Abstract

Interpersonal networks facilitate business cooperation and socioeconomic exchange. But how can outsiders demonstrate their trustworthiness to join existing networks? Focusing on the puzzling yet common phenomenon of heavy drinking at China’s business banquets, we argue that this costly practice can be a rational strategy intentionally used by entrants to signal trustworthiness to potential business partners. Because drinking alcohol can lower one’s inhibitions and reveal one’s true self, entrants intentionally drink heavily to show that they have nothing to hide and signal their sincere commitment to cooperation. This signaling effect is enhanced if the entrants have low alcohol tolerance, as their physical reactions to alcohol (e.g., red face) make their drunkenness easier to verify. Our theory of heavy social drinking is substantiated by both ethnographic fieldwork and a discrete-choice experiment on Chinese entrepreneurs. This research illuminates how trust can be built absent sufficient support from formal institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Economic activities are embedded in social networks (Aoki, 2001; Granovetter, 1985), which facilitate cooperation and business by enabling repeated interactions and constraining cheating. This is especially important when formal institutions such as the politico-legal system fail to protect property rights and ensure efficient resource distribution (Chang, 2011; Clay, 1997; Greif, 2006; Kali, 1999; Richman, 2017). However, outsiders may find it difficult to join existing networks. Not knowing outsiders’ credibility, incumbents might hesitate to cooperate with them, despite the potential benefits (Seabright, 2010). How do the two sides overcome the trust barrier? An emerging body of research has found that by investing in credible, often costly, signals, outsiders can make their favorable but unobservable characteristics, such as trustworthiness and cooperativeness, known to potential partners and distinguish themselves from cheaters (Bereczkei et al., 2010; Camerer, 1988; Gambetta & Székely, 2014; Gintis et al., 2001; Gurven et al., 2000; Leeson, 2008, 2014a; Posner, 1998, 2009; Skarbek & Wang, 2015). Substantiated by evidence from China, this paper argues that, in some cultural circumstances, the puzzling yet common practice of heavy drinking when doing business in China allows outsiders to signal trustworthiness so as to join existing business networks.

Drinking is widely considered to bear symbolic and ritual meaning that promotes socioeconomic cooperation (Adler, 1991; Barrows & Room, 1991; Fuller, 1995; Heath, 2000; Sherratt, 2014). For example, wedding toasts acknowledge the newlyweds’ new status (Chrzan, 2013), and after-work drinking communicates patterns of work and leisure (Gusfield, 1987; Moeran, 2021). Recent studies have also examined the chemical effects of alcohol on economic behaviors. Some research finds that alcohol might make a drinker more aggressive, fallible, and impatient (Corazzini et al., 2015; Schweitzer & Gomberg, 2001), and other research shows that moderate social drinking can promote cooperation and bonding because it relaxes the drinker, lowers their social inhibitions, leads to displays of emotion (in facial expression and speech), and facilitates truth telling, as in the ancient Roman proverb “In vino veritas” (Au & Zhang, 2016; Peters & Stringham, 2006; Sayette et al., 2012). Slingerland (2021) demonstrated from an evolutionary perspective that despite huge health and social costs, alcohol fosters creativity and solidarity, contributing to its prevalence since ancient times. Haucap and Herr (2014), from a rational choice perspective, explained how alcohol can be used socially to help drinkers network, especially those who enjoy drinking.

Insightful as they are, however, existing studies have mainly focused on moderate alcohol consumption. An explanation is still lacking for the rationale for heavy drinking in some business settings, especially when it comes to individuals who do not enjoy or have low alcohol tolerance. Drinking at lavish banquets is nearly indispensable when doing business in China and is particularly common when businesspeople try to establish a network with potential cooperators. High-end Chinese liquors (baijiu—e.g., Maotai [茅台]), which are often much stronger than other types of alcohol, are popular at such banquets (Hurun Report, 2019). Moreover, participants in banquets often drink heavily and suffer hangovers, even though many of them do not enjoy drinking. A survey of more than 3,600 adults in China revealed that 68.5% of respondents considered drinking at banquets tormenting (Lin, 2022a).

We argue that in this circumstance, drinking is not only a ritual for launching business deals but a signaling strategy that businesspeople employ to demonstrate trustworthiness and establish interpersonal networks, or guanxi. Building upon existing works, especially Haucap and Herr (2014) and Slingerland (2021), we argue that because alcohol can lower the drinker’s guard, leading to (unwilling) truth telling, only trustworthy entrants will intentionally drink so heavily as to lose control of themselves. The effectiveness of heavy social drinking as a signal of trustworthiness depends on the ability of signal receivers to verify the sender’s drunkenness. Since people can easily fake being drunk, receivers might require the sender to disclose their intake of alcohol. The receivers can also rely on involuntary reactions to alcohol intoxication, such as physiological responses that are hard to fake.

We substantiate our theory using mixed methods. First, we conduct intensive ethnographic fieldwork. Banquet norms gleaned from field observations and interviews support our theory that banquet hosts, who are network entrants, drink heavily to signal trustworthiness to their guests, who are potential partners. Second, we test the propositions through a discrete-choice experiment (DCE) on Chinese entrepreneurs with extensive experience of drinking at banquets. To test for treatment effects, the respondents are randomized into groups and picked ideal business partners from pairs of candidates with different attributes. The experimental results largely confirm our propositions.

Our paper contributes to the literature on institutional mechanisms and networking strategies deployed to secure cooperation. We show that in addition to widely employed strategies to establish trustworthiness—such as posting a hostage, paying a deposit, and sharing compromising information (Gambetta & Przepiorka, 2019; Werner & Keren, 1993)—drinking alcohol, a conduit unnoticed by prior research, can also be used by outsiders to signal trustworthiness and join existing networks. Therefore, we offer a rational choice account of heavy drinking that is prevalent in some social circumstances and appears to be painful and wasteful. In doing so, our research also contributes to the growing public choice literature, pioneered by Peter Leeson, which seeks to rationalize puzzling and seemingly unproductive institutions and social practices such as human sacrifice, Gypsy Law, ordeals, oracles, witch trials, and child brides (e.g., Leeson, 2012, 2013, 2014a, bb, Leeson, 2014c; Leeson & Russ, 2018; Leeson & Suarez, 2017; see also Maltsev, 2022a, b on sects in Russia).

By integrating social anthropology and institutional economics, our paper also contributes to the broad literature on the economic rationality underlying everyday symbolic and customary practices (e.g., food sharing, gift and charitable giving, and ceremonies) that exist (partially) because they promote cooperation (Bird et al., 1997; Bird et al., 2002; Bénabou & Tirole, 2006; Bracha & Vesterlund, 2017; Carmichael, 1997; Carr & Landa, 1983; Chwe, 2013; Glazer & Konrad, 1996; Skarbek & Wang, 2015; Yan, 1996; Yang, 1994). Finally, we broaden the scope of signaling theory to more social scenarios by looking at the banquets as a signaling game and showing that the signaling is a powerful commitment device that can promote trust and cooperation (Bereczkei et al., 2010; Gambetta & Székely, 2014; Gintis et al., 2001; Leeson, 2008; Posner, 1998; Sosis et al., 2007; Van der Weele, 2012).

2 A theory of heavy social drinking

Interpersonal networks are frequently relied upon for doing business in transitional economies because such economies’ formal institutions suffer major shortcomings. First, in such economies, weak rule of law can hinder the making and enforcement of contracts that ensure every party fulfills their duties and receives their benefits. For instance, the judicial system in China has suffered from being subject to the political influence of government officials and the ruling party, lacking professionalism and accountability, receiving inadequate funding, and being conducive to judges’ corruption (Gong, 2004; Wang, 2013). Courts also lack coercive tools to enforce civil judgments. These deficiencies can greatly undermine judicial fairness, increase the cost and uncertainty of litigation, and decrease judicial efficiency and reliability (Clarke, 1996; Gong, 2004; Peerenboom, 2002). Second, traditional culture may exacerbate the problem by dampening people’s willingness to use courts. For example, Chinese people, including businesspeople, tend to believe that litigation can damage their reputation.Footnote 1 Third, in transitional economies, resources (e.g., land and other scarce natural resources) and business opportunities are often controlled by the government and directed at cronies (Harber et al., 2003, Ruan & Wang, 2023; Zhan, 2022; Zhu, 2012). Consequently, businesspeople depend heavily on personal connections to conduct business with those deemed trustworthy and to access scarce resources.

In China, guanxi, or interpersonal networks, is a common private cooperation mechanism sustained by reputation and reciprocity (Burt & Burzynska, 2017; Chang, 2011; Kiong & Kee, 1998). It serves to coordinate people’s beliefs about how others will respond and enables them to communicate about their resources and past behaviors (Wang, 2014; Zhan, 2012). Individuals’ misbehaviors that could damage their reputation—such as free riding, fraud, and contract violations—can be greatly discouraged by guanxi because being perceived as untrustworthy can cause one to be ostracized and lose the long-term benefits of guanxi. Thus, guanxi reduces transaction costs for network incumbents and reinforces the pattern of repeated exchange of favors by mitigating opportunism (Hwang, 1987; Standifird & Marshall, 2000). Having guanxi with politically and economically powerful network members also confers privileges and facilitates favor seeking (Su & Littlefield, 2001). Therefore, it plays an important role in establishing, enabling, and sustaining long-term business cooperation.

However, guanxi does not create itself. When businesspeople make a deal, they often need to first establish guanxi with potential partners in an existing network. But potential partners may lack information about entrants’ past behaviors and find it difficult to evaluate the entrants’ trustworthiness. Evaluation can be especially difficult when the economy expands and socially distant outsiders with no reputation try to join a network (Landa, 1994). Cooperating with a deceiver can bring losses to network incumbents. The risk is typically high when the exchanges are nonsimultaneous, which means incumbents must commit resources (e.g., making payments) before the entrants return benefits, or when the cooperation involves illegal transactions (e.g., corruption or the production or exchange of illegal products) that are not protected by formal enforcement mechanisms and can elicit legal sanctions (Li, 2011).

To solve the asymmetric information problem, cooperative entrants may signal their trustworthiness, a trait that supports long-term cooperation but is not readily observable, to potential partners. Trust, as defined by Rotter (1967, p. 65), is a “generalized expectancy held by an individual that the word, promise, oral or written statement of another individual or group can be relied on.” Trustworthiness generally indicates one’s reliability such as their willingness to keep promises (instead of deceiving or cheating) and cooperate despite having to endure hardship or bear other costs (Cook et al., 2005). Thus, potential partners prefer to enter into contracts with and maintain long-term cooperation with entrants they perceive as trustworthy.

Signaling is widespread in market and nonmarket environments. It is used to deter attackers or competitors, enhance status, and facilitate solidarity and cooperation. For instance, investing in rituals or religious commitment can increase trust both within and across groups and promote cooperation (Hall et al., 2015; Soler, 2012).Footnote 2 A credible signal requires senders to take an action that dishonest mimickers are unwilling to perform. In some scenarios, receivers can readily determine that signals are costly—for example, if the signal requires the sender to behave violently—while in other scenarios, receivers must rely on subtle clues, such as facial expressions or emotional responses, to evaluate the signals’ costliness (Bird & Smith, 2005; Cheng et al., 2020; Ohtsubo & Watanabe, 2009; Soler, 2012; Sterelny & Hiscock, 2014).

Credible signaling can demonstrate entrants’ willingness to build network ties with potential partners (Leeson, 2008). In China, gift giving governs daily life in communities and commerce (Bulte et al., 2018; Camerer, 1988; Cao et al., 2020; Steidlmeier, 1999; Yan, 1996). As Posner (2009) explained, a good gift shows the giver’s willingness to maintain a reciprocal long-term relationship with the receiver because the relationship must endure for a long time before the giver can recover their investment (e.g., the money and time required to acquire goods). Heavy drinking at Chinese business banquets is another significant, prevalent, and understudied signaling mechanism that can help entrants (signal senders, who are often banquet hosts) show potential partners (signal receivers, who are network incumbents and often banquet guests)Footnote 3 their trustworthiness, which gift giving alone cannot.

Unlike with gift giving, the cost of heavy drinking lies not only in money and time but in harming one’s healthFootnote 4 and, more importantly, revealing one’s true intentions after the drinking lowers their guard. Medical research has shown that by targeting drinkers’ prefrontal cortex, which is the center of cognitive control and behavioral direction, alcohol can slow their reflexes and dull their senses. Hence, large amounts of alcohol can weaken drinkers’ capacity to maintain a clear sense of defense, control their behavior (including hiding their intentions), and stay focused on tasks, which is unlikely without alcohol (Slingerland, 2021). Therefore, by drinking heavily, often to the point of losing consciousness and suffering considerable physical discomfort, entrants show that they are not afraid to tell the truth and that they will overcome hardship to fulfill their promises (e.g., the promise to drink).

Truth telling under the influence of alcohol is acceptable for entrants who sincerely want to sustain long-term cooperation, as revealing the truth after putting down their guard will not call into question their trustworthiness. However, the cost of truth telling can be unaffordable for cheaters because heavy drinking can hinder them from disguising their true intentions and lead them to reveal their ulterior motives, which makes cooperation impossible. In brief, heavy drinking can be a credible trustworthiness-signaling mechanism if it creates a cost differential between trustworthy entrants and cheaters .

Proposition 1

Signaling effect of heavy drinking: heavy drinking can signal entrants’ trustworthiness as cooperators.

Proposition 2

Cooperation outcome of heavy drinking: heavy drinking can help entrants establish long-term guanxi with potential partners.

However, because people have different levels of tolerance of alcohol, some entrants with high alcohol tolerance might be able to fake being drunk. Only when the potential partners, or signal receivers, can confirm that the entrants have drunk to the point of (nearly) getting intoxicated and losing control will they be confident that the entrants are revealing their true selves. Thus, signal receivers need the senders to reveal their intake of alcohol; involuntary reactions to intoxication by alcohol, which are hard to fake, help the potential partners verify the entrants’ drunkenness.

A condition caused by aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) deficiency, the alcohol flush reaction, in which one’s face turns red after drinking alcohol, is one indicator of relatively low alcohol tolerance that can be read to verify drunkenness. People with low alcohol tolerance often develop flushes or blotches associated with erythema on their face and neck after drinking (Brooks et al., 2009). The condition is fairly common among Asians and is often associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer in those who drink (Lee et al., 2008, 2014). This distinctive and visible sign probably accounts for why heavy drinking as a trust device is more common in China than in non-Asian transitional economies.

Proposition 3

Heterogeneous effect of alcohol (in)tolerance: entrants with low alcohol tolerance (red face) who drink heavily are more likely to establish guanxi with potential partners.

In Online Appendix A, we develop game-theoretic signaling models of drinking to capture the strategic interaction between an entrant (signal sender) and a potential partner (signal receiver).Footnote 5

3 Alcohol and alliance: drinking to signal trustworthiness at China’s business banquets

To substantiate our theory of heavy social drinking, we conducted ethnographic fieldwork in the provinces of Guangdong, Jiangxi, and Hebei from 2021 to 2024. We conducted observations at 20 business banquets as both participants and nonparticipants. Attending the banquets and observing their organization and procedures helped us understand the norms regulating the signaling practices of heavy drinking. We also interviewed 14 frequent banquet participants. Because a guest at one banquet is often a host at another one, these interviewees were able to convey their views about heavy social drinking from the perspectives of both signal senders and receivers.

Being entryways to guanxi, China’s lavish business banquets are organized with remarkable intricacy and “considerable calculations” (Bian, 2001, p. 281; Bian, 2019; Hessler, 2006). We found that although banquets sometimes appear informal, they are serious occasions on which entrants try hard to make a favorable impression. Banquet hosts, who are usually the entrants into a business network, provide guests, who are the potential business partners, with hospitality in the form of a delicious meal, extravagant alcohol, and dedicated service. Banquets often occur in quasi-public spaces, such as private rooms in restaurants in which participants are clearly separated from nonparticipants. The restaurants and private rooms are high-end and handpicked by the hosts to demonstrate respect for the guests. Many private rooms nowadays are well furnished and equipped with a small kitchen and restroom for customers’ convenience. Banquet participants usually sit at a round table, with the main host sitting facing the door, indicating that they are paying for the banquet. The main guest often sits to the host’s left, indicating their high status and importance among the participants. Other participants sit on both sides of the main host and main guests according to their seniority or status in the network.

Alcohol and drinking are in the spotlight at the banquet. High-end and high-alcohol liquors such as Maotai with 53% alcohol by volume have come to symbolize prestige and opulent business entertainment in China. The high demand for Maotai is evident in the product’s premium price and the company’s substantial market capitalization. The price of Maotai increased from approximately US$150 in 2014 to US$420 in 2023 per 500 mL bottle (Sina, 2019).Footnote 6 Several interviewees mentioned that hosts always ensure the supply of alcohol lasts until the conclusion of the banquet.

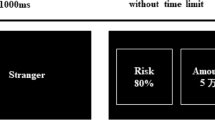

Hosts are expected to indulge in heavy drinking in a highly ritualized manner. This ritualization seems aimed to make it easier for guests to measure hosts’ alcohol consumption. To that end, the alcohol, glasses, and liquor dividers are selected, prepared, and regulated in accordance with unwritten rules. Everyone is given a transparent 10 mL glass (large enough to hold a single slug of alcohol) and a liquor divider (which allows people to serve themselves and, more importantly, to measure the amount they drink; Fig. 1). In areas where people have high alcohol tolerance on average (or people tend to drink more—e.g., Shandong Province), 165 mL glasses are used and people are expected to finish them with three to four gulps (Sohu, 2013). Banquet participants who prefer to drink wine and beer might be expected to drink three and six times more than those who drink liquor, respectively.

Hosts are expected to drink at several key moments of the banquet, always in a very visible way. The host usually starts the banquet by thanking the guests for coming and proposing that everyone participate in three toasts together. In this initial round, all participants drink. After the toasts, the entrant can walk around the table to drink and network with individual guests. The host toasts the main guest first and then the other guests according to their seniority or status, paying tribute to them and demonstrating sincerity and strong interest in cooperating with them. The host keeps their glass lower than a guest’s glass when the two clink glasses, symbolizing their humble position and respect for the guest.

At these banquets, drinking is not just for fun, a fact that is acknowledged by their participants. After clinking glasses, the host often tells a guest, “I will drink up, and you don’t have to [wo gan nin sui yi].” As one interviewee told us, saying that means “I am prepared to bear the suffering to make our cooperation work while no pressure is placed on you.”Footnote 7 Another interviewee interpreted drinking in this circumstance as a way of acting on the Chinese proverb “I would go through fire and water without hesitation for our business cooperation.”Footnote 8 After drinking, the host often raises their glass slightly to let others witness that they drank as promised. After toasting and drinking with every guest once, the host often toasts important guests in several additional rounds.

Drinking is also used as self-punishment by the host and sometimes as a test given by potential partners, creating more opportunities to drink visibly. For example, when a host realizes that they are behaving uncourteously, such as answering a phone call when dining (even for an emergency), they often drink three glasses of alcohol continuously under the gaze of other participants as self-punishment. This act often wins other participants’ applause, which indicates that they not only have forgiven the misbehavior but appreciate the host’s sincerity. Sometimes potential partners make a conditional offer: they will do business with or give business opportunities to the host if the latter drinks a certain amount of alcohol in one shot, such as 250 mL of Chinese liquor.Footnote 9 These rites allow potential partners (signal receivers) to observe the hosts’ alcohol intake.

As the drinking proceeds, participants feel more relaxed and open to conversation. On many occasions, after heavy drinking, participants start to share their personal stories, and some might start to sing or dance. When asked why entrants have to drink to that extent, an interviewee explained that “drinking gives the feeling of dizziness and disorientation, making people speak out their heartfelt words and behave as who they really are.”Footnote 10 Another interviewee held a similar view: “Alcohol is a catalyst; individuals become more talkative only when they consume a substantial amount.”Footnote 11

Hosts often end up drinking a large amount, which is physically painful. An interviewee with extensive banquet experience even likened alcohol to a poison that erodes one’s gut.Footnote 12 However, when asked whether it is possible to avoid heavy drinking, an interviewee reported that “simply giving gifts might not substitute for drinking because many networks are established at banquets.”Footnote 13 Another interviewee said, “Playing tricks at banquets is absolutely not allowed because drinking shows sincerity and not drinking would be perceived as dishonest, untrustworthy, and even silly.”Footnote 14

The host must not unilaterally end the banquet; otherwise, they will be seen as not sincere or dedicated to business cooperation. Thus, drinking often continues until the most important guest suggests all participants conclude the banquet with a final glass of alcohol. Some hosts, as explained by an interviewee, “might go to toilets to vomit every once in a while to avoid getting heavily drunk too early.”Footnote 15 It is not surprising that some hosts get very drunk by the end and even experience alcohol poisoning.Footnote 16 The pressing need to drink also forced some interviewees who were allergic to alcohol to leave their sales and marketing posts to avoid these circumstances to avoid these circumstances.Footnote 17 Entrants from areas where people drink less often inevitably drink much more when they do business in areas with a higher average alcohol intake. Sometimes, foreigners who want to do business in China also need to follow local drinking rules as one interviewee working in international trade explained.Footnote 18

Thus, in general, as stated in Propositions 1 and 2, hosts who sincerely want to cooperate with potential partners treat heavy drinking as a necessary means to demonstrate that they have nothing to hide. Hosts who refrain from drinking heavily at such banquets are treated with diffidence. As one interviewee remarked, “One’s character while drinking reflects their true character.”Footnote 19

Heavy drinking’s ability to serve as a credible signal depends crucially on the host’s alcohol tolerance. When asked whether some people can fake drunkenness, an interviewee replied, “How much is considered a lot to drink also depends on one’s alcohol tolerance; it is common knowledge that those whose face easily becomes red after drinking at banquets have low alcohol tolerance.”Footnote 20 Another interviewee remarked, “At the banquets with new potential business partners, we tend to think that individuals whose faces turn red must have drunk to nearly their full capacity and tend to put more trust in such individuals.”Footnote 21 Therefore, a drinker’s red face is widely considered as a visible sign of intoxication, suggesting that they are unlikely to be faking drunkenness and hiding ulterior motives. Consistent with Proposition 3, this physical reaction makes trustworthy entrants even more distinguishable through heavy drinking.

In summary, drinking to the point of suffering and drunkenness is a means for entrants to demonstrate their trustworthiness. The logic resembles that of the rituals often associated with criminal-gang initiation practices, which help “elicit important information about a recruit’s ability and dedication” (Skarbek & Wang, 2015, p. 295).

4 Discrete-choice experiments

4.1 Experimental design

To further test our propositions, we designed a survey with a DCE from the potential partners’ perspectives to examine their responses to entrants’ signals. DCEs are also called conjoint experiments in some social science studies (Mares & Visconti, 2020; Tsai et al., 2022), although the two concepts are slightly different in economics (Louviere et al., 2010). Unlike the stated-preference survey method, which directly asks people’s opinions on each attribute, the DCE design allows respondents to choose their preferred profile from several candidate profiles. This experimental method is good for testing multidimensional preferences and estimating the causal effects of multiple attributes on hypothetical choices or evaluations (Bansak et al., 2021). By mimicking potential partners’ decision-making processes, a DCE can capture the difference between preferences and final decisions, which is difficult for stated-preference surveys to accomplish (Diamond & Hausman, 1994). The DCE design also helps to reduce social desirability bias because respondents need not express approval for controversial actions such as heavy drinking.

4.1.1 Participants

Given that our focus is on business cooperation, we used a focus group sampled from the business community in China to increase the external validity of our survey experiment. We distributed the survey to two local commercial associations from the provinces of Guangdong and Jiangxi. The head of each association promoted the survey during a gathering and then distributed the questionnaire on members’ social networking app (WeChat). The questionnaires were distributed to respondents in August 2021, and 272 of the 320 respondents completed the survey, for a response rate of 85%. The respondents were either entrepreneurs or salespersons at different-sized enterprises in different industries (see Online Appendix B). Thus, they were familiar with the decision-making context of the questions, and their responses represented a wide range of Chinese businesspeople.

4.1.2 Procedure

In the questionnaire, the respondents were presented with a short description of the context:

Agency A wants Agency B’s help and support for Project (A) The project was somewhat good but not necessary for Agency (B) The representatives of Agency A invited representatives of Agency B to a dinner banquet. At the banquet, they first drank three toasts to all participants and then had a good conversation.

As the banquet scenario proceeded in the survey, our respondents were asked to think of themselves as the leading representative of Agency B (the guest and potential partner) and were presented with two profiles of the representatives of Agency A (the hosts and entrants). Two attributes, drinking effort and alcohol tolerance, were included in the Agency A representatives’ profiles to test our three propositions. Given the prominence of Maotai in Chinese business banquets, we also included as an additional attribute the liquor brand. Thus, each profile featured three attributes whose values were assigned and ordered randomly to ensure no profile-order effect. With the randomized design, the respondents were exposed to 1 of 56 combinations with equal odds. The attributes were as follows:

Attribute 1: Drinking effort (Propositions 1 and 2): drinking a glass of alcohol with every attendee from Agency B (heavy drinking) versus drinking a total of two glasses (token gesture).

Attribute 2: Alcohol tolerance (Proposition 3): looks no different after heavy drinking (high alcohol tolerance), or exhibits red face and vomits in the restroom after heavy drinking (low alcohol tolerance).

Attribute 3: Liquor brand (Maotai’s role): Maotai (luxury liquor) versus Jian Nan Chun (good ordinary liquor).

For attribute 1, we used the Chinese term datongguan to describe drinking a glass of liquor with every attendee from Agency B—that is, heavy drinking by the entrant. Such a practice is widespread in our ethnographic observations and was mentioned by several interviewees.Footnote 22 People with experience with Chinese banquets, such as the respondents, all understand this term. Consider the case in which five guests from Agency B attend the banquet. In just one round of datongguan, the leading representative of Agency A would need to drink at least five (small) glasses, or 50 mL, of high-alcohol liquor. Adding that to the first three toasts that everyone drinks, the representative of Agency A would drink 80 mL. If there were more guests and more rounds of datongguan, the amount of alcohol drunk by the leading representative of Agency A could multiply several times. The two-glass alternative is widely considered a token gesture.

Attribute 2 differentiated the entrants’ alcohol tolerance. As discussed previously, red face is a good proxy for low alcohol tolerance. Our proposition predicts that a flushed face after heavy drinking will strengthen the signaling effect of heavy drinking, making the guests think that the entrants are trustworthy. Thus, we examine the heterogeneous treatment effect of red face conditional on different levels of drinking (attribute 1: heavy versus light) to test the effect of alcohol tolerance on cooperation (Proposition 3).

Attribute 3 contrasts Maotai, the most prized liquor (costing more than RMB 3,000 per bottle) with Jian Nan Chun (剑南春), a common good liquor for banquets (RMB 1,000 per bottle), to explore the role of Maotai in the signaling game. Online Appendix C provides details of a vignette.

The dependent variables are respondents’ evaluations of the entrants’ trustworthiness and desire for long-term cooperation. After reading each profile, the respondents were asked which representative they considered more trustworthy and were required to select an entrant to cooperate with in the long term. We also recorded the respondents’ major demographic information, including age, gender, income level, type of work, and scale of the company they were working for. Following the common practice of DCE, we invited each respondent to complete three rounds of the experiment.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Descriptive statistics

Online Appendix D provides a demographic summary of the 272 respondents. Approximately 20% were female (227 men versus 45 women), which is close to the percentage of female entrepreneurs in China (25%) (All-China Women’s Federation, 2010). The treatment was balanced across the observed demographic characteristics. In addition, 76% of the respondents reported that they cannot tolerate more than 250 mL of high-alcohol liquor, which echoes our fieldwork finding that to drink 250 mL of liquor (a test by potential partners) would put a heavy burden on the entrants. Moreover, 39% of respondents reported that they can drink no more than 100 mL of liquor, an amount that could be easily reached in a heavy-drinking banquet, as estimated previously. 87% of the respondents were aware that a red face indicates low alcohol tolerance, which supports our use of red face and vomiting as proxies for low alcohol tolerance. Our respondents also generally agreed that heavy drinking harms one’s health: 93% of the respondents admitted that drinking has negative health outcomes, and 56% considered the effect to be strong, consistent with scientific findings (CDC, 2019; Lobo & Harris, 2008; Room et al., 2005).

4.2.2 Testing the main effect

We first test the main effect of heavy drinking on cooperation outcomes (Proposition 2), as it is worthwhile to further test the mechanism (Proposition 1) only if the effect holds. Results are presented in Table 1. Column 1 shows the coefficients of the logistic regressions testing whether heavy drinking promotes cooperation (i.e., whether guanxi is formed). The respondents showed a statistically significant preference for cooperating with heavy-drinking entrants rather than those making a token gesture, which is consistent with Proposition 2. The marginal effect of the variable Heavy Drink is as large as 0.104 and statistically significant at the 0.01 level, which means that a heavy drinker is 10.9% more likely to be selected than an entrant making a token gesture.

The coefficient of Red Face in column 1 suggests that those who send the signal of low alcohol tolerance have a higher probability (6% points) of achieving long-term business cooperation than other entrants. However, the effect is marginally significant at the 0.1 level. We did not propose a direct effect of red face on cooperation previously; however, its limited stand-alone effect on cooperation may align with our ethnographic observations, in which signal receivers use it as a clue to determine if someone claiming to have consumed their maximum alcohol capacity is actually drunk. In other words, it reinforces the credibility of the heavy-drinking signal instead of representing an independent signal of cooperativeness. Thus, the sizable marginal effect of Red Face (0.06) indicates potential treatment-effect heterogeneity, as conjectured in Proposition 3, which we test later.

The coefficient of Maotai shows that offering luxury liquor gives entrants a significant competitive advantage. Compared with offering a good ordinary liquor such as Jian Nan Chun, offering Maotai makes an entrant 6.6% more likely to be picked as a long-term business partner, which helps to explain why Maotai is so popular at Chinese business banquets. At the same time, considering that high-end wines such as Maotai are frequently given as a business gift in China, the relatively small effect of Maotai compared with that of heavy drinking reinforces the preeminent role of drinking, complemented by gift giving, in business cooperation.

As our treatment was balanced across different personal characteristics, the possible confounding effects from them were minimal. Nevertheless, we checked the robustness of our results by controlling for demographic variables, including gender, age, income level, whether the respondent worked in the private sector, and the number of employees at the respondent’s company. The thirty respondents who did not provide full demographic information were dropped from the data set. The results are robust, and the marginal effects of several key treatments actually increased (column 2 of Table 1).

4.2.3 Testing the mechanisms

We now test the underlying signaling mechanism: heavy drinking signals the trustworthiness of the host and therefore increases the likelihood of cooperation (Proposition 1). We start with the correlation between the drinking attributes and the proposed intermediate variable (trustworthiness). As presented in column 3 of Table 1, the coefficient of Heavy Drinking is highly significant, indicating that heavy drinking sends the signal of trustworthiness. We also control for other personal characteristics, and the positive effect of heavy drinking on trustworthiness persists (column 4). Finally, we examine the relationship between trust and long-term cooperation and find positive statistical significance (Appendix E). The two parts of the findings together prove that the cooperation outcome in Proposition 1 follows our proposed theory of heavy social drinking, according to which heavy drinking is interpreted by potential partners as a sign of trustworthiness, which they need to be convinced of in order to accept the entrant into their network.

Neither Red Face nor Maotai alone provides a similar effect to Heavy Drinking as shown by their coefficients in columns 3 and 4 of Table 1. The insignificance of Red Face might appear to contradict the previously mentioned interview comment that people tend to put more trust in individuals whose faces turn red after drinking. However, what the interviewee said could be conditional on the signal sender’s drinking efforts, which can only be clearly separated through a rigorous test of the heterogeneous treatment effect.

4.2.4 The heterogeneous effect of Red Face

To explore treatment-effect heterogeneity, we estimate the effect of red face on cooperation under the conditions of heavy and light drinking separately. To do this, we divide the data into two subsets based on the Agency A representative’s drinking effort, therefore forming two groups, heavy and light drinking. For each group, we employ the same model—namely, one with cooperation as the dependent variable and alcohol tolerance (i.e., red face vs. looks no different) as the key independent variable. We also include the same set of personal characteristics: age, gender, income level, type of work, and scale of company. The results are presented in Fig. 2.

As the bottom chart of Fig. 2 shows, the effect of Red Face is statistically significant in the heavy-drinking scenario, with 8.2% more likely to be selected for cooperation than those with high alcohol tolerance. By contrast, among the token-gesture group (those engaging in light drinking), entrants with red face see a much smaller effect of drinking on securing cooperation; the effect is not statistically significant in comparison with that for entrants whose faces do not change after drinking (the top chart in Fig. 2). This result indicates that the effect of low alcohol tolerance (red face) on business cooperation is mainly conditional on heavy drinking, as suggested by Proposition 3—that is, red face strengthens the positive effect of heavy drinking on cooperation. Red face after light drinking is not perceived as an effective signal by the receivers.

5 Discussion and conclusion

While interpersonal networks are often considered important for socioeconomic and business cooperation, especially in regimes with weak institutions, little is known about how outsiders can demonstrate their credibility and reliability to potential partners and join an existing network. Our research on drinking at banquets in China helps explain this. Drawing from ethnographic observations, interviews, and signaling theory, we developed propositions and found that drinking can help solve the information asymmetry problem that hampers the establishment of business networks. Through heavy drinking, entrants can signal their trustworthiness to potential partners, which helps them establish guanxi. This signaling effect is more salient if entrants exhibit low alcohol tolerance because heavy drinking usually entails higher health costs for them than for those with high alcohol tolerance, and their drunkenness is more evident. The DCE results largely evidence the signaling effects of drinking as predicted by our theory.

To enhance the guanxi established through heavy drinking at banquets, entrants who sincerely want to cooperate may resort to additional strategies such as gift giving to display their credibility and commitment. Our survey found considerable support for this point. 60% of the respondents admitted that additional gift giving after the banquet is necessary for securing cooperation, and half of the respondents acknowledged that gift giving is “very important.”

Our findings also indicate that drinking can affect social welfare as a side effect. By helping potential partners screen entrants by trustworthiness and to identify reliable cooperators, drinking functions as an informal institution promoting social exchange and cooperation that lacks formal enforcement. This accounts for why Chinese managers commonly use luxury food and alcohol to entertain clients and even bribe government officials (Cai et al., 2011; Zhu & Wu, 2014) and why luxurious banquets are one target of recent anticorruption initiatives in China (Shu & Cai, 2017; Zhu et al., 2017). The prevalence of drinking could also deter business investments. For instance, some interviewees from southern China who had low average alcohol intake mentioned their hesitation to invest in northern China out of fear of heavy-drinking norms. The social costs of expenditures on lavish banquets and participants’ sacrifice of health can be avoided or reduced if formal institutions become more effective in sustaining cooperation, enforcing exchange, and resolving conflicts.

Finally, while the sample size in our survey experiment was relatively small, that was because we focused on respondents with experience with Chinese business banquets. Future work could test our propositions on a larger sample. It could also compare the signaling effect of drinking across industries and regions to examine whether the signaling effect varies across industries and regions with different institutional conditions. Furthermore, it could investigate how the norm of drinking adapts to changes in socioeconomic constraints. As Leeson and Suarez (2015); Maltsev (2022b) remind us, private governance mechanisms are not static in nature, and a better understanding of their functioning requires dynamic consideration. In addition, more generally, future research may study other institutional mechanisms employed by out-group strangers to build trust and join existing networks and therefore enhance broader social cooperation.

Notes

Other examples of signaling include people harming themselves to display their dangerousness and thereby deter potential attacks or predation (Lin, 2022b; Gambetta, 2011), governments investing in risky R&D projects to signal their competence (Lamberova, 2021), and donations demonstrating generosity or income and thereby improving donors’ status (Bracha & Vesterlund, 2017).

Hereafter, the terms signal senders, entrants, and hosts are used interchangeably, as are signal receivers, network incumbents, potential partners, and guests.

Alcohol intake impairs cognition and motor skills, damages the liver, and kills brain cells; therefore, excessive consumption implies substantial health costs (Slingerland, 2021). As revealed by Griswold et al. (2018), alcohol use has been ranked as one of the most serious risk factors of human health worldwide.

The propositions can also be formulated based on the game equilibria.

Moutai Group’s market capitalization has reached a staggering US$329 billion, leading all other enterprises in China’s capital market.

Interview PP in Guangdong, 2021. We use the initials of the interviewees to code our interview transcripts.

Interview LD in Guangdong, 2021.

Interview PP in Guangdong, 2021, interview LL in Jiangxi, 2022, and interview ZG in Guangdong, 2023.

Interview TA in Jiangxi, 2024.

Interview NN in Guangdong, 2024.

Interview LD in Guangdong, 2021.

Interview LL in Jiangxi, 2022.

Interview PP in Guangdong, 2021, and interview MIU in Guangdong, 2023.

Interview LL in Jiangxi, 2022, and interview MIU in Guangdong, 2023.

“A 42-year-old man died after business drinking,” https://society.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnKdF4e, Global Network, October 15, 2018, accessed February 1, 2023.

Interview SN in Hebei, 2022, and interview YD in Guangdong, 2021.

Interview AF in Guangdong, 2023. Scholars and visitors from overseas also share similar experiences (Hessler, 2006; Sin & Yang, 2020). As suggested by Leeson (2008, 2014a), outsiders who follow heterogeneous social norms but seek to cooperate with local people often have to reduce their social distance by investing in costly signals such as obeying local norms—e.g., learning local people’s language (Landa, 2016).

Interview TA in Jiangxi 2024.

Interview PP in Guangdong, 2021.

Interview QZ in Guangdong, 2023. Interview LD in Guangdong, 2021, concurred.

Interview PP in Guangdong, 2021, interview QZ in Guangdong, 2023, and interview ZG in Guangdong, 2023.

References

Adler, M. (1991). From symbolic exchange to commodity consumption: Anthropological notes on drinking as a symbolic practice. In S. Barrows, & R. Room (Eds.), Drinking: Behavior and belief in modern history (pp. 376–398). University of California Press.

All-China Women’s Federation (2010). The achievements, challenges and promises of the elite women in Chinahttp://www.women.org.cn/art/2010/9/18/art_205_71701.html.

Aoki, M. (2001). Toward a comparative institutional analysis. MIT Press.

Au, P. H., & Zhang, J. (2016). Deal or no deal? The effect of alcohol drinking on bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 127, 70–86.

Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2021). Conjoint Survey experiments. In J. DruckmanD. Green (Ed.), Advances in experimental political science (pp. 19–41). Cambridge University Press.

Barrows, S., & Room, R. (1991). Introduction in drinking: Behavior and belief in modern history. In S. Barrows, & R. Room (Eds.), Drinking: Behavior and belief in modern history 1–25. University of California Press.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1652–1678.

Bereczkei, T., Birkas, B., & Kerekes, Z. (2010). Altruism towards strangers in need: Costly signaling in an industrial society. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(2), 95–103.

Bian, Y. (2001). Guanxi capital and social eating: Theoretical models and empirical analyses. In N. Lin, K. Cook, & R. Burt (Eds.), Social capital: Theory and research (pp. 275–295). Aldine de Gruyter.

Bian, Y. (2019). Guanxi, how China works. Wiley.

Bird, R. B., & Bird, D. W. (1997). Delayed reciprocity and tolerated theft: The behavioral ecology of food-sharing strategies. Current Anthropology, 38(1), 49–78.

Bird, R. B., & Smith, E. (2005). Signaling theory, strategic interaction, and symbolic capital. Current Anthropology, 46(2), 221–248.

Bird, R. B., Bird, D. W., Smith, E. A., & Kushnick, G. C. (2002). Risk and reciprocity in Meriam food sharing. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(4), 297–321.

Bracha, A., & Vesterlund, L. (2017). Mixed signals: Charity reporting when donations signal generosity and income. Games and Economic Behavior, 104, 24–42.

Brooks, P. J., Enoch, M. A., Goldman, D., Li, T. K., & Yokoyama, A. (2009). The alcohol flushing response: An unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Medicine, 6(3), e1000050.

Bulte, E., Wang, R., & Zhang, X. (2018). Forced gifts: The burden of being a friend. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 155, 79–98.

Burt, R. S., & Burzynska, K. (2017). Chinese entrepreneurs, social networks, and guanxi. Management and Organization Review, 13(2), 221–260.

Cai, H., Fang, H., & Xu, L. C. (2011). Eat, drink, firms, government: An investigation of corruption from the entertainment and travel costs of Chinese firms. The Journal of Law and Economics, 54(1), 55–78.

Camerer, C. (1988). Gifts as economic signals and social symbols. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 180–214.

Cao, C., Li, S. X., & Liu, T. X. (2020). A gift with thoughtfulness: A field experiment on work incentives. Games and Economic Behavior, 124, 17–42.

Carmichael, H. L., & MacLeod, W. B. (1997). Gift giving and the evolution of cooperation. International Economic Review, 485–509.

Carr, J. L., & Landa, J. T. (1983). The economics of symbols, clan names, and religion. The Journal of Legal Studies, 12(1), 135–156.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2019). Alcohol and cancer. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/alcohol/index.htm.

Chang, K. C. (2011). A path to understanding guanxi in China’s transitional economy: Variations on network behavior. Sociological Theory, 29(4), 315–339.

Cheng, Y., Mukhopadhyay, A., & Williams, P. (2020). Smiling signals intrinsic motivation. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(5), 915–935.

Chrzan, J. (2013). Alcohol: Social drinking in cultural context. Routledge.

Chwe, M. S. Y. (2013). Rational ritual: Culture, coordination, and common knowledge. Princeton University Press.

Clarke, D. C. (1996). Power and politics in the Chinese court system: The enforcement of civil judgments. Columbia Journal of Asian Law, 10, 1–91.

Clay, K. (1997). Trade without law: Private-order institutions in Mexican California. The Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 13(1), 202–231.

Cook, K. S., Hardin, R., & Levi, M. (2005). Cooperation without trust? Russell Sage Foundation.

Corazzini, L., Filippin, A., & Vanin, P. (2015). Economic behavior under the influence of alcohol: An experiment on time preferences, risk-taking, and altruism. PLoS One, 10(4), e0121530.

Diamond, P. A., & Hausman, J. A. (1994). Contingent valuation: Is some number better than no number? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(4), 45–64.

Fuller, R. C. (1995). Wine, symbolic boundary setting, and American religious communities. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 63(3), 497–517.

Gambetta, D. (2011). Codes of the underworld: How criminals communicate. Princeton University Press.

Gambetta, D., & Przepiorka, W. (2019). Sharing compromising information as a cooperative strategy. Sociological Science, 6, 352–379.

Gambetta, D., & Székely, Á. (2014). Signs and (counter) signals of trustworthiness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 106, 281–297.

Gintis, H., Smith, E. A., & Bowles, S. (2001). Costly signaling and cooperation. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 213(1), 103–119.

Glazer, A., & Konrad, K. A. (1996). A signaling explanation for charity. American Economic Review, 86(4), 1019–1028.

Gong, T. (2004). Dependent judiciary and unaccountable judges: Judicial corruption in contemporary China. China Review, 4(2), 33–54.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

Greif, A. (2006). Institutions and the path to the modern economy: Lessons from medieval trade. Cambridge University Press.

Griswold, M. G., Fullman, N., Hawley, C., Arian, N., Zimsen, S. R., Tymeson, H. D., & Farioli, A. (2018). Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 392(10152), 1015–1035.

Gurven, M., Allen-Arave, W., Hill, K., & Hurtado, M. (2000). It’s a wonderful life: Signaling generosity among the Ache of Paraguay. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21(4), 263–282.

Gusfield, J. (1987). Passage to play: Rituals of drinking time in American society. In M. Douglas (Ed.), Constructive drinking: Perspectives on drink from anthropology (pp. 73–90). Cambridge University Press.

Haber, S., Maurer, N., & Razo, A. (2003). The politics of property rights: Political instability, credible commitments, and economic growth in Mexico, 1876–1929. Cambridge University Press.

Hall, D. L., Cohen, A. B., Meyer, K. K., Varley, A. H., & Brewer, G. A. (2015). Costly signaling increases trust, even across religious affiliations. Psychological Science, 26(9), 1368–1376.

Haucap, J., & Herr, A. (2014). A note on social drinking: In Vino Veritas. European Journal of Law and Economics, 37, 381–392.

Heath, D. B. (2000). Drinking occasions: Comparative perspectives on alcohol and culture. Routledge.

Hessler, P. (2006). River town: Two years on the Yangtze. Harper Perennial.

Hurun Report (2019). China HNWI alcohol consumption report 2019.

Hwang, K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92(4), 944–974.

Kali, R. (1999). Endogenous business networks. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 15(3), 615–636.

Kiong, T. C., & Kee, Y. P. (1998). Guanxi bases, xinyong and Chinese business networks. British Journal of Sociology, 49(1), 75–96.

Lamberova, N. (2021). The puzzling politics of R&D: Signaling competence through risky projects. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(3), 801–818.

Landa, J. T. (1994). Trust, ethnicity, and identity: Beyond the new institutional economics of ethnic trading networks, contract law, and gift-exchange. University of Michigan Press.

Landa, J. T. (2016). Economic success of Chinese merchants in Southeast Asia: Identity, ethnic cooperation and conflict. Springer.

Lee, C. H., Lee, J. M., Wu, D. C., Goan, Y. G., Chou, S. H., Wu, I. C., & Wu, M. T. (2008). Carcinogenetic impact of ADH1B and ALDH2 genes on squamous cell carcinoma risk of the esophagus with regard to the consumption of alcohol, tobacco and betel quid. International Journal of Cancer, 122(6), 1347–1356.

Lee, H., Kim, S. S., You, K. S., Park, W., Yang, J. H., Kim, M., & Hayman, L. L. (2014). Asian flushing: Genetic and sociocultural factors of alcoholism among east asians. Gastroenterology Nursing, 37(5), 327–336.

Leeson, P. T. (2008). Social distance and self-enforcing exchange. The Journal of Legal Studies, 37(1), 161–188.

Leeson, P. T. (2012). Ordeals. The Journal of Law and Economics, 55(3), 691–714.

Leeson, P. T. (2013). Gypsy law. Public Choice, 155, 273–292.

Leeson, P. T. (2014a). Anarchy unbound: Why self-governance works better than you think. Cambridge University Press.

Leeson, P. T. (2014b). Human sacrifice. Review of Behavioral Economics, 1(1–2), 137–165.

Leeson, P. T. (2014c). Oracles Rationality and Society, 26(2), 141–169.

Leeson, P. T., & Russ, J. W. (2018). Witch trials. The Economic Journal, 128(613), 2066–2105.

Leeson, P. T., & Suarez, P. A. (2015). Superstition and self-governance. In C. J. Coyne, & V. H. Storr (Eds.), New thinking in Austrian political economy (pp. 47–66). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Leeson, P. T., & Suarez, P. A. (2017). Child brides. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 144, 40–61.

Li, L. (2011). Performing bribery in China: Guanxi-practice, corruption with a human face. Journal of Contemporary China, 20(68), 1–20.

Li, J. (2024). Negotiating legality. Cambridge University Press.

Lin, W. (2022a). The roles of alcohol, cigarette and tea in social cooperation in China. Working paper.

Lin, W. (2022b). Garnering sympathy: Moral appeals and land bargaining under autocracy. Journal of Institutional Economics, 18(5), 767–784.

Lin, W., Wang, P., & Yuan, M. (2023). Governing the knowledge commons: Hybrid relational–contractual governance in China’s mining industry. World Development, 172, 106376.

Lobo, I. A., & Harris, R. A. (2008). GABAA receptors and alcohol. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 90(1), 90–94.

Louviere, J. J., Flynn, T. N., & Carson, R. T. (2010). Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. Journal of Choice Modelling, 3(3), 57–72.

Maltsev, V. V. (2022a). Dynamic anarchy: The evolution and economics of the beguny sect in eighteenth-twentieth century Russia. Public Choice, 190(1), 111–126.

Maltsev, V. V. (2022b). Economic effects of voluntary religious castration on the informal provision of cooperation: The case of the Russian Skoptsy sect. European Economic Review, 145, 104109.

Mares, I., & Visconti, G. (2020). Voting for the lesser evil: Evidence from a conjoint experiment in Romania. Political Science Research and Methods, 8(2), 315–328.

Moeran, B. (2021). The business of ethnography: Strategic exchanges, people and organizations. Routledge.

Ohtsubo, Y., & Watanabe, E. (2009). Do sincere apologies need to be costly? Test of a costly signaling model of apology. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30(2), 114–123.

Peerenboom, R. (2002). China’s long march toward rule of law. Cambridge University Press.

Peters, B. L., & Stringham, E. (2006). No booze? You may lose: Why drinkers earn more money than nondrinkers. Journal of Labor Research, 27(3), 411–421.

Posner, E. A. (1998). Symbols, signals, and social norms in politics and the law. The Journal of Legal Studies, 27(S2), 765–797.

Posner, E. A. (2009). Law and social norms. Harvard University Press.

Pullon, S. (2008). Competence, respect and trust: Key features of successful interprofessional nurse-doctor relationships. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 22(2), 133–147.

Qi, X. (2013). Guanxi, social capital theory and beyond: Toward a globalized social science. The British Journal of Sociology, 64(2), 308–324.

Richman, B. D. (2017). Stateless commerce. Harvard University Press.

Room, R., Babor, T., & Rehm, J. (2005). Alcohol and public health. The Lancet, 365(9458), 519–530.

Rotter, J. B. (1967). A New Scale for the measurement of Interpersonal Trust. Journal of Personality, 35(4), 651–665.

Ruan, J., & Wang, P. (2023). Elite capture and corruption: The influence of elite collusion on village elections and rural land development in China. The China Quarterly, 253, 107–122.

Sayette, M. A., Creswell, K. G., Dimoff, J. D., Fairbairn, C. E., Cohn, J. F., Heckman, B. W., & Moreland, R. L. (2012). Alcohol and group formation: A multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding. Psychological Science, 23(8), 869–878.

Schweitzer, M. E., & Gomberg, L. E. (2001). The impact of alcohol on negotiator behavior: Experimental evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(10), 2095–2126.

Seabright, P. (2010). The company of strangers: A natural history of economic life-revised edition. Princeton University Press.

Sherratt, A. (2014). Alcohol and its alternatives: Symbol and substance in pre-industrial cultures. In J. Goodman, A. Sherratt, and P. E. Lovejoy Eds., Consuming Habits: Drugs in history and anthropology (second edition) 27–61. Routledge.

Shu, Y., & Cai, J. (2017). Alcohol bans: Can they reveal the effect of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign? European Journal of Political Economy, 50, 37–51.

Sina (2019). Sina report on the liquor industry in 2018. https://www.cbndata.com/report/1723/detail?isReading=report&page=1.

Skarbek, D., & Wang, P. (2015). Criminal rituals. Global Crime, 16(4), 288–305.

Slingerland, E. (2021). Drunk: How we sipped, danced, and stumbled our way to civilization. Little, Brown Spark.

Sohu (2013). Sohu report on the liquor industry in 2012.

Soler, M. (2012). Costly signaling, ritual and cooperation: Evidence from Candomblé, an afro-brazilian religion. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(4), 346–356.

Sosis, R., Kress, H. C., & Boster, J. S. (2007). Scars for war: Evaluating alternative signaling explanations for cross-cultural variance in ritual costs. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(4), 234–247.

Standifird, S. S., & Marshall, R. S. (2000). The transaction cost advantage of guanxi-based business practices. Journal of World Business, 35(1), 21–42.

Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Gift giving, bribery and corruption: Ethical management of business relationships in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 20(2), 121–132.

Sterelny, K., & Hiscock, P. (2014). Symbols, signals, and the archaeological record. Biological Theory, 9, 1–3.

Su, C., & Littlefield, J. E. (2001). Entering guanxi: A business ethical dilemma in mainland China? Journal of Business Ethics, 33, 199–210.

Tsai, L. L., Trinh, M., & Liu, S. (2022). What makes anticorruption punishment popular? Individual-level evidence from China. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 602–606.

Wang, Y. (2013). Court funding and judicial corruption in China. The China Journal, 69(1), 43–63.

Wang, P. (2014). Extra-legal protection in China: How guanxi distorts China’s legal system and facilitates the rise of unlawful protectors. British Journal of Criminology, 54(5), 809–830.

Werner, R., & Keren, G. (1993). Hostages as a commitment device: A game-theoretic model and an empirical test of some scenarios. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 21(1), 43–67.

Yan, Y. (1996). The flow of gifts: Reciprocity and social networks in a Chinese village. Stanford University Press.

Yang, M. M. H. (1994). Gifts, favors, and banquets: The art of social relationships in China. Cornell University Press.

Zhan, J. V. (2012). Filling the gap of formal institutions: The effects of Guanxi network on corruption in reform-era China. Crime law and Social Change, 58, 93–109.

Zhan, J. V. (2022). China’s contained resource curse: How minerals shape state capital labor relations. Cambridge University Press.

Zhu, J. (2012). The shadow of the skyscrapers: Real estate corruption in China. Journal of Contemporary China, 21(74), 243–260.

Zhu, J., & Wu, Y. (2014). Who pays more tributes to the government? Sectoral corruption of China’s private enterprises. Crime Law and Social Change, 61(3), 309–333.

Zhu, J., Zhang, Q., & Liu, Z. (2017). Eating, drinking, and power signaling in institutionalized authoritarianism: China’s antiwaste campaign since 2012. Journal of Contemporary China, 26(105), 337–352.

Acknowledgements

• The authors thank Shaoping Jiang, Peter Leeson, Pinghan Liang, Liang Ma, Duoduo Xu, the three anonymous reviewers, and all the participants of the International Public Administration Conference at Renmin University for providing useful comments. We also thank Yuxin Ding, Jiajian Chen, Yongjie Lin, and Ansheng Zhu for offering research assistance.

Funding

This research is supported by the HKGRF No.17605222 and HKU Seed Fund. The authors also acknowledge the support provided by the Post-doctoral Fellowship on Contemporary China, Faculty of Social Sciences, the University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This research involves human participants. Ethics approval has been received for this research. HREC reference number for this research is EA210349.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants were anonymously mentioned in the article as a protection.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest for this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, W., Kang, S., Zhu, J. et al. Till We Have Red Faces: Drinking to Signal Trustworthiness in Contemporary China. Public Choice (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-024-01180-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-024-01180-2