Abstract

This study examines the relationship between political attitudes, affective polarization, and fertility preferences among married couples in Hong Kong. Using dyadic data from a representative household survey (N = 1586 heterosexually married adults), we investigate how individuals’ attitudes toward democracy and levels of affective polarization are associated with their fertility preferences. We also explore the influence of spouses’ political attitudes and affective polarization on one's fertility preferences. We found that individuals with stronger support for democracy have lower fertility preferences. This negative association between political attitudes and fertility preferences is further amplified by one’s level of affective polarization. The findings of this study contribute to our understanding of how political factors shape fertility patterns in the context of dramatic political transitions. This study provides valuable insights into the complex dynamics between political attitudes, affective polarization, and family formation decisions in Hong Kong, which have both theoretical, policy and political implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

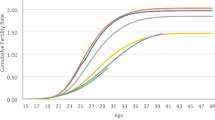

Over the past two decades, total fertility rates in the advanced economies of Asia have been described as “ultra-low,” and their trend is still in decline. Previous studies have identified social and economic factors that contribute to the low fertility rates in Asia against the backdrop of compressed modernity, including the increasing cost of children, work-family conflicts, delayed and declining marriage, and housing problems (Cheung, 2023; Cheng & Hsu, 2020; Jones, 2007; Raymo et al., 2015). Among these advanced economies, Hong Kong’s fertility rate is particularly low, at around 0.70 per women in 2022—the lowest and the fastest in its decline during the COVID pandemic (see Fig. 1). A notable decrease in the TFR was found after 2019 when the year-long Anti-Extradition Amendment Bill movement (or Anti-ELAB) sparked off, and unlike other societies, its TFR has not bounced back after COVID (Gietel-Basten & Chen, 2023). It is hard to ignore the role of politics in fertility decline in the case of Hong Kong. However, there have been only scant discussions in the demographic literature regarding politics as a potential mechanism for changing population dynamics in societies with advanced economies (Teitelbaum, 2015). This study centralizes politics, in particular, people’s political attitudes toward democracy and animosity against opposing political groups (i.e., affective polarization), in shaping fertility preferences. In doing so, we uncover how “personal is political,” especially in times of political transitions.

Hong Kong had long been a semi-democratic polity protected by the Basic Law, a constitutional document that permits a separate sociopolitical system from Mainland China, despite being part of its country. The political camps in Hong Kong are generally divided into pan-democrats and pro-establishment. The former pushed for universal suffrage for the Chief Executive (equivalent to the Head of Government) and the members of the legislature as stipulated in the Basic Law. The latter is pro-government and pro-China, and in general, they are more conservative in their approach to political reforms. The division widened, particularly after the Umbrella Movement in 2014, and it peaked during the Anti-ELAB protests in 2019 (Lee et al., 2019). Affective polarization against different political orientations reached historic highs when contestations between protestors and police officers were fierce (Wu & Shen, 2020). The media, political groups, and participants from both sides make moral accusations against one another (Bhowmik et al., 2023). Social relations became emotionally charged and broke down (Lai, 2023). The aftermath of the Chinese Central Government imposing National Security Law on Hong Kong further antagonized pro-democrats, as this law tightened China’s political control over Hong Kong. It also restricted the eligibility of candidates running for elections. Thereafter, there were massive closedowns on democratic pressure groups and media and large-scale arrests of political leaders and dissidents. These political changes resulted in a dramatic surge in emigration (Kan et al., 2023; Li & Liao, 2023; Lui et al., 2022).

While there is emerging literature investigating how political changes have shaped emigration trends and patterns in Hong Kong (Li & Liao, 2023; Lui et al., 2022), empirical investigations into how the political environment shapes fertility are still limited. An exception is the recent research by Gietel-Basten and Chen’s (2023), who analyzed monthly fertility time-series data and noted that the recent fertility decline is attributed to different birthplaces, assuming them to be an indicator of political orientations. Despite their attempt, birthplace alone does not directly measure political orientations. Thus, despite their contribution to understanding the potential role of politics in fertility, the relationship between political orientations and fertility remains unclear. We argue that it is crucial to understand whether individuals with strong support for democracy may exhibit lower fertility preferences, as recent political changes might have created a depressing environment for them. Furthermore, it is yet to find out how political emotions come into play. To date, no existing studies have examined the potential roles of partners’ political attitudes and affective polarization in shaping one’s fertility preference.

In this study, we aim to investigate how couples with different political attitudes toward democracy and feelings toward supporters of political out-groups differ in their fertility preferences. Recognizing that fertility decisions are usually made consensually and collectively by couples, we will also disentangle how the spouse’s political attitudes and affects shape one’s fertility preferences. Specifically, we ask the following questions: (1) Are people’s political attitudes toward democracy and affective polarization associated with their fertility preferences? (2) Do these attitudes and affects mutually reinforce each other and shape fertility preferences? (3) How do these relationships vary by gender? And (4) do the political attitudes of the actor and partner interact with each other in affecting fertility preferences? To answer these research questions, we analyzed dyadic data from a representative household survey (N = 1586 men and women from 793 heterosexually married couples). We employed random-intercept linear models on the fertility preferences of married couples with women of reproductive age (18–49).

The study contributes to the fertility literature in several ways. Empirically, this is the first study in Hong Kong that examines the political factors of fertility with representative quantitative data. Whether there is a politically shaped fertility pattern has important implications for the local population trend and composition and the effectiveness of the current fertility-related policies. Theoretically, this study contributes to understanding how political factors may shape fertility patterns in a context of political transition or crisis with a highly advanced economy. The results would extend our traditional cultural and economic explanations of fertility in the region. Methodologically, this is also the first study that analyzes dyadic data to examine the independent role of actor and partner effects of political attitudes on fertility.

Literature and Hypotheses

Political-Related Perceptions and Fertility Preferences

Dramatic change in the political environment can create uncertainty and confusion as individuals grapple with new political norms and standards. This can significantly impact fertility rates, as the heightened risks and uncertainties associated with the evolving political environment often discourage people from having children (Rodin, 2011). Previous research has indicated that substantial changes in leadership can produce similar effects on fertility, though the specific outcomes may vary among individuals with different political orientations (Aksoy & Billari, 2018; Dahl et al., 2022). While this study does not examine the political pattern of fertility behaviors as it requires longer time to observe the effects on fertility outcomes, it does explore potential differences in political preferences among individuals with varying political attitudes and levels of affective polarization. We hope to gain insights into how political orientations and polarization influence individuals' family choices and preferences within the political sphere.

Fertility preference is not a perfect predictor of behaviors, but past studies have shown that it is important to consider fertility preferences when understanding changing fertility levels and patterns (Casterline & Han, 2017; Cleland et al., 2020; Chen & Yip, 2017; Muller et al., 2022). There is a substantial body of literature devoted to studying the factors influencing fertility preferences (Bongaarts, 2001; Freeman et al., 2018; Kan & Hertog, 2017; Kan et al., 2019; Muller et al., 2022; Tong et al., 2023; Trinitapoli & Yeatman, 2018; Van de Kaa, 2001). Among the factors highlighted, Gauthier (2007) referred to a series of surveys in Europe and indicated that the biggest impediment to fertility concerns “children’s future”. However, the meaning of this term was left unexplained in the survey (Gauthier, 2013). Potentially, it could refer to social and economic problems that discourage young people from childbirth; others may be concerned about the sustainability of the environment and its implications for future generations (Arnocky et al., 2012). Our study analyzes people’s perception of “children’s future” in a political sense, which stems from political attitudes and political emotions.

First, people with different political attitudes toward political democracy and democratic values, such as their thoughts and positions about political contestations, the power of elected officials over government policies, personal autonomy, individual rights, and freedom of expression and belief, and the attitude towards inclusive political institutions (Templeman, 2022), see the transition from a semi-democracy to authoritarian regime differently. In the eyes of pro-democrats, Hong Kong is facing the deterioration of all those, and they are gloomy about Hong Kong’s political future, which trends toward authoritarianism with little indication of recourse (see Lui, 2023, for Hong Kong pro-democratic parents’ anxiety after the imposition of National Security Law). Thus, it is likely that people with stronger support for democracy will have lower fertility intentions and prefer fewer children.

Second, people’s feelings and emotional engagement with the political atmosphere will also affect their fertility preferences. Among all the political emotions that Hong Kong people have experienced during this period of change, we have identified that affective polarization, which refers to animosity between opposing camps, is the most accurate depiction of the present political atmosphere (cf. Lee, 2020, p. 22). Anti-ELAB movement has not only polarized opposing camps but has also unintentionally created a battleground for overt expressions of anger and hatred toward each another in the media, on the streets, and in day-to-day conversations with friends, relatives, as well as strangers (Bhowmik et al., 2023; Lai, 2023). Moral accusations have been drawn upon in those interactions; and the government’s imposition of the National Security Law to end contestations has created more grudges. While these feelings against opposing camps might not intuitively affect one’s fertility preference, they do reflect the intersubjective understanding of the social reality between groups (i.e., social hostility), which can create an unfavorable environment for raising children (cf. Genov, 1998). Here, we do not take affective polarization as a concept that shows feelings “locked in the inner sphere of an individual,” but rather, distinct from the ideological divide, it is relational, placing emotions in the public space (Schmitz, 2019). Affect is an embodied emotion—emotions that work through the bodies—shaped by the experience and interaction with “us” and “them” (Osler & Szanto, 2021). In other words, affective polarization reflects the extent of hostility in the political atmosphere in the interpersonal sense.

Political attitudes and emotions are often mutually reinforcing (Iyengar & Westwood, 2015; Klar et al., 2018; Osler & Szanto, 2021). We argue that pro-democratic attitudes and affective polarization are likely to further depress fertility. In other words, individuals do not only feel the presence of animosity but also engage with it as part of their group. In the case of Hong Kong, some pro-democrats might be swept up by political emotions—experiencing anger due to perceived political oppression (which is seen to be supported by the pro-government group) as well as a background concern for their pro-democratic camp in which they are engaged. Osler and Szanto (2021) argue that this is a political emotion in a thick sense. Past studies describe that the interaction of political identity and emotions could internalize feeling rules to guide people on how to act in public political events and express solidarity for political actions. Our study extends further by arguing that those feeling rules could guide non-political actions like choosing not to have children as a statement against the political atmosphere and institutions (Lui, 2023).

Past studies suggest that women and men’s political attitudes on social and political issues differ, with women having more pro-social values and strong partisanship (Lizotte, 2020). Mediated through political attitudes, scholars have found gender differences in affective polarization (Ondercin & Lizotte, 2021). In Hong Kong, studies so far have not provided proof of a gender divide in political attitudes (except on women’s rights) (Kennedy et al., 2008). However, we deduce that women might be more sensitive to the potential challenges and risks associated with having children in a politically uncertain environment due to their closer attention to child-rearing. On the other hand, men may be less influenced by political factors when it comes to fertility preferences, as their stronger identification with the provider’s role in the family may make them prioritize other factors, such as career advancement or financial stability, over political concerns when making decisions about family formation. However, further research is needed to fully understand the potential gender differences in the relationship between political attitudes and fertility preferences.

While individual characteristics and attitudes are important, it is also crucial to explore the influence of spousal characteristics on one's fertility preferences. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) in social psychology, developed by Kashy and Kenny (1999), suggested that the actions of individuals in each dyad are often not independent. Psychologists inform us that bonding and regulatory schemas enable individuals to perceive their intimate partners’ motivations (i.e., “dispositions to feel and behave in certain ways that meet a need or achieve a goal of the organism”), which affect fertility preferences (Miller et al., 2004, p. 194). Specific to our study, we argue that external shocks like political changes might create situations in which couples need to reinterpret each other’s motivations because they might have different take in terms of how political shock is important to fertility. They may follow the more weakly motivated partner’s wantedness because childbearing requires a long-term commitment from both partners (Miller et al., 2004). Hence, having a spouse with strong support toward democracy and affects may also reduce one’s fertility preference.

In addition, scholars argue that spouses often share similar values, beliefs, and attitudes due to political homophily (Huber & Malhotra, 2017; Iyengar et al., 2019), and like-minded couples often reinforce each other through persuasion and sharing political information and views in day-to-day life (Iyengar et al., 2019). Deduced from that, it is theoretically possible that when spouses are both pro-democratic, their pessimistic views about the future of society would converge and thus reinforce each other’s lesser desire for fertility. On the other hand, a competing hypothesis could be derived that if spouses hold differing political attitudes, their disagreements and conflicts may also discourage them from having children due to the potential conflicts and tensions that may arise within the family (cf. Soliz & Rittenour, 2012). Considering spousal characteristics and their influence on fertility preferences, our study can provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of political attitudes and their impact on family formation decisions.

Hypotheses of the Study

Based on the preceding discussion, we have derived two sets of hypotheses to investigate the relationship between political attitudes, affective polarization, and fertility preferences.

Main Effect Hypotheses

The first set of hypotheses, referred to as the main effect hypotheses, focuses on the individual and partner effects of political attitudes towards democracy and levels of affective polarization on one's fertility preferences.

Hypothesis 1a (Actor-Effect of Political Attitudes)

The respondents’ attitudes towards democracy are negatively associated with their fertility preferences.

Hypothesis 1b (Actor-Effect of Affective Polarization)

The respondents’ level of affective polarization is negatively associated with their fertility preferences.

Hypothesis 1c (Partner-Effect of Political Attitudes)

The spouses’ attitudes towards democracy are negatively associated with the respondents’ fertility preferences.

Hypothesis 1d (Partner-Effect of Affective Polarization)

The spouses’ level of affective polarization is negatively associated with the respondents’ fertility preferences.

Interaction Effect Hypotheses

In addition to the main effect hypotheses, we propose a second set of hypotheses known as the interaction effect hypotheses. These hypotheses investigate the potential interactions between various factors.

Hypothesis 2a (Polarization amplification effect) 1)

The respondents' affective polarization amplifies the actor’s negative effects of political attitudes on fertility preferences.

Hypothesis 2b (Gender Interaction)

The actor’s and partners’ effect of political attitudes and affective polarization on fertility preferences differ by gender, in which the effects are stronger for women.

Hypothesis 2c (Actor-Partner Interaction)

The actors’ effect of political attitudes and level of affective polarization on fertility preferences is moderated by the partner’s political attitudes and level of affective polarization.

These hypotheses provide a framework for investigating the complex relationships between political attitudes, affective polarization, and fertility preferences among married couples.

Methods

Data and Sample

This study analyzes quantitative dyadic data from a representative household survey conducted in Hong Kong in mid-2022 by the first author. The survey targeted married couples aged 18 or older who were residing in Hong Kong. Only married couples are targeted because it is very uncommon to have out-of-wedlock childbearing in Hong Kong (Yip et al., 2015). To ensure a representative sample, a two-stage sampling design was used. In the first stage, a random selection of residential addresses was made from the Frame of Quarters, an official list containing up-to-date residential addresses in Hong Kong. If multiple households were in a selected quarter, one household was randomly chosen. In the second stage, eligible married couples were randomly selected for interviews using the Kish-grid method. Both husbands and wives from the selected couples were invited for face-to-face interviews.

A bilingual questionnaire was used during the survey, and most questions were asked by the interviewers. However, for specific questions related to political orientations, respondents completed a self-administered questionnaire on a smart tablet. This was necessary because political issues can be highly sensitive in a polarized society like Hong Kong. To ensure confidentiality, all interviews were conducted separately on different occasions, and the spouses of respondents were not aware of the answers given by the respondents.

On average, each interview took approximately 23 min to complete, and respondents received HK$100 remuneration for their participation. Out of the 1558 addresses sampled, 1003 couples (1003 married men and 1003 married women) completed the interview, resulting in an overall response rate of 64.4%. Since we focus on fertility preferences in this study, we only focus on couples with a wife of reproductive age. World Health Organization defines reproductive age for women as starting at 15 years old and extending up to 49 years old. Hence, we excluded those couples with a wife at or older than 50 years. The dyadic data from both husbands and wives are then organized in a long format, comprising 1,586 individual units nested within 793 dyadic units. In each individual unit, respondents provided their own characteristics, while spousal characteristics were provided by their respective spouses.

Variables

Dependent variable. The dependent variable of this study is the respondents’ fertility preferences. In the survey, the respondents were asked how many children they preferred considering the social circumstances. The number ranged from 0 to 4.

Key independent variables. There are four key independent variables in this study: Respondents’ political attitudes and level of affective polarization, and spouses’ political attitudes and level of affective polarization. The political attitudes of respondents and their spouses were measured using an 8-item scale that was partially adopted from the Taiwan’s Election and Democratization Survey (TEDS) (Huang, 2003) and localized for the Hong Kong context. The scale measures the level of agreement with eight statements regarding democratic values, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Examples of the eight statements include “Leaders in the government should be strong and not make any compromise to the demands from the oppositions”, “The government cannot achieve great things if it is always tied up by the legislative council”, “People should always hold the same views. Otherwise, our society will become unstable”, “We should not ask for democracy in times of economic downturn” and “Social harmony is more important than human rights protection”. The scores for the eight items were then averaged to form the overall scale, which had high internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78). The scale ranges from 1 to 7, with a higher score indicating a more positive attitude towards democratic values. The spouses were also asked to answer the same questions, and their political attitudes were constructed in the same way. In the regression analysis, the variable is centered toward the mean in order to make the interpretation easier for the interaction effect models.

Affective polarization measures the emotional distance in rating among supporters of different political orientations. We adopted the feeling barometer (like-dislike scores) commonly used in the electoral studies literature to measure affective polarization (Druckman & Levendusky, 2019; Iyengar et al., 2019; Reiljan, 2020; Wagner, 2021). The respondents were asked to rate their feelings, from − 100 (entirely negative) to 100 (entirely positive), towards the supporters of five typical political orientations in Hong Kong—deep yellow, light yellow, neutral, light blue and deep blue. Five scores were collected from this question. We also asked the respondents to identify their political orientations. We adopted Wagner (2021)’s distance score approach by calculating the average absolute distance between the score toward supporters of the respondents’ own political orientations and the scores toward supporters of other groups. The raw score range of the affective polarization is from 0 to 200. A higher score represents a larger distance in the feeling between in-group and out-group supporters, which indicates a higher level of affective polarization—the respondents feel political out-groups as very distanced. For example, a score of 200 means the respondents rated their in-group supporters as 100 (entirely positive) while rated supporters of the other four groups as − 100 (entirely negative). In other words, the respondents rate people with the same political orientation very positively and rate people from other orientations very negatively. Meanwhile, a lower score indicates a lower level of affective polarization—the respondents feel similarly across supporters of political in-groups and out-groups. A zero score indicates the respondents gave the same rating to the supporters of their own political orientations and the supporters of other orientations. This variable is also centered toward the mean in the regression models.

Control variables. To minimize the confounding bias, we controlled for several sociodemographic variables that are correlated with both political attitudes and fertility preferences. These variables include the respondents’ and their spouses’ age (in years), college education attainment (1 = yes; 0 = no), nativity status (1 = locally born; 0 = otherwise), their work status (1 = employed; 0 = not employed) and the monthly household income (in logged HK$). We also attempted to control other variables, such as gender attitudes, and the number of children, in additional analyses. The results of the additional analyses remain similar to the findings presented below. For these two variables, some may argue that their relationships with fertility preferences are complex and unclear whether they are confounding or mediating variables. To keep the models parsimonious, we do not include these variables in the main analysis.

Analytic Strategies and Procedures

We adopt the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM), a well-established analytical model for examining interpersonal relationships (Campbell & Kashy, 2002; Kashy & Kenny, 1999), as our analytical framework. APIM can be analyzed with structural equation models or multilevel models. In this study, we adopted the latter approach (Campbell & Kashy, 2002) by estimating two-level random-intercept linear regression models to handle the intra-class correlation with the dyadic data structure. We employed four nested models. Model 1 is the main effect model that assesses Hypotheses 1a–1d, which is about the actor and partner effects of political attitudes and affective polarization on the respondents’ fertility preferences while controlling for the control variables. Model 2 to Model 4 are interaction effect models, each testing one set of interaction effect hypotheses (Hypotheses 2a–2c). Model 2 examines the interaction between the actor effects of political attitude and affective polarization on fertility preferences (Hypothesis 2a). Model 3 examines whether the actor and partner effects of political variables differ by the respondents’ gender (Hypothesis 2b). Model 4 examines whether the actor and partner effects of political attitudes interact with each other (Hypothesis 2c). For the interaction effects detected in Model 2 to Model 4, the average marginal effects and the predicted values across different combinations of constituent variables are plotted in figures to help interpret the results.

We conducted several sets of additional analyses on top of the main results presented in Table 2. First, as mentioned above, we additionally controlled for gender attitudes and the number of children because politically conservative respondents may also be conservative in family and gender values, which may affect their fertility preferences. We confirm that our main findings of this study are robust to the inclusion of these variables. The direction and statistical significance of the relationships are similar with and without these additional control variables. Second, we also tested the non-linearity of the effects of the key variables by including the squared terms or in a logged form. The results also remain the same. Lastly, we also extended our analysis to the whole sample without applying the age restriction sample selection criteria. The relationships shown in our findings remain the same but only with higher significance levels due to the larger analytic sample size. The results of additional analyses are available in the appendices (available as online supplementary materials).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study. On average, the respondents prefer to have 1.245 (SD = 0.828) children, considering the social circumstances. Regarding the political variables, the respondents, on average, score 4.249 (SD = 0.821) on the political attitudes scale, which measures their support for democracy. The score of 4.249 is slightly above the mid-point of the scale, which ranges from 1 to 7, implying that the respondents, on average, are more prone to support democratic values. The raw score of affective polarization is 71.598 (SD = 34.427), which measures the average distance in the emotional rating between supporters of their political orientation and the supporters of political out-groups, with a maximum raw score of 200. The raw score is not intuitive to interpret. Hence, we provide a case scenario for interpreting the score. Person A, with a deep-yellow orientation, rated the in-group supporters with a score of 80 out of a range from − 100 to 100, while rated the light-yellow, neutral, light-blue and deep-blue supporters with scores of 60, 20, − 10, and − 40. The raw score of affective polarization is 72.5 (around the average level in this sample). An average score of around 72 indicates quite a high level of affective polarization already, indicating that they think of the supporters of opposing groups negatively.

Now, we turn to the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. The average age of the respondents is 37.084 years (SD = 6.442). Around 37% of the respondents obtained a college degree, with 81% with a paid job. Most of the respondents (84.2%) were locally-born residents. Since the sample is a dyadic sample of heterosexual married couples, the sample contains the same proportion of men and women, and the spouses’ characteristics mirror the respondents’ characteristics. The average monthly household income is HK$37,000. These sample characteristics are similar to the micro-data of a subset extracted from the Population Census using the same sampling criteria.

Figure 2 displays the sub-group averages of fertility preferences by the quintiles of respondents’ and spouses’ political attitudes and affective polarization. The upper panel of Fig. 2 shows the bivariate relationship between respondents’ and spouses’ political attitudes and respondents’ fertility preferences. Respondents clearly prefer having more children when they have lower support for democracy, while the relationship between spouses’ political attitudes and respondents’ fertility preferences is weaker and close to zero. The bottom panel of Fig. 2 shows the bivariate relationship between the respondents’ and spouses’ levels of affective polarization and respondents’ fertility preferences. Results of statistical tests show that the differences in respondents’ fertility preferences among respondents with different levels of affective polarization are very weak.

Regression Analysis

Table 2 reports the results of random-intercept models on fertility preferences. Model 1 is the main-effect model that includes the political attitudes and affective polarization of the respondents and their spouses while controlling for their socio-demographic background. The results of Model 1 show that the respondents’ political attitudes are negatively associated with their fertility preferences (b = − 0.082, SEb = 0.026), while respondents’ affective polarization has no relationship with their fertility preferences. In addition, spouses’ political attitudes and affective polarization are not associated with the respondents’ fertility preferences. In other words, H1a is confirmed but we do not have evidence to support for H1b to H1d.

Model 2 to Model 4 are interaction effect models, each including different interaction terms. Model 2 tests the polarization amplification hypothesis—whether the respondents’ affective polarization strengthens the negative association between the respondents' political attitudes and their fertility preferences. The results show that the interaction between respondents’ political attitudes and affective polarization is negative. The negative association between the respondents’ political attitudes and their fertility preferences is stronger if these respondents hold a higher level of affective polarization. The polarization amplification hypothesis is supported by our data. Model 3 tests whether the associations between respondents’ political attitudes, affective polarization, and fertility preferences are moderated by gender. However, the interaction effects are minimal. In other words, there is no statistical evidence to suggest that the association between respondents’ political attitudes and their fertility preferences is different for men and women. Model 4 tests the actor-partner interaction hypothesis—whether the respondents’ and spouses’ political variables interact with each other to affect the respondents’ fertility preferences. The interaction terms are close to zero, suggesting that the negative association between respondents’ political attitudes and their fertility preferences holds regardless of their spouses’ attitudes. To conclude the findings from the four models, the respondents’ political attitudes are negatively associated with their fertility preferences, regardless of their gender and their spouses’ attitudes. This negative association is stronger when they have a higher level of affective polarization.

Among the control variables, it is also noteworthy that respondents’ college education (b = − 0.85, SEb = 0.043) is negatively associated with the respondents’ fertility preferences. Comparing the sizes of coefficients between college education and political attitudes, the results show that the strength of association between political attitudes and fertility preferences is quite substantial, with one unit increase in political attitudes (on a scale ranging from 1 to 7) almost identical to a college degree (b = − 0.082 vs. − 0.085). Respondents’ and spouses’ work status and nativity status are also negative factors of the respondents’ fertility preferences. Respondents who have a job (b = − 0.122, SEb = 0.060) and whose spouse has a job (b = − 0.124, SEb = 0.060), on average, prefer fewer children than non-working respondents and those with a jobless spouse. Locally-born respondents (b = − 0.212, SEb = 0.054) and respondents with a locally-born spouse (b = − 0.155, SEb = 0.054) also preferred fewer children than migrant respondents and those with a migrant spouse. These findings are consistent with the existing literature.

Interpreting the Interaction Effect of Political Attitudes and Affective Polarization

Figure 3 visualizes the interaction effect between respondents’ political attitudes and the level of their affective polarization on fertility preferences (polarization amplification hypothesis) in a more intuitive way. When the respondents have a lower level of affective polarization (i.e., below mean), the average marginal effects of political attitudes are close to zero. In other words, having a higher level of support for democracy does not necessarily lead to lower fertility preferences when the respondents do not have a strong negative emotion towards political out-groups.

On the other hand, for respondents with an average level of affective polarization, the average marginal effect is negative (b = − 0.064, SEb = 0.027). The average marginal effects are more negative for respondents with a higher level of affective polarization (higher than the mean level). For example, the average marginal effects of political attitude for respondents with higher levels of affective polarization (0.5, 1 and 1.5 standard deviations above the mean level) are − 0.090, − 0.117 and − 0.144, respectively. The size of the average marginal effects of political attitudes for the respondents with high levels of affective polarization is comparable to other consistent factors of fertility, such as work and nativity status.

In Fig. 4, the predicted fertility preferences based on respondents' political attitudes and affective polarization are plotted. For those with a lower level of affective polarization (M-1SD), the expected preferred number of children is approximately 1.25, regardless of political attitudes. On the other hand, for those with average polarization levels, the preferred number of children ranges from around 1.46 (lowest democracy support) to 1.08 (highest democracy support). For respondents with a higher level of affective polarization, the preferred number of children ranges from 1.66 (lowest democracy support) to 0.96 (highest democracy support). This indicates that respondents with high affective polarization are more responsive to their political attitudes when it comes to fertility preferences. Furthermore, those with high affective polarization and strong support for democracy prefer fewer children than other respondents.

Predicted preferred number of children with 95% CI by respondents’ political attitudes and level of affective polarization. Notes: Low, average, and high polarization levels refer to the mean level minus 1 standard deviation, the mean level, and the mean level plus 1 standard deviation, respectively

Discussion

The mainstream fertility literature has extensively discussed the cultural and structural factors contributing to the ultra-low fertility rate in East Asia, which currently holds the lowest fertility rate worldwide (Jones, 2019; Raymo et al., 2015). These factors include the rise of individualism, gender inequalities, education fever, work-family conflict and housing affordability (Anderson & Kohler, 2013; Cheng, 2020; Jones, 2019). This study goes beyond the traditional cultural and structural explanations of low fertility in the region and seeks to broaden the understanding of the phenomenon by examining the potential link between politics and fertility. While Gietel-Basten and Chen (2023) found a sharp decline in the fertility rate since the onset of the massive-scale Anti-ELAB movement in 2019, their use of aggregate-level time-series data has its limitations in further investigating the factors of such a decline. Our dyadic survey data from Hong Kong provides valuable insight for filling this research gap.

In the context of this study, our data reveal a distinct political pattern in fertility preferences, specifically highlighting the negative correlation between attitudes toward democracy and individuals’ fertility preferences. This suggests that political factors play an important role in shaping fertility patterns in this particular context. Individuals with stronger support for democracy may exhibit lower preferences for having children. While the hostile feelings toward political out-groups from the respondents and their spouses are not directly related to one’s fertility preferences, the hostile feelings of political out-groups at the respondent level amplified the deterring impact of democratic values on fertility preferences. This polarization amplification hypothesis proposed in this study is the first study in the literature to highlight the important role of affective polarization in the population process (Iyengar et al., 2019).

Other than the polarization amplification hypothesis, we have found no evidence to support the other two hypotheses regarding gender and actor-partner interaction effects. While previous studies have indicated that mothers often prioritize the environment in which their children will grow up, it appears that the fertility preferences of men and women in Hong Kong are equally responsive to the political environment. Furthermore, the findings suggest that the respondents’ and spouses’ attitudes do not interact to shape the respondents’ fertility preferences. However, since the fertility preferences of both husbands and wives can impact the actual fertility outcome (Tong et al., 2023), spousal political attitudes may still influence the fertility outcome at the couple level by influencing the fertility preferences of the spouse (but not the respondents themselves).

By exploring the intricate relationship between political factors and fertility patterns, this study sheds light on how political dynamics may influence fertility preferences in a highly developed economy experiencing a dramatic political transition from a semi-democratic regime to an authoritarian one (Davis, 2022). The association found in our data is believed to be largely connected to the widespread discontent in Hong Kong regarding political developments among supporters of democratic parties. Similar effects were observed in relation to emigration (Li & Liao, 2023; Lui et al., 2022). It is important to note that the direction and strength of the association between political attitudes and fertility preferences, as revealed in this study, may be context-dependent. Specifically, the level of affective polarization in Hong Kong has been very high since the Anti-ELAB movement in 2019 (Lai, 2023). Different political regimes with different levels of affective polarization can lead to different directions and strengths of associations. However, further research is needed to confirm this.

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between political attitudes, affective polarization and fertility preferences, there are several limitations that need to be addressed in future research. Firstly, this study focuses on fertility preferences and not fertility behaviors, which may differ from each other (Casterline & Han, 2017; Cleland et al., 2020; Chen & Yip, 2017; Muller et al., 2022). Even though couples not holding favorable attitudes to democracy may have higher fertility preferences, their preferences may not be actualized due to other reasons. On the other hand, couples preferring fewer children may still have more than the preferred number of children due to pressures from their family and relatives. Nevertheless, it is almost impossible for our survey data collected in 2022 to look for this relationship because the dramatic political transition only took place in 2019, and it would take more time for the couples to actualize their fertility ideal into outcomes. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the association between political attitudes and fertility outcomes, future research could collect fertility history data from larger representative samples to explore this topic.

Second, it is unknown whether the association between political attitudes and fertility preferences in Hong Kong will be weakened in the future. The association between political attitudes and fertility preferences can be observed in our data collected in 2022, which is three years after the massive social protests and two years after the implementation of the National Security Law. If the tightened political control disappointed the supporters of the democratic camp, leading to these supporters not being willing to raise children in this new political environment, then it is meaningful to know whether these supporters will eventually accept the new political reality and increase their fertility preferences back to the pre-2019 level. In other words, future research is needed to understand to what extent the impact of political transition would be long-lasting.

Additionally, this study represents the initial step toward understanding the relationship between political attitudes and fertility. However, it is challenging to establish causal relationships between fertility preferences and political attitudes based on our cross-sectional data. While the results reported in this study could be the result of causal relationships between political orientations and fertility preferences, they could also be partly influenced by selective emigration. Notably, the recent political changes have led to a significant number of supporters of the democratic movement emigrating (Kan et al., 2023; Li & Lao, 2023; Lui et al., 2022). Lui et al. (2022) observed that parents who participated in the 2019 protests had a stronger intention to migrate compared to those participants without children. If pro-democrats with a greater desire for more children tend to leave Hong Kong while pro-democrats with lower fertility preferences tend to stay, then this selective emigration pattern could introduce a selection bias to the relationship between political attitudes and fertility preferences. Further empirical studies that examine the relationships between political attitudes and fertility preferences among Hong Kong emigres in popular destination societies, including those in the UK and Canada, could further examine this potential selectivity issue. If further investigations suggest that the cross-sectional association between political attitudes and fertility preferences largely reflects the outcomes of selective migration, the implications could be significant for other societies experiencing a surge in politically driven emigration. Demographers may investigate whether selective migration in these societies leads to discernible political patterns in terms of fertility intentions and behaviors within the home societies.

Besides, even if there is a causal relationship between political attitudes and fertility, further research is still necessary to explore the specific mechanisms that underlie this relationship. By investigating potential mechanisms, researchers can develop theories that may be applicable in different contexts and gain a more nuanced understanding of the complex relationship between these variables. For instance, if pro-democrats are less likely to have children, it may be attributed to their desire to avoid childbearing in an uncertain political environment, where they worry about the upbringing of their children (Gietel-Basten & Chen, 2023). It could also be a symbolic act of political resistance to express their discontent (Lui, 2023). Future qualitative research is highly valuable in exploring and clarifying the nature of this political pattern of fertility.

While there are several avenues for future research to expand upon the findings and address the limitations mentioned, the political patterns of fertility preferences in Hong Kong have several important theoretical, policy and political implications. First, of many cultural and structural factors that are identified in the literature, no existing studies have pointed toward the political factors of ultra-low fertility in Hong Kong. While we refrain from generalizing the findings to other contexts, dramatic political transitions are not rare. For example, the presidential election of Donald Trump in the United States and the referendum on Brexit in the UK both brought major political impacts and heightened the level of affective polarization in these societies (Hobolt et al., 2021; Iyengar et al., 2019). The findings of this study call for more research on these societies to better understand how intense political divides may impact the population structure in the long run. Second, policymakers should pay attention to the patterns of politically linked fertility preferences because it may affect the effectiveness of the population policies. The mainstream population policy package includes parental leave, financial incentives and other family-friendly policies aimed at assisting young couples in managing their financial burdens and resolving work-family conflicts (Cheng, 2020; Cheung & Kim, 2022; Jones, 2019; Lui & Cheung, 2021). While these policies may help couples to actualize their fertility ideals (Lui & Cheung, 2021), it will not work effectively if the couples have fewer children because they actually prefer fewer children (Cheung, 2023).

Finally, it is important to consider the potential political consequences of fertility preferences that are strongly linked to political attitudes (Teitelbaum, 2015). Whether or not the association found in this study reflects a causal relationship, this pattern could have implications for the future political landscape. Previous studies have shown that the political attitudes of parents are associated with the political attitudes of their children (Hatemi & McDermott, 2016). Differential fertility may gradually weaken the support for liberal values (Vogl & Freese, 2020). If supporters of democratic reforms continue to have lower fertility preferences and consequently have fewer children, the number of supporters for democratic reforms will decline. This, in turn, could impact the prospects of the democratic movement in the future. The prospect of the democratic movement becomes even dimmer when considering that, alongside this political pattern of fertility, there is a politically driven surge of emigration, in which supporters of the democratic movement are fleeing from the city (Lui et al., 2022).

References

Aksoy, O., & Billari, F. C. (2018). Political Islam, marriage, and fertility: Evidence from a natural experiment. American Journal of Sociology, 123(5), 1296–1340.

Anderson, T., & Kohler, H. P. (2013). Education fever and the East Asian fertility puzzle: A case study of low fertility in South Korea. Asian Population Studies, 9(2), 196–215.

Arnocky, S., Dupuis, D., & Stroink, M. L. (2012). Environmental concern and fertility intentions among Canadian university students. Population and Environment, 34, 279–292.

Bhowmik, M. K., Kennedy, K. J., Chan, A. H. T., & Gube, J. C. C. (2023). “Heroes and Villains”: Media constructions of minoritized groups in Hong Kong’s season of discontent. Journal of Asian and African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096231192326

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. Population and Development Review, 27, 260–281.

Campbell, L., & Kashy, D. A. (2002). Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user–friendly guide. Personal Relationships, 9(3), 327–342.

Casterline, J. B., & Han, S. (2017). Unrealized fertility: Fertility desires at the end of the reproductive career. Demographic Research, 36, 427–454.

Chen, M., & Yip, P. S. (2017). The discrepancy between ideal and actual parity in Hong Kong: Fertility desire, intention, and behavior. Population Research and Policy Review, 36, 583–605.

Cheng, Y. H. A. (2020). Ultra-low fertility in East Asia. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 18, 83–120.

Cheng, Y. H. A., & Hsu, C. H. (2020). No more babies without help for whom? Education, division of labor, and fertility intentions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(4), 1270–1285.

Cheung, A. K. L. (2023). Couples’ housework participation, housework satisfaction and fertility intentions among married couples in Hong Kong. Asian Population Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2023.2252633

Cheung, A. K. L., & Kim, E. H. W. (2022). Domestic outsourcing in an ultra-low fertility context: Employing live-in domestic help and fertility in Hong Kong. Population Research and Policy Review, 41(4), 1597–1618.

Cleland, J., Machiyama, K., & Casterline, J. B. (2020). Fertility preferences and subsequent childbearing in Africa and Asia: A synthesis of evidence from longitudinal studies in 28 populations. Population Studies, 74(1), 1–21.

Dahl, G. B., Lu, R., & Mullins, W. (2022). Partisan fertility and presidential elections. American Economic Review: Insights, 4(4), 473–490.

Davis, M. C. (2022). Hong Kong: How Beijing perfected repression. Journal of Democracy, 33(1), 100–115.

Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 114–122.

Freeman, E., Ma, X., Yan, P., Yang, W., & Gietel-Basten, S. (2018). ‘I couldn’t hold the whole thing’: The role of gender, individualisation and risk in shaping fertility preferences in Taiwan. Asian Population Studies, 14(1), 61–76.

Gauthier, A. H. (2007). The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: A review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(3), 323–346.

Gauthier, A. H. (2013). Family policy and fertility: Do policies make a difference? In A. Buchanan & A. Rotkirch (Eds.), Fertility rates and population decline: No time for children? (pp. 269–287). Palgrave Macmillan.

Genov, N. (1998). Transformation and anomie: Problems of quality of life in Bulgaria. Social Indicators Research, 43, 197–209.

Gietel-Basten, S., & Chen, S. (2023). From protests into pandemic: Demographic change in Hong Kong, 2019–2021. Asian Population Studies, 19(2), 184–203.

Hatemi, P. K., & McDermott, R. (2016). Give me attitudes. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 331–350.

Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J., & Tilley, J. (2021). Divided by the vote: Affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1476–1493.

Huang, C. (2003). Taiwan’s election and democratization study, 2001 (TEDS2001) (D00075) [data file]. Survey Research Data Archive, Academia Sinica. https://doi.org/10.6141/TW-SRDA-D00075-1

Huber, G. A., & Malhotra, N. (2017). Political homophily in social relationships: Evidence from online dating behavior. The Journal of Politics, 79(1), 269–283.

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 129–146.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Jones, G. W. (2007). Delayed marriage and very low fertility in Pacific Asia. Population and Development Review, 33(3), 453–478.

Jones, G. W. (2019). Ultra-low fertility in East Asia: Policy responses and challenges. Asian Population Studies, 15(2), 131–149.

Kan, M. Y., & Hertog, E. (2017). Domestic division of labour and fertility preference in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Demographic Research, 36, 557–588.

Kan, M. Y., Hertog, E., & Kolpashnikova, K. (2019). Housework share and fertility preference in four East Asian countries in 2006 and 2012. Demographic Research, 41, 1021–1046.

Kan, M. Y., Loa, S. P., & Richards, L. (2023). Generational differences in local identities, participation in social movements, and migration intention among Hong Kong people. American Behavioral Scientist. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642231192023

Kashy, D. A., & Kenny, D. A. (1999). The analysis of data from dyads and groups. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Kennedy, K. J., Hahn, C. L., & Lee, W. O. (2008). Constructing citizenship: Comparing the views of students in Australia, Hong Kong, and the United States. Comparative Education Review, 52(1), 53–91.

Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., & Ryan, J. B. (2018). Affective polarization or Partisan Disdain? Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(2), 379–390.

Lai, R. Y. (2023). Home as a site of resistance/repression? The intersection of family, politics and the Hong Kong 2019 protest movement. The Sociological Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261231175226

Lee, F. (2020). Solidarity in the anti-extradition bill movement in Hong Kong. Critical Asian Studies, 52(1), 18–32.

Lee, F., Yuen, S., Tang, G., & Cheng, E. W. (2019). Hong Kong’s summer of uprising. China Review, 19(4), 1–32.

Li, Y. T., & Liao, B. J. (2023). An “Unsettling” Journey? Hong Kong’s exodus to Taiwan and Australia after the 2019 protests. American Behavioral Scientist. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642231192025

Lizotte, M. K. (2020). Gender differences in public opinion values and political consequences. Temple University Press.

Lui, L. (2023). National Security education and the infrapolitical resistance of parent-stayers in Hong Kong. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 58(1), 86–100.

Lui, L., & Cheung, A. K. L. (2021). Family policies, social norms and marital fertility decisions: A quasi‐experimental study. International Journal of Social Welfare, 30(4), 396–409.

Lui, L., Sun, K. C. Y., & Hsiao, Y. (2022). How families affect aspirational migration amidst political insecurity: The case of Hong Kong. Population, Space and Place, 28(4), e2528.

Miller, W., Severy, L., & Pasta, D. (2004). A framework for modelling fertility motivation in couples. Population Studies, 58(2), 193–205.

Müller, M. W., Hamory, J., Johnson-Hanks, J., & Miguel, E. (2022). The illusion of stable fertility preferences. Population Studies, 76(2), 169–189.

Ondercin, H. L., & Lizotte, M. K. (2021). You’ve lost that loving feeling: How gender shapes affective polarization. American Politics Research, 49(3), 282–292.

Osler, L., & Szanto, T. (2021). Political emotions and political atmospheres. In D. Trigg (Ed.), Atmospheres and shared emotions (pp. 162–188). Routledge.

Raymo, J. M., Park, H., Xie, Y., & Yeung, W. J. J. (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 471–492.

Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and loathing across party lines’(also) in Europe: Affective polarisation in European party systems. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 376–396.

Rodin, J. (2011). Fertility intentions and risk management: Exploring the fertility decline in Eastern Europe during transition. Ambio, 40, 221–230.

Schmitz, H. (2019). New phenomenology: A brief introduction. Mimesis.

Soliz, J., & Rittenour, C. E. (2012). Family as an intergroup arena. In H. Giles (Ed.), The handbook of intergroup communication (pp. 331–343). Routledge.

Teitelbaum, M. S. (2015). Political demography: Powerful trends under-attended by demographic science. Population Studies, 69(sup1), S87–S95.

Templeman, K. (2022). How democratic is Taiwan? Evaluating twenty years of political change. Taiwan Journal of Democracy, 18(2), 1–24.

Tong, Y., Gan, Y., & Zhang, C. (2023). Whose preference matters more? Couple’s fertility preferences and realization in the context of China’s two-child policy. Journal of Family Issues, 45(2), 471–501.

Trinitapoli, J., & Yeatman, S. (2018). The flexibility of fertility preferences in a context of uncertainty. Population and Development Review, 44(1), 87.

Van de Kaa, D. J. (2001). Postmodern fertility preferences: From changing value orientation to new behavior. Population and Development Review, 27, 290–331.

Vogl, T. S., & Freese, J. (2020). Differential fertility makes society more conservative on family values. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(14), 7696–7701.

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 69, 102199.

Wu, Y., & Shen, F. (2020). Negativity makes us polarized: A longitudinal study of media tone and opinion polarization in Hong Kong. Asian Journal of Communication, 30(3–4), 199–220.

Yip, P. S. F., Chen, M., & Chan, C. H. (2015). A tale of two cities: A decomposition of recent fertility changes in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Asian Population Studies, 11(3), 278–295.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Hong Kong Baptist University Library. This study was funded by the Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, Hong Kong (Grant No. GRF/12600021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the first author’s university.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, A.KL., Lui, L. The Personal is Political: Political Attitudes, Affective Polarization and Fertility Preferences in Hong Kong. Popul Res Policy Rev 43, 22 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09868-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09868-5