Abstract

The author investigated the relationship between gender diversity and organizational inclusion and moved forward to examine whether gender diversity, diversity management and organizational inclusion predict workplace happiness by collecting 320 questionnaires from academics in three public universities in Egypt. A t-test was used to identify how gender may affect perceptions of diversity management and organizational inclusion. Hierarchical regressions were applied to test whether gender diversity, diversity management, and organizational inclusion can predict workplace happiness. The findings showed no relationship between gender diversity and organizational inclusion, and the authors confirmed that gender diversity, diversity management, and organizational inclusion can effectively predict workplace happiness. Theoretical and empirical implications are discussed at the end of the paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the concept of diversity has gained currency in management literature (Wikina 2011). Different employers have considered it a driver for their continuity and a tool for accessing new markets (Ozgener 2008; Madera et al. 2013). According to Kundu and Mor (2017), there is a growing trend from employees nowadays to join institutions that value diversity and respect differences. Therefore, organizations have started to regularly review and update their diversity-related policies and/or activities in order to realize an inclusive work context which ensures justice, engagement, tolerance and equal opportunities for staff regardless of their differences (Healy et al., 2010). This is in line with what has been mentioned by Roosevelt Thomas (1990), who points out that the main mission of any diversity management protocol should be to develop an organizational climate that appreciates differences and respects an individual’s uniqueness. Consequently, the implementation of effective diversity management procedures may entail a dramatic change in an organization’s culture, values and traits (Celik et al., 2011; Shore et al., 2011; Mousa 2018a; Mousa, 2018b; Mousa et al. 2019a). The same has been affirmed by a research study (2019), who highlighted that treating all employees as insiders may regularly require tailoring activities/procedures through which employees can feel involved, supported, engaged and that they belong.

Like other aspects and phenomena in human resources management, diversity management is based on social exchange theory, which says that investments in the staff of an organization (pay, promotion, development opportunities, information, status, love etc.) are constantly met by positive employee returns (performance, commitment, citizenship behaviour) towards the organization they work in (Blau, 1964; Van de Voorde et al., 2012 and Paauwe et al., 2013). Furthermore, and according to Simons (2002) and Jonsen et al. (2011), the roots of diversity management discourse can be traced back to equal employment initiatives and affirmative action protocols in the US in the 1960s, and since then this concept has attracted attention from researchers in disciplines such as public policy, public administration, sociology, humanities, marketing and public relations. However, HRM scholars have only touched upon this vast research field over the past two decades and since perceiving the demographic changes in the labour market, growing interest in business ethics, corporate orientation to go global and government policies in Europe to include foreigners and immigrants in their labour markets (Ravazzani, 2016).

Studies by Selden and Selden (2001) and Ashikali and Groenveld (2015) have shown that organizations in western countries have a long history in implementing affirmative action, equal employment opportunities and other diversity-related mechanisms that ensure the fair representation of minority groups at different organizational levels. This may come as a result to attempts by these organizations to build diversity, which often entails attracting, hiring, developing and retaining a diverse range of elite personnel regardless of their differences in order to boost the organization’s performance (Ely and Thomas, 2001; Nishii, 2013;). However, Kirton and Greene (2010) indicate that the main shortcoming of diversity management is its complete focus on representing, developing and retaining minorities. This sometimes fuels negative feelings and behaviours in members of majority groups towards their workplace. Consequently, Guillaume et al. (2014) affirm that diversity management may be seen as a threat to the dominant culture in organizations if it is not properly designed and adopted.

Kundu and Mor (2017) highlight that any sound management of diversity should start by assessing employee perceptions of how their organization deal with dissimilarities and what actions are taken to promote workplace inclusion. Needless to say that such perceptions of diversity differ from one individual to the next because of differences in age, gender, education, religion and work experience. A research study done by Mousa (2017) explored how nurses perceive cultural diversity in public hospitals in Egypt and one of the main findings was that the nurses receive lower assessment rates and feel discriminated only when their managers are men.

Numerous authors (e.g. Cox, 1991; Thomas, 1991; Richard and Johnson, 2001; Oslen and Martins, 2012 and Ravazzani, 2016) differentiate between the following three stages or dynamics of managing diversity in different work settings. First, assimilating minorities, which focuses on the fair representation of different groups through adopting quota systems. Second, integrating diversity, which entails voluntary actions by organizations to form a pool of employees who are different in religion, race, nationality, age, language and so on, which is often seen as an attempt to secure legitimacy through meeting local socio-cultural expectations. Third, leveraging variety, which entails the organization planning sets of activities to include diverse staff that the organization considers a main driver of competitive advantage. This occurs through employing heterogeneous teams and securing team development, training and learning opportunities (Janssens and Zanoni, 2014).

According to Vuuren et al. (2012, p. 156), cultural diversity means “differences in ethnic background, historical origins, religion, socio-economic status, personality, disposition, nature and more”. Heuberger, Gerber and Anderson (2010, p. 107) define it as “many types of differences such as racial, ethnic, religious, gender, sexual orientation and physical ability, among others”. Kundu (2001); Mousa et al. (2020a, b), Avery et al. (2008), Jain (1998), King et al. (2011), Windscheid et al. (2018), Humphrey et al. (2006) and Heuberger et al. (2010) highlight that cultural diversity refers to the co-existence of people who are affiliated with different social classes at different organizational levels. Consequently, the management of cultural diversity entails realizing individual career aspirations without being hurdled because of religion, gender, family status, race or related factors (Nishii, 2013). This is what has been highlighted and announced by the anti-discrimination policies that US organizations have adopted since 1960 (Tereza and Fleury, 1999). Dogra (2001) highlights the fact that early studies on cultural diversity have focused on racial discrimination. Since 1990, the scope of research on cultural diversity has expanded to include the assessment of coherence and/or integration in different societal and work contexts.

Egypt, which is considered one of the oldest and richest civilizations and often perceived as one of the leading countries in the Middle-East in terms of history and culture, and population size, witnesses remarkable inequalities in terms of gender, age, religion and political affiliation (a research study, 2018b). In the Egyptian context, cultural diversity and its management have not been perceived as being of research interest by practitioners or academics. A research study done by Alas and Mousa (2016) and another by Mousa and Alas (2016) assert that Egyptians and the current Egyptian political regime tend to introduce their country as a model of tolerance and humanity that other countries should address and follow despite the lasting state of division in terms of religion, gender, political ideology and even linguistic dialect this country suffers from. Moreover, Egyptians affirm from time to time that discrimination has no value in their behavioural dictionary. This may justify the scarcity of research on cultural diversity and its management in Egyptian societal and organizational settings.

Alas and Mousa research study (2016) conducted a number of semi-structured interviews with MBA students in a private business school in Egypt and assert the need to consider diversity management as part of the current MBA courses or to tailor specific courses and training sessions on cultural diversity in order to deal with the state of division in Egyptian society since the January 2011 revolution and the growing conflict between Egyptians who classify themselves based on religion, gender and political ideology. Hofstede and Hofstede (2005) discuss the following four dimensions of shaping culture: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism and masculinity. According to Mousa (2017), masculinity, which is the basis of the superiority men have within Egyptian society, and individualism, which reflects how the family influences individual behaviour, are the two dominant dimensions in Egyptian culture. Moreover, the same study elaborates that the man is the breadwinner and dominant voice in the Egyptian family, while the woman is mainly responsible for raising children. The author of the same study conducted a number of interviews with nurses in a public hospital in Egypt and concluded that nurses often receive low assessments if their managers are men. Moreover, there is a kind of exclusion and/or marginalization of Christian nurses because of their religion. Moreover, a study by Mousa (2018a) focused on physicians in Egyptian public hospitals to address the effect of cultural diversity challenges on organizational cynicism among those physicians, has indicated a positive correlation between discrimination as one of the main cultural diversity challenges and the negative attitudes physicians have against their colleagues and their workplace (labelled as organizational cynicism).

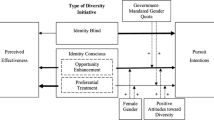

Given the fact that diversity management is new to Egyptian organizational settings and that studies of diversity are still at an embryonic stage in Egyptian academia, the author of this paper addresses academics in three three public universities in an attempt to, first, explore how gender diversity may affect perceptions of diversity management policies and the sense of organizational inclusion. Second, to examine the association between diversity management and organizational inclusion, and lastly, to identify the relationship between gender diversity, diversity management, organizational inclusion and workplace happiness in the selected context. The impetus for the study lies in addressing diversity management and organizational inclusion in an organizational setting that suffers from clear cases of division and conflict as is common in other socio-cultural and political settings in Egypt today. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: first the author will present the theoretical background and hypotheses, followed by the study design, then the results, and lastly the discussion, implications, conclusion, limitations and future research.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Gender Diversity and Diversity Management

Gender diversity has become a major challenge for organizations. Politically, Gatrell and Swan (2008) indicate that the unfair representation of women in the labour market is unacceptable. Moreover, Joshi et al. (2015) highlight that gender diversity stimulates more economic returns through fuelling productivity. Solakoglu and Demir (2016) point out that the effective management of gender diversity entails positive organizational outcomes such as accessing new markets, building a good corporate image and enhancing employee commitment. This comes in agreement with Farrell and Hersch (2005) and Smith et al. (2005), who have indicated a positive association between gender diversity and firm performance. From their side, Vanderbroeck and Wasserfallen (2017) affirm that selecting the right person for the right job is a dilemma in business life today. Therefore, they affirm the need for a regular competency framework assessment for measuring daily employee performance regardless of gender in order to maintain more equitable career paths.

Larkin et al. (2012) and Perrault (2015) demonstrate that gender-balanced staffing has become high on the socio-political and economic agendas undertaken by many western governments. In 2016, the German government, for example, decreed a law forcing public-owned organizations to follow a specific quota for hiring women (Windscheid 2018). Moreover, organizations – whether public or private – have to regularly and publicly report their gender diversity policies and/or actions (Ali et al., 2014).

In academia, Su et al. (2015) confirm that women faculty face many career disadvantages such as under representation as a result of extensive family responsibilities. The same has been confirmed by Dominici et al. (2009), who note the under representation of women in academic administrative positions such as rectors, deans and chairs of academic departments. According to Su et al. (2015), the chairs of academic departments play a major role in shaping the gender diversity scene and they can effectively implement a sound gender diversity system if they have proper levels of authority, information, financial resources and support. Accordingly, the author proposes the first hypothesis as follows:

-

H1: Female academics well-perceive diversity management practices more than their male colleagues.

Gender Diversity, Diversity Management and Organizational Inclusion

The concept of inclusion appeared in 1980 and was introduced by researchers in the field of education (Gilhool, 1989). Later, sociology researchers used the concept to describe the effective fair interpersonal relationships between individuals in the same society (Babacan, 2005). Since 1990, management scholars have started to focus on inclusion and could be classified into two schools of thought. Scholars of the first school pay attention to the individual’s perceptions of the degree of involvement, integration and equality experienced in his workplace (Lirio et al., 2008; Shore et al., 2011, Mousa & Ayoubi, 2019a, b, Mousa et al. 2020a, b). Consequently, the employee’s sense of belonging, involvement and justice is constantly addressed by researchers in this school. In the second school, scholars target the procedures and actions undertaken by different organizations to ensure engagement and workplace harmony (Mor Barak, 2000; Roberson, 2006). According to Tang et al. (2017), organizational inclusion has been taken seriously, drawing on the recommendation of the “workforce 2000” project initiated by both the US Department of Labor and the Hudson Institute in 1987. The results of the project highlight the need to shift from diversity management to organizational inclusion as a result of the growing number of diverse individuals who access the labour market in the USA and other western countries. Romer (1990), Jansen et al. (2014) and Tang et al. (2015) confirm that inclusion is the mechanism organizations can employ to constitute an organizational identity and subsequently eliminate workplace conflicts between diverse employees.

For Davidson and Ferdman (2002) and Pless and Maak (2004), organizational inclusion refers to the effective participation and/ or engagement of individuals in realizing their goals and those of their organization while feeling respected and appreciated. Davidson (2011) and Humberd et al. (2015) highlight that developing an inclusive culture and fostering open communication are essential to maintaining organizational inclusion. Many authors (e.g. Cox, 1994; Ainscow and Sandill, 2010; Nishii and Mayer, 2009; Ainscow and Sandill, 2010) elaborate that HR systems, leadership style and internal values strongly affect the level of organizational inclusion.

According to Booysen (2007), the concept of diversity management differs from the concept of organizational inclusion, and they both vary across organizations and researchers. Wah (1999), Guillory and Guillory (2004), April et al. (2009) and Van Dijk et al. (2012) define diversity as the tangible and intangible differences among individuals, while organizational inclusion entails understanding and utilizing these individual differences for the betterment of individuals and their organizations. Daya (2014) elaborates that diversity management involves a kind of fair representation for different societal demographic populations at different organizational levels. Accordingly, diversity management starts and ends as a set of managerial actions while organizational inclusion starts as a managerial action but ends as an individual feeling (Harrison and Klein, 2007). Human (2005) and Daya (2014) point out that implementing organizational inclusion may involve a change in an organization’s vision, strategy, culture, communication policies, HR systems, leadership style and moral values. Accordingly, the author proposes the following two hypotheses:

-

H2: There is an insignificant statistical relationship between gender diversity and organizational inclusion.

-

H3: Diversity management is positively associated with organizational inclusion.

Gender Diversity, Diversity Management, Organizational Inclusion and Workplace Happiness

Due to the growing academic focus on positive psychology over the past decade, workplace happiness has increasingly become a topic of interest (Guest, 2017). Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2014) consider workplace happiness as a river for many positive work attitudes such as fewer turnover intentions and absenteeism levels. Fisher (2010) highlights that the feeling of happiness at work entails an implicit assessment of one’s job including its duties, future and responsibilities. This may justify why the same author affirms its importance in shaping both the organization’s continuity and the employee’s future organizational behaviour.

Generally, the concept of happiness has received considerable attention from psychology and philosophy researchers who confirm that individuals feel happy if they exhibit higher emotional intelligence (Carmelie et al., 2009) and stable personal life (marriage, owning house, etc.) (Weimann et al., 2015). Erdogan et al. (2012) indicate that public health and public policy researchers have also paid attention to the determinants of individual happiness. Xanthopoulou et al. (2012) confirm that the concept of workplace happiness is still underdeveloped. The same has been confirmed by Kristensen and Johansson (2008), who indicate that management scholars have only tended to show interest in workplace happiness over the past decade in an attempt to stop or at least eliminate negative emotions and cynicism from stiff competition, heavy work-loads and unfair treatment in different work settings. Moreover, Erdogan et al. (2012) highlight the need for more empirical research on happiness at work.

According to Fisher (2010), workplace happiness reflects an attitudinal construct comprised of three dimensions: engagement, job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. Moreover, happiness at work is often derived from personal experiences the employee has had, witnessed or even heard about. Zelenski et al. (2008) and Erdogan et al. (2012) consider that workplace happiness is largely based on leadership style, workplace justice, communication policies, organizational culture and more. It is no surprise therefore that Weimann et al. (2015) state that workplace happiness is not fixed but may change as a response to changes in work conditions (development opportunities, financial remuneration, promotion, assessment, etc.). Accordingly, Fisher (2010) perceives workplace happiness as healthy positive feelings an employee maintains towards the job itself (work atmosphere, feeling at work, job title), job characteristics (pay, development opportunities and assessment) and the organization as a whole. Accordingly, the author proposes the following hypothesis:

-

H4: Gender diversity, diversity management and organizational inclusion can statistically predict workplace happiness.

Methodology

Sample

The conceptual framework of the present quantitative study was drawn from previous literature on diversity management, organizational inclusion and workplace happiness. To the best of the author’s knowledge, the relationship between gender diversity, diversity management perception, organizational inclusion and workplace happiness has not been addressed before, particularly within the context of universities.

The study was conducted on academics in three public universities located in Egypt. The main reason for choosing these universities was one author’s relationship with a number of academics who work there in addition to the approval of those universities to collaborate with the author of the present paper. The first is a university with 360 academics, the second has 260, and the third 340 academics. Accordingly, the total sample size (study community) the authors of the present paper could address is 960 academics. All the academics invited to participate are Egyptian, and many of them completed their education (MA and/or PhD) in Western countries.

The author targeted all academics in the chosen universities and decided to employ a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. He distributed 960 questionnaire forms and successfully collected 320 completed questionnaires. Before distributing the questionnaire, the author decided to rely on purposive sampling in which a questionnaire was handed to every academic in the chosen universities. The choice of purposive sampling ensures that every academic is contacted and represented in the collected sample, and this reduces the possibility of a bias.

Measures

Concerning the measures, the author of this paper found that only two variables – diversity management and organizational inclusion – have previously been researched. Accordingly, the author had to develop a model for workplace happiness, for which there is no commonly accepted model. The following describes the measures used in the questionnaires.

For diversity management, the author used six items of workplace diversity management developed by Mor Barak et al. (1998) after updating them to fit the Egyptian organizational academic setting. The following is an example of the items included in Mor Barak’s 1998 model: Our university makes promotion and tenure decisions fairly and regardless of employee differences.

For organizational inclusion, the author used the organizational inclusion model (6 items) developed by Mousa and Puhakka (2019) without changing any of them as they were originally designed and tested in an Egyptian organizational context. The following are examples of the items included in A research study by Mousa and Puhakka’s 2019 model of organizational inclusion: My workplace respects the uniqueness of academics, I did not feel any discrimination while working in my current workplace and My workplace treats all academics as insiders.

For workplace happiness, the author, based on their items on the study by Fisher (2010), who elaborates that workplace happiness is a construct of three dimensions: engagement, job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. Proposes the following six items to test workplace happiness:

-

1)

I have positive emotions towards my university and accordingly I continue my organizational membership.

-

2)

I am satisfied with my job’s duties, responsibilities and description.

-

3)

I am satisfied with my current salary, development opportunities and career aspirations.

-

4)

I feel passionate to engage, integrate and effectively participate with my colleagues in performing our job responsibilities.

-

5)

I feel pride in being affiliated with my current university and work with my current colleagues.

-

6)

I feel a sense of involvement, equality, security, safety and harmony in my current workplace.

Results

The following presents the reliability analysis for diversity management, organizational inclusion workplace happiness and gender using Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha is used to assess the internal consistency of each of the variables used in the study. As depicted in Table 1, there is a significant correlation among the four variables (ranging from 0.152 to 0.362). Table 1 shows the reliability analysis for the four variables using Cronbach’s alpha.

For H1 and H2, the author used a t-test to identify how gender may affect perceptions of diversity management and organizational inclusion. As shown in Table 2, the results show a relationship between gender diversity and perceptions of diversity management (t = −320, P < 0.05). For female academics, the mean is 3.88, while the standard deviation is 0.80; meanwhile, the mean for male academics is 3.20 and the standard deviation 0.68. The results indicate that female academics perceive, appreciate and respect diversity policies at their universities better than their male colleagues. Therefore, H1 is supported. Table 2 also shows that there are no considerable difference in the perception of male and female academics regarding their perceived level of organizational inclusion. As shown below in Table 2, M = 3.50 while SD = 0.68 for female academics, and M = 3.48 and SD = 0.67 for their male colleagues. Accordingly, H2 is also supported.

For H3, the author used a chi-square test to explore the association between diversity management and organizational inclusion. All expected cell frequencies were greater than five.

The table reflects a statistically significant association between diversity management and organizational inclusion; χ2(1) = 74.439, p = .000. φ = 0.624, p = .000 reflects a strong association between the two variables Tables 3 and 4.

For H4, which addressed the relationship between gender and workplace happiness via the mediation of diversity management and organizational inclusion, a three-step hierarchical regression analysis was used after securing the availability of the conditions needed to adopt this type of regression (Miles and Shevlin, 2001). The author verified that there were no signs of multicollinearity in any of the three regression variables. All tolerance values are greater than 0.20 and the VIF are less than four. When adopting the first step of the hierarchical regression, gender was not found to be a significant predictor of workplace happiness (t = 1.511, P = 0.08) and accounted for 1.9% of the variance. In the second step, diversity management was added and found to be a significant predictor of workplace happiness (t = 5.622, P < 0.01) R2 increased to 0.129 and ∆R2 = 0.110. The second model added an 11% increase to the variance. In the third step, organizational inclusion was also added (t = 4.981, P < 0.01) and R2 increased to 0.249 and ∆R2 = 0.120. Therefore, the second model added a 12% increase to the variance. To summarize, gender alone was not found to be a significant predictor of workplace happiness while diversity management and organizational inclusion were positively related to workplace happiness. Therefore, H4 was supported.

Discussion

The results showed that female academics show a more favourable perception of diversity management policies than their male colleagues. This is logical result and comes in line with Kirton and Greene (2010), who indicate that diversity management prioritizes the fair representation of women, minorities and the disabled. Therefore, members of such groups develop and maintain positive feelings towards any diversity-related policy and/or procedure. Kundu and Mor (2017) and Mousa (2018) elaborate that diversity perception differs from one individual to another based on gender, religion, race etc. However, building a business based on diversity, which entails hiring and retaining personnel regardless of their cultural differences, was constantly met by positive perceptions particularly from minority and lower-class affiliated individuals (female academics in this case). This indicates why female academics perceive diversity management policies and/or businesses based on diversity initiated by their universities more clearly than their male colleagues. What may contribute to this result is the fact that women faculty face many career disadvantages and under representation, particularly in leading academic positions, such as rectors, deans and heads of academic departments as elaborated by Su et al. (2015). Consequently, any organized and/or planned effort to correct their current situation and create more opportunities and/or representation for them should be perceived and highly respected.

The fact that there is no relationship between gender diversity and organizational inclusion as proved by the results, as was expected by the author. According to April et al. (2009), Van Dijk et al. (2012) and A research study by Mousa and Puhakka (2019), organizational inclusion entails securing equal opportunity for every organizational member to effectively participate, integrate and engage without paying attention to individual differences in gender, ethnicity, sexual preference and so on. This means that implementing a sound organizational inclusion policy ensures that all cultural differences (gender in this case) are ignored and only offers assistance to individuals in attaining both individual and organizational goals, while feeling involved, appreciated and respected. This explains the insignificant relationship between gender diversity and organizational inclusion.

Diversity management was reported to be positively associated with organizational inclusion. For Booysen (2007) diversity management differs from organizational inclusion. The same has been highlighted by Daya (2014), who indicates that diversity management involves fair representation for individuals who affiliated with different societal demographics at different levels of the organization, whereas organizational inclusion reflects utilizing the differences among staff for the betterment of every staff member as well as their organization. This means that organizational inclusion can be seen as a positive outcome of a diversity management policy or, as described by Human (2005) and Harrison and Klein (2007), organizational inclusion is the bright side of diversity management. Accordingly, the positive association between diversity management and organizational inclusion is also considered a logical result and fits previous studies. Furthermore, the result obtained regarding H3 is in line with Oslen and Martins (2012) and Ravazzani (2016), who indicate that organizations (universities in this case) often start by using affirmative actions and quota systems when managing diversity, then they constitute a pool of different personnel to meet socio-cultural expectations, and finally, they leverage variety through implementing a planned inclusive atmosphere through which diverse employees feel like insiders. This affirms the positive association between diversity management and organizational inclusion.

Lastly, the results showed that gender diversity, diversity management and organizational inclusion are predictors of workplace happiness. Fisher (2010) considers workplace happiness as an attitudinal construct that involves three dimensions: engagement, job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. Moreover, Zelenski et al. (2008), Fisher (2010), Mousa et al. (2020a), Mousa et al. (2020b) and Erdogan et al. (2012) highlight that workplace happiness comes as an outcome of workplace justice, an open communication policy, inclusive work culture and others. This explains to a large extent how both diversity management, which is concerned with workplace justice, and organizational inclusion, which promotes openness, integration and respect, are perceived as determinants or may even be drivers of workplace happiness.

Implications

As seen in the results of this study, diversity management and organizational inclusion play a significant role in shaping and maintaining workplace happiness. Accordingly, the author proposes that the administration of the universities involved in the study establish units for managing diversity and inclusion. Such units should collaborate with HR personnel when recruiting academics to ensure a merit-based approach. This approach views academics/employees based on their educational credentials regardless of their cultural differences such as gender, religion, political ideology and so on. The administration of the universities in this study should also employ competency-based assessment when evaluating the performance/productivity of academics. This competency-based assessment evaluates academics in terms of research production, teaching skills, and practical contributions regardless of their cultural differences (gender in this case). Lastly, and to promote engagement and/or integration, an open communication policy should be enhanced across different academic levels. This would encourage academics to discuss and express their fears, hopes, worries and suggestions with the heads of their departments and rectors of their schools. This would not only boost productivity but also fuel the academic’s sense of involvement and insider-ness. Consequently, workplace happiness will be enhanced. Lastly and given what has been highlighted by Morphet (2008), employees who serve in the public sector are similar to those working in the private one in facing work challenges of anxiety, stress, and burnout. Morphet (2008) highlights that new governance structure, funding possibilities, and mechanisms of service delivery that the public sector emphasize have reframed public servants’ job responsibilities, duties, and tasks. This may justify why concepts such as work/life balance and workplace happiness have started to find a space on the work practices done by public administration personnel (Mousa, 2018; Mousa et al., 2019b). Accordingly, the author of this paper recommends that the administration of public universities also to pay more attention to the level of happiness their academics experience. This can be tested regularly by addressing those academics’ affective commitment and job satisfaction from time to time.

Conclusion, Limitations and Future Research

This study focused on academics in three public universities operating in Egypt to explore the relationship between gender diversity and diversity management perceptions, gender diversity and organizational inclusion, and diversity management and organizational inclusion and finally whether gender diversity, diversity management and organizational inclusion predict workplace happiness or not. Based on the three different statistical tests used by the author to analyse the completed questionnaire forms, the author found that female academics maintain more favourable feelings/perceptions towards diversity management than their male colleagues. Moreover, there is no relationship between gender diversity and organizational inclusion, whereas a significant positive association between diversity management and organizational inclusion has been discovered. Finally, the author confirmed that gender diversity, diversity management and organizational inclusion can effectively predict workplace happiness.

Limitations

The author only addressed academics in public universities in Egypt without paying attention to private ones there. This limits the author’s ability to generalize the results. The second limitation is the common statistical shortcoming of collecting data from the same respondents, which sometimes leads to a statistical inflation of the results produced.

Future Research

The author suggests other HR researchers test the same hypotheses in private universities, which represent a completely different organizational context as explained earlier. Furthermore, the author suggests HR researchers test the same hypotheses in non-academic organizational settings such as hospitals, schools, ministries, state-owned organizations and also small and medium sized enterprises. The author finds it reasonable to suggest that HR researchers collaborate with public policy, sociology and humanities-affiliated academics/researchers to produce more trans-disciplinary or multi-disciplinary research on the same topic. This may yield more in-depth knowledge about the topic and the four main variables, namely: gender diversity, diversity management, organizational inclusion and workplace happiness.

References

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(4), 401–416.

Alas, R., & Mousa, M. (2016). Cultural diversity and business schools’ curricula: A case from Egypt. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 14(2), 130–137.

Ali, M., Ng, Y. L., & Kulik, C. T. (2014). Board age and gender diversity: A test of competing linear and curvilinear predictions. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(3), 497–512.

April, K., Katoma, V., & Peters, K. (2009). Critical effort and leadership in specialised virtual networks. Annual Review of High Performance Coaching & Consulting, 1(1), 187–215.

Ashikali, T., & Groeneveld, S. (2015). Diversity management for all? An empirical analysis of diversity management outcomes across groups. Personnel Review, 44(5), 757–780.

Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., & Wilson, D. C. (2008). What are the odds? How demographic similarity affects the prevalence of perceived employment discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 235–249.

Babacan, H. (2005). “Challenges of inclusion: Cultural diversity, citizenship and engagement”, in proceedings of international conference on engaging communities. QLD: Brisbane.

Blau, P. (1964). Power and exchange in social life. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Booysen, L. (2007). Managing cultural diversity: A south African perspective. In K. April & M. Shockley (Eds.), Diversity in Africa: The coming of age of a continent (pp. 51–92). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Carmeli, A., Yitzhak-Halevy, M., & Weisberg, J. (2009). The relationship between emotional intelligence and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24, 66–78.

Celik, S., Ashikali, T., & Groeneveld, S. (2011). De invloed van diversiteitsmanagement op de binding van werknemers in de publieke sector. De rol van transformationeel leiderschap. (The binding effect of diversity management on employees in the Dutch public sector. The role of transformational leadership). Tijdschrift voor HRM, 14(4), 32–53.

Cox, T. (1994). A Comment on the Language of Diversity. Organization, 1(1), 51–58.

Cox, T. H. (1991). The multicultural organization. Academy of Management Executive, 5(2), 34–47.

Davidson, M., & Ferdman, B. (2002). Inclusion: what can I and my organization do about it? The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist, 39(4), 80–85

Davidson, M. (2011). The end of diversity as we know it: why diversity efforts fail and how leveraging difference can succeed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Daya, P. (2014). Diversity and inclusion in an emerging market context, equality diversity and inclusion. An International Journal, 33(3), 293–308.

Dogra, N. (2001). The development and evaluation of a programme to teach cultural diversity to medical undergraduate students. Medical Education, 35(3), 232–241.

Dominici, F., Fried, L. P., & Zeger, S. L. (2009). So few women leaders. Academe, 95(4), 25–27.

Ely, R. J., & Thomas, D. A. (2001). Cultural diversity at work: the effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(2), 229–273.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., & Mansfield, L. R. (2012). Whistle while you work a review of the life satisfaction literature. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1038–1083.

Farrell, K. A., & Hersch, P. L. (2005). Additions to corporate boards: the effect of gender. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11(1), 85–106.

Fisher, C. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 384–412.

Gatrell, C., & Swann, E. (2008). Gender and diversity in management: a concise introduction. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Gilhool, T. K. (1989). The right to an active education: from brown to PL 94-142 and beyond. In D. K. Lipsky & A. Gartner (Eds.), Beyond separate education: quality education for all (pp. 243–253). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company.

Guest, D. E. (2017). Human resource management and employee well-being: towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 22–38.

Guillaume, Y. R., Dawson, J. F., Priola, V., Sacramento, C. A., Woods, S. A., Higson, H. E., Budwar, P. S., & West, M. A. (2014). Managing diversity in organizations: an integrative model and agenda for future research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(5), 783–802.

Guillory, W., & Guillory, D. (2004). The roadmap to diversity, inclusion, and high performance. Healthcare Executive, 19(4), 24.

Harrison, D. A., & Klein, K. J. (2007). What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1199–1228.

Healy, G., Kirton, G., & Noon, M. (2010). Equality. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke: Inequalities and Diversity.

Heuberger, B., Gerber, D., & Anderson, R. (2010). Strength through cultural diversity: developing and teaching a diversity course. College Teaching, 47(3), 107–113.

Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. McGraw Hill.

Human, L. (2005). Diversity management for business success. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

Humberd, B. K., Clair, J. A., & Creary, S. J. (2015). In our own backyard: when a less inclusive community challenges organizational inclusion, equality diversity inclusion. An International Journal, 34(5), 395–421.

Humphrey, N., Bartolo, P., Ale, P., Calleja, C., Hofsaess, T., Janikofa, V., Lous, M., Vilkiene, V. and Westo, G. (2006), “Understanding and responding to diversity in the primary classroom: an international study”. European Journal of Teacher Education, 29(3), 305–313.

Jain, H. (1998), “Efficiency and equity in employment- equity/affirmative action program in Canada, USA, UK, South Africa, Malaysia and India in developing competitiveness and social justice”, 11 th world congress proceedings, Bologne.

Jansen, W. S., Otten, S., Van der Zee, K. I., & Jans, L. (2014). Inclusion: Conceptualization and measurement. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(4), 370–385.

Janssens, M., & Zanoni, P. (2014). Alternative diversity management: Organizational practices fostering ethnic equality at work. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(3), 317–331.

Jonsen, K., Maznevski, M. L., & Schneider, S. C. (2011). Diversity and its not so diverse literature: An international perspective. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 11(1), 35–62.

Joshi, A., Neely, B., Emrich, C., Griffiths, D., & George, G. (2015). Gender research in AMJ: An overview of five decades of empirical research and calls to action. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1459–1475.

King, E. B., Dawson, J. F., West, M. A., Gilrane, V. L., Peddie, C. I., & Bastin, L. (2011). Why organizational and community diversity matter: Representativeness and the emergence of incivility and organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1103–1118.

Kirton, G., & Greene, A. (2010). The dynamics of managing diversity. Oxford: A Critical Approach, Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann.

Kristensen, N., & Johansson, E. (2008). New evidence on cross-country differences in job satisfaction using anchoring vignettes. Labour Economics, 15(19), 96–117.

Kundu, S. C. (2001). Managing cross- cultural diversity: A challenge for present and future organizations. Delhi Business Review, 2(2), 1–8.

Kundu, S. C., & Mor, A. (2017). Workforce diversity and organizational performance: A study of IT industry in India. Employee Relations, 39(2), 160–183.

Larkin, M. B., Bernardi, R. A., & Bosco, S. M. (2012). Board gender diversity, corporate reputation and market performance. International Journal of Banking and Finance, 9(1), 1–27.

Lirio, P., Lee, M. D., Williams, M. L., Haugen, L. K., & Kossek, E. E. (2008). The inclusion challenge with reduced-load professionals: The role of the manager. Human Resource Management, 47(3), 443–461.

Madera, J. M., Dawson, M., & Neal, J. A. (2013). Hotel managers’ perceived diversity climate and job satisfaction: The mediating effects of role ambiguity and conflict. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 28–34.

Miles, J., & Shevlin, M. (2001). Applying regression and correlation: A guide for students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mor Barak, M. E. (2000). Beyond affirmative action: Toward a model of diversity and organizational inclusion. Administration in Social Work, 23(3/4), 47–68.

Mor Barak, M. E., Cherin, D. A., & Berkman, S. (1998). Organizational and personal dimensions in diversity climate ethnic and gender differences in employee perceptions. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 34(1), 82–104.

Morphet, J. (2008). Modern local government. London: Sage Publications.

Mousa, M. (2017). How do nurses perceive their cultural diversity? An exploratory case study. African journal of business management, 11(17). 446–455.

Mousa, M. (2018). The effect of cultural diversity challenges on organizational cynicism dimensions: A study from Egypt. Journal of Global Responsibility, 9(3), 280–300.

Mousa, M. (2018a). Inspiring work-life balance: Responsible leadership among female pharmacists in the Egyptian health sector. Entrepreneurial business and economics review 6(1). 71–90.

Mousa, M. (2018b) “The effect of cultural diversity challenges on organizational cynicism dimensions: A study from Egypt”, Journal of Global Responsibility, 9(3). 133–155.

Mousa, M., & Alas, R. (2016). Cultural diversity and organizational commitment: a study on teachers of primary public schools in Menoufia (Egypt). International Business Research, 9(7), 154–163.

Mousa, M., & Puhakka, V. (2019). Inspiring organizational commitment: responsible leadership and organizational inclusion in the egyptian health care sector. Journal of Management Development, 38(3), 208–224.

Mousa, M., & Ayoubi, R. (2019a). Inclusive/exclusive talent management, responsible leadership and organizational downsizing: A study among academics in Egyptian business schools. Journal of Management Development, 38(2), 87–104.

Mousa, M., & Ayoubi, R. (2019b). Talent management practices: A study on academic in Egyptian public business schools. Journal of Management Development, 38(10), 833–846.

Mousa, M.; Massoud, H. & Ayoubi, R.M. (2020a). Gender, diversity management perceptions, workplace happiness and organizational citizenship behaviour. Employee relations. In press.

Mousa, M.; Massoud, H.; Ayoubi, R.M. & Puhakka, V. (2020b). Barriers of organizational inclusion: a study among academics in Egyptian public business schools. Human systems management, Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 251–263. Scopus.

Nishii, L. (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender diverse groups. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1754–1774.

Nishii, L. H., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader – Member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1412–1426.

Oslen, J. E., & Martins, L. L. (2012). Understanding organizational diversity management programs: a theoretical framework and directions for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1168–1187.

Ozgener, S. (2008). Diversity management and demographic differences-based discrimination: The case of Turkish manufacturing industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(3), 621–631.

Paauwe, J., Guest, D. E., & Wright, P. M. (Eds.). (2013). HRM and performance. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Chichester: Achievements and Challenges.

Perrault, E. (2015). Why does board gender diversity matter and how do we get there? The role of shareholder activism in deinstitutionalizing old boys’ networks. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(1), 149–165.

Pless, N. M., & Maak, T. (2004). Building an inclusive diversity culture: Principles, processes and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 54(2), 129–147.

Ravazzani, S. (2016). Understanding approaches to managing diversity in the workplace: an empirical investigation in Italy. Equality Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 35(2), 154–168.

Richard, O. C., & Johnson, N. (2001). Understanding the impact of human resource diversity practices on firm performance. Journal of Managerial Issues, 13(2), 177–196.

Roberson, Q.M. (2006), “Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations”. Group & Organization Management, 31(2), 212–236.

Romer, P. (1990), Endogenous technological change: national bureau of economic research. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 71–102.

Roosevelt Thomas, R. (1990). From affirmative action to affirming diversity. Harvard Business Review, 68(2), 107–117.

Selden, S. C., & Selden, F. (2001). Rethinking diversity in public organizations for the 21st century moving toward a multicultural model. Administration and Society, 33(3), 303–329.

Seligman, M. C., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: a review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262–1289.

Simons, G. F. (Ed.). (2002). EuroDiversity. A business guide to managing differences. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Smith, N., Smith, V., & Verner, M. (2005). Do women in top management affect firm performance? A panel study of 2500 Danish firms. In Discussion papers no. 03. Copenhagen: Centre for Industrial Economics, University of Copenhagen.

Solakoglu, M. N., & Demir, N. (2016). The role of firm characteristics on the relationship between gender diversity and firm performance. Management Decision, 54(6), 1407–1419.

Su, X., Johnson, J., & Bozeman, B. (2015). Gender diversity strategy in academic departments: exploring organizational determinants. Higher Education, 69, 839–858.

Tang, N., Zheng, X., & Chen, C. (2017). Managing Chinese diverse workforce: toward a theory of organizational inclusion. Nankai Business Review, 8(1), 39–56.

Tereza, M., & Fleury, L. (1999). The management of cultural diversity: lessons from Brazilian companies. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 99(3).

Thomas, R. R. (1991). Beyond race and gender: unleashing the power of your total work force by managing diversity. New York, NY: Amacon.

Van de Voorde, K., Paauwe, J., & Van Veldhoven, M. (2012). Employee well-being and the HRM-organizational performance relationship: a review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(4), 391–407.

van Dijk, H., van Engen, M. and Paauwe, J. (2012), “Reframing the business case for diversity: a values and virtues perspective”. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(1), 73–84.

Vanderbroeck, P. & Wasserfallen, J.B. (2017). Managing gender diversity in healthcare: getting it right. Leadership in Health Services, 30(1), 92–100.

Vuuren, H., Westhuizen, P., & Walt, V. (2012). The management of diversity in schools – a balancing act. International Journal of Education Development, 32, 155–162.

Wah, L. (1999). Diversity at Allstate. Management Review, 88(7), 24–30.

Weimann, J., Knabe, A., & Schöb, R. (2015). Measuring happiness: The economics of well-being. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wikina, S. B. (2011). “Diversity and inclusion in the information technology industry: Relating perceptions and expectations to demographic dimensions”, unpublished doctoral dissertation. Terre Haute, IN: Indiana State University.

Windscheid, L., Bowes-Sperry, L., Jonsen, K., & Morner, M. (2018). Managing organizational gender diversity images: a content analysis of German corporate websites. Journal of Business Ethics, 152, 997–103.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., & Ilies, R. (2012). Everyday working life: Explaining within-person fluctuations in employee well-being. Human Relations, 65(9), 1051–1069.

Zelenski, J. M., Murphy, S. A., & Jenkins, D. A. (2008). The happy-productive worker thesis revisited. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(4), 521–537.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

I hereby assert that my paper has not any conflict of interest.

Funding Information

There is no fund for this paper.

Informed Consent

We hereby certify that no informed consent is applicable to this paper.

Approval

This article does not contain any studies on animals performed by any of the authors. Consent was obtained from all individual participants for participating in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mousa, M. Does Gender Diversity Affect Workplace Happiness for Academics? The Role of Diversity Management and Organizational Inclusion. Public Organiz Rev 21, 119–135 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-020-00479-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-020-00479-0