Abstract

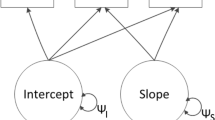

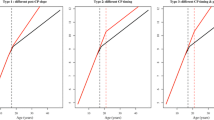

Growth mixture models (GMMs) are applied to intervention studies with repeated measures to explore heterogeneity in the intervention effect. However, traditional GMMs are known to be difficult to estimate, especially at sample sizes common in single-center interventions. Common strategies to coerce GMMs to converge involve post hoc adjustments to the model, particularly constraining covariance parameters to equality across classes. Methodological studies have shown that although convergence is improved with post hoc adjustments, they embed additional tenuous assumptions into the model that can adversely impact key aspects of the model such as number of classes extracted and the estimated growth trajectories in each class. To facilitate convergence without post hoc adjustments, this paper reviews the recent literature on covariance pattern mixture models, which approach GMMs from a marginal modeling tradition rather than the random effect modeling tradition used by traditional GMMs. We discuss how the marginal modeling tradition can avoid complexities in estimation encountered by GMMs that feature random effects, and we use data from a lifestyle intervention for increasing insulin sensitivity (a risk factor for type 2 diabetes) among 90 Latino adolescents with obesity to demonstrate our point. Specifically, GMMs featuring random effects—even with post hoc adjustments—fail to converge due to estimation errors, whereas covariance pattern mixture models following the marginal model tradition encounter no issues with estimation while maintaining the ability to answer all the research questions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Technically, all people are in all classes simultaneously but their contribution to the likelihood of each class is weighted by the probability that they belong to each class. We simplify the description in the text to keep the conceptual idea succinct.

All Mplus input and output files used in the analysis are available from https://osf.io/sjer5/

Based on reviewer comments, we also explore latent basis and multivariate pattern cluster mixtures models to consider robustness of class assignment and trajectories to a quadratic growth function. The results from this exploration revealed that repeated measure means were very reasonably approximated by a quadratic function and that class assignment was not appreciably different among different latent class methods. Full details of this robustness analysis are provided in the appendix.

The number of parameters required for unstructured covariance matrices can be unruly when the number of repeated measures exceeds about 5 (McNeish & Harring, 2020, p. 953). There were no issues in this data containing only 4 unequally spaced repeated measures, so we opted for the most general structure to avoid any potential issues associated with covariance misspecification (e.g., Heggeseth & Jewell, 2013). Readers considering CPGMMs with data featuring more repeated measures are encouraged to consider more parsimonious covariance structures such as Toeplitz, first-order autoregressive, Markov, or first-order factor analytic. More detail on selecting between competing covariance structures in CPGMMs is provided in the appendix.

This interpretation presumes that classes are substantively meaningful entities, typically deemed a direct application of mixture models. It is also possible that the classes are merely a mathematical device to approximate a complex reality that may simply be non-normal (Bauer & Curran, 2003), often deemed an indirect application of mixture models. There is currently no reliable method by which to distinguish direct and indirect applications (Bauer & Curran, 2004). This applies equally to random effect GMMs and CPGMMs.

References

Bauer, D. J., & Curran, P. J. (2003). Distributional assumptions of growth mixture models: Implications for overextraction of latent trajectory classes. Psychological Methods, 8, 338–363.

Bauer, D. J., & Curran, P. J. (2004). The integration of continuous and discrete latent variable models: Potential problems and promising opportunities. Psychological Methods, 9, 3–29.

Biernacki, C. (2005). Testing for a global maximum of the likelihood. Journal of Computational & Graphical Statistics, 14, 657–674.

Biernacki, C., & Govaert, G. (1997). Using the classification likelihood to choose the number of clusters. Computing Science and Statistics, 29, 451–457.

Burton, P., Gurrin, L., & Sly, P. (1998). Extending the simple linear regression model to account for correlated responses: An introduction to generalized estimating equations and multi-level mixed modelling. Statistics in Medicine, 17, 1261–1291.

Cook, D. I., Gebski, V. J., & Keech, A. C. (2004). Subgroup analysis in clinical trials. Medical Journal of Australia, 180, 289.

Cook, R. D., & Weisberg, S. (1982). Residuals and influence in regression. Chapman.

Curran, P. J., Obeidat, K., & Losardo, D. (2010). Twelve frequently asked questions about growth curve modeling. Journal of Cognition and Development, 11, 121–136.

Dayton, C. M., & Macready, G. B. (1988). Concomitant-variable latent-class models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 173–178.

Diallo, T. M., Morin, A. J., & Lu, H. (2016). Impact of misspecifications of the latent variance covariance and residual matrices on the class enumeration accuracy of growth mixture models. Structural Equation Modeling, 23, 507–531.

Diallo, T. M., Morin, A. J., & Parker, P. D. (2014). Statistical power of latent growth curve models to detect quadratic growth. Behavior Research Methods, 46, 357–371.

Diggle, P., Heagerty, P., Liang, K. Y., & Zeger, S. (2002). Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford University Press.

Draper, D. (1995). Assessment and propagation of model uncertainty. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 57(1), 45–70.

Firth, J., Torous, J., Nicholas, J., Carney, R., Pratap, A., Rosenbaum, S., & Sarris, J. (2017). The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry, 16, 287–298.

Gardiner, J. C., Luo, Z., & Roman, L. A. (2009). Fixed effects, random effects and GEE: What are the differences? Statistics in Medicine, 28, 221–239.

Gilthorpe, M., Dahly, D., Tu, Y., Kubzansky, L., & Goodman, E. (2014). Challenges in modeling the random structure correctly in growth mixture models and the impact this has on model mixtures. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 5, 197–205.

Goodman, L. A. (1974). Exploratory latent structure analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika, 61, 215–231.

Hanley, J. A., Negassa, A., Edwardes, M. D. D., & Forrester, J. E. (2003). Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: An orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 364–375.

Hannan, E. J., & Quinn, B. G. (1979). The determination of the order of an autoregression. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 41, 190–195.

Harring, J. R., & Hodis, F. A. (2016). Mixture modeling: Applications in educational psychology. Educational Psychologist, 51, 354–367.

Haymond, M. W. (2003). Measuring insulin resistance: A task worth doing. But how? Pediatric Diabetes, 4, 115–118.

Heagerty, P. J., & Zeger, S. L. (2000). Marginalized multilevel models and likelihood inference. Statistical Science, 15, 1–26.

Hedeker, D., & Gibbons, R. D. (2006). Longitudinal data analysis. Wiley.

Heggeseth, B. C., & Jewell, N. P. (2013). The impact of covariance misspecification in multivariate Gaussian mixtures on estimation and inference: An application to longitudinal modeling. Statistics in Medicine, 32, 2790–2803.

Henderson, N. C., & Rathouz, P. J. (2018). AR (1) latent class models for longitudinal count data. Statistics in Medicine, 37, 4441–4456.

Henson, J. M., Reise, S. P., & Kim, K. H. (2007). Detecting mixtures from structural model differences using latent variable mixture modeling: A comparison of relative model fit statistics. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 202–226.

Hipp, J. R., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychological methods, 11, 36–53.

Hubbard, A. E., Ahern, J., Fleischer, N. L., Van der Laan, M., Satariano, S. A., Jewell, N., Bruckner, T. & Satariano, W. A. (2010). To GEE or not to GEE: comparing population average and mixed models for estimating the associations between neighborhood risk factors and health. Epidemiology, 21, 467-474.

Huang, F. L. (2016). Alternatives to multilevel modeling for the analysis of clustered data. The Journal of Experimental Education, 84, 175–196.

Hurvich, C. M., & Tsai, C. L. (1989). Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika, 76(2), 297–307.

Imai, K., & Ratkovic, M. (2013). Estimating treatment effect heterogeneity in randomized program evaluation. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 7, 443–470.

Infurna, F. J., & Grimm, K. J. (2018). The use of growth mixture modeling for studying resilience to major life stressors in adulthood and old age: Lessons for class size and identification and model selection. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73, 148–159.

Infurna, F. J., & Jayawickreme, E. (2019). Fixing the growth illusion: New directions for research in resilience and posttraumatic growth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28, 152–158.

Infurna, F. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2016). Resilience to major life stressors is not as common as thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 175–194.

Jedidi, K., Jagpal, H. S., & DeSarbo, W. S. (1997). Finite-mixture structural equation models for response-based segmentation and unobserved heterogeneity. Marketing Science, 16, 39–59.

Jennrich, R. I., & Schluchter, M. D. (1986). Unbalanced repeated-measures models with structured covariance matrices. Biometrics, 42, 805–820.

Jo, B., Findling, R. L., Wang, C. P., Hastie, T. J., Youngstrom, E. A., Arnold, L. E., ... & Horwitz, S. M. (2017). Targeted use of growth mixture modeling: A learning perspective. Statistics in Medicine, 36, 671–686.

Jo, B., Wang, C. P., & Ialongo, N. S. (2009). Using latent outcome trajectory classes in causal inference. Statistics and Its Interface, 2, 403–412.

Jung, T., & Wickrama, K. A. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 302–317.

Kim, S.-Y. (2012). Sample size requirements in single- and multiphase growth mixture models: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 19, 457–476.

Kooken, J., McCoach, D. B., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2019). The impact and interpretation of modeling residual noninvariance in growth mixture models. The Journal of Experimental Education, 87, 214–237.

Kreuter, F., & Muthén, B. (2008). Analyzing criminal trajectory profiles: Bridging multilevel and group-based approaches using growth mixture modeling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 24, 1–31.

Laird, N. M., & Ware, J. H. (1982). Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics, 38, 963–974.

Lanza, S. T., & Cooper, B. R. (2016). Latent class analysis for developmental research. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 59–64.

Matsuda, M., & DeFronzo, R. A. (1999). Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: Comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care, 22, 1462–1470.

McLachlan, G. J., & Peel, D. (2004). Finite mixture models. Wiley.

McNeish, D., & Harring, J. R. (2021). Improving convergence in growth mixture models without covariance structure constraints. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280220981747

McNeish, D. Harring, J. R., & Bauer, D. J. (2021). Nonconvergence, covariance constraints, and class enumeration in growth mixture models. PsyArXiv

McNeish, D., & Harring, J. R. (2020). Covariance pattern mixture models: Eliminating random effects to improve convergence and performance. Behavior Research Methods, 52, 947–979.

McNeish, D., Stapleton, L. M., & Silverman, R. D. (2017). On the unnecessary ubiquity of hierarchical linear modeling. Psychological Methods, 22, 114–140.

Muthén, B., Brown, C. H., Masyn, K., Jo, B., Khoo, S. T., Yang, C. C., ... & Liao, J. (2002). General growth mixture modeling for randomized preventive interventions. Biostatistics, 3, 459–475.

Muthén, B., & Shedden, K. (1999). Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics, 55, 463–469.

Nagin, D. S. (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods, 4, 139–157.

Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2005). Developmental trajectory groups: Fact or a useful statistical fiction?. Criminology, 43, 873-904.

Northouse, L. L., Katapodi, M. C., Song, L., Zhang, L., & Mood, D. W. (2010). Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta‐analysis of randomized trials. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 60, 317–339.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535-569.

Peña, A., McNeish, D., Ayers, S. L., Olson, M. L. V., Wyst, K. B., Williams, A. N., & Shaibi, G. Q. (2020). Response heterogeneity to lifestyle intervention among Latino adolescents. Pediatric Diabetes, 21, 1430–1436.

Petras, H., & Masyn, K. (2010). General growth mixture analysis with antecedents and consequences of change. In A. R. Piquero & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative criminology (pp. 69–100). Springer.

Pocock, S. J., Assmann, S. E., Enos, L. E., & Kasten, L. E. (2002). Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: Current practice and problems. Statistics in Medicine, 21, 2917–2930.

Ryder, J. R., Kaizer, A. M., Jenkins, T. M., Kelly, A. S., Inge, T. H., & Shaibi, G. Q. (2019). Heterogeneity in response to treatment of adolescents with severe obesity: The need for precision obesity medicine. Obesity, 27, 288–294.

Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52, 333–343.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464.

Sijbrandij, J. J., Hoekstra, T., Almansa, J., Reijneveld, S. A., & Bültmann, U. (2019). Identification of developmental trajectory classes: Comparing three latent class methods using simulated and real data. Advances in Life Course Research, 42, 100288.

Soltero, E. G., Konopken, Y. P., Olson, M. L., Keller, C. S., Castro, F. G., Williams, A. N., ... & Pimentel, J. (2017). Preventing diabetes in obese Latino youth with prediabetes: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 17, 261.

Tabák, A. G., Jokela, M., Akbaraly, T. N., Brunner, E. J., Kivimäki, M., & Witte, D. R. (2009). Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: An analysis from the Whitehall II study. The Lancet, 373, 2215–2221.

Tofighi, D. & Enders, C. K. (2007). Identifying the correct number of classes in a growth mixture models. In G.R. Hancock, G.R. & K.M. Samuelson (Eds.), Advances in latent variable mixture models (p. 317–341). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

van De Schoot, R., Sijbrandij, M., Winter, S. D., Depaoli, S., & Vermunt, J. K. (2017). The GRoLTS-checklist: Guidelines for reporting on latent trajectory studies. Structural Equation Modeling, 24, 451–467.

Verbeke, G., & Lesaffre, E. (1996). A linear mixed-effects model with heterogeneity in the random-effects population. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91, 217–221.

Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18, 450–469.

Wickrama, K. K., Lee, T. K., O’Neal, C. W., & Lorenz, F. O. (2016). Higher-order growth curves and mixture modeling with Mplus: A practical guide. Routledge.

Williams, A. N., Konopken, Y. P., Keller, C. S., Castro, F. G., Arcoleo, K. J., Barraza, E., ... & Shaibi, G. Q. (2017). Culturally-grounded diabetes prevention program for obese Latino youth: Rationale, design, and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 54, 68–76.

Winkley, K., Landau, S., Eisler, I., & Ismail, K. (2006). Psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 333, 65.

Zeger, S. L., Liang, K. Y., & Albert, P. S. (1988). Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics, 44, 1049–1060.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20MD002316 and U54MD002316), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK107579 and 3R01DK107579-03S1), and the Institute of Educational Sciences (R305D190011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Arizona State University (ASU) Institutional Review Board and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to Participate

All participants and a parent or guardian provided informed consent and assent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McNeish, D., Peña, A., Vander Wyst, K.B. et al. Facilitating Growth Mixture Model Convergence in Preventive Interventions. Prev Sci 24, 505–516 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01262-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01262-3