Abstract

This paper seeks to examine the implications of policy intervention around elections on income inequality and fiscal redistribution. We first develop a simplified theoretical framework that allows us to examine election-cycle fiscal redistribution programs in the presence of a revolutionary threat from some groups of agents, i.e., when democracy is not “the only game in town”. According to our theoretical analysis, when democracy is not “the only game in town”, incumbents implement redistributive policies not only as a means of improving their reelection prospects, but also in order to signal that “democracy works”, thereby preventing a reversion to an autocratic status quo ante at a time of the current regime’s extreme vulnerability. Subsequently, focusing on 65 developed and developing countries over the 1975–2010 period, we report robust empirical evidence of pre-electoral budgetary manipulation in new democracies. Consistent with our theory, this finding is driven by political instability that induces incumbents to redistribute income—through tax and spending policies—in a relatively broader coalition of voters with the aim of consolidating the vulnerable newly established democratic regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Numerous studies of political budget cycles (PBCs) suggest that close to the Election Day, incumbents manipulate fiscal policy instruments in order to raise their reelection chances.Footnote 1 A strand of this literature places the spotlight on factors conditioning the occurrence and the strength of fiscal policy manipulation for electoral purposes (for a review of the literature on conditional PBCs, see Klomp and de Haan 2013a). Starting from Schuknecht (1996), the relevant literature suggests that fiscal manipulation is more likely in developing countries, because institutional checks and balances are weaker, allowing for greater political discretion over policy instruments.Footnote 2 Shi and Svensson (2006) provide evidence of electoral budget cycles in both developing and developed countries. However, they show that the effect is far stronger in the former, where information asymmetries between voters and politicians are more pronounced. Persson and Tabellini (2003, ch. 8) argue that electoral cycles exist in developed economies as well. They find a strong budgetary revenue cycle (government revenues as a percentage of GDP decline before elections) in developed countries, though no evidence of electoral cycle in the overall budget balance. Brender and Drazen (2005), on the other hand, argue that it is the age of the democratic regime, and not a nation’s level of economic development, that matters for the observed differences in electoral budget cycles. More precisely, they suggest that pre-electoral fiscal manipulation is stronger in new democracies because of the voters’ lack of familiarity with the electoral process.Footnote 3 Following this rationale, Hanusch and Keefer (2014) suggest that older political parties are able to address issues of credible commitment in a more effective way, and therefore, fiscal manipulation for electoral purposes is more likely to occur in the presence of younger political parties.

Another strand of the literature investigates how pre-electoral manipulation affects the composition rather than the level of public spending and tax receipts. More precisely, Schuknecht (2000) reports significant pre-electoral increases in public spending on infrastructure for a sample of 24 developing countries. Several studies based on regional data within countries have provided similar evidence (see, e.g., Khemani 2004; Drazen and Eslava 2010). These findings are consistent with the theoretical model of Drazen and Eslava (2010), according to which investment projects can be easily targeted to particular geographical constituencies, increasing very effectively the political support received by the incumbent. In contrast, Block (2002) and Vergne (2009) provide evidence that politicians in developing countries shift the composition of spending towards current expenditure and away from capital expenditure. Similar findings are obtained by Katsimi and Sarantides (2012) for a sample of OECD countries. The implication of that study is that policymakers seem to provide immediate benefit to voters by cutting current taxes, whereas capital spending falls. The theoretical justification for these findings dates back to Rogoff (1990). According to his argument, electorally motivated incumbents signal their competence by shifting public policy towards visible budget items and away from capital expenditures whose benefits can be discerned only in future periods.Footnote 4

This paper contributes to the relevant literature in two ways. First, it seeks to investigate the implications of pre-electoral manipulation of fiscal policy for income inequality. As already mentioned, previous empirical studies have verified the presence of electoral cycles in the size and the composition of public spending, as well as in the size and the composition of tax revenues (see, e.g., Persson and Tabellini 2003; Brender and Drazen, 2005; Katsimi and Sarantides 2012). These fiscal policy changes are expected to have electorally consequential distributional implications, which, to the best of our knowledge, have not been examined in prior studies. To this end, we employ data from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) in order to investigate the effect of electoral cycles on (1) market income inequality (i.e., Gini coefficients before taxes and transfers); (2) net income inequality (i.e., Gini coefficients after taxes and transfers); and (3) actual fiscal redistribution (i.e., the percentage changes in Gini indices before and after transfers and taxes).

Second, we extend the theoretical model of Aidt and Mooney (2014) in order to explore the distributional implications of an election that takes place “in the shadow of revolution”. The underlying feature of our model is that when the democratic regime is not fully consolidated (i.e., in a new democracy), the incumbent faces a potential threat of revolution from specific groups of agents, especially during pre-electoral periods (see, e.g., Fearon 2011; Little 2012; Little et al. 2015).Footnote 5 As such, incumbent politicians in new democracies collectively choose a pre-electoral fiscal policy taking into account the probability of a democratic regime’s collapse in addition to their own reelection probability.Footnote 6 In contrast, in established democracies the incumbent cares only about the strategy that will maximize the chances of remaining in office. This fundamental difference in the priorities of incumbents in new and established democracies leads to a significant divergence in their optimal pre-election strategies. More precisely, in stable democracies the incumbent allocates resources to middle-income agents, in which the “pivotal” group of voters is located, with no effect on actual fiscal redistribution. On the other hand, in new democracies incumbents also care about the regime’s stability; they therefore target the benefits of fiscal policy to a broader group of agents (which also includes low-income agents). The Gini coefficient, therefore, is affected as income is transferred away from the “rich”. Our theoretical results are in line with the empirical findings reported by Brender and Drazen (2005). However, in our model differences between new and old democracies are driven by the potential threat of revolution and not by the electorate’s lack of familiarity with the democratic process. Our intuition is closer to Brender and Drazen (2007), who suggested that the attitude of the citizenry towards democracy is important in preventing democratic collapse, and fiscal manipulation can act as an instrument to convince them that “democracy works”.

Our paper could also be related to a parallel literature that highlights the threat of revolution as a key ingredient in democratic transitions (see, e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson 2000, 2006; Przeworski 2009; Aidt and Jensen 2014). Starting from Tullock (1974), a large number of studies highlight that in many historical cases elites offered voting rights to poorer segments of the society in order to avoid revolutions. This is because extension of the voting franchise acts as a commitment mechanism for future fiscal redistribution from the elites (i.e., the rich) to the poor. This commitment can mitigate the threat of a “crude redistribution” that would result from a successful revolution fomented by the low-income agents.

All of these studies recognize the importance of the so-called de facto political power and consequently of the threat of revolution as a catalyst for democratic transitions.Footnote 7 However, they assume that de facto political power disappears just after the transition to a democratic regime and, therefore, it does not affect the implemented economic policy in democracies. Building on this rationale, the present paper suggests that de facto political power and the consequent threat of revolution can affect implemented economic policies even in democracies, especially during the first years of the transition. This is because in new democracies that are not fully consolidated, citizens face an option to revolt against the incumbent government if the latter fails to demonstrate a minimum level of competence. To this end, incumbents may opt for implementing pro-poor economic policies in order to convince the low-income agents that “democracy works”, mitigating the risk of revolution that can lead to a democratic regime’s collapse.Footnote 8

To test the theoretical predictions of the model, we focus our attention on a dataset of 65 developed and developing countries over the 1975–2010 period. Our analysis indicates that in new democracies elections exert a positive and significant impact on actual fiscal redistribution. Subsequently, we attempt to further corroborate our theoretical prediction that political instability is the driving force of our results. We measure instability using cross-country data on state repression and state violence. Our findings suggest that the effect of elections is stronger when new democracies are characterized by more political instability, especially when the latter is proxied by state violence. Consistent with the model, in vulnerable democratic regimes incumbent politicians allocate resources—through tax and spending polices—towards the poorer segments of society in order to convince them that “democracy works”, mitigating the risk of a potential revolution.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical analysis and deduces key implications. Section 3 describes the data and the empirical setup, whereas Sect. 4 presents the empirical results. Finally, Sect. 5 summarizes the main findings.

2 Theoretical framework

This section develops a simple theoretical model that borrows its main features from Lohmann (1998) and Aidt and Mooney (2014). Our theoretical framework allows us to compare the distributional implications of pre-electoral fiscal policies between new and established democracies.

We consider an economy populated by three types of individuals: rich (R) of size δ R, middle-income (M) of size δ M , and poor (P) of size δ P , in which we assume that δ M > δ R + δ P and δ R + δ M + δ P = 1. The rich, the middle-income group, and the poor have fixed incomes y R , y M , and y P , respectively, during periods t = 1, 2, where in addition we assume that y R > y M > y P . The tax rate (τ) is proportional to the income of each group, and it is fixed at a level of \(\tau = \bar{\tau }\) in both periods. The elected national government in each period collects tax revenues and runs a balanced budget. Moreover, it decides whether to use the given tax revenues in order to finance a lump-sum targeted transfer to the low-income group (\(T_{t}^{P}\)), or, alternatively to the middle-income group (\(T_{t}^{M}\)), or, finally, to the rich agents (\(T_{t}^{R}\)). The government decides also whether to extract resources from public funds by diverting tax revenues to private rents (\(r_{t}\)) for itself. Therefore, the government’s budget constraint is \(\delta_{P} T_{t}^{P} + \delta_{M} T_{t}^{M} + \delta_{R} T_{t}^{R} + r_{t} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\), where \(\bar{y}\) is the average income. An election takes place between the two periods.

Citizens’ well-being depends on three factors: (1) the budget allocation, (2) the quality of the politician running the government, and (3) random events (bad or good luck). The utility generated by the budget allocation and private consumption is as follows:

The quality of governance matters to the citizens because the utility they get from a given budget allocation increases with the quality of the incumbent politician. The total utility of each type of agent is, respectively, as follows:

where \(q_{t}\) is a quality shock, which determines how competent the incumbent is, and \(\mu_{t}\) is a “luck” shock that makes the incumbent look more or less competent than may be the case. The fundamental information assumption of the model is that the voters observe total utility, but they are unable to decompose this between lump sum transfers, the quality shock (\(q_{t}\)) and the “luck” shock (\(\mu_{t}\)).Footnote 9 Although the two shocks are unobserved, they are both drawn from known distributions. The luck shock (\(\mu_{t}\)) is drawn independently in each period and is equal to ±1/2, each occurring with probability \(p = 1/2\).Footnote 10 The quality shock (\(q_{t}\)) is a characteristic of the politician and follows a uniform distribution over \(\left[ { - \frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2}} \right]\). If the politician is reelected, the quality shock from period 1 also applies to period 2, whereas if a new politician is elected in period 2 a new quality shock is drawn from the above-mentioned known uniform distribution.

The total utility of the incumbent is increasing and quasi-concave. For algebraic simplicity, we use an additively separable function of the form:

where \(0 < \beta < 1\) is a discount factor and \(p_{I}\) is the probability that the incumbent is reelected. The quantity \(r_{t}\) denotes rents grabbed in period t = 1, 2, and E denotes the exogenous rents from winning the election.Footnote 11

We solve the model under two alternative political regimes. The first one (that will serve as benchmark) is an established democratic regime in which democracy is “the only game in town”. The second political regime is a newly established democracy wherein the incumbent faces a potential threat of revolution from some groups of agents.

2.1 Fiscal redistribution when democracy is “the only game in town”

First, consider the benchmark case of an established democracy. The timing of the events in this case is as follows: (1) At the beginning of period 1, a balanced budget \(\left\{ {T_{1}^{P} ,T_{1}^{M} ,T_{1}^{R} ,r_{1} } \right\}\) is implemented, and (2) the two random shocks \(q_{1}\) and \(\mu_{1}\) are realized. Random shocks are not observed directly by anyone, but all agents are able to observe total utility. (3) At the end of the first period, elections take place, and the voters either reelect the incumbent politician or elect a new politician. (4) The winner implements a balanced budget \(\left\{ {T_{1}^{P} ,T_{1}^{M} ,T_{1}^{R} ,r_{1} } \right\}\) in period 2. (5) A new luck shock \(\mu_{2}\) is realized. If the incumbent of the first period is reelected the quality shock from period 1 (i.e.,\(q_{1}\)) carries over to period 2. Otherwise, a new quality shock \(q_{2}\) is realized. (6) Finally, the total utility is determined and observed by all agents.

Solving the model by backward induction, we see that, in period 2, the politician has no incentive to behave well and therefore, appropriates the maximum amount of rents \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\), implying zero targeted transfers to all groups of agents: \(T_{2}^{P*} = T_{2}^{M*} = T_{2}^{R*} = 0\). Equations (4), (5), and (6) imply that voters are clearly better off with a more competent (high q) politician, as this gives them more utility in period 2. Thus, they use elections as a mean of reappointing competent politicians and ousting incompetent ones, taking into account their observed utility in period 1 and knowing that the opponents’ expected quality on Election Day is \(E(q) = 0\).Footnote 12 We now describe how this takes place and how it shapes politicians’ incentives in period 1.

2.1.1 The optimal voting behavior and the utility targets

In order to describe how the politicians’ decisions in period 1 affect the probability of reelection, we need to describe optimal voting behavior. In period 2, since \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\) and \(T_{2}^{P*} = T_{2}^{M*} = T_{2}^{R*} = 0\), the welfare of agents in the three groups is as follows:

where \(q_{2}^{\prime } = p_{I} q_{1} + (1 - p_{I} )q_{2}\). This is because, if the incumbent of the first period gets reelected the quality shock from period 1 (\(q_{1}\)) carries over to period 2, whereas if a new politician is elected a new quality shock (\(q_{2}\)) is realized. Since all politicians implement the same post-election budget, the only reason voters care about who gets reelected is that politicians’ qualities vary. As seen from period 1, the expected quality of the politician elected in period 2 is:

This expression follows because the expected quality of a new politician is zero on average, i.e., \(E_{1} (E_{2} q_{2} ) = E_{2} q_{2} = 0\). Thus, the voters want to reelect the incumbent if and only if their estimate of the politician's quality at the end of period 1 is positive, that is, if and only if \(E_{1} q_{1} > 0\). Since in our model δ M > δ R + δ P , the pivotal group of voters is the group of the middle class (M). Thus, we further proceed by examining how the preferences of this specific group shape the actions of the politician.

More precisely, to form a Bayesian estimate of the expected quality of the incumbent, the middle-income voters use information on the observed utility of the first period \(U_{1}^{M}\) and their knowledge about the incumbent’s equilibrium budget strategy. The equilibrium budget strategy of the incumbent is \(\tilde{u}_{1}^{M} = (1 - \bar{\tau })y_{M} + \tilde{T}_{1}^{M}\). Subtracting the equilibrium budget strategy (\(\tilde{u}_{1}^{M}\)) from Eq. (5), we get:

The last equality makes use of the fact that in equilibrium, \(T_{1}^{M} = \tilde{T}_{1}^{M}\). Equation (12) shows that voters can infer the sum of the two shocks using their knowledge of the equilibrium. However, they are unable to decompose those two shocks and, therefore, to infer the quality of the politician. A rational voter can solve the resulting signal extraction problem and estimate that:

Based on Eq. (13), we conclude that the incumbent politician will be reelected if the realized utility of the middle-income agents exceeds the budget-related utility that the voters expect the incumbent to deliver in equilibrium, that is, if and only if \(U_{1}^{M} - \tilde{u}_{1}^{M} > 0\). Using Eq. (12), we can restate this criterion as \(q_{1} + \mu_{1} > \tilde{T}_{1}^{M} - T_{1}^{M}\). Having assumed that \(\mu_{1}\) follows a Bernoulli distribution with P(−1/2) = P(1/2) = 1/2 and that \(q_{1}\) follows a uniform distribution over \(\left[ { - \frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2}} \right]\), we get that the summation of \(q_{1}\) + \(\mu_{1}\) follows a uniform distribution over \([ - 1,1]\). Consequently, the probability of reelection as perceived by the incumbent is

Equation (14) shows that the reelection probability is increasing in budgetary transfers directed to the middle class. Therefore, the incumbent has an incentive to select the allocation of tax revenues so as to increase redistribution towards this specific group of individuals.

2.1.2 The budget allocation in equilibrium

Combining Eqs. (7) and (14) with the government’s budget constraint, we conclude that the equilibrium values for \(\left\{ {T_{1}^{P} ,T_{1}^{M} ,T_{1}^{R} ,r_{1} } \right\}\) are those that maximize incumbent’s inter-temporal utility:

subject to the first period’s budget constraint \(\delta_{P} T_{1}^{P} + \delta_{M} T_{1}^{M} + \delta_{R} T_{1}^{R} + r_{1} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\) and the rent extraction decision of the second period (i.e., \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\)). Then, Appendix 1-Supplementary material shows:

Proposition 1 The incumbent generates a rational political budget cycle. The post-election result is \(T_{2}^{P*} = T_{2}^{M*} = T_{2}^{R*} = 0\) and \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\) . The pre-election result is \(r_{1}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y} - \delta_{M} T_{1}^{M*}\) (which is smaller than \(r_{2}^{*}\) for \(T_{1}^{M*} > 0\)) and \(T_{1}^{M*} = \frac{{\bar{\tau }\bar{y}\beta \ln (E + r_{2}^{*} ) - 2\delta_{M} }}{{\delta_{M} \beta \ln (E + r_{2}^{*} )}}\) (which is positive if \(\bar{\tau }\bar{y}\beta \ln (E + r_{2}^{*} ) > 2\delta_{M}\)). Finally, \(T_{1}^{P*} = T_{1}^{R*} = 0\).

Thus, during the pre-electoral period the incumbent has an incentive to reduce extracted rents and correspondingly to increase the transfers to the middle-income voters in order to convince them of their quality and thereby remain in office for a second period. However, since pre-electoral transfers are directed exclusively to the middle-income group and not to the low-income group of agents, elections fail to reduce after-taxes-and-transfers income inequality and consequently to increase the actual amount of redistribution.Footnote 13

Corollary 1 Since pre-election transfers are strictly targeted to the middle-income group they do not reduce the after-taxes-and-transfers Gini coefficient.

2.2 Fiscal redistribution when the election takes place in the shadow of revolution

In this section, we solve the model for the case of a newly established democracy. More precisely, we assume that during the first years of a political transition, wherein democracy is not “the only game in town”, citizens have an option to revolt against the incumbent if the latter fails to ensure a minimum amount of competence. In this case, the survival of the democratic regime cannot be taken as given, since there is a probability of collapse and a consequent reversal to other forms of governance.Footnote 14

The timing of the events in this case is as follows: (1) At the beginning of period 1, a balanced budget \(\left\{ {T_{1}^{P} ,T_{1}^{M} ,T_{1}^{R} ,r_{1} } \right\}\) is implemented. (2) The two random shocks \(q_{1}\) and \(\mu_{1}\) are realized. As before, the random shocks are not observed directly by anyone, but all agents are able to observe total utility. (3) At the end of the first period, elections take place, and the voters either reelect the incumbent politician or elect a new one. (4) After elections, the citizens decide whether to revolt or not. More precisely, if the incumbent politician fails to convince the citizens that his quality exceeds a minimum amount of competence, a revolution takes place and the democratic regime collapses with probability \(p_{R}\). (5) In period 2, regardless of whether the democratic regime survived or not (in stage 4), the official implements a balanced budget \(\left\{ {T_{2}^{P} ,T_{2}^{M} ,T_{2}^{R} ,r_{2} } \right\}\). (6) A new luck shock \(\mu_{2}\) is realized. If the democratic regime has survived and the incumbent of the first period is reelected, the quality shock from period 1 (i.e., \(q_{1}\)) carries over to period 2. Otherwise, a new quality shock \(q_{2}\) is realized. (7) Finally, total utility is determined and observed by all agents.

Again, solving the model by backward induction, we see that in period 2 the official (whether democratically elected or not) has no incentive to behave well. Therefore, he extracts the maximum amount of rents \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\), implying zero targeted transfers to all groups of agents: \(T_{2}^{P*} = T_{2}^{M*} = T_{2}^{R*} = 0\). As in Sect. 2.1, Eqs. (4), (5), and (6) imply that citizens are clearly better off with a more competent (high q) politician, as this increases their utility in period 2. Thus, they use elections as a mean of reappointing a competent politician and throwing the incompetent ones out of office. However, in the case of a new democracy, the citizens have one additional option in order to ensure a minimum amount of competence (i.e., quality that equals to \(\bar{q}\)), which is to revolt and oust the incumbent from office. We now describe how this takes place and how it shapes politicians’ incentives in period 1.

2.2.1 The optimal voting behavior and the utility targets

Since δ M > δ R + δ P , when elections take place, the pivotal group of voters remains the middle-income group (M). Following the rationale developed in Sect. 2.1.1, the criterion under which the middle class votes for the incumbent is \(U_{1}^{M} - \tilde{u}_{1}^{M} > 0\), which generates the following probability of reelection as perceived by the incumbent: \(p_{I} = \frac{1}{2}[1 + (T_{1}^{M} - \tilde{T}_{1}^{M} )]\). Therefore, the reelection probability in new and established democracies is identical, and it increases by the amount of transfers (\(T_{1}^{M}\)) directed to the middle-income group.

2.2.2 The threat of revolution

Following the rationale of the relevant theoretical literature, we assume that in newly established democracies' elections also act as a public signal of government’s popularity. This helps the citizens to solve potential problems of collective action and to revolt against the incumbent whenever a high level of anti-regime sentiments emerges (see, e.g., Fearon 2011; Little 2012; Little et al. 2015). Therefore, we assume that at the end of the first period (after elections are held), the citizens from the middle-income (M) and the low-income (P) groups decide whether to revolt or not.Footnote 15 More precisely, citizens revolt whenever they estimate that the quality of the incumbent at the end of the first period is negative and below a threshold quality level \(\bar{q}\). That is, if and only if \(E_{1} q_{1} < \bar{q} < 0\). This condition is binding only in the case of the low-income citizens. That is because middle-income citizens determine the probability of reelection by their votes and, therefore, they demand even higher (i.e., a positive) competence at the end of the first period in order to reelect the incumbent.Footnote 16 Thus, we focus on the low-income group of agents and examine how the threat of potential revolution shapes a politician’s incentives in period 1.

As in Sect. 2.1.1, in order to form a Bayesian estimate of the expected quality, citizens rely on the observed utility of the first period \(U_{1}^{P}\) and their knowledge about the incumbent’s equilibrium budget strategy. The equilibrium budget strategy of the incumbent is \(\tilde{u}_{1}^{P} = (1 - \bar{\tau })y_{M} + \tilde{T}_{1}^{P}\). Subtracting equilibrium budget strategy (\(\tilde{u}_{1}^{P}\)) from Eq. (4) we get:

Equation (16) shows that voters can infer the sum of the two shocks using their knowledge of the equilibrium. However, they are unable to decompose them and, therefore, to infer the quality of the politician. A rational citizen can solve the resulting signal extraction problem and estimate that:

Based on Eq. (17), we conclude that low-income citizens will decide to revolt if \(\frac{1}{4}(U_{1}^{P} - \tilde{u}_{1}^{P} ) < \bar{q}\). Using Eq. (16), we can restate this criterion as: \(q_{1} + \mu_{1} < \tilde{T}_{1}^{P} - T_{1}^{P} + 4\bar{q}\), where q 1 + μ 1 follows a uniform distribution over \([ - 1,1]\). Consequently, we get the following probability of revolution as perceived by the incumbent:

Assuming that whenever a revolution takes place it is successful and the democratic regime collapses, we derive the following probability of democratic regime survival:

Equation (19) shows that the probability of a democratic regime’s survival is increasing in income transfers to the low-income group of individuals (\(T_{1}^{P}\)). Thus, when “elections take place in the shadow of revolution”, the incumbent has an incentive to increase redistribution towards the poorer agents. This strategy allows the incumbent to stabilize the political regime and consequently to increase the probability of remaining in office. In other words, in a relatively new democracy, focusing solely on the preferences of the middle-income group is not a sufficient condition for continuing in office, since the incumbent also faces a potential threat of revolution from the low-income group. Therefore, the total utility of the incumbent in the case of a new democracy takes the following form:

where \(p_{I}\) is the probability of the incumbent being re-elected and \(p_{D}\) is the probability of the democratic regime surviving.

2.2.3 The budget allocation in equilibrium

Combining Eqs. (14), (19), and (20) with the government’s budget constraint, we conclude that the equilibrium values for \(\left\{ {T_{1}^{P} ,T_{1}^{M} ,T_{1}^{R} ,r_{1} } \right\}\) are those that maximize the incumbent inter-temporal utility in the case of a newly established democracy:

subject to the first period’s budget constraint, \(\delta_{P} T_{1}^{P} + \delta_{M} T_{1}^{M} + \delta_{R} T_{1}^{R} + r_{1} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\), and the rent extraction decision of the second period (i.e., \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\)). Equation (21) shows that in a new democracy the incumbent should accommodate the needs of the low and middle-income groups (\(T_{1}^{P} and T_{1}^{M} )\) in order to maximize its probability of remaining in office. This is because transfers directed to the low-income group of agents (\(T_{1}^{P}\)) serve as a policy instrument of democratic consolidation, whereas transfers directed to the middle-income group (\(T_{1}^{M}\)) represent a policy instrument that affects the reelection probability when elections are held. Then, Appendix 1-Supplementary material shows:

Proposition 2 The incumbent generates a rational political budget cycle. The after-election result is \(T_{2}^{P*} = T_{2}^{M*} = T_{2}^{R*} = 0\) and \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\) . The pre-election result is \(T_{1}^{P*} = \frac{1}{{\delta_{P} }}\bar{\tau }\bar{y} - \frac{{\delta_{M} }}{{\delta_{P} }}T_{1}^{M*} - \frac{4}{{\beta \ln (E + r_{2}^{*} )}}\) (which is positive for \(T_{1}^{M*} < \frac{1}{{\delta_{M} }}\bar{\tau }\bar{y} - \frac{{4\delta_{P} }}{{\delta_{M} \beta \ln (E + r_{2}^{*} )}}\)) and \(T_{1}^{M*} = \frac{1}{{\delta_{M} }}\bar{\tau }\bar{y} - \frac{{\delta_{P} }}{{\delta_{M} }}T_{1}^{P*} - \frac{4}{{(1 - 4\bar{q})\beta \ln (E + r_{2}^{*} )}}\) (which is positive for \(T_{1}^{P*} < \frac{1}{{\delta_{P} }}\bar{\tau }\bar{y} - \frac{{4\delta_{M} }}{{\delta_{P} (1 - 4\bar{q})\beta \ln (E + r_{2}^{*} )}}\)). Finally, \(r_{1}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y} - \delta_{P} T_{1}^{P*} - \delta_{M} T_{1}^{M*}\) (which is smaller than \(r_{2}^{*} = \bar{\tau }\bar{y}\) for any positive \(T_{1}^{P*} ,T_{1}^{M*}\)).

Thus, during the pre-electoral period the incumbent may reduce extracted rents and correspondingly increase income transfers directed to the middle and to the low-income groups of citizens in order to convince the voters of his or her quality and, therefore, to remain in office for a second period.

Corollary 2 Every combination of \(T_{1}^{M*}\) and \(T_{1}^{P*}\) that ensures \(T_{1}^{P*} > 0\) directs an amount of total transfers to the low-income group of agents, thus reducing the after-taxes-and-transfers Gini coefficient.

Therefore, in a newly established democracy, pre-election transfers to the low-income group of agents can be an optimal solution for the incumbent. In this case, elections exert a negative impact on after-taxes-and-transfers income inequality.

3 Econometric analysis

Our model highlights that uncertainty regarding the type of the political regime alters significantly the pre-election strategy of the incumbent, with an immediate effect on the redistributive implications of fiscal policy. In this section, we examine whether the electoral effect on income inequality and budgetary redistribution varies between new and established democracies. Then, we attempt to establish and clarify the importance of political instability—especially in the first years of a democratic transition—as a determinant for the incumbent’s optimal fiscal policy strategy.

3.1 Dataset and variables

Following previous studies, we measure income inequality by the Gini coefficient (index) of income distribution. The Gini coefficient ranges from a minimum value of zero, when the incomes of all individuals are the same, to a maximum of one in a population when all the wealth is concentrated in a single individual. However, a primary concern when employing income inequality estimates in cross-country empirical research is data comparability, both over time and across countries. For this reason, our preferred data are obtained by the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID), developed by Frederick Solt (2009). The SWIID maximizes the comparability of income inequality statistics for the largest possible sample of countries and years, namely, for 174 countries for as many years as possible from 1960 to 2010. For the construction of the dataset, Solt (2009) employed a customized missing-data algorithm to standardize Gini estimates from all major existing resources of income inequality data (e.g., Luxembourg Income Study, World Income Inequality Database). An important advantage of the SWIID is that it provides Gini estimates before taxes and transfers (market income), as well as after-taxes-and-transfers (net income). They are denoted as gini_market and gini_net, respectively. Furthermore, the percentage change between gini_market and gini_net gives us an estimate of fiscal redistributionFootnote 17:

This decomposition of income inequality, before and after-taxes-and-transfers, has the advantage of allowing us to identify the fiscal policy instruments that are exploited by incumbents before elections. Consistent with our theory, if incumbents in unconsolidated democracies target income transfers pre-electorally to low-income groups, then we would expect net inequality (gini_net) to decline and budgetary redistribution (redist) to increase. This is consistent with the simple observation that a small income increase for a high-income person leads to an increase in inequality, but that the same income increase for a low-income person results in a reduction in inequality (see, e.g., Corvalan 2014).

We expect pre-electoral changes in taxes and transfers to show up as yearly fluctuations in the variables gini_net and redist for three reasons. First, according to the literature, fiscal policy cycles exist and they are very intense in developing countries and new democracies, making highly likely their translation into econometrically verifiable cycles in aggregate income inequality. Second, if these cycles emerge as a result of increases in cash transfers to low-income agents, as predicted by our theory, we expect an immediate effect on the after-taxes-and-transfers income inequality (gini_net). It should be noted that other fiscal policy instruments, such as public spending on education or projects that promote public employment, can also affect the income distribution. However, their effect could be manifested mainly through changes in market inequality (see Besley and Coate 1991; Alesina et al. 2000). More importantly, these spending components have a long-run effect on the income distribution (e.g., public spending on education), and they are more difficult to target towards the poorer segments of the society. Therefore, investigating their short-run effects on income inequality is a more ambitious research plan. Third, as we discuss in more detail in Sects. 3.2 and 4.4.1, our empirical strategy takes into account the timing of elections—year within the term and month within the year—in order to identify properly the severity of pre-electoral fiscal changes that subsequently can be translated into changes in income inequality.

It is worth noting that the SWIID provides estimates of uncertainty for each country-year observation of the income inequality data. Closely related to this point, Solt (2009) notes that Gini estimates are often “thin” in the early years that a country enters into the dataset. For this reason, observations for the variable redist are restricted to after 1975 for most of the advanced countries and to after 1985 for most countries in the developing world, although the components of redist, namely gini_market and gini_net, are available prior to these years. Taken this into account, we opt for limiting our sample for the variables gini_market and gini_net to the country-year observations for which the variable redist is available.Footnote 18

Regarding the main variable of interest, it should be stressed that the electoral-cycle models assume competitive elections. To this end, we restrict our sample further to those observations for which the variable POLITY2 from the Polity IV Project (Marshall et al. 2013) receives positive values and the variables Liec and Eiec from the Database on Political Institutions (DPI) (Beck et al. 2001) receive values equal to or greater than six.Footnote 19 Following the majority of the empirical literature, we capture the effect of elections by constructing a dummy variable (elec) that takes the value of one in an election year and zero otherwise. We include in our sample legislative elections for countries with parliamentary political systems and presidential elections for countries with presidential systems. Election dates were collected from the DPI and complemented, when needed, with information from various sources (e.g., the African Elections Database).

To ensure robust econometric identification, our analysis employs a number of covariates that are expected to affect income inequality and fiscal redistribution programs. In particular, we control for GDP per capita (gdppc) and its squared term (gdppc^2), obtained from Penn World Tables, to test for the hump-shaped relation between economic development and inequality, as described by Kuznets (1955). Moreover, from the same database we obtain an index of human capital per person (human capital), which was constructed based on years of schooling (Barro and Lee 2013) and returns to education (Psacharopoulos 1994). We expect an increase in the human capital index to be negatively related to income inequality (see, e.g., Li et al. 1998). In addition, we employ the dependency ratio of the population (dependency), which is measured as the percentage of the population younger than 15 years or older than 64 to the number of people of working age between 15 and 64 years. This variable allows us to control for demographic influences on the structure of social spending and fiscal redistribution (see, e.g., Galasso and Profeta 2004; von Weizsäcker 1996). The next control is population density (population density), defined as the population divided by land area in square kilometers. Larger share population densities ensure economies of scale in the provision of public goods and, therefore, more fiscal redistribution for a given level of spending (see, e.g., Alesina and Wacziarg 1998). The model also includes the inflation rate (inflation), because low-income households are likely to be relatively more vulnerable to price increases than others (see, e.g., Albanesi 2007). Data on dependency, population density and inflation are obtained from World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). Finally, we use the KOF index of economic globalization (global), developed by Dreher (2006), to test the potential effect of economic globalization on income redistribution and income inequality (see, e.g., Rodrik 1997, 1998).Footnote 20

3.2 Empirical specification

To test the theoretical predictions derived in Sect. 2, we start our analysis from the following specification:

where Y it is the outcome of interest, which will either be income inequality (gini_market and gini_net) or income redistribution (redist) in country i and year t. Moreover, Z it includes the covariates described above, except the election dummy, μ i represents a fixed country effect and ε it is the error term. In line with many previous studies, the lagged value of the dependent variable, Y it−1 , is entered on the right-hand side of the estimated equation to capture the persistence in income inequality (see, e.g., Chong et al. 2009; Amendola et al. 2013). A problem that arises, though, is that estimates of this empirical specification produce extremely high autoregressive error structures. Moreover, the Maddala and Wu (1999) and Choi (2001) unit root tests, indicate that the null hypothesis of panel unit root can clearly be rejected only for the first differences of the income inequality and income redistribution variables. Table A1 in the Supplementary material presents the results.

To deal with non-stationary data Eq. (23) is specified in first differences. In our preferred specification we can now introduce the main variable of interest that allows us to capture the influence of elections. Hence, we end up estimating the following equation:

where the ‘\(\Delta\)’ prefix indicates that the first difference of a variable is taken, and elec is an election dummy. It should be noted that first differencing all variables, except the election dummy, is a common approach applied in the literature, which allows putting more structure on the data for the identification of the pre-electoral effect (see, e.g., Levitt 1997; Mechtel and Potrafke 2013). It is worth noting that by taking first differences we eliminate time-invariant country effects, but not time-fixed effects. Hence, λ t in Eq. (24) represents a fixed period effect. Finally, w k represents a set of regional dummy variables allowing us to control for regional differences.Footnote 21

Moving one step forward, Eq. (24) is modified to test whether systematic differences between new and established democracies exist. In particular, we consider the first four completive elections after a shift to a democratic regime, indicated by the first year of a string of uninterrupted positive POLITY values, as elections held in a new democracy (see Brender and Drazen 2005). Thus, we create two new variables elec_new and elec_old to replace elec, for elections held in new and established democracies, respectively:

Among the 362 elections in the sample, 30 % (108) were held in new democracies. According to our theoretical analysis, in new democracies incumbent politicians take into account the probability of a democratic regime’s collapse in addition to their own reelection probability, allocating resources to a broad group of agents (which also include low-income agents). Therefore, we would expect the variable elec_new to exert a negative impact on income inequality after taxes and transfers (gini_net) and a positive impact on income redistribution policies (redist). In established democracies, though, where pre-electoral policies are strictly targeted to the middle class within which the “pivotal” group of voters is located, the distributional effect of elections should be neutral.

Another interesting issue concerning this literature is the timing of elections. As argued by Heckelman and Berument (1998), the timing of elections in parliamentary democracies may not be exogenous to government policy, but is chosen strategically by the incumbent when economic conditions are favorable, raising the problem of reverse causation. Of course, elections may also be called early by an opposition parliamentary coalition owing to a deterioration of economic conditions that create a majority for replacing the government. Besides the obvious identification issue, one might argue that in a late election the incumbents have ample opportunity to exploit fiscal policy instruments compared to the case of an election being called earlier. It should be noted that many researchers have provided evidence for systematic differences between early and late elections (see, e.g., Shi and Svensson 2006; Vergne 2009; Ehrhart 2013). Therefore, we have reasons to believe that changes in fiscal policy in predetermined elections, which can be more severe and more easily identified, can be reflected much easier in yearly fluctuations in the Gini coefficients. To address this issue—to the degree possible—we distinguish between endogenous and pre-determined elections following the approach of Brender and Drazen (2005). More precisely, we look at the constitutionally determined election interval and we define as predetermined those elections that are held during the expected year of the constitutionally fixed term. Hence, we split the election dummy elec_new (elec_old) into the variables elec_new_pred (elec_old_pred) and elec_new_endod (elec_old_endog) for the predetermined and endogenous elections, respectively, held in new (old) democracies. Hence, we modify Eq. (25) in the following way:

Among the 108 (254) elections held in new (old) democracies, 86 (177) are classified as predetermined. Our unbalanced cross-country time series dataset includes observations for 65 countries over the 1975-2010 period. Appendix 2-Supplementary material lists all countries and years of our dataset. It further illustrates which countries of our sample are classified as developed economies and/or new democracies.Footnote 22 Moreover, the Data Appendix-Supplementary material provides definitions, data sources and descriptive statistics of all variables used in our estimations.

Regarding the econometric specification, the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable on the right-hand side introduces a potential bias in our estimates by not satisfying the strict exogeneity assumption of the error term ε it . One solution could be the adoption of the GMM estimator, developed for dynamic panel data (e.g., Arellano and Bond 1991; Blundell and Bond 1998). However, these methods yield consistent estimates in small T, large N panels. Our sample contains 65 countries, but when these are split between developed and developing countries we actually are left with 22 and 43 cross-sections, respectively, raising issues of consistency for the GMM method. Still, as it is analyzed in the literature, the estimated bias of this formulation is of order 1/T, where T is the time length of the panel, even as the number of countries becomes large (see, among others, Nickell 1981). The average time series length of our panel is close to 22, 29, and 18 observations for the whole sample, the developed and developing countries, respectively, likely making the bias negligible. Therefore, we estimate Eqs. (24), (25), and (26) employing the OLS estimator with time and regional fixed effects.

4 Results

4.1 Baseline results

Our baseline results are reported in Table 1. In columns (1)–(3) we report the estimates of Eq. (24). As can be seen, the variable elec in column (2) is negative and significantly related to the variable Δgini_net at the 10 % level. Hence, we have some weak evidence that net income inequality declines near elections. Next, in columns (4)–(6) we estimate Eq. (25) splitting the election dummy into the variables elec_new and elec_old for elections in new and old democracies, respectively. Estimates for the variable elec_old indicate that pre-electoral fiscal changes in established democracies do not have any significant distributional implications. For the new democracies, our findings differ considerably. In particular, in column (5) the variable elec_new is negatively related to net income inequality at the 1 % level. Given that in column (4) market inequality does not seem to be affected, this policy intervention in new democracies seems to act as a means of redistributing income to the poorer segments of the society. Indeed, in column (6), the pre-electoral change in market inequality owing to taxes and transfers is positive and statistically significant at the 5 % level.Footnote 23

Next, in columns (7)–(9), we proceed to the estimation of Eq. (26), where our election dummies distinguish between pre-determined and endogenous elections held either in new or in old democracies.Footnote 24 Once again, we do not obtain any statistically significant effect for elections held in established democracies. Moreover, for new democracies, results for the variable elec_new_pred seem to be consistent with those obtained in the previous specification for the variable elec_new. This suggests that only in predetermined pre-electoral campaigns in new democracies, fiscal policy manipulation promotes fiscal redistribution.Footnote 25 This is the expected result, since fiscal policy changes in a late election, which can be more severe and/or more easily identified than in the case of an early election, are reflected in changes in fiscal redistribution.

These empirical findings are consistent with our theoretical predictions as well as with previous studies on the same subject (see, e.g., Brender and Drazen 2008, 2009). More precisely, consistent with our theory, in new democracies where an election can be held “in the shadow of revolution”, fiscal redistribution can act as a device to consolidate democracy. Our findings are also in accordance with those of Brender and Drazen (2008, 2009), who suggest that in new democracies pre-electoral shifts in fiscal policy do not serve to improve reelection prospects. Instead, the same authors provide evidence that newly established regimes are almost three times more likely to collapse in election years than in non-election years. They conclude that incumbent politicians in new democracies provide benefits mostly because they seek to provide a signal that “democracy works” and therefore prevent a reversion to autocracy at a time of high vulnerability.

4.2 Economic development, regime maturity, and elections

Several papers in the literature have reported evidence that electoral cycles are driven, or at least amplified, by the experience of less developed countries (see, e.g., Klomp and de Haan 2013b; Streb and Torrens 2013). According to Schuknecht (1996), fiscal manipulation is more likely in developing countries because checks and balances are weaker, allowing for greater political discretion over policy instruments. Moreover, Shi and Svensson (2006) argue that information asymmetries between voters and politicians regarding the competence level of the latter—a crucial assumption of PBC models—are more pronounced in developing countries. According to this view, as the number of voters who fails to distinguish election-motivated fiscal policy manipulations from incumbent competence increases, the more the incumbent can benefit from opportunistic behaviors before an election. In contrast, in developed countries where well-informed voters can evaluate more accurately a government’s performance (competence), pre-electoral fiscal manipulation seems to be punished rather rewarded at the polls (see, e.g., Peltzman 1992; Brender and Drazen 2008).

Therefore, our next task would be to access if the level of development can overshadow the observed systematic differences between new and established democracies. To this end, in Table 2 we re-estimate the specification in Eq. (26), as in columns (7)–(9) of Table 1, after splitting the sample between developed and developing countries. With respect to developed countries, the coefficient of the variable elec_new_pred is negatively and significantly related to market income inequality, which contributes to the significant reduction of net inequality. However, this change does not seem to emerge from the tax-transfer system, leaving our measure of fiscal redistribution in column (3) unaffected. It is worth mentioning, though, that we cannot make strong inferences about this result, since we have only eight election observations for this variable. Results for the other three electoral variables in columns (1)–(3), namely elec_new_endog, elec_old_pred and elec_old_endog, do not reveal any other significant effect. Turning to developing countries, as can be seen in columns (4)–(6) of Table 2, results for the variable elec_new_pred are consistent with those obtained for the whole sample in Table 1. Concerning the magnitude of the effect of predetermined elections in new democracies, we observe in column (6) an increase in the change of fiscal redistribution by 0.88 points. Given that the mean value of Δredist in the sample is 0.034 points (with a standard deviation of 1.7 points), it is clear that this effect is quantitatively sizable. Results for the rest electoral variables in columns (4)–(6) are statistically insignificant, indicating that the age of the regime and not the level of development is what matters for our findings.

Table A2 in the Supplementary material presents an alternative specification where we split the sample, not the election dummy, between new and established democracies in developed and developing countries. In all sub-samples of Table A2 we apply the simple specification of Eq. (24), where additionally we split the election dummy between predetermined (elec_pred) and endogenous elections (elec_end) to account for the potential endogeneity of the electoral process.Footnote 26 Moreover, given that the average length of the panel in some cases drops below 11, we opt for applying Bruno’s (2005) bias corrected least squares dummy variable estimator for dynamic panel data models with small N. Our results seem to verify those obtained in Table 2.

4.3 Regime’s stability and fiscal redistribution around elections

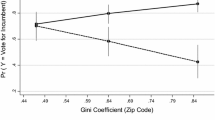

According to our theoretical analysis, uncertainty regarding the type of the political regime is the driving force of our results. So far, this uncertainty has been measured by the age of the democracy. In this section, we attempt to corroborate this theoretical prediction by augmenting our analytical specification in Eq. (26) with proxies for political instability. To measure regime (in)stability, we employ two measures of civil unrest as provided by the Social, Political, and Economic Event Database (see Nardulli et al. 2011).Footnote 27 The database reports daily observations for a range of variables (e.g., coups, anti-regime protests), which we collapse into country-year observations. From the alternatives provided, we choose the variables state repression and state violence as the two most relevant for our purpose. A score of zero on these intensity measures indicate a year with no reported unrest, whereas larger values reflect greater levels of instability. Hence, we augment Eq. (26) with interaction terms of the electoral variables (e.g., elec_new_pred × Δinstability), where Δinstability refers to the first difference of the two proxy variables described above. For brevity, in Table 3 we report estimates only for the main outcome measure of interest, namely the variable Δredist. In columns (1)–(3), the estimates refer to the whole sample, developed and developing countries, respectively, when state repression is used as the proxy for political instability. Columns (4)–(6) have the same structure when state violence is entered alternatively.

As can be seen in Table 3, once again, the variable elec_new_pred enters with a positive and statistically significant coefficient in our estimates, but only for the case of developed countries in columns (2) and (5). Moreover, in columns (1)–(3) the variable Δstate repression is related insignificantly to fiscal redistribution. Interestingly, it becomes statistically significant in columns (1) and (3) when interacted with the variable elec_new_endog. In columns (4)–(6), the variable Δstate violence is negatively related to fiscal redistribution only in the specification for the whole group of countries. More importantly, the interaction terms elec_new_pred × Δstate violence and elec_old_pred × Δstate violence are positive and statistically significant in columns (4) and (6). In contrast, in column (5) the respective variables for the sample of developed countries have a neutral effect on fiscal redistribution. Therefore, political instability seems to bolster fiscal redistribution in pre-electoral periods in the case of developing countries, and especially for those countries within this sample that are considered to be new democracies. In particular, in young democracies in the developing world, as expected, an increase in the variable Δstate violence seems to intensify the already positive and statistically effect of the variable elec_new_pred on fiscal redistribution. For developing “old democracies” the electoral variable elec_old_pred remains statistically insignificant, and for reasonable values of the variable Δstate violence so does the overall effect of elections. However, this interesting finding might reflect that in some special cases the path to consolidation might not be completed the first years of the democratic transition.

4.4 Sensitivity analysis

In this sub-section, we explore the robustness of the results obtained in Table 3 where the analytical specification of Eq. (26) is augmented to provide evidence that regime instability matters for the observed electoral cycles. In our first robustness test, we employ an alternative electoral indicator that allows us to control for differences in election dates across as well as within countries. Moreover, we check if our results are influenced by outlier observations.

4.4.1 Weighted electoral indicator

Until now, in order to capture the effect of elections, following the majority of the literature, the election dummy is equal to one in the year of the election, no matter when during the year the election actually was held. This can be problematic, since if elections took place early in the year then the election dummy can be capturing primarily post-electoral effects. In contrast, if the election took place late in the year, then the dummy indeed can capture more accurately the fiscal changes before the election (see, e.g., Brender and Drazen 2005; Vergne 2009). For that latter case, one could also argue that Gini coefficients can gauge more effectively the fiscal effects of elections. To address this issue, we follow the approach of Franzese (2000), redefining our electoral variable to give more weight to elections that took place later during the year. Therefore, our new pre-electoral variable (preel) takes the value of x/12; with x denoting the month the election is held. In order to reproduce the specification in Table 3, we split the variable preel into preel_new_pred (preel_new_end) and preel_old_pred (preel_old_end), for predetermined (endogenous) elections in new and old democracies, respectively.

As can be seen in Table 4, our most important finding that state violence during predetermined elections in developing countries reinforces fiscal redistribution remains unaffected. Interestingly, the interaction term preel_old_pred × Δstate violence becomes negative and statistically significant at the 5 % level in column (5). Hence, our findings indicate that instability around predetermined elections weakens fiscal redistribution in established developed democracies. However, since this empirical result is far from being robust we do not seek to provide any formal theoretical intuition.

4.4.2 Testing for outliers

Our next step is to perform two checks in order to ensure that our results are not influenced by outlier observations. First, to control for the effect of individual outliers, we use Cook’s distance, which measures the effect of deleting a given observation based on each observation’s residual in the regression and its leverage in the estimation process. Hence, according to the rule of thumb, we re-estimate our preferred specifications after dropping observations with a Cook’s distance larger than 4/n (where n the number of observations). Second, as already mentioned, the SWIID maximizes the comparability of available income inequality data, but incomparability remains and is reflected in the standard errors reported for each observation of variables gini_market, gini_net, and redist. The provision of standard errors is an additional advantage of the SWIID, because a large part of the remaining uncertainty of inequality data estimates can be taken into account. Therefore, in order to increase the reliability of our results further, we drop from regressions 10 % of the observations for which the variables gini_market, gini_net, and redist are associated with larger standard errors. In columns (1)–(6) of Table 5 we repeat the estimates of Table 3 after applying Cook’s criterion, whereas in the second half of Table 5 we alternatively drop from the same estimates the most noisy inequality data.

As can be seen, apart from the interesting finding that the interaction term elec_new_pred × Δstate repression is positive and significantly related to fiscal redistribution for the sample of developing countries in columns (3) and (6), our results are in line with those reported in Table 3.Footnote 28

To sum up, our results clearly support the link between pre-electoral redistribution and instability, especially when the latter is proxied by the intensity of state violence. Interestingly, our findings also reveal that in some special cases incumbents in developing “old democracies” might implement fiscal redistribution around elections, indicating that the path to consolidation might not be completed during the first years of the democratic transition. It should be noted that in Tables A3 and A4 of the Supplementary material, we perform the same robustness checks for the specification in Table 2 and results remain unaffected.

To close, we discuss our empirical findings concerning the rest of the covariates in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. First of all, the lagged dependent variable, as expected, bears a positive and significant coefficient in the large majority of our estimates. Moreover, we get some weak evidence that GDP per capita has the expected hump-shaped relationship with market inequality for the sample of developing countries. Moreover, in accordance with our theoretical priors, the coefficient of the variable Δpopulation_density is positive when significantly related to market inequality and fiscal redistribution. Next, Δinflation enters with a positive and significant coefficient in the empirical specification when net inequality is the dependent variable in Table 1, although this result does not seem to be robust throughout. Finally, the variable Δglobal has a positive (negative), though not robust, effect on net income inequality (fiscal redistribution) in developed countries.

5 Conclusions

Starting from Tullock (1974), a large strand of the political economy literature investigates the role of the threat of revolution in triggering democratic transitions (see, e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson 2000, 2006; Przeworski 2009; Aidt and Jensen 2014). However, most of these studies assume that de facto political power does not play a role in policy decisions after the transition to a democratic regime. This is because in a democratic regime all agents recognize elections as the one and only acceptable political decision mechanism and, hence, conflicts of interests are resolved strictly through voting. However, assuming that de facto political power vanishes just after the transition to democracy, and treating democratic elections as being self-enforcing, leaves unexplored a large number of interesting political issues related to the transition process. Moreover, history suggests that waves of democratization many times are followed by reverse waves to dictatorship (see, e.g., Huntington 1993), providing anecdotal evidence that a democratic regime, especially a new one, is far from being self-enforcing (see Fearon 2011 for a discussion on this issue).

Building on this rationale, the present paper investigates how the de facto political power—and the consequent threat of revolution—may affect implemented economic policies in democracies, especially during the first years of the transition. Our analysis suggests that in relatively stable democratic regimes, income transfers are targeted strictly to the middle class, in which the “pivotal” group of voters is located, leaving unaffected the distribution of income. However, in new democracies wherein fiscal policies also serve as a device for consolidating democratic regimes, incumbent politicians allocate resources to a broader group of agents, thereby boosting fiscal redistribution.

Our empirical results for a sample of 65 developed and developing countries over the 1975–2010 period support these theoretical predictions. In particular, our findings indicate that in countries characterized as young democracies, elections exert a positive and significant impact on fiscal redistribution, as measured by the reduction in market income inequality associated with taxes and transfers. Moreover, we find that the effect of elections is stronger when new democracies are characterized by relatively greater political instability, especially when the latter is proxied by state violence. Backed by strong empirical results, we contend that fiscal redistribution acts as a mean of consolidating a vulnerable democratic regime.

Notes

In support of this argument, Streb et al. (2009) show that electoral budget cycles are stronger in developing countries than in industrial countries.

More recently, Klomp and de Haan (2013b, c) provided evidence that the occurrence of a PBC is much stronger in developing counties and “young democracies”. However, Efthyvoulou (2012), using data for 27 EU member states from 1997 to 2008, finds that incumbent governments tend to manipulate fiscal policy in order to maximize their chances of being reelected. It is worth noting, though, that when Klomp and de Haan (2013d) employ a semi-pooled panel model to allow the impact of elections to vary across countries, they find no PBC in most countries.

We have to note that manipulation of the composition of fiscal policy seems particularly relevant in developed economies in which the incumbent may avoid deficit creation owing to the fear of voters’ disfavor (see, e.g., Brender and Drazen 2008).

It is frequently argued in the literature that only antidemocratic elites (e.g., military juntas and oligarchs) can pose serious threats in a newly established democracy (see Acemoglu and Robinson 2006). Nonetheless, empirical and anecdotal evidence strongly suggests that the support of the citizenry for the institutions of democracy cannot be taken for granted (see Linz and Stepan 1996). For instance, a few years after Brazil’s democratization, according to a Brazilian national survey published in February 1992, the poorest citizens were the least supportive of democracy.

The tension that surrounds pre-election campaigns in a newly established democratic regime is an important factor that contributes significantly to political instability. In many cases, it has been observed that periods around Election Day are the times of greatest vulnerability for democratic regimes (e.g., Bolivia 1978–1980; Nigeria 1993 and Pakistan 1977). Brender and Drazen (2007) provide empirical evidence that in “young democracies” the regime is almost three times more likely to collapse in election years than in non-election years.

Linz and Stepan (1996), summarizing the experience of the new democracies in southern Europe, suggest that the consolidation of democracy takes place only when ordinary citizens come to believe that democracy is superior to any other form of governance. Before that point, their pro-democratic feelings cannot be taken for granted.

The underlying assumption is that voters are ill informed about the finer details of public finance. This is analogous to the assumption in Lohmann (1998) that voters do not observe the implemented monetary policy directly.

That is, the luck shock (μ t ) follows a Bernoulli distribution with p(−1/2) = p(1/2) = 1/2.

These exogenous ego-rents (E) reflect the value attached to winning the elections and holding office (see Persson and Tabellini 2000, ch. 3.2, for more details on this).

This is because the quality shock of the opponent is drawn from a uniform distribution that is known to the voters.

We note that the tax rate (τ) is proportional to the income of each group, and it remains fixed at a level of \(\tau = \bar{\tau }\) in both periods.

Previous studies (e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson 2000, 2006; Aidt and Jensen 2014) suggest that threat of revolution is an important factor for democratization, but it disappears when the regime becomes democratic. Building on this rationale, our model investigates whether the threat of revolution may affect the implemented economic policy in democratic regimes, especially during the first years of the transition.

Several studies suggest that the consolidation of democracy takes place only when ordinary citizens come to believe that democracy is superior to any other form of governance (see, e.g., Linz and Stepan 1996; Brender and Drazen 2007). Before that point, the pro-democratic feelings of the masses cannot be taken for granted.

As in Sect. 2.1, middle class citizens vote for the incumbent only if their estimate of his or her quality at the end of the first period is positive (i.e., if E 1 q 1 > 0).

Alternatively, if we use the difference between market-income and net-income Gini indices, the results remain essentially the same.

It is worth noting that in Sect. 4.4.2 we attempt to limit further the uncertainty that can be related to the Gini estimates.

A value of six on the seven-point legislative and executive indices of electoral competition indicates that multiple parties did win seats, but the largest party can receive more than 75 % of them. However, our sample and results remain essentially the same if we assign the highest score on each of these two indices, which specifies multiparty elections and that the largest party won less than 75 % of the seats.

We have also attempted to include in our model a series of other control variables, such as population size, population growth, foreign aid, voter turnout, variables on political constraints, and others. However, none of these variables had a significant effect on income inequality/redistribution, and owing to other concerns as well (correlation of control variables, reduction of sample size), we do not include them in our estimates. Results are available upon request.

The countries of our sample are distributed in the following regions: the Caribbean, Central Asia, East Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, Middle East and North Africa, North America, the Pacific, Sub-Saharan Africa, Western Europe, and North America (including Australia and New Zealand). It is worth noting that the F-test results for the time and regional fixed effects (available upon request) are in general statistically significant.

The sample size was limited by the availability of income inequality data, as well as by the competitiveness of elections for those country-year observations for which income inequality data were available. It should further be stressed that our sample includes countries for which we have at least one electoral observation available over a 5-year period. The results remain robust, though, when we restrict the sample to those countries for which more than ten observations are available.

Moreover, pre-electoral manipulation of fiscal policy, and its distributional implications, may depend significantly on the nature of the constitutional rules. As outlined by the relevant literature, politicians in proportional and parliamentary democracies are more prone to promote broad-based policies, such as welfare spending, while in majoritarian and presidential regimes this holds for geographically targeted expenditures (see, e.g., Milesi-Ferretti et al. 2002; Persson and Tabellini 2003). Hence, electoral cycles may differ significantly between proportional and majoritarian systems or presidential and parliamentary governments. It is worth noting, though, that when we split the election dummy to account for these differences, the results (available upon request) suggest that the constitutional rules matter, but only for new democracies wherein the electoral cycle exists to begin with.

Moreover, to check whether government ideology and its effect on fiscal policy priorities (see, e.g., Hibbs, 1977; Potrafke, 2011) affects our results, we have interacted the electoral dummy variables in new and old democracies with a dummy variable that takes the value of one for left wing governments and 0 otherwise. Our results (available upon request) do not suggest that fiscal redistribution in “young democracies” is conditional on government ideology.

As already mentioned, following the approach of Brender and Drazen (2005), we consider the first four elections after a shift to a democratic regime as elections held in a new democracy. Alternatively, if we reduce this cut-off point to three elections our results remain essentially the same, whereas if we increase it to five, as expected, the effect becomes weaker.

It should be noted that we do not have enough observations to perform regressions for new democracies in developed economies.

We have to note that our measure of political instability captures social unrest events. Therefore, it may discount the potential negative attitude of ordinary citizens towards democracy, since it focuses solely on the extreme cases in which people revolt or protest owing to disappointment concerning the quality of the regime. Ideally, we would prefer to use variables from the World Value Survey that measure public perception towards democracy (see Inglehart et al. 2004). Unfortunately, for the most relevant questions of this survey (e.g., having a democratic political system), we have only three observations per country from 1994 onwards. For a more detailed discussion concerning the difficulties of measuring the “potential threat of revolution”, which is different from the “revolutionary events” that actually take place, see Aidt et al. (2014).

In additional robustness checks, we attempt to assess the importance of specific groups of countries for our results. To this end, we drop from our preferred specifications former Soviet Union countries, since the profound restructuring of those countries’ societies and economies during the period of democratization probably differs significantly from other democratizations observed in our sample. Moreover, we drop from our sample the three Sub-Saharan African countries, because we expect the accuracy of the inequality data to be thinner than in the rest of our sample. In both cases, though, our results (available upon request) remain unaffected.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2000). Why did the west extend the franchise? Democracy, inequality, and growth in historical perspective. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1167–1199.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2006). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aidt, T., & Jensen, P. (2014). Workers of the world, unite! Franchise extensions and the threat of revolution in Europe, 1820–1938. European Economic Review, 72, 52–75.

Aidt, T., & Mooney, G. (2014). Voting suffrage and the political budget cycle: evidence from the London metropolitan boroughs 1902–1937. Journal of Public Economics, 112, 53–71.

Albanesi, S. (2007). Inflation and inequality. Journal of Monetary Economics, 54(4), 1088–1114.

Alesina, A., Baqir, R., & Easterly, W. (2000). Redistributive public employment. Journal of Urban Economics, 48(2), 219–241.

Alesina, A., & Wacziarg, R. (1998). Openness, country size and government. Journal of Public Economics, 69(3), 305–321.

Amendola, A., Easaw, J., & Savoia, A. (2013). Inequality in developing economies: the role of institutional development. Public Choice, 155(1), 43–60.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Barro, R., & Lee, J. (2013). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 184–198.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groof, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: The database of political institutions. The World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176.

Besley, T., & Coate, S. (1991). Public provision of private goods and the redistribution of income. American Economic Review, 81(4), 979–984.

Block, S. (2002). Elections, electoral competitiveness, and political budget cycles in developing countries. Harvard University CID Working Paper No. 78.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2005). Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(7), 1271–1295.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2007). Why is economic policy different in new democracies? Affecting attitudes about democracy. NBER Working Paper No. 13457.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2008). How do budget deficits and economic growth affect reelection prospects? Evidence from a large panel of countries. American Economic Review, 98(5), 2203–2220.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2009). Consolidation of new democracy, mass attitudes, and clientelism. American Economic Review, 99(2), 304–309.

Bruno, G. (2005). Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Economics Letters, 87(3), 361–366.

Choi, I. (2001). Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20(2), 249–272.

Chong, A., Gradstein, M., & Calderon, C. (2009). Can foreign aid reduce income inequality and poverty? Public Choice, 140(1), 59–84.

Corvalan, A. (2014). The impact of a marginal subsidy on Gini indices. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(3), 596–603.

Drazen, A., & Eslava, M. (2010). Electoral manipulation via voter-friendly spending: theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 92(1), 39–52.

Dreher, A. (2006). Does globalization affect growth? Empirical evidence from a new index. Applied Economics, 38(10), 1091–1110.

Efthyvoulou, G. (2012). Political budget cycles in the European Union and the impact of political pressures. Public Choice, 153(3), 295–327.