Abstract

This exploratory qualitative case study analyzes the risks of misappropriation of COVID-19 relief funds managed by public agencies in the County of Los Angeles. This study documents deviance, sources of misbehavior, vulnerability factors and mitigation strategies in place to prevent fraud and corruption. Results indicate that loopholes in benefits eligibility certification led to massive levels of fraud, and that internal infrastructure and the work climate within public institutions exacerbated fraud risks. Institutional fragmentation, political pressures and human resources practices hindered the effectiveness of prevention mechanisms. Recommendations to strengthen accountability systems and institutional safeguards against fraud and ethical deviance are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethical deficits, such as corruption, conflict of interest and waste of public resources are global phenomena. Common sources of ethical risks can be found in post-scandal research. These include pernicious organizational climates that lack the ability to learn from past mistakes and adopt a learning mindset. Public agencies and the private organizations within public services delivery networks can also lack capacity to implement previously recommended actions, or secure the human-technical infrastructure to promote continuous improvement with regards to ethics and risks. Many resources are wasted during and after a corruption scandal (Liu & Mikesell, 2014).

Corruption itself can take on many forms: bribery, extortion, misappropriation, self-dealing, misuse of information, nepotism, and creating or exploiting conflict of interest (Graycar, 2015). Some forms of corruption occur openly in organizations and is difficult to prevent due to it occurring through legitimate operations (Ceresola, 2019). Some of the other consequences of corruption include erosion of public trust in government and the undermining of democratic institutions (Villoria et al., 2013). The County of Los Angeles has a workforce of approximately 100, 000 employees, and comprises 35 departments (Los Angeles, 2020). It has an annual budget of approximately $36.2 billion. Because of the pandemic, the Los Angeles County experienced a drastic loss of tax sales revenue. To meet a $935.3 million budget shortfall, the County proceeded to the elimination of thousands of positions (Daily News 2020). However, shortly thereafter, the County felt the need to hire massively – as much as 400 eligibility workers for one local agency alone – in an effort to implement pandemic relief-related programs, such as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

Unemployment fraud skyrocketed during the period of April to June 2020. Based on longitudinal trends of about 10% fraudulent claims, the Auditor General estimated that at least $87 billion of Unemployment Insurance was defraudedFootnote 1 (Department of Labor 2021). If ethical safeguards were put in place in response to this situation, such safeguards are at risk of being poorly implemented or eroding, more or less gradually. Moreover, many factors exacerbated the risks of corruption in the management of public services including pandemic-relief and unemployment claims approvals. These factors include, the pressure and urgency of approving unemployment, and other forms of emergency reliefs claims, the limited experience of many eligibility workers, and the quasi-absence of supervision reported by those in the frontlines.

The rollout of the pandemic-relief programs occurred after local governments responded with drastic measures to meet drastic revenue loss. Given the toll corruption has on already strained public resources, is as important as ever to assess the effectiveness of our public safeguards against corruption. This project is aimed at exploring workarounds, fraud, discretions, and other types of corruption, that occur through an erosion of safeguards and ambiguities present in the policies of LAC’s pandemic-relief funds managing departments. Using a qualitative methodology, we explore the risk and vulnerability factors as perceived by internal public sector stakeholders within agencies in the County of Los Angeles during the recent Pandemic.

Conceptual framework

Throughout the 20th century, the vision for anti-corruption in the American public apparatus was moved by moral, reformist, scientific and panoptical (surveillance-promoting) imperatives (Anechiarico & Jacobs 1994). During the 1900–1930 period and during the New Deal, a morally-moved, progressive vision introduced codes of conduct and standards in an effort to counter political patronage. The current risk-regimes era is characterized by the need for ethical leadership and bureaucratic transparency. Misconduct is perceived as the product of a lack of leadership support and strategic vision (Gnankob et al., 2022; Van Nierkerk, Valiquette L’Heureux & Holtzhausen, 2022). Ethical risks, in the current era, are seen by scholars of ethics as potentially curbed by an appropriate ethical climate, supportive leadership as well as sentinel entities designed to oversee the legal and moral standards in organizations (Brown & Trevino 2006).

However, in practice, accountability-seeking mechanisms, such as whistleblowing channels, or codes of conduct can fail (Cho & Song, 2015; Holtzhausen, 2012). As explained in Rose-Ackerman’s (1975) seminal work , an effective law must do more than impose heavy penalties upon the participants to the illicit bargain; since even a heavy fine whose amount is a function of the bribe paid may fail to deter corrupt activity (see Freudenburg & Gramling 2012 on the case of BP). Three mutually reinforcing processes lead to corruption’s normalization (Ashforth & Anand 2003): institutionalization, where an initial corrupt decision or act becomes embedded in structures and processes and thereby routinized; rationalization; where self-serving ideologies develop to justify and perhaps even valorize corruption; and socialization, where naïve newcomers are induced to view corruption as permissible if not desirable.

Moreover, there are factors that lead to inertia and to serious degradation of ethical commitment, such as bureaucratic protection logics, poor strategic integration of ethical values in organizations’ planning and evaluation mechanisms, and blame games (Atler, 2003; Boisvert 2018; Hood, Rostein & Baldwin, 2001). Relative independence of the public service from political imperatives is an important theme in anti-corruption literature (Van Niekerk & Dalton-Brits, 2016; Van Niekerk, Valiquette L’Heureux & Holtzhausen, 2022). Factors that increase, however, corruption levels, are geographical isolation (Campante & Do, 2014) as well as the proportion of a state’s expenditures derived from federal transfers (Fisman & Gatti, 2002).

Boisvert’s ethical risks framework

When evaluating risks of deviance and potential for social control there is a need to look into the in-situ, contextual factors. Boisvert (2018) in a study of municipal corruption, proposes three analytic dimensions for ethical risks: deviant behaviors, risk factors and mitigation/attenuation strategies. Each component is dynamically, interacting. Deviant behaviors are exacerbated by risks factors and weak mitigation strategies. This model underpins the complexity and challenge of dealing with ethical risks through formal and informal processes. Anti-corruption strategies, programs and policies can experience important distortions during their implementation phase (Graycar, 2015; Coglianese, 2012). Organizations that are designed to mitigate corruption can be themselves experiencing it (Freudenburg & Gramling, 2012). When it comes to risk networks, non-linear dynamics are at play (Stacey &Griffin, 2006). Discretion, coupled with a laisser-faire attitude pertaining to procedural probity and ethics can greatly increase opportunity for deviant (fraudulent or corrupt) behaviors. Whistleblowing, in turn, requires not only formal mechanisms, but also, psychological safety; (see Davis 2012; Lipman & Lipman, 2012; Ulmer, 2000) because blowing the whistle can often mean the loss of one’s job or, at the very least, ostracism in the workplace (Cant, 2001). Such processes are conditioned by many context-specific factors, including institutional infrastructure (policies and other formal, decisional mechanisms), values and socially-constructed perceptions and behavioral norms. A high moral propensity from civil servants is also associated with lower corruption levels (Andreoli & Leftkowitz 2009; Veetikazhi et al., 2021). Lower corruption levels were associated to factors such as a population’s education and relative wealth (Glaeser & Saks, 2006) and law and free press (Kumara & Handapangoda, 2014). These dynamic components can be categorized using Boisvert’s theory.

How crises affect ethical risks

Crises, such as natural disasters are positively associated with higher corruption levels (Yamamura, 2014; Escaleras et al., 2006, 2007; Green, 2005). Crises exacerbate ethical risks, as it may be perceived that other imperatives, such as the need to resume functions, protect core functions or overcome real or perceived threats, outweigh the need for procedural diligence and procedural justice (Vadera, Pratt & Mishra, 2013). Crises, technically should lead to greater levels of vigilance (Busenberg, 1999; Freudenburg, 1993). However, recent studies indicate that institutions do not always learn from corruption scandals, policy failures or crisis (Van Niekerk, Valiquette L’Heureux & Holtzhausen, 2022). As we shall see next, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused important changes and challenges to local governments in Los Angeles. This study will build on prior research to analyze how these changes were managed and to what extent the institutions responsible for distributing COVID-19 relief funds ensured that the funds were being allocated in an efficient, yet, integrity-driven manner.

Background: the case of Los Angeles City & County

California’s population is estimated at around 40 million people (U.S. Census Bureau 2022). In March of 2020, the State of California issued Stay-at-home (or shelter-in-place) orders, that had a series of very important, never before seen, ripple effects. The Golden State’s finances were impacted deeply by the COVID-19 pandemic. In April 2020 alone, 2.4 million people got laid off in California. In comparison, in the last economic recession, between December 2008 and January 2009, 132,800 jobs were lost (Roosevelt, 2020). The California Development Department (EDD) had to process, between March 2020 and January 2021, 19.5 million claims, and paid out $114 billion in unemployment benefits through either the federal Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program (PAU) or the California Unemployment Insurance (UI) program (Cal-EDD 2021). As means of comparison, during the Great Recession of 2010, only 3.8 million claims were processed. Cal-EDD (2021) claims that international and national crime syndicates attacked unemployment systems in every State, and that 9.7% of the payments it made were confirmed fraudulent. 95% of fraud targeted the PUA.

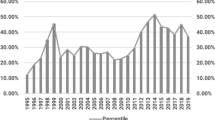

Los Angeles County was the one region in California most severely hit by the economic impacts of the pandemic. In 2020, 437,000 people lost their jobs in the County of Los Angeles. In June of 2020, 1 in 5 workers (20%) was out of work, compared to a 16.4% unemployment rate, statewide.

Tracking how the coronavirus crushed California’s workforce. (Source : Los Angeles Times (2021) Coronavirus unemployment: Tracking California’s fallout. (no page) https://www.latimes.com/projects/california-coronavirus-cases-tracking-outbreak/unemployment/)

Sectors such as hospitality (restaurants, tourism, bars, hotels), arts, entertainment and recreation, film and recording and retail were most deeply hit. As 2020 unemployment claims data indicated, those who lost their jobs in LA County tended to be extremely young (with half claimants being under the age of 35) with low-level educational attainment and over 40% were Latino or Hispanic. In light of projected revenue losses, the government also proceeded to massive layoffs. In California, 205,100 government jobs were lost between February 2020 and August 2020 (California Economic Development Department 2020).

Prior to the Pandemic, Los Angeles already struggled with staggering numbers of unsheltered individuals – living on the streets, in cars, in campers or in makeshift shelters or tents. 49,521 people were homeless in the Greater Los Angeles in 2019 (LAHSA 2020). The pandemic increased this number. The most recent homelessness count estimates the total homeless population at 54, 291Footnote 2. Also, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a few high-profile corruption cases have weakened public trust and demonstrated the fallibility of California’s largest city’s ethical safeguards. One scandal pertained to one of Los Angeles County’s main financial watchdog itself: the Los Angeles County’s Assessor’s office (LACAO). Three whistleblowers filed a lawsuit claiming that the County Assessor, his top managers and lawyers have allowed certain taxpayers to pay lower property taxes simply because they have ties to elected officials (Winton, 2019). As these high-profile cases have demonstrated, there were loopholes in the system that were exploited by malevolent individuals. Thus, legalist, compliance-based ethical programs can fail when presuming that employees will demonstrate judgment and integrity (Weaver & Treviño, 1999).

New pandemic-relief programs targeting small businesses also created new opportunities for fraud. Two individuals were convicted to six and seventeen years in federal prison, respectively, in relation to their lead of a fraud ring. They subtilized over $20 million in Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loan COVID-19 relief funds (COVID-relief SBA-loans; NBC 2021; Nouran, 2021). How was this possible? As our case study’s findings will demonstrate, lack of training, improper supervision practices, a risky organizational climate and the feeling of “injustice and helplessness” felt by frontline workers, were underestimated risk factors that hindered fraud detection and perhaps even contributed to higher levels of fraud and losses of pandemic-relief funds.

It is important to address the gap in research that pertains to the Los Angeles County’s institutional failures. As mentioned earlier, the Los Angeles County laid off employees massively in the wake of the pandemic due to projection of drastic cuts in tax revenues, and had to hire massively shortly thereafter to meet the demands of newly established programs. These programs were created out of an economic and political desire to withhold economic breakdown (recession) through heavily subsidizing citizens and businesses – through paycheck protection loan programs. Some individuals found ways to “work the system” and loot public resources: One ex-employee of California Employment Development Department alone having been able to obtain nearly $4.3 million (USD) in fraudulent covid-19 unemployment relief (ABC 7, 2021). As mentioned, a locally-based fraud ring was able to defraud as high as 20 million in forged applications to Small business loans program. Cal- EDD (2021) itself has released information indicating that “international and national crime Syndicates” were using stolen online identities and submitting important volumes of false claims. What has hindered local-level public institutions in their ability to ensure that federal and state COVID-relief transfers were properly allocated? How did local agencies adapt to the meet the demands stemming from the COVID public response and what are the lessons learned from prior mistakes?

Methodological approach

This presentation of results is inspired by Boisvert (2018)’s municipal corruption analysis, which allows for the identification or three dimensions of ethical risks: deviant behaviors, risk factors and mitigation/attenuation strategies. Boisvert (2018)’s ethical risk model provides a relevant theoretical “division” that favors both accuracy in diagnosis and a holistic, process-view of the risk-management system (or regime). This model has proven effective in the capturing of ethical risks faced by municipal-level agencies using similar qualitative methods.

Our case study (Yin, 2017; Flyvbjerg, 2011) followed a grounded-theory approach (Eisenhardt, 1989). No hypothesis was tested; the propositions emerged from an exploratory analysis of the case. The in-depth exploratory character of this analysis allowed for high conceptual validity (Yin, 2017). Our conceptualization of ethical drifts (See Table 2 and presented in the analysis section) stems essentially from our interviews, our data-mining and field notes. The triangulation method was used to allow multiple actors, data sources and data types to inform the case’s analysis.

Data collection

The data on which this case study relies includes primary interview data and secondary sources. The primary data was gathered between November 2021 and February 2022. Secondary sources include journalistic inquiries and credible news media reports (NBC4, ABC7, Los Angeles Times), Government reports, such as the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Public affairs press releases as well as qualitative interviews with one dozen civil servants from three major local agencies of Los Angeles County. The results hereby proposed stem mainly from the in-depth interviews with mid and lower-level workers and managers in COVID-19 benefits-managing entities. For purposes of confidentiality and results’ authenticity, the interviews were conducted with preservation of respondent’s confidentiality and anonymously. The names of employers also remained confidential. A semi-structured qualitative coding scheme was employed to facilitate data aggregation and analysis.

Data analysis

In an exploratory study of risks, whether ethical or of other forms of risks, the boundaries of the system are defined as “self-designed/ self-projected” (Kervern & Boulenger 2007; Kervern 1995); thus, the local-level agencies included in Table 2 are those mentioned by our respondents. The risk-governance system (risk network or risk regime) that was analyzed is comprised of our three local agencies’ internal and external stakeholders, the general public, as well as their accountability and reporting mechanisms, institutional and public watchdogs – and included political actors and the media. These self-projected boundaries are in fact “interfaces” between multiple levels. This analytical stance is important to promote analytical authenticity in qualitative case analyses of risks. There are dynamic factors that generate risk in the system which was analyzed. The Risk factors, mitigation strategies and deviant behaviors present in are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Findings’ summary – Dynamics of Ethical Risks LA County COVID-19 relief programs and funds. Caption: The Risk factors, mitigation strategies and deviant behaviors present in are listed in Table 2.

Many interrelated factors caused the failure of preventing the looting of state resources. Local public agencies struggled with communicational fragmentation, changing directives, financial uncertainty. Programs delivery was rushed and preventive measures were not properly in place. The Criminal justice system and investigative bodies such as the FBI had a limited power over the threat as their organizational structure and means were not adjusted until after the fraud crisis struck. The risk factors, coupled with weak and ineffective mitigation and prevention strategies laid fertile grounds for fraud, false applications and ultimately, the looting of public resources.

Main stakeholders in the risk regime

Any risk (governance) regime is comprised of a set of stakeholders (Hood et al., 2001). In our case, the main stakeholders are:

(1) Law enforcement institutions, such as Department of Justice, Local Law-Enforcement Agencies, LA County Assessor’s Office; Los Angeles’s Office of Anti-Corruption and Transparency, etc. are the ones managing and implementing core accountability and oversight mechanisms.

(2) The individual groups and cartels perpetrating fraud and looting public finances are those exploiting loopholes. They include those individuals that were never actually caught cheating the system.

(3) The political actors are broadly defined as the elected officials that define the policies and broad program orientations. They include, for the purpose of this analysis, the Executive Branch of the Federal government, U.S. policymakers (such as U.S. Congress and Senate members), the State Governor, elected representatives of the State of California, the Los Angeles’ mayor, and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. They are in charge of governing over a wide variety of programs, from rent-relief programs to nutritional, unemployment, health care, social and mental health, child and family services related programs.

(4) Local public agencies in this case analysis are the Departments and Divisions who are responsible for implementing these programs. They are federally or state-funded, and each have their specific authority/reporting structures (General managers, Advisory Boards, politically-appointed Commissioners, etc.). These local agencies find themselves oftentimes partnering with nonprofits or subcontractors, and represent the main interface with the public.

(5) Traditional and non-traditional news outlets (including social media) played an important role as they placed pressure upon policymakers to act. In this sense, the media helped disseminate information about risks, but also contributed to the fast-paced dynamics of risks and crisis within the governance network responsible for the proper allocation of COVID-19 relief funds.

Next, we apply the Boisvert framework to the analysis of this risk governance regime.

Risk factors

The first category of results pertains to the factors (human, political, economic, social, etc.) that shape the state agencies’ vulnerability to fraud and corruption. They comprise punctual contingencies as well as more permanent, historically inherited contextual characteristics. In this case, our results indicate that important shocks, reorganizations, demoralization and the urgency with which the relief funds needed to be encumbered created fertile grounds for fraud. The volatility of public financial environment, coupled with a rush in designing and implementing and distributing emergency-benefits programs – stemming from the State and Federal governments’ political desire to react swiftly to the crisis – created a certain loss of ethical safeguard capacity. In early stages of the pandemic, financial projections and budgetary updates at the local level predicted a steep decline in state revenue transfers and income tax. The stay-at-home orders affected many industries and therefore State, Federal and Local governments’ finances (Cain, 2020). Initial budgetary struggles from local governments resulted in massive layoffs, which then were followed by massive hires to meet the demands for COVID-relief-fund allocationFootnote 3. Competent, but hardly ever trained new hires were asked to perform their duties in crowded spaces, yet empty buildings. Supervisors were allowed to work remotely, but lower-level employees, such as eligibility workers, were not. This contributed to a sentiment of disenfranchisement, and conflicts in directives. As explained by a local agency’s employee: “When COVID 19 happened right at the beginning of my employment it was a very stressful time. I had no understanding of why actions were being taken or not being taken and it caused myself and other employees with no public background incredible stress and even fear” (Public Servant involved in Covid-19 relief fund distribution, December 2021). Changes in reporting mechanisms also occurred. Supervision, in some of COVID-19 relief program implementation hubs and centers, was deficient. Employees entrusted with eligibility determination were forced to accomplish tasks for which they were poorly trained, in the absence adequate support and supervision. One employee explains:

“There are times when things become a little more complex and when extra time is needed, as workers, we are questioned by our superiors as to why so much time is being spent on that case. (…) I have felt that I was being accused of wasting time. (…) The way in which we are being monitored can become demoralizing” (front-line bureaucrat working for an agency charged with distributing public COVID-19 relief funds- Interviewed in December 2021).

Indeed, supervision that is not comprehensive is detrimental to the workplace-climate and quality of work. Employees would seek “workarounds” - manners with which to meet quantitative performance metrics and not be the target of critiques and undue scrutiny. As an employee explains: “workers try to look for ways in which we can cheat the system” (front-line bureaucrat working for an agency charged with distributing public COVID-19 relief funds, December 2021) because of the pressure imposed by strict “inhuman” employee-oversight and surveillance methods. The system reportedly scrutinized employees’ break times, times on tasks and calls duration, notifying the supervisor when low or high thresholds were met. This created a feeling of disenfranchisement. Literature on social control advances that employees that are demoralized are at risk of disengaging with the mission of the agency, which can create larger scale integrity issues (Alter, 2003).

Our findings indicate that frontline workers who determine or have a great role to play in the determination of claimant’s eligibility to relief funds felt undervalued, and that their feedback regarding policy implementation issues was dismissed and did not reach policy-level spheres. Communication channels were not “bi-directional”, but only used to communicate directives from the top-down. These directives about eligibility, how to process claimants’ cases, and the like, were rapidly changing and often, found to be contradictory with earlier stipulations. Several respondents indicated that demands for help in implementing directives and for clarifications have been ignored. Problems of policy interpretation were often left unresolved, and employees felt left behind. What is more, employees felt like their own safety and security were disregarded by their superiors. As mentioned, teleworking was not allowed to lower-level employees, those interacting most with the public, through the phone or in-person. As a consequence of their crowded workplaces, it is believed that there was unnecessary COVID-19 exposure.

In short, risk factors such as a fast-pace news-reactive political environment trickled down to the agencies in charge of implementation of COVID-19 relief funds and direct monetary benefits. The overall administrative environment was characterized by heavy supervisory deficits, informational deficits and important lapses of quality assurance mechanisms, which fostered risks, policy loopholes and fraudulent behavior opportunities.

Forms of deviance

Three major forms of unethical behaviors were identified throughout the analysis of this case: internal, external and international. With regards to internal fraud, there is at least one case of an ex-employee of California Employment Development Department having been able to obtain nearly $4.3 million (USD) in fraudulent COVID-19 related unemployment relief (CARES Act funds; ABC 7, 2021). The ex-civil servant was able to use Social Security Numbers from out-of-state residents through her work as Tax Preparer. False claims have been processed and 197 debit cards were sent at various addresses, such as the residence or workplace of this ex- EDD’s employee’s friends and relatives. Only $600,000 were recovered by prosecuting authorities. Our analysis indicates that there is a strong possibility that other state employees – current or former having access to U.S. Citizens’ SSN lists and other personal information – used their insider’s knowledge to submit fraudulent claims. In other words, this case was probably not an isolated incident, and other State employees could very well have been involved in COVID-relief related fraud, or have been instrumental to some of the cases of fraud.

The second category of deviant practices is external: individuals and groups not associated with the agencies identified ways to exploit faults in state agencies’ oversight using forged documents. A highly mediatized example of this involved a “fraud ring” based in L.A. defrauded over $18 million USD in COVID-relief dedicated to helping small businesses (Paycheck Protection and Economic Injury Disaster Loan program funds). Several individuals in this case conspired using a complex scheme to loot public resources through 150 fraudulent small-business loans applications. They were caught partly because of the similarity of paycheck information that appeared on forged documents used to defraud the COVID-relief program. After being released on bail, three individuals went missing. They eventually were arrested in Montenegro, in 2022 (Daily News 2022).

Finally, a third form of deviance – international fraud – was also identified in documents published by the California Employment Development Department; that is, fraud attempts and fraudulent unemployment applications to California COVID-19 relief funds by international cartels (Cal- EDD, 2021). As of Sept., 31, 2021, nationwide, $872 billion were spent in COVID-relief to “assist American citizens with pandemic-related employment issues and challenges” and the portion of this amount believed to have been defrauded by international-based scammers could be as high as $200 billion (Office of the Inspector General 2021).

Hackers easily obtained information necessary to apply – and obtain – COVID-19 relief. The stratagem is quite simple; gather a list of real people, and turn to a database that charges a 2$ fee in cryptocurrency per individual for their date of birth and Social Security number. Most states required nothing more to process unemployment claims (Penzenstadler, 2020). Claimant could self-certify for their eligibility and apply to retroactive relief (Icaruci, 2021). “Organized crime has never had an opportunity where any American’s identity could be converted into $20,000, and it became their Super Bowl” according to FBI Deputy Assistant Director Jay Greenberg (cited by Dilanian Ramgopal & Atkins 2021, no page). Transnational organized crime groups based in Eastern Europe, West Africa and Asia benefited most from the policy failure. “In California, this is unquestionably the largest fraud against public agencies in our history”, according to Vern Pierson, president of the California District Attorneys Association (cited by Ramgopal et al., 2021). This situation placed public leaders of all levels under intense media pressure. On one hand, they were becoming aware their COVID-19 relief distribution systems were “under attack” by international scammers, but on the other hand, lawful claims were affected by the abrupt halting of services. For instance, many States’ EDD system’s months-long backlog led to public outcry. Because of international scammers flooding their systems, public agencies’ servers were crashing when already overwhelmed by the drastic increase in legitimate claims.

In California, 30 billion dollars are suspected to have been retrieved by International Scammers (Ramgopal et al., 2021). According to official accounts, the impact of this form of deviant behavior is believed to have been curbed by the reinforcing some of the initial loopholes in fraud-safeguard mechanisms. However, the sheer volume of applications processed by the State agencies at the height of the pandemic, as well as the lapses in the eligibility-verification mechanisms exacerbated by opportunities of online identity theft and created fertile grounds for the looting of public funds by internationally-based crime syndicates and online scammers.

Effectiveness of mitigation strategies

In September 2020, 100 million were transferred from the federal Department of Labor to States to combat fraud, but as much as 36 billion USD of fraudulent unemployment payments from U.S. Relief funds were already missing (Penzenstadler, 2020). Multiple factors, dynamically-intertwined fostered fraudulent behavior. Threats to accountability were numerous, especially given the multiplicity (and disconnectedness) of actors involved in preventing or prosecuting fraudulent activity. At a policy-level, the higher-level executives translate policy directives into actionable programs. They allocate funds and personnel to ensure proper delivery of those programs. However, resources needed for the proper execution of such directives may be misaligned with actual organizational capacity. In other words, the training, supervision, and quality-control mechanisms that must be in place to optimize work efforts from those upon which tasks are being bestowed were questionable in the wake of the COVID-19 relief programs and direct financial aid policies put in place. Training, the pillar of lawful and guidelines-compliant tasks from frontline workers, was particularly problematic. In one agency, what is described as a generalized lack of diligence from co-workers is viewed as hindering the agency’s capacity to efficiently make decisions and recommendations for funding eligible individual or businesses. As an employee explains, missing information is problematic when determining eligibility of an applicant.

“Although they always tell us to annotate a case and to include all information there are many workers that do not, making our job harder as then we need to play detectives and guess what may be the situation on the case. (…) there are those days where it seems that every case that I seem to get is a problematic case, as the applicant has not been processed properly” (local agency employee, lower-management level, interview of December 2021).

Mitigation strategies to COVID-19-related funds misappropriation which this analysis identified took two broad forms: prevention, on one hand, and deterrence and prosecution on the other hand. However, these strategies were not optimal for several risk factors and hindered their effectiveness. Coordination and adaptation capacity remain low for large bureaucracy, as exemplified in this interview excerpt: “[the agency for which I work] adapted too slowly. The administration is so used to red tape and policies, that when a disaster struck, and it was outside of that policy book, they had no idea what to do (…) And they left employees in the dark” (Frontline-level Civil servant employed by an institution that was charged with managing COVID-19 benefits). It would be important, especially in the wake of major disruptions and upheavals, that training and communication be emphasized rather than underestimated. A shared goal, and a common operating picture is critical to efficient crisis management (Comfort, Boin & Demchack 2010).

Discussion

Methodological implications

This project uses a case study approach (Van Thiel, 2014) inspired by pragmatism (Dewey, 1922, 1927) and the grounded theory (Eisenhardt, 1989). Qualitative research promotes flexible protocols, which create high validity within the case study’s findings. Our interviewees were public agency personnel members who possessed experience of relevant cases, processes, rules and systems in place. The goal of the analysis was to understand organizational dynamics affecting the risk regime. Respondents were asked about their experience with the COVID-19 response, downsizing, personnel re-affectation and relief programs eligibility. They were asked to discuss supervision tactics and ethical climates in local-level agencies. Grounded case study research typically produces highly actionable and transferable results, and in-situ knowledge about the detection and the prevention of corruption is best acquired through case study research (May & Perry, 2013).

Methodological limitations are inherent in any study. Case studies are not meant to generate generalizable data, but transferable finings (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). This analysis was qualitative in nature, and therefore only offers a descriptive view of the network analyzed. Moreover, for purposes of clarity and succinct presentation of the dynamism shaping risks in the stakeholder network, we selected the Boisvert (2018) typology and presented the results along three variables (dimensions): risk factors, deviant behaviors and attenuation strategies. Other typologies exist (see for instance Graycar 2015), but this one was selected for its sound conceptual clarity. The framework calls for an analysis of transactions between stakeholders which is useful to depict complex institutional dynamics. Dynamic-models (Shrivastava, 1992) offer interesting account of the complexity that create risks and crises. It is also worthy of mention that case-elements deemed peripheral to the research study were excluded. Only core results and findings were retained and presented in Table 2. Further analyses, of longitudinal or quantitative nature, or, focusing on single-institutions, (instead of an ensemble of agencies comprising a regulatory network) should complement this case analysis (Weber 1995).

Practical implications

Risk factors, potentially deviant behaviors and available and effective prevention mechanisms need to be well understood when creating – and, most importantly, maintaining over time – a proactive, resilient and inclusive ethical climate in public agencies. While corruption risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic have been the object of analysis in specific settings, such as health care systems (Teremetskyi et al., 2021), this analysis targets specifically local-level government. Thus, several lessons for local governments can be drawn from this analysis.

First, risk factors may be inevitable but this inevitability in no way should trigger complacency. In other words, political shifts, high demands for quick re-organization of resources, rushed implementation, etc. should not be an excuse not to double down on vigilance and proceed with a thorough analysis of the contextual conditions that will affect policy implementation. Crisis management expertise and readily available risk experts within local governments will alleviate some of the deficits herein identified. Secondly, forms of deviance will emerge as vulnerabilities appear. A commitment to understand the emerging risks associated with crisis-response will lead more effective identification of deviant behavior. Organizational capacity is of critical importance. In this regard, training case workers (and other eligibility-determining personnel) at identifying signs of deviance may represent a viable avenue to support prevention of misallocation of public funds, especially in times of crisis. Reactive attitudes are never as effective as proactive ones. Finally, when designing risk-mitigation strategies, proper emphasis must be placed upon relaying information effectively between workers, hierarchical levels and beyond departments. Strategic, data-driven leadership mindsets are needed for modern-era decision-making in local governments.

Some countries seem to have met the challenge of transparency and preventing misuse with greater effectiveness when designing a monitoring system for desired outcomes (Wendling et al., 2020). Transparency International warns against using “extra-budgetary mechanisms/ah-hoc budgetary mechanisms, because of democratic deficits and weakened oversight structures and suggested interesting long-tern solutions, including “the involvement of control and audit institutions in the design of programmes” (Oldfield, 2020, p. 17). The scale and speed of economic stimulus packages present a particular challenge for corruption prevention.

Conclusions

There are other risks – which have not been addressed here – which threaten process integrity when it comes to the allocation of public funds in terms of crisis. For instance, how much digital literacy is required from applicants? Is the profile of applicants diverse and reflective of minority/majority proportions? Are there fast-tracks that only the more privileged and technologically savvy (or insider-connected) may be aware of? Have benefits been distributed equally and have maximum amounts distributed fairly or has the processes of allocation been flawed due to implicit racial bias, gender bias, or otherwise uncontrolled human factors? Although these questions are beyond the scope of our analysis, they are legitimate and policymakers, program evaluation professionals, and society at large should continue to use caution with regards to evaluating implementation-related risks linked to emergency relief policies. The Devil is in the (implementation) details. Public administration scholars, and more specifically, the evaluation community must independently appraise the viability, inclusiveness and ethical character of proposed programs. All being said, public trust rests on diligent execution of policy orientations. As shifting, political agendas and priorities affect the public sector’s human resources, we must be cognizant of the risks posed to public funds’ integrity when employees themselves feel utilized, disenfranchised by “mechanistic control” and undervalued.

One lesson this research may offer to other settings and national contexts is the recurring issues of communication and coordination that bureaucracies under pressure almost inevitably experience. The importance of open, multi-directional communication, which enables effective multi-level, multi-partner’s coordination - must never be underestimated, especially in times of crisis. Some research found that public officials may deliberately slow down procurement process to allow more time for bribes (Lui, 1985). Information technology can increase corruption opportunities, rather than improve the capacity to curb it (Heeks, 1998). Further research could seek to improve our understanding of governmental and political cultures within institutions, federal transfer levels, government size/centralization and technology’s roles and impacts in deterring corruption.

Notes

“As of January 2, 2021, based on a conservative improper payment rate of 10%, we estimated that at least $39.2 billion in UI improper payments – including fraud – was at risk of not being detected and recovered. Estimates for the CARES Act and its related extensions range up to $873 billion; therefore, by program end, $87.3 billion in UI benefits could be paid improperly, with a significant portion attributable to fraud. The OIG’s initial pandemic audit and investigative work indicate that UI program improper payments, including fraudulent payments, will be higher than 10%. (Department of Labor/ OIG 2021 no page).

After negotiating reimbursement agreements with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the $150 million limited emergency “Project Roomkey” was launched by the California Governor’s office, securing up to 15,000 hotel rooms across the State (Hayden 2020). The goal was to shelter those most vulnerable to COVID-19, seniors, pregnant women and those with underlying conditions. 28, 000 individuals, about 17% of the State unsheltered population was temporary housed through this initiative, but only 5% of them found permanent housing when the project’s funding ended, on January 1st, 2021.

References

Alter, N. (2003). Régulation sociale et déficit de régulation » In: De Terssac, Gilbert. (Ed). La théorie de la régulation sociale de Jean-Daniel Reynaud Débats et prolongements pp. 77–88

Andreoli, N., & Lefkowitz, J. (2009). Individual and organizational antecedents of misconduct in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(3), 309–332

Boisvert, Y. (2018). L’analyse des risques éthiques: une recherche exploratoire dans le domaine de la gouvernance municipale. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique, 51(2), 305–334

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616

Busenberg, G. J. (1999). The evolution of vigilance: Disasters, sentinels and policy change. Environmental Politics, 8(4), 90–109

Cain, D. (2020). The Economic Impacts of Covid 19. Sizing-up the Covid-19 Fiscal Challenges; Public Governance for climate action International Institute of Administrative Sciences Annual Conference, December 17th 2020

Cal-EDD, (2021). Fraud by the numbers. Employment Development Department Info Sheet https://www.edd.ca.gov/unemployment/pdf/fraud-info-sheet.pdf

California State Controller (2022a). COVID-19 Relief and Assistance for Individuals and Families. https://www.sco.ca.gov/covid19ReliefAndAssitanceIF.html

California State Controller (2022b). COVID-19 Relief and Assistance for Small Business https://www.sco.ca.gov/covid19ReliefAndAssistanceSM.html

Campante, F. R., & Do, Q. A. (2014). Isolated capital cities, accountability, and corruption: Evidence from US states. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2456–2481

Cant, S. (2001). The Whistleblower. Information Management & Computer Security, 9(2/3), 137

Ceresola, R. G. (2019). The U.S. Government’s framing of corruption: A content analysis of public integrity section reports, 1978–2013. Crime Law and Social Change, 71(1), 47–65

Cho, Y. J., & Song, H. J. (2015). Determinants of whistleblowing within government agencies. Public Personnel Management, 44(4), 450–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026015603206

Coglianese, C. (2012). Regulatory Breakdown: The Crisis of Confidence in U.S. Regulation (Book collections on Project MUSE). Baltimore, Md.: Project MUSE

Comfort, L. K., Boin, A., & Demchak, C. C. (Eds.). (2010). Designing resilience: Preparing for extreme events. University of Pittsburgh Press

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications

Daily News (2020). LA County approves deep-cut budget plan, cutting thousands of positions. June 25, 2020. https://www.dailynews.com/2020/06/25/la-county-could-eliminate-3200-positions-and-lay-off-655-as-coronavirus-batters-budget/

Daily News (2022). February 23, 2022. 3 fugitives convicted in Encino-based $18 million coronavirus relief scam arrested in Montenegro https://www.dailynews.com/2022/02/23/3-fugitives-convicted-in-encino-based-18-million-coronavirus-relief-scam-arrested-in-montenegro/

Davis, M. (2012). Whistleblowing. Encyclopedia of Applied Ethics (Second Edition) pp. 531–538

Department of Labor / OIG (2021). DOL-OIG:Oversight of The Unemployment Insurance Program. https://oig.dol.gov/doloiguioversightwork.htm

Dewey, J. (1922). An analysis of reflective thought.The Journal of Philosophy,29–38

Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems: An essay in political inquiry

Dilanian, K. K., Ramgopal, & Atkins, C. (2021). Easy money’: How international scam artists pulled off an epic theft of Covid benefits August 15, 2021. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/easy-money-how-international-scam-artists-pulled-epic-theft-covid-n1276789

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review, 14(4), 532–550

Escaleras, M., Anbarci, N., & Register, C. A. (2006). Public sector corruption and natural disasters: A potentially deadly interaction (No. 06005)

Escaleras, M., Anbarci, N., & Register, C. A. (2007). Public sector corruption and major earthquakes: a potentially deadly interaction. Public Choice, 132(1–2), 209–230

Federal Bureau of Investigations (2016, May 3). News. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/public-corruption/news

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002). Decentralization and corruption: Evidence from US federal transfer programs. Public Choice, 113(1–2), 25–35

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case Study. In N. M. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (4th ed., pp. 301–316). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Freudenburg, W. R. (1993). Risk and recreancy: Weber, the division of labor, and the rationality of risk perceptions. Social forces, 71(4), 909–932

Freudenburg, W. R., & Gramling, R. (2012). Blowout in the Gulf: The BP oil spill disaster and the future of energy in America. MIT Press

Glaeser, E. L., & Saks, R. E. (2006). Corruption in America. Journal of public Economics, 90(6–7), 1053–1072

Gnankob, R. I., Ansong, A., & Issau, K. (2022). Servant leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour: the role of public service motivation and length of time spent with the leader.International Journal of Public Sector Management

Graycar, A. (2015). Corruption: Classification and analysis. Policy and Society, 34(2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.04.001

Green, P. (2005). Disaster by design: corruption, construction and catastrophe. British Journal of Criminology, 45(4), 528–546

Hayden, N. (2020). Project Roomkey funding ends soon. Over 11,000 Californians could become homeless, again. https://www.desertsun.com/in-depth/news/health/2020/10/30/over-11-000-californians-could-become-homeless-again/5875241002/

Heeks, R. (1998). Information technology and public sector corruption. Information systems for public sector management working paper, (4)

Holtzhausen, N. (2012). Variables influencing the outcomes of the whistle blowing process in South Africa. Administratio Publica, 20(4), 84–103. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/21007

Hood, C., Rothstein, H., & Baldwin, R. (2001). The government of risk: Understanding risk regulation regimes. OUP Oxford

Icaruci, G. (2021). More than $87 billion in federal benefits siphoned from unemployment system, says Labor Department. CNBC. Sept. 21 2021: www.cnbc.com/2021/12/02/over-87-billion-in-federal-benefits-siphoned-from-unemployment-system.html

Kervern, G. Y., & et Boulenger (2007). Cindyniques, concepts et mode d’emploi. Paris: Economica

Kervern, G. Y. (1995). Éléments fondamentaux des cindyniques. Paris: Economica

Kumara, A. S., & Handapangoda, W. S. (2014). Political environment a ground for public sector corruption? Evidence from a cross-country analysis (No. 54721). Germany: University Library of Munich

LAHSA (2020). The Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count. Online: https://www.lahsa.org

Lipman, F. D., & Lipman, F. D. (2012). Whistleblowers: Incentives, disincentives, and protection strategies (Wiley corporate F & A). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons

Liu, C., & Mikesell, J. L. (2014). The impact of public officials’ corruption on the size and allocation of U.S. state spending. Public Administration Review, 74(3), 346–359

Los Angeles County / Budget (2021). : LA County’s 2021-22 $36.2 Billion Recommended Budget Unveiled Online: https://lacounty.gov/budget/

Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office. (n.d.). Goals and Initiatives. Online: https://da.lacounty.gov/about/goals-and-initiatives

Lui, F. T. (1985). An equilibrium queuing model of bribery. Journal of political economy, 93(4), 760–781

May, T., & Perry, B. (2013). Reflexivity and the Practice of Qualitative Research. In Flick, U. (Ed). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, 109–122

NBC (2021). Couple Accused of Cutting Off Trackers and Fleeing in $18 Million Fraud Case Sentenced Despite Court No-Show. https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/coronavirus/encino-couple-covid-fraud-fbi-on-the-run/2760860/

Nouran, S. (2021). Fugitive Tarzana couple convicted in major COVID relief fraud scheme is sentenced as search for them continues https://ktla.com/news/local-news/fugitive-tarzana-couple-sentenced-in-major-covid-relief-fraud-scheme-is-sentenced-as-search-for-them-continues/

Oldfield, J. (2020). Literature review on anti-corruption safeguards for economic stimulus packages. Transparency International

Office of the Inspector General (2021). Semiannual report to Congress, U.S. Department of Labor https://www.oig.dol.gov/public/semiannuals/86.pdf

Penzenstadler (2020). How scammers siphoned $36B in fraudulent unemployment payments from US.USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/investigations/2020/12/30/unemployment-fraud-how-international-scammers-took-36-b-us/3960263001/

Ramgopal, K. A., Blankstein, & Winter, T. (2021). How billions in pandemic aid was swindled by con artists and crime syndicates Feb, 13 2021 NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/how-billions-pandemic-aid-was-swindled-con-artists-crime-syndicates-n1257766

Roosevelt, M. (2020). Despite gradual reopening, California’s unemployment rate remains stagnant Los Angeles Times. June 19, 2020. https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-06-19/coronavirus-unemployment-california-jobs-may

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1975). The economics of corruption. Journal of public economics, 4(2), 187–203

Shrivastava, P. (1992). Bhopal: Anatomy of a Crisis (2nd ed.). London: Paul Chapman Publishing

Stacey, R., & Griffin, D. (Eds.). (2006). Complexity and the Experience of Managing in Public Sector Organizations. London: Routledge

State of California: Employment Development Department (2021). Current Employment Statistics (CES) https://data.edd.ca.gov/Industry-Information-/Current-Employment-Statistics-CES-/r4zm-kdcg/data

Teremetskyi, V., Duliba, Y., Kroitor, V., Korchak, N., & Makarenko, O. (2021). Corruption and strengthening anti-corruption efforts in healthcare during the pandemic of Covid-19. Medico-Legal Journal, 89(1), 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0025817220971925

Transparent California (2018). California’s Largest Public Pay and Pension Database. https://transparentcalifornia.com

U.S. Census Bureau (2022). QuickFacts, California https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/CA

Ulmer, J. T. (2000). Commitment, Deviance and Social Control. The Sociological Quarterly, 41(3), 315–336

Van Niekerk, T., & Dalton-Brits, E. (2016). Mechanisms to strengthen accountability and oversight within municipalities, with specific reference to the Municipal Public Account Committee and the Audit Committee of the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(3), 117–128. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/58213

Van Niekerk, T., Valiquette L’Heureux, A., & N. Holtzhausen (2022) State Capture in South Africa and Canada: A Comparative Analysis, Public Integrity, https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2046968

Van Thiel, S. (2014). The Case Study. In Research methods in public administration and public management: An introduction. Routledge. Chapter 8. (pp. 86–101)

Veetikazhi, R., Kamalanabhan, T. J., Malhotra, P., Arora, R., & Mueller, A. (2021). Unethical employee behaviour: a review and typology.The International Journal of Human Resource Management,1–43

Villoria, M., Van Ryzin, G. G., & Lavena, C. F. (2013). Social and political consequences of administrative corruption: A study of public perceptions in Spain. Public Administration Review, 73(1), 85–94

WDACS (2020). PATHWAYS FOR ECONOMIC RESILIENCY: Los Angeles County 2021–2026 DECEMBER 2020. https://wdacs.lacounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Pathways-for-Economic-Resiliency-Condensed-Report-FINAL.pdf

Weaver, G., & Treviño, L. (1999). Compliance and Values Oriented Ethics Programs: Influences on Employees’ Attitudes and Behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly, 9(2), 315–335

Weber, J. (1995). Influences upon organizational ethical subclimates: A multi-departmental analysis of a single firm. Organization Science, 65, 509–523

Wendling, C., Alonso, V., Saxena, S., Tang, V., & Verdugo, C. (2020). Keeping the receipts: Transparency, accountability, and legitimacy in emergency responses. IMF Special Series on Fiscal Policies to Respond to COVID-19, Fiscal Affairs Department, Washington DC

Winton, R. (2019). ‘Connected’ taxpayers got breaks with L.A. County assessor’s office, whistleblowers allege. October 8, 2019 Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-10-08/connected-taxpayers-got-breaks-with-l-a-county-assessors-office-whistleblowers-allege

Yamamura, E. (2014). Impact of natural disaster on public sector corruption. Public Choice, 161(3–4), 385–405

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage publications

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Shauna Clark for her thoughtful suggestions and editing of this manuscript.

Funding

(None/Not applicable)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Yes.

Informed consent

Yes – Research participants were read a consent form (Informed consent and voluntary participation; Consent forms signature waver granted by IRB).

Ethical approval

IRB (CSUN) approved this study’s Protocol on 10/15/2021 (IRB-FY22-6) (Expiration/ Renewal date: 10/15/2022.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valiquette L’Heureux, A. The Case Study of Los Angeles City & County Fraud, Embezzlement and Corruption Safeguards during times of pandemic. Public Organiz Rev 22, 593–610 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00641-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00641-w