Abstract

Understanding people’s travel behavior is necessary for achieving goals such as increased bicycling and walking, decreased traffic congestion, and adoption of clean-fuel vehicles. To understand underlying motivations, researchers increasingly are adding subjective variables to models of travel behavior. This article presents a systematic review of 158 such studies. Nearly every reviewed article finds subjective variables to be predictive of transport outcomes. However, the 158 reviewed studies include 2864 distinct subjective survey questions. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to reach definitive conclusions about which subjective variables are most important for which transport outcomes. In addition to heterogeneity, challenges of this literature also include an unclear direction of causality and tautological relationships between some subjective variables and behavior. Within the constraints imposed by these challenges, we attempt to evaluate the explanatory power of subjective variables, which subjective variables matter most for which transport choices, and whether the answers to these questions vary between continents. To reduce heterogeneity in future studies, we introduce the Standardized Transport Attitude Measurement Protocol, which identifies a curated set of subjective questions. We have also developed an open-access database of the reviewed studies, including all subjective survey questions and models, with an interactive, searchable interface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Travel behavior models are used in transportation planning and policymaking to inform decisions including infrastructure spending, land use planning, air quality mitigation planning, and business site selection. Understanding how people make travel behavior choices is necessary for achieving goals such as decreased traffic congestion, adoption of clean-fuel vehicles, and public health improvement through increased bicycling and walking. To understand underlying motivations, researchers increasingly are adding attitudes to the sociodemographics and built environment factors typically used to explain travel behavior.

In a strict psychological sense, attitudes refer to a positive or negative evaluation of a particular object or behavior (Maio et al. 2019, ch.1). In the transport literature, however, attitudes are defined more broadly, and can include true attitudes as well as other constructs such as preferences (Kim et al. 2017; Namgung and Jun 2019), perceptions (Haustein and Jensen 2018; Park and Akar 2019), habits (Atasoy et al. 2013; Namgung and Akar 2015), values (Mokhtarian and Salomon 1997; Xia et al. 2017), beliefs (De Vos et al. 2018; Adnan et al. 2019), perceived social norms (Popuri et al. 2011; Van Acker et al. 2014), perceived behavioral control (Van Acker et al. 2011; Olde Kalter et al. 2020) and lifestyles (Aditjandra et al. 2013; Circella et al. 2017). We adopt this broad view and use “attitudes” as a shorthand for any subjective measure used in travel demand modeling.

There is a large academic literature that incorporates attitudes into models of travel behavior, but no comprehensive review exists to help applied modelers understand how and when attitudes improve predictive power. This article fills that gap. We systematically review this body of literature and identify generalizable findings that can be used by researchers and practitioners wishing to make use of attitudes in their travel behavior models.

We searched the Scopus research database to identify papers for inclusion in this review. We required that “attitudes”, “beliefs”, or “perceptions” as well as “mode choice”, “location choice”, “vehicle ownership”, or “vehicle type choice” were mentioned in the title, abstract, or keywords. We additionally required that “factor analysis”, “principal component analysis”, “structural equation”, “hybrid choice”, “integrated choice”, or “latent class” appeared in any field of the article’s metadata. The full query appears in Appendix B. We also included a small number of papers that were referenced by the found papers, or that the authors were aware of personally.

Hundreds of candidate articles were identified. The following additional criteria were required for inclusion in this review:

-

1.

The sample size must be 300 or greater.

-

2.

The analysis must include a multivariate model with a transport or residential location choice-related dependent variable, and at least two sociodemographic control variables. While qualitative research into the relationships between attitudes and transport choices is valuable and often forms the basis for later quantitative research, it is not included in this review.

-

3.

The analysis must include either factor analysis or principal component analysis to capture latent attitudes (see Sect. 2). Structural equations and hybrid/integrated choice models are included because a factor analysis is integrated into both of these approaches.

-

4.

The article must not be primarily focused on long distance travel, evacuation travel, autonomous vehicles, or children’s travel. These are sufficiently different from general travel behavior that the attitude—travel behavior relationship may differ.

The final 158 studies selected for review span the time period from 1981 to 2020. Early foundational papers in this literature were published in the 1990s (e.g., Kitamura et al. 1997), with growth in the literature throughout the 2000s. 130 of the 158 papers in this review were published during the decade between 2010 and 2019.

All of the attitudinal statements, factors, and models in the reviewed articles were entered into a standardized database to allow for easy comparisons between models and to allow researchers to locate prior survey questions and model results. This database is available through an interactive interface at https://files.indicatrix.org/attitudes/.

The next section provides an overview of techniques used in the literature for measuring attitudes. We then discusses key challenges, including both theoretical obstacles and study design challenges. After this, we present main findings, examining whether attitudes are predictive overall and for specific transport choices, as well as geographic variation in the literature. Lastly, we make methodological recommendations for future research and conclude with a research agenda.

Appendix A presents the Standardized Transport Attitudes Measurement Protocol (STAMP), a tool that we developed in conjunction with this review to facilitate standardization of attitudinal measurement in this literature.

Measuring attitudes

The objective of attitude measurement is to obtain a robust metric that captures a person’s viewpoint on concepts such as the importance of environmental protection or the convenience of using transit. Standard practice is to ask people’s level of agreement with a series of indicator statements such as those in Fig. 1. These statements are then combined into attitudinal factors using factor analysis or the related technique of principal components analysis.

Attitudinal statements contributing to the “Pro-Environment” latent attitudinal factor (Kitamura et al. 1997)

Attitudinal statements differ from attitudinal factors. Agreement or disagreement with each attitudinal statement is caused by an underlying latent attitudinal factor, which is not directly measured (Van Bork et al. 2017). For instance, an underlying “Pro-Environment” attitude might cause a respondent to agree with “stricter vehicle smog control laws should be introduced and enforced” and disagree with “environmental protection costs too much.”

Factors are the preferred method of including attitudinal variables in models of choice, for two reasons. First, factors are the theoretical drivers of choice. Second, attitudinal factors are unlikely to be affected by idiosyncratic responses to individual questions.

Fundamental challenges in the attitude-travel literature

A key finding of our literature review is that there are fundamental challenges that plague interpretation of the relationship between attitudes and travel behavior. The attitudinal statements used rarely overlap between studies, some included attitudes are nearly synonymous with the behaviors they explain, and the direction of causality between attitudes and behavior is unclear.

Heterogeneity in attitude measurement

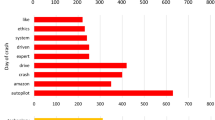

There is remarkable heterogeneity along three key dimensions of attitudinal measurement in this literature. First, attitudinal constructs are not consistent across studies of particular transport choices. Second, studies use different sets of attitudinal statements to represent seemingly similar attitudinal constructs. Third, there is substantial wording variation even among attitudinal statements that are almost certainly meant to capture the same information. In the 158 papers we reviewed for this study, we identified 2864 distinct attitudinal statements. This heterogeneity makes drawing general conclusions about the relationship between attitudes and travel behavior difficult.

Table 1 demonstrates these concerns. The top rows show two different papers predicting the same outcome with different factors. The middle rows show strikingly different questions associated with a “pro-environment” factor in two different papers, while the bottom rows show how questions about personal identity and public transport can be worded differently.

To promote reproducibility and comparability going forward, we have developed STAMP, a comprehensive instrument for measuring transport-relevant attitudes, which is presented in Appendix A. STAMP draws heavily on previously used questions from the literature and provides a recommended list of attitudinal statements that measure many common transport-related attitudes. Given the breadth of these attitudes, there are 100 questions in this protocol. We do not expect all researchers to use all questions, but rather to choose the questions most relevant to their topics of inquiry.

Unclear direction of causality

There are multiple theoretical constructs that guide the use of attitudinal variables in social science research. By far the most prominent attitude-behavior theory is Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (1991). This construct supposes that choices are influenced by attitudes, defined as positive or negative inclinations toward a certain behavior. However, attitudes are identified as only one of the constructs which determine behavior. The other components of the Theory of Planned Behavior are perceived behavioral control and social norms (both of which might themselves be considered attitudes under the less stringent definition used in travel behavior research). When perceived behavioral control or social norms are a major constraint—say, for expensive international travel or socially undesirable behaviors such as driving under the influence, the importance of one’s attitude may diminish. In short, the Theory of Planned Behavior always assumes a causal impact in the direction of attitudes on behavior, but the strength of this relationship may vary.

The competing Theory of Cognitive Dissonance is at times in conflict with Theory of Planned Behavior, postulating that attitudes may in fact be adjusted to be consistent with behavior (Festinger 1962). That is, behavior has a causal impact on attitudes rather than the relationship of the opposite direction proposed by Ajzen. The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance does not reject the causal relationship pointing from attitudes to behavior, but simply provides the reverse as a second plausible pathway for addressing behavior and attitudes which are at odds with each other. Further theories addressing the causal impact of behavior on attitudes have also emerged in recent years (van Wee et al. 2019; De Vos et al. 2021).

Other theories about the attitude-behavior relationship can be found less prominently in the literature. Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action is a forerunner to the Theory of Planned Behavior and posits a similar relationship of attitudes influencing behavior (Fishbein 1979). Triandis’ theory on values, attitudes, and interpersonal behavior also suggests that attitudes influence behavior, but introduces additional variables such as habits and perceived consequences of an action (Triandis 1979).

Most studies in this literature rely on the Theory of Planned Behavior either implicitly or explicitly for theoretical justification and treat attitudes as independent variables. However, if attitudes are affected by behavior as postulated by the Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, using attitudes as independent variables presents an endogeneity problem. When there is a causal link from the dependent to independent variables, coefficient estimates are biased (Cameron and Trivedi 2005, p. 92). Endogeneity problems also make it difficult to understand the effects of attitude changes on travel behavior (Chorus and Kroesen 2014; Kroesen and Chorus 2018).

An increasing number of studies note the potential for a bidirectional relationship (Wang and Chen 2012; de Abreu e Silva 2014; Lin et al. 2017; Moody and Zhao 2019; Barajas 2019), with some studies explicitly finding that behaviors influence attitudes more strongly than attitudes influence behaviors (Kroesen et al. 2017; van de Coevering et al. 2021). The direction of causality likely depends on the attitude. For example, an attitude such as “It is inconvenient to commute without a car”Footnote 1 is likely influenced by past commuting experience; the influence of behavior on attitude may be dominant here. However, other attitudes may be more likely to influence travel behavior than to be influenced by travel behavior. For instance, “I am concerned about global warming” may influence travel behavior, but be less influenced by past travel experiences. Many attitudes included in this literature probably have a bidirectional relationship with behavior.

Most research on how attitudes affect travel behavior use cross-sectional data. Cross-sectional studies show correlations, but longitudinal studies are the best way to examine causal relationships (Chorus and Kroesen 2014). While this is a challenge with many variables used in travel behavior models, it is especially salient with research on attitudes due to the lack of a clear theoretical argument for one direction of causality over the other (Kroesen and Chorus 2018). Future research on attitudes should use longitudinal samples whenever possible.

Self-evident attitudinal relationships

Many studies include explicit preferences about the transport choice being modelled among the attitudinal constructs used to predict that transport choice. For instance, car use might be modelled with a factor partly based on the statement “I like driving” (Handy et al. 2005; e.g., Ettema and Nieuwenhuis 2017). Unsurprisingly, this statement tends to be a strong predictor of driving. This relationship is intuitively obvious, however, and the strength of this predictor will mask the potentially more interesting relationships (i.e. factors that cause a person to both like driving and use a car). Furthermore, these types of attitudes are likely endogenous, partially caused by engaging in the behavior in question.

Findings

This review includes 158 papers from the travel behavior literature. We first establish that attitudinal data improve travel behavior models and discuss the limitations of this conclusion. We then review the different types of attitudes found in the literature and their relevance for different travel outcomes. Finally, we examine the global distribution of papers as well as how findings differ between continents.

How important are attitudes for predicting travel behavior?

Our review indicates that attitudes play an important role in travel decisions. In fact, some papers find that attitudes have stronger relationships with certain travel outcomes than sociodemographics (Belgiawan et al. 2016) or the built environment (Kitamura et al. 1997; Kamruzzaman et al. 2013; de Abreu e Silva 2014; Ye and Titheridge 2017). The most convincing evidence for the importance of attitudes comes from researchers who perform their full analyses twice, either once with attitudes and once without, or once with only attitudes and once with all explanatory variables.

Table 2 summarizes key aspects of 12 studies that perform this explicit comparison, representing 34 models. It is difficult to draw generalized conclusions from this set of studies beyond a strong consensus that attitudes matter. Each study uses a unique combination of dependent variables, demographic controls, attitudes, and estimation methods, and results regarding the level of importance of attitudes are uneven across studies. Thus, it remains unclear which attitudes matter most, and for which transportation choices.

While the contribution of attitudes to goodness-of-fit is only quantifiable when two models are estimated, we can evaluate whether attitudinal factors were statistically significant in papers without a comparison model. Of the literature reviewed here, only 2 out of 158 papers did not find attitudes to be significant anywhere in their research (Kamruzzaman et al. 2016; Ding et al. 2017), while two did not report the significance of latent attitudes in their models (Giles-Corti et al. 2013; Kroesen 2019). Even though significant results may be more likely to be published (Rothstein et al. 2005), the sheer volume of statistically significant attitudes suggests that they are important predictors of transport choices.

This seemingly overwhelming evidence might be misleading, however. Most articles evaluate multiple attitudinal factors, and test them in multiple models, which can lead to multiple-testing bias—where some explanatory variables are statistically significant purely by chance, due to the large number of tests conducted (Dmitrienko et al. 2009). This is exacerbated by the practice of removing insignificant variables from final models without noting which variables were removed, making it impossible to apply correction factors for multiple testing.

In light of this issue, we conducted the following analysis to conservatively evaluate the statistical significance of attitudinal factors. We assumed that if an attitudinal factor was created in a factor analysis, it was tested in every model in a paper, excluding models specifically marked as comparison models without attitudes. We then recorded how many significant attitudinal factors (at the p < 0.05 level) were reported in every individual model.Footnote 2 We estimate that attitudinal factors were entered into models 2621 times in our selection of literature and were found significant 1195 times. This back-of-the-envelope calculation allows us to conservatively estimate that attitudes are statistically significant in models of transport choices 46% of the time.

Some papers include many attitudes, exacerbating multiple testing concerns. When we remove papers that identify more than 10 attitudinal factors in their factor analysis (about 20% of papers in this review), we find that the rate of significance for attitudes increases to 54%.

These statistics show that attitudes are more often than not significant predictors of transport choices. When a small number of attitudes is carefully selected based on theoretical relationships with the transport choice of interest, statistical significance is more likely than not.

In some cases, attitudinal variables may be proxying for standard sociodemographic variables that are not included. Unfortunately, 34% of papers do not control for income in their models, 24% do not control for gender, 18% do not control for age, and 54% do not control for household size.

Nevertheless, it is clear that attitudes contribute to the predictive ability of models of transport choices. Improved methodologies such as performing analyses with and without attitudes, including sociodemographics in models, using small, theoretically justified sets of attitudes, and reporting insignificant coefficients will improve estimates of the relationships between attitudes and transport choices.

Which attitudes are most relevant for predicting different transport choices?

Not every transport-related attitude is likely to be predictive of every transport-related choice. To develop surveys that capture the information needed to address particular research or policy questions, it is important to know which attitudes are most relevant for which transport choices. This section analyses which types of attitudes have been successfully used to model five major transport-related choices: mode choice, vehicles miles traveled, residential location choice, vehicle ownership, and vehicle type choice. This will be useful to modelers deciding which questions from STAMP (Appendix A) will be useful in their models.

Mode choice

In the reviewed literature, attitudes are most often used in models of mode choice. There are two primary reasons researchers include attitudes in these models. Many directly evaluate the relationships between attitudes and mode choice. Others use attitudes to control for residential self selection—that is, whether people choose to travel in a particular way due to neighborhood built environment, or whether they choose neighborhoods based on how they prefer to travel (Cao et al. 2009a; Lin et al. 2017). The goal of these studies is not to estimate the extent to which attitudes predict mode choices, but to reduce bias in estimates of the relationship between mode choices and the built environment (Aston et al. 2020b). There are a few studies—notably Kitamura et al. (1997)—that aim to do both.

Mode liking

An oft-used and highly predictive attitudinal factor is the attitude towards the mode of interest. Attitudinal statements are often as simple as “I like walking” (e.g., Cao et al. 2009b; Guan and Wang 2019). Unsurprisingly, positive attitudes towards a mode are associated with increased likelihood of using the chosen mode and decreased likelihood of choosing other modes (Handy et al. 2005; Cao et al. 2007; Maldonado-Hinarejos et al. 2014; Ettema and Nieuwenhuis 2017; De Vos et al. 2018). As discussed earlier, including them in predictive models introduces concerns about endogeneity and may render more important relationships insignificant.

Environmentalism

Environmental concerns are another prevalent predictor of mode choice. People who are more concerned about the environment are more likely to choose sustainable modes, such as walking, biking, and public transportation, as opposed to driving (Kitamura et al. 1997; Mokhtarian et al. 2001; Schwanen and Mokhtarian 2005a; Etminani-Ghasrodashti and Ardeshiri 2015; Kim et al. 2017; Roberts et al. 2018). However, some researchers have suggested that this attitude is often less important than other motivators such as comfort or convenience (Geng et al. 2017).

Comfort

Many surveys report that comfort is an important motivator for mode choice, particularly for public transit use (Vredin Johansson et al. 2006; Hu et al. 2015; Ababio-Donkor et al. 2020). Comfort encompasses a broad array of questions, from “public transport is comfortable” to “privacy is important to me when choosing how I get around” to “driving is stressful”. Questions about comfort are often specific to a mode.

Convenience

Convenience can be a strong predictor of behavior—people tend to choose modes that are convenient, given their abilities and geographical context. Examples of the types of questions in this category include “bicycling is fast for local trips,” “it is inconvenient to commute without a car,” and “public transport is conveniently located to most of my destinations.” Questions about convenience are usually specific to a mode.

Many convenience questions refer to perceptions of transport options and the built environment. People who agree with “There are bike lanes easy to access in my neighborhood” are likely to also bicycle more (Park and Akar 2019). People who perceive that there is “no public transit where [they] live” are more likely to drive more (Habib and Zaman 2012). Perceived transport and built environment measures capture personal characteristics and attitudes that relate to mode convenience and safety that objective measures do not (e.g., comfort riding a bike alongside traffic). Objective measures are generally preferred in practice, but future research should explore when and how perceptions deviate from reality.

Safety

Safety is another attitude that is often included in models of mode choice. Sometimes, surveys ask generally about safety (Cao et al. 2006, 2009b; Xia et al. 2017; Ye and Titheridge 2017; Gabrhel 2019; Guan and Wang 2019). Others specifically ask about traffic safety (Kuppam et al. 1999; Popuri et al. 2011; Adams et al. 2013; Noland and Dipetrillo 2015), personal safety from crime (Kuppam et al. 1999; Parra et al. 2011), security from bicycle theft (Namgung and Jun 2019; Park and Akar 2019), or the presence of infrastructure for safety (Giles-Corti et al. 2013; Lee 2013; Acheampong and Siiba 2018; Sottile et al. 2019). Questions about safety are almost always specific to a particular mode, usually active travel. Perceiving active modes as safe is generally associated with increased usage, but one study (Gabrhel 2019) found the opposite—possibly because people who do cycle are more aware of the safety concerns present on the road.

Self-image

Although practical concerns such as convenience, comfort, and safety are important predictors of mode, this choice is also dependent on more subjective perceptions. Europeans in particular are more likely to bicycle if they self-identify with bicycling or see it as socially desirable (Lois et al. 2015; Barberan et al. 2017a; Ramezani et al. 2018). In a similar way, North Americans who pride themselves on being car owners or enjoy the status of driving tend to own more cars and use them more heavily relative to other modes (Schwanen and Mokhtarian 2005a; Haustein and Jensen 2018; Moody and Zhao 2019).

Residential preferences

Some studies of mode choice include attitudinal constructs that measure preferences about neighborhood type or built environment characteristics (Kitamura et al. 1997; Etminani-Ghasrodashti et al. 2018b, a). These may be relevant to mode choice outcomes because people who hold these preferences may tend to choose to live in neighborhoods where certain modes are more or less accessible.

Habit

Habits can play a strong role in decisionmaking, especially for day-to-day decisions that are made rapidly (Triandis 1979; Kahneman 2011). Evaluating the role of habit using revealed-preference data can be difficult, however; it is hard to know if repeated behaviors are due to habits or unobserved contributors to the decision that do not vary over time. Attitudes can improve on this situation by asking respondents directly about their habits, as opposed to inferring them from behavior. For instance, Ramos et al. (2020) include a “driving habit” factor in their models, including questions such as “using a car is something I don’t need to thing about” and “using a car is a part of my routine.” They find this factor to be predictive of trip frequency for a variety of purposes. Even more so than with other attitudes, however, bidirectional causality is a concern with habits—habits are the result of past choices. Even habits measured using attitudinal statements may reflect other unmeasured factors that influenced these past behaviors, and may continue to influence current behavior.

Vehicle miles traveled

Vehicle miles or kilometers traveled is the subject of a small number of papers. This outcome tends to be predicted by many of the same attitudes that also predict mode choice, especially mode-liking (Handy et al. 2005; Cao et al. 2007; Frank et al. 2007; Aditjandra et al. 2010; Banerjee and Hine 2016; Circella et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017), residential preferences (Schwanen and Mokhtarian 2005a; Cao et al. 2007; Aditjandra et al. 2010; Ewing et al. 2016; Jamal et al. 2017), and environmentalism (Golob and Hensher 1998; Schwanen and Mokhtarian 2005a; Jamal et al. 2017; Circella et al. 2017). One unique predictor of vehicle miles or kilometers traveled is a general (dis)like of travel (Cao et al. 2007; Jamal et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017).

Residential location choice

Residential location choice is considered a transport-related choice because the characteristics of one’s residential environment have a consistent, well-documented effect on travel choices (Cao et al. 2009a; Ewing and Cervero 2010; Salon et al. 2012; Guan et al. 2019; Aston et al. 2020a).

Preference for access

One major predictor of residential location choice is a preference for access, with questions such as “having shops and services within walking distance of my home is important to me” and “I would like a neighborhood with easy access to public transport service”. In general, preferences for both overall accessibility and access to specific locations like health clinics and shops are associated with living in city centers or walkable, transit-accessible neighborhoods (Berkoz et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2017; Wolday et al. 2018, 2019; Guan and Wang 2019). However, Wolday et al. (2018) found that preferences for access to some locations, such as shopping malls and outdoor exercise facilities, have a negative association with living in these neighborhoods, presumably because of the prevalence of these destinations in suburban areas.

Mode liking

As discussed in above, attitudes such as “pro-biking” or “pro-car” are most often used in models of mode choice. However, these questions are also common predictors of residential location choice, and do not present the same concerns about self-evident relationships that they do in mode choice models. Having a “pro-car” or “pro-driving” attitude is associated with living in less accessible areas or neighborhoods further from the city center (de Abreu e Silva 2014; Phani Kumar et al. 2018; Guan and Wang 2019), while preferences for active travel or public transit are associated with the opposite (de Abreu e Silva 2014; Chen et al. 2017; De Vos et al. 2019). However, these attitudes are often insignificant in residential location choice models, despite being justified theoretically.

Closely related to modal preferences is a desire for transit access. Usually defined as a preference for nearby transit infrastructure such as bus stops or train stations, this attitude is also positively correlated with residence in central neighborhoods (Cao and Ermagun 2017; Chen et al. 2017; Wolday et al. 2018, 2019).

Neighborhood social aspects

Two less common predictors of residential location choice are the social features and family friendliness of a neighborhood. Wolday et al. (2018, 2019) found that the desire to live near family and friends was associated with a lower likelihood of moving to or living in a transit-rich neighborhood. However, one study has found an association between residence in urban areas and a preference for socializing opportunities within the neighborhood (Chen et al. 2017). The effect of a preference for family-oriented neighborhoods is more consistent in the literature: the desire for either a child-friendly neighborhood in general or specific characteristics such as a private backyard tend to decrease the likelihood of choosing to live in a transit-rich neighborhood (Wolday et al. 2018, 2019).

Vehicle ownership

Convenience

Individuals who perceive car travel as convenient are more likely to own or purchase a car (Belgiawan et al. 2016; He and Thøgersen 2017). However, individuals who see cars as solely functional tools are less likely to own them (Zhou and Wang 2019), likely because other motivations for car purchase such as social value or enjoyment of driving do not factor into these individuals’ decisions.

Residential preference

Residential preferences play a significant role in car ownership, with a preference for accessible, dense neighborhoods being correlated with lower rates of car ownership (Ewing et al. 2016; Kim and Mokhtarian 2018), possibly because these people choose to live in neighborhoods where non-car travel is more convenient.

Perception of alternative modes

An important predictor of car ownership is one’s perception of alternative modes, especially public transport (Ho and Yamamoto 2014; Belgiawan et al. 2016; He and Thøgersen 2017; Kim and Mokhtarian 2018). These studies found that viewing public transport unfavorably was usually associated with higher rates of car ownership. Car-dependence attitudes, in which respondents feel they cannot get around well without a car, are predictive of car ownership as well (Belgiawan et al. 2016; Ao et al. 2019a).

Vehicle type choice

Two classes of dependent variables are generally used in models of vehicle type choice. Some studies examine the relationship between attitudes and the vehicle body type that a respondent prefers, such as an SUV, sedan, or sports car. This literature is small and heterogeneous, with few well supported conclusions. One observable trend is that purchasers of luxury and sports cars tend to be more concerned with social status (Choo and Mokhtarian 2004; Mohamed et al. 2018; Tsouros and Polydoropoulou 2020).

A second category of studies are primarily interested in what vehicle fuel type a respondent prefers, such as gas, electric, or biodiesel. Environmental concern is by far the attitude most frequently used to predict purchase or ownership of alternative fuel vehicles (Sangkapichai and Saphores 2009; Jensen et al. 2013; Daziano and Bolduc 2013; Kim et al. 2014; Mohamed et al. 2016, 2018; Haustein and Jensen 2018; He et al. 2018; Nie et al. 2018; Soto et al. 2018; Ghasri et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2019; Tsouros and Polydoropoulou 2020). Enjoyment of new technologies (Kim et al. 2014; He et al. 2018; Soto et al. 2018; Tsouros and Polydoropoulou 2020), a concern for the social value of electric vehicles (Mohamed et al. 2016, 2018; Haustein and Jensen 2018; He et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2019; Tsouros and Polydoropoulou 2020), and perceived costs or savings (Kim et al. 2014; He et al. 2018; Huang and Ge 2019; Xu et al. 2019) are common predictors as well. Perceived behavioral control presents a major barrier to electric vehicle adoption. Electric vehicles are less popular among those who are sensitive to operational hassles such as long charging times, difficulty finding charging stations, or short battery life (Kim et al. 2014, 2015; Mohamed et al. 2016, 2018; Haustein and Jensen 2018; He et al. 2018; Ghasri et al. 2019; Huang and Ge 2019; Xu et al. 2019).

How does the attitude-travel behavior research vary by geography?

Although research on attitudes and travel behavior spans the globe, the geographic distribution of studies is uneven. Table 3 shows the geographic distribution of the studies we reviewed. It also shows what percentage of the papers in each region cover particular topics (one paper may cover multiple topics). Despite differences in focus, studies in all regions find attitudes to be significant.

Europe and North America are both overrepresented in the literature, with each represented in more studies than all other regions combined. Even within these regions, most studies focus on western Europe and the United States. Asia is also fairly well-studied, although biased toward East Asia. India, Australia, the Middle East, and the global South are underrepresented in this literature. Therefore, the conclusions reported in this review apply primarily to Europe, North America, East Asia, and, to a lesser extent, Australia.

Differences by geography do appear in Table 3. Some of these are due to differing contexts between regions. Vehicle ownership is much more heavily studied in East Asia than in other contexts (Kim et al. 2015; Verma et al. 2016; He and Thøgersen 2017; Guan and Wang 2019). This is likely a result of the rapid motorization that Asia is currently undergoing (Wang et al. 2012).

Rural mobility is also more studied in Asia than Europe or North America (Ao et al. 2019a, b), probably because this region is still urbanizing. Bicycling is heavily studied in Europe, likely due to relatively high cycling mode share (Buehler and Pucher 2012).

Other differences appear to result from idiosyncratic differences in the interests and professional networks of researchers in various regions. For example, relocation studies that exploit residential moves to isolate the effects of attitudes and the built environment are more common in Europe, whereas a significant body of North American research investigates residential self-selection and travel behavior using attitudinal variables.

Few studies have been replicated in different geographic contexts, making direct comparisons of the effects of attitudes on travel difficult. Exceptions include Aditjandra et al. (2010), who replicated Handy et al.’s (2005) US study in the UK, finding that built environment measures were significant predictors of travel behavior even after controlling for travel attitudes in the UK, whereas they were not in the US. Van et al. (2014) conducted a survey in six East Asian countries, and found that in less developed countries, the perception of social orderliness of public transport was a strong motivating factor for public transport use, whereas in more developed countries, instrumental/utilitarian factors were more important. We recommend that more researchers replicate studies across geographic contexts to allow for these types of comparisons. Relying on STAMP will help make research comparable across geographies.

Methodological suggestions

Reducing heterogeneity in attitudinal questions

A major obstacle in the literature is widespread heterogeneity in attitudinal statements used by different researchers. This is a barrier to drawing conclusions from the body of research as a whole. Our contribution is the development of STAMP (Appendix A), a list of recommended attitudinal questions that capture the major constructs investigated in this literature. Most questions in STAMP are sourced directly from existing work or are only lightly modified, so the majority of the protocol has already received some validation. We encourage drawing questions from STAMP in survey development, allowing attitudes to be compared across studies.

Selecting theoretically defensible attitudes

Most studies in this literature are based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen 1991), although this theory is somewhat intuitive and so widespread in the literature that it does not always receive a direct citation. Regardless of whether authors discuss the psychosocial theories which underpin their work, they should ensure that the attitudes they select have a theorized causal link with travel outcomes. Most but not all papers clearly establish the theoretical relevance of their attitudinal variables to the outcome variable.

We advise against the use of “mode-liking” questions on surveys to predict mode choice. These questions introduce bias, obscure more important results, and at best capture relationships that are already well-established and relatively intuitive. As a caveat to this recommendation, however, we note that these questions are often worth including when the outcome variable of interest is not mode choice.

Often, researchers include many attitudinal factors in their models. However, this leads to concerns about multiple-testing bias. The inclusion of attitudes without theoretical justification also contributes to concerns about endogeneity, since the direction of causality is not theoretically clear in these cases. We recommend researchers use a smaller number of theoretically justified attitudinal factors in their models.

A common problem with the questions in this literature is that they use the word “travel” to refer to daily transportation. While this meaning is common in a research context, to the general public the word “travel” generally refers to long-distance travel. For this reason, we recommend that researchers avoid this wording, and we have avoided it in STAMP.

Statistical methodology

To clarify the contribution of attitudes to predicting travel behavior, we recommend that all researchers include sociodemographic controls and perform their analyses twice, once with only the sociodemographic controls and once with both sociodemographics and attitudes. This is the only way in which the contribution of attitudes to a model’s predictive power can be understood. The inclusion of a complete set of sociodemographics ensures that variation in the data attributable to observable characteristics is not assigned to attitudes.

We also strongly recommend against the use of stepwise regression, also known as best subset selection, a technique in which explanatory variables are introduced into or removed from a model in stages, with only the most significant ones being retained. This practice can distort results, make significance tests unreliable, and result in models that lack theoretical justification (Thompson 1995).

Less egregious but far more common than stepwise regression is the removal of statistically insignificant variables from final models, or the suppression of insignificant coefficients even if the model was estimated with them, which can lead to selective representation of larger effect sizes (Aston et al. 2020b). If insignificant coefficients are suppressed for readability, but not removed from the model, the full model specification should be included in an appendix.

Conclusion and a research agenda

This article presents the state of the literature on the relationship between attitudes and transport choices. We summarize main findings regarding the overall importance of attitudes to predict transport-related choices, which attitudes are commonly included in models of transport choices, and how these relationships vary across the globe. We identify major challenges that prevent us from drawing further conclusions, and provide suggestions to address these in future research. In particular, STAMP (Appendix A) provides a comprehensive protocol for developing survey instruments that will reduce heterogeneity in attitudinal measurement. We now conclude with a research agenda to address understudied areas in this literature.

Longitudinal studies

Most of the studies in this literature use cross-sectional samples, which cannot easily shed light on the direction of causality between attitudes and behavior or the reliability of attitudes over time.

The lack of understanding of the direction of causality between attitudes and behavior frustrates deriving policy implications from this literature. While some research exists on this topic, more longitudinal research is needed to identify whether and how attitudes cause future behaviors. True longitudinal studies, where data is collected over a period of time, are the most useful (Panter and Ogilvie 2015; Böcker et al. 2016; Olde Kalter et al. 2020; van de Coevering et al. 2021). Quasi-longitudinal studies in which participants are asked to recall past actions can be prone to recall bias, especially over long time periods, but can nonetheless also provide insights into causal relationships between attitudes and behavior (Efthymiou and Antoniou 2017). Recall bias may be a particular concern with attitudes as they are subjective and intangible, unlike a previous neighborhood or income level.

There is relatively little research evaluating the stability of transport-related attitudes over time, and longitudinal studies will be able to contribute to this gap. The psychological literature suggests that attitudes are fairly stable, over both short (Jaccard et al. 1975; Haddock et al. 1993, p. 1108n3) and long (Craig et al. 2005; van de Coevering et al. 2021) time scales. Stability likely depends on the strength of the attitude (Krosnick 1988; Prislin 1996).

Relatively few researchers have investigated the stability of transport-related attitudes specifically. Some researchers have found stability to be moderate to low (Thøgersen 2006; Adams et al. 2013). However, more recent work suggests that transport-related attitudes are quite stable, similar to other types of attitudes, even over time periods of several months (Mirtich et al. 2021). Given that attitudes are generally correlated with transport choices, and transport choices are stable, stability of attitudes would be expected as well. Longitudinal studies over longer time frames are needed to fully understand the evolution of attitudes.

There are two potential causes of attitudinal instability. One is that attitudes truly do change over time. The other is that there may be random measurement error in attitudes; if this error is sufficiently large, it may produce unstable measurements even in the presence of underlying, stable attitudes. The fact that attitudes appear to be relatively stable suggests neither of these are likely to be the case—underlying attitudes are stable over the short-to-medium term, and random errors in measurement are not sufficient to mask underlying attitudes.

Experimental studies

Policy interventions to affect attitudes and therefore behavior are potentially promising. However, it is not clear how difficult it is to influence attitudes through policy. We urge researchers to undertake studies that attempt to change people’s transport-related attitudes, for instance through providing additional information about transport options and issues, and measure transportation outcomes. This requires careful consideration for the ethical issues implied. These study designs can also contribute to understanding the causal relationship between attitudes and behavior, and should be conducted as randomized control trials.

Forecasting of attitudes

To support long-range planning, travel model input variables must be forecast into the future (Ortúzar and Willumsen 2011, ch. 15). While methods for forecasting land use and demographic inputs are well-developed, it is unclear how to forecast future attitudes. Methods developed by psychologists to model the evolution of attitudes have generally been applied to short-term forecasting of specific attitudes, using high-fidelity data on social relationships—not something typically available to transport planners (e.g., Friedkin and Johnsen 1999). We encourage the study of methods for forecasting attitudes into the future.

Research in the global South

The global South is extremely understudied in the travel behavior literature, with research from South America or Africa appearing in only 4 of 158 reviewed articles. However, much could be gained from reducing this geographic bias. Africa is the most quickly urbanizing continent (Elmqvist et al. 2013) and South America, while highly urbanized, remains relatively nonmotorized (Hidalgo and Huizenga 2013); these contexts offer the opportunity to understand how the urbanization and motorization processes shape travel behavior. Additionally, modes such as informal transit and motorcycles which are not widespread in Europe or North America can be studied in the South American and African contexts, where they are much more prominent (Adoga 2012; Finn 2012; Hagen et al. 2016).

Availability of data and material

Database developed for this project is publicly available at https://files.indicatrix.org/attitudes.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Unless otherwise indicated, attitudinal statements used as examples are drawn from STAMP; see Appendix A for citations to the original sources.

In cases where a structural equation model is specified so that an attitudinal factor has a direct effect on multiple dependent variables, the attitude is counted as significant if any of its effects on dependent variables in that model are significant, or there is a pathway to the dependent variable consisting of only significant effects. Excluding papers that fit structural equation models leads to a slightly lower significance rate (41%).

References

Ababio-Donkor, A., Saleh, W., Fonzone, A.: Understanding transport mode choice for commuting: the role of affect. Transp Plan Technol (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/03081060.2020.1747203

Acheampong, R.A., Siiba, A.: Examining the determinants of utility bicycling using a socio-ecological framework: an exploratory study of the Tamale Metropolis in Northern Ghana. J Transp Geogr 69, 1–10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.04.004

Adams, E.J., Goodman, A., Sahlqvist, S., et al.: Correlates of walking and cycling for transport and recreation: Factor structure, reliability and behavioural associations of the perceptions of the environment in the neighbourhood scale (PENS). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-87

Aditjandra PT, Mulley CA, Nelson JD (2010) Neighbourhood design impact on travel behavior: a comparison of US and UK experience. Projections 28–56

Aditjandra, P.T., Mulley, C., Nelson, J.D.: The influence of neighbourhood design on travel behaviour: empirical evidence from North East England. Transp Policy 26, 54–65 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.05.011

Adnan, M., Altaf, S., Bellemans, T., et al.: Last-mile travel and bicycle sharing system in small/medium sized cities: user’s preferences investigation using hybrid choice model. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 10, 4721–4731 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-018-0849-5

Adoga, A.: The motorcycle: a dangerous contraption used for commercial transportation in the developing world. Emerg. Med. (2012). https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7548.1000e109

Ajzen, I.: The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50, 179–211 (1991)

Akar, G., Clifton, K.J.: Influence of individual perceptions and bicycle infrastructure on decision to bike. Transp Res Rec 2140, 165–172 (2009). https://doi.org/10.3141/2140-18

Ao, Y., Yang, D., Chen, C., Wang, Y.: Effects of rural built environment on travel-related CO2 emissions considering travel attitudes. Transp Res Part D 73, 187–204 (2019a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.07.004

Ao, Y., Yang, D., Chen, C., Wang, Y.: Exploring the effects of the rural built environment on household car ownership after controlling for preference and attitude: evidence from Sichuan, China. J Transp Geogr 74, 24–36 (2019b). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.11.002

Aston, L., Currie, G., Kamruzzaman, M.D., et al.: Study design impacts on built environment and transit use research. J Transp Geogr 82, 102625 (2020b). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.102625

Aston, L., Currie, G., Delbosc, A., et al.: Exploring built environment impacts on transit use: an updated meta-analysis. Transp Rev (2020a). https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2020.1806941

Atasoy, B., Glerum, A., Bierlaire, M.: Attitudes towards mode choice in Switzerland. DISP 49, 101–117 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2013.827518

Bagley, M.N., Mokhtarian, P.L.: The impact of residential neighborhood type on travel behavior: a structural equations modeling approach. Ann. Reg. Sci. 36, 279–297 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/s001680200083

Banerjee, U., Hine, J.: Interpreting the influence of urban form on household car travel using partial least squares structural equation modelling: some evidence from Northern Ireland. Transp Plan Technol 39, 24–44 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/03081060.2015.1108081

Barajas JM (2019) Perceptions, people, and places: influences on cycling for Latino immigrants and implications for equity. J Plan Educ Res 0739456X19864714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19864714

Barberan A, de Abreu e Silva J, Monzon A (2017b) Factors influencing bicycle use: a binary choice model with panel data. Transp Res Procedia pp 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2017.12.097

Belgiawan, P.F., Schmöcker, J.-D., Fujii, S.: Understanding car ownership motivations among Indonesian students. Int J Sustain Transp 10, 295–307 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2014.921846

Berkoz, L., Turk, S.S., Kellekci, O.L.: Environmental quality and user satisfaction in mass housing areas: the case of Istanbul. Eur Plan Stud 17, 161–174 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310802514086

Bigazzi, A.Y., Gehrke, S.R.: Joint consideration of energy expenditure, air quality, and safety by cyclists. Transp. Res. Part F. 58, 652–664 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.07.005

Böcker, L., Dijst, M., Faber, J.: Weather, transport mode choices and emotional travel experiences. Transp Res Part A 94, 360–373 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.09.021

Bouscasse, H., Joly, I., Bonnel, P.: How does environmental concern influence mode choice habits? A mediation analysis. Transp Res Part D 59, 205–222 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2018.01.007

Buehler, R., Pucher, J.: International overview: cycling trends in Western Europe, North America, and Australia. In: City cycling, pp. 9–29. MIT Press, Cambridge (2012)

Cameron, A.C., Trivedi, P.K.: Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, New York (2005)

Cao, X., Ermagun, A.: Influences of LRT on travel behaviour: a retrospective study on movers in Minneapolis. Urban Stud 54:2504–2520 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016651569

Cao, X., Handy, S.L., Mokhtarian, P.L.: The influences of the built environment and residential self-selection on pedestrian behavior: evidence from Austin, TX. Transportation 33:1–20 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-005-7027-2

Cao, X., Mokhtarian, P.L., Handy, S.L.: Do changes in neighborhood characteristics lead to changes in travel behavior? A structural equations modeling approach. Transportation 34:535–556 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-007-9132-x

Cao, X., Mokhtarian, P.L., Handy, S.L.: The relationship between the built environment and nonwork travel: a case study of Northern California. Transp Res Part Policy Pract 43:548–559 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2009.02.001

Cao, X., Mokhtarian, P.L., Handy, S.L.: Examining the impacts of residential self-selection on travel behaviour: a focus on empirical findings. Transp Rev 29:359–395 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640802539195

Chen, F., Wu, J., Chen, X., Wang, J.: Vehicle kilometers traveled reduction impacts of Transit-Oriented Development: Evidence from Shanghai City. Transp Res Part D 55, 227–245 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.07.006

Chng, S., White, M.P., Abraham, C., Skippon, S.: Consideration of environmental factors in reflections on car purchases: Attitudinal, behavioural and sociodemographic predictors among a large UK sample. J Clean Prod 230, 927–936 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.179

Choo, S., Mokhtarian, P.L.: What type of vehicle do people drive? The role of attitude and lifestyle in influencing vehicle type choice. Transp Res Part A 38, 201–222 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2003.10.005

Chorus, C.G., Kroesen, M.: On the (im-)possibility of deriving transport policy implications from hybrid choice models. Transp Policy 36, 217–222 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.09.001

Circella G, Alemi F, Tiedeman K, et al (2017) What affects millennials’ mobility? PART II: the impact of residential location, individual preferences and lifestyles on young adults’ travel behavior in California

Conway, M.W., Salon, D., da Silva, D.C., Mirtich, L.: How Will the COVID-19 pandemic affect the future of urban life? Early evidence from highly-educated respondents in the United States. Urban Sci 4, 50 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci4040050

Craig, S.C., Martinez, M.D., Kane, J.G.: Ambivalence and response instability. In: Craig, S.C., Martinez, M.D. (eds.) Ambivalence and the structure of political opinion, pp. 55–71. Palgrave Macmillan, New York (2005)

Curto, A., De Nazelle, A., Donaire-Gonzalez, D., et al.: Private and public modes of bicycle commuting: a perspective on attitude and perception. Eur J Public Health 26, 717–723 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv235

Daisy, N.S., Habib, M.A.: Investigating the role of built environment and lifestyle choices in active travel for weekly home-based nonwork trips. Transp Res Rec (2015). https://doi.org/10.3141/2500-15

Dalkey, N., Helmer, O.: An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of Experts. Manag Sci 9, 458–467 (1963)

Daziano, R.A., Bolduc, D.: Incorporating pro-environmental preferences towards green automobile technologies through a Bayesian hybrid choice model. Transp Transp Sci 9, 74–106 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/18128602.2010.524173

de Abreu e Silva J (2014) Spatial self-selection in land-use travel behavior interactions: accounting simultaneously for attitudes and socioeconomic characteristics. J Transp Land Use 7:63–84. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.v7i2.696

de Dios Ortúzar J, Willumsen LG (2011) Modelling Transport. Wiley, Chichester, UK

de Vos, J., Ettema, D., Witlox, F.: Changing travel behaviour and attitudes following a residential relocation. J Transp Geogr 73, 131–147 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.10.013

de Vos, J., Schwanen, T., Van Acker, V., Witlox, F.: Do satisfying walking and cycling trips result in more future trips with active travel modes? An exploratory study. Int J Sustain Transp 13, 180–196 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2018.1456580

De Vos, J., Singleton, P.A., Gärling, T.: From attitude to satisfaction: introducing the travel mode choice cycle. Transp. Rev. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1958952

Dill, J., Mohr, C., Ma, L.: How can psychological theory help cities increase walking and bicycling? J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 80, 36–51 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2014.934651

Ding, C., Chen, Y., Duan, J., et al.: Exploring the influence of attitudes to walking and cycling on commute mode choice using a hybrid choice model. J Adv Transp (2017). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8749040

Dmitrienko A, Tamhane AC, Bretz F (eds) (2009) Multiple testing problems in pharmaceutical statistics. CRC Press

Efthymiou, D., Antoniou, C.: Understanding the effects of economic crisis on public transport users’ satisfaction and demand. Transp Policy 53, 89–97 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.09.007

Elmqvist, T., Fragkias, M., Goodness, J., et al.: Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities. Springer (2013)

Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R., Ardeshiri, M.: Modeling travel behavior by the structural relationships between lifestyle, built environment and non-working trips. Transp Res Part A 78, 506–518 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2015.06.016

Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R., Paydar, M., Ardeshiri, A.: Recreational cycling in a coastal city: Investigating lifestyle, attitudes and built environment in cycling behavior. Sustain Cities Soc 39, 241–251 (2018b). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.02.037

Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R., Paydar, M., Hamidi, S.: University-related travel behavior: young adults’ decision-making in Iran. Sustain Cities Soc 43, 495–508 (2018a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.09.011

Ettema, D., Nieuwenhuis, R.: Residential self-selection and travel behaviour: what are the effects of attitudes, reasons for location choice and the built environment? J Transp Geogr 59, 146–155 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.01.009

Ewing, R., Cervero, R.: Travel and the built environment: a meta-analysis. J Am Plann Assoc 76, 265–294 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/01944361003766766

Ewing, R., Hamidi, S., Grace, J.B.: Compact development and VMT: environmental determinism, self-selection, or some of both? Environ Plan B 43, 737–755 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813515594811

Festinger, L.: A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press, Stanford (1962)

Finn, B.: Towards large-scale flexible transport services: a practical perspective from the domain of paratransit. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 3, 39–49 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2012.06.010

Fishbein, M.: A theory of reasoned action: some applications and implications. Nebr. Symp. Motiv. 27, 65–116 (1979)

Frank, L.D., Saelens, B.E., Powell, K.E., Chapman, J.E.: Stepping towards causation: do built environments or neighborhood and travel preferences explain physical activity, driving, and obesity? Soc Sci Med 65, 1898–1914 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.053

Friedkin NE, Johnsen EC (1999) Social influence networks and opinion change. In: Advances in group processes. Jai Press, Greenwich, Conn, pp 1–29

Gabrhel, V.: Feeling like cycling? Psychological factors related to cycling as a mode choice. Trans Transp Sci 10, 19–30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5507/tots.2019.006

Geng, J., Long, R., Chen, H., et al.: Exploring multiple motivations on urban residents’ travel mode choices: an empirical study from Jiangsu Province in China. Sustain Switz (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010136

Ghasri, M., Ardeshiri, A., Rashidi, T.: Perception towards electric vehicles and the impact on consumers’ preference. Transp Res Part D 77, 271–291 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.11.003

Giles-Corti, B., Bull, F., Knuiman, M., et al.: The influence of urban design on neighbourhood walking following residential relocation: longitudinal results from the RESIDE study. Soc Sci Med 77, 20–30 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.016

Golob, T.F., Hensher, D.A.: Greenhouse gas emissions and Australian commuters’ attitudes and behavior concerning abatement policies and personal involvement. Transp Res Part D 3, 1–18 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1361-9209(97)00006-0

Guan, X., Wang, D.: Residential self-selection in the built environment-travel behavior connection: whose self-selection? Transp Res Part D 67, 16–32 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2018.10.015

Guan X, Wang D, Cao X (2019) The role of residential self-selection in land use-travel research: a review of recent findings. Transp Rev. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2019.1692965

Habib, K.M.N., Zaman, Md.H.: Effects of incorporating latent and attitudinal information in mode choice models. Transp Plan Technol 35, 561–576 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/03081060.2012.701815

Haddock, G., Zanna, M.P., Esses, V.M.: Assessing the structure of prejudicial attitudes: the case of attitudes toward homosexuals. J Pers Soc Psychol 65, 1105 (1993)

Hagen, J.X., Pardo, C., Valente, J.B.: Motivations for motorcycle use for Urban travel in Latin America: a qualitative study. Transp. Policy. 49, 93–104 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.04.010

Handy S, Cao X, Mokhtarian PL (2005) Correlation or causality between the built environment and travel behavior? Evidence from Northern California. Transp Res Part D 10:427–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2005.05.002

Haustein, S., Jensen, A.F.: Factors of electric vehicle adoption: a comparison of conventional and electric car users based on an extended theory of planned behavior. Int J Sustain Transp 12, 484–496 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2017.1398790

He, S.Y., Thøgersen, J.: The impact of attitudes and perceptions on travel mode choice and car ownership in a Chinese megacity: the case of Guangzhou. Res Transp Econ 62, 57–67 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2017.03.004

He, X., Zhan, W., Hu, Y.: Consumer purchase intention of electric vehicles in China: the roles of perception and personality. J Clean Prod 204, 1060–1069 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.260

Hidalgo, D., Huizenga, C.: Implementation of sustainable urban transport in Latin America. Res. Transp. Econ. 40, 66–77 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2012.06.034

Ho CQ, Yamamoto T (2014) The role of attitudes and public transport service on vehicle ownership in Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam

Huang, X., Ge, J.: Electric vehicle development in Beijing: an analysis of consumer purchase intention. J Clean Prod 216, 361–372 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.231

Hu, X., Zhao, L., Wang, W.: Impact of perceptions of bus service performance on mode choice preference. Adv Mech Eng 7, 1–11 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814015573826

Ingvardson, J.B., Nielsen, O.A.: The relationship between norms, satisfaction and public transport use: a comparison across six European cities using structural equation modelling. Transp Res Part A 126, 37–57 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.05.016

Jaccard, J., Weber, J., Lundmark, J.: A multitrait-multimethod analysis of four attitude assessment procedures. J Exp Soc Psychol 11, 149–154 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(75)80017-5

Jamal S, Habib MA, Khan NA (2017) Does the use of smartphone influence travel outcome? An investigation on the determinants of the impact of smartphone use on vehicle kilometres travelled, pp 2690–2704

Jensen, A.F., Cherchi, E., Mabit, S.L.: On the stability of preferences and attitudes before and after experiencing an electric vehicle. Transp Res Part D 25, 24–32 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2013.07.006

Johansson, M.V., Heldt, T., Johansson, P.: The effects of attitudes and personality traits on mode choice. Transp Res Part A 40, 507–525 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2005.09.001

Kahneman, D.: Thinking. Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York (2011)

Kamruzzaman, M., Baker, D., Washington, S., Turrell, G.: Residential dissonance and mode choice. J Transp Geogr 33, 12–28 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.09.004

Kamruzzaman, M., Baker, D., Turrell, G.: Do dissonants in transit oriented development adjust commuting travel behaviour? Eur J Transp Infrastruct Res 15, 66–77 (2015a)

Kamruzzaman, M., Shatu, F.M., Hine, J., Turrell, G.: Commuting mode choice in transit oriented development: disentangling the effects of competitive neighbourhoods, travel attitudes, and self-selection. Transp Policy 42, 187–196 (2015b). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2015.06.003

Kamruzzaman, M., Baker, D., Washington, S., Turrell, G.: Determinants of residential dissonance: implications for transit-oriented development in Brisbane. Int J Sustain Transp 10, 960–974 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2016.1191094

Kim, S.H., Mokhtarian, P.L.: Taste heterogeneity as an alternative form of endogeneity bias: investigating the attitude-moderated effects of built environment and socio-demographics on vehicle ownership using latent class modeling. Transp Res Part A 116, 130–150 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.05.020

Kim, J., Rasouli, S., Timmermans, H.: Expanding scope of hybrid choice models allowing for mixture of social influences and latent attitudes: application to intended purchase of electric cars. Transp Res Part A 69, 71–85 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2014.08.016

Kim, D., Ko, J., Park, Y.: Factors affecting electric vehicle sharing program participants’ attitudes about car ownership and program participation. Transp Res Part D 36, 96–106 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2015.02.009

Kim, J., Rasouli, S., Timmermans, H.J.P.: The effects of activity-travel context and individual attitudes on car-sharing decisions under travel time uncertainty: a hybrid choice modeling approach. Transp Res Part D 56, 189–202 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.07.022

Kitamura, R., Mokhtarian, P.L., Laidet, L.: A micro-analysis of land use and travel in five neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area. Transportation 24, 125–158 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017959825565

Kløjgaard, M.E., Hess, S.: Understanding the formation and influence of attitudes in patients’ treatment choices for lower back pain: testing the benefits of a hybrid choice model approach. Soc Sci Med 114, 138–150 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.058

Kroesen, M.: Residential self-selection and the reverse causation hypothesis: assessing the endogeneity of stated reasons for residential choice. Travel Behav Soc 16, 108–117 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.05.002

Kroesen, M., Chorus, C.: The role of general and specific attitudes in predicting travel behaviour: a fatal dilemma? Travel Behav Soc 10, 33–41 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2017.09.004

Kroesen, M., Handy, S.L., Chorus, C.: Do attitudes cause behavior or vice versa? An alternative conceptualization of the attitude-behavior relationship in travel behavior modeling. Transp Res Part A 101, 190–202 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.05.013

Krosnick, J.A.: Attitude importance and attitude change. J Exp Soc Psychol 24, 240–255 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(88)90038-8

Kuppam, A., Pendyala, R.M., Rahman, S.: Analysis of the role of traveler attitudes and perceptions in explaining mode-choice behavior. Transp Res Rec 1676, 68–76 (1999). https://doi.org/10.3141/1676-09

Lee, J.: Perceived neighborhood environment and transit use in low-income populations. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board 2397, 125–134 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3141/2397-15

Lin, T., Wang, D., Guan, X.: The built environment, travel attitude, and travel behavior: residential self-selection or residential determination? J Transp Geogr 65, 111–122 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.10.004

Liu, Y., Ouyang, Z., Cheng, P.: Predicting consumers’ adoption of electric vehicles during the city smog crisis: an application of the protective action decision model. J Environ Psychol 64, 30–38 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.04.013

Lois, D., Moriano, J.A., Rondinella, G.: Cycle commuting intention: a model based on theory of planned behaviour and social identity. Transp Res Part F 32, 101–113 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2015.05.003

Maio GR, Haddock G, Verplanken B (2019) The Psychology of Attitudes and Attitude Change, 3rd edition. SAGE, Los Angeles

Maldonado-Hinarejos, R., Sivakumar, A., Polak, J.W.: Exploring the role of individual attitudes and perceptions in predicting the demand for cycling: a hybrid choice modelling approach. Transportation 41, 1287–1304 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-014-9551-4

Malokin, A., Circella, G., Mokhtarian, P.L.: How do activities conducted while commuting influence mode choice? Using revealed preference models to inform public transportation advantage and autonomous vehicle scenarios. Transp Res Part A 124, 82–114 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.12.015

Mirtich L, Conway MW, Salon D, et al (2021) How stable are transport-related attitudes over time? Transp Find. https://doi.org/10.32866/001c.24556

Mohamed, M., Higgins, C., Ferguson, M., Kanaroglou, P.: Identifying and characterizing potential electric vehicle adopters in Canada: a two-stage modelling approach. Transp Policy 52, 100–112 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.07.006

Mohamed, M., Higgins, C.D., Ferguson, M., Réquia, W.J.: The influence of vehicle body type in shaping behavioural intention to acquire electric vehicles: a multi-group structural equation approach. Transp Res Part A 116, 54–72 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.05.011

Mokhtarian, P.L., Salomon, I.: Modeling the desire to telecommute: the importance of attitudinal factors in behavioral models. Transp Res Part A 31, 35–50 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-8564(96)00010-9

Mokhtarian, P.L., Salomon, I., Redmond, L.S.: Understanding the demand for travel: it’s not purely “derived.” Innov Eur J Soc Sci Res 14, 355–380 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610120106147

Molin, E., Mokhtarian, P.L., Kroesen, M.: Multimodal travel groups and attitudes: a latent class cluster analysis of Dutch travelers. Transp Res Part A 83, 14–29 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2015.11.001

Moody, J., Zhao, J.: Car pride and its bidirectional relations with car ownership: case studies in New York City and Houston. Transp Res Part A 124, 334–353 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.04.005

Namgung, M., Akar, G.: Influences of neighborhood characteristics and personal attitudes on university commuters’ public transit use. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board 2500, 93–101 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3141/2500-11

Namgung, M., Jun, H.-J.: The influence of attitudes on university bicycle commuting: considering bicycling experience levels. Int J Sustain Transp 13, 363–377 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2018.1471557

Nie, Y., Wang, E., Guo, Q., Shen, J.: Examining Shanghai consumer preferences for electric vehicles and their attributes. Sustain Switz (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062036

Noland, R.B., Dipetrillo, S.: Transit-oriented development and the frequency of modal use. J Transp Land Use 8, 21–44 (2015). https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2015.517

Olde Kalter, M.-J., La Paix, P.L., Geurs, K.T.: Do changes in travellers’ attitudes towards car use and ownership over time affect travel mode choice? A latent transition approach in the Netherlands. Transp Res Part A 132, 1–17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.10.015

Ory, D.T., Mokhtarian, P.L.: When is getting there half the fun? Modeling the liking for travel. Transp Res Part A 39, 97–123 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2004.09.006

Panter, J., Ogilvie, D.: Theorising and testing environmental pathways to behaviour change: natural experimental study of the perception and use of new infrastructure to promote walking and cycling in local communities. BMJ Open (2015). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007593

Park, Y., Akar, G.: Understanding the effects of individual attitudes, perceptions, and residential neighborhood types on university commuters’ bicycling decisions. J Transp Land Use 12, 419–441 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2019.1259

Parra, D.C., Hoehner, C.M., Hallal, P.C., et al.: Perceived environmental correlates of physical activity for leisure and transportation in Curitiba, Brazil. Prev Med 52, 234–238 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.12.008

Phani Kumar, P., Ravi Sekhar, C., Parida, M.: Residential dissonance in TOD neighborhoods. J Transp Geogr 72, 166–177 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.09.005

Popuri, Y., Proussaloglou, K., Ayvalik, C., et al.: Importance of traveler attitudes in the choice of public transportation to work: findings from the Regional Transportation Authority Attitudinal Survey. Transportation 38, 643–661 (2011a). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-011-9336-y

Prislin, R.: Attitude stability and attitude strength: one is enough to make it stable. Eur J Soc Psychol 26, 447–477 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199605)26:3%3c447::AID-EJSP768%3e3.0.CO;2-I

Pucher, J., Dijkstra, L.: Promoting safe walking and cycling to improve public health: lessons from the Netherlands and Germany. Am J Public Health 93, 1509–1516 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1509

Ramezani, S., Pizzo, B., Deakin, E.: An integrated assessment of factors affecting modal choice: towards a better understanding of the causal effects of built environment. Transportation 45, 1351–1387 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-017-9767-1

Ramos, É.M.S., Bergstad, C.J., Nässén, J.: Understanding daily car use: driving habits, motives, attitudes, and norms across trip purposes. Transp Res Part F 68, 306–315 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2019.11.013

Redmond, L.S., Mokhtarian, P.L.: The positive utility of the commute: modeling ideal commute time and relative desired commute amount. Transportation 28, 179–205 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010366321778

Roberts, J., Popli, G., Harris, R.J.: Do environmental concerns affect commuting choices?: Hybrid choice modelling with household survey data. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 181, 299–320 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12274

Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M (2005) Publication bias in meta-analysis. In: Publication bias in meta-analysis—prevention, assessment and adjustments. Wiley, Chichester, West Sussex, UK, p 8

Salon, D., Boarnet, M.G., Handy, S., et al.: How do local actions affect VMT? A critical review of the empirical evidence. Transp Res Part D 17, 495–508 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2012.05.006

Sangkapichai, M., Saphores, J.-D.: Why are Californians interested in hybrid cars? J Environ Plan Manag 52, 79–96 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560802504670

Schmitt, A.: Right of way: race, class, and the silent epidemic of pedestrian deaths in America. Island Press, Washington (2020)

Schwanen, T., Mokhtarian, P.L.: What if you live in the wrong neighborhood? The impact of residential neighborhood type dissonance on distance traveled. Transp Res Part D 10, 127–151 (2005a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2004.11.002

Schwanen, T., Mokhtarian, P.L.: What affects commute mode choice: neighborhood physical structure or preferences toward neighborhoods? J Transp Geogr 13, 83–99 (2005b). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2004.11.001

Schwanen, T., Mokhtarian, P.L.: Attitudes toward travel and land use and choice of residential neighborhood type: evidence from the San Francisco Bay Area. Hous Policy Debate 18, 171–207 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2007.9521598

Shirgaokar, M., Nurul Habib, K.: How does the inclination to bicycle sway the decision to ride in warm and winter seasons? Int J Sustain Transp 12, 397–406 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2017.1378779

Soto, J.J., Cantillo, V., Arellana, J.: Incentivizing alternative fuel vehicles: the influence of transport policies, attitudes and perceptions. Transportation 45, 1721–1753 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-018-9869-4

Sottile, E., Sanjust di Teulada, B., Meloni, I., Cherchi, E.: Estimation and validation of hybrid choice models to identify the role of perception in the choice to cycle. Int J Sustain Transp 13, 543–552 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2018.1490465

Stewart, A.E., Lord, J.H.: Motor vehicle crash versus accident: a change in terminology is necessary. J Trauma Stress 15, 333–335 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016260130224

Thøgersen, J.: Understanding repetitive travel mode choices in a stable context: a panel study approach. Transp Res Part A 40, 621–638 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2005.11.004

Thompson, B.: Stepwise regression and stepwise discriminant analysis need not apply here: a guidelines editorial. Educ Psychol Meas 55, 525–534 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164495055004001