Abstract

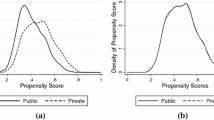

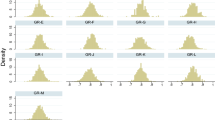

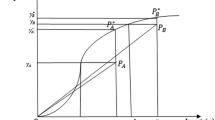

The programme for international student assessment (PISA) 2006 Report (OECD, PISA 2006: science competencies for tomorrow’s world, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris in 2007) showed significant differences among Spanish students attending publicly financed schools. Publicly financed schools include entirely public schools and schools that are privately managed but publicly funded. Families with a lower socioeconomic status may self-select into public schools, so a direct efficiency comparison between the two school types could lead to flawed conclusions because of the possible school selection bias. In this paper, we suggest using a propensity score matching approach in order to correctly analyze the impact of school ownership on student performance. After tackling the self-selection problem, we use a stochastic parametric distance function framework to compare student efficiency and productivity in both school types across ten Spanish regions using PISA 2006 data. Furthermore, we propose two original measures to analyze the impact of school ownership on academic performance across regions: the average treatment effect on the treated on the production frontier and the average treatment effect on the treated assuming school inefficiency. We find that, on average, private government-dependent schools are more productive than public schools, although efficiency results across regions are highly divergent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The organizations are mostly Catholic schools, teachers’ cooperatives, non-for-profit organizations or simply private enterprises.

There are also private government-independent schools, controlled by non-government organizations, which receive most of their core funding from student fees. In this paper, we focus only on the publicly financed schools.

An article from EL MUNDO reports that PGDS are on average 69 % more expensive than the public schools. In 87 % of PGDS, it is compulsory for students to wear school uniforms, and services, such as school bus and lunch, are 30 % more expensive than in PS. Moreover, 91 % of PGDS ask for a fee to parents to improve school facilities or to offer some extra-curricular activities while this fee does not exist in PS. http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2012/09/12/espana/1347457645.html (the article is only available in Spanish).

Another possible approach would be to combine stochastic frontier analysis and switching regression (Greene 2010).

Because this analysis is performed at the student level, we refer, throughout this paper, to the efficiency scores obtained by a frontier analysis at student level as technical or educational efficiency and the mean efficiency obtained by a group of students attending the same school type as school inefficiency.

The Cobb Douglas form does not satisfy the concave imposition in the output dimension.

Distance function parameters must satisfy some restrictions like symmetry and homogeneity of degree +1 for outputs, which implies that the distance of the decision-making unit to the boundary of the production set is measured by radial expansions.

A student attending a PS is a counterfactual of a student from a PGDS if both students have similar personal and family characteristics and have a very similar a priori probability of attending PGDS.

Gertler et al. (2011, pp. 109) define the PSM method as follows: “The propensity score matching method tries to mimic the randomized assignment to treatment and comparison groups by choosing for the comparison group those units that have similar propensities to the units in the treatment group. Since propensity score matching is not a real randomized assignment method, but tries to imitate one, it belongs to the category of quasi-experimental methods”.

A relevant assumption for the PSM approach is that possible unobservable variables of students affecting both school ownership choice and results should have the same distribution for the treated and non-treated groups (Imbens 2004). We do think that this is the case for the Spanish educational context.

This method consists of an algorithm that matches the probability of each student attending a PGDS with the PS counterfactual that has the nearest probability (propensity score). There are alternative approaches to the nearest neighbor estimator for obtaining the matches, although the analysis of these alternatives is beyond the scope of this paper. For more information on this topic, see Heckman et al. (1997).

Unconfoundedness also called conditional independence assumption (CIA) implies the independence of \( Y(0),Y(1)\, \)and S conditional on Z.

For an extensive review of this issue, see Caliendo and Kopeing (2008)

We assume that technologies are different and so management drivers differ in the two school types: whereas PGDS teachers are hired and fired by school principals and are managed more flexibly, PS teachers need to pass a very hard state exam and cannot be fired. Our argument is confirmed later in Table 9 where input parameters are generally significantly different for PGDS and PS estimations.

Some divergences in the student results may also be explained by the regional context due to factors like local economic development, employment possibilities, immigrant population, rural area extensions, socioeconomic background of the population or differences among their educational policies.

Note that only school choice variables were considered for the ATT measurement, while school inputs and technology may differ between school types in the real educational production process.

To do this, we perform a radial projection of all students to the estimated production frontier (Eq. 4) assuming also that expected random noise is equal to zero.

Thus, our methodology can provide a wide range of ATTpf and ATTasi measurements according to different student typologies.

As a consequence of the use balancing and common support properties applied to ensure that only students with the same probability of attending PGDS are matched, the total sample size shrinks from 15,918 to 15,123 students.

PSM is generally calculated using Pared, Immigrant and City as control variables, with the exception of Basque Country and Castile-Leon where the balancing property is tested using Hisei is used instead of Pared.

Parental education (Pared) is classified using ISCED (OECD, 2000). Parental education indexes are constructed by recoding educational qualifications into the following categories: (0) None; (1) ISCED 1 (primary education); (2) ISCED 2 (lower secondary); (3) ISCED Level 3B or 3C (vocational/pre-vocational upper secondary); (4) ISCED 3A (upper secondary) and/or ISCED 4 (non-tertiary post-secondary); (5) ISCED 5B (vocational tertiary); and (6) ISCED 5A, 6 (theoretically oriented tertiary and postgraduate).

Hisei is the highest occupational level of either parent according to the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI). For more details, see Ganzeboom et al. (1992).

According to official Spanish educational statistics captured by MEC (2008), foreign students in non-university education have grown from a total number of 72,335 in 1998 to 695,190 in 2008.

Population size is less than 3,000 for a village, hamlet or rural area; 3,000 to about 15,000 for a small town; 15,000 to about 100,000 for a town; 100,000 to about 1,000,000 for a city and 1,000,000 or over for a large city.

A condition is that all input variables must be continuous and show significant positive correlations within each school type and across all the regions. The remaining control variables are categorical variables (dummies) or do not have a clear significant positive correlation with output (schsize) in our database.

Since the original variable has positive and negative values, we have re-scaled all the values to assure that all the input variables have positive values.

More than 40% of Spanish students had been retained at least once in 2006 (source: PISA 2006 database).

From now on and for presentation purposes we only report the mean results of analyzing the five plausible values in each discipline.

In PS from Cantabria performance is also better for reading and science, but these differences were found not to be statistically significant.

One hundred distance functions were estimated (five estimations by two school types by ten regions), although, for simplicity’s sake, these tables are not published in this paper. They are all available upon request from the authors.

Notice that the sign of the first-order input parameters may be changed in order to provide a straightforward analysis of output-input elasticities.

This produces three predicted values (mathematics, reading and science), one for each distance function estimation.

References

Afonso A, St Aubyn M (2006) Cross-country efficiency of secondary education provision: a semi-parametric analysis with non-discretionary inputs. Econ Model 23(3):476–491

Alchian AA (1950) Uncertainty, evolution and economic theory. J Polit Econ 58:211–221

Alexander K, Entwistle D, Dauber S (2003) On the success of failure. Cambridge University Press, New York

Banker RD, Janakiraman S, Natarajan R (2004) Analysis of trends in technical and allocative efficiency: an application to Texas public school districts. Eur J Oper Res 154:477–491

Barnett R, Glass J, Snowdon R, Stringer K (2002) Size, performance and effectiveness: cost-constrained measures of best-practice performance and secondary school size. Educ Econ 10(3):291–311

Betts JR, Shkolnik JL (2000) The effects of ability grouping on student achievement and resource allocation in secondary schools. Econ Educ Rev 19:1–15

Bradley S, Taylor J (1998) The effect of school size on exam performance in secondary schools. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 60:291–324

Calero J, Escardibul JO (2007) Evaluación de servicios educativos: el rendimiento en los centros públicos y privados medido en PISA-2003. Hacienda Pública Española 183(4):33–66

Calero J, Choi A, Waisgrais S (2009) Determinantes del rendimiento educativo del alumnado de origen nacional e inmigrante. Cuadernos Económicos del ICE 78:281–311

Caliendo M, Kopeing S (2008) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv 22(1):31–72

Card D, Krueger A (1992) Does school quality matter? Returns to education and the characteristics of public schools in the United States. J Polit Econ 100:1–40

Carroll J (1963) A model of schooling learning. Teach Coll Rec 64:723–733

CD OE (1999) Classifying educational programmes. Manual for ISCED-97 implementation in OECD countries. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Chiswick B, DebBurman N (2004) Educational attainment: analysis by immigrant generation. Econ Educ Rev 23(4):361–379

Chubb JE, Moe TM (1990) Politics, markets and America’s schools. The Brookings Institution, Washington

Coelli T, Perelman S (1999) A comparison of parametric and non-parametric distance functions, with application to European railways. Eur J Oper Res 117:326–339

Coelli T, Perelman S (2000) Technical efficiency of European railways, a distance function approach. Appl Econ 32:1967–1976

Contreras D (2002) Vouchers, school choice and the access to higher education. Economic Growth Center. Yale University. Center Discussion Paper N°845

Cordero JM, Crespo E, Santín D (2010) Factors affecting educational attainment: evidence from Spanish PISA 2006 Results. Reg Sect Econ Stud 10(2):55–76

Cordero JM, Crespo E, Pedraja F, Santín D (2011) Exploring educational efficiency divergences across Spanish regions in PISA 2006. Revista de Economia Aplicada 57:117–145

Cortes KE (2006) The effects of age at arrival and enclave schools on the academic performance of immigrant children. Econ Educ Rev 25:121–132

Dronkers J, Robert P (2008) Differences in scholastic achievement of public, private government-dependent and private independent schools. A cross-national analysis. Educ Policy 22(4):541–577

EC M (2008) Estadísticas de las enseñanzas no universitarias. Datos Avance. Curso 2007–2008. Ministerio de Educación, Madrid

Entorf H, Minoiu N (2005) What a difference immigration policy makes: a comparison of PISA scores in Europe and traditional countries of immigration. Ger Econ Rev 6(3):355–376

Friedman M, Friedman R (1981) Free to choose. Avon, New York

Fuentes A (2009) Raising education outcomes in Spain. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 666

Gang IN, Zimmermann KF (2000) Is child like parent? Educational attainment and ethnic origin. J Hum Res 35:550–569

Ganzeboom H, De Graaf P, Treiman J, De Leeuw J (1992) A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Soc Sci Res 21(1):1–56

Gertler P, Patrinos HA, Rubio-Codina M (2007) Impact evaluation for school-based management reform (designing impact evaluation no. 10.) Washington, World Bank

Gertler PJ, Martinez S, Premand P, Rawlings LB and Vermeersch CMJ (2011) Impact evaluation in practice. The World Bank. Washington. http://www.worldbank.org/ieinpractice

Greene W (2010) A stochastic frontier model with correction for sample selection. J Prod Anal 34(1):15–24

Grosskopf S, Hayes K, Taylor L, Weber W (1997) Budget-constrained frontier measures of fiscal equality and efficiency in schooling. Rev Econ Stat 79(1):116–124

Hanushek EA (1979) Conceptual and empirical issues in the estimation of educational production functions. J Hum Res 14:351–388

Hanushek EA (1986) The Economics of schooling: production and efficiency in public schools. J Econ Lit 24:1141–1177

Hanushek EA (1997) Assessing the effects of schools resources on students performance: an up-date. Educ Eval Policy Anal 19:141–164

Hanushek EA (2003) The failure of input based schooling policies. Econ J 113:64–98

Hanushek EA, Luque J (2003) Efficiency and equity in schools around the world. Econ Educ Rev 22:481–502

Hanushek EA, Kain JF, Markman JM, Rivkin SG (2001) Does peer ability affect student achievement. Working Paper 8502, National Bureau of Economic Research

Heckman J, Navarro-Lozano S (2004) Using matching, instrumental variables, and control function to estimate economic choice models. Rev Econ Stat 86:30–57

Heckman J, Ichimura H, Todd PE (1997) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Rev Econ Stud 64(4):605–654

Holmes C, Matthews K (1984) The effects of non-promotion on elementary and junior high school pupils: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 54:225–236

Hoxby CM (2000) The effects of class size on student achievement: new evidence from population variation. Quart J Econ 115:1239–1285

Hoxby CM (ed) (2003) The economics of school choice. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Imbens GW (2004) Nonparametric estimation of average treatment effects under exogeneity: a review. Rev Econ Stat 86:4–29

Kingdon G (1996) The quality and efficiency of private and public education: a case study of urban India. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 58(1):57–82

Krueger AB (1999) Measuring labor’s share. Am Econ Rev 89(2):45–51

Krueger AB (2003) Economics considerations and class size. Econ J 113:34–63

Levin HM (1974) Measuring efficiency in educational production. Public Finance Quart 2:3–24

Lewis L, Patrinos HA (2012) Impact evaluation of private sector participation in education. CfBT Education Trust, The World Bank

Lovell CAK, Richardson S, Travers P, Wood LL (1994) Resources and functionings, a new view of inequality in Australia. In: Eichhorn W (ed) Models and Measurement of Welfare and Inequality. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 787–807

Mancebón MJ, Calero J, Choi A, Ximenez D (2012) Efficiency of public and publicly-subsidized high schools in Spain. Evidence from PISA 2006. J Oper Res Soc 63:1516–1533

Mayen CD, Balagtas JV, Alexander CE (2010) Technology adoption technical efficiency: organic and conventional dairy farms in United States. Am J Agric Econ 92(1):181–195

McCarty T, Yaisawarng S (1993) Technical efficiency in New Jersey school districts. In: Fried H, Lovell CAK, Schmidt S (eds) The measurement of productive efficiency: techniques and applications. Oxford University Press, New York

McEwan PJ (2001) The effectiveness of public catholic and non-religious private schools in Chile’s voucher system. Educ Econ 9(2):103–128

Mislevy RJ, Beaton AE, Kaplan B, Sheehan KM (1992) Estimating population characteristics from sparse matrix samples of item responses. J Educ Meas 29:133–161

Mora T, Escardibul JO, Espasa M (2010) The effects of regional educational policies on school failure in Spain. Revista de Economía Aplicada 54(18):79–106

Muñiz M (2002) Separating managerial inefficiency and external conditions in data. Eur J Oper Res 143(3):625–643

Nechyba TJ (2000) Mobility targeting and private-school vouchers. Am Econ Rev 90(1):130–146

Newhouse D, Beegle K (2006) The effect of school type on academic achievement. J Hum Res 41(3):529–557

OECD (2007) PISA 2006: science competencies for tomorrow’s world, vol 1. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

OECD (2009) PISA data analysis manual. SPSS users, 2nd edn. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Perelman S, Santín D (2011) Measuring educational efficiency at student level with parametric stochastic distance functions: an application to Spanish PISA results. Educ Econ 19(1):29–49

Pierson LH, Connell JP (1992) Effect of grade retention on self-system processes, school engagement, and academic performance. J Educ Psychol 84:300–307

Roederick M, Jacob B, Bryk A (2002) The impact of high-stakes testing in Chicago on student achievement in promotional gate grades. Educ Eval Policy Anal 24:333–357

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55

Salinas J, Santín D (2012) Selección escolar y efectos de la inmigración sobre los resultados académicos españoles en PISA 2006. Revista de Educación 358:382–405

Sander W (2001) The effect of Catholic schools on religiosity, education and competition. National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education. Occasional Paper 32

Schnepf VS (2008) Inequality of learning amongst immigrant children in industrialized countries. IZA Discussion Paper 3337

Shepard L, Smith M, Marion S (1996) Failed evidence on grade retention. Psychol Sch 33:251–261

Vandenbergue V, Robin S (2004) Evaluating the effectiveness of private education across countries: a comparison of methods. Lab Econ 11(4):487–506

Witte JF (1998) The Milwaukee voucher experiment. Educ Eval Policy Anal 20(4):229–251

Woessman L (2001) Why students in some countries do better. Educ Matters 1(2):67–74

Zinovyeva N, Felgueroso F, Vázquez P (2008) Immigration and students’ achievement in Spain. Working Paper 2008–2007, Fundación de Estudios de Economía

Acknowledgments

This paper owes a debt to Joaquín Artés and Sergio Perelman for their valuable comments and encouragement. We also thank Boris Bravo-Ureta, Astrid Cullmann, Antonio Estache and two anonymous referees for helpful discussions and suggestions. The authors received financial support from the Spanish Government, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Projects ECO-2009-13864-C03-01 and ECO-2009-13864-C03-02 and research grants from the Junta de Extremadura (research group SEJ015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crespo-Cebada, E., Pedraja-Chaparro, F. & Santín, D. Does school ownership matter? An unbiased efficiency comparison for regions of Spain. J Prod Anal 41, 153–172 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-013-0338-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-013-0338-y