Abstract

Attitudes towards sexual minorities have undergone a transformation in Western countries recently. This has led to an increase in research into the experiences of sexual minorities in a variety of life domains. Although parenthood is a valued life goal only a few small-scale studies have looked into the parenthood goals of individuals in relation to their sexual orientation. The aims of this study are to analyse the diversity of sexual orientation, the factors associated with it and the relationship to fertility intentions among adolescents aged 16 to 19. The study draws on a nationally representative youth survey conducted in 2020 in Estonia (N = 1624), and employs descriptive methods and logistic and linear regression models. The results show that adolescents in Estonia exhibit considerable diversity of sexual orientation, with one-fifth reporting some degree of attraction to their own sex. The minority sexual orientation is more frequent among groups which can be regarded as more open or exposed to new behaviours, but is also associated with a disadvantaged family background. The results reveal a clear negative association between the intended number of children and the minority sexual orientation, which is not explained by other available variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attitudes towards sexual minorities have changed profoundly in Western countries over recent decades (Brewer & Wilcox, 2005; Flores, 2019). During a relatively short period, we have witnessed a shift from homosexual behaviour being considered a criminal offence, to legal recognition of same-sex partnerships and marriages, and the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sexual minority orientation. In the European Union, member states are advised to regularly monitor the situation of sexual minorities in various domains of life (The European Parliament, 2014). In this context, it is increasingly recognised that reliable information has a pivotal role to play in documenting the dynamics and characteristics of sexual minority populations; and in informing the development and implementation of policies, programmes and services that are aimed to address challenges they face (Gates, 2012; Valfort, 2017). Although the availability of statistics on sexual minority populations is still limited, several national statistical offices have started to publish estimates for these groups (for a recent overview, Wilson et al., 2021).

Regarding family demography, the recognition of same-sex registered partnerships and same-sex marriages has added a whole new strand of research into same-sex couple relationships. The family-demographic literature deals with a variety of topics ranging from the formation and stability of same-sex unions (Andresson & Noack, 2010; Andersson et al., 2006; Bennett, 2017; Joyner et al., 2017; Kolk & Andresson, 2020; Manning et al., 2016; Prince et al., 2020; Wiik et al., 2014;) to outcomes of children who grow up in same-sex parent households (Biblarz & Stacey, 2010; Calzo et al., 2017; Rezcek et al., 2016). However, only a few studies have explored parenthood intentions among sexual minority groups. This is surprising given the fact that information on fertility preferences is collected as a part of many surveys, and a large literature on intended fertility exists. US studies, based on representative samples, have shown that gay men and lesbian women are less likely than their heterosexual counterparts to express the desire and intention to become parents (Riskind & Patterson, 2010; Tate et al., 2019), whereas parenting intentions of bisexual men and women more resemble those of heterosexual individuals (Riskind & Tornello, 2017). The existing European studies of fertility intentions among sexual minority groups have drawn their evidence from surveys using convenience samples (Baiocco & Laghi, 2013; Gato et al., 2020; Kranz et al., 2018).

This study investigates the association between fertility intentions and sexual orientation among late adolescents in Estonia, based on a youth survey conducted in 2020. The motivation behind this study stems from the fact that intentions are an important link in the chain leading to the decision to have a child, and are considered to be a major determinant of reproductive behaviour, at least for different-sex couples (Philipov & Bernardi, 2011; Schoen et al., 1999). Furthermore, it can be assumed that the parenthood intentions of sexual minority groups may differ from that of the majority population, reflecting biological constraints of homosexual relationships related to childbearing as well as social climates, which may make it more difficult for people belonging to sexual minorities to become parents. In this study, we seek evidence regarding the extent to which the intentions of young people, concerning the size of their future families, differ according to sexual orientation.

We are also interested in the background factors associated with majority and minority sexual orientations. Our interest is driven by evidence found in a number of studies of an increase in the share of people who have had same-sex partners (Butler, 2000, 2005; Turner et al., 2005; Twenge et al., 2016). Research on partnerships and fertility has shown that new patterns of behaviour, such as cohabitation and non-marital childbearing, tend to exhibit distinct social gradients, which are considered essential for understanding the partnership dynamics and fertility in contemporary societies (Matysiak et al., 2014; Lesthaeghe, 2020; Perelli-Harris & Lyons-Amos, 2016; Perelli-Harris et al., 2010). In a similar spirit, we investigate background factors associated with minority sexual orientation among our study population.

Our study contributes to the literature in multiple ways. First, our study focusses on young men and women aged 16 to 19 years who are often excluded from family and fertility surveys or represented in small numbers, which prevents reliable results from being obtained for them. However, in the context of the present study, the results pertaining to late adolescents are of considerable interest, as the proportion of those with a minority sexual identity seems to be increasing in younger generations (Carvalho et al., 2017; Mishel et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2020). Furthermore, their parenthood intentions are important in view of future fertility levels. Second, while earlier studies of parenthood intentions among sexual minority populations have often focussed on specific minority groups (e.g. lesbians or gays), our study covers a wider spectrum of groups. In particular, we provide evidence on individuals with moderate same-sex attraction, who form a relatively large group, but have rarely been separately explored in the previous research. Third, our study draws on a nationally representative survey, so it is unlikely that our results are subject to selection bias, which may be a problem in analyses of sexual minority groups based on convenience samples. Finally, research on parenthood intentions among sexual minority groups has been limited to a small number of countries. By adding a new context, our study contributes to a more comprehensive account of sexual minority populations in contemporary societies.

Theoretical Perspectives and Previous Findings

Sexual orientation is conceived to be a characteristic of individuals, which has three distinct elements: sexual attraction, referring to sexual feelings; sexual behaviour, referring to sexual activity; and sexual identity, referring to how someone classifies their sexuality (Geary et al., 2018; Moleiro & Pinto, 2015). Surveys have shown that these elements do not overlap empirically (Diamond, 2003). Not all individuals who experience same-sex attraction are engaged in same-sex sexual behaviour or report a sexual minority identity in surveys. However, psychologists argue that sexual attractions are the most valid way of quantifying sexual orientation, because attractions motivate behaviour and identity rather than the other way around (Floyd & Bakeman, 2006; Saewyc et al., 2004). Asking about sexual attraction is considered to be an appropriate basis for classifying young people, some of whom have not yet become sexually active, into groups based on sexual orientation (Költő et al., 2018).

Much of the existing knowledge on how sexual orientation is formed stems from developmental psychology. Like many other traits in individuals, sexual orientation is considered to be multifactorial, shaped by biological and psychosocial factors (Bailey et al., 2016). Twin studies suggest that genetic factors may account for approximately one-third of the variation in sexual orientation, while two-thirds are explained by non-genetic factors (Alanko et al., 2010). Life-history theory seeks to explain the role of these factors in a diversity of organisms, especially in their reproductive behaviour (Del Guiduce et al., 2015). In humans, this framework focusses on the influence of early-life conditions (e.g. resource scarcity, low parental investment, maternal anxiety/depression) on sexual behavioural traits across the life span (Ellis, 2004; Quinlan, 2003).

The life-history approach is also relevant for the study of sexual orientation, as the early-life conditions suggested by life-history theory may constitute a source of non-genetic factors in its formation (Xu et al., 2018). Empirical studies have identified several early-life factors, such as low birth weight, short duration of breastfeeding, high number of older brothers, low prenatal family socio-economic position, physical or sexual abuse, witnessing violence in childhood and poor relationship with parents, which may be associated with the development of minority sexual orientation (Blanchard, 2018; Blanchard & Ellis, 2001; Corliss et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2010; Saewyc et al., 2006; Wells et al., 2011).

Due to the frequent use of cross-sectional research designs, surveys of adults, which are susceptible to recall biases and other limitations, these associations may not necessarily be causal (Bailey et al., 2016). For instance, several alternative mechanisms may drive the association between childhood maltreatment and minority orientation. According to one explanation, children and adolescents who disclose their same-sex orientation may be targeted for maltreatment (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; Saewyc et al., 2006). Another explanation, similar to the previous one, suggests that sexual minorities are predisposed to non-conforming behaviours in childhood, and may therefore experience maltreatment (Alanko et al., 2010; Rieger et al., 2008). Furthermore, it has been asserted that this correlation may also reflect differential recall, for instance, due to greater willingness to admit stigmatising childhood experiences among sexual minority groups (Corliss et al., 2002). Finally, it has been asserted that maltreatment may contribute to a loss of self-worth, and as a result, maltreated persons may be more willing to adopt another stigmatised identity, i.e. minority sexual orientation (Saewyc et al., 2006). The causal mechanisms driving the associations between early-life experiences and sexual orientation can be best studied prospectively through repeated measures; it has also been suggested that an instrumental variable approach can provide consistent estimates of the effect of an exposure on outcome, even when reverse causation or unmeasured common factors affecting the outcome and exposure are present. Studies employing these more rigorous approaches have shown that there may indeed be causal mechanisms driving the association between early-life factors and sexual orientation (Roberts et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2019, 2021).

Research on the relationship between early-life factors and sexual orientation has focussed on influences operating at the individual and family level. Other studies, drawing on large-scale social surveys, have shown differences in sexual orientation associated with socio-demographic and contextual factors. For instance, Rogers and Turner (1991) found a positive relationship for father’s educational attainment and same-sex sexual contact among men. Other studies have found corroborating evidence. Billy et al. (1993) reported the occurrence of same-sex sexual activity to be positively correlated to men’s education. Laumann et al. (1994) found that education was positively associated with same-sex attraction and partners among both sexes. In the latter study, size of home town also showed a positive association with having had a same-sex partner. Möllborn and Everett (2015) found the same for men but not for women. Although similar differences were not reported in some more recent studies (England et al., 2016), the findings above support the notion that exposure to new ideas through education or environment may contribute to an increase in the prevalence of minority sexual orientation.

As noted in the introduction, there are only a few studies that explore parenthood intentions among people with minority sexual orientation. Using nationally representative data from the 2002 US National Survey of Family Growth (NFSG), Riskind and Patterson (2010) investigated parenting intentions, desires, and attitudes of childless lesbian, gay and heterosexual individuals aged 15 to 44 years. They found that gay men and lesbian women were less likely than matched heterosexual peers to express desire for parenthood. Furthermore, gay men (but not lesbian women) who desired to become parents were less likely to express the intention to have children. However, gay and lesbian participants endorsed the value of parenthood just as strongly as did heterosexual participants. A follow-up study involved a more recent NSFG sample that also included bisexual individuals (Riskind & Tornello, 2017). This study showed that bisexual women and men’s parenting desires and intentions more closely resembled those of heterosexual individuals than they did of lesbian and gay individuals.

Tate et al. (2019), using data from the US National Survey of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), analysed intentions for parenthood, ideal family size and predictors of parenting intentions as a function of gender and sexual orientation. The authors observed that a large majority of childless heterosexual participants intended to become parents, but this was the case for just over half of childless lesbian and gay participants. Furthermore, among those who intended to become parents, lesbian and gay individuals reported smaller intended family sizes than their heterosexual peers. However, somewhat different results are reported by Simon et al. (2018). Based on a convenience sample of childless women, recruited through advertisements posted on family planning and family creation websites and social media groups, they found no differences in sexual orientation in respondents’ desires and intentions to have children, or in their idealisation of parenthood and perceptions of parental self-efficacy.

Existing European studies of fertility intentions among sexual minorities have drawn their evidence from small-scale convenience samples. Baiocco and Laghi (2013) found that childless lesbian and gay individuals in Italy are less likely than their heterosexual peers to express parenting desires and intentions. Kranz et al. (2018) showed that gay participants in Germany have weaker fathering desires and intentions than their heterosexual counterparts. Gato et al. (2020) analysed the anticipation of parenthood among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual women and men in Portugal. Their findings indicate that lesbian women and gay men are less likely to intend to have children than heterosexuals, while bisexual individuals are not significantly different from any of the other groups.

Meyer (2003) proposed the minority stress theory as a conceptual framework to explain disproportionately poorer mental health outcomes among sexual minority groups. The theory suggests that specific disadvantages accumulate for sexual minorities due to interpersonal and institutional discrimination. With respect to fertility, institutional discrimination may include laws banning same-sex marriage, same-sex partnerships or joint adoption by same-sex parents; limited access to reproductive health services; etc. Interpersonal discrimination ranges from non-acceptance to overt hostility from family, social network members and strangers. Such influences constitute chronic stressors that can interfere with the wellbeing of the individual, as well as coping processes. According to Meyer (2003), minority stress is caused not only by objective acts of discrimination, but also by expectations of such acts, and more subjective feelings that can be conceived as internalised stigma. These mechanisms are used to explain lower parenthood intentions among sexual minority groups (Baiocco & Laghi, 2013; Gato et al., 2020; Riskind & Tornello, 2017).

The literature suggests that the perception of costs is an important factor which is negatively associated with parenthood intentions (Liefbroer, 2005). In case of sexual minority, the costs associated with assisted reproduction and/or adoption make entry into parenthood more costly in terms of effort and economic resources than for heterosexual couples (Blanchfield & Patterson, 2015; Riskind et al., 2013; Tate et al., 2019). In fact, Tate and Patterson (2019) show that sexual minority women viewed parenthood as having a considerable cost, and that this alone accounted for a large part of differences in parenthood aspirations between them and their heterosexual counterparts. This plausibly holds to an even greater extent for men, given their much lower (relative to women) fertility rates within same-sex marriages (e.g. Kolk & Andersson, 2020).

The Estonian Context

The European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA-Europe) Rainbow index (2020) ranks Estonia 23rd among 49 European countries. While lagging behind Scandinavian and many Central and Southern European countries, the situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex (LGBTI) rights in Estonia is nonetheless one of the best among Eastern European countries, meaning that there has been a more rapid change in how LGBTI people are seen and treated compared to in other countries in the region. The rankings are based on a wide range of indicators showing how the laws and policies of each country impact on the lives of LGBTI people, varying from gross violations of human rights and discrimination to respect of human rights and full equality of sexual minority groups. Compared to the average European country Estonia is judged to be advanced in civil society space, but lagging behind in hate crime, hate speech and asylum rights of LGBTI people. When it comes to family issues, Estonia is ranked under average, meaning that there are family-related rights that are not equally accessible for LGBTI people compared to heterosexuals.

Family-related rights mainly include the possibilities to marry or form legal partnerships and to become a parent, either via adoption, medically assisted insemination, etc. The Estonian Parliament adopted the Registered Partnership Act in 2014. The Act came into force on 1 January 2016, but the legislation implementing the Registered Partnership Act has not yet been adopted. This means that same-sex couples have limited rights and protections, though the Supreme Court decisions in individual cases have constantly widened the rights. Drafting the act brought along sharp political and societal disagreements, but recent public opinion surveys show that the share of supporters of the act is on the rise (Turu-uuringud AS, 2019, 2021). In 2021, 64% of the respondents supported the act (49% in 2019). There is higher support among younger age groups (82% among 20–29-year-olds) and among the Estonian-speaking population (72%) compared to the other, mainly Russian-speaking population (47%).

Estonian law does not allow same-sex couples to jointly adopt or have medically assisted insemination as a couple. However, according to the Registered Partnership Act and Family Law Act, it is possible to adopt a biological or adopted child of the same-sex partner if the child was born or adopted by the other partner before the partnership agreement was concluded. Thus, the regulations provide some means for same-sex partners to legally start a family and have children, but executing parenting rights is considerably more difficult for same-sex couples than for heterosexuals. Child-related issues are also among the most sensitive ones, according to the public opinion surveys (Turu-uuringud AS, 2019, 2021). Only less than half of the respondents support same-sex couples’ rights to adopt, even though the change in attitudes has been quite significant—from 27% in 2019 to 40% in 2021. Here the attitudes differ greatly among the respondents’ sex and age. Women and young people under 30 years of age tend to agree that same-sex partners should have adoption rights; men and older respondents tend to disagree.

Overall, the attitudes towards LGBT people have improved quite rapidly in recent years in Estonia. Over the last ten years, the Estonian Human Rights Centre has conducted five public opinion surveys (in 2012, 2014, 2017, 2019 and 2021) regarding LGBT rights, and for the first time the results show that more than half (53% in 2021) of the respondents consider homosexuality completely or rather acceptable. The most open in these matters are 15–19-year-olds, so it is likely that the trend will continue. At the same time, LGBT people in Estonia still face many legal obstacles and negative attitudes, which makes it difficult to exercise their rights in different life spheres, including parenting, equally to heterosexuals.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

In this study, we pose three research questions. First, what is the sexual orientation of contemporary Estonian adolescents aged 16 to 19 years. Second, what are the factors associated with having a minority sexual orientation. Third, what is the relationship between sexual orientation and fertility intentions. The literature, previous findings and the context lead us to the following hypotheses.

Our first hypothesis (H1) is that the diversity of sexual orientation among adolescents is relatively high in Estonia, although we do not make numerical predictions. This hypothesis draws on the understanding according to which the increase in diversity of sexual orientation can be viewed as a companion to increased diversity of family forms and dynamics during the era of the second demographic transition (Lesthaeghe, 2020; Van de Kaa, 1987). New patterns of family dynamics emerged relatively early in Estonia (Katus et al., 2008; Puur et al., 2016). The assertion is also guided by earlier findings which show that compared to other countries in the region, the proportion of adults reporting same-sex attraction is relatively high (Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 2003).

We anticipate minority sexual orientation to be associated with factors pertaining to socio-demographic characteristics and childhood environment. More specifically, our second hypothesis (H2) posits that the odds of minority orientation are higher among subgroups which are more exposed/open to new ideas and behaviours (Butler, 2000; Laumann et al., 1994). Our third hypothesis (H3) posits that minority sexual orientation tends to be associated with unfavourable conditions in the childhood home (Roberts et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2019).

Our fourth hypothesis (H4) is that adolescents with minority orientation exhibit smaller intended family size than their majority peers. The hypothesis draws on evidence from earlier US and European studies reviewed above. Limited legal provisions for same-sex couples in Estonia make this outcome plausible. Guided by the review of empirical evidence by Savin-Williams and Vrangalova (2013), we expect that differences from heterosexuals will also be observed in the intermediate group, with moderate attraction to their own sex (hypothesis H5).

Data and Methods

The data for this study come from the Estonian Youth Family Survey commissioned by the Estonian Family Foundation from March to April 2020. The survey collected information on education, employment, family of origin, health, wellbeing, life goals and plans for the future; altogether the survey questionnaire comprised 57 questions. A probability sample of adolescents aged 16–19 was drawn from the population register.Footnote 1 Data were collected online with a response rate of 36%. After data collection, the responses were weighted in order to match the structure of target population by sex, age and region of residence. Further information about the survey is available from report compiled by the survey agency (Turu-uuringud AS, 2020).

In this article, we analyse the association between sexual orientation and fertility intentions, and the factors associated with sexual orientation. Self-reported sexual orientation was used a five-grade scale of sexual attraction. The respondents were required to answer the question, “Which of the following items best describes your sexual attraction (orientation)?” The response categories were ‘Only to men’, ‘Mainly to men’, ‘To both sexes equally’, ‘Mainly to women’ and ‘Only to women’; additional response categories for those who did not choose the main ones were ‘Other’, ‘Do not know’ and ‘Do not want to answer’. Similar scale of sexual attraction has been used in many studies of adolescents and young adults (Austin et al., 2009; Katz-Wise et al., 2017; Remafedi et al., 1992). Such scales are reported to have low item-specific non-response rates (Saewyc et al., 2004) and good reliability over time (Ott et al., 2011).

The survey also enquired about same-sex sexual experiences. The respondents were asked the question “Have you had any sexual experience (intercourse, petting) with a partner of your own sex?”, with answer categories ‘No’, ‘Once’ and ‘Several times’. However, this question proved less useful for our study as less than half of the respondents (44.6%) had been sexually active. The distribution of respondents by sexual attraction and same-sex experience is presented in the next section.

Fertility intentions were measured in terms of lifetime intentions using the question “How many children you would like to have?” The response categories included ‘None’, ‘One’, ‘One or two’, ‘Two’, ‘Two or three’, ‘Three’, ‘Three or four’, ‘Four’, ‘Four or five’, ‘Five or more’ and ‘Do not know’. We code the answer ‘One or two’ to be 1.5, ‘Two or three’ to be 2.5 and so on. This means that the variable is not an integer.

The analysis is structured in three parts. First, the sexual orientation among our study population is examined using descriptive measures (distribution of respondents by sexual orientation and same-sex experience).

Second, binomial logistic regression models are employed to analyse factors associated with having a minority sexual orientation. The dependent variable distinguishes between respondents who are only attracted to the opposite sex, and those who express varying degrees of attraction to their own sex, since the cell sizes are too small for some categories. For the same reason, modelling results are presented for male and female respondents combined. The choice of explanatory variables, which fall into two groups, is based on the literature review. The first group includes some of the main socio-demographic characteristics of respondents such as sex (male, female), area of residence (rural area or small town, large town, capital city) and ethnicity (Estonian, other). The second group comprises variables that characterise the respondents’ childhood environments. This group includes number of siblings, maternal education (secondary or lower, tertiary), atmosphere in the parental home (warm and friendly, slight quarrels from time to time, severe and lasting conflicts), experience of family violence in the parental home (yes, no), frequent consumption of alcohol in the parental home (yes, no) and (low) satisfaction with economic conditions in the parental home (ordinal measure). Descriptive statistics and additional information for variables used in the analysis are shown in Online Appendix (Table A1).

Third, descriptive measures and linear regression models are applied to investigate the relationship between lifetime fertility intentions and sexual orientation. The dependent variable is the number of intended children. As mentioned, this variable is not an integer, which excludes the possibility of modelling it with a model from the Poisson family (standard Poisson, zero-inflated Poisson, negative binomial), which have also been used in the literature to model number of children—intended or actual (for example: Engelhardt, 2004; Harber-Aschan et al., 2022; Wilson, 2019). The main independent variable reflects the sexual orientation of respondents based on the attraction measure described above. The choice of control variables is guided by the previous studies of fertility intentions (Miettinen et al., 2011; Philipov et al., 2006; Puur et al., 2018). The control variables include sex (male, female), area of residence (rural area or small town, large town, capital city), ethnicity (Estonian, other), number of siblings, maternal education (secondary or lower, tertiary), experience of parental divorce/separation (yes, no, parents never lived together), self-rated health (very good or good, satisfactory, bad or very bad) and mental distress (low, medium, high). Descriptive statistics and additional information for variables used in the analysis of intended number of children are shown in Online Appendix (Table A2).

Results

Sexual Orientation

Table 1 displays the distribution of answers to the question about sexual attraction. The results reveal a considerable diversity of sexual orientation among Estonian adolescents. Three-fourths (75.9%) of the respondents reported attraction only to the opposite sex. The second largest group (13.2%) comprises those who feel attraction mainly (though not exclusively) to the opposite sex. The proportion of respondents with equal interest in the opposite and same sex is 4.2%. Adolescents who are mainly or only attracted to their own sex constitute a small group, 1.2% and 1.0% of the respondents, respectively. Altogether, close to one-fifth (19.6%) of respondents reported some attraction to their own sex. Among women, the proportion is higher, exceeding one-quarter (27.2%) of the respondents. Behind the observed gender difference are those respondents who described themselves as attracted mainly (though not exclusively) to the opposite sex, or to both sexes equally.

A small proportion of respondents (0.5%) chose the open-ended category ‘other’. A closer look at their answers shows that a majority of adolescents in this group are self-defined as asexual, i.e. individuals who do not find others sexually appealing and lack sexual desire. In the literature, asexuality is sometimes considered a separate category of sexual orientation, distinct from heterosexuality, homosexuality or bisexuality (Bogaert, 2012). 3.9% of the respondents opted out of reporting their sexual attraction by answering ‘do not know’, or refusing to answer. In studies focussing on the association between sexual orientation and individual outcomes, the latter respondents are often treated as missing values, and excluded from the analysis. In this study, we decided to include them in order to find out whether their fertility intentions are distinct from those of other sexual orientation groups.

The survey also enquired about same-sex sexual experiences. However, this aspect is less relevant to our study population, as less than half of the respondents are sexually active. Table 2 shows that more than one-tenth (11%) of sexually active adolescents have had a same-sex experience. Of those, nearly half reported repeated experience with a partner of their own sex. If we consider all respondents, irrespective of whether they are sexually active or not, then the proportion of adolescents with same-sex experiences decreases to 7%. A small fraction of respondents (2.1%) that have been sexually active did not answer the question about experiences with a same-sex partner. Similar to same-sex sexual attraction, same-sex sexual experience appears more frequent among female respondents.

For further insight into the above aspects of sexual orientation, we explored the association between them. Among sexually active adolescents who answered questions about sexual attraction and experience, the relationship between two variables appears relatively strong. Of adolescents who are only attracted to the opposite sex, a small fraction (4.1%) reported having had a sexual encounter with a partner of their own sex. Among respondents who are mainly attracted to the other sex, the prevalence of same-sex sexual experiences increases to one-quarter (26.4%). Further, more than half (59.1%) of adolescents who reported equal interest towards the opposite and their own sex have experience with a same-sex partner. Finally, of respondents who are attracted mainly or only to the same sex, 85% reported same-sex sexual experience. A cross tabulation of sexual attraction and experience is shown in Online Appendix (Table A3). In the concluding section, we discuss how our results relate to those of other studies.

Factors Associated with Sexual Orientation

In this section, we examine the factors associated with minority sexual orientation defined on the basis of sexual attraction. We estimate a series of binomial logistic regression models. Due to relatively small number of respondents with different non-majority orientation, we combine them into a single group and present the results for male and female respondents combined.

The outcome variable is set to 1 if the respondent reported attraction only to the same sex, mainly to the same sex, to the opposite and same sex equally, or mainly to the opposite sex; it is set to 0 if the respondent is attracted only to opposite sex. Excluded from the analysis are the respondents who opted out of disclosing their sexual orientation, or chose response category ‘other’. The explanatory variables included the main socio-demographic characteristics of respondents (sex, area of residence and ethnicity) and variables that characterise family background and childhood environment (number of siblings, maternal education, atmosphere in the parental home, experience of family violence in the parental home, consumption of alcohol in the parental home and satisfaction with economic conditions in the parental home).Footnote 2

In order to provide insight into the role of these factors, we estimate two main effects models. The first model produces non-adjusted estimates for the effects of independent variables, with one variable at a time inserted into the model; the second model includes the full complement of independent variables, and produces the adjusted estimates. Both the non-adjusted and adjusted results presented in Table 3 indicate that girls exhibit 2.7 times higher odds of minority sexual orientation compared to boys. Residence in a capital city or large town is also associated with higher odds of minority sexual orientation, but the difference from the reference category is about twice smaller. The difference between Estonians and other ethnic groups (mostly Russians) is not statistically significant.

With regard to childhood conditions, we identified a number of factors that appear to be significantly correlated with minority sexual orientation. A stressful atmosphere in the parental home tends to be associated with a higher likelihood of minority sexual orientation. Adolescents who reported slight quarrels from time to time in their parents’ home have 1.8 times higher odds of minority orientation than peers who described the atmosphere in their family of origin as warm and friendly. Severe/lasting conflicts in childhood home are associated with even higher odds of same-sex orientation.

Additional evidence of a relationship between childhood disadvantage and minority sexual orientation comes from results concerning the experience of familial violence. Among adolescents who encountered aggressive behaviour and domestic violence in their parental homes, the odds of minority orientation appear 1.4 times higher compared with their peers who did not report such experiences. Our results show an association between frequent alcohol consumption in the parental home and the incidence of minority orientation. Respondents who witnessed alcohol consumption several times a week or more often exhibit 1.5 times higher odds of minority orientation than those who reported less frequent consumption of alcohol. We also found a moderate relationship between low satisfaction with the financial situation of the parental household and minority sexual orientation. However, in the adjusted model, the parameter effect loses statistical significance. Notably, this is the only independent variable in our models that undergoes such a change. A stepwise inclusion of variables (not shown) reveals that the loss of statistical significance occurs when a covariate describing the atmosphere in childhood home is added to the model.

The evidence above suggests that unfavourable conditions in the parental home are associated with childhood disadvantage. However, it would be one-sided to relate minority sexual orientation solely to a disadvantaged background. Such a generalisation is contradicted by findings on parental education: the adolescents whose mothers have tertiary education show 1.5 times higher odds of minority orientation compared to their peers with less educated mothers. In the exploratory models, we found a similar effect associated with father’s education. Finally, our results reveal an inverse relationship between growing up in a larger family and minority sexual orientation.

The Association Between Fertility Intentions and Sexual Orientation

Table 4 shows considerable differences in parenthood intentions by sexual orientation. The intended number of children appears highest among youngsters who are only attracted to the opposite sex. In this group, the mean number of children intended is close to replacement level. The second group, characterised by moderate same-sex orientation, shows intended family sizes 8% smaller than the first one.Footnote 3 Adolescents in the third group, who are equally attracted to the same and the opposite sex, intend to have 34% less children than their peers in the first group. A closely similar level of intended fertility is found among respondents who are attracted mostly, though not only, to their own sex. Finally, the respondents attracted only to their own sex have the lowest fertility intentions, approximately half of the replacement level.

Table 4 also presents the intended number of offspring of respondents who were not willing or able to answer about their sexual attraction. With intended fertility approximately one-fifth lower than that of their counterparts who are only attracted to the opposite sex, adolescents with missing substantive answers are distinct from the majority group. This finding lends support to the assertion that the lack of substantive answer may indicate a minority sexual orientation that the respondent is not prepared to disclose.Footnote 4

The patterns described above are corroborated by the proportion of respondents who intend to have any children (the right column of Table 4). This suggests that the association between the intended number of children and sexual orientation is largely due to intended childlessness.

Before drawing conclusions about the relationship between fertility intentions and sexual orientation, it is necessary to check whether the above differences between majority and minority groups are statistically significant. For this purpose, we estimate linear regression models with intended number of children as an outcome variable. The main independent variable is based on survey questions about sexual attraction; given the small number of respondents who are mainly or only attracted to the same sex, we merge these two groups. We estimate non-adjusted and adjusted models. The non-adjusted model produces estimates for the effects of independent variables, with one variable at a time inserted into the model. In the adjusted model, sex, area of residence, ethnicity, number of siblings, maternal education, experience of parental divorce/separation, and physical and mental health measures are added as controls.Footnote 5

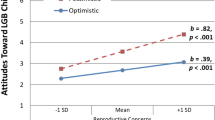

The modelling results presented in Table 5 reveal statistically significant intergroup differences corroborating the above pattern in descriptive measures. In the non-adjusted model, attraction mainly (but not exclusively) to the opposite sex is associated with a decrease in the intended number of children by 0.19 compared to the reference group. Among respondents who are equally attracted to their own and the other sex, the difference from the reference group amounts to 0.71. The respondents attracted mainly or only to the same sex exhibit the largest gap in intended number of offspring (0.82). The p values suggest that the difference from the reference category (respondents attracted only to opposite sex) is statistically significant among all orientation groups.

The inclusion of control variables in the model results in a moderate decrease in the effect size among respondents who are attracted mainly to the opposite sex (from − 0.19 to − 0.13), and those who are equally attracted to their own and the opposite sex (from − 0.71 to − 0.67). In the case of the first group, we observe a decrease in statistical significance below a p < 0.05 level. By contrast, among the respondents who are attracted mainly or only to the same sex, the parameter effect slightly increases rather than decreases in the adjusted model (from − 0.82 to − 0.86). The similarity of the results obtained from non-adjusted and adjusted models suggests that the association between fertility intentions and sexual orientation is relatively independent from the control variables included in the model.Footnote 6

The modelling results shown in Table 5 also corroborate descriptive findings for respondents who did not disclose their sexual attraction. In both non-adjusted and adjusted models, belonging to the latter group entails a statistically significant decrease in the intended number of children compared to the reference group.

Notably, in the adjusted model, the effects of control variables are smaller than those found for sexual orientation (Table 3). Girls show somewhat higher fertility expectations than boys, while adolescents living in the capital city intend to have a smaller family than their counterparts living in small towns or rural areas. The latter also holds for adolescents of other ethnic groups compared to their Estonian peers, in line with the pattern of ethnic fertility differences in the country (Puur et al., 2017). Differences associated with area of residence and ethnicity are not significant at a p < 0.05 level. With regard to characteristics of parents and parental home, the number of siblings and mother’s tertiary education are positively correlated to intended family size. In contrast, the experience of parental divorce is associated with somewhat lower intended fertility. Likewise, bad or satisfactory self-rated health, and high or medium levels of mental distressFootnote 7 tend to be associated with significant decrease in the number of expected children. Differences associated with the number of siblings, mother’s education, parental divorce, self-rated health and mental distress are all significant at a p < 0.05 level.

In the Appendix, we present additional estimates for the intention to have any children. The results show that the respondents who reported attraction to their own sex have lower parenthood intentions, relative to their counterparts in the reference group, attracted only to the opposite sex (Table A4).

Summary and Discussion of the Findings

In this article, we investigated the sexual orientation of adolescents aged 16 to 19 years, the factors associated with it, and the relationship between sexual orientation and fertility intentions, based on a recently conducted youth survey in Estonia. The contribution of our study is derived from two sources. First, as part of rapidly expanding literature on experiences of sexual minorities in various life domains, social scientists have investigated the size and characteristics of sexual minority populations, the dynamics of same-sex partnerships, parenting and retirement strategies, and other topics. However, there is much less research on childbearing intentions of sexual minority groups. Furthermore, existing studies of fertility intentions among sexual minority populations are often based on convenience samples that hamper generalisation and do not analyse the entire spectrum of sexual orientation (Gato et al., 2020; Kranz et al., 2018; Simon et al., 2018; Tate et al., 2019). Second, family and fertility surveys tend to exclude (late) adolescents, as most of them have not yet started a family. However, intentions for parenthood and family size in this age group can provide insight into future fertility trends.

A number of findings emerged from this study. In line with our first hypothesis (H1), we found that the diversity of sexual orientation is relatively high among adolescents in Estonia. Altogether one-fifth of the respondents reported some degree of attraction to their own sex. However, the proportion of respondents who are attracted to both sexes equally, and those attracted mainly or only to the same sex was much smaller, 4.1% and 2.2%, respectively. Comparison with a survey conducted at the beginning of the twenty-first century (Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 2003) shows a 1.8-fold increase in the proportion of respondents who expressed some degree of same-sex attraction. The increase is also evident in comparison with a more recent survey conducted in 2014 (Lippus et al., 2015). Since then, the proportion of women aged 16–19 who choose response categories other than ‘attraction to opposite sex’ has grown 1.5 times. The largest contribution to the overall increase in the prevalence of minority sexual orientation comes from the group which exhibits a moderate attraction to their own sex. However, in relative terms, the growth has been even throughout the entire continuum of same-sex attraction.

Variation in study populations, sampling procedures and the operationalisation of sexual orientation prevent us from making direct comparisons to situation in other settings. Nevertheless, the diversity of sexual orientations observed in our study is in accord with Savin-Williams and Ream (2007), who suggested that if the definition included individuals who had sex with both sexes, had some degree of same-sex attraction, or had at least one of the two, the proportion of individuals with minority sexual orientation would reach to nearly one-fifth of the population. The above evidence pertaining to increase in the prevalence of same-sex attraction is corroborated by several US studies that have documented an upward trend in the share of people reporting having had same-sex partners in the 1990s and 2000s (Butler, 2000, 2005; Turner et al., 2005; Twenge et al., 2016).

Following our second hypothesis (H2), we anticipated higher odds of minority sexual orientation among subgroups which can be regarded as more exposed and more open to new ideas and behaviours, placing more significance on having new experiences, including experimenting with same-gender sex during youth and early adulthood (Wienke and Whaley 2015). The results support our hypothesis. We found a higher likelihood of minority orientation among adolescents living in the capital and large towns, as well as among those with tertiary educated parents. Thus, the educational gradient in minority sexual orientation bears resemblance to that observed during the rise of divorce (Goode, 1993; Matysiak et al., 2014), and the spread of consensual unions in a number of countries (Lesthaeghe, 2020). Indeed, like entering a consensual union and having a divorce during the early stages of the second demographic transition, exhibiting attraction towards one’s own sex presupposes a considerable degree individual autonomy as the behavioural pattern runs counter to the prevailing cultural code.

Our third hypothesis (H3) posited the association between minority sexual orientation and less favourable living situations in the parental home. The results confirm this assertion. The models estimated for minority orientation revealed a statistically significant association with stressful domestic atmosphere, the experience of domestic violence and frequent alcohol consumption in the parental home. These findings corroborate previous studies, which have found a relationship between minority sexual orientation, on the one hand, and adverse early-life conditions and childhood maltreatment, on the other hand (Martinez & McDonald, 2021; Roberts et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2019). The above results show a similarity with the pattern of disadvantage, a theoretical perspective that relates the rise of new family and fertility patterns, such as consensual unions and childbearing outside marriage, to unfavourable situation among the poorer segments of the population (Perelli-Harris & Gerber, 2011; Perelli-Harris et al., 2010).

In accord with our fourth hypothesis (H4), the results show a statistically significant negative relationship between minority sexual orientation and fertility intentions. With regard to effect size, our findings corroborate an earlier Italian study in which the sexual orientation proved to be the strongest predictor of parenthood intentions (Baiocco & Laghi, 2013). Unlike previous studies, we found intended family size to be smaller compared to heterosexuals, not only in the groups with distinct same-sex orientation, but also among an intermediate group with moderate attraction to their own sex, thus confirming our fifth hypothesis (H5). This result lends support to Savin-Williams and Vrangalova (2013), who proposed to distinguish the individuals mainly but not exclusively attracted to the opposite sex.

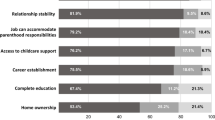

How do we explain these differences? Due to limited information collected in the youth survey, we are unable to thoroughly test the mechanisms underlying them. However, it is interesting to note that the answers to a question on more general fertility ideals—how many children an average Estonian family should have—showed a much smaller difference based on reported sexual attraction. In the models, shown in Online Appendix (Table A5), only the respondents who were equally attracted to both sexes reported a significantly smaller number of children an average Estonian family should have, compared with their peers in the reference group (attracted only to the opposite sex). Furthermore, the difference from the reference group was much smaller than that reported in Table 5. This suggests that lower personal fertility intentions among the minority sexual orientation groups plausibly stem from a less optimistic perception of their individual life chances rather than from a generally lower value attached to parenthood. Our results provide some insight into the role of mental distress in producing this outcome. The inclusion of a control for mental distress did not alter the results for the association between sexual orientation and intended family size. This implies that mental distress is probably not among the central mechanisms that account for lower parenthood intentions among sexual minority groups, a conclusion which is at odds with the assertion that can be derived from the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003).

A few other findings, although not directly related to our hypotheses, deserve discussion. First, we found markedly elevated odds of minority sexual orientation among women. A closer examination of the data revealed that this difference is due to the fact that women were more likely than men to report moderate attraction to their own sex, as well as equal attraction to both sexes. The proportions of men and women who are mainly or only attracted to their own sex are quite similar (2.7% of men and 1.9% of women). A similar pattern has been found in different settings. For instance, in Norway and New Zealand, young women were far more likely than young men to endorse same-sex attraction (Dickson et al., 2003; Wichstrøm & Hegna, 2003). Several US studies have reported greater increases in same-sex sexual behaviour and attraction in women compared to men (England et al., 2016; Mishel et al., 2020; Phillips II et al., 2019). There is also growing evidence of the feminisation of same-sex marriages (Andersson & Noack, 2010; Andersson et al., 2006; Chamie & Mirkin, 2011; Kolk & Andersson, 2020; Ross et al., 2011). Some authors suggest that the observed pattern stems from the greater impact of social environment on female rather than male sexual orientation, whereas others speculate that changes in norms about gender and sexual behaviour have intersected in a way that provides more opportunities for women than men to have same-sex sexual relations (Bailey et al., 2016; Katz-Wise, 2015).

Second, we provided new evidence about respondents who were unsure about or unwilling to disclose their sexual orientation. To date, only a few studies have investigated individuals who belong to this group. Two longitudinal studies on adolescents reported that the respondents who were unsure about their sexual orientation tended to identify themselves heterosexual later in life (Ott et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2021). A third study based on the German Socioeconomic Panel Survey found that a majority of respondents who provided non-substantial answers when asked about their sexual orientation were classified as heterosexual based on their partnership information (Kühne et al., 2019). In our study, the respondents who opted out of disclosing their sexual orientation proved distinct from the majority group in their childbearing intentions, being similar to their counterparts who expressed equal interest in both sexes.

Finally, this study is not without limitations. Although a robust association between sexual orientation and fertility intentions was found, our data are not rich enough to test the various possible explanations underlying the relationship, as mentioned already. Based on the literature, we can speculate that the disparity in fertility intentions between respondents with majority and minority sexual orientation stems from a variety of factors, ranging from differences in expected emotional enrichment brought by children to perceived costs and difficulties associated with having a child (Baiocco & Laghi, 2013; Gato et al., 2017; Goldberg et al., 2012; Tate et al., 2019).

Another limitation arises from the fact that childhood conditions in our study were measured retrospectively. This carries a risk of recall bias, and prevents a causal interpretation of results on the relationship between childhood context and minority sexual orientation. Nonetheless, our findings on the role of childhood context do not stem from a single variable, but relate to a number of different independent variables. Furthermore, none of these focussed specifically on the maltreatment of respondent, but reflects the situation in the parental home in a more general manner. This reduces, though not eliminates the possibility found in some studies, that the relationship between childhood context and minority orientation is driven by the adverse reaction of parents and other family members to a child’s gender non-conformity or minority sexual orientation (Alanko et al., 2010; D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; Roberts et al., 2012; Saewyc et al., 2006).

Further, the sample used in this study is relatively small. This did not allow us to analyse women and men separately and to systematically distinguish different minority orientation groups in the analyses of factors associated with minority sexual orientation. Due to this limitation, our study does not show how the factors associated with minority sexual orientation vary across adolescents with different degrees of attraction to the same sex. With these limitations, we were able to show a considerable gender difference in the odds of minority sexual orientation. Our results also demonstrate that differences in fertility intentions exist throughout the entire continuum of sexual orientation. Our measure of sexual orientation is based on sexual attraction to the opposite and own sex as reported by the respondents. We are aware that this choice is at odds with the complexity of sexual orientation, which also includes behaviour and identity dimensions. However, attractions are considered to be the most valid way of measuring self-reported sexual orientation, because sexual attractions motivate behaviour and identity (Bailey et al., 2016; Saewyc et al., 2004). As reported in earlier sections, supplementary analyses drawing on behavioural measures yielded results that are consistent with those based on sexual attraction.

Lastly, one has to bear in mind that our study population consisted of adolescents in their late teens. Thus, it is unclear how their sexual orientations might change as they approach their late twenties and thirties. The existing research suggests that sexual orientation may change in early adulthood, and more so for women (Hu et al., 2016; Ott et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2021). There is also evidence that family size intentions are not stable, but are adjusted as people age (Heiland et al., 2008; Liefbroer, 2009). Thus, it has to be ascertained by future research what the relationship between sexual orientation and fertility intentions will be when today’s adolescents reach their prime childbearing years.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we believe that some important conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, based on a representative sample, it demonstrates that there is a considerable diversity of sexual orientation among contemporary adolescents. Second, it shows marked disparity in fertility intentions associated with minority sexual orientations. Remarkably, the difference from the majority population can also be observed among the group with moderate attraction to their own sex. Finally, we would like to point out that although there are only very few studies on how differences in fertility intentions associated with sexual orientation are evolving over time (Riskind & Tornello, 2017), disparities in health and health behaviour have proven rather persistent, despite increased public acceptance and the implementation of policies to support equality and outlaw the discrimination of sexual minorities (Goodenow et al., 2016; Liu & Rezcek, 2021; Philips II et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2018). This suggests that the importance of childbearing intentions and behaviour among the sexual minority populations for overall fertility trends may increase and calls for more population-based research on sexual minority populations, including reliable and internationally comparable estimates on the size, characteristics and reproductive behaviour of these populations.

Notes

In the data, we have a small number of respondents older than 19 as some participants turned 20 between sampling and data collection.

In the exploratory stage, we run models with some additional independent variables (age of the respondent, experience of parental divorce or separation, etc.). As none of these covariates exhibited a statistically significant association with our outcome measure, they are not included in the final model.

8% = (1–1.89/2.06) × 100%.

In order to check the validity of the results based on sexual attraction, we also explored the average intended number of children in sexually active respondents grouped by same-sex sexual experience. We found that those with no same-sex experience have intended fertility (2.05 children) similar to their peers who are only attracted to the opposite sex. Adolescents with single and repeated same-sex experiences have markedly lower numbers of intended children, on average 1.85 and 1.48 children, respectively.

In the exploratory analysis, we fitted models with additional control variables, which had proven important as factors related to the sexual minority orientation (atmosphere, experience of family violence, consumption of alcohol and satisfaction with economic conditions in the parental home). As none of these covariates showed a significant effect on the intended number of offspring, they are not included in the final model.

We also estimated some additional models for sexually active adolescents, with same-sex sexual experience as the main independent variable and the same control variables. The results showed a significant negative relationship between same-sex sexual experience and the intended number of children (linear regression coefficient -0.35 in the adjusted model, p-value < 0.01).

The methodology of Mental Health Inventory 5 (MHI-5) mental distress index used is based on Veit and Ware (1983).

References

Alanko, K., Santtila, P., Harlaar, N., Witting, K., Varjonen, M., Jern, P., Johansson, A., von der Pahlen, B., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2010). Common genetic effects of gender atypical behavior in childhood and sexual orientation in adulthood: A study of Finnish twins. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(1), 81–92.

Andersson, G., & Noack, T. (2010). Legal advances and demographic developments of same-sex unions in Scandinavia. Zeitschrift Für Familienforschung/journal of Family Research, 22, 87–101.

Andersson, G., Noack, T., Seierstad, A., & Weedon-Fekjaer, H. (2006). The demographics of same-sex marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography, 43(1), 79–98.

Austin, S. B., Ziyadeh, N. J., Corliss, H. L., Rosario, M., Wypij, D., Haines, J., Camargo, C. A., Jr., & Field, A. E. (2009). Sexual orientation disparities in purging and binge eating from early to late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), 238–245.

Bailey, J. M., Vasey, P. L., Diamond, L. M., Breedlove, S. M., Vilain, E., & Epprecht, M. (2016). Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17(2), 45–101.

Baiocco, R., & Laghi, F. (2013). Sexual orientation and the desires and intentions to become parents. Journal of Family Studies, 19(1), 90–98.

Bennett, N. G. (2017). A reflection on the changing dynamics of union formation and dissolution. Demographic Research, 36(12), 371–390.

Biblarz, T. J., & Stacey, J. (2010). How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(1), 3–22.

Billy, J. O., Tanfer, K., Grady, W. R., & Klepenger, D. H. (1993). The sexual behaviour of men in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives, 25(2), 52–60.

Blanchard, R. (2018). Fraternal birth order, family size, and male homosexuality: Meta-analysis of studies spanning 25 years. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 1–15.

Blanchard, R., & Ellis, L. (2001). Birth weight, sexual orientation and the sex of preceding siblings. Journal of Biosocial Science, 33(3), 451–467.

Blanchfield, B. V., & Patterson, C. J. (2015). Racial and sexual minority women’s receipt of medical assistance to become pregnant. Health Psychology, 34(6), 571–579.

Bogaert, A. F. (2012). Understanding asexuality. Rowman and Littlefield.

Brewer, P. R., & Wilcox, C. (2005). The polls–trends: Same-sex marriage and civil unions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(4), 599–616.

Butler, A. C. (2000). Trends in same-gender sexual partnering. Journal of Sex Research, 37(4), 333–343.

Butler, A. (2005). Gender differences in the prevalence of same-sex sexual partnering: 1988–2002. Social Forces, 84(1), 421–449.

Calzo, J. P., Mays, V. M., Björkenstam, C., Björkenstam, E., Kosidou, K., & Cochran, S. D. (2017). Parental sexual orientation and children’s psychological well-being: 2013–2015 national health interview survey. Child Development, 90(4), 1097–1108.

Carvalho, H. W., Dall’Agnol, S. C., & Lara, D. R. (2017). Trends in sexual orientation in Brazil. Psico, 48(2), 89–98.

Chamie, J., & Mirkin, B. (2011). Same-sex marriage: A new social phenomenon. Population and Development Review, 37(3), 529–551.

Corliss, H. L., Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2002). Reports of parental maltreatment during childhood in a United States population-based survey of homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual adults. Child Abuse and Neglect, 26(11), 1165–1178.

D’Augelli, A. R., & Grossman, A. H. (2001). Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16(10), 1008–1027.

Del Giudice, M., Gangestad, S. W., & Kaplan, H. S. (2015). Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 88–114). Wiley.

Diamond, L. M. (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110(1), 173–192.

Dickson, N., Paul, C., & Herbinson, P. (2003). Same-sex attraction in a birth cohort: Prevalence and persistence in early adulthood. Social Science and Medicine, 56(8), 1607–1615.

Ellis, B. J. (2004). Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 920–958.

Engelhardt, H. (2004). Fertility intentions and preferences: Effects of structural and financial incentives and constraints in Austria. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research.

England, P., Mishel, E., & Caudillo, M. L. (2016). Increases in sex with same-sex partners and bisexual identity across cohorts of women (but not men). Sociological Science, 3, 951–970.

Flores, A. R. (2019). Social acceptance of LGBT people in 197 Countries, 1981 to 2017. Williams Institute, UCLA. Retrieved December 3, 2021, from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Global-Acceptance-Index-LGBT-Oct-2019.pdf

Floyd, F. J., & Bakeman, R. (2006). Coming-out across the life course: Implications of age and historical context. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(3), 287–296.

Gates, G. (2012). LGBT identity: A demographer’s perspective. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, 45(3), 693–714.

Gato, J., Leal, D., Coimbra, S., & Tasker, F. (2020). Anticipating parenthood among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual young adults without children in Portugal: Predictors and profiles. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1058.

Gato, J., Santos, S., & Fontaine, A. M. (2017). To have or not to have children? That is the question. Factors influencing parental decisions among lesbians and gay men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(3), 310–323.

Geary, R. S., Tanta, C., Erens, B., Clifton, S., Frah, P., Wellings, K., Mitchell, K. R., Datta, J., Gravningen, K., Fuller, E., Johnson, A. M., Sonnenberg, P., & Mercer, C. H. (2018). Sexual identity, attraction and behaviour in Britain: The implications of using difference dimensions of sexual orientation to estimate the size of sexual minority populations and inform public health interventions. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0189607.

Goldberg, A. E., Downing, J. B., & Moyer, A. M. (2012). Why parenthood, and why now? Gay men’s motivations for pursuing parenthood. Family Relations, 61(1), 157–174.

Goode, W. J. (1993). World changes in divorce patterns. Yale University Press.

Goodenow, C., Watson, R. J., Homma, Y., & Saewyc, E. (2016). Sexual orientation trends and disparities in school bullying and violence-related experiences, 1999–2013. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(4), 386–396.

Haavio-Mannila, E. and Kontula, O. (2003). Sexual trends in the Baltic Sea area. (Publications of the Population Research Institute, Series D 41). The Population Research Institute, The Family Federation of Finland.

Harber-Aschan, L., Pupaza, E., & Wilson, B. (2022). The legacy of exile for children of refugees: Inequality and disparity across multiple domains of life. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography, 22, 1–10.

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A., & Sanderson, W. (2008). Are individuals’ desired family sizes stable? Evidence from West-German panel data. European Journal of Population, 24(2), 129–156.

Hu, Y., Xu, Y., & Tornello, O. (2016). Stability of self-reported same-sex and both-sex attraction from adolescence to young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 651–659.

ILGA-Europe. (2020). Rainbow map. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://rainbow-europe.org

Joyner, K., Manning, W., & Bogle, R. (2017). Gender and the stability of same-sex and different-sex relationships among young adults. Demography, 54(6), 2351–2374.

Katus, K., Puur, A., & Sakkeus, L. (2008). Family formation in the Baltic countries: A transformation in the legacy of state socialism. Journal of Baltic Studies, 39(2), 123–156.

Katz-Wise, S. L. (2015). Sexual fluidity in young adult women and men: Associations with sexual orientation and sexual identity development. Psychology and Sexuality, 6(2), 189–208.

Katz-Wise, S. L., Rosario, M., Calzo, J. P., Scherer, E. A., Sarda, V., & Austin, S. B. (2017). Endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones among sexual minority young adults in the Growing Up Today Study. Journal of Sex Research, 54(2), 172–185.

Kolk, M., & Andersson, G. (2020). Two decades of same sex marriage in Sweden: A demographic account of developments in marriage, childbearing, and divorce. Demography, 57(1), 147–169.

Költő, A., Young, H., Burke, L., Moreau, N., Cosma, A., Magnusson, J., Windlin, B., Reis, M., Saewyc, E. M., Godeau, E., & Gabhainn, S. N. (2018). Love and dating patterns for same- and both-gender attracted adolescents in Europe. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(4), 772–778.

Kranz, D., Busch, H., & Niepel, C. (2018). Desires and intentions for fatherhood: A comparison of childless gay and heterosexual men in Germany. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(8), 995–1004.

Kühne, S., Kroh, M., & Richter, D. (2019). Comparing self-reported and partnership-inferred sexual orientation in household surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 35(4), 777–805.

Laumann, E., Gagnon, J., Michael, R., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. University of Chicago Press.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2020). The second demographic transition, 1986–2020: Sub-replacement fertility and rising cohabitation: A global update. Genus, 76(10), 77.

Liefbroer, A. C. (2005). The impact of perceived costs and rewards of childbearing on entry into parenthood: Evidence from a panel survey. European Journal of Population, 21(4), 367–391.

Liefbroer, A. C. (2009). Changes in family size intentions across young adulthood: A life-course perspective. European Journal of Population, 25(4), 363–386.

Lippus, H., Laanpere, M., Part, K., Ringmets, I., Rahu, M., Haldre, K., Allvee, K. & Karro, H. (2015). Eesti naiste tervis 2014: Seksuaal- ja reproduktiivtervis, tervisekäitumine, hoiakud ja tervishoiuteenuste kasutamine [Estonian women’s health 2014: Sexual and reproductive health, health behaviour, attitudes and use of healthcare services]. Tartu Ülikooli naistekliinik.

Liu, H., & Rezcek, R. (2021). Birth cohort trends in health disparities by sexual orientation. Demography, 58(4), 1445–1472.

Manning, W. D., Brown, S. L., & Stykes, J. B. (2016). Same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couple relationship stability. Demography, 53(4), 937–953.

Martinez, K., & McDonald, C. (2021). Childhood familial victimization: An exploration of gender and sexual identity using the scale of negative family interactions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3/4), 1119–1140.

Matysiak, A., Styrc, M., & Vignoli, F. (2014). The educational gradient in marital disruption: A meta-analysis of European research findings. Population Studies, 68(2), 197–215.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Miettinen, A., Gietel-Basten, S., & Rotkirch, A. (2011). Gender equality and fertility intentions revisited: Evidence from Finland. Demographic Research, 24(20), 469–496.

Mishel, E., England, P., Ford, J., & Caudillo, M. L. (2020). Cohort increases in sex with same-sex partners: Do trends vary by gender, race, and class? Gender and Society, 34(2), 178–209.

Moliero, C., & Pinto, N. (2015). Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, contoversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1511.

Möllborn, S., & Everett, B. (2015). Understanding the educational attainment of sexual minority women and men. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 41(1), 40–55.

Ott, M. Q., Corliss, H. L., Wypij, D., Rosario, M., & Austin, S. B. (2011). Stability and change in self-reported sexual orientation identity in young people: Application of mobility metrics. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(3), 519–532.

Perelli-Harris, B., & Gerber, T. P. (2011). Non-marital childbearing in Russia: Second demographic transition or pattern of disadvantage? Demography, 48(1), 317–342.

Perelli-Harris, B., & Lyons-Amos, M. (2016). Partnership patterns in the United States and across Europe: The role of education and country context. Social Forces, 95(1), 251–281.

Perelli-Harris, B., Sigle-Rushton, W., Kreyenfeld, M., Lappegård, T., Keizer, R., & Berghammer, C. (2010). The educational gradient of childbearing within cohabitation in Europe. Population and Development Review, 36(4), 775–801.

Philipov, D., & Bernardi, L. (2011). Concepts and operationalisation of reproductive decisions implementation in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Comparative Population Studies, 36(2/3), 495–530.

Philipov, D., Spéder, Z., & Billari, F. C. (2006). Soon, later, or ever? The impact of anomie and social capital on fertility intentions in Bulgaria (2002) and Hungary (2001). Population Studies, 60(3), 289–308.

Phillips, G., II., Turner, B., Felt, D., Han, Y., Marro, R., & Beach, L. B. (2019). Trends in alcohol use behaviors by sexual identity and behavior among high school students, 2007–2017. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(6), 760–768.

Prince, B. F., Joyner, K., & Manning, W. D. (2020). Sexual minorities, social context, and union formation. Population Research and Policy Review, 39(1), 23–45.

Puur, A., Rahnu, L., Abuladze, L., Sakkeus, L., & Zakharov, S. (2017). Childbearing among first and second-generation Russians in Estonia against the background of the sending and host countries. Demographic Research, 36(41), 1209–1254.

Puur, A., Rahnu, L., Maslauskaitė, A., & Stankūnienė, V. (2016). The transforming educational gradient in marital disruption in Northern Europe: A comparative study based on GGS data. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 47(1), 87–110.

Puur, A., Vseviov, H., & Abuladze, L. (2018). Fertility intentions and views on gender roles: Russian women in Estonia from an origin-destination perspective. Comparative Population Studies, 43(4), 275–306.

Quinlan, R. J. (2003). Father absence, parental care, and female reproductive development. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 24(6), 376–390.

Remafedi, G., Resnick, M., Blum, R., & Harris, L. (1992). Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics, 89(4 Pt 2), 714–721.

Rezcek, C., Spiker, R., Liu, H., & Crosnoe, R. (2016). The promise and perils of population research on same-sex families. Demography, 54(6), 2385–2397.

Rieger, G., Linsenmeier, J. A., Gygax, L., & Bailey, J. M. (2008). Sexual orientation and childhood gender nonconformity: Evidence from home videos. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 46–58.

Riskind, R. G., & Patterson, C. J. (2010). Parenting intentions and desires among childless lesbian, gay, and heterosexual individuals. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(1), 78–81.

Riskind, R. G., & Tornello, C. J. (2017). Sexual orientation and future parenthood in a 2011–2013 nationally representative United States sample. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(6), 796–798.

Riskind, R. G., Patterson, C. J., & Nosek, B. A. (2013). Childless lesbian and gay adults’ self-efficacy about achieving parenthood. Couple and Family Psychology Research and Practice, 2(3), 222–235.

Roberts, A. L., Austin, S. B., Corliss, H. L., Vandermorris, A. K., & Koenen, K. C. (2010). Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2433–2441.

Roberts, A. L., Glymour, M. M., & Koenen, K. C. (2013). Does maltreatment in childhood affect sexual orientation in adulthood? Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 42(2), 161–171.

Roberts, A. L., Rosario, M., Corliss, H. L., Koenen, K. C., & Austin, S. B. (2012). Childhood gender nonconformity: A risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics, 129(3), 410–417.

Rogers, S. M., & Turner, C. F. (1991). Male-male sexual contact in the USA: Findings from five sample surveys, 1970–1990. Journal of Sex Research, 28(4), 491–519.

Ross, H., Gask, K., & Berrington, A. (2011). Civil partnership five years on. Population Trends, 145, 172–202.

Saewyc, E. M., Bauer, G. R., Skay, C. L., Bearinger, L. H., Resnick, M. D., Reis, E., & Murphy, A. (2004). Measuring sexual orientation in adolescent health surveys: Evaluation of eight school-based surveys. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(4), 345.e1-345.e15.

Saewyc, E. M., Skay, C. L., Pettingell, S. L., Reis, E. A., Bearinger, L., Resnick, M., Murphy, A., & Combs, L. (2006). Hazards of stigma: The sexual and physical abuse of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents in the United States and Canada. Child Welfare, 85(2), 195–213.

Savin-Williams, R. C., & Ream, G. L. (2007). Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(3), 385–394.

Savin-Williams, R. C., & Vrangalova, Z. (2013). Mostly heterosexuals as a distinct sexual orientation group: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Developmental Review, 33(1), 58–88.

Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, Y. J., Nathanson, C. A., & Fields, J. M. (1999). Do fertility intentions affect fertility behaviour? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(3), 790–799.

Simon, K. A., Tornello, S. L., Farr, R. H., & Bos, H. M. (2018). Envisioning future parenthood among bisexual, lesbian, and heterosexual women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(2), 253–259.