Abstract

This paper critically scrutinizes the key success factors and tools described in the partnering literature by exploring how they are implemented in a public–private partnering collaboration. In addition to this the paper investigates to what extent these tools facilitate the relationship between the parties in a partnering process. The empirical data consist of two longitudinal case studies. Both cases are large and complex urban development projects in the Swedish water and sewage industry. The results from the cases were ambiguous and positive; as well, some negative outcomes were present. Further, the processes were in both cases far from easy and it required a lot of effort from the parties in the collaboration to make the collaboration work and establish a culture based on trust, especially higher up in the organization. As could be expected, the reality is thus far more complex and cumbersome than previous studies indicate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In constantly and fast changing environments where we face environmental, political as well as economic challenges the importance of putting once strengths together to aim for the best of society has become evidently important. One fruitful way of uniting different interests and resources is through the creation of partnerships where different stakeholders can join for the common good. Partnerships can exist at global, national as well as local levels, and face different types of problems and complexities (Farazmand 2004).

Especially in the public sector at the local government level public sector organizations have long searched for and tried out new solutions for how to best provide public services (Vangen and Huxham 2003; van Meerkerk,, and Edelenbos 2014). For some public organizations the solution has been to collaborate with private sector corporations in partnering constellations (Hilvert and Swindell 2013). Within this context partnering as a phenomenon emerged in the private sector, where it was developed as a reaction to problems experienced in the construction industry (Liu and Wilkinson 2011). As construction projects grew in terms of size and complexity, it became more difficult to specify activities, outcomes and costs in a contract prior to the start of the project (Naoum 2003; Eriksson and Westerberg 2011). As a result, costly conflicts due to difficulties in meeting the client criteria as well as mistrust between the purchaser and the provider grew in number (Naoum 2003; Chan et al. 2004). Emphasizing collaboration by introducing the concept of partnering, the hope was to solve the problems experienced.

There is no one definition for partnering; however, the phenomenon is generally described in the literature as a form of collaboration between two or more parties. The focal points of the collaboration are the creation of a culture characterized by trust, and problem solving based on shared goals and mutual dependency (Naoum 2003; Gadde and Dubois 2010). This goes moreover in line with the more overarching concept of partnership described by Farazmand (2004) as including the essence of “sharing power, responsibility and achievements” (Farazmand 2004:81). When being in a collaboration the intention is that all parties contribute and benefit from the relationship (Hilvert and Swindell 2013). Partnering becomes in this way one form of a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) where collaboration is emphasised. But also other forms of PPPs exists, for example the more contract-based relationship which does not emphasise that all parties contribute equal to the project (Hilvert and Swindell 2013).

To base a relationship on collaboration and mutual trust seems ideal, especially when considering the issues often mentioned in relation to PPP regarding, among other things, mission drift and problems with securing accountability and goal alignment (Osborne 2000; Sands 2006; Shaoul et al. 2012; Vining and Weimer 2016). These are outcomes not reported in the literature on partnering. Instead the literature on partnering provides us with key success factors and tools for how to achieve the partnering culture (see, for example, Ng et al. 2002; Bayliss et al. 2004; Eriksson 2010). There is also an apparent tendency in the literature on partnering to emphasize the positive aspects of partnering and the successful outcomes and to downplay how challenging it is to establish a culture (Kadefors 2004; Bresnen 2007; Gadde and Dubois 2010). A possible explanation of this tendency is that only projects with a positive outcome have been studied, combined with the fact that managers when looking back on a project tend, and perhaps naturally so, to overemphasize the positive and downplay the negative aspects (Hilvert and Swindell 2013). Another aspect to consider is that several of the studies focusing on partnering as a form of collaboration have been conducted in the private sector. Consequently, the results from these studies are not necessarily applicable to situations when partnering is used in public–private collaboration.

As partnering becomes more frequently used within the public sector, it is of interest to go into more depth as to how partnering actually works in a public sector context. It is also of interest to critically scrutinize the ability to apply the partnering toolbox as presented in the literature to actually create a partnering culture and commitment to the philosophy of partnering. This should be especially valuable considering the problems reported in earlier studies concerning mission drift and goal conflict in different types of PPP (Shaoul et al. 2012; Sands 2006; Watson 2003). Hence, the purpose of this study is to critically scrutinize the key success factors and tools described in the partnering literature by exploring how they are implemented in construction projects based on public–private partnering collaboration and to investigate to what extent these tools facilitate the relationship between the parties in a partnering process. The focus is thus here not on PPP in general, but on the specific type of collaboration called partnering.

In order to fulfil the purpose, two longitudinal case studies of partnering processes were conducted where collaboration has been established in accordance with recommendations drawn from the partnering literature. Both cases are large and complex urban development projects in the water and sewage industry. The results of these case studies have been analysed and compared to a framework based on the key success factors and tools as presented in the partnering literature. With this approach, our aim is to provide a more nuanced picture of partnering as well as to explore the pitfalls, drawbacks and benefits of partnering and how it can be used by public sector organizations to solve complex problems and lack of access to scarce resources.

In the next section, the concept of partnering is more thoroughly defined and the toolbox and key success factors associated with partnering are presented. This material will be used as a backdrop for analysing the implementation of partnering in the two case studies. The third section of the paper presents the method and the cases selected for the study. This is followed by a presentation of the results of the case studies, a discussion of the results and the practical implications of the study and suggestions for future research.

Partnership and Partnering

The benefits of collaboration is nothing new and has long been emphasised as of importance value for the public good (e.g. Farazmand (2004, 2007). Identified benefits are that partnerships promote creativity, it creates involvement among a broader set of stakeholders, it strengthen the relation between included parties, and it can lead to more effective governance as it open up for good learning possibilities. Due to the diversity of partnerships, regarding level (global, national, local) type of stakeholders (NGOs, stage, government, corporations, citizens) and aims, there is a multitude of partnership strategies as well as partnership models. (Farazmand 2004).

The form of collaboration we focus on in this paper is at the local government level and the partnership form goes under the term partnering. Partnering is generally described as a form of collaboration with the purpose of improving project performance (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Eriksson 2010) and has its roots in the development of strategic alliances and was developed further within the construction industry in Great Britain, the United States, and Australia (Naoum 2003). Even though the general perception of partnering is that it is a form of collaboration, a clear definition of the concept is lacking.

Previous research on the subject provides us with different types of definitions (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Bygballe et al. 2010; Eriksson 2010). The general view, however, seems to be that partnering is an inter-organizational form of collaboration (a partnering organization is formed by gathering employees from the organizations involved in the partnering process) focusing on trust, openness, joint objectives, mutual commitment and problem solving (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Eriksson 2010; Gadde and Dubois 2010). The values described herein are often referred to as the philosophy of partnering, and it is this philosophy that sets partnering apart from the traditional contractual relations (Naoum 2003). Partnering is thus viewed as leading to an adaptation of the customers’ needs, increased quality, efficiency and potential to save time and costs (Black et al. 2000; Cheung et al. 2003; Gadde and Dubois 2010; Eriksson and Westerberg 2011).

Partnering - Implementation and Key Success Factors

The challenge of partnering is the implementation of the form and ability to build the culture based on trust, which is necessary for establishing collaboration (Ng et al. 2002; Eriksson 2010; Gadde and Dubois 2010). To take the philosophy of partnering and convert it into managerial practice is likewise challenging (Gadde and Dubois 2010). Previous studies on partnering highlight the aspects necessary for a partnering process to be successful, that is, the key success factors of partnering (Cheung et al. 2003; Bayliss et al. 2004; Chan et al. 2004; Kadefors 2004). The factors most frequently highlighted are: creating common goals; overcoming cultural differences; working across organizational boundaries; securing equal commitment from all the parties involved, including all the stakeholders; and establishing forms of communication as well as roles (Black et al. 2000; Ng et al. 2002; Naoum 2003; Chan et al. 2004; Gadde and Dubois 2010).

More specifically, challenges exist in the implementation of a culture and creating the values of trust and mutual commitment that constitute the essence of the partnering collaboration (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Kadefors 2004; Gadde and Dubois). The more critical studies of the partnering process highlight these difficulties as well as the tendency to assume that the outcome of the process will be positive, without recognizing the time and effort it takes to create a culture and instill values (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Kadefors 2004; Gadde and Dubois 2010). Often, it takes more than one project to establish trust and shared values. According to Bayliss et al. (2004), trust is built through problem solving and crisis management during which the relationship between the collaborating parties is tested. The fact that partnering requires time and effort indicates that it is not a form suitable for all types of projects and situations (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a: Bayliss et al. 2004). Even though the problems and challenges of partnering are recognized and discussed, only a small number of empirical studies have gone into depth to look at the process of implementing partnering for collaboration.

Partnering – Tools for a Successful Implementation

Nonetheless, the literature does provide a set of tools to establish a culture in accordance with the partnering philosophy. Examples often mentioned include: workshops (at the beginning and end of a project), preparation of the employees, evaluations and benchmarking throughout the project by all of the parties involved, regular meetings, quick response to problems, and working with open books when it comes to financial reporting (Ng et al. 2002; Bayliss et al. 2004; Eriksson 2010). The workshops at the beginning of a project and the preparation of employees are highlighted as important to align the goals and establish a culture based on the partnering philosophy (Black et al. 2000; Chan et al. 2003).

The mere use of the suggested tools, however, does not guarantee a successful implementation of partnering. More critical researchers of partnering such as Bresnen and Marshall (2000a) and Kadefors (2004) as well as Gadde and Dubois (2010) stress the difficulty in creating a culture and the fact that such processes take time. Bresnen and Marshall (2000a), for example, identify the need for a deeper understanding of the motivation of individuals as well as the complexity of the group dynamics. Kadefors (2004) argues along the same lines, but in terms of how trust is built in relationships, she stresses the need to consider behavioural aspects in human relations when building a culture based on trust. For similar reasons, it is regarded as difficult to develop incentives that support cultural development along the lines of the partnering philosophy. According to Kadefors (2004), as well as Bresnen and Marshall (2000b), there is a risk in relying too heavily on economic incentives since such incentives could turn the focus away from collaboration and the pursuit of shared goals.

To summarize, what sets partnering apart from a traditional contractual relationship is the focus on collaboration and trust in the relationship between the purchaser and the provider. Focus is thus shifted from the content of the contract to the relationship and mutual dependency between the parties involved in the management of projects and contracts.

Culture, however, is a difficult phenomenon to capture in a study (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Kadefors 2004). Hence, it is also difficult to focus only on the extent to which a culture with a certain set of values has been established (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Kadefors 2004). Therefore, the point of attention in this paper is how partnering is implemented and used in the two cases studied. As a way to approach an analysis of the implementation process, the backdrop of the study will be the use of key success factors and tools described in the research on partnering, which are summarized in Table 1 below.

Method

The explorative nature of this study called for the use of a qualitative case study (Bryman and Bell 2003; Eisenhardt 1989). The case study method was also chosen because it supports analytical generalization and theory development (Eisenhardt 1989; Yin 2003); and it is in line with the main purpose of the study, to explore the applicability of partnering in a public sector context with focus on large and complex urban development projects. The case studies are longitudinal; this approach can overcome some of the weaknesses of previous studies, particularly the tendency for managers, when looking back, to forget bad experiences and emphasize the good ones (Hilvert and Swindell 2013). To counteract this tendency, the researchers followed the partnering process and how it developed over time; on a regular basis during the process, they met with and interviewed the managers, attended workshops, visited the site, attended benchmarking meetings, took part of different documents related to the partnering projects. In this way, the researchers hoped to capture the experiences as they occurred and before they fell into oblivion.

Selection of Cases

Two cases of partnering were chosen for the study. The researchers felt that the use of two cases would strengthen the results, since this would allow for a comparative study of the applicability of the partnering literature and thus reduce the vulnerability of the study (Yin 2003).

The first case was a development project in a municipality within the Stockholm region of Österåker, and the second was a development project in the north of Sweden in the town of Sundsvall. In Sweden, water and sewage services fall within the responsibility of each municipality; thus, the project owners in both Österåker and Sundsvall were a water and sewage company owned by the respective municipality. Since the two cases had similar characteristics, similar results were expected from the case studies, which is what Yin (2003) refers to as literal replication.

For both cases, the empirical material was mainly gathered through semi-structured interviews with representatives from the project owner and the project partner. The material from the interviews was supplemented by documents and observations of benchmarking meetings, workshops and other meetings related to the project. For the Österåker project, the interviews were conducted on six different occasions during the project, a total of 23 interviews. For the Sundsvall project, the interviews were conducted on three different occasions, a total of 13 interviews. In addition to the interviews, observations were made during two workshops in the Österåker project and one benchmarking meeting in both the Österåker and the Sundsvall projects. By the last round of interviews there were signs of the study having reached saturation in terms of data, since the interviewees were then revealing no new information. The material from the interviews and the workshops was transcribed and then analysed based on the themes from the framework. First, each case was analysed separately, and then a comparative analysis was conducted. The results of the analyses are presented in the following section.

Results

This results section begins with a presentation of the two cases. Thereafter, the results regarding the implementation process, the tools used, and the outcomes experienced are discussed.

Background and Motives behind Partnering

The partnering projects in both Sundsvall and Österåker were large development projects, in each case the conversion of a summer housing area into a residential area. The conversion increased the load on the existing water and sewage infrastructure, so that there was a need to expand and develop the capacity of the existing infrastructure. Consequently, the municipality-owned water and sewage companies in Sundsvall and Österåker, respectively, were assigned by the elected municipal politicians to plan, procure, and carry out the projects. Also, in both Sundsvall and Österåker, the development of the areas was not restricted to the infrastructure of water and sewage; it included plans for building walkways, bike lanes, and roads. As a result, it was not only the municipal water and sewage company that was also involved in the projects, but other parts of the municipal organization.

After the municipal water and sewage company in Österåker was assigned to manage the development project, it initiated a public procurement from which three candidates were selected; after negotiations with the three parties, one large construction company was selected. Due to the complexity and scope of the project, partnering was the chosen form of development. Conducting a traditional contracting process was viewed as being more time-consuming; in addition, it would increase the duration of the project and thus the length of time that the area’s citizens would be affected by the construction. The project was initiated in 2008, and the goal was for the work relating to the water and sewage to be completed before the general elections in 2014. This goal was fulfilled. Some of the work on walkways, bike lanes, and roads remains to be completed in 2015.

As in Österåker, the project in Sundsvall was complex and large; it affected or involved several groups of stakeholders and was thus difficult to plan and specify in a contract. The process was initiated in early spring 2010 with a public procurement; through the selection process following the call for tender a large construction company (not the same as in Österåker) was chosen as a partner. By the end of 2010, the project was up and running and a majority of the project activities were finished in advance of the project schedule, with the whole project being completed in 2015.

Implementation and Key Success Factors

In both Österåker and Sundsvall, the projects were governed by a project organization consisting of a steering group and a project management group. Each of these latter groups comprised members from the municipal company as well as the construction company. The difference was that in Österåker, the municipality was part of the project organization, and this was not the case in Sundsvall.

The steering groups were responsible for the strategic issues, while the project management groups were responsible for the daily management of the projects. The project management group consisted of the project managers; however, in Österåker it also included representatives from the three main stakeholders. The project management groups reported to the steering groups about the progress of the project, in terms of activities and budget. Below these two groups were the project organizations, consisting of employees from the municipality and the construction company who worked onsite. In both cases, the administrative support was provided by the municipal company and the main municipal organization itself. At all levels, regular meetings took place during which the progress of the project was reported, discussed, and evaluated.

One important aspect in the implementation process was how the stakeholders involved in or affected by the project were included in the process as well as informed about the project. This has been emphasized as one of the key success factors in previous studies of partnering (Black et al. 2000; Ng et al. 2002; Naoum 2003; Chan et al. 2004). Perhaps the most important stakeholder in both of the cases, from the municipal company’s point of view, was the project partner, i.e., the construction firm. In order to manage the collaboration with the project partner, the relationship and the terms for the collaboration were taken into consideration in both cases, during the design of the project organization as well as when negotiating the terms of the contract and establishing routines for the project (meetings, forms of communication, flow of information, etc.). Reports from the researchers’ interviews account for how the relationship between the project owner and the project partner improved over time as the partners got to know each other. This was especially true in the case of Sundsvall, in terms of how problems that surfaced during the project were solved in collaboration with the parties involved. This was pointed out as crucial for the development of trust and goal alignment. In the case of Österåker, it was the importance of the relationship between individuals that was stressed.

Trust, goal alignment, and collaboration are highlighted in the literature as essential parts of the partnering philosophy. However, the cases confirm that trust is not something that you can expect at the beginning of the process, as is sometimes alluded to in partnering studies. Rather, it is something that is established over time through daily collaboration and crisis management, as pointed out in studies that have adopted a more critical perspective in their analysis of partnering projects (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Kadefors 2004; Gadde and Dubois 2010).

One of the stakeholders often mentioned in both cases was the municipality. In relation to the municipalities, there was one interesting difference between the cases: that is, the design of the partnering organization. In Österåker, the municipality was initially included in the partnering organization. The argument supporting this was that the municipality was an important player because the project was dependent on the municipality. This was so, not only because the establishment of other types of infrastructure was included in the project, but also because the municipality was the local authority having control over land and land development as well as providing building permits.

The degree of involvement of both the municipalities was to a large extent similar. Nevertheless, in Sundsvall the decision was made during the implementation of the partnering form not to include the municipality in the partnering organization. Furthermore, during the whole project, the view from the perspective of the municipality was that it was a water and sewage specific project rather than a large development project that affected several areas of the municipal organization. However, in Österåker even though the municipality was included in the partnering organization, similar experiences were reported from that case. The overall experience, however, was more positive in Österåker even though the municipality and the municipal corporation did not see eye to eye in all of the issues; the understanding between the other parties and their situation improved as representatives from different organizations got to know each other. The increased understanding and insight into each other’s work processes was something that was regarded as being useful for future projects when the municipality and the municipal corporation might need to collaborate.

Another group of stakeholders often mentioned in both cases were the citizens – specifically, those households affected by the infrastructural development within the geographical area of the projects. In both cases, the respondents expressed the importance of keeping the citizens informed about the project. In Sundsvall, the need to legitimize the project was perhaps more extensive than in the case of Österåker, since several of the citizens affected by the development were negative towards paying the connection fee and did not see the need for municipal water and sewage, while in the case of Österåker the attitudes towards the development project were more positive.

Other key success factors mentioned in the literature as being of importance for the success of a partnering project were: creating common goals, overcoming cultural differences, working across organizational boundaries, securing equal commitment from all the parties involved, and establishing forms of communication and roles (Black et al. 2000; Ng et al. 2002; Naoum 2003; Chan et al. 2004; Gadde and Dubois 2010). None of these factors can be regarded in isolation from each other, since they to a large extent influence and reinforce each other. Important aspects in the implementation process in both case studies have been the design of the project organizations and the routines established for meetings, flow of information and communication among the parties.

In both cases, the design of the project organization was important in order to secure the development of a shared culture and to ensure that collaboration and work occurred across organizational boundaries. This was especially noticeable at the lower levels of the project organizations, i.e., the project managers and those employees working at the site. At that level, the common working culture developed so strongly that the employees identified themselves more with the project organization than with their employer, a development that occurred early on in the project. This was especially true for the case in Sundsvall. The fact that the culture of the project organizations became so strong could perhaps partly be explained by the working conditions of the construction industry. The employees of these companies are used to being employed on a project basis and thus never develop a deeper loyalty towards the companies they work for. It could also be explained by having the preparation sessions for the employees, including the workshop held at the beginning of both projects and the fact that at this level of the project organization, the employees shared a common workplace and had to collaborate on a daily basis.

Higher up in the project organization, more specifically at the level of the steering group, it took much longer before a culture of mutual commitment and trust as well as goal alignment was established. One reason could be that since this group consisted of managers from the partnering organizations, they did not meet on a regular basis and did not work in the same organizations. Also, at this level the different interests and goals of the partnering organizations became apparent, since it was at this level that the strategic goals of the project were discussed and evaluated. Trust was developed over time, as problems emerged that needed to be solved in collaboration, resulting in the parties learning to rely on each other. In Sundsvall, the CEO of the municipal company stressed during an interview how the relationship had developed over time and the fact that at the end of the project the relationship was strong, adding that it was almost sad that the project came to an end. The CEO attributed the strong relationship between the parties to the issues of costs and the external critique of the project that they had been forced to deal with halfway through the project. This supports the results from previous studies, which found that crises are the foundation for strong relationships and that partnering is really beneficial when collaborations occur on more than one occasion with the same partner (Cheung et al. 2003).

The Tools Used

In the two cases studied, all the tools accounted for in the literature (as summarized in Table 1) were used, with only one exception: that was the use of open books in the case of Österåker, where there was a discussion regarding how to calculate and estimate costs). However, it is difficult to assess the extent to which the use of the tools contributed to implementing the core values of the partnering philosophy. One interesting aspect to highlight, however, is the use of the workshops. The workshops held at the beginning of the project were regarded in both cases as being of importance for the establishment of a shared culture, and in that aspect this study supports previous research on partnering (Black et al. 2000; Chan et al. 2003).

Further, the budget was regarded as an important tool. Also discussed positively were the routines for flow of information and the importance of good communication between the project management team and the steering committee, in order to provide the steering committee with the information necessary to evaluate the progress of the project. Similar issues were discussed in both cases but not to the same extent in Österåker. There, the role of the project manager surfaced as being important for the project. Thus, it seems like some tools were paid more attention than others.

Another interesting aspect was the reported difficulty in establishing incentive systems for the partnering projects. In both cases, efforts were made during the start of the projects to establish a system of incentives for the project partner. The systems developed at the beginning of the projects, however, were abandoned in both cases after a while. The explanation given for this was the difficulty in developing incentive systems that were in line with and which supported the partnering philosophy on collaboration. This is in accordance with the results from previous studies pointing towards the difficulty in finding appropriate incentive systems for partnering (Bresnen and Marshall 2000b).

Experiences and Outcomes from Partnering

The general experiences from the two cases of partnering studied were positive, but the outcome was a mix of positive and negative results. The downside was that in both cases the projects turned out to be more expensive than estimated. To decide on a budget in advance, however, is not in line with the idea of partnering, which is to avoid the focus on costs in favour of a focus on quality and customer adaptation (Larsson 1997).

In the literature on partnering, partnering is regarded as a way to lower the costs of a project through collaboration and by focusing on problem solving (Black et al. 2000; Naoum 2003; Cheung et al. 2003; Eriksson and Westerberg 2011). It is impossible to determine the extent to which the actual costs of the projects studied herein were higher or lower than the costs that would have been incurred if a traditional contract approach had been used, since we have nothing to compare with. The only point of reference is the early estimates; both projects turned out to be much more expensive than first predicted.

One explanation as to why the costs turned out to be higher than expected was that the process was more difficult than previously estimated. In Sundsvall, it was difficult to assess the geological conditions in advance, and in Österåker, besides the geological conditions, there was also an issue with getting permits to exploit the area, which proved to be difficult and time-consuming. The difficulties in assessing the full scope of the project and the potential problems in advance were the reason for why the partnering model was chosen, which is also the reason why partnering should be used, according to the literature. Thus, focusing on the costs in that context departs from the purpose of the form. Also, decisions were made during the project in both cases to prioritize and take into consideration as well as accommodate the needs and conveniences of the citizens. One example of that was the effort to replace the original roads that were destroyed in the process with temporary roads. Another example was that when the roads were rebuilt, other infrastructural work, which was needed, was done at the same time in order to avoid the extra inconvenience. The ability to adapt to customer preferences is one of the advantages of the partnering form (Larsson 1997), but being overly flexible could have contributed to the increase in the costs of the projects.

Another experience that was reported in both cases related to knowledge transfer and learning. Both municipal companies attributed an increase in their knowledge of project management to what was gained through the collaboration with the contract company. Other areas where knowledge transfer was reported was in relation to the environmental issues and construction techniques. Knowledge transfer has been mentioned by some as researchers as a positive effect of partnering (Bayliss et al. 2004; Bygballe et al. 2010), but there has been no elaboration or evidence presented of this in the literature on partnering.

Discussion

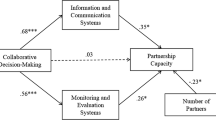

The purpose of this study was to critically scrutinize the key success factors and tools described in the partnering literature by exploring how they are implemented in projects based on public–private partnering collaboration. In order to respond to the purpose, the results of the study will now be discussed by using the key success factors and tools and the summary of previous research presented in Table 1 as a backdrop. Consequently, when the results of the study are discussed in detail, Table 1 will be revisited in Table 2, where the results from the case studies are presented in bold.

Several factors highlighted in previous studies as key success factors or potential outcomes also turned out to be of importance in the cases reported in this paper. One example is the importance of including all the stakeholders involved in the project in the partnering organization (Ng et al. 2002; Chan et al. 2004). This conclusion also supports the research findings that partnering and the outcome of partnering depends on the process and the case at hand (Eriksson 2010), since it was the differences in the process between the cases that made this apparent. Furthermore, the need to establish ways of communication and roles turned out to be important in both cases.

The case studies also illustrate the difficulty in developing incentive systems that support the partnering philosophy as well as the need to look at the differences in the conditions for establishing a partnering culture that might exist on different levels in the partnering organization. Previous studies that use a more critical perspective on partnering (Bresnen 2007) point to the difficulty in implementing a culture in the organizations as well as the importance of taking into consideration social interaction and individual values (Bresnen 2007). In the cases studied herein, the consideration of such aspects has not been mentioned. However, it is possible that the positive working environment that was established at the project site was influenced by factors other than just the initial workshop; in other words, there were more intangible processes taking place among the employees sharing the challenges of everyday work on the site. What this study also confirms is the difficulty in developing and implementing incentive systems that support the partnering culture (Bresnen and Marshall 2000b; Kadefors 2004).

Perhaps more interesting are the differences in the results from this study and the previous studies. One such difference is the process of developing a partnering culture. While a partnering culture was developed almost from the beginning in the project organization, it took a longer time for the same culture of trust to be established among the parties in the steering committee. This difference in the degree of culture implementation is not mentioned in previous studies of partnering and hence is one of the contributions of this study.

Another interesting aspect that surfaced during the analysis of the cases was the discussion regarding the trade-offs between the goals, resources and deadlines, which took place in both cases. This occurred despite the fact that the purpose of using partnering as a form is to avoid short-term focus on costs and instead focus on quality and long-term goals (Larsson 1997; Black et al. 2000; Eriksson and Westerberg 2011). One reason why this discussion surfaced can be found in the public sector context and the democratic process. In both cases, the politicians had established the goals for the project in terms of deadline (in the case of Österåker) and regarding the budget (in both cases). Local politicians in Sweden are elected for a period of four years and are to be held accountable by the end of their term. Large projects such as the ones studied here attract a lot of attention from the citizens as well as the media; therefore, it is in line with the interests of the politicians to be able to show good results. Based on this and the results from the case studies, therefore, it is likely that the public sector context had an impact on the implementation of partnering.

The fact that the context is of relevance is discussed in previous research on partnering and is thus nothing new (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a). What is new, however, is that this study shows the more specific influence from the public sector context – more precisely, the impact of the political process on the longer-term goals that characterize partnering.

Yet another interesting contribution is how the use of partnering enables knowledge sharing and the potential for transferring that knowledge back to the organization once the project comes to an end. The effects on knowledge transfer have not been addressed in previous research, even though it is regarded as one of the benefits of partnering (Bayliss et al. 2004; Bygballe et al. 2010); thus, this is a further contribution of this study. However, Gadde and Dubois (2010) point to the fact that in order to extend the collaboration that occurs between the partnering projects, it would require knowledge transfer and some kind of formal centralized activity that supports such a process. What this study shows is that the tools provided within the definition of partnering might suffice as a support system for knowledge transfer.

Thus, the results from the cases were ambiguous and positive; as well, some negative outcomes were present. Further, the processes were in both cases far from easy and it required a lot of effort from the parties in the collaboration to make the collaboration work and establish a culture based on trust, especially higher up in the organization. As could be expected, the reality is thus far more complex and cumbersome than previous studies indicate.

Concluding Remarks

Due to the in-depth and explorative character of this study, the picture painted herein regarding the partnering process is a more complex and ambiguous one than provided in previous research. The use of the tools and the focus on key success factors when implementing partnering as a form of collaboration might be of support to the parties involved and provide them with some kind of guideline of how to structure the collaboration, but it is far from enough. The process is far more cumbersome than earlier studies indicate. The results from this study show the effort and constant struggle that was required on behalf of the managers in order to keep the focus on the shared goals and to maintain a good relationship with all stakeholders involved. Especially the latter required a lot of attention and this could be partly due to the public sector context, where the political and democratic aspects and the need to secure accountability are central.

Even though partnering is far from the panacea that it sometimes is portrayed to be, partnering has its merits and could work well in a public sector context. It does, however, require determination and focus as well as constant work throughout the process. If partnering is used on a recurring basis and with inter-partner relationships already established, the process might be easier. This is also an aspect mentioned in previous research (Bayliss et al. 2004) and is further indicated by the result from this study that shows how new knowledge emerged and was transferred back to the partnering organizations.

A further notion that has been made is that the results of this study can be linked to wider concept of partnership as discussed in e.g. Farazmand (2004). The studied partnering projects appear to be in line with the positive effects that are stressed in the discussion of partnership and governance, i.e. sharing power, responsibility and achievements. Even though not every citizens know how has increased, the know-how of the municipal corporation has increased and the service to the public is experienced as of high value.

The practical implications of this study is that it provides managers and project owners in the public sector with information on how partnering and the focus on collaboration can be used to establish trust and goal alignment in the contractual process. Vice versa, it provides private organizations with information regarding how to improve collaboration with the public sector organizations.

What needs to be stressed, however, is the influence of the context on the implementation process. Partnering, at least based on the results from this study, seems to be applicable to large and complex development projects. However, this does not mean that partnering is applicable in all types of contracting situations in the public sector. Taking into consideration the specific situation is also stressed in the previous studies of partnering in the private sector (Bresnen and Marshall 2000a; Bayliss et al. 2004).

Due to the explorative nature of this study, however, the goal here was not to make empirical generalizations (Yin 2003; Eisenhardt 1989). Consequently, there is a need to further investigate the use of partnering in a public sector context. For example, it would be of interest to have studies focusing on the use of partnering within the public sector in other countries and for other types of projects and services than those studied here. Another area of interest would be to further explore the impact of the democratic process on the collaboration between the public and private organizations.

References

Bayliss, R., Cheung, S.-O., Suen, H. C. H., & Wong, S.-P. (2004). Effective partnering tools in construction: a case study of MTRC TKE contract 064 in Hong Kong. International Journal of Project Management, 22, 253–263.

Black, C., Akintoye, A., & Fitzgerald, E. (2000). An analysis of success factors and benefits of partnering in construction. International Journal of Project Management, 18, 423–434.

Bresnen, M. (2007). Deconstructing partnering in project-based organization: seven pillars, seven paradoxes and seven deadly sins. International Journal of Project Management, 25, 365–374.

Bresnen, M., & Marshall, N. (2000a). Partnering in construction: a critical review of issues, problems and dilemmas. Construction Management and Economics., 18, 229–237.

Bresnen, M., & Marshall, N. (2000b). Motivation, commitment and the use of incentives in partnerships and alliances. Construction Management Economics., 18, 587–598.

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2003). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bygballe, L. E., Jahre, M., & Swärd, A. (2010). Partnering relationships in construction: a literature review. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 16, 239–253.

Chan, A. P. C., Chan, D. W. M., & Kathy, S. K. H. (2003). Partnering in construction: critical study of problems form implementation. Journal of Management in Engineering, 19, 126–135.

Chan, A. P. C., Chan, D. W. M., Chiang, Y. H., Tang, B. S., Chan, E. H. W., & Kathy, S. K. H. (2004). Exploring critical success factors for partnering in construction projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 130, 188198.

Cheung, S.-O., Ng, T. S. T., Wong, S.-P., & Suen, H. C. H. (2003). Behavioral aspects in construction partnering. International Journal of Project Management, 21, 333–343.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 532–550.

Eriksson, P. E. (2010). Partnering: what is it, when should it be used, and how should it be implemented? Construction Management and Economics, 28, 905–917.

Eriksson, P. E., & Westerberg, M. (2011). Effects of cooperative procurement procedures on construction project performance: a conceptual framework. International Journal of Project Management, 29, 192–208.

Farazmand, A. (2004). Sound Governance: Policy and Administrative Innovations. (Ed. Farazmand, A. ch. 4. Building partnerships for sound governance. A. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Farazmand (2007). Handbook of Globalization, Governance, and Public Administration. Co-editor: Pinkowski, J. NY: Taylor & Francis.

Gadde, L.-E., & Dubois, A. (2010). Partnering in the construction industry-problems and opportunities. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 16, 254–263.

Hilvert, C., & Swindell, D. (2013). Collaborative service delivery: what every local government manager should know. State and Local Government Review, 45(4), 240–254.

Kadefors, A. (2004). Trust in project relationships – inside the black box. International Journal of Project Management, 22, 175–182.

Larsson, E. (1997). Partnering on construction projects: a study of the relationship between partnering activities and project success. Transaction on Engineering Management, 44, 188–195.

Liu, T., & Wilkinson, S. (2011). Adopting innovative procurement techniques – obstacles and drivers for adopting public private partnerships in New Zealand. Construction Innovation, 11, 452–469.

Naoum, S. (2003). An overview into the concept of partnering. International Journal of Project Management, 21, 71–76.

Ng, T., Rose, T. M., Mak, M., & Chen, S. E. (2002). Problematic issues associated with project partnering – the contractor perspective. International Journal of Project Management, 20, 437–449.

Osborne, S. P. (Ed.) (2000). Public-private Partnerhsips: theory and practice in international perspective. New York: Routledge.

Sands, V. (2006). The right to know and obligation to provide: public-private partnerships, public knowledge, public accountability, public disenfranchisement and prison cases. UNSW Law Journal, 29(3), 334–341.

Shaoul, J., Stafford, A., & Stapelton, P. (2012). Accountability and corporate governance of public-private partnerships. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23, 213–229.

van Meerkerk, I., & Edelenbos, J. (2014). The effects of boundary spanners on trust and performance of urban governance networks: findings from survey research on urban development projects in the Netherlands. Policy Sciences, 47, 3–24.

Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2003). Nurturing collaborative relations: building Trust in Interorganizational Collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(5), 5–31.

Vining, A. R., & Weimer, D. L. (2016). The challenges of fractionalized property rights in public-private hybrid organizations: the good, the bad and the ugly. Regulation and Governance, 10, 161–178.

Watson, D. (2003). The rise and rise of public private partnerships: challenges for public accountability. Australian Accounting Review, 13(3), 2–14.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, E.M., Thomasson, A. The Use of the Partnering Concept for Public–Private Collaboration: How Well Does it Really Work?. Public Organiz Rev 18, 191–206 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-016-0368-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-016-0368-9