Abstract

Manufacturing produces both good and “bad” outputs, such as waste, which have negative environmental effects. Economic (e.g., tax) and non-economic (e.g., reputation) incentives encourage firms to reduce waste. However, such practices are costly because decreases in output produced or increases in inputs used may accompany waste reduction. We employ a cost function approach to evaluate patterns of output and waste production and capital, labor, and materials use, for UK manufacturing plants. We find that costs of waste reduction generally imply increasing materials use and capital and labor input saving, but vary by county, region, and industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the Department of Environment the largest proportion of waste sent to landfill originates from the demolition and construction industry. Source: National Waste Production Survey, 1998/1999.

See http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/subjects/waste/ for more details.

ISO 14001 is an environmental management system (EMS) introduced in 1996 by the International Standards Organization. Firms are audited and accredited by independent accreditation agencies. Part of ISO 14001 is the process of firms setting their own environmental targets, however these targets are completely voluntary; they are not externally enforced or sanctioned.

There are over 100 active waste minimization clubs across England & Wales, providing advice to well over 5000 companies. The focus of these groups varies: some provide support to industries across a range of business sectors, while others support specific sector groups. Their aim is to encourage reductions in resource use and waste emissions, and is supported by the environment agency.

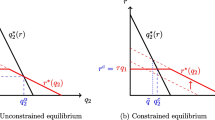

In econometric modeling of bad outputs, as opposed to DEA, it makes no difference if the bad is treated as an input or an output; all that changes is the sign associated with the bad. In our model waste is treated as a bad quantity. It is not optimized over and doesn′t appear as part of costs, which are costs for the inputs that are optimized over. On the other hand, if we chose to include waste as an input, it would not be optimized over, and would become fixed in the cost function.

County level here refers to traditional counties, metropolitan and unitary authorities.

These characteristics indicators were chosen for their significant cost-impacts and explanatory power for county-level cost variations in preliminary analysis. Population density and ISO 14001 accreditations were also tried, but either had insignificant effects or exacerbated rather than attenuated the variability across counties.

The question concerning waste was included for the first time in 1999. At time of writing this paper, the ARD data set was only available until the end of 2001.

These are listed as “metropolitan” areas in government statistics, and have city councils as opposed to county councils.

Note that for qualitative or “counter” variables, like dummy variables and the t time trend, such an elasticity would be log-linear instead of log–log; e.g., \(\varepsilon_{{\rm SV}_{\rm B},{D}_{s}}=\partial\ln \hbox{SV}_{\rm B}/\partial D_{\rm s}\), and \(\varepsilon_{{\rm SV}_{\rm B},{t}}=\partial \ln\hbox{SV}_{\rm B}/\partial{t}.\)

The estimation of a capital-quasi-fixed or variable (restricted) cost function was also estimated. However, perhaps because the panel data represents a relatively short time span, the results estimated were very similar to those for the total cost function.

County level dummy variables (fixed effects) were also incorporated in preliminary empirical investigation, but contributed to instability of the parameter estimates and thus volatility of the elasticity estimates without substantively affecting the overall or county-type patterns, and so were omitted from our final model.

By construction the cost function is homogeneous of degree one in input prices, so the input demand equations are homogeneous of degree zero.

As discussed in Paul and MacDonald (2003), the choice of instruments is typically arbitrary and can generate volatility in the estimates that are exacerbated in a system of equations. There also can be issues when an autoregressive structure is explicitly incorporated, especially when lags of the exogenous variables are used (although for our model we dropped the autoregressive adjustment).

The parameters on the industry dummy variables are not included in the table due to confidentiality restrictions.

These materials composition impacts are not well represented by our data.

The elasticities for SIC16, Tobacco products, are not reported due to confidentiality restrictions.

Recall that “heaviness” is defined as the proportion of heavy to overall manufacturing, and “density as manufacturing to other employment.

References

Arora S, Cason T (1996) Why do firms volunteer to exceed environmental regulations? understanding participation in EPA’s 33/50 program. Land Econ 72(4):413–432

Arora S, Cason T (1999) Do community characteristics influence environmental outcomes? Evidence from the toxics release inventory. Southern Econ J 65(4):691–716

Chapple W, Morrison Paul CJ, Harris R (2005) Manufacturing and corporate environmental responsibility: cost implications of voluntary waste minimisation. Struct Change Econ Dyn 16:347–373

Chung Y, Fare R, Grosskopf S (1997) Productivity and undesirable outputs: a directional distance function approach. J Environ Manage 51:229–240

Cohen JP, Morrison CJ, Paul (2005) Agglomeration economies and industry location decisions: the impacts of spatial and industrial spillovers. Reg Sci Urban Econ 35(3):215–237

Färe R, Grosskopf S, Lovell K, Pasurka C (1989) Multilateral productivity comparisons when some outputs are undesirable: a non parametric approach. Rev Econ Stat 71:90–98

Färe R, Grosskopf S, Lovell K, Yaisawarang S (1993) Derivation of shadow prices for undesirable outputs: a distance function approach. Rev Econ Stat 75(2):374–380

Gallant A, Holly A (1980) Statistical inference in an implicit, non linear, simultaneous equation model in the context of maximum likelihood estimation. Econometrica 48: 697–720

Gallant A, Jorgenson D (1979) Statistical Inference for a System of Simultaneous, Non Linear, Implicit Equations in the Context of Instrumental Variable Estimation. J Econom 11:275–302

Harris RID, Drinkwater S (2000) UK plant and machinery capital stocks and plant closures. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 62:239–261

Harris RID (2002) Foreign ownership and productivity in the united kingdom – some issues when using ARD establishment level data. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 49(3):318–335

Harris RID, Robinson C (2002) The impact of foreign acquisitions on total factor productivity: plant-level evidence from UK manufacturing, 1987–1992. Rev Econ Stat 84:562–568

McWilliams A, Siegel D (2001) Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad Manage Rev 26(1):117–127

Oulton N (1997) The ABI respondents database: a new resource for industrial economics research. Econ Trends 528:46–57

Paul CJM (2001) Market and cost structure in the US beef packing industry: a plant-level analysis. Am J Agric Econ 83(1):64–76

Paul CJM, MacDonald JR (2003) Tracing the effects of agricultural commodity prices and food costs. Am J Agric Econ 85(3):633–646

Paul CJM, Siegel DS (1999) Scale economies and industry agglomeration externalities: a dynamic cost function approach. Am Econ Rev 89(1):272–290

Reinhard S, Lovell K, Thijssen G (2000) Environmentally detrimental variables: estimated with SFA and DEA. Eur J Operat Res 121:287–303

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chapple, W., Harris, R. & Paul, C.J.M. The cost implications of waste reduction: factor demand, competitiveness and policy implications. J Prod Anal 26, 245–258 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-006-0014-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-006-0014-6