Abstract

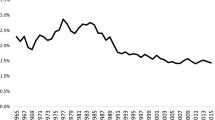

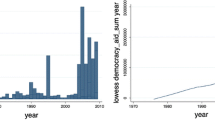

I investigate how the third wave of democracy influenced national defense spending by reference to a panel of 110 countries over the 1972–2013 period. I apply new data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute on military expenditures, which has been extended to years prior to 1988, and four democracy measures to address differences among indices of democracy. The results from a dynamic panel data model suggest that democracy’s third wave reduced defense spending relative to GDP by about 10% within countries that experienced democratization. I exploit the regional diffusion of democracy in the context of the third wave of democratization as an instrumental variable (IV) for democracy in order to overcome endogeneity problems. The IV estimates indicate that democracy reduced national defense spending relative to GDP by about 20% within countries that experienced democratization, demonstrating that OLS underestimates the effect of democracy on national defense spending. The cumulative long-run effect of democratization resulting from the dynamics in defense spending is almost three times larger for both OLS and IV estimates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Huntington (1991a, b, pp. 13–26) identifies three waves of democratization: the introduction of male suffrage in the United States and in European countries describes the first wave lasting from the 1820s until 1926. The second wave accounts for democratizations after the Second World War until the 1960 s in the former fascist European countries, countries like Japan, Korea and Turkey as well as in some Latin American countries that, however, quickly relapsed into autocratic regimes. The third wave started with the democratization of Portugal in 1974.

See also Wintrobe (1998) on the economics of autocratic regimes.

See Blum (2018) for a detailed discussion of the cited studies.

For some countries, for instance, SIPRI figures exclude military pensions, spending for paramilitary forces and spending for nuclear activities, or include spending for the police.

See https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex/sources-and-methods and https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex/frequently-asked-questions, both accessed November 9, 2019.

Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Nigeria, Nepal, Jordan, and Ghana are main troop contributors to UN peacekeeping missions as of 2013. UN peacekeeping missions represent important sources of income for those countries, which increased their defense spending as described by the SIPRI data. Since no information on troop contributions by country is available for the 1972–2013 period to explain peacekeeping-induced variations in defense spending, the countries are excluded. Furthermore, India and Pakistan became nuclear powers at some unknown point in time during the observation period, which might have caused them to reduce considerably their defense spending on conventional armaments relative to GDP.

The differences among the four democracy measures are tangible: a comparison between the dichotomous democracy measure of Bjørnskov and Rode (2019) and the dichotomous democracy measure of Gründler and Krieger (2016, 2018) shows considerable deviations, especially for African and Asian-Pacific countries. Contingent on a threshold Polity IV score above which a country is identified as a democracy, about 10% of the information from the Polity IV measure disagrees with the dichotomous democracy measure of Bjørnskov and Rode (2019). See Potrafke (2012, 2013) on how using Cheibub et al.’s (2010) measure changes established results and Gründler and Krieger (2016) on how machine learning based democracy measures resolve ambiguity about the relationship between democracy and economic growth.

Following the findings of Vreeland (2008) that sub-indices of the Polity IV index are closely correlated with civil war, the Polity IV index might confound the effect of democracy on defense spending with the effect of civil war on defense spending.

Acemoglu et al. (2019) employ a similar dynamic panel data model to estimate the effect of democracy on economic growth.

I apply the variable “Polity2” from the Polity IV dataset, which prorates the Polity IV index for the duration of interregnum periods.

Data for GDP are not available for the full observation period for Hungary, Poland and Romania. SIPRI data for military expenditure in levels and in shares of GDP therefore have been used to construct GDP figures for those countries. The procedure adopted is intended to capture variation in GDP over time for those countries accurately. GDP data from the World Bank, however, should not be compared with GDP data compiled from SIPRI figures; the comparability issue is, however, mitigated because the fixed effects model exploits the within-variation of countries only.

Note that the percentage impact of democracy, i.e., when the democracy dummy switches to one, is calculated as 100[e−0.196 – 1] = –17.8.

Note that the cumulative long-run effect of democracy is calculated as \(\hat{\mu }*\left( {1 - \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 2}^{5} \hat{\beta }_{j} } \right)^{ - 1} .\) with \(\hat{\mu }\) being the parameter estimate for the democracy measure, \(\hat{\beta }_{j}\) being the parameter estimate for the jth lag of the dependent variable and \((1 - \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 2}^{5} \hat{\beta}_{j})^{- 1}\) being the long-run multiplier for parameter estimates in a dynamic panel data model (Acemoglu et al. 2019). The long-run multiplier according to column (1) thus is calculated as [1 – (0.672 – 0.011 – 0.029 + 0.027)] – 1 = 2.9.

A Hausman test for a fixed-effects versus a random-effects model confirms that fixed-effects is the proper model of choice.

Note that military dictatorships and communist regimes are not mutually exclusive. Countries like Albania, Poland, and Laos were military and communist regimes at the same time according to Bjørnskov and Rode (2019).

The findings go back to the security web concept of Rosh (1988).

The SAR model also has been applied in most previous studies in this field (Goldsmith 2007; Skogstad 2016; George and Sandler 2018). Unlike the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM), the SAR model assumes that the spatial lags of the explanatory variables do not turn out to be jointly significant. Previous research corroborates that assumption because spatial lags of the determinants of defense spending have been shown to be hardly significant (Blum 2018). See LeSage and Pace (2009, pp. 32–33 and 155–158) for an overview of different spatial lag models.

LeSage and Pace (LeSage and Pace 2009, chapter 3) discuss maximum likelihood estimation in spatial lag models. Clustered standard errors turn maximum likelihood into a pseudo maximum likelihood because the computation of clustered standard errors follows a corrected assumption about the sample distribution (Cameron and Trivedi 2009, pp. 316–317). Likelihood-ratio tests for comparing specifications therefore are unfeasible.

Additional lags of the jackknifed democracy instruments did not turn out to be statistically significant in the first-stage regression.

References

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2013). Democratization and the size of government: Evidence from the long 19th century. Public Choice, 157(3/4), 511–542.

Albalate, D., Bel, G., & Elias, F. (2012). Institutional determinants of military spending. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40(2), 279–290.

Alptekin, A., & Levine, P. (2012). Military expenditure and economic growth: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 28, 636–650.

Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. A., Limongi, F., & Przeworski, A. (1996). Classifying political regimes. Studies in Comparative International Development, 31(2), 3–36.

Bjørnskov, C. (2019). Why do military dictatorships become presidential democracies? Mapping the democratic interests of autocratic regimes. Public Choice (forthcoming).

Bjørnskov, C., & Rode, M. (2019). Regime types and regime change: A new dataset on democracy, coups, and political institutions. The Review of International Organizations (forthcoming).

Blum, J. (2018). Defense burden and the effect of democracy: Evidence from a spatial panel analysis. Defence and Peace Economics, 29(6), 614–641.

Blum, J. (2019). Arms production, national defense spending and arms trade: Examining supply and demand. European Journal of Political Economy, 60, 101814.

Blum, J., & Potrafke, N. (2019). Does a change of government influence compliance with international agreements? Empirical evidence for the NATO two percent target. Defence and Peace Economics (forthcoming).

Bove, V., & Brauner, J. (2016). The demand for military expenditure in authoritarian regimes. Defence and Peace Economics, 27(5), 609–625.

Brauner, J. (2015). Military spending and democracy. Defence and Peace Economics, 26(4), 409–423.

Brückner, M., & Ciccone, A. (2011). Rain and the democratic window of opportunity. Econometrica, 79(3), 923–947.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2009). Microeconometrics using stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Caruso, R., & Francesco, A. (2012). Country survey: Military expenditure and its impact on productivity in Italy, 1988-2008. Defence and Peace Economics, 23(5), 471–484.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143, 67–101.

Collier, P., & Hoeffler, A. (2007). Unintended consequences: Does aid promote arms races? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(1), 1–27.

Doyle, M. W. (1983a). Kant, liberal legacies, and foreign affairs. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 12(3), 205–235.

Doyle, M. W. (1983b). Kant, liberal legacies, and foreign affairs, Part 2. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 12(4), 323–353.

Dreher, A. (2006). Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization. Applied Economics, 38, 1091–1110.

Dudley, L., & Montmarquette, C. (1981). The demand for military expenditures: An international comparison. Public Choice, 37, 5–31.

Dunne, P., & Perlo-Freeman, S. (2003a). The demand for military spending in developing countries. International Review of Applied Economics, 17(1), 23–48.

Dunne, P., & Perlo-Freeman, S. (2003b). The demand for military spending in developing countries: A dynamic panel analysis. Defence and Peace Economics, 14(4), 461–474.

Dunne, P., Perlo-Freeman, S., & Smith, R. P. (2008). The demand for military spending in developing countries: Hostility versus capability. Defence and Peace Economics, 19(4), 293–302.

Dunne, P., Perlo-Freeman, S., & Smith, R. P. (2009). Determining military expenditures: Arms races and spill-over effects in cross-section and panel data. UWE discussion paper, Bristol.

Dunne, P., Perlo-Freeman, S., & Soydan, A. (2004). Military expenditure and debt in small industrialized economies: A panel analysis. Defence and Peace Economics, 15(2), 125–132.

Dunne, P., Smith, R. P., & Willenbockel, D. (2005). Models of military expenditure and growth: A critical review. Defence and Peace Economics, 16(6), 449–461.

Eberhardt, M. (2019). Democracy does cause growth: Comment. CEPR discussion paper no. DP13659.

Fordham, B. O., & Walker, T. C. (2005). Kantian liberalism, regime type, and military resource allocation: Do democracies spend less? International Studies Quarterly, 49(1), 141–157.

Gates, S., Knutsen, T. L., & Moses, J. W. (1996). Democracy and peace: A more skeptical view. Journal of Peace Research, 33(1), 1–10.

Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2018). How dictatorships work. Power, personalization, and collapse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

George, J., & Sandler, T. (2018). Demand for military spending in NATO, 1968–2015: A spatial panel approach. European Journal of Political Economy, 53, 222–236.

Gleditsch, N. P., Wallensteen, P., Eriksson, M., Sollenberg, M., & Strand, H. (2002). Armed conflict 1946–2001: A new dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 39(5), 615–637.

Goldsmith, B. E. (2007). Arms racing in ‘space’: Spatial modelling of military spending around the world. Australian Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 419–440.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2016). Democracy and growth: Evidence from a machine learning indicator. European Journal of Political Economy, 45, 85–107.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2018). Machine learning indices, political institutions, and economic development. CESifo working paper no. 6930.

Gründler, K., & Krieger, T. (2019). Should we care (more) about data aggregation? Evidence from the democracy-growth-nexus. CESifo working paper no. 7480.

Gygli, S., Haelg, F., Potrafke, N., & Sturm, J.-E. (2019). The KOF globalization index—Revisited. Review of International Organizations, 14(3), 543–574.

Hamilton, J. D. (2018). Why you should never use the Hodrick-Prescott filter. Review of Economics and Statistics, 100(5), 831–843.

Hausken, K., Martin, C. W., & Plümper, T. (2004). Government spending and taxation in democracies and autocracies. Constitutional Political Economy, 15(3), 239–259.

Hegre, H. (2014). Democracy and armed conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 51(2), 159–172.

Huber, P. J. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (pp. 221–233).

Huntington, S. P. (1991a). Democracy’s third wave. Journal of Democracy, 2(2), 12–34.

Huntington, S. P. (1991b). The third wave: Democratization in the late 20th century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Jaggers, K., & Gurr, T. R. (1995). Tracking democracy’s third wave with the Polity III data. Journal of Peace Research, 32(4), 469–482.

Kammas, P., & Sarantides, V. (2019). Do dictatorships redistribute more? Journal of Comparative Economics, 47, 176–195.

Kant, I. (1795). Perpetual peace. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Kimenyi, M. S., & Mbaku, J. M. (1995). Rents, military elites, and the political democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 11, 699–708.

Knutsen, C. H., & Wig, T. (2015). Government turnover and the effects of regime type: How requiring alternation in power biases against the estimated economic benefits of democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 48(7), 882–914.

LeSage, J., & Pace, R. K. (2009). Introduction to spatial econometrics. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall.

Maoz, Z., & Russett, B. (1993). Normative and structural causes of democratic peace, 1946–1986. The American Political Science Review, 87(3), 624–638.

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2018). Polity IV project. Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2017. Dataset users’ manual. Center for Systemic Peace.

Munck, G. L., & Verkuilen, J. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: Evaluating alternative indices. Comparative Political Studies, 35(1), 5–34.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426.

Papaioannou, E., & Siourounis, G. (2008). Democratization and growth. The Economic Journal, 118, 1520–1551.

Plümper, T., & Martin, C. W. (2003). Democracy, government spending, and economic growth: A political-economic explanation of the Barro-Effect. Public Choice, 117(1/2), 27–50.

Potrafke, N. (2012). Islam and democracy. Public Choice, 151, 185–192.

Potrafke, N. (2013). Democracy and countries with Muslim majorities: A reply and update. Public Choice, 154, 323–332.

Rosh, R. M. (1988). Third world militarization: Security webs and the states they ensnare. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 32(4), 671–698.

Rota, M. (2011). Military burden and the democracy puzzle. MPRA paper no. 35254.

Russett, B. M., & O’Neal, J. R. (2001). Triangular peace: Democracy, interdependence, and international organizations. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Skogstad, K. (2016). Defence budgets in the post-Cold War era: A spatial econometrics approach. Defence and Peace Economics, 27(3), 323–352.

Stock, J., & Yogo, M. (2005). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In D. Andrews & J. Stock (Eds.), Identification and inference for econometric models: Essays in honour of Thomas Rothenberg (pp. 80–108). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Töngür, Ü., Hsu, S., & Elveren, A. Y. (2015). Military expenditures and political regimes: Evidence from global data, 1963–2000. Economic Modelling, 44(C), 68–79.

Vreeland, J. R. (2008). The effect of political regime on civil war. Unpacking anocracy. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(3), 401–425.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroscedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–838.

Wintrobe, R. (1990). The tinpot and the totalitarian: An economic theory of dictatorship. American Political Science Review, 84(3), 849–872.

Wintrobe, R. (1998). The political economy of dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yesilyurt, M. E., & Elhorst, J. P. (2017). Impacts of neighboring countries on military expenditures: A dynamic spatial panel approach. Journal of Peace Research, 54(6), 777–790.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Christian Bjørnskov, Klaus Gründler, Niklas Potrafke, the participants of the annual meeting of the European Public Choice Society (EPCS) 2019, the participants of the 3rd International Conference on the Political Economy of Democracy and Dictatorship (PEDD) 2019, and two anonymous referees for valuable comments. I thank Philippa Carr and Claire Jokubauskas for proofreading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Democracies 1972 and 2013 according to the dichotomous democracy measure of Bjørnskov and Rode (2019). The 1972 map is a contemporaneous political map and does not reflect countries and borders as of 1972. The entire territory of Germany, for example, is therefore labeled as a democracy in 1972

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blum, J. Democracy’s third wave and national defense spending. Public Choice 189, 183–212 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00870-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00870-x