the four idioms—namely, political access, funding, and publicity—are more easily brought into line with one another than any of them can be reconciled with the pursuit of academic consecration. Political access, for example, is often a boon to a policy expert’s media visibility, which may in turn positively shape his or her fundraising capacity. The goal of scholarly rigor, on the other hand, more often demands a certain insulation from commercial pressures, freedom from political censorship, and relative indifference to publicity. Thus, overlaying the four-cornered structure of the policy expert’s role is a master opposition between intellectual credibility, on the one side, and temporal power, on the other.

Naturally, most policy experts cannot truly balance the two demands—first, because each one requires a great deal of social learning, and second, because the sensibilities they require tend to be at loggerheads. As the president of the Institute for Policy Studies laments: “Mostly all those skills don’t come together in one person, and so...almost everyone we hire, I believe, is stronger in one side or the other.”Footnote 34 A separation thus appears among policy experts that parallels an opposition described by journalist Bruce Reed:

Strip away the job titles and party labels, and you will find two kinds of people in Washington: political hacks and policy wonks. Hacks come to Washington because anywhere else they'd be bored to death. Wonks come here because nowhere else could we bore so many to death. These divisions extend far beyond the hack havens of political campaigns and consulting firms and the wonk ghettos of think tanks on Dupont Circle. Some journalists are wonks, but most are hacks. Some columnists are hacks, but most are wonks. All members of Congress pass themselves off as wonks, but many got elected as hacks. Lobbyists are hacks who make money pretending to be wonks. The Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the entire political blogosphere consist largely of wonks pretending to be hacks. “The Hotline” is for hacks; National Journal is for wonks. “The West Wing” is for wonks; “K Street” was for hacks. After two decades in Washington as a wonk working among hacks, I have come to the conclusion that the gap between Republicans and Democrats is as nothing compared to the one between these two tribes.Footnote 35

In this language, “wonks” are the more academically affiliated policy experts, or those who bring to the production of policy research technical skills and credentials; “hacks,” by contrast, are those who enter this contest with fewer educational credentials, but tend to be more closely aligned with centers of political, economic, and media power.

Nevertheless, policy experts try to walk the thin line between the two. The conflict between intellectual and temporal authority obtains within the “professional psyche” of the individual policy expert. “We’re Janus-faced, looking in both directions,” says one Brookings Institution fellow.Footnote 36 Other policy experts describe feeling pushed and pulled in opposite directions by the demands of their job. For example, some think tanks encourage their fellows to advise politicians and candidates for public office, even while requiring them to separate such consulting from their official organizational duties. Brookings Institution fellows are permitted to advise candidates “in a personal capacity, outside regular business hours and without use of Brookings resources,” while the American Enterprise Institute says that its “scholars and fellows frequently do take positions on policy and other issues, including explicit advocacy for or against legislation...[but] when they do, they are speaking for themselves and not for AEI or its trustees or other scholars or employees.”Footnote 37 The Institute for Policy Studies is similarly equivocal in its claim that it “works with but is independent of political parties and movements.”Footnote 38 A Center for American Progress fellow describes the sense of liminality that can result from orienting oneself to multiple social worlds: “I personally exist in a kind of never-never land of the nexus of all of these worlds—journalism, academia, think tank, politics—and none of them entirely satisfy me.”Footnote 39

A certain Faustian quality thus marks the policy expert’s mission. Like the protagonist of Goethe’s tragedy, who is driven by an insatiable desire to learn everything that can be known, a policy expert faces an assignment that is cumbersome at best and impossible at worst. This much becomes clear from the Manhattan Institute’s stated goal of “Combining intellectual seriousness and practical wisdom with intelligent marketing and focused advocacy.”Footnote 40 Because of the “three against one” pattern described above, the policy expert’s stance toward the academic world tends to be one of special ambivalence. Typically, this stance begins with a statement of kinship; for instance, many policy experts praise their own organizations in a manner that underscores their association with research universities: “Like a good academic institution, there is a real protection of academic freedom here,” says one fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.Footnote 41 Yet stated affinities with academia often give way to sharp critiques of “ivory tower” esotercism and public disengagement. Says a former vice president of the Heritage Foundation: “There are countless [academic] disciplines that are very inward looking. I would say inward looking, incestuous, and not very interesting. And that don’t add much, don’t have much wisdom to contribute to anybody outside of their discipline.”Footnote 42

The criticism aimed at academic scholars by policy experts has two components. The first is that academic social science is marred by empty or ritualistic displays of methodological proficiency. Many policy experts, for example, argue that the statistical modeling techniques favored by their academic counterparts contribute little to actual policymaking discussions. In the view of one policy expert, “These economists like to build their models that have nothing to do with the real world and that’s one of the reasons I think the think tanks have risen. [Think tanks] are more interested in talking about what the real world is.”Footnote 43 Another policy expert makes a similar point: “In economics, they put a lot of stock in economic modeling and, I have to say, I just find that such a waste of time because I could show you anything you want in an economic model. The question is, is it really saying anything about the world?...To me it’s just absolutely pointless. It is a ritual that gets people tenure.”Footnote 44 The second part of the policy expert’s critique of scholars, and a curious analogue to the criticism of statistics, is that the discursive turn in the humanities and social sciences encourages excessive abstraction and relativistic thinking. A Heritage Foundation fellow explains his view:

I think what had happened [when Heritage began] is that professors had become increasingly more and more arcane in their studies, had turned inward, affected by the various trends which were going on at that time, whether it was Foucault or Derrida and all the rest of those guys. You know, “Nothing is real. It’s all relative.” Well, that’s not exactly what a politician wants. He’s looking for some answers to a particular problem, not, “Well, there is no answer.”

From the perspective of many policy experts, the growth of formal modeling techniques and the discursive turn in the humanities and social sciences are two sides of the same coin of esotericism.

Most policy experts are, of course, aware of the counter-accusation that they are “failed academics,” and that their negativity toward the university springs more from pride or defensiveness than from an honest appraisal of academic research. They are mindful, for example, that academic scholars may perceive their work as lacking rigor. In response, many emphasize the special skills they have acquired in the course of their time at the think tank. For example, an American Enterprise Institute fellow and ex-political science professor reflects on the considerable level of mastery needed to write newspaper op-ed pieces: “This is an acquired skill and something that is difficult for most academics to do. If you are used to writing journal articles or writing books, there is no discipline that comes to bear in the sense that you have got to limit this to a small space.”Footnote 45 Compared with academic writing, this respondent says, drafting op-ed pieces for the newspaper “is harder to do. It takes more internal discipline....You don’t have the luxury of meandering around. You’ve got to focus and pinpoint.”

Many policy experts also emphasize their greater relevance to policymaking, including the fact that temporality of policy research is closer to that of policymaking than to scholarship. For example, to the question, “What are the marks of a good researcher here?” the director of the California Institute replied, “Timeliness. It’s not just seeing something, but it’s also getting it out fast. I think the value here is being able to rip things out in a hurry. The staff here is really good at that.”Footnote 46 A veteran of several think tanks likewise observes that, “The policy process occurs in real time, and so coming out with a really useful study two years after the reauthorization of the bill is of no earthly use to anyone who is engaged in the real policy process. So one thing think tanks are aware of is the policy schedule.”Footnote 47 The fact that policy schedules constitute “real time” in the minds of some policy experts illustrates their orientation to the temporality of the political field, even as it distances them from the elongated cycles of academic production.

Another point of difference between scholarly work and policy expertise lies in their separate languages. A Center for American Progress fellow explains that, “There are...folks in academic life who have learned a certain style of communication that works very well within their own peer group but doesn’t translate easily into either the Washington environment or the broader national policy drama.”Footnote 48 As a Century Foundation vice president similarly observes, “Academics are especially forced to be very narrow in their focus... [and] have no incentive to do other kinds of work that would be broader policy-oriented work if they’re situated in an environment where they’re trying to get tenure.”Footnote 49 A policy expert, by contrast, must speak the language of political debate. As the president of the Brookings Institution points out, “One difference between a think tank and a university is that we do not go in much for ‘pure’ research—which is to say, we emphasize research that is relevant and useful to policymakers.”Footnote 50

Given their asymmetrical pattern of commitment to the four professional idioms, and the inner conflict to which it gives rise, why do policy experts not simply discard the academic model altogether? Why not embrace only the political, entrepreneurial, and media models? The answer, undoubtedly, is that the idiom of academic production provides policy experts with an indispensable font of authority, as well as a means of symbolic separation from lobbyists, activists, and political aides. Without this connection, policy experts would run the risk of looking too much like their K Street or Capitol Hill cousins, whose material resources and political access inevitably overshadow their own. In sum, while the scholarly component of the policy expert’s repertoire may be difficult to reconcile with the other idioms, it is nonetheless critical to the strategy as a whole. The assertion of scholarly proficiency signals insulation from political and economic constraint, the hallmark of any intellectual’s authority.

Conclusion

Across writings both popular and scholarly, the image of the think tank-affiliated policy expert oscillates between two radically different profiles. On the one side is the image of the “bona fide intellectual,” a picture invoked whenever policy experts are called to testify before Congress, or whenever a journalist juxtaposes a policy expert’s pronouncements with those of academic social scientists, thereby suggesting their equivalence. We can see the same idea reflected in the impulse to classify policy experts as “public intellectuals.” In 2006, for example, the Economist (under the heading “Public intellectuals are thriving in the United States”) cited the existence of “Grand Academies in the form of lavishly-funded think-tanks, well over 100 of them in Washington alone” to support its claim that in “the world of public policy today...it is America that is the land of the intellectuals and Europe that is the intellect-free zone.”Footnote 51 The image of the policy expert as an intellectual is also reproduced in the scholarly literature, especially in studies carried out in the pluralist tradition, which usually commence by granting think tanks their “independence” by definitional fiat.Footnote 52

On the other side is the widespread notion that a policy expert is actually a “political mercenary,” or essentially a lobbyist in disguise. Christopher Buckley’s satirical novel Thank You for Smoking captures this idea in its sardonic portrayal of a think tank-like organization called the Academy of Tobacco Studies which operates as a shameless front group for the tobacco industry. (The novel’s main character, Nick Naylor, is a charismatic but disreputable PR virtuoso who boasts of his ability to defend virtually any claim, no matter how untenable.) One finds a similar portrait of the policy expert in certain media accounts, such as the National Public Radio series, “Under the Influence,” whose title implied that policy experts are marked by a combination of subservience and mental impairment. Finally, in academic discourse, studies carried out in the elite theory tradition inaugurated by C. Wright Mills yield a picture of the policy expert that is quite compatible with the idea of a political mercenary (Dye 1978; Peschek 1987; Domhoff 1999).

This piece moves the discussion about policy experts beyond the false dichotomy of the “mercenary” and the “intellectual.” I have argued that policy experts must undertake a never-ending effort to balance and reconcile several contradictory functions. Because their legitimacy as intellectuals turns on the ability to signal their autonomy, they must continually proclaim their association with academic production, even as they work to downplay it in other aspects of their role. Thus, while it would be too simplistic to dismiss the scholarly aspect of the policy expert’s role as “just a veneer,” nor can we forget that the same expert’s intellectual production is always hedged about on all sides by a set of profound political and economic constraints.

Notes

My analysis is based on 43 formal interviews with representatives from think tanks and proximate institutions, archival records gathered from more than a dozen manuscript collections, and ethnographic fieldwork conducted at various think tank-sponsored events. The interview subjects included think tank founders and upper managers, rank-and-file researchers and staff members, and people who deal routinely with the work of think tanks, such as congressional staff members, newspaper and magazine reporters, and administrators of philanthropic foundations. The archival records include organizational histories, personal letters and memoirs, mission statements, biographical and autobiographical accounts, and materials related to the founding and decision-making processes of think tanks.

I use the pronoun “him” not for stylistic purposes but to reflect the predominantly male make-up of the think tank world. For example, in 2001, Washington Post columnists Morin and Deane (2001) reported on the gender imbalance among policy experts at seven major think tanks (Urban, CSIS, Brookings, Heritage, Cato, AEI, and IPS). In combination, their count showed 279 men (67.9%) and 132 women (32.1%) working as expert staff members at these organizations. The only think tank in the group that had more female than male policy experts was the Institute for Policy Studies (11 to 6). The most unbalanced think tank was the Cato Institute (35 men, 1 woman).

Washington Post online chat, http://www.washingtonpost.com/, retrieved on September 14, 2004.

See http://www.cato-university.org/ , retrieved on June 15, 2006.

The Frederick S. Pardee RAND Graduate School awards degrees in policy analysis, which the organization describes as “a multidisciplinary, applied field that tries to use research to unlock difficult policy problems.” See http://www.prgs.edu/curriculum , retrieved on July 31, 2006.

Author interview, David Boaz, Cato Institute, November 24, 2003.

Author interview, Clyde Prestowitz, Economic Strategy Institute, July 28, 2003.

Author interview, James Weidman, Heritage Foundation, June 26, 2003.

Author interview, Greg Anrig, Century Foundation, November 22, 2003.

See, for example, Brookings Institution (2007).

Reflecting on the American Enterprise Institution’s declining status in the think tank world in the 1980s, Heritage Foundation fellow Lee Edwards reports, “They [had] become more interested in debating the issues, not [in] having a point of view. They had also gotten into the habit of doing big long studies, fat studies and volumes, and so forth—being a little too, in their writing, perhaps a little too scientific.” Author interview, Lee Edwards, Heritage Foundation, July 8, 2003.

Author interview, Richard Munson, Northeast-Midwest Institute, July 10, 2003.

Author interview, Bruce Stokes, National Journal and Council on Foreign Relations, June 30, 2003.

Author interview, Alice Rivlin, Brookings Institution, February 11, 2004.

Author interview, Clyde Prestowitz, Economic Strategy Institute, July 28, 2003.

Author interview, Clyde Prestowitz, Economic Strategy Institute, July 28, 2003.

Washington Post online chat, http://www.washingtonpost.com/, retrieved on September 11, 2004. Feulner went on to explain the meteoric rise of his organization in these terms: “If an entrepreneur markets what people want, he will be successful. That’s what it’s all about.”

Author interview, Bruce Stokes, National Journal and Council on Foreign Relations, June 30, 2003.

Author interview, Richard Munson, Northeast-Midwest Institute, July 10, 2003.

The earliest use of this term in a major newspaper appears to have been in Hall (1983). A notable use of the expression is in Rothenberg’s (1987) profile of policy expert Pat Choate, “The Idea Merchant”:

Choate is known in Washington as a “policy entrepreneur,” part of a small community of academics and writers whose articles and speeches and fat Rolodex files help to set the national political agenda. Says William A. Galston of the Roosevelt Center for American Policy Studies, a liberal think tank: “A policy entrepreneur is analogous to the entrepreneur in the private sector. He is the person who creates the venture, who invents the concept of the product and then goes out and markets it.” The difference, Galston adds, is that “Pat Choate’s working with political capital, not cash.”

Author interview, Richard Munson, Northeast-Midwest Institute, July 10, 2003.

Author interview, Clyde Prestowitz, Economic Strategy Institute, July 28, 2003.

Author interview, Eric Alterman, Center for American Progress, November 21, 2003.

Author interview, Mark Agrast, Center for American Progress, July 27, 2004.

Author interview, Jody Clarke, Competitive Enterprise Institute, December 16, 2003.

A striking symbol of this shift came in the 1990s, when the Brookings Institution, an organization once averse to news media attention, built an $800,000 television studio on its own premises. Author interviews, Stephen Hess, Brookings Institution, July 16, 2003; Ed Berkey, Brookings Institution, March 28, 2006.

Author interview, Alice Rivlin, Brookings Institution, February 11, 2004.

Author interview, Charles Kolb, Committee for Economic Development, November 26, 2003.

Author interview, David Boaz, Cato Institute, November 24, 2003.

Author interview, Bruce Stokes, National Journal and Council on Foreign Relations, June 30, 2003.

Author interview, Alice Rivlin, Brookings Institution, February 11, 2004.

Author interview, Fred Smith, Jr., Competitive Enterprise Institute, December 16, 2003.

Author interview, John Cavanagh, Institute for Policy Studies, August 26, 2003. On a similar note, Greg Anrig, vice president of the Century Foundation, explains: “It really is difficult to find somebody who is very smart and knowledgeable [and] who also is able to write effectively and clearly for people who aren’t experts and can talk to the media to provide sound bites.” Whereas academic scholars tend to be too narrow in their focus, “people from [Capitol] Hill...are more likely to have the skills to be able to communicate and talk in sound bites. The flip side of that, though, is the heft. They typically don’t have Ph.D’s, by and large. They haven’t developed an expertise beyond the ‘faster turnaround’ kind of stuff.” (Author interview, Greg Anrig, The Century Foundation, November 21, 2003)

The Washington Monthly, New Republic, and National Journal are all political magazines; “The Hotline” is the National Journal’s “blogometer,” a daily compendium of political web blogs (see http://blogometer.nationaljournal.com/, retrieved on July 31, 2006); “The West Wing” is a television series that aired on NBC from 1999 to 2006; “K Street” was a short-lived HBO television series that aired in 2003.

Author interview, Henry Aaron, Brookings Institution, November 19, 2003. Aaron referred to Brookings’ dual orientation to academic and political debates. He continued, “I would say the relative importance of the face looking toward the academic world has diminished. It’s uneven. We still put out a journal called Brookings Papers on Economic Activity...but little of the rest of the activities here by most of the staff aims toward, [or] would count favorably, if they were applying for a university job.”

Brookings Institution website, http://www.brookings.edu/index/aboutresearch.html, retrieved on May 24, 2007; American Enterprise Institution website, http://www.aei.org/about/filter.all/default.asp, retrieved on May 24, 2007.

My emphasis. Institute for Policy Studies website, http://www.ips-dc.org/overview.htm, retrieved on May 24, 2007.

Author interview, Eric Alterman, Center for American Progress, November 21, 2003.

Manhattan Institute website, http://www.manhattaninstitute.org/html/about_mi.htm, retrieved on May 24, 2007.

Author interview, Norm Ornstein, American Enterprise Institute, June 15, 2004.

Author interview, Adam Meyerson, Philanthropy Roundtable, March 16, 2004.

Author interview, David Boaz, Cato Institute, November 24, 2003.

Author interview, Dean Baker, Center for Economic and Policy Research, June 11, 2003.

Author interview, Norm Ornstein, American Enterprise Institute, June 15, 2004.

Author interview, Tim Ransdell, California Institute, July 21, 2003.

Author interview, William Galston, University of Maryland, June 3, 2004. Anti-tax activist Grover Norquist highlights the difference between academic and political temporalities in similar terms:

I: What are the marks of a good policy report?

GN: Timeliness. Legislation moves at certain times. A study of the impact of the French Revolution done at a university is interesting this year. It will be interesting in five years. A study on why a particular piece of legislation would be good or bad for the economy is only of interest in the context of the fact that the legislation is going to be discussed and voted on.

Author interview, Grover Norquist, Americans for Tax Reform, August 2, 2004.

Author interview, Mark Agrast, Center for American Progress, July 27, 2004.

Author interview, Greg Anrig, The Century Foundation, November 21, 2003.

Washington Post online chat, http://www.washingtonpost.com/, retrieved on September 14, 2004.

The Economist. 2006. “The Battle of Ideas.” May 23. See also Bai (2003), who characterizes the Heritage Foundation as “like a university unto itself.”

For a critique, see Medvetz (2011).

References

Abelson, D. E. (2002). Do think tanks matter?: Assessing the impact of public policy institutes. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

Bai, M. (2003). Notion building. New York Times Magazine. October 12, 82.

Brookings Institution. (2007). Brookings Institution Press spring 2007 catalogue. Washington: Brookings Institution.

Critchlow, D. T. (1985). The Brookings Institution, 1916–1952: Expertise and the public interest in a democratic society. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Domhoff, G. W. (1999). Who rules America? Power and politics in the year 2000. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Dye, T. R. (1978). Oligarchic tendencies in national policy-making: The role of the private policy-planning organizations. Journal of Politics, 40, 309–331.

Feulner, E. J. (Ed.). (1980). Mandate for leadership: Policy management in a conservative administration. Washington: Heritage Foundation.

Feulner, E. J., (Ed.) (1985). Ideas, think-tanks and governments. Quadrant, November, 22–26.

Hall, C. (1983). Outsider at the center: The contrary ways of Richard Dennis. Washington Post, June 29, B1.

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2003). Defeating Kyoto: The conservative movement’s impact on U.S. climate change policy. Social Problems, 50, 8–373.

Medvetz, T. (2011). Think tanks in America: Power, politics, and the rules of intellectual engagement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peschek, J. G. (1987). Policy-planning organizations: Elite agendas and America’s rightward turn. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Rich, A. (2004). Think tanks, public policy, and the politics of expertise. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rich, A. O., & Weaver, R. K. (1998). Advocates and analysts: Think tanks and the politicization of expertise. In A. J. Cigler & B. A. Loomis (Eds.), Interest group politics (5th ed., pp. 235–254). Washington: CQ.

Rich, A. O., & Weaver, R. K. (2000). Think tanks in the U.S. media. Press/Politics, 5, 81–103.

Rothenberg, R. (1987). The idea merchant. New York Times Magazine. May 3, 36.

Smith, J. A. (1991a). The idea brokers: Think tanks and the rise of the new policy elite. New York: Free.

Smith, J. A. (1991b). Brookings at seventy-five. Washington: Brookings Institution.

Tolchin, M. (1983). Brookings thinks about its future. New York Times, December 14, A30.

Wacquant, L. (2001). Whores, slaves and stallions: Languages of exploitation and accommodation among boxers. Body & Society, 7, 181–194.

Weaver, R. K. (1989). The changing world of think tanks. PS: Political Science and Politics, September, 563–578.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by awards from the Social Science Research Council’s Fellowship Program on Philanthropy and the Nonprofit Sector, the National Science Foundation (Dissertation Improvement Grant #0526199), the Phi Beta Kappa Society, Alpha Chapter, and the University of California, Berkeley Graduate Division. The author is grateful to Jerome Karabel, Loïc Wacquant, Gil Eyal, Charles Camic, Stephanie Mudge, Malcolm Fairbrother, the members of Neil Fligstein’s Center on Culture, Organizations, and Politics, and the anonymous reviewers of Qualitative Sociology for their helpful comments.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

*The title and main theme of this paper recall Wacquant (2001).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Medvetz, T. “Public Policy is Like Having a Vaudeville Act”: Languages of Duty and Difference among Think Tank-Affiliated Policy Experts. Qual Sociol 33, 549–562 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-010-9166-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-010-9166-9