Abstract

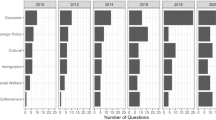

This paper assesses the influence of the electoral threat of third parties on major-party roll call voting in the US House. Although low-dimensionality of voting is a feature of strong two-party politics, which describes the contemporary era, there is significant variation across members. I hypothesize that major-party incumbents in districts under a high threat from third-party House candidates cast votes that do not fit neatly onto the dominant ideological dimension. This hypothesis is driven by (1) third party interests in orthogonal issues, and (2) incumbents accounting for those interests when casting votes in order to minimize the impact of third parties. An empirical test using data from the 105th to 109th Congresses provides evidence of this effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As in previous works on the subject, the term third party is used interchangeably with minor party, independent, and non-major party.

See Appendix A, which also substantiates this claim using measures that I introduce later in the empirical section. All appendices are available at http://www.msu.edu/~leedan/.

Cases might exist in which a major-party candidate would prefer a third candidate to compete in the election if that third candidate is believed to be a spoiler candidate. For instance, during the 2006 US Senate campaign, Rick Santorum and his supporters aided attempts to get the Green Party candidate onto the general election ballot in order to steal votes from the Democratic nominee, Bob Casey, Jr. In an analysis of all House members, however, such asymmetries likely balance out and are not too widespread. More importantly, although Santorum might have preferred a Green candidate in that election, he still needed to be concerned with the possible entry of a different third-party candidate (say a Libertarian) who would steal votes from him.

I did consider the possibility that third-party threat may influence a member’s roll call voting ideology (NOMINATE score). Following the logic of Palfrey (1984) and Lee (2012a), a member might be more extreme when representing a district that is likely to have third-party competitors. One problem with testing this hypothesis is that these formal models consider major-party candidate divergence, but those data do not include the location of major-party challengers to the officeholder. With that caveat, simply testing the effect of threat on incumbent extremism on both the first and second dimensions does not show any effect (results available upon request). This may be due to the absence of a control for challenger ideology, but it could also be the case that third-party threat does not systematically influence roll call voting in this way.

See Appendix A for additional discussion on the validity of using this measure of model fit to capture third-party dimensionality. To stress that third-party threat influences dimensionality rather than simply ambiguity (variance of voting), I tested the effect of threat on an alternative voting measure as the dependent variable: bootstrapped standard errors of members’ NOMINATE scores, which is provided in the NOMINATE data set. Omitted regression results do not suggest any relationship. As a last point on the choice of the dependent variable, although the percentage of votes misclassified has a nice intuitive interpretation, Appendix B uses the geometric mean probability (GMP) as the dependent variable to account for some potential shortcomings of the misclassification measure. The results are substantively the same.

As Poole and Rosenthal (2007) do, lopsided votes (minority vote is less than 2.5 %) are excluded.

The summary statics for % Misclassified are minimum 0, maximum 39.9, mean 10.4, and standard deviation 5.1.

This two-step model does not suffer from endogeneity between the third-party threat and vote dimensionality. One might claim that if members vote high dimensionally in the face of third-party threat to limit their influence, then misclassified votes might influence the threat negatively—in which case, threat would be correlated with the errors in Eq. (2). Any bias, however, likely works against finding the effect posited by the threat hypothesis. More crucially, the variables of interest are expectations. Furthermore, since ballot access signature requirements are an exogenous cost that strongly influences third-party entry and votes, it provides additional leverage for estimating a threat’s seriousness (following the logic of two-stage least squares, which is closely related to the two-step model used here). Lastly, see Appendix C for further discussion of the influence of major-party incumbent roll call voting on third-party electoral success.

Because some lagged variables are used to measure the district propensity for a third-party candidate, I need to account for redistricting in the probit model of entry. Rather than exclude all districts where there was some minimal level of redistricting, only non-continuous districts are excluded (Carson et al. 2007). Non-continuous districts are defined as districts where over one-half of the population changes after a redistricting. Including continuing districts is appropriate, since that district before and after redistricting is roughly comparable.

Ballot access laws are taken from Markin (1995a, 1995b) and updated to incorporate changes since 1996. Depending on the state, there may be different requirements for minor parties (to “form” and get ballot access) and for independent (nonaffiliated) candidates. The minimum of the two possible requirements is used in the analysis, since it captures the cost of the path of least resistance (also see Burden 2007; Lee 2012b).

The heterogeneity index is based on housing, income, race, age, and education (Sullivan 1973). Since this measure is based on Census data, it is constant for a district within a Census-decade. Ensley et al. (2009) develop a measure of district complexity (inverse of correlation of voter preferences between economic and cultural dimensions) that one might conjecture measures potential third-party support. However, what benefits third parties is finding voters supportive of their policy stances, rather than district complexity per se. Omitted results substantiate this argument.

I use the total vote share of all third-party and independent candidates in a district. Results do not change if the average candidate vote share or vote share of the most successful candidate is used. Substantive results do not change if more comprehensive models are estimated, such as including a measure of competitiveness to capture Duvergerian incentives for voters, which depress third-party vote shares in close elections.

Notice that I conjecture that the requirement has a negative impact on the “third-party vote share in a district,” rather than on the “vote share of an actual third-party candidate.” Lee (2012b) shows that there is an important distinction between the two. Using the Tobit specification to estimate (net, ex ante) expected vote shares is most suitable for measuring threat. Estimating an OLS model instead does not change the substantive results.

These measures indeed appear to capture a district characteristic that is relatively constant over the time period analyzed. Pairwise correlations of the measure within a district between two adjacent years ranges between 0.6017 and 0.7231.

Note that extremism on the second dimension is not connected to third-party threat. As stated in an earlier footnote, I considered this possibility, but the correlation between the threat measures and ideological extremism on either dimension is weak.

Substantive results do not change if the absolute value difference from the national Democratic presidential vote is used instead.

Substantive results do not change with the inclusion of additional variables. Seniority, which counts the number of terms held by the member as of that Congress (freshmen are coded as one), was included in alternative models as a robustness check (Brady and Rohde 2009). Seniority and total terms served are highly correlated (over 0.9), and the results do not change with the inclusion of both or just one of the variables. Yoshinaka and Grose (2011) and Brady and Rohde (2009) also suggest including the vote share of the member in the most recent election, but unreported results revealed no effect. Lastly, I tested for the possibility that the effect of third-party threat is conditional on the competitiveness/marginality of the incumbent’s seat. Including a dummy for marginality (won with less than 60 % of the vote) and its interaction with the threat variable does not change the substantive results. Neither the dummy nor interaction is statistically significant, and the coefficient for third-party threat does not change.

Louisiana and Vermont are dropped from the analysis—the former because of its unique primary and general electoral system and the latter because it representative was third-party US House member Bernie Sanders.

References

Abramson, P. R., Aldrich, J. H., Paolino, P., & Rohde, D. W. (1992). Sophisticated voting in the 1988 presidential primaries. The American Political Science Review, 86(1), 55–69.

Bailey, M. A. (2007). Comparable preference estimates across time and institutions for the Court, Congress, and Presidency. American Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 433–448.

Bertelli, A. M., & Grose, C. R. (2011). The lengthened shadow of another institution? Ideal point estimates for the Executive Branch and Congress. American Journal of Political Science, 55(4), 767–781.

Brady, M. C., & Lee, D. J. (2012). Party effects and predictability of voting in the US House. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, New Orleans, LA.

Brady, M. C., & Rohde, D. W. (2007). When good predictions go bad: vote context, win margins, and misclassified votes in the 75th to 108th congresses. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, IL.

Brady, M. C., & Rohde, D. W. (2009). Moving beyond mavericks: an exploration of competing conceptions of individual member vote misclassifications in the 80th to 110th congresses. Presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Political Science Association, New Orleans, LA.

Burden, B. C. (2007). Ballot regulations and multiparty politics in the states. PS, Political Science & Politics, 40, 669–673.

Burnham, W. D. (1970). Critical elections and the mainsprings of American politics. New York: Norton.

Carson, J. L., Crespin, M. H., Finocchiaro, C. J., & Rohde, D. W. (2007). Redistricting and party polarization in the US House of Representatives. American Politics Research, 35(6), 878–904.

Clinton, J. D., Jackman, S., & Rivers, D. (2004). The statistical analysis of roll call data. The American Political Science Review, 98(2), 355–370.

Cox, G. W. (1994). Strategic voting equilibria under the single nontransferable vote. The American Political Science Review, 88(3), 608–621.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. D. (1993). Legislative leviathan: party government in the House. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Drometer, M., & Rincke, J. (2009). The impact of ballot access restrictions on electoral competition: evidence from a natural experiment. Public Choice, 138, 461–474.

Duverger, M. (1963). Political parties: their organization and activity in the modern state. New York: Wiley. North, B. and North, R., tr.

Ensley, M. J., Tofias, M. W., & de Marchi, S. (2009). District complexity as an advantage in congressional elections. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 990–1005.

Fenno, R. F. (1978). Home style: House members in their districts. Boston: Little, Brown.

Fiorina, M. P. (1974). Representatives, roll calls, and constituencies. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Fleck, R. K., & Kilby, C. (2002). Reassessing the role of constituency in congressional voting. Public Choice, 112, 31–53.

Greenberg, J., & Shepsle, K. (1987). The effect of electoral rewards in multiparty competition with entry. The American Political Science Review, 81(1), 525–538.

Heckman, J. J., & Snyder, J. M. (1997). Linear probability models of the demand for attributes with an empirical application to estimating the preferences of legislators. The Rand Journal of Economics, 28(0), 142–189.

Herron, M., & Lewis, J. (2007). Did Ralph Nader spoil a Gore presidency? A ballot-level study of Green and Reform Party voters in the 2000 presidential election. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 2(3), 205–226.

Hirano, S. (2008). Third parties, elections, and roll-call votes: The Populist Party and the late nineteenth-century US Congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 33(1), 131–156.

Holian, D. B., Krebs, T. B., & Walsh, M. H. (1997). Constituency opinion, Ross Perot, and roll-call behavior in the US House: the case of the NAFTA. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 22(3), 369–392.

Jacobson, G. C. (1989). Strategic politicians and the dynamics of US House elections, 1946–86. The American Political Science Review, 83(3), 773–793.

Jenkins, J. A. (1999). Examining the bonding effects of party: a comparative analysis of roll-call voting in the US and Confederate Houses. American Journal of Political Science, 43(4), 1144–1165.

Lacy, D., & Burden, B. (1999). The vote-stealing and turnout effects of Ross Perot in the 1992 US presidential election. American Journal of Political Science, 43(1), 233–255.

Lauderdale, B. E. (2010). Unpredictable voters in ideal point estimation. Political Analysis, 18(2), 151–171.

Lee, D. J. (2012a). Anticipating entry: effects of third party entry on major party positioning. Political Research Quarterly, 65(1), 138–150.

Lee, D. J. (2012b). Take the good with the bad: cross-cutting effects of ballot access requirements on third party electoral success. American Politics Research, 40(2), 267–292.

Lem, S. B., & Dowling, C. M. (2006). Picking their spots: minor party candidates in gubernatorial elections. Political Research Quarterly, 59(3), 471–480.

Markin, K. M. (1995a). Ballot access 2: for congressional candidates. Washington: Federal Election Commission.

Markin, K. M. (1995b). Ballot access 4: for political parties. Washington: Federal Election Commission.

Martin, A. D., & Quinn, K. M. (2002). Dynamic ideal point estimation via Markov chain Monte Carlo for the US Supreme Court, 1953–1999. Political Analysis 10(2), 134–153.

Miller, G., & Schofield, N. (2003). Activists and partisan realignment in the United States. The American Political Science Review, 97(2), 245–260.

Murphy, K. M., & Topel, R. H. (1985). Estimation and inference in two-step econometric models. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 3(4), 370–379.

Palfrey, T. (1984). Spatial equilibrium with entry. Review of Economic Studies, 51(1), 139–156.

Palfrey, T. (1989). A mathematical proof of Duverger’s Law. In P. Ordeshook (Ed.), Models of strategic choice in politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2007). Ideology & Congress. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Rapoport, R., & Stone, W. (2001). It’s Perot, stupid! The legacy of the 1992 Perot movement in the major-party system, 1992–2000. PS, Political Science & Politics, 34(1), 49–58.

Rapoport, R. B., & Stone, W. J. (2005). Three’s a crowd: the dynamic of third parties, Ross Perot, and Republican resurgence. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Richman, J. (2008). Uncertainty and the prevalence of committee outliers. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 33(2), 323–347.

Rohde, D. W. (1991). Parties and leaders in the postreform House. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rosenstone, S., Behr, R., & Lazarus, E. (1996). Third parties in America: citizen response to major party failure (2nd ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sullivan, J. L. (1973). Political correlates of social, economic, and religious diversity in the American states. The Journal of Politics, 35(1), 70–84.

Sundquist, J. L. (1983). Dynamics of the party system. Washington: The Brookings Institution.

Yoshinaka, A., & Grose, C. R. (2011). Ideological hedging in uncertain times: inconsistent legislative representation and voter enfranchisement. British Journal of Political Science, 41(4), 765–794.

Acknowledgements

An early version was presented at the 2009 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. The author thanks Jean-François Godbout, Brendan Nyhan, Matt Grossmann, Ani Sarkissian, Sarah Reckow, Thomas Hammond, and anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions. The author is responsible for all remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D.J. Third-party threat and the dimensionality of major-party roll call voting. Public Choice 159, 515–531 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0066-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0066-x