Abstract

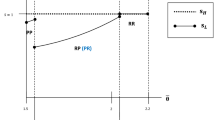

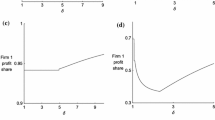

In this paper, we extend the Varian (1980) model to examine endogenous quality differentiation by firms, with a particular emphasis on the interplay between the firms’ product quality decisions and the ensuing price rivalry. Specifically, we assume that the price-sensitive (or informed) consumers hold a lower valuation for product quality than the brand-loyal (or uninformed) consumers. It is shown that the firms will choose differentiated qualities for a broad class of consumer utility functions and production technologies. We obtain two results. First, the equilibrium quality choices are efficient as they are also the welfare-maximizing qualities chosen by a social planner. The equilibrium qualities are as if one firm serves only its loyal consumers and the other serves only the price-sensitive consumers, even though they each serve both types of consumers (at least for some fraction of time). Second, the firm choosing the lower quality makes greater profits and also prices more aggressively, in the sense that it maintains a lower maximum price and offers discounts more often. The lower-quality product is more profitable because it yields higher social surplus when consumed by the price-sensitive consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank an anonymous referee (Referee 1) for providing the second interpretation.

For empirical evidence on price dispersion, see, for example, Villas-Boas (1995), Brynjofsson and Smith (2000), Chevalier and Goolsbee (2003).

In models of advertising consumers may also differ in the number of ads received (e.g., Butters, 1977; Robert and Stahl, 1993; McAfee, 1994; McGahan and Ghamawat, 1994).

Just like (Raju et al., 1990; Rao, 1991) also considers a duopoly with asymmetric consumer loyalty, but with the magnitude of loyalty following a continuous, rather than discrete, distribution.

In the price equilibrium below, the probability of such a tie is zero.

We thank an anonymous referee (Referee 2) for noting this point.

The firms’ quality choices according to the profit functions in case (2) of Proposition 1 are given by \(c^{\prime}(s_{H}^{\ast})=u_{2}( \theta_{1},s_{H}^{\ast})\) and \(c^{\prime}(s_{L}^{\ast})=u_{2}( \theta_{2},s_{L}^{\ast})\). Because \(\theta _{1}<\theta_{2}\) and \(u_{12}>0\) by assumption, we have \(s_{H}^{\ast}<s_{L}^{\ast}\), contradicting the presumption of Proposition 1 that firm 1's quality is equal to or higher than that of firm 2. The quality choices according to the profit functions in case (3) of Proposition 1 are given by \(c^{\prime}(s_{H}^{\ast})=u_{2}( \theta_{2},s_{H}^{\ast})\) and \(c^{\prime }(s_{L}^{\ast})=u_{2}(\theta_{2},s_{L}^{\ast})\). Hence, \(s_{H}^{ \ast}=s_{L}^{\ast}\). However, either firm benefits by deviating to a lower quality \(s_{L}^{{}}\) characterized by \(c^{\prime}(s_{L}^{{}})=u_{2}( \theta_{1},s_{L}^{{}})\). Therefore, cases (2) and (3) of Proposition 1 can never arise in the subgame perfect equilibrium.

References

Anderson, S. P., & Renault, R. (1999). Pricing, product diversity, and search costs: A Bertrand-Chamberlin-Diamond model. RAND Journal of Economics, 30, 719–735.

Allenby, G., & Rossi, P. (1991). Quality perceptions and asymmetric switching between brands. Marketing Science, 10, 185–204.

Bakos, Y. (1997). Reducing buyer search costs: Implications for electronic marketplaces. Management Science, 43, 1676–1692.

Baye, M. R., & Morgan, J. (2001). Information gatekeepers on the internet and the competitiveness of homogeneous product markets. American Economic Review, 91, 454–474.

Bergen, M., Dutta, S., & Shugan, S. M. (1996). Branded variants: A retail perspective. Journal of Marketing Research, 33, 9–19.

Blattberg, R., & Neslin, S. (1990). Sales promotion concepts, methods, and strategies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Smith, M. (2000). Frictionless commerce? A comparison of internet and conventional retailers. Management Science, 46, 563–585.

Butters, G. R. (1977). Equilibrium distributions of sales and advertising prices. Review of Economic Studies, 44, 465–491.

Chen, Y., Narasimhan, C., & Zhang, J.Z. (2001). Consumer heterogeneity and competitive price-matching guarantees. Marketing Science, 20, 300–314.

Chen, Y., Iyer, G., & Padmanabhan, V. (2002). Referral infomediaries. Marketing Science, 21, 412–434.

Chevalier, J., & Goolsbee, A. (2003). Measuring prices and price competition Online: Amazon.com and BarnesandNoble.com. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 1, 203–222.

Davis, S., Murphy, K. M., & Topel, R. (2004). Entry, pricing, and product design in an initially monopolized market. Journal of Political Economy, 112, S188–S225.

Diamond, P. (1987). Consumer differences and prices in a search model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102, 429–436.

Erdem, T., Imai, S., & Keane, M. (2003). Brand and quality choice dynamics under price uncertainty. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 1, 5–64.

Gal-Or, E. (1983). Quality and quantity competition. Bell Journal of Economics, 14, 590–600.

Grossman, G. M., & Shapiro, C. (1984). Informative advertising with product differentiation. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 63–81.

Hann, I.-H., Hui, K.-L., Lee, S.-Y. T., & Png, I. P. L. (2005). Sales and promotions: A more general model. Working Paper, National University of Singapore.

Iyer, G., & Pazgal, A. (2003). Internet shopping agents: Virtual co-location and competition. Marketing Science, 22, 85–106.

Kiser, E. (1998). Heterogeneity in price sensitivity and retail price discrimination. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 80, 1150–1153.

Kuksov, D. (2004). Buyer search costs and endogenous product design. Marketing Science, 23, 490–499.

Lal, R., & Matutes, C. (1989). Price competition in multimarket duopolies. RAND Journal of Economics, 20, 516–537.

Lal, R., & Villas-Boas, J. M. (1996). Exclusive dealing and price promotions. Journal of Business, 69, 159–172.

Lal, R., & Villas-Boas, J. M. (1998). Price promotions and trade deals with multiproduct retailers. Management Science, 44, 935–949.

Lehmann-Grube, U. (1997). Strategic choice of quality when quality is costly: The persistence of the high-quality advantage. RAND Journal of Economics, 28, 372–384.

Lynch, J. G., & Ariely, D. (2000). Wine online: Search costs affect competition on price, quality, and distribution. Marketing Science, 19, 83–103.

McAfee, R. P. (1994). Endogenous availability, cartels, and merger in an equilibrium price dispersion. Journal of Economic Theory, 62, 24–47.

McGahan A. M., & Ghemawat, P. (1994). Competition to retain customers. Marketing Science, 13, 165–176.

Mehta, N., Rajiv, S., & Srinivasan, K. (2003). Price uncertainty and consumer search: A structural model of consideration set formation. Marketing Science, 22, 58–84.

Moorthy, S. (1988). Product and price competition in a duopoly. Marketing Science, 7, 141–168.

Mussa, M., & Rosen, S. (1978). Monopoly and product quality. Journal of Economic Theory, 18, 301–317.

Narasimhan, C. (1988). Competitive promotional strategies. Journal of Business, 61, 427–449.

Png, I. P. L., & Hirshleifer, D. (1987). Price discrimination through offers to match price. Journal of Business, 60, 365–383.

Raju, J. S., Srinivasan, V., & Lal, R. (1990). The effects of brand loyalty on competitive price promotional strategies. Management Science, 36, 276–304.

Rao, R. (1991). Pricing and promotions in asymmetric duopolies. Marketing Science, 10, 131–144.

Robert, J., & Stahl II, D. O. (1993). Informative price advertising in a sequential search model. Econometrica, 61, 657–686.

Rosenthal, R. W. (1980). A model in which an increase in the number of sellers leads to a higher price. Econometrica, 48, 1575–1580.

Salop, S., & Stiglitz, J. (1977). Bargains and Ripoffs: A model of monopolistically competitive price dispersion. Review of Economic Studies, 44, 493–510.

Shaffer, G., & Zhang, J. (2002). Competitive one-to-one promotions. Management Science, 48, 1143–1160.

Shaked, A., & Sutton, J. (1982). Relaxing price competition through product differentiation. Review of Economic Studies, 49, 3–13.

Shilony, Y. (1977). Mixed pricing in oliogopoly. Journal of Political Economy, 14, 373–388.

Sobel, J. (1984). The timing of sales. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 353–368.

Stahl II, D. O. (1989). Oligopolistic pricing with sequential consumer search. American Economic Review, 79, 700–712.

Sun, B., Neslin, S., & Srinivasan, K. (2003). Measuring the impact of promotions on brand switching when consumers are forward looking. Journal of Marketing Research, 40, 389–405.

Tellis, G., & Wernerfelt, B. (1987). Competitive price and quality under asymmetric information. Marketing Science, 6, 240–253.

Varian, H. (1980). A model of sales. American Economic Review, 70, 651–659.

Villas-Boas, J. M. (1995). Models of competitive price promotions: Some empirical evidence from the coffee and saltine crackers markets. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 4, 85–107.

Villas-Boas, J. M., & Schmidt-Mohr, U. (1999). Oligopoly with asymmetric information: Differentiation in credit markets. RAND Journal of Economics, 30, 375–396.

Wernerfelt, B. (1994). Selling formats for search goods. Marketing Science, 13, 298–309.

Wolinsky, A. (1984). Product differentiation with imperfect information. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 53–61.

Wu, J., & Rangaswamy, A. (2003). A fuzzy set model of search and consideration with an application to an online market. Marketing Science, 22, 411–434.

Zettelmeyer, F. (2000). Expanding to the internet: Pricing and communications strategies when firms compete on multiple channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 37, 292–308.

Zwick, R., Rapoport, A., Lo, A., King, C., & Muthukrishnan, A. V. (2003). Consumer sequential search: Not enough or too much? Marketing Science, 22, 503–519.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank two referees for their insightful comments and the Editor, Rajiv Lal, for his encouraging remarks. Useful feedback was also received from the participants in a seminar at New York University and the 2006 Midwest Economic Theory conference, especially Jay P. Choi. Any remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

JEL classifications D83 · L13 · M31

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jing, B. Product differentiation under imperfect information: When does offering a lower quality pay?. Quant Market Econ 5, 35–61 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-006-9014-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-006-9014-0