Abstract

Are direct-democratic decisions more acceptable to voters than decisions arrived at through representative procedures? We conduct an experimental online vignette study with a German sample to investigate how voters’ acceptance of a political decision depends on the process through which it is reached. For a set of different issues, we investigate how acceptance varies depending on whether the decision is the result of a direct-democratic institution, a party in a representative democracy, or an expert committee. Our results show that for important issues, direct democracy generates greater acceptance; this finding holds particularly for those voters who do not agree with a collectively chosen outcome. However, if the topic is of limited importance to the voters, acceptance does not differ between the mechanisms. Our results imply that a combination of representative democracy and direct democracy, conditional on the distribution of issue importance among the electorate, may be optimal with regard to acceptance of political decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

How can individual’s preferences be mapped into political outcomes that are broadly acceptable to the constituents who must comply with collective choices? This is a longstanding question in the history of democratic thought, and two avenues have been discerned ever since: democratic decision-making through “representative” and through “direct” processes. Historically, the focus was on representative governance. Montesquieu (2005, p. 14 et seq.), for one, wrote:

The people, in whom the supreme power resides, ought to have the management of everything within their reach: what exceeds their abilities must be conducted by their ministers. […] The people are extremely well qualified for choosing those whom they are to entrust with part of their authority. […] But are they capable of conducting an intricate affair, of seizing and improving the opportunity and critical moment of action? No; this surpasses their abilities.

With the upsurge of what is perceived by many as a loss of confidence in the institutions of representative government, direct democracy increasingly has been seen as a preferable option for collective decision-making in recent decades: “Tensions have grown in most Western nations between the existing processes of representative democracy and calls by reformists for a more participatory style of democratic government” (Dalton et al. 2001, p. 141). Recent years have witnessed a “spread of direct democracy” in many democratic polities (Scarrow 2001; Matsusaka 2005; Donovan and Karp 2006). A case in point is the effort of the European Union, one of the largest democratic political systems in the world, to curtail its alleged democratic deficit (Karp et al. 2003) by introducing large-scale referendums (Auer 2005). However, the question arises whether voters see direct-democratic decisions as more acceptable than decisions achieved through representative procedures.

1.1 Why is democratic representation criticized?

For one thing, it has been shown that traditional systems of democratic representation may actually lead to a “party paradox” (Towfigh 2015). On the one hand, as Montesquieu suggests, because private individuals may not possess the time or have the incentives necessary to become well-informed regarding the full range of political problems (Downs 1957), they delegate this task to representatives—political parties and their candidates. Party labels serve as cognitive heuristics that help the electorate make meaningful decisions and choose policy positions on novel issues (Arceneaux 2008; Druckman 2001; Zaller 1992). Parties thus fulfill an indispensable intermediary function by reducing voters’ costs of information and aggregating political packages for them (Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita 2008; Jones and Hudson 1998; Müller 2000; Nisbett and Ross 1992). From this perspective, representation by political parties is functional because it facilitates specialization and the division of labor. As voters are unable to invest sufficient resources in gathering and processing political information, deciding which party offers is closest to one’s ideal point in policy space position seems more efficient. On the other hand, this system of intermediaries has also been recognized as producing severe biases in the representation of voters’ preferences, among them the opportunistic political business cycle (Nordhaus 1975; Petring 2010), corruption (Heidenheimer and Johnston 2002), other rent-seeking behavior (McCormick and Tollison 1979), and a lack of choice due to platform convergence (Bernhardt et al. 2009). These weaknesses may affect citizens’ satisfaction with the political system and lessen political participation (Scarrow 1999) or even lead to disenchantment with political parties (Klein 2005; Clarke and Stewart 1998). This paradox of representation may reduce the acceptance of political decisions by the electorate and contribute to the overall disillusion with democracy (Towfigh 2015).

1.2 Can direct-democratic procedures counter these effects?

The final verdict on the benefits of direct democracy is still out, and the literature is divided on the merits of direct-democratic procedures over conventional forms of representative democracy. Proponents argue that the former may stimulate voters’ political interest by forcing them to think about the contents of a political decision and may educate voters as political citizens (Benz and Stutzer 2004; Smith 2002). Hence, direct democracy may lead to more active participation (Schuck and de Vreese 2011; Tolbert and Smith 2005) and a better representation of voters’ preferences. The mere threat of a referendum may also discipline the representatives and induce them to align with the electorate more closely (Hajnal et al. 2002; Matsusaka and McCarty 2001). However, recent cross-country evidence on this issue offers rather sobering insights (Voigt and Blume 2015). Frequent ballots may lead to voter fatigue and thus reduce, rather than increase, electoral participation and decision quality (Bowler et al. 1992; Freitag and Stadelmann-Steffen 2010). Biases in the mapping of citizen’s preferences into political outcomes may materialize because well-organized interest groups can initiate referendums by buying the initially required number of signatures (for a discussion, see Lupia and Matsusaka 2004; Hasen 2000). In addition, ballot decisions may, under certain circumstances, suppress minorities in favor of the majority (Gerber 1996; Vatter and Danaci 2010; Hajnal et al. 2002, for a nuanced empirical study). In other words, the quality of political decisions may decline because direct-democratic procedures are prone to distortions by specific subgroups of the electorate. Moreover, only little evidence exists on how the acceptance of a political decision depends on its procedural details.

The present study investigates how acceptance differs between situations in which a political decision results from a direct-democratic mechanism, a political party, or an expert panel. Our empirical results are based on an online survey experiment conducted before the March 2011 state-level election in Rhineland-Palatinate, one of the 16 German federal states (Länder). We employed a 3 × 5 × 2 factorial design to test for differential acceptance rates of political decisions, varying the decision-making mechanism, the issue scenario, and a positive versus negative framing of the decision problem. Our results show that the acceptance of decisions does not vary per se between the decision-making mechanisms, but if voters’ core interests are at stake, they prefer more immediate control over such decisions. Therefore, we argue that political parties rightly assume their role of lowering transaction costs of voters for everyday decision-making, but they do less well in terms of acceptance of political decisions that are close to the voters’ hearts.

In the following section, we will develop our research questions based on the existing literature. Thereafter, the data collection and methodology are explained in detail before our results are presented. Finally, our paper concludes with a discussion of our results and the broader implications of our findings, suggesting avenues for future research.

2 Research question

Both direct democracy and representation through political parties seem to have functional as well as dysfunctional elements. We therefore thought it would be worthwhile to investigate the reactions of citizens to these different forms of democracy to the end of better understanding which procedures to use under which circumstances.

2.1 Is there a per-se difference between direct-democratic and representative decision-making procedures?

We started out with the assumption that the two modes of decision-making do not, per se, generate different levels of acceptance. This hypothesis is consistent with the usual assumption of outcome-based utilities typically used in rational choice models (Becker 1978). If outcomes do not differ, a voter who is driven purely by outcome-based utilities should express indifference between all investigated decision-making procedures. In the study at hand we thus test whether, controlling for personal opinion on the desired outcome of a collective choice, acceptance of outcomes of direct democracy and party representation differs materially.

2.2 What is the relationship between acceptance, decision procedure and the importance subjectively attributed to the issue?

This research question asks if we can identify factors moderating the interaction between decision procedure and decision acceptance. The conditions under which a decision is acceptable or not and its underlying procedure seem to be complex. Different explanations have been offered, and the study at hand expands on this question, too. Esaiasson et al. (2012) suggest that legitimacy is increased when individuals participate in the collective decision-making process. Based on their randomized field experiment, they conclude that “personal involvement is the main factor generating legitimacy beliefs” about distributive decisions. The finding is supported by the earlier field experiments of Olken (2010), who concludes that “direct participation in political decision making can substantially increase satisfaction and legitimacy.” Similarly, Gash and Murakami (2015) find that control over the decision increases acceptance of the decision: “individuals are more likely to agree with, and less willing to work against, policies that have been produced by their fellow citizens,” moderated by partisan affiliation.

We seek to qualify these results in a real-world election context at the level of a German federal state. More specifically, we want to investigate whether direct democracy creates higher acceptance rates in situations where the issue to be decided is important for the electorate, whereas the choice of the democratic procedure does not affect citizens’ acceptance of the decision when their stakes are in fact low. If people consider an issue of little importance, they tend to rely on partisan cues (Petty and Cacioppo 1986; Matsusaka 1992). Thus, political parties serve their function as brand names (Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita 2008) and as minimizers of voters’ information and transaction costs perfectly well in contexts of everyday decision-making. Direct-democratic procedures, in contrast, are well suited in situations where voters are intrinsically interested in obtaining more information. Two potential channels are well exemplified with rational voter models: higher stakes would increase both turnout (e.g., Palfrey and Rosenthal 1985) and collective information gathering (Martinelli 2006). For these relevant issues, citizens prefer the electorate to exercise more control, whereas moving decision making authority from voters to parties or elected representatives is an acceptable tradeoff for less important issues. These considerations lead to a preliminary second hypothesis to be tested by this study: The more important an issue is for the individual voter, the more the voter accepts it if it is made by means of direct democracy and the less the voter accepts the decision if it is made by political parties.

The policy implication of this argument is that a mix of representative democracy in “normal policy-making” contexts enhanced by direct-democratic decisions during “hot debates” is more promising than current decision-making practices in the majority of industrialized democracies—if acceptance is considered to be the ultimate benchmark for democratic aggregation of individual’s preference profiles. This, in turn, presumably can explain recent civil unrest in Western democracies after highly relevant episodes, which were largely decoupled from the individual citizen’s sphere, such as the Occupy movements, nuclear energy policy after the Fukushima meltdown, or the “Stuttgart 21” protests in Germany (for details on the cases and the alleged “new protest culture”, see Hartleb 2011).

This observation does not imply that acceptance of a decision-making mode is merely scenario-driven, but dependent on individual perceptions of importance. Citizens reject representation by intermediaries in situations they consider important; rejection of representative democracy, however, is not determined only by the overall importance of, say, the Fukushima accident or similarly prevalent issues in the media. We rather predict that differences between individuals arise because of salience even when they are presented with the same issue category, for example a nuclear energy policy decision.

3 Method and data collection

Our dataset was collected between the tenth and the 5th day before the 2011 state election in Rhineland-Palatinate, which has a population of about four million inhabitants. Seven hundred and 11 persons eligible to vote were contacted and incentivized with a fixed fee by a professional online panel provider. The questionnaire, which took about 12 min on average, was completed by 615 persons, yielding a response rate of 86.5 %. Two persons were excluded due to unreasonable age specifications of 2 and 4 years, respectively.

All analyses presented below are executed on the remaining n = 613 participants. Respondents were between 18 and 70 years old (mean = 44.3 years), and the share of female participants was 50.7 %. In terms of mean age and sex, our sample is roughly representative of the voting population of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate (see Fig. 1 for a comparison to the official population statistics). Overrepresentation of persons in the age range from 40 to 59 is evident as was underrepresentation of persons older than 60 years, which was prevalent for men as well as women (Fig. S1 in the Online Appendix).

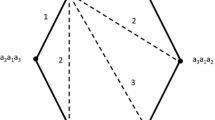

Our research design is an experimental vignette study, which allows us to study the potential influence of different decision-making institutions on the acceptance of political decisions. Each respondent faced three different political issues in random order as a within-subjects factor: nuclear energy (Scenario 1), school graduation (Scenario 2), and religious education (Scenario 3). For each participant, one out of five decision tasks was selected randomly, varying the institution that elicited the collective decision—either one of the two mass parties, “SPD” (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, the German social-democratic party) or “CDU” (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands, the German center-right party); a parliamentary majority across party lines; an expert committee; or by a direct-democratic procedure. The scenarios were presented in random order one at a time, keeping the decision-making procedure fixed. The decision-making process was held constant over the various scenarios for each participant to avoid effects owing to the salience of different institutions of collective choice. Moreover, the framing of the decision as a positive or negative outcome was determined randomly in order to cancel out potential biases caused by question wording interacting with personal opinion. Hence, the vignette study has a structure of a 3 (issue scenario) × (decision-making procedure) × 2 (positive/negative outcome) array. The first factor, the three different issue scenarios, was taken from an online voting tool called “Wahl-O-Mat” (http://www.bpb.de/node/218212, last accessed 21 April 2016).Footnote 1 This tool is run by a federal agency subordinated to the Federal Ministry of the Interior. It was set up to help voters compare their own political preferences with the official issue stances of the competing political parties and find their best match for the upcoming election. As such, it is a screening device for voters to learn about the policies the different parties advocate before an election. We adopted issue scenarios from this tool to ensure the real-world relevance of our questions.Footnote 2

Our dependent variable, acceptance of the decision, was generated as the mean response to five self-constructed questions on a scale from 1 (very little or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Participants indicated agreement with the following statements: (1) I accept the decision; (2) the decision makes me angry; (3) the decision deserves my active support; (4) the decision activates my opposition; (5) the decision makes me feel helpless (items 2, 4, and 5 with reversed scales).Footnote 3 The aggregate acceptance scale was generated for each scenario separately with high scale reliabilities in each scenario (Cronbach’s alpha for the different scenarios: nuclear α = 0.89; school α = 0.79; religion α = 0.85). Figure S3 in the Online Appendix shows the correlations between the six items used to construct the acceptance scale with a solid overall scale reliability (α = 0.85).

In addition, for each scenario we measured agreement with the contents of the decision and the importance of the topic. Agreement was assessed by letting respondents indicate whether the decision was in line with their personal opinion on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (completely) with unlabeled intervals between the endpoints. Importance of the topic was measured on a scale from 1 to 5. We further measured affective response, which was highly correlated with acceptance and brought no further insights. Participants rated their affective response to the decision by indicating on the same scale how angry, happy, nervous, and excited they felt about the decision. For reasons of simplicity, we will not report data from this measure.

4 Results

In the following, we will explore how different political decision procedures influence acceptance. Table 1 shows the summary statistics of the collected variables. At first, we will focus on the comparison between direct democracy and political parties, thereby pooling decisions made by SPD, CDU and the Parliament. The average reported acceptance for decisions resulting from direct democracy is slightly higher than decisions made by political parties (average acceptance of 3.5 vs. 3.37). Thus, we can find some evidence for direct democracy leading to greater acceptance at the aggregate level, albeit only weakly significant (p = 0.07 on a two-sided Mann–Whitney u-test). However, whether respondents perceive a decision as “acceptable” or not is influenced not only by the decision mode, but also by the respondents’ opinion on the topic and the decision. Two factors we are focusing on are the respondents’ agreement with the decision and the perceived importance of the topic.

Figure 2 reports the average acceptance depending on agreement and importance levels. It reveals that average acceptance increases with average agreement for decisions arrived at by direct democracy (Spearman’s rank correlation ρ = 0.79 with p < 0.0001) as well as with the average agreement for decision made by political parties (ρ = 0.75 with p < 0.0001). Focusing on the importance of the topics the decision was about reveals the first differences between the two decision modes. Average acceptance is not significantly correlated with the importance of the topic in the case of direct democracy (ρ = − 0.01 and p = 0.887), but significantly negatively correlated in the case of political parties (ρ = − 0.13 and p = 0.014). This correlation mostly owes to the stark drop in acceptance for important and very important topics. Comparing the average acceptance levels of only very important topics reveals them to be 27 % higher for direct democracy—a significant difference between the outcomes of the two decisions modes (p = 0.0015 on a two-sided Mann–Whitney u-test).Footnote 4

To control better for these and other additional influences on acceptance we run a series of linear random-effects models presented in Table 2 in the next subsection. Observations are clustered by respondents over three different scenarios and are based on the smaller dataset wherein direct democracy and political parties are compared with regard to their acceptance levels. In the subsequent section, we include the decisions made by expert committees. The regression models in Tables 3 and 4 replicate our previous analyses with the full dataset.

4.1 Acceptance of outcomes from direct democracy versus political parties

The dependent variable in all models is the acceptability of the decision to the respondent. Personal agreement with the outcome of the collective choice and the importance of a topic are the most important control variables. We are primarily interested in the variation in acceptance conditional on decision modes and holding personal opinion on the issue constant. In this regard, Model 1 tests whether direct-democratic decisions are significantly more acceptable than decisions made by political parties (the reference group). The Direct Democracy variable is a dummy, which is set equal to 1 if the decision mode is direct democracy and 0 otherwise (i.e., if either SPD, CDU or Parliament was the decision mode). It thus captures the effect of decisions reached by direct democracy vis-à-vis decisions made by political parties. In line with our initial assumption, direct democratic decision procedures do not generate, per se, more acceptance than decisions made by political parties. This follows from the small and insignificant main effect for Direct Democracy. As one would expect, personal opinions on the issue measured by Agreement and Importance influence the acceptability of a collective choice. The more the respondents agree with the decision, the more acceptable it is, and the more important a decision is for them, the less they accept it if they disagree with the choice.

In a next step we analyze how the acceptance of a direct-democratic decision depends on the perceived importance of the issue. In Model 2, an interaction between the variables Importance and Direct Democracy is added. The interaction term is significantly positive, while at the same time the main effect of Direct Democracy turns significantly negative. Whether direct democracy or decisions made by political parties are more acceptable depends on the importance of the issue. For the lowest importance level, acceptance of a decision made by direct democracy is 5.3 percentage points less than for a decision made by a political party (p < 0.008). As importance increases, the acceptance score goes up by roughly 4 percentage points if the decision is made through a direct-democratic procedure instead of a party. Or, conversely, any form of party involvement in the decision-making process reduces the decision’s acceptability by 4 %, for an additional point on the importance scale. Thus, for very important topics, acceptance is 6.5 % greater for decisions made by direct democracy (p = 0.012).

Model 3 demonstrates that this effect is not driven by the subject-matter of the issue at hand. Three different decision scenarios were presented to all respondents: nuclear energy (Scenario 1), school graduation (Scenario 2), and religious education (Scenario 3). While the decision in Scenario 2 generates more acceptance overall than the other two decisions, this has no impact on the size and significance of the interaction effect. In addition, we include two additional control variables in order to check for the robustness of our findings. The Influence Vote term captures the extent of perceived political self-efficacy during the upcoming state-level election: voters who tend to think that the electorate can actually change politics and policies by means of voting for representatives are more likely to accept decisions in general. However, this perceived self-efficacy does not diminish the interaction between importance of the issue and decision mode. Even if voters tend to think that their voting for parties can make a difference, they are more likely to accept direct-democratic decisions if they are important to them.

The Vote Mass Party variable indicates the intention to vote for one of the two mass parties, SPD or CDU. One may argue that supporters of these mass parties may be more supportive of decisions that are made by precisely these parties and less skeptical than other voters even when it comes to important decisions made by these parties. This is clearly not the case; again, controlling for this variable does not alter the coefficient on the interaction effect. Our finding is not conditional on mass party preferences.

Models 1, 2, and 3 impose a linear functional form on the influence of importance; however, Fig. 2 suggests that this might not be true. In Models 4 and 5 we replicate our previous results without imposing a functional form on the importance variable. In Model 4 we include interactions between Direct Democracy and each level of Importance. The coefficients show the impact on acceptance compared to a decision made by a political party for a topic with the lowest level of importance. For that importance level, a decision generated by direct democracy results in reduction of acceptability by 0.27 points, translating into a 5.9 % lower acceptance rate (albeit only weakly significant, p = 0.07). In contrast to this, direct democracy leads to a 7 % greater acceptance rate for the highest level of importance (p = 0.044, determined by comparing the coefficients Direct Democracy = 0 × Importance = 5 and Direct Democracy = 1 × Importance = 5). Again, the model confirms that acceptance declines with greater importance, as demonstrated by the significantly negative coefficients for interactions with importance levels exceeding two. Model 5 confirms the results from Model 4 after adding controls for the scenario, perceived political self-efficacy and intention to vote for one of the two mass parties.

4.2 Taking decisions by expert committees into account

While Table 2 contrasts direct democracy with political parties, Tables 3 and 4 presents additional models that contrast direct democracy with representative democracy, that is, decisions made by expert committees are added to the group of representative decision procedures, so the Direct Democracy effect is tested against decisions made by political parties or expert committees. Model 6 demonstrates that direct democracy is significantly less acceptable for issues of low importance, but more acceptable than the reference group of parties and expert committees when important issues are at stake. In other words, this is not just a difference between direct democracies and parties, but more generally a difference between direct and representative democracy. In both decision-making arrangements, parties and expert committees, decisions are one step removed from the electorate, and citizens have less control over it. While for issues with very low importance this seems not to reduce the acceptability of the outcome, it does lower it for issues considered very important.

Figure 2 visualizes these differences between direct democracy and the decision procedures based on intermediaries. While intermediaries perform better in terms of procedural acceptance for decisions of low importance to the respective voter (at importance level 1), direct democracy performs slightly better on average (level 4) and significantly better (level 5) when the issue at stake matters to the voter personally.

The remaining models provide additional checks for validity, omitted variable bias, and the functional form of the impact of importance. Model 7, for example, takes political parties out of the reference group and compares the different party configurations with the expert decision-making effect that is left in the baseline group. Separate effects are included for SPD, CDU and the majority of parties in the parliament. In Model 8 we include interaction terms with perceived issue importance for variables CDU, SPD, and Parliament, as well as controls for the scenarios, perceived political self-efficacy and intention to vote for one of the two mass parties.

Models 8 replicates Model 3 for the full dataset. It shows that the interaction effect between importance and direct democracy is not affected by the introduction of issue scenarios. As in Model 3, the positive effect of voters’ perceived self-efficacy does not change the result. Instead of Vote Mass Party, we introduce two separate control variables this time—Vote SPD and Vote CDU—as there are also separate model terms for SPD and CDU in the model specification. Neither of the control variables changes the main results presented above.

As an additional validity check, we exclude all observations for which the personal opinion of the respondent is strongly positive; that is, we exclude all observations in Model 9 where Agreement = 4 and run the analysis with the remaining observations. We would expect that those who strongly agree with the decision anyway should not have any reason to be dissatisfied with the procedure. Accordingly, the main effect should still hold for the remaining groups and not be driven by this potential artifact. And indeed, the exclusion of these observations does not alter the effect size or p value of the interaction term significantly. In other words: The observed effect results from those who disagree and are overruled and those who only “tend to” agree.

In Models 10 and 11 we again remove the functional form restriction on importance and include interactions between Direct Democracy and each level of Importance. In Model 10 we replicate Model 5 for the whole dataset; again we observe the same effects of direct democracy and importance on the acceptability of political decisions. The acceptance of decisions generally declines with increasing importance of the issue, but it does so at a considerably faster rate in systems with intermediary decision makers. As predicted, the latter seem to be more acceptable in cases where the issue is less important, while direct-democratic decisions attract significantly higher acceptance levels for important decisions. For issues of low importance, direct democracy leads to significantly lower acceptance than political representation (p = 0.042), while for important issues direct democracy leads to significantly higher level of acceptance (p = 0.016). Figure 3 visualizes the marginal effects of direct democracy for each level of importance as featured in Model 10 with all control variables included. In other words, it depicts how large the additional effect of Direct Democracy is in comparison to the other decision modes is for each level of importance. As the confidence intervals indicate, we do not see significant differences for moderate importance levels but we do see that the procedure does make for a significant difference between issues that are not considered important (1) and issues that are considered very important (5), on both ends of the scale. If an issue is considered very important, direct-democratic procedures lead to significantly higher acceptance rates.

Finally, Model 11 includes interactions between SPD, CDU, the majority of parties in Parliament and each importance level (not reported in the table). Note that the coefficients of the interactions between direct democracy and the importance levels are with respect to expert committees and the lowest importance level in this model. The effect demonstrated for the comparison between direct democracy and party decisions can be confirmed for the comparison of direct democracy and expert committees.

5 Conclusion

This paper addresses the question whether direct-democratic institutions lead to decisions that are more acceptable to voters. Our findings suggest that there is no inherent taste for any of the institutions studied. However, we find noticeable differences when we analyze the acceptance levels that different decision processes generate depending on the relevance of the issue at stake. A direct-democratic procedure produced higher acceptance for issues that are dear to voters, while institutions with intermediaries—like political parties or expert committees—seem to be slightly better equipped for low-importance, everyday decision-making situations.

This finding confirms that citizens question decisions made by parties in situations where they are intrinsically motivated to get informed, whereas the decision-making procedure does not matter in less sensitive contexts. Apparently, political parties work well in everyday policy-making contexts wherein citizens do not have enough time or incentives to acquire knowledge about current issues. In these situations, parties provide easy-to-grasp information packages, or “brands” or “labels” (Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita 2008), which reduce information costs and increase efficiency for voters. This argument may not hold when voters find a decision so important that they inform themselves on the subject—irrespective of the cost of information. They rather feel intrinsically motivated to become informed and decide for themselves. Parties as intermediaries are one step removed from the electorate, their decisions are perceived as being beyond the control of the individual voter and decoupled from the electorate at large. Voters seem to perceive direct democracy as a more acceptable procedure to reach a decision when the issue at stake is important to them individually.

Moreover, minorities may be more inclined to accept a decision if it was not made by some aloof representative, but by a broader majority of the people. This is in line with pervasive survey evidence finding that voters trust decisions arrived at by the people at large more than those made by their representatives (e.g., see Waters 2004). Our findings may also be read to support research that has found that (“hot”) pure preference issues are best decided by direct means while representative procedures are more suitable for (“cool”) matters of low importance and requiring technical expertise (Matsusaka 1992).

From the perspective of decision acceptability or procedural utility, direct-democratic procedures are significantly more efficient when issues are perceived to be important. Why should this perspective matter? The acceptance of core political institutions is a cornerstone of liberal democratic thinking (Cohen 1986; Riker 1982). A major divergence between acceptance of institutions and institutional reality might be more detrimental to the persistence of a polity than a major divergence between the actual and the desired efficacy of the same institutions. Future research may shed more light on the relation between both.

The gravity of issues might be one of the reasons for the expansion of direct-democratic institutions by several political parties in Western democracies (see Scarrow 1999). With such movements, parties can increase acceptance and mitigate political disenchantment. Research on party systems will show how political parties will cope with the challenges outlined in this article (see also the existing work of Katz and Mair 1995 and Scarrow 1999), and whether they continue to be the dominant form of political decision making as in the last two centuries.

Finally, future research should delimit the boundaries of our findings. Our study was conducted in a Western European consensual democracy at the state level using responses to an online survey. It would be interesting to explore the role of institutions like plurality versus proportional election systems or pluralist versus corporatist interest intermediation. While the degree of party divergence is similar under proportional representation and plurality rule (Ansolabehere et al. 2012), both may constrain the perceptions of procedural legitimacy in complex ways. Furthermore, the institutions may themselves be a result of underlying cultural traits and preferences for majoritarianism or consensualism (for a related finding on judicial reviews of controversial issues, see Fontana and Braman 2012).

Notes

Refer to Appendix A.2 for details on the wording of the scenarios.

Issue scenario 1 on nuclear energy generated the most public interest during the data collection phase because the Fukushima meltdown had occurred shortly beforehand. We later control for this potential bias of issue scenarios (see “Results” section below).

One assessed item (“I am shocked by the decision”) is not included in our acceptance score for conceptual reasons, although all results hold if we include it. Figure S2 in the Online Appendix shows that the main result reported in this paper holds irrespective of the use of the aggregate acceptance scale or just the first item, which inquires directly whether the respective participant “accepts” the decision. In addition, Table 4 in the Online Appendix demonstrates that our main result holds qualitatively for every single item of our acceptance score.

A similar effect can be observed if we use only the first item of the acceptance score (see Fig. S2 in the Online Appendix). Further regression analyses confirm that we can observe this effect with every single subscale of our acceptance scale (see Table 4 in Online Appendix).

References

Ansolabehere, S., Leblanc, W., & Snyder, J. M, Jr. (2012). When parties are not teams: Party positions in single-member district and proportional representation systems. Economic Theory, 49, 521–547.

Arceneaux, K. (2008). Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior, 30(2), 139–160.

Ashworth, S., & Bueno de Mesquita, E. (2008). Informative party labels with institutional and electoral variation. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 20(3), 251–273.

Auer, A. (2005). European citizens’ initiative. European Constitutional Law Review, 1(01), 79–86.

Becker, G. S. (1978). The economic approach to human behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Are voters better informed when they have a larger say in politics? Public Choice, 119, 31–59.

Bernhardt, D., Duggan, J., & Squintani, F. (2009). The case for responsible parties. American Political Science Review, 103(04), 570–587.

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., & Happ, T. (1992). Ballot propositions and information costs: Direct democracy and the fatigued voter. Western Political Quarterly, 45, 559–568.

Clarke, H. D., & Stewart, M. C. (1998). The decline of parties in the minds of citizens. Annual Review of Political Science, 1(1), 357–378.

Cohen, J. (1986). An epistemic conception of democracy. Ethics, 97(1), 26–38.

Dalton, R. J., Burklin, W., & Drummond, A. (2001). Public opinion and direct democracy. Journal of Democracy, 12(4), 141–153.

Donovan, T., & Karp, J. A. (2006). Popular support for direct democracy. Party Politics, 12(5), 671–688.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Druckman, J. N. (2001). Using credible advice to overcome framing effects. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 17, 62–82.

Esaiasson, P., Gilljam, M., & Persson, M. (2012). Which decision-making arrangements generate the strongest legitimacy beliefs? evidence from a randomised field experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 51(6), 785–808.

Fontana, D., & Braman, D. (2012). Judicial backlash or just backlash? Evidence from a national experiment. Columbia Law Review, 112(4), 731–799.

Freitag, M., & Stadelmann-Steffen, I. (2010). Stumbling block or stepping stone? The influence of direct democracy on individual participation in parliamentary elections. Electoral Studies, 29(3), 472–483.

Gash, A., & Murakami, M. H. (2015). Venue effects: How state policy source influences policy support. Politics & Policy, 43(5), 679–722.

Gerber, E. R. (1996). Legislative response to the threat of popular initiatives. American Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 99–128.

Hajnal, Z. L., Gerber, E. R., & Louch, H. (2002). Minorities and direct legislation: Evidence from California ballot proposition elections. Journal of Politics, 64(1), 154–177.

Hartleb, F. (2011). A new protest culture in Western Europe? European View, 10, 3–10.

Hasen, R. L. (2000). Parties take the initiative (and vice versa). Columbia Law Review, 100(3), 731–752.

Heidenheimer, A. J., & Johnston, M. (Eds.). (2002). Political corruption. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Jones, P., & Hudson, J. (1998). The role of political parties: An analysis based on transaction costs. Public Choice, 94(1–2), 175–189.

Karp, J. A., Banducci, S. A., & Bowler, S. (2003). To know it is to love it? Satisfaction with democracy in the European Union. Comparative Political Studies, 36(3), 271–292.

Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy: The emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics, 1(1), 5–28.

Klein, M. (2005). Die Entwicklung der Beteiligungsbereitschaft bei Bundestagswahlen. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 57(3), 494–522.

Lupia, A., & Matsusaka, J. G. (2004). Direct democracy: New approaches to old questions. Annual Review of Political Science, 7, 463–482.

Martinelli, C. (2006). Would rational voters acquire costly information? Journal of Economic Theory, 129(1), 225–251.

Matsusaka, J. G. (1992). Economics of direct legislation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 541–571.

Matsusaka, J. G. (2005). Direct democracy works. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(2), 185–206.

Matsusaka, J. G., & McCarty, N. M. (2001). Political resource allocation: Benefits and costs of voter initiatives. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 17(2), 413–448.

McCormick, R. E., & Tollison, R. D. (1979). Rent-seeking competition in political parties. Public Choice, 34(1), 5–14.

Montesquieu (1748/2005). The spirit of laws. Livonia: Lonang Institute.

Müller, W. C. (2000). Political parties in parliamentary democracies: Making delegation and accountability work. European Journal of Political Research, 37(3), 309–333.

Nisbett, R. E., & Ross, L. (1992). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Nordhaus, W. D. (1975). The political business cycle. Review of Economic Studies, 42(2), 169–190.

Olken, B. A. (2010). Direct democracy and local public goods: Evidence from a field experiment in Indonesia. American Political Science Review, 104(2), 243–267.

Palfrey, T. R., & Rosenthal, H. (1985). Voter participation and strategic uncertainty. American Political Science Review, 79(1), 62–78.

Petring, A. (2010). Welfare state reforms and the political business cycle. Journal for Institutional Comparisons, 8(2), 47–52.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 124–205.

Riker, W. H. (1982). Liberalism against populism: A confrontation between the Theory of Democracy and the Theory of Social Choice. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Scarrow, S. E. (1999). Parties and the expansion of direct democracy. Party Politics, 5(3), 341–362.

Scarrow, S. E. (2001). Direct democracy and institutional change. Comparative Political Studies, 34(6), 651–665.

Schuck, A. R. T., & de Vreese, C. H. (2011). Public support for referendums: The role of the media. West European Politics, 34(2), 181–207.

Smith, M. A. (2002). Ballot initiatives and the democratic citizen. Journal of Politics, 64(03), 892–903.

Tolbert, C. J., & Smith, D. A. (2005). The educative effects of ballot initiatives on voter turnout. American Politics Research, 33(2), 283–309.

Towfigh, E. V. (2015). Das Parteien-Paradox. Ein Beitrag zur Bestimmung des Verhältnisses von Demokratie und Parteien. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Vatter, A., & Danaci, D. (2010). Mehrheitstyrannei durch Volksentscheide? Zum Spannungsverhältnis zwischen direkter Demokratie und Minderheitenschutz. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 51, 205–222.

Voigt, S., & Blume, L. (2015). Does direct democracy make for better citizens? A cautionary warning based on cross-country evidence. Constitutional Political Economy, 26, 391–420.

Waters, M. D. (Ed.). (2004). Direct Democracy in Europe: A comprehensive reference guide to the initiative and referendum process. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society (Max Planck Digital Library). We are grateful to Steve Ansolabehere, Paul Bauer, Rebekka Herberg, Becky Morton, Isabelle Stadelmann-Steffen, the participants of seminars at NYU and the Workshop on Political Parties (Bonn) as well as two anonymous referees and the two editors, William F. Shughart II and Peter T. Leeson, for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Towfigh, E.V., Goerg, S.J., Glöckner, A. et al. Do direct-democratic procedures lead to higher acceptance than political representation? . Public Choice 167, 47–65 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0330-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0330-y