Abstract

Understanding and managing hospital Organizational Readiness to Change is a key topic with strong practical implications on society worldwide. This study provides, through a scoping literature review, a framework aimed at creating a road map for hospital managers who are implementing strategic processes of change. Ideally, the framework should act as a check-list to proactively detect those items that are likely to impede successful change. 146 items were identified and clustered into 9 domains. Finally, although built for the hospital setting, similar research approaches could be highly effective also in other large, public organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although topics such as organizational readiness to change (ORC), organizational resilience and change management are all widely addressed in organizational studies in the private/industrial sector (Grimolizzi-Jensen, 2018), they are, by now, of the utmost importance for large, public organizations too (Sawitri, 2018). In general, managerial revolutions such as the one of New Public Management (Nunes & Ferreira, 2019) have gradually clarified that many challenges typically faced in the private sector are by now just as relevant in the public one. For example, ORC is a highly relevant aspect of public organizations, frequently required to implement managerial tools borrowed from the private industry so to pursue objectives related to both quality and efficiency simultaneously (Veillard et al., 2005). ORC is a construct that describes an organization’s capability of implementing a transformation, whether planned or sudden.

A clear example of its relevance can be found in hospitals. These are (frequently public) large and complex organizations which are required to adapt to rapidly changing environments. Although their trends of change are widely studied (Gabutti & Cicchetti, 2020), there exists high variability in their ability of responding to common challenges. For example, this has become evident with the Covid-19 pandemic which has obliged hospitals to face unprecedent and completely unknown scenarios and to rely nearly exclusively on their managerial asset to adapt quickly to an evolving environment (Gibbons et al., 2021).

Therefore, understanding and managing hospital ORC is a key topic with strong practical implications on society worldwide. Hospital ORC has been studied in the past (Vaishnavi et al., 2019). Nevertheless, studies mostly address specific features of hospital ORC and mostly fail in providing a comprehensive framework able to guide managers in the overall assessment and improvement of ORC. Indeed, taking complex decisions when such a comprehensive framework is not available is risky. It is difficult to foresee the interconnected effects a decision implies. Moreover, there may exist numerous organizational and contextual features that could hinder the implementation and success of such decision. In other terms, strategies may fail due to the high number of barriers that impede a concrete process of organizational change (Sicakyuz & Yuregit, 2020).

In this scenario, it is important to provide a concrete framework to classify (and manage) the various dimensions of hospital ORC. This framework is aimed at providing a road map to hospital managers who are implementing strategic processes of change. Ideally, the framework should act as a check-list to proactively detect those items that are likely to impede successful change.

Background

Healthcare organizations worldwide are undergoing deep transformations to respond to multiple challenges (Daniel et al., 2013). Terms such as "patient-centred care," "clinical pathways," "integrated care” (Daniel et al., 2013; Gabutti & Cicchetti, 2020) are increasingly used in the daily lexicon of those who manage health organizations (Rathert et al., 2013). This means that health care organizations, and hospitals in particular, are facing deep organizational innovations with, for example, transitions from vertical to horizontal organizational models and from managerial approaches based on individual (at the unit level) accountability to assets based on joint accountability (Carini et al., 2020).

In this evolving scenario, coercive isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) is frequently at the basis of hospital compliance with the provisions of national or supranational institutions. Hospitals are obliged to change so to adapt to compulsory indications coming from outside. However, hospitals can also play a proactive role in implementing organizational change (Ribera et al., 2016), giving rise to forms of so-called mimetic isomorphism (Mascia et al., 2014). In this case, they freely choose to implement change and imitate successful strategies observed in similar organizations. Whatever the nature and motives behind organizational change, this must be supported by an adequate contextual and managerial scenario if doomed to succeed.

Implementing organizational change is an unquestionably challenging process due to the many factors that may hinder it. Managers should be fully aware of the organizational dimensions that may affect any transformation process. It is essential to know how to evaluate ORC so to avoid "decoupling phenomena," which imply a discrepancy between theoretical strategic decisions and concrete operational change (Mascia et al., 2014). ORC is indeed considered a critical foundation to implement complex change in healthcare settings successfully (Weiner, 2009). It has been reported that failure to establish adequate readiness accounts for one-half of all ineffective, large-scale organizational change efforts (Weiner, 2009).

Several authors have faced this issue and detected some items which may affect ORC in healthcare organizations. However, most of the published literature is focused on specific aspects of ORC, which cannot be directly translated into holistic assessments of this construct. A conceptual framework to understand factors influencing ORC was provided in a landmark study describing four key constructs that constitute ORC: "Individual psychological, Individual structural, Organizational psychological and Organizational structural (Holt et al., 2010a). In other words, factors influencing ORG may either be ascribable to a physical person or to the organization as a whole and may either belong to hard (structural) or soft (psychological) dimensions. Nevertheless, though highly relevant, this study does not provide guidance on the concrete functional dimensions that managers may use to effectively drive change in a hospital.

This study categorizes evidence from extant literature so to identify a complete range of domains able to affect ORC in hospitals, specifying for each their main items and providing an exhaustive framework for managers called to implement change through them.

Methods

To identify the domains and items that can affect ORC in hospitals, we performed a scoping review of the literature published over the last ten years. The Web of Knowledge database was searched with the following search string:

-

TS = (readiness) OR TS = (willingness) OR TS = (inclination) OR TS = (eagerness) OR TS = (promptness) OR TS = (preparedness)

-

AND TS = (chang*) OR TS = (reorganization*) OR TS = (transformation*) OR TS = (metamorphos*) OR TS = (restructur*) OR TS = (remodelling)

-

AND TS = (health*) OR TS = (medic*) OR TS = (hospital*)

-

Indexes = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan = 2010–2020

-

Refined by: WEB OF SCIENCE CATEGORIES: (MANAGEMENT OR OPERATIONS RESEARCH MANAGEMENT SCIENCE).

Three independent researchers analysed the articles retrieved to assess their relevance to the study's purposes. Articles were included in the study if at least two out of three researchers classified them as potentially relevant. The articles included in the study were analysed to identify a set of domains able to affect hospital ORC as well as their specific items. For each relevant article, all the items detected were clustered into the emerging domains.

Results

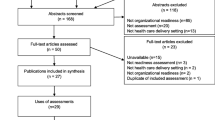

The search identified 2068 articles. After eliminating 347 duplicate records, three independent researchers performed an analysis of the paper's title and abstract. 61 articles were considered potentially relevant. After an in-depth analysis of full-texts, 52 articles were selected (Fig. 1). 146 items were identified and clustered into 9 domains: Cultural (CULT), Economic and Financial (ECON), External Factors (EXT), Human Resources Management (HRM), Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), Leadership (LEAD), Managerial Accounting (MA), Organizational Structural Factors (ORG). Only one item was not logically attributable to these domains and was therefore included in the domain "Other" (Annex 1). This final domain was then dropped in the analysis due to its scarce relevance and consistency with the overall framework of the study. The individual items were then carefully analysed to assess analogies, with the aim of grouping them into homogeneous super-items. The grouping process was achieved with a Delphi iteration, and the initial 146 items were reduced to 48 super-items, as detailed in Table 1. In this way, for each domain it has been possible to extract the key features and contents that characterize it.

The External environmental domain refers to the main trends in the healthcare system (and in the environment in general) in which the hospital operates. New approaches in the provision of care such as patient-centred care, transitional care models and continuity of care to contrast fragmentation, are all examples of super-items within this domain. Furthermore, the set of institutional, normative and reimbursement rules represent other relevant super-items in this area.

The Organizational/structural domain concerns the “hard” dimensions of the hospital. Their organizational charts (whether vertical, horizontal, or matrix-formed) and their overall coherence with their strategic objectives are among the main super-items of this domain. In particular, the presence of organizational units that are adequate in guaranteeing continuity of care and in providing forms of liaison with primary healthcare settings are likely to enable many of the changes hospitals implementing.

The Managerial accounting domain includes super- items concerning the presence of tools aimed at detecting and monitoring relevant indicators which can drive management towards an effective implementation of the organizational strategy. These must be able to support a clear understanding of a hospital’s performance, to be intended in its various acceptations (e.g., clinical, financial, logistic) and both at a macro, meso, and micro level. This will provide a timely access to performance indicators that can support swift decision-making.

The Information and communication technology domain refers to the set of ICT tools which can support a timely and exhaustive access to different types of information, including those on clinical aspects, processes, administrative data. The super-item of a shared (both within the hospital and across different organizations) ICT platform and of a common language in the treatment of data, assumes primary importance in the hospital’s ability of being responsive to change.

The Economic and financial resources domain has to do with both the overall availability of resources as well as with the coherence of their assignment to organizational units (e.g., through budgeting). Such coherence should be interpreted in the light of the hospital’s main objectives.

The domain concerning Human resource management covers the overall set of HRM tools adopted (and properly implemented) in the hospital. Main relevance is assigned to strategic HRM initiatives such as, for example, activity planning and competency modeling. Furthermore, the coherence of career pathways with the main trends of transformation of hospitals is key in the assessment of the sustainability of the latter.

The Leadership domain refers to the general leadership style within the hospital. Although possibly subjective at the individual level, leadership styles can indeed vary across organizations. For example, organizations that encourage shared decision-making and bottom-up communication flows are likely to better respond to timely requests of change that imply an active participation of staff at different levels.

Finally, the Cultural domain concerns the general “atmosphere” felt by staff, with a great difference emerging between organizations that adopt a coercive and corrective approach as opposed to those that appear supportive and encouraging. The extent to which values such as trust, respect, transparency and honesty are pursued, is key in detecting the willingness of staff to implement change.

Discussion

Organizational readiness to change is a widely explored construct in numerous contexts, including in the healthcare sector. It has been assessed from multiple perspectives, but these are usually limited to one or a few dimensions that may affect it. Comprehensive assessments of organizations’ domains to be managed jointly to implement change effectively, seem to be lacking. This literature review attempts to cover this gap and provides guidance to assess overall ORC in hospitals.

This work's pragmatic output provides a basis to build ORC conceptual mapping across different organizational units and areas. For example, some hospitals may be well suited in their HRM asset and lead people towards the intended change successfully. However, they may be anchored to obsolete structural models that slow down the change process. Following this example, if the current organizational chart is not coherent with the new responsibilities professionals are likely to have, the overall result will be disappointing. Again, if an organization is lacking an appropriate managerial accounting system able to monitor the relevant data to implement change, this may not occur even though leadership, for example, is highly effective.

If relevant in general, such an approach appears crucial in the current scenario, greatly affected by the pandemic. Public health organizations may have an interest to assess their overall ORC in order to understand what has hindered or enabled their ability to react quickly to the crisis. Those hospitals that have shown more flexibility and have rapidly adapted to the changing environment have possibly structured a better response to the emergency. ORC is the essence of this intrinsic resilience.

More generally, developing a deep awareness of overall ORC will highly and positively affect organizations' capability of reaching their strategic objectives.

It is worth mentioning a few limits of this study. The main limitation may have to do with the criteria used to cluster items into domains. Given that there is no validated method to do this, researchers have relied on their knowledge of the various domain contents and meanings. Items were grouped accordingly. Nevertheless, whenever consensus was not reached by the first two researchers, the third intervened to mediate conflicts, and a complete consensus was then always reached.

A second limitation has to do with the decision of exploring all available literature in the field without distinguishing by type of hospital (e.g., based on its dimension, mission, location). Although this has been done to detect as much information as possible, there may exist relevant differences between organizations of different types. Future studies should focus on such differences and grasp possible distinctions among their relevant domains and super-items.

Conclusions

The results of this study provide a starting point to build guiding tools for managers when implementing relevant change within their hospital. Such tools could lead to easy-to-read dashboards, alerting them on the organizational dimensions that are more likely to hinder change in their specific context. This, in turn, would shed light on the problematic aspects they should correct with priority before incurring into unsuccessful, costly plans of change.

At its current stage, the framework provides guidance on the super-items to be assessed but not on the desirable, specific configurations of each. This means that the evaluation of the adequacy of each super-item is left to managers, who must assess them in the light of the specific change process they are willing to implement. Although some “general trends” in the specific configurations of super-items may emerge, these may at times be adequate in some scenarios and not in others. For example, although hospital organizational charts are more and more frequently based on horizontal units of responsibility as a response to the strong need of providing integrated care, a specific hospital may still find it convenient to rely on rather vertical organizational units. Future studies should further decline items, super-items, and domains so to relate them to typical strategies of change.

Finally, although built for the hospital setting, similar research approaches could be highly effective in other large, public organizations. Whether the domains at the basis of ORC in other organizations overlap completely or differ to some extent from those of hospitals, should be further explored.

References

Abrahamsen, C., Norgaard, B., & Draborg, E. (2017). Health care professionals’ readiness for an interprofessional orthogeriatric unit: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 26, 18–23.

Al-Hussami, M., Hamad, S., Darawad, M., & Maharmeh, M. (2017). The effects of leadership competencies and quality of work on the perceived readiness for organizational change among nurse managers. Leadership in Health Services (Bradford, England), 30(4), 443–456.

Al-Hussami, M., Hammad, S., & Alsoleihat, F. (2018). The influence of leadership behavior, organizational commitment, organizational support, subjective career success on organizational readiness for change in healthcare organizations. Leadership in Health Services, 31(4), 354–370.

Alharbi, M. F. (2018). An analysis of the Saudi health-care system’s readiness to change in the context of the Saudi National Health-care Plan in Vision 2030. International Journal of Health Sciences-Ijhs, 12(3), 83–87.

Amarantou, V., Kazakopoulou, S., Chatzoudes, D., & Chatzoglou, P. (2018). Resistance to change: An empirical investigation of its antecedents. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 31(2), 426–450.

Augustsson, H., Richter, A., Hasson, H., & Schwarz, U. V. (2017). The need for dual openness to change: A longitudinal study evaluating the impact of employees’ openness to organizational change content and process on intervention outcomes. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(3), 349–368.

Austin, T., Chreim, S., & Grudniewicz, A. (2020). Examining health care providers' and middle-level managers' readiness for change: a qualitative study. Bmc Health Services Research, 20(1).

Bakari, H., Hunjra, A. I., & Jaros, S. (2020). Commitment to Change Among Health Care Workers in Pakistan. Journal of Health Management.

Bastemeijer, C. M., Boosman, H., van Ewijk, H., Verweij, L. M., et al. (2019). Patient experiences: A systematic review of quality improvement interventions in a hospital setting. Patient-Related Outcome Measures, 10, 157–169.

Benzer, J. K., Charns, M. P., Hamdan, S., & Afable, M. (2017). The role of organizational structure in readiness for change: A conceptual integration. Health Services Management Research, 30(1), 34–46.

Bickerich, K., & Michel, A. (2016). Executive coaching during organizational change: The moderating role of autonomy and management support. Zeitschrift Fur Arbeits-Und Organisationspsychologie, 60(4), 212–226.

Billsten, J., Fridell, M., Holmberg, R., & Ivarsson, A. (2018). Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC) test used in the implementation of assessment instruments and treatment methods in a Swedish National study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 84, 9–16.

Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7, 37.

Carini, E., Gabutti, I., Frisicale, E. M., Di Pilla, A., et al. (2020). Assessing hospital performance indicators. What dimensions? Evidence from an umbrella review. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1038. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05879-y

Castaneda, S. F., Holscher, J., Mumman, M. K., Salgado, H., et al. (2012). Dimensions of community and organizational readiness for change. Progress in Community Health Partnerships-Research Education and Action, 6(2), 219–226.

Daniel, D. M., Wagner, E. H., Coleman, K., Schaefer, J. K., et al. (2013). Assessing progress toward becoming a patient-centered medical home: An assessment tool for practice transformation. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 1), 1879–1897. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12111

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Feiring, E., & Lie, A. E. (2018). Factors perceived to influence implementation of task shifting in highly specialised healthcare: A theory-based qualitative approach. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 899. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3719-0

Gabutti, I., & Cicchetti, A. (2020). Translating strategy into practice: A tool to understand organizational change in a Spanish university hospital. An in-depth analysis in Hospital Clinic. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 13(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2017.1336837

Gibbons, J. P., Forman, S., Keogh, P., Curtin, P., et al. (2021). Crisis change management during COVID-19 in the elective orthopaedic hospital: Easing the trauma burden of acute hospitals. Surgeon, 19(3), e59–e66.

Grimolizzi-Jensen, C. J. (2018). Organizational change: Effect of motivational interviewing on readiness to change*. Journal of Change Management, 18(1), 54–69.

Han, L., Liu, J., Evans, R., Song, Y., et al. (2020). Factors Influencing the Adoption of Health Information Standards in Health Care Organizations: A Systematic Review Based on Best Fit Framework Synthesis. Jmir Medical Informatics, 8(5).

Hauck, S., Winsett, R. P., & Kuric, J. (2013). Leadership facilitation strategies to establish evidence-based practice in an acute care hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(3), 664–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06053.x

Holt, D. T., Helfrich, C. D., Hall, C. G., & Weiner, B. J. (2010a). Are you ready? How health professionals can comprehensively conceptualize readiness for change. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(Suppl 1), 50–55.

Holt, D. T., Helfrich, C. D., Hall, C. G., & Weiner, B. J. (2010b). Are you ready? How health professionals can comprehensively conceptualize readiness for change. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25, 50–55.

Jackson, G. L., Rournie, C. L., Rakley, S. M., Kravetz, J. D., et al. (2017). Linkage between theory-based measurement of organizational readiness for change and lessons learned conducting quality improvement-focused research. Learning Health Systems, 1(2).

Jakobsen, M. D., Aust, B., Dyreborg, J., Kines, P., et al. (2016). Participatory organizational intervention for improved use of assistive devices for patient transfer: Study protocol for a single-blinded cluster randomized controlled trial. Bmc Musculoskeletal Disorders, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1339-6

Jakobsen, M. D., Clausen, T., & Andersen, L. L. (2020). Can a participatory organizational intervention improve social capital and organizational readiness to change? Cluster randomized controlled trial at five Danish hospitals. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(10), 2685–2695.

Kabukye, J. K., de Keizer, N., & Cornet, R. (2020). Assessment of organizational readiness to implement an electronic health record system in a low-resource settings cancer hospital: A cross-sectional survey. Plos One, 15(6).

Kampstra, N. A., Zipfel, N., van der Nat, P. B., Westert, G. P., et al. (2018). Health outcomes measurement and organizational readiness support quality improvement: a systematic review. Bmc Health Services Research, 18.

Karalis, E., & Barbery, G. (2018). The common barriers and facilitators for a healthcare organization becoming a high reliability organization. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 13(3), 13.

Kelly, P., Hegarty, J., Barry, J., Dyer, K. R., et al. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between staff perceptions of organizational readiness to change and the process of innovation adoption in substance misuse treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 80, 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.06.001

Lim, D., Schoo, A., Lawn, S., & Litt, J. (2019). Embedding and sustaining motivational interviewing in clinical environments: A concurrent iterative mixed methods study. Bmc Medical Education, 19,. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1606-y

Lundmark, R., Nielsen, K., Hasson, H., Schwarz, U. V., et al. (2020). No leader is an island: Contextual antecedents to line managers’ constructive and destructive leadership during an organizational intervention. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 13(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijwhm-05-2019-0065

Magdzinski, A., Marte, A., Boitor, M., Raboy-Thaw, J., et al. (2018). Transition to a newly constructed single patient room adult intensive care unit - Clinicians’ preparation and work experience. Journal of Critical Care, 48, 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.09.023

Mascia, D., Morandi, F., & Cicchetti, A. (2014). Looking good or doing better? Patterns of decoupling in the implementation of clinical directorates. Health Care Management Review, 39(2), 111–123.

Masood, M., & Afsar, B. (2017). Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior among nursing staff. Nursing Inquiry, 24(4).

Mazur, L., Stokes, S. B., & McCreery, J. (2019). Lean-thinking: Implementation and measurement in healthcare settings. Engineering Management Journal, 31(3), 193–206.

Miake-Lye, I. M., Delevan, D. M., Ganz, D. A., Mittman, B. S., et al. (2020). Unpacking organizational readiness for change: an updated systematic review and content analysis of assessments. Bmc Health Services Research, 20(1).

Minyard, K., Smith, T. A., Turner, R., Milstein, B., et al. (2018). Community and programmatic factors influencing effective use of system dynamic models. System Dynamics Review, 34(1–2), 154–171.

Morin, A. J. S., Meyer, J. P., Belanger, E., Boudrias, J. S., et al. (2016). Longitudinal associations between employees’ beliefs about the quality of the change management process, affective commitment to change and psychological empowerment. Human Relations, 69(3), 839–867.

Mrayyan, M. T. (2020). Nurses’ views of organizational readiness for change. Nursing Forum, 55(2), 83–91.

Nelson-Brantley, H. V., & Ford, D. J. (2017). Leading change: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(4), 834–846.

Nunes, A., & Ferreira, D. (2019). The health care reform in Portugal: Outcomes from both the new public management and the economic crisis. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(1), 196–215.

Nuno-Solinis, R. (2018). Are healthcare organizations ready for change? Comment on “Development and Content Validation of a Transcultural Instrument to Assess Organizational Readiness for Knowledge Translation in Healthcare Organizations: The OR4KT.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7(12), 1158–1160.

Oygarden, O., & Mikkelsen, A. (2020). Readiness for change and good translations. Journal of Change Management, 20(3), 220–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2020.1720775

Pfortmiller, D. T., Mustain, J. M., Lowry, L. W., & Wilhoit, K. W. (2011). Preparing for organizational change project: SAFETYfirst. Cin-Computers Informatics Nursing, 29(4), 230–236.

Proctor, E., Ramsey, A. T., Brown, M. T., Malone, S., et al. (2019). Training in Implementation Practice Leadership (TRIPLE): evaluation of a novel practice change strategy in behavioral health organizations. Implementation Science, 14.

Puchalski Ritchie, L. M., & Straus, S. E. (2019). Assessing organizational readiness for change comment on “Development and Content Validation of a Transcultural Instrument to Assess Organizational Readiness for Knowledge Translation in Healthcare Organizations: The OR4KT.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 8(1), 55–57.

Randall, C. L., Hort, K., Huebner, C. E., Mallott, E., et al. (2020). Organizational readiness to implement system changes in an Alaskan tribal dental care organization. JDR Clinical & Translational Research, 5(2), 156–165.

Rathert, C., Wyrwich, M. D., & Boren, S. A. (2013). Patient-centered care and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review, 70(4), 351–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774

Ribera J, A. G., Rosenmoeller M., Borras P. (2016). Hospital of the future: a new role for leading hospitals in Europe. In U. o. N. E. IESE Business School.

Sawitri R., W. S. (2018). Readiness to Change in the Public Sector. International Journal of Business and Society, 19(No.1), 259–267.

Schultz, T., Shoobridge, J., Harvey, G., Carter, L., et al. (2019). Building capacity for change: Evaluation of an organisation-wide leadership development program. Australian Health Review, 43(3), 335–344.

Sicakyuz, C., & Yuregit, O. H. (2020). Exploring resistance factors on the usage of hospital information systems from the perspective of the Markus’s Model and the Technology Acceptance Model. Journal of Entrepreneurship Management and Innovation, 16(2), 93–129.

Sola, G. J. I., Badia, J. G. I., Hito, P. D., Osaba, M. A. C., et al. (2016). Self-perception of leadership styles and behaviour in primary health care. Bmc Health Services Research, 16.

Sopow, E. (2020). Aligning workplace wellness with global change: an integrated model. Journal of Organizational Change Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-11-2019-0334

Spitzer-Shohat, S., & Chin, M. H. (2019). The “Waze” of inequity reduction frameworks for organizations: A scoping review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(4), 604–617.

Tummers, L., Kruyen, P. M., Vijverberg, D. M., & Voesenek, T. J. (2015). Connecting HRM and change management: The importance of proactivity and vitality. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(4), 627–640.

Vaishnavi, V., & Suresh, M. (2020). Modelling of readiness factors for the implementation of Lean Six Sigma in healthcare organizations. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 11(4), 597–633.

Vaishnavi, V., Suresh, M., & Dutta, P. (2019). A study on the influence of factors associated with organizational readiness for change in healthcare organizations using TISM. Benchmarking-an International Journal, 26(4), 1290–1313.

Vaughn, V. M., Saint, S., Krein, S. L., Forman, J. H., et al. (2019). Characteristics of healthcare organisations struggling to improve quality: Results from a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Quality and Safety, 28(1), 74–84.

Veillard, J., Champagne, F., Klazinga, N., Kazandjian, V., et al. (2005). A performance assessment framework for hospitals: The WHO regional office for Europe PATH project. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 17(6), 487–496.

von Treuer, K., Karantzas, G., McCabe, M., Mellor, D., et al. (2018). Organizational factors associated with readiness for change in residential aged care settings. Bmc Health Services Research, 18.

Weiner, B. J. (2009). A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 4, 67.

Willis, C. D., Saul, J., Bevan, H., Scheirer, M. A., et al. (2016). Sustaining organizational culture change in health systems. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 30(1), 2–30.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

None (not required due to the nature of the research).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Annex 1. Items of hospital organizational readiness to change

Annex 1. Items of hospital organizational readiness to change

Authors | Item | Domain |

|---|---|---|

(Abrahamsen et al., 2017) | Interprofessional collaboration model | CULT |

(Amarantou et al., 2018) | Resistance to change is influenced by four main factors (employee-management relationship, personality traits, employee participation in the decision-making process, and job security); disposition towards change, anticipated impact of change and attitude towards change mediate the impact of various personal and behavioral characteristics on RtC | CULT |

(Augustsson et al., 2017) | individual- and group-level openness to organizational change | CULT |

(Austin et al., 2020) | individual readiness factors, central role of middle manager, how frontline providers and middle managers experienced six readiness factors: discrepancy, appropriateness, valence, efficacy, fairness and trust in management | CULT |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | continuous assessment of patient experiences | CULT |

(Billsten et al., 2018) | motivational readiness, institutional resources, staff attributes, and organizational climate | CULT |

(Castaneda et al., 2012) | community and organizational climate that facilitates change | CULT |

(Castaneda et al., 2012) | (1) community and organizational climate that facilitates change, (2) attitudes and current efforts toward prevention, (3) commitment to change, and (4) capacity to implement change | CULT |

(Feiring & Lie, 2018) | Three factors were related to capability, including (1) knowledge and acceptability of task shifting rationale; (2) dynamic role boundaries; and (3) technical skills to perform biopsies and aspirations. Five factors were related to motivation, including (4) beliefs about task shifting consequences, such as efficiency, quality and patient satisfaction; (5) beliefs about capabilities, such as technical, communicative and emotional skills; (6) job satisfaction and esteem; (7) organisational culture, such as team optimism; and (8) emotions, such as fear of informal nurse hierarchy and envy. The last two factors were related to opportunity, including (9) project planning and leadership, and voluntariness; and (10) patient preferences | CULT |

(Han et al., 2020) | The organization dimension included organizational scale, organizational culture, staff resistance to change, staff training, top management support, and organizational readiness | CULT |

(Jakobsen et al., 2016) | Implementing participatory interventions at the workplace may be a cost-effective strategy as they provide additional benefits, e.g., increased social capital and improved organizational readiness for change, that exceed the primary outcome of the intervention | CULT |

(Kabukye et al., 2020) | organizational flexibility and collective self-efficacy | CULT |

(Karalis & Barbery, 2018) | staff education, and analysing the safety events and sharing the knowledge | CULT |

(Kelly, et al., 2017) | relationship between staff perceptions of ORC and the process of innovation adoption: exposure, adoption, implementation and integration into practice | CULT |

(Kelly et al., 2017) | organizational functioning, better program resources and specific staff attributes, staff workloads, good organizational climate | CULT |

(Mrayyan, 2020) | continuing education courses for staff and focus on teamwork, open communication, total quality management, strategic planning, advanced nursing practice and participatory management | CULT |

(Sopow, 2020) | ability to address rapidly evolving external environmental factors | CULT |

(Sopow, 2020) | Common understanding of strategy and roadmap, Level of engagement of members and their commitment, Quality and timeliness of decisions, Execution norms that match capabilities to the environment | CULT |

(Tummers et al., 2015) | HRM practices are particularly effective for improving proactivity and vitality: high autonomy, high participation in decision making and high teamwork | CULT |

(Vaishnavi & Suresh, 2020) | customer-oriented and goal management cultures | CULT |

(Vaughn et al., 2019) | poor organisational culture (limited ownership, not collaborative, hierarchical, with disconnected leadership) | CULT |

(von Treuer et al., 2018) | capacity to change their organizational climate | CULT |

(Willis et al., 2016) | assess cultural change | CULT |

(Willis et al., 2016) | existing contextual values and belief | CULT |

(Willis et al., 2016) | promoting use of a common program language | CULT |

(Willis et al., 2016) | fostering a sense of legitimacy, cultural humility, willingness to engage and mutual respect | CULT |

(Alharbi, 2018) | resources are available | ECON |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | Organizational barriers:lack of engaged management, no culture of change, lack of financial support. Organizational promoters: organization support system change through engaged leadership; support staff by coaching, provision of information, education, multidisciplinary collaboration | ECON |

(Karalis & Barbery, 2018) | Cost was a barrier. Remuneration came in reduction of safety events and costs avoided | ECON |

(Kelly et al., 2017) | financial resources | ECON |

(Spitzer-Shohat & Chin, 2019) | sustainability of change over time | ECON |

(Vaishnavi et al., 2019) | cost effectiveness | ECON |

(Alharbi, 2018) | situational factors are aligned | EXT |

(Cane et al., 2012) | Environmental Context and Resources', 'Social Influences' | EXT |

(Han et al., 2020) | The environment dimension included external pressure, external support, network externality, installed base, and information communication | EXT |

(Holt et al., 2010a) | circumstances under which the change is occurring | EXT |

(Randall et al., 2020) | organizational context and resources | EXT |

(Sopow, 2020) | managers able to identify how internal organizational structures, systems and climates can harmonize with external climates including societal expectations, economic and technological change and public policy | EXT |

(Spitzer-Shohat & Chin, 2019) | outer and inner organizational contexts | EXT |

(Vaishnavi et al., 2019) | state of affairs, recent trends in healthcare sector | EXT |

(Vaishnavi et al., 2019) | environmental scanning, resource availability | EXT |

(Vaughn et al., 2019) | dysfunctional external relations with other hospitals, stakeholders, or governing bodies | EXT |

(Abrahamsen et al., 2017) | interprofessional collaboration model | HRM |

(Al-Hussami et al., 2018) | subjective career success | HRM |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | professional barriers: skepticism among staff, difficulty in changing behaviour, level of experience of staff, staff changes at management level | HRM |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | Organizational barriers:lack of engaged management, no culture of change, lack of financial support. Organizational promoters: organization support system change through engaged leadership; coaching, information, education, multidisciplinary collaboration | HRM |

(Bickerich & Michel, 2016) | executives with high levels of autonomy or high management support benefited from change-coaching | HRM |

(Billsten et al., 2018) | motivational readiness, institutional resources, staff attributes, and organizational climate | HRM |

(Cane et al., 2012) | 'Knowledge', 'Skills', 'Social/Professional Role and Identity', 'Beliefs about Capabilities', 'Optimism', 'Beliefs about Consequences', 'Reinforcement' | HRM |

(Feiring & Lie, 2018) | Three factors were related to capability, including (1) knowledge and acceptability of task shifting rationale; (2) dynamic role boundaries; and (3) technical skills to perform biopsies and aspirations. Five factors were related to motivation, including (4) beliefs about task shifting consequences, such as efficiency, quality and patient satisfaction; (5) beliefs about capabilities, such as technical, communicative and emotional skills; (6) job satisfaction and esteem; (7) organisational culture, such as team optimism; and (8) emotions, such as fear of informal nurse hierarchy and envy. The last two factors were related to opportunity, including (9) project planning and leadership, and voluntariness; and (10) patient preferences | HRM |

(Han et al., 2020) | The organization dimension included organizational scale, organizational culture, staff resistance to change, staff training, top management support, and organizational readiness | HRM |

(Holt et al., 2010a) | psychological factors (i.e., characteristics of those being asked to change) | HRM |

(Jackson et al., 2017) | Three related barriers included the need to address: (1) competing organizational demands, (2) differing mechanisms to integrate new interventions into existing workload, and (3) methods for referring patients to disease and self-management support programs | HRM |

(Kabukye et al., 2020) | sensitization, training, resolution of organizational conflicts | HRM |

(Kampstra et al., 2018) | improving teamwork, implementation of clinical guidelines, implementation of physician alerts and development of a decision support system | HRM |

(Karalis & Barbery, 2018) | staff education, and analysing the safety events and sharing the knowledge | HRM |

(Karalis & Barbery, 2018) | staff education, and analysing the safety events and sharing the knowledge | HRM |

(Kelly et al., 2017) | organizational functioning, better program resources and specific staff attributes, staff workloads, good organizational climate | HRM |

(Lim et al., 2019) | Motivational interviewing (MI) is internationally recognised as an effective intervention to facilitate health-related behaviour change. clinical educators could potentially play a central role as change agents within and across the complex clinical system | HRM |

(Magdzinski et al., 2018) | preparation strategies such as educational resources, managerial support and personal initiatives | HRM |

(Miake-Lye, et al., 2020) | characteristics of individuals | HRM |

(Mrayyan, 2020) | To prepare for change, nurse leaders should initiate interventions to enhance organizational readiness and facilitate the integration of change, such as continuing education courses for staff and focus on teamwork, open communication, total quality management, strategic planning, advanced nursing practice and participatory management, especially shared decision-making and policy development | HRM |

(Proctor et al., 2019) | implementation climate, participants reported the greatest increases in educational support and recognition for using EBP (evidence-based practices) | HRM |

(Randall et al., 2020) | workforce issues | HRM |

(Vaughn et al., 2019) | inadequate infrastructure (limited quality improvement, staffing, information technology or resources) | HRM |

(Han et al., 2020) | technology dimension included relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, trialability, observability, switching cost, standards uncertainty, and shared business process attributes | ICT |

(Kabukye et al., 2020) | Perceived benefits of an electronic health record (EHR) included improved quality, security and accessibility of clinical data, improved care coordination, reduction of errors, and time and cost saving, computer infrastructure, computer skills of staff | ICT |

(Kampstra et al., 2018) | high quality database | ICT |

(Pfortmiller et al., 2011) | using organizational change management techniques to facilitate adoption of a new clinical information system and discussed development of a change readiness survey tool | ICT |

Sopow, 2020 | Social technologies ensure educational, support, in- terpersonal communications and other relationships that support care teams and the work of clinical and other staff and effective relationship with patients | ICT |

Sopow, 2020 | Clinical/work technologies target the use of proper diagnosis and treatment methods technologies, appli- cation of agreed upon standards of care, engaging pa- tients in their treatment, and ensuring effective work process in support of effective care | ICT |

Sopow, 2020 | Information technologies provide information entry, organization, access, exchange, and reporting activities for effective service and organizational support | ICT |

(Vaishnavi et al., 2019) | technology advancement and interdependence among departments | ICT |

(Vaishnavi et al., 2019) | innovativeness | ICT |

(Vaughn et al., 2019) | inadequate infrastructure (limited quality improvement, staffing, information technology or resources) | ICT |

(Willis et al., 2016) | promoting use of a common program language | ICT |

(Proctor et al., 2019) | implementation leadership skills to adopt or improve the delivery of EBP (evidence-based practices) | LEAD |

(Alharbi, 2018) | organizational members' willingness to accept and implement change | LEAD |

(Al-Hussami et al., 2018) | organizational commitment, organizational support | LEAD |

(Al-Hussami et al., 2018) | leadership behavior | LEAD |

(Al-Hussami et al., 2017) | leadership guidance program that can promote nurses managers' knowledge of leadership and, at the same time, to enhance their leadership competencies and quality of work to promote their readiness for change in healthcare organizations | LEAD |

(Amarantou et al., 2018) | Resistance to change (RtC) is (indirectly) influenced by four main factors (employee-management relationship, personality traits, employee participation in the decision-making process and job security); disposition towards change (DtC), anticipated impact of change (AIC) and attitude towards change (AtC) mediate the impact of various personal and behavioral characteristics on RtC | LEAD |

(Augustsson et al., 2017) | individual- and group-level openness to organizational change are important predictors of successful outcomes | LEAD |

(Austin et al., 2020) | individual readiness factors, and by highlighting the central role of middle manager readiness for change, how frontline providers and middle managers experienced six readiness factors: discrepancy, appropriateness, valence, efficacy, fairness and trust in management | LEAD |

(Bakari et al. 2020) | important implication for leaders of organizational change in Pakistan is that they may use this construct to unearth employee level of understanding and attitude towards change initiative to envisage mechanisms to foster employee support for change | LEAD |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | professional barriers: skepticism among staff, difficulty in changing behaviour, level of experience of staff, staff changes at management level | LEAD |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | Organizational barriers: lack of engaged management, no culture of change, lack of financial support. Organizational promoters: organization support system change throgh engaged leadership; support staff by coaching, provision of information, education, multidisciplinary collaboration | LEAD |

(Bickerich & Michel, 2016) | executives with high levels of autonomy or high management support benefited from change-coaching | LEAD |

(Billsten et al., 2018) | motivational readiness, institutional resources, staff attributes, and organizational climate | LEAD |

(Cane et al., 2012) | 'Knowledge', 'Skills', 'Social/Professional Role and Identity', 'Beliefs about Capabilities', 'Optimism', 'Beliefs about Consequences', 'Reinforcement', 'Intentions', 'Goals', 'Memory, Attention and Decision Processes', 'Emotions', and 'Behavioural Regulation' | LEAD |

(Castaneda et al., 2012) | attitudes and current efforts toward prevention, commitment to change, and capacity to implement change | LEAD |

(Feiring & Lie, 2018) | Three factors were related to capability, including (1) knowledge and acceptability of task shifting rationale; (2) dynamic role boundaries; and (3) technical skills to perform biopsies and aspirations. Five factors were related to motivation, including (4) beliefs about task shifting consequences, such as efficiency, quality and patient satisfaction; (5) beliefs about capabilities, such as technical, communicative and emotional skills; (6) job satisfaction and esteem; (7) organisational culture, such as team optimism; and (8) emotions, such as fear of informal nurse hierarchy and envy. The last two factors were related to opportunity, including (9) project planning and leadership, and voluntariness; and (10) patient preferences | LEAD |

(Han et al., 2020) | The organization dimension included organizational scale, organizational culture, staff resistance to change, staff training, top management support, and organizational readiness | LEAD |

(Hauck et al., 2013) | Leadership facilitated infrastructure development in three major areas: incorporating evidence-based practice outcomes in the strategic plan; supporting mentors; and advocating for resources for education and outcome dissemination. Transformational nursing leadership drives organizational change and provides vision, human and financial resources and time that empowers nurses to include evidence in practice | LEAD |

(Jackson et al., 2017) | Facilitators: significant commitment from the core implementation team and a desire to improve patient outcomes | LEAD |

(Jakobsen et al., 2016) | Participatory organizational interventions may improve social capital within teams and between teams and distant leaders and organizational readiness for change | LEAD |

(Kabukye et al., 2020) | strategic implementation | LEAD |

(Kabukye et al., 2020) | vision clarity, change appropriateness, change efficacy, presence of an effective champion | LEAD |

(Kampstra et al., 2018) | engagement and leadership | LEAD |

(Karalis & Barbery, 2018) | supportive leadership | LEAD |

(Kelly et al., 2017) | Motivation for change | LEAD |

(Lim et al., 2019) | Motivational interviewing (MI) is internationally recognised as an effective intervention to facilitate health-related behaviour change. clinical educators could potentially play a central role as change agents within and across the complex clinical system | LEAD |

(Lundmark et al., 2020) | line managers' leadership during an organizational intervention. Employee readiness for change was positively related to constructive leadership, and negatively related to both passive and active destructive leadership | LEAD |

(Masood & Afsar, 2017) | transformational leadership through psychological empowerment, knowledge sharing, and intrinsic motivation fosters nurse's innovative work behavior | LEAD |

(Mazur et al., 2019) | willingness of executive employees to actively support and participate in the change management process | LEAD |

(Morin et al., 2016) | relations among latent constructs reflecting change-related beliefs (necessity, legitimacy, support) and psychological reactions (psychological empowerment, affective commitment to change). Our findings suggest that psychological empowerment and affective commitment to change represent largely orthogonal reactions, that psychological empowerment is influenced more by beliefs regarding support, whereas affective commitment to change is shaped more by beliefs concerning necessity and legitimacy | LEAD |

(Mrayyan, 2020) | Successful leaders support employees' creative ideas, focus on the timing of the change, and provide training on change management | LEAD |

(Nelson-Brantley & Ford, 2017) | attributes of leading change were identified: (a) individual and collective leadership; (b) operational support; (c) fostering relationships; (d) organizational learning; and (e) balance | LEAD |

(Nuno-Solinis, 2018) | staff motivation | LEAD |

(Nuno-Solinis, 2018) | higher organizational effort | LEAD |

(Oygarden & Mikkelsen, 2020) | strategic translations may foster readiness for change | LEAD |

(Proctor et al., 2019) | implementation climate, participants reported the greatest increases in educational support and recognition for using EBP (evidence-based practices) | LEAD |

(Puchalski Ritchie & Straus, 2019) | higher organizational effort and staff motivation for overcoming barriers and setbacks | LEAD |

(Randall et al., 2020) | perceive management to be high quality, they are more supportive of organizational changes that promote evidence-based practice | LEAD |

(Schultz et al., 2019) | the failure to manage the people' element and engage employees hampers the success of that change | LEAD |

(Sicakyuz & Yuregit, 2020) | staff commitment by including them in decision-making and process changing | LEAD |

(Sola et al., 2016) | extra-effort, efficiency and satisfaction | LEAD |

(Sola et al., 2016) | questionnaire measures leadership styles, attitudes and behaviour of managers (transformational, transactional and laissez-faire) | LEAD |

Sopow 2020 | LEADERSHIP: Convergent, generative, unifying | LEAD |

Sopow 2020 | Common understanding of strategy and roadmap, Level of engagement of members and their commitment to participate, Quality and timeliness of decisions, Execution norms that match capabilities to the environment | LEAD |

(Vaishnavi et al., 2019) | organizational leadership | LEAD |

(von Treuer et al., 2018) | capacity to change leadership practices | LEAD |

(Willis et al., 2016) | foster distributed leadership (informal leaders, including "opinion leaders") | LEAD |

(Willis et al., 2016) | align vision and action | LEAD |

(Willis et al., 2016) | make incremental changes within a comprehensive transformation strategy | LEAD |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | Organizational barriers: lack of engaged management, no culture of change, lack of financial support. Organizational promoters: organization support system change throgh engaged leadership; support staff by coaching, provision of information, education, multidisciplinary collaboration | MA |

(Kampstra et al., 2018) | improving teamwork, implementation of clinical guidelines, implementation of physician alerts and development of a decision support system, audits, frequent reporting and feedback, patient involvement, communication, standardization | MA |

(Kampstra et al., 2018) | high quality databas | MA |

(Pfortmiller et al., 2011) | using organizational change management techniques to facilitate adoption of a new clinical information system and discussed development of a change readiness survey tool | MA |

(Sopow 2020) | Administrative technologies address the proper administrative auspices, structures and processes for innovations including design, staffing, training, financial support and evaluation, and coordination with other units-build versus buy, costing, contracting, cost allocation, return on investment are illustrative issue | MA |

(Al-Hussami et al., 2018) | organizational commitment, organizational support | ORG |

(Bastemeijer et al., 2019) | Organizational barriers:lack of engaged management, no culture of change, lack of financial support. Organizational promoters: organization support system change throgh engaged leadership; support staff by coaching, provision of information, education, multidisciplinary collaboration | ORG |

(Benzer et al., 2017) | organization structure dimensions of differentiation and integration impact readiness for change at the individual level of analysis by influencing four key concepts of relevance, legitimacy, perceived need for change, and resource allocation | ORG |

(Billsten et al., 2018) | motivational readiness, institutional resources, staff attributes, and organizational climate | ORG |

(Han et al., 2020) | The organization dimension included organizational scale, organizational culture, staff resistance to change, staff training, top management support, and organizational readiness | ORG |

(Holt et al., 2010b) | level of analysis (i.e., individual and organizational levels) | ORG |

(Jackson et al., 2017) | Three related barriers included the need to address: (1) competing organizational demands, (2) differing mechanisms to integrate new interventions into existing workload, and (3) methods for referring patients to disease and self-management support programs | ORG |

(Jakobsen et al., 2020) | Participatory organizational interventions may improve social capital within teams and between teams and distant leaders and organizational readiness for change | ORG |

(Kabukye et al., 2020) | organizational flexibility and collective self-efficacy | ORG |

(Kelly et al., 2017) | organizational functioning, better program resources and specific staff attributes, staff workloads, good organizational climate | ORG |

(Minyard et al., 2018) | contextual factors within the organization | ORG |

(Mrayyan, 2020) | having developed plans for expanding ambulatory care or enhancing continuity of care, including nurses on all committees, and involving them in policy development and strategic planning efforts | ORG |

(Oygarden & Mikkelsen, 2020) | how the use of editing rules in a strategic translation process impacts readiness for chang | ORG |

(Randall et al., 2020) | organizational functioning | ORG |

(Spitzer-Shohat & Chin, 2019) | outer and inner organizational contexts | ORG |

(Tummers et al., 2015) | HRM practices are particularly effective for improving proactivity and vitality: high autonomy, high participation in decision making and high quality teamwork | ORG |

(Spitzer-Shohat & Chin, 2019) | process of translating and implementing equity interventions throughout organizations; organizational and patient outcomes | OTHER |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gabutti, I., Colizzi, C. & Sanna, T. Assessing Organizational Readiness to Change through a Framework Applied to Hospitals. Public Organiz Rev 23, 1–22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00628-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00628-7