Abstract

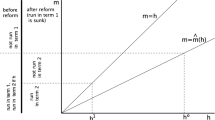

It is well established that geographic areas benefit, in terms of the share of government spending they capture, from having a legislator with longer tenure, holding constant the tenure of other legislators. However, the implications of this literature for how the total production of legislation changes if all members gained seniority is less clear. Increased levels and dispersion of seniority within Congress generate a cartel-like effect, whereby legislators restrict the quantity of legislation enacted and increase the average price of each passed bill. The analysis provides a natural experiment to gauge the impacts of the emergence of the congressional committee system.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Crain, W. M. (1977). On the structure and stability of political markets. Journal of Political Economy, 85, 829–842.

Crain, W. M. (1979). Cost and output in the legislative firm. The Journal of Legal Studies, 8, 607–621.

Crain, W. M., & Tollison, R. D. (1980). The sizes of majorities. Southern Economic Journal, 46, 726–734.

Denzau, A. T., & Munger, M. C. (1986). Legislators and interest groups: how unorganized interests get represented. The American Political Science Review, 80, 89–106.

Gini, C. (1912). Variabilita’e mutabilita’ studi economicogiuridici universita’ di’ cagliari. III, 2a, Bologna.

Holcombe, R. G. (1999). Veterans interests and the transition to government growth: 1870–1915. Public Choice, 99, 311–326.

Holcombe, R. G., & Parker, G. R. (1991). Committees in legislatures: a property rights perspective. Public Choice, 70, 11–20.

Leibowitz, A., & Tollison, R. D. (1980). A theory of legislative organization: making the most of your majority. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 94, 261–77.

Levitt, S. D., & Poterba, J. M. (1999). Congressional distributive politics and state economic performance. Public Choice, 99, 185–216.

Lorenz, M. (1905). Methods of measuring the concentration of wealth. Publications of ASA, 70, 209–219.

Luce, R. (1935). Legislative problems: development, status, and trend of the treatment and exercise of lawmaking powers. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

McCormick, R. E., & Tollison, R. D. (1978). Legislatures as unions. Journal of Political Economy, 86, 63–78.

McCormick, R. E., & Tollison, R. D. (1981). Politics, legislation, and the economy: an inquiry into the interest-group theory of government. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff.

Moore, S., & Steelman, A. (1994). Term limits: an antidote to federal red ink? Briefing Paper #21. Cato Institute.

Nordhaus, W. D. (1975). The political business cycle. Review of Economic Studies, 42, 169–190.

Parker, G. R. (1992). The distribution of honoraria income in the U.S. Congress: who gets rents in legislatures and why? Public Choice, 73, 167–181.

Payne, J. L. (1990). The Congressional brainwashing machine. Public Interest, 100, 3–15.

Payne, J. L. (1991). The culture of spending: why Congress lives beyond our means. San Francisco: ICS Press.

Romer, T., & Rosenthal, H. (1978). Political resource allocation, controlled agendas, and the status quo. Public Choice, 33, 27–43.

Ryan, M.E. (2008). Legislative tenure, federal spending, and state economic performance: 1981–2004. Mimeo.

Ryan, M. E. (2009). The evolution of legislative tenure in the United States Congress: 1789–2004. Mimeo.

Shughart, W. F., & Tollison, R. D. (1985). Legislation and political business cycles. Kyklos, 38, 43–59.

Shughart, W. F., & Tollison, R. D. (1986). On the growth of government and the political economy of legislation. In Richard O. Zerbe Jr. (Ed.), Research in law and economics (pp. 111–127). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Stigler, G. J. (1976). The sizes of legislatures. The Journal of Legal Studies, 5, 17–34.

Weingast, B. R., & Marshall, W. J. (1988). The industrial organization of Congress; or, why legislatures, like firms, are not organized as markets. Journal of Political Economy, 96, 132–163.

Weingast, B. R., Shepsle, K. A., & Johnsen, C. (1981). The political economy of benefits and costs: a neoclassical approach to distributive politics. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 642–664.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sobel, R.S., Ryan, M.E. Seniority and anti-competitive restrictions on the legislative common pool: tenure’s impact on the overall production of legislation and the concentration of political benefits. Public Choice 153, 171–190 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9780-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9780-4