Abstract

Many theories have been proposed to explain why social expenditures have increased in industrialized countries. The determinants include globalization, political–institutional variables such as government ideology and electoral motives, demographic change, and economic variables, such as unemployment. Scholars have modeled social expenditures as the dependent variable in many empirical studies. We employ extreme bounds analysis and Bayesian model averaging to examine robust predictors of social expenditures. Our sample contains 31 OECD countries over the period between 1980 and 2016. The results suggest that trade globalization, the fractionalization of the party system, and fiscal balances are negatively associated with social expenditures. Unemployment, population aging, banking crises, social globalization, and public debt enter positively. Moreover, social expenditures have increased under left-wing governments when de facto trade globalization was prominent, and at the time of banking crises. We conclude that policymakers in individual countries rely on domestic conditions to craft social policies—globalization, aging, and business cycles notwithstanding.

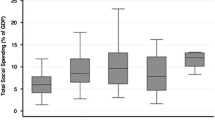

Source OECD

Source OECD

Source OECD

Source OECD

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Public social expenditure consists of cash and in-kind benefits for old age, survivors, disability, health, family, active labor market programs, unemployment, housing, and other social policies.

https://www.oecd.org/social/soc/OECD2019-Social-Expenditure-Update.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2019).

Duval et al. (2021) examine robust predictors of structural reforms.

Egger et al. (2019) find that during globalization, higher levels of public expenditures are financed by a smaller range of tax bases, such as middle class labor income.

Gözgör et al. (2019) show that increased economic globalization is associated with lower public employment.

Cameron (1978) hypothesized that countries that are more open are also more heavily unionized, which, increases social spending through collective bargaining. Rodrik (1998) showed that the correlation between openness and social spending is also found in developing countries with low levels of unionization. Social spending serves as a form of insurance against uncertainty and risks related to openness. Bergh (2021) proposes a revised compensation hypothesis.

Colantone et al. (2019) show, for example, how import competition induces mental distress in workers.

On the other hand, theories propose that public expenditures are not likely to be higher under minority than majority governments because minority governments are expected to be strong and stable when they consist of one large, centrally located party (Crombez 1996; Tsebelis 2002). The size of the government may be even smaller under minority governments because minority governments can choose among various potential partners, and select the least costly alternative.

Fiscal rules govern the way in which budgets are drafted by the government, amended and passed by the parliament, and then implemented by the government.

Of the 38 OECD countries, we exclude Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Israel, Korea, Mexico, and Turkey because data for some explanatory variables is not available for those countries. The data can be accessed here: https://www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm.

It includes public spending on early childhood education and care for children under the age of six, but excludes public spending on education beyond that age.

In Ireland, GDP (the denominator) increased by 25% in 2015, following the relocation of a small number of multinationals’ intellectual property assets to Ireland. In the Netherlands, the health care reform of 2006 relocated basic health insurance finance to private funds, which decreased public social spending.

The fractionalization of the party system is measured in the way that Rae (1968) proposed: \(fract=1-{\sum }_{i=1}^{m}{s}_{i}^{2}\), where s is the share of seats for party i, and m is the number of parties (the legislative fractionalization).

For simplicity, this term is used for the distribution on both sides of zero, that is for CDF(0) and 1-CDF(0). Sala-i-Martin (1997) proposes using the (integrated) likelihood to construct a weighted CDF(0). However, due to missing observations, the varying number of them in the regressions in some of the variables poses a problem. Sturm and de Haan (2001) show that this goodness-of-fit measure may not be a good indicator of the probability that a model is the true model, and the weights constructed in this way are not equivariant to linear transformations in the dependent variable. Hence, changing scales result in rather different outcomes and conclusions. Thus, we restrict our attention to the unweighted version.

References

Abrams, B. A., & Settle, R. F. (1999). Women’s suffrage and the growth of the welfare state. Public Choice, 100(3), 289–300.

Alesina, A. (1987). Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102, 651–678.

Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8, 155–194.

Alesina, A., & Drazen, A. (1991). Why are stabilizations delayed? A political economy model. American Economic Review, 81(5), 1170–1188.

Alesina, A., & Tabellini, G. (1990). A positive theory of fiscal deficits and government debt. Review of Economic Studies, 57, 403–414.

Alesina, A., & Wacziarg, R. (1998). Openness, country size and government. Journal of Public Economies, 69(3), 305–321.

Alt, J. E., & Lassen, D. (2006a). Transparency, political polarization and political budget cycles in OECD countries. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 530–550.

Alt, J. E., & Lassen, D. (2006b). Fiscal transparency, political parties and debt in OECD countries. European Economic Review, 50, 1403–1439.

Alt, J. E., & Rose, S. S. (2009). Context-conditional political budget cycles. In C. Boix & S. C. Stokes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics. Oxford University Press.

Armingeon, K., Isler, C., Knöpfel, L., Weisstanner, D., & Engler, S. (2018). Comparative political data set 1960–2016. Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. http://www.cpds-data.org/

Becker, G. S. (1957). The economics of discrimination. University of Chicago Press.

Benabou, R. (1996). Heterogeneity, stratification, and growth: Macroeconomic implications of community structure and school finance. American Economic Review, 86, 584–609.

Benabou, R. (2000). Unequal societies: Income distribution and the social contract. American Economic Review, 90, 96–129.

Bergh, A. (2021). The compensation hypothesis revisited and reversed. Scandinavian Political Studies, 44, 140–147.

Bergh, A., Mirkina, I., & Nilsson, T. (2020). Can social spending cushion the inequality effect of globalization? Economics and Politics, 32, 104–142.

Bjørnskov, C., & Rode, M. (2020). Regime types and regime change: A new dataset on democracy, coups, and political institutions. Review of International Organizations, 15, 531–551.

Bohn, F., & Sturm, J.-E. (2021). Do expected downturns kill political budget cycles? Review of International Organizations, 16, 817–841.

Borck, R. (2019). Political participation and the welfare state. In R. D. Congleton & B. Grofman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public choice (Vol. 2). Oxford University Press.

Borge, L. E., & Rattso, J. (2004). Income distribution and tax structure: Empirical test of the Meltzer-Richard hypothesis. European Economic Review, 48, 805–826.

Börsch-Supan, A. (1995). The impact of population aging on savings, investment and growth in the OECD area. Discussion Papers. Institut für Volkswirtschaftslehre und Statistik 512.

Bove, V., Efthyvoulou, G., & Navas, A. (2017). Political cycles in public expenditure: Butter vs guns. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45, 582–604.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2005). Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52, 1271–1295.

Breyer, F., & Craig, B. (1997). Voting on social security: Evidence from OECD countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 13(4), 705–724.

Breyer, F., & Stolte, K. (2001). Demographic change, endogenous labour supply and the political feasibility of pension reform. Journal of Population Economics, 14(3), 409–424.

Cameron, D. R. (1978). The expansion of the public economy: A comparative analysis. American Political Science Review, 72(4), 1243–1261.

Cascio, E. U., & Washington, E. (2014). Valuing the vote: The redistribution of voting rights and state funds following the voting rights act of 1965. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), 379–433.

Cederman, L. E., Wimmer, A., & Min, B. (2010). Why do ethnic groups rebel? New data and analysis. World Politics, 62(1), 87–119.

Chappell, H. W., & Keech, W. R. (1986). Party differences in macroeconomic policies and outcomes. American Economic Review, 76, 71–74.

Colantone, I., Crino, R., & Ogliari, L. (2019). Globalization and mental distress. Journal of International Economics, 119, 181–207.

Crombez, C. (1996). Minority governments, minimal winning coalitions and surplus majorities in parliamentary systems. European Journal of Political Research, 29, 1–29.

Cruz, C., Keefer, P., & Scartascini, C. (2018). Database of political institutions 2017. https://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/8806

Dahan, M., & Strawczynski, M. (2013). Fiscal rules and the composition of government expenditures in OECD countries. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32, 484–504.

de Haan, J., & Klomp, J. (2013). Conditional budget cycles: A review of recent evidence. Public Choice, 157, 387–410.

de Haan, J., & Sturm, J.-E. (1994). Political and institutional determinants of fiscal policy in the European community. Public Choice, 80, 157–172.

de Haan, J., & Sturm, J.-E. (1997). Political and economic determinants of OECD budget deficits and government expenditures: A reinvestigation. European Journal of Political Economy, 13, 739–750.

de Haan, J., Sturm, J.-E., & Beekhuis, G. (1999). The weak government thesis: Some new evidence. Public Choice, 101, 163–176.

de Van Velthoven, A., Haan, J., & Sturm, J.-E. (2019). Finance, income inequality and income redistribution. Applied Economics Letters, 26(14), 1202–1209.

Desmet, K., Ortuño-Ortín, I., & Wacziarg, R. (2012). The political economy of linguistic cleavages. Journal of Development Economics, 97(2), 322–338.

Desmet, K., Weber, S., & Ortuño-Ortín, I. (2009). Linguistic diversity and redistribution. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(6), 1291–1318.

Devereux, M. P., Griffith, R., & Klemm, A. (2002). Corporate income tax reforms and international tax competition. Economic Policy, 17(35), 449–495.

Devereux, M. P., Lockwood, B., & Redoano, M. (2008). Do countries compete over corporate tax rates? Journal of Public Economics, 92, 1210–1235.

Dreher, A. (2006). Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization. Applied Economics, 38(10), 1091–1110.

Dreher, A., Gaston, N., & Martens, P. (2008a). Measuring globalisation—Gauging its consequences. Springer.

Dreher, A., Sturm, J.-E., & Ursprung, H. W. (2008b). The impact of globalization on the composition of government expenditures: Evidence from panel data. Public Choice, 134, 263–292.

Dreher, A., Sturm, J.-E., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009a). Development aid and international politics: Does membership on the UN Security Council influence World Bank decisions?. Journal of Development Economics, 88, 1–18.

Dreher, A., Sturm, J.-E., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009b). Global horse trading: IMF loans for votes in the United Nations Security Council. European Economic Review, 53, 742–757.

Dubois, E. (2016). Political business cycles 40 years after Nordhaus. Public Choice, 166, 235–259.

Dutt, P., & Mitra, D. (2005). Political ideology and endogenous trade policy: An empirical investigation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(1), 59–72.

Dutt, P., & Mitra, D. (2006). Labor versus capital in trade-policy: The role of ideology and inequality. Journal of International Economics, 69(2), 310–320.

Duval, R., Furceri, D., & Miethe, J. (2021). Robust political economy correlates of major product and labor market reforms in advanced economies: Evidence from BAMLE for Logit Models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 36, 98–124.

Egger, P., Nigai, S., & Strecker, N. M. (2019). The taxing deed of globalization. American Economic Review, 109(2), 353–390.

Epifani, P., & Gancia, G. (2009). Openness, government size and the terms of trade. Review of Economic Studies, 76(2), 629–668.

Fujiwara, T. (2015). Voting technology, political responsiveness, and infant health: Evidence from Brazil. Econometrica, 83(2), 423–464.

Galasso, V., & Profeta, P. (2007). How does ageing affect the welfare state? European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 554–563.

Garrett, G. (1998). Partisan politics in the global economy. Cambridge University Press.

Garrett, G., & Mitchell, D. (2001). Globalization, government spending and taxation in the OECD. European Journal of Political Research, 39, 145–177.

Gaston, N., & Rajaguru, G. (2013a). International migration and the welfare state revisited. European Journal of Political Economy, 29, 90–101.

Gaston, N., & Rajaguru, G. (2013b). International migration and the welfare state: Asian perspectives. Journal of the Asia–Pacific Economy, 18, 271–289.

Godefroy, R., & Henry, E. (2016). Voter turnout and fiscal policy. European Economic Review, 89, 389–406.

Gonzales, M. D. L. A. (2002). Do changes in democracy affect the political budget cycle? Evidence from Mexico. Review of Developmental Economics, 6, 204–224.

Gözgör, G., Biglin, M. H., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2019). Public employment decline in developing countries in the 21st century: The role of globalization. Economics Letters, 184, 108608.

Grilli, V., Masciandaro, D., & Tabellini, G. (1991). Political and monetary institutions and public financial policies in the industrial countries. Economic Policy, 13, 341–392.

Gründler, K. (2019). Wealth inequality and public redistribution: First empirical evidence. Working Paper.

Gründler, K., & Köllner, S. (2017). Determinants of governmental redistribution: Income distribution, development levels, and the role of perceptions. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45(4), 930–962.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2016). Democracy and growth: Evidence from a machine learning indicator. European Journal of Political Economy, 45, 85–107.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2018). Machine learning indices, political institutions, and economic development. CESifo Working Paper No. 6930.

Gygli, S., Haelg, F., Potrafke, N., & Sturm, J.-E. (2019). The KOF Globalisation Index—Revisited. Review of International Organizations, 14(3), 543–574.

Hartwig, J., & Sturm, J.-E. (2014). Robust determinants of health care expenditure growth. Applied Economics, 46(36), 4455–4474.

Hartwig, J., & Sturm, J.-E. (2019). Do fiscal rules breed inequality? First evidence for the EU. Economics Bulletin, 39, 2.

Heinemann, F., Moessinger, M.-D., & Yeter, M. (2018). Do fiscal rules constrain fiscal policy? A meta-regression analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 51, 69–92.

Herwartz, H., & Theilen, B. (2014). Partisan influence on social spending under market integration, fiscal pressure and institutional change. European Journal of Political Economy, 34, 409–424.

Herwartz, H., & Theilen, B. (2017). Ideology and redistribution through public spending. European Journal of Political Economy, 46, 74–90.

Hibbs, D. A. (1977). Political parties and macroeconomic policy. American Political Science Review, 71, 1467–1487.

Hodler, R., Luechinger, S., & Stutzer, A. (2015). The effects of voting costs on the democratic process and public finances. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(1), 141–171.

Hoffman, M., León, G., & Lombardi, M. (2017). Compulsory voting, turnout, and government spending: Evidence from Austria. Journal of Public Economics, 145, 103–115.

Iversen, T. (2001). The dynamics of the welfare state expansion: Trade openness, de-industrialization, and partisan politics. In P. Pierson (Ed.), The new politics of the welfare state (pp. 45–79). Oxford University Press.

Kittel, B., & Obinger, H. (2003). Political parties, institutions and the dynamics of social expenditure in times of austerity. Journal of European Public Policy, 10, 20–45.

Kleven, H. J., Landais, C., Saez, E., & Schultz, E. (2014). Migration and wage effects of taxing top earners: Evidence from the foreigners’ tax scheme in Denmark. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), 333–378.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2018). Systematic banking crisis revisited. IMF Working Paper, 18/206.

Leamer, E. E. (1985). Sensitivity analyses would help. American Economic Review, 75, 308–313.

Leibrecht, M., Klien, M., & Onaran, O. (2011). Globalization, welfare regimes and social protection expenditures in Western and Eastern European countries. Public Choice, 148(3–4), 569–594.

Levine, R., & Renelt, D. (1992). A sensitivity analysis of cross country growth regressions. American Economic Review, 82, 942–963.

Lijphart, A. (1984). Measures of cabinet durability: A conceptual and empirical evaluation. Comparative Political Studies, 17, 265–279.

Lijphart, A. (1997). Unequal participation: Democracy’s unresolved dilemma. American Political Science Review, 91(1), 1–14.

Lim, S., & Burgoon, B. (2020). Globalization and support for unemployment spending in Asia: Do Asian citizens want to embed liberalism? Socio-economic Review, 18, 519–553.

Lledo, V., Yoon, S., Fang, X., Mbaye, S., & Kim Y. (2017). Fiscal rules at a glance. http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/FiscalRules/map/map.htm

Magnus, J., Powell, O., & Prüfer, P. (2010). A comparison of two model-averaging techniques with an application to growth empirics. Journal of Econometrics, 154, 139–153.

McManus, I. (2019). The re-emergence of partisan effects on social spending after the global financial crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57, 1274–1291.

Meinhard, S., & Potrafke, N. (2012). The globalization–welfare state nexus reconsidered. Review of International Economics, 20(2), 271–287.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927.

Mian, A., Sufi, A., & Trebbi, F. (2014). Resolving debt overhang: Political constraints in the aftermath of financial crisis. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 6(2), 1–28.

Milanovic, B. (2000). The median-voter hypothesis, income inequality, and income redistribution: An empirical test with the required data. European Journal of Political Economy, 16(3), 367–410.

Milesi-Ferretti, G.-M., Perotti, R., & Rostagno, M. (2002). Electoral systems and public spending. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2), 609–657.

Moser, C., & Sturm, J.-E. (2011). Explaining IMF lending decisions after the Cold War. Review of International Organizations, 6, 307–340.

Mueller, D. C., & Stratmann, T. (2003). The economic effects of democratic participation. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 2129–2155.

Nerlich, C., & Reuter, W. H. (2013). The design of national fiscal frameworks and their budgetary impact. ECB Working Paper Number 1588.

Nordhaus, W. D. (1975). The political business cycle. Review of Economic Studies, 42, 169–190.

Onaran, O., & Boesch, V. (2014). The effect of globalisation on the distribution of taxes and social expenditures in Europe: Do welfare state regimes matter? Environment and Planning A, 46, 373–397.

Onaran, O., Boesch, V., & Leibrecht, M. (2012). How does globalisation affect the implicit tax rates on labor income, capital income, and consumption in the European Union? Economic Inquiry, 50(4), 880–904.

Ostry, J., Berg, A., & Tsangarides, C. G. (2014). Redistribution, inequality and growth. IMF Staff Discussion Note.

Pecoraro, B. (2017). Why don’t voters ‘put the Gini back in the bottle’? Inequality and economic preferences for redistribution. European Economic Review, 93, 152–172.

Penner, R. C., & Weisner, M. (2001). Do state budget rules affect welfare spending? The Urban Institute Occasional Paper Number 43.

Persson, T., Gérard, R., & Tabellini, G. (1998). Towards micropolitical foundations of public finance. European Economic Review, 42, 685–694.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (1999). The size and scope of government: Comparative government with rational politicians. European Economic Review, 43, 699–735.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2002). Do electoral cycles differ across political systems? (Mimeo). IIES, Stockholm University.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effect of constitutions. MIT Press.

Pleninger, R., & Sturm, J.-E. (2020). The effects of economic globalization and ethnic fractionalization on redistribution. World Development, 130, 104945.

Potrafke, N. (2009). Did globalization restrict partisan politics? An empirical evaluation of social expenditures in a panel of OECD countries. Public Choice, 140, 105–124.

Potrafke, N. (2015). The evidence on globalisation. World Economy, 38(3), 509–552.

Potrafke, N. (2017). Partisan politics: The empirical evidence from OECD Panel studies. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45, 712–750.

Potrafke, N. (2018). Government ideology and economic policy-making in the United States—A survey. Public Choice, 174, 145–207.

Potrafke, N. (2019). The globalization–welfare state nexus: Evidence from Asia. World Economy, 43(3), 959–974.

Potrafke, N. (2021). Fiscal performance of minority governments: New empirical evidence for OECD countries. Party Politics, 27, 501–514.

Rae, D. W. (1968). A note on the fractionalization of some European party systems. Comparative Political Studies, 1, 413–418.

Razin, A., Sadka, E., & Swagel, P. (2002). The aging population and the size of the welfare state. Journal of Political Economy, 110(4), 900–918.

Rodrik, D. (1998). Why do more open economies have bigger governments? Journal of Political Economy, 106(5), 997–1032.

Rogoff, K. (1990). Equilibrium political budget cycles. American Economic Review, 80, 21–36.

Rogoff, K., & Sibert, A. (1988). Elections and macroeconomic policy cycles. Review of Economic Studies, 55, 1–16.

Rose, S. (2006). Do fiscal rules dampen the political business cycle? Public Choice, 128, 407–431.

Saalfeld, T. (2013). Economic performance, political institutions and cabinet durability in 28 European parliamentary democracies, 1945–2011. In W. C. Müller & H. M. Narud (Eds.), Party governance and party democracy (pp. 51–79). Springer.

Sala-i-Martin, X. (1997). I just ran two million regressions. American Economic Review, 87, 178–183.

Sala-i-Martin, X., Doppelhofer, G., & Miller, R. I. (2004). Determinants of long-term growth: A Bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach. American Economic Review, 94, 813–835.

Santos, M., & Simoes, M. (2021). Globalisation, welfare models and social expenditure in OECD countries. Open Economies Review, 32, 1063–1088.

Saunders, P., & Klau F. (1985). The role of the public sector: Causes and consequences of the growth of government. OECD Economic Studies (4).

Savage, L. (2019). The politics of social spending after the great recession: The re-turn of partisan policymaking. Governance, 32(1), 123–141.

Schmidt, M. G. (1996). When parties matter: A review of the possibilities and limits of partisan influence on public policy. European Journal of Political Research, 30(2), 155–183.

Schmitt, C. (2016). Panel data analysis and partisan variables: How periodization does influence partisan effects. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(10), 1442–1459.

Schuknecht, L., & Zemanek, H. (2021). Public expenditures and the risk of social dominance. Public Choice, 188, 95–120.

Schulze, G. G., & Ursprung, H. W. (1999). Globalisation of the economy and the nation state. World Economy, 22(3), 295–352.

Shelton, C. A. (2007). The size and composition of government. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 647–651.

Shelton, C. A. (2008). The aging population and the size of the welfare state: Is there a puzzle? Journal of Public Economics, 92(3–4), 647–651.

Shi, M., & Svensson, J. (2006). Political budget cycles: Do they differ across countries and why? Journal of Public Economics, 90, 1367–1389.

Sinn, H.-W. (1997). The selection principle and market failure in systems competition. Journal of Public Economics, 66(2), 247–274.

Sinn, H.-W. (2003). The new systems competition. Oxford.

Solt, F. (2009). Standardizing the World Income Inequality Database. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 231–242.

Starke, P. (2006). The politics of welfare state retrenchment: A literature review. Social Policy and Administration, 40(1), 104–120.

Streb, J. M., & Torrens, G. (2013). Making rules credible: Divided government and political budget cycles. Public Choice, 156, 703–722.

Sturm, J.-E., & de Haan, J. (2001). How robust is Sala-i-Martin’s robustness analysis (Mimeo). University of Groningen.

Sturm, J.-E., & de Haan, J. (2015). Income inequality, capitalism and ethno-linguistic fractionalization. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 105, 593–597.

Sturm, J.-E., & Williams, B. (2010). What determines differences in foreign bank efficiency? Australian evidence. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 20, 284–309.

Temple, J. (2000). Growth regressions and what the textbooks don’t tell you. Bulletin of Economic Research, 52, 181–205.

Tepe, M., & Vanhuysse, P. (2009). Are aging OECD welfare states on the path to gerontocracy? Evidence from 18 democracies, 1980–2002. Journal of Public Policy, 29(1), 1–28.

Tsebelis, G. (2002). Veto players. Princeton University Press.

Ursprung, H. W. (2008). Globalisation and the welfare state. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Visser, J. (2019, June). ICTWSS Database. Version 6.0. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies (AIAS), University of Amsterdam.

Vogt, M., Bormann, N. C., Rüegger, S., Cederman, L. E., Hunziker, P., & Girardin, L. (2015). Integrating data on ethnicity, geography, and conflict: The ethnic power relations data set family. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(7), 1327–1342.

Von Hagen, J. (1991). A note on the empirical effectiveness of formal fiscal restraints. Journal of Public Economics, 44, 99–110.

Von Hagen, J. (1992). Budgeting procedures and fiscal performance in the European Communities. Economic Papers, Commission of the European Communities, Nr. 96.

Warwick, P. V. (1979). The durability of coalition governments in parliamentary democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 11, 465–498.

Wenzelburger, G., & Zohlnhöfer, R. (2022). Bringing agency back into the study of partisan politics: A note on recent developments in the literature on party politics. Party Politics (forthcoming).

Yay, G. G., & Aksoy, P. (2018). Globalization and the welfare state. Quality and Quantity, 52(2), 1015–1040.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dirk Foremny, Regina Pleninger, Anna Raute, Cameron Shelton, the participants and discussants at the IIPF in Glasgow 2019, the virtual EEA 2020, the EPCS in Braga 2022, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Haelg, F., Potrafke, N. & Sturm, JE. The determinants of social expenditures in OECD countries. Public Choice 193, 233–261 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00984-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00984-4