Abstract

Despite long-term interest in whether welfare benefits motivate fertility, evidence from research has not been consistent. This paper contributes new evidence to this debate by investigating the fertility effect of a German welfare reform. The reform decreased the household income of families on welfare by 18% in the first year after the birth of a baby. Using exclusive access to German social security data on over 460,000 affected women, our analysis finds that the reform leads to a fertility reduction of 6.8%. This result implies that for mothers on welfare, fertility has an income elasticity of 0.38, which is much smaller than that of general populations reported in the literature. Our findings suggest that welfare recipients’ fertility reacts less strongly to financial incentives than the fertility of overall populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Do generous welfare benefits increase the fertility of families on welfare? For decades, this question has been the object of interdisciplinary research. This issue is of considerable interest to policy makers because a strong fertility reaction to changes in welfare benefits may provide support for advocates of cuts in welfare spending. The most prominent example of policy motivated by this line of thought is Family Caps in the US. These policies reduced welfare benefits when children were born to families while the mother received welfare.Footnote 1

The idea that welfare benefits enhance fertility aligns with dominant theory on family economics. Becker’s (1960) seminal works suggest that fertility is negatively correlated with the price for children. Child-related welfare benefits reduce the price for children and should therefore increase fertility. Many studies show a positive correlation between child-related benefits and fertility, but thus far, only in regard to child benefits paid indiscriminately to entire populations.Footnote 2 The fertility reaction of welfare recipients might differ from that of general populations for several reasons.

On the one hand, the fertility reaction of welfare recipients might be stronger because for them, child-related benefits present large amounts relative to the rest of their income. On the other hand, welfare recipients might react less strongly because an additional child may decrease the probability of exiting the welfare system, which may be a desire of many welfare recipients. Therefore, families’ on welfare might be less sensitive to short-term financial incentives. Additionally, welfare recipients may be less sensitive to short-term changes in benefits as they expect more long-term financial hardship in caring for their children than non-welfare families. Despite the relevance of the question and the theoretical ambiguity of the answer, research has not yet found convincing evidence to resolve it. The challenge is that fertility research requires large data sets and data sources containing fertility information for large numbers of welfare recipients are sparse.Footnote 3

In this paper, we have exclusive access to an exceptional administrative data set on welfare recipients that contains fertility information about all families on welfare in Germany. The data are precise to one day and contain information on all births in families on welfare for a 12-year period. In addition, the data include information about maternal education, age, nationality, and some additional sociodemographic characteristics.

We use these data to estimate the fertility reaction of families receiving welfare to a very sudden and surprising German reform that effectively reduced the net household income of parents receiving welfare by 18% on average in the first year after the birth of a child. The reform, which came into effect on January, 1st 2011, changed the status of parental leave benefits (PLB) which are paid for 14 months after birth of a child for all families receiving welfare benefits. Before the reform, families on welfare with a young child received 300 Euros PLB in addition to their regular welfare benefits. After the reform date, the 300 Euros PLB were fully deductible from the regular welfare benefits. Therefore, after the reform date the available income of families on welfare decreased by 4,200 Euro (approximately 5,000 US-$) during the first 14 months after the birth of a child in comparison to families who gave birth 14 months earlier.

To identify the reform effect, we use the unexpected introduction of the reform and analyze whether it caused a structural break in the probability that highly affected mothers receiving welfare benefits will give birth.Footnote 4 We find a fertility reduction of 6.8% as an immediate response to the welfare reduction, indicating an income elasticity of fertility of 0.38,Footnote 5 which is much smaller than what the literature finds for the reactions of overall populations to changes in general child benefits (see Table 1). We also find that the reform had a long-term impact, as the fertility rate remained at a lower level for at least 5 years after the reform. Furthermore, women who could not defer their fertility, those aged 38–45, reacted in a similar order of magnitude as the rest of the sample. In addition, we find that the spacing and timing of births did not increase. Both findings support the conclusion that the reform had an impact on completed fertility. These results are robust to changes in the functional form of the estimation model, sample definitions, and placebo estimations.

This study contributes more robust evidence to the literature on the fertility effect of welfare benefits than previous research for two reasons. First, the sudden 18% reduction in household income is larger than the monetary impact of reforms investigated in the previous literature.Footnote 6 Such a large reduction is unlikely to be compensated by savings, transfers from relatives, or other sources. Therefore, we are certain that the reform reduced the available income by a substantial amount.

Second, we use administrative data obtained from the German Federal Employment Agency to analyze the fertility of welfare recipients. This data source contains detailed information on approximately 463,000 directly affected women and includes a panel of monthly observations over a 12-year period. Previous studies using microlevel data to analyze the nexus of welfare and fertility all used less than 10,000 units of observation. These small samples are problematic since childbirth is a relatively rare event in the life of an individual woman. Only large samples contain enough variation in the dichotomous variable “birth” or “no birth” to robustly identify effects. Therefore, the availability of data on an exceptionally large welfare reduction coupled with the large sample obtained using administrative data provided an excellent opportunity for this study to reveal the fertility effect of welfare benefits.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section "Literature review" summarizes the previous literature. Section "Institutions" describes the relevant institutions. Section "Data" describes the data. Section "Empirical strategy and threats to identification" presents the estimation strategy. Section "Results" presents the main estimation results. Section "Robustness" presents the robustness checks. Section "Discussion and conclusion" discusses the results and presents the conclusions.

Literature Review

Until the 1990s, the literature on the impact of child-related welfare benefits on fertility focused on the US welfare system. In his comprehensive literature review, Moffitt (1998) concludes that the evidence points toward a mild positive effect of increased child-related welfare benefits on fertility. The range of the point estimates for the effect varies greatly among studies. All results are highly sensitive to the methodology and the estimation sample of the respective studies. Additionally, the results of studies that consider variations among different states in the US and over time are affected by intracluster correlation, which are not adjusted for (Bertrand et al., 2004).

The most recent literature about child-related welfare benefits and fertility in the US analyzes the effect of the introduction of family caps in 23 states (e.g., Argys et al., 2000; Camasso et al., 1999; Dyer & Fairlie, 2004; Jagannathan et al., 2004; Joyce et al., 2004; Kearney, 2004; Wallace, 2009). These policies reduce or deny welfare benefits for additional children who are born while a woman receives welfare benefits. Two states, Arkansas and New Jersey, monitored the introduction of their Family Cap policies with randomized controlled trials. A number of studies analyze these trials, most notably Turturro et al. (1997) and Camasso et al. (1999). These studies find a fertility reduction for newly welfare-dependent women. However, as Loury (2000) points out, the results of these studies are difficult to interpret because multiple problems are apparent in the experimental design, such as selective attrition and selective assignment to treatment (Kearney, 2004). The most recent publications on family caps by Kearney (2004) and Wallace (2009) rely on survey data obtained from a small number of potentially affected women. These studies use variations in the introduction of family caps across states and over time to identify the fertility effect of family caps. Like most earlier studies, neither of these studies finds a significant effect.Footnote 7

Apart from studies on the US, the only studies about the nexus between welfare benefits and the fertility of welfare and low-income families come from the UK. In 1999, the UK government enacted the Working Families’ Tax Credit, which aimed to encourage low-income families with children to obtain employment, leading to an increase in support for children in low-income families by up to 50%. Thus far, two studies have examined the fertility effect of these reforms. Francesconi and van der Klaauw (2007) find no significant effect on the fertility of lone mothers. Brewer et al. (2012) find an increase in fertility of approximately 15% for women in couples. However, as these studies investigate a welfare to work program, the effects they identify are confounded by the fertility effect of the work incentives this program provides.

While research on the effect of welfare on fertility is inconclusive, the literature about general child-related benefits and their effect on fertility agrees that these transfers have a sizable positive effect on birth rates. Milligan (2005) examines the effect of a universal child benefit that was introduced in Quebec in 1988. He finds a significant positive effect using a difference-in-differences strategy that employs the rest of Canada as a control group. Cohen et al. (2013) consider variations over time and birth parity in the amount of child benefits for marginal children in Israel. They find a decrease in fertility of 9.6% as a reaction to a decrease in child benefits of approximately $34 a month.Footnote 8

González (2013) and González and Trommlerová (2020) analyze the fertility effect of the introduction and cancelation of a one-time payment of 2500 Euros to the parents of newborn children in Spain. These articles find an increase in birth rates between 3 and 6% as a reaction to the policy due to a decrease in abortions and an increase in conceptions. The announcement to cancel the policy led to a transitory increase in birth rates of 4% just before the cancelation was implemented. This increase was driven by a short-term drop in abortions. The cancelation then led to a 6% drop in the birth rate. Azmat and González (2010) also find a 5% increase in fertility by a reform in the Spanish income tax. In contrast, Tudor (2020) focuses on Romania, finding that a substantial increase in maternity leave benefits led to a 4% increase in monthly live births. This increase in live births is due to a significant decrease in the probability of abortion, whereas there is no change in the conception rate. However, Tudor (2020) does not quantify the size of the maternity leave benefits increase, which means we cannot calculate the income elasticity of fertility.

Riphahn and Wiynck (2017) examine the effect of an increase in child benefits in Germany and find no effect on first births and an increase in fertility between 9.6% and 22.6% for the second births of high-income parents. Cygan-Rehm (2016) and Raute (2018) look at the introduction of PLB in Germany, which increased the cost of children for low-income families and decreased them for high-income families. Cygan-Rehm (2016) finds an effect of consistently lower birth rates for 5 years for low-income women with a previous birth. Raute estimates a fertility effect of 2.1% per 1,000 Euro change in the benefit. As Cygan-Rehm (2016) examines the fertility of low-income mothers in Germany, her paper is close to our paper. However, she investigates a reform that just affected previously employed mothers who are likely to have different income elasticities of fertility than welfare receiving women.

Institutions

This study analyzes a reform that affects the interaction between welfare benefits and PLB. The following chapter gives an overview of the features of these benefits that are relevant for the analysis and of the reform that altered this interaction.

Parental Leave Benefits

PLB are state transfers to the parents of young children. They are designed as a substitute for the forgone earnings of parents who take parental leave to care for their child. Parents of children up to the age of 14 months are eligible if they reduce or stop working. Each parent can receive PLB for at most 12 months. The combined number of months for both parents cannot exceed 14 months. The parents can receive PLB at separate times or jointly. Single parents can receive PLB for 14 months. The amount of PLB is calculated as approximately 67% of the respective parent’s average net labor earnings in the 12 months before the child’s birth. There are upper and lower bounds for the amount of PLB parents can receive. Eligible parents who did not work before the child’s birth or had net labor earnings of less than 300€ received 300€ a month. Parents who earned more than 2.769€ receive 1.800€ a month (BEEG, 2010).

Welfare Benefits in Germany

The basic welfare benefits for unemployed and marginally employed individuals in Germany are called unemployment benefits II. This program is the only available welfare support for employable adults in Germany and take up is almost complete. In the following, we refer to these benefits as welfare and we call households “on welfare” whenever they receive welfare payments. For households without any employable adults, such as people with disabilities and retirees, other rules apply, but the payment amounts are the same.

Eligibility and the amount of welfare are determined at the household level.Footnote 9 A household can be one person or more. All households are eligible to receive welfare under two conditions. First, the adult household members’ wealth is below an age-dependent threshold, approximately 10,000 Euros per employable adult (SGB II §12, 2003). Second, their monthly income (other than welfare) has to be very low or nonexistent. The income has to be below a certain threshold—welfare entitlement. The welfare entitlement is the amount of welfare the household would receive if it had no other income at all. Thus, welfare entitlement is the lowest income level a person can have in Germany. Whoever has less income from other sources, gets welfare payments on top to reach at least the income level of the welfare entitlement. (BMAS, 2018; SGB II §7, 2003).

In the determination of eligibility and the amount of welfare paid, it does not matter which household member generates other sources of income. The combined net income of all household members is what matters. The principle of the welfare system is that if there are household members who earn enough to support the others, they are obliged to do so. Only if the combined income of the household is lower than the welfare entitlement will the state top up the income.

Three factors (standard rate, rent, and additional needs) determine the amount of welfare entitlement. First, the standard rate differs by household member and is designed by legislature to represent the minimum consumer expenditures for basic necessities such as food, clothes, and transportation required for social existence (SGB II §20, 2003). Table A.1 in Online Appendix A lists the standard rates by household member for 2010 and 2011. The second factor, rent, includes heating costs. However, only rent in the lower range of the local price level is covered. The last factor, additional needs, allows for special circumstances. The most relevant of these circumstances are single parenthood and pregnancy.Footnote 10

The amount of welfare to be paid out to a household is determined by deducting other sources of household income from the entitlement. Capital income, most labor income and most state transfers—such as child benefits, which are no welfare payments as all families in Germany are eligible for such transfers—are fully deducted. The only exempted state transfers used to be PLB. The 2011 reform ended this exemption.

Table 2 shows two examples of how welfare entitlements are calculated, how other sources of income are deducted, the amount of welfare paid out to families, and the total amount that families have at the end of each month. We show these calculations for two different hypothetical families who received PLB in either December 2010 or January 2011. The first family consists of a single mother who does not work and has two children, and the second example is a couple with three children, where the father has net earnings of 1000€ a month.

Showing these examples at two different points in time emphasizes that while there were other small changes in the welfare system between December 2010 and January 2011, the deduction of PLB by far had the largest impact on families with young children. Before the reform households on welfare received 300 Euro PLB per month on top of their welfare entitlement, and after the reform, the 300 Euro PLB were deductible income. The impacts of a 5 Euro increase in the standard rate for adults and a slight decrease in the deduction of labor income are negligible in comparison to the impact of the reduction caused by the reform.

The Reform

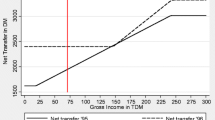

On June 7, 2010, the German government announced austerity measures as a consequence of the financial and Euro crises. One of the measures changed the status of the 300€ minimum PLB provided to welfare recipients (Bundesregierung 2010). The reform took effect on January 1st, 2011. Before this date, the 300€ PLB were paid out on top of welfare payments regardless of whether the parent worked before childbirth. After January 1st, 2011, these PLB were fully deducted from welfare if the parent who received PLB did not work before the birth of the child. This reform led to a cut in benefit receipt of up to 4,200€ (14 months times 300€) in comparison to welfare families who had their child early enough that the reform did not affect them and received PLB for 14 months. Figure 1 illustrates how the reform affects the household income of a welfare receiving single mother with two children depending on the birth month of the second child.

Yearly disposable household income depending on child’s birth month. The graph shows the yearly disposable household income for a welfare receiving single mother with two children depending on the birth month of the second child. The disposable income corresponds to the figures in table two, minus the cost of accommodation. The yearly refers to the first year of the second child’s life. The graph depicts the case of a mother who is fully welfare dependent aside from PLB. This means she receives 300 Euros of PLB for 14 months. Depending on the birth month of her child, these 300 Euros are deducted from her welfare payments for a part of these 14 months. The first red line marks November 2009. If a child is born before this month, the household’s income is not affected by the reform. Since the figure shows the yearly income, the negative slope only starts from birth month January 2010 (second red line), because before this birth month, the household income only gets affected after the first year of the child’s life is already over. The third red line marks January 2011, the calendar month when the parental leave benefits were first deducted from welfare. If a child is born in this month or later, the mother does not benefit at all from PLB and loses the 300 Euros a month for the entire 14 months.

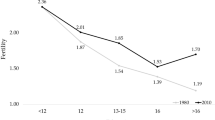

If a parent did work before the child’s birth, the PLB is not fully deducted from the welfare benefits. The amount of the PLB that corresponds to the average net earnings in the 12 months before the birth is exempt from deduction as long as it does not exceed 300€ (BEEG, 2010). This new calculation means that if, e.g., a mother earned an average of 200€ per month in the year before giving birth, she would receive 300€ in PLB and 100€ would be deducted from the welfare benefits. If a mother earned an average of 400€ per month, then she would receive 388€ in PLB, and everything exceeding 300€–88€—would be deducted from her welfare benefits. Figure 2 illustrates how earnings in the year before child birth affect household income during the first year of the child’s life.

Yearly disposable household income depending on parent’s past labor income. The graph looks at the situation for the same family from Fig. 1.1 for the case that the child is born in January 2011 or later. Thus, the household income would be affected by the reform during the entire time the mother receives PLB. What is different for the family in this figure, is that the mother worked before child birth. The more she earned in the 12 months before the child’s birth, the less of her PLB money is deducted from the welfare payments and the higher is the household income during the first year of the child’s life. The average of the mother’s monthly earnings during the 12 months before the child’s birth is not deducted, and this counts for each month she receives PLB. Effectively this means for the yearly household income in the first year of the child’s life, that for every Euro the mother earned the year before birth, she receives an additional Euro after birth. This is true until the threshold of 3,600€ labor income, which is marked by the red line in the figure. Any earnings above that are irrelevant for household income during the PLB period. They would increase PLB above 300€ a month, but every Euro exceeding 300€ would be deducted from welfare again.

The government decided to implement the reform during a weekend cabinet retreat that occurred on June 6, 2010, and announced it on June 7 (Bundesregierung 2010). It is highly unlikely that anyone anticipated the reform before this time because it was part of a package of austerity measures introduced in the wake of the economic crisis. The government coalition of Christian Democrats (CDU) and Liberal Democrats (FDP) had a stable majority in parliament; therefore, the fact that the cabinet decision would become legislation was not contested. Accordingly, all media coverage indicated that there was no question about whether the reform would be implemented (Spieker, 2010; SZ, 2010). The government was so certain about passing this reform that it ordered the unemployment agency to send letters to welfare recipients informing them about the reduction before the reform was even passed in parliament (NTV, 2010).

The austerity package that was affirmed on June 6 was the lead topic in all TV news and newspapers on June 7, with many media especially and explicitly discussing the PLB deduction for welfare recipients because it was the most controversial news item (Nitsche, 2010). The massive media coverage on the reform that occurred after the cabinet meeting implies that affected families would have learned about this reform in early June 2010. While not everyone might have directly seen the news, it is plausible to assume that welfare recipients, especially those who planned to have a child or were already pregnant, would have heard about the reform.

Before June 2010, there was no indication that the interaction between welfare benefits and PLB would be affected by the austerity measures. The government explicitly stated that the reform was implemented due to austerity concerns. There were no statements by the government or the media that indicated the reform had been intended to influence fertility or welfare recipients’ work incentives. Therefore, anticipation effects leading to an adjustment in fertility behavior or the labor supply before June 2010 are not plausible.

Data

This analysis draws from exclusive access to very accurately tracked administrative data from the Federal Employment Agency of Germany.Footnote 11 These data provide information about household composition, and labor market- and fertility histories for all welfare receiving households in Germany. Fertility can be tracked, because the data contain the birthdates of all household members. The data cover specific timespans that are accurate to one day, and a new observation is generated every time the value of any of the stored variables for a person changes. Between January 2005 and April 2017, 7.4 million women in the fertile age range—between 18 and 45 years old—lived in the observed households.

We use a 50% random sample of women in these households to create a panel of monthly observations between January 2005 and December 2016 for every woman in the dataFootnote 12 born between 1959 and 1998. The women stay in the sample as long as they are between 18 and 45 years old. Therefore, the panel is not balanced as women enter and leave the panel by aging. Overall, the panel contains almost 400 million observations.

To compile our estimation sample, we apply three further sample restrictions to the data. The estimation sample contains only women who, first, received welfare in January 2010 or earlier—1 year before the reform—, second, either continued to receive welfare or received it again in December 2016 or later, and third, had at least one child before January 2010. We impose restriction (1)—women who received welfare for the first time in January 2010 or earlier—because we expect women who received welfare for the first time after the reform was announced to react weaker or not at all to the reform. Since the reform affects women only while they receive welfare, these women’s fertility incentives would not abruptly change due to the introduction of the reform but rather at the time they first started receiving welfare, and thus, this change cannot be captured with our estimation approach. We choose January 2010 as the relevant month because it is far enough before the announcement of the reform, making it unlikely that the reform itself affects whether or not a family is part of the sample. We show in section "Robustness", Table 7, Panel A that the results are not affected by the point in time chosen for this restriction.

We impose restriction (2)—to include only women who received welfare in December 2016 or later—because of the way the source data are structured. We infer women’s fertility histories from the birth dates of their children. For each month a woman receives welfare, we see the birth dates of all members of her household. From the moment a woman leaves welfare receipt for the last time, we cannot see if she has further children. This means our dependent variable—birth in month t, yes/no—is missing after this point in time. If we kept all women’s observations up to the time they receive welfare for the last time, we would introduce selective attrition correlated to the reform. The suspected reform effect is a reduction in fertility and having another child increases the chances to remain dependent on welfare benefits. For the main sample, we choose December 2016 as the inclusion date. In the robustness checks we test the effect of shifting the inclusion date. The results are described in section "Robustness", Table 7, Panel B. The test shows that the year we choose for this restriction does not change the results.

Finally, we impose restriction (3)—women who had at least one child before January 2010—because the birth of the first child, rather than subsequent births, is often the initial reason for receiving welfare. This renders the strategy of conditioning on welfare receipt before a certain month infeasible for first births, therefore, we cannot estimate the precise effect of the reform on first births. Online Appendix B explains the problem in further detail and presents suggestive results of the reform on first births.

Applying the restrictions reduces the 3.7 million women from the 50% sample, to a final sample of 463,000 women, for whom the data set contains approximately 46 million monthly observations. Between 2005 and 2016, these women gave birth to 285,000 children, which constitutes an average annual birth rate of 7.4%. Some of the women contribute more than one birth to this number. The women who are captured through the three restrictions are a highly welfare dependent portion of the larger sample.. Many of the women in the unrestricted sample received welfare for only short periods. On average, the 3.2 million women who are excluded because of the restrictions, received welfare for 31% of the time we observe them.Footnote 13 Table 3 gives an overview of the observed births by parity and women’s characteristics: number of children at their first and last observation, education level,Footnote 14 marital status and cohort. Table A.2 summarizes women’s tertiary degrees, their world region of origin and in which federal state they live.

Empirical Strategy and Threats to Identification

Empirical Strategy

The reform that deducts PLB from welfare benefits provides a natural quasi-experiment in which the reform’s fertility effect can be identified with a linear probability model. We assume that there will be a sudden and sizeable drop in the sample’s birth rate because the reform was completely unanticipated before its announcement and implemented only 6 months later and the reduction in relative household income is exceptionally large and directly tied to fertility. To estimate the magnitude of the fertility reduction, we estimate the following model:

where birth is a dummy variable indicating that woman i gave birth to a child in month t. \(post\) is a treatment indicator that is set to 0 before the reform could have had an effect on the birth rate—from January 2005 to December 2010—and 1 afterward—starting in April 2011. The model looks very similar to a regression discontinuity design (RDD). It is not a classical RDD model, however, because the units of observation on both sides of the cutoff are the same. In an RDD model the cutoff divides the sample into treatment and control groups. Thus, it is a “pre-post-difference” model, using only the first difference from a difference-in-difference (DiD) model. We would have liked to apply DiD as a more robust identification strategy. Unfortunately, we were not able to find a valid control group for our sample. Despite an intensive search we could not find a relevant group with parallel pre-reform fertility trends.

We exclude observations from January 2011 to March 2011 in the baseline specification, as in these months the welfare reduction can only influence the birth rate via changes in abortions.Footnote 15 FromFootnote 16 April 2011 onward, we can observe the full effect of the reform, which is impacted not only by more abortions but also by an increased use of contraceptives or higher abstinence. m is a trend variable that is included in the baseline specification in both linear and quadratic form and interacted with the post-dummy. month is a set of 11 month-of-year dummies that control for seasonality. X is a vector of control variables including dummies for the mother’s age in four-year steps, her nationality and the federal state of residence. The main coefficient of interest from this regression is \(\beta\), the coefficient of the post-reform dummy.

Threats to Identification

The greatest threat to the identification of the true fertility effect in our analysis is sample selection. The reform reduced welfare benefits for the parents of young children. Parents who did not receive welfare when their child was younger than 15 months were not affected by the reform. Therefore, women and couples who planned to have a child had an incentive to postpone fertility until they entered a period when they did not receive welfare benefits. Such fertility postponement would avoid the income reduction caused by the reform. Our data provide fertility information about a woman only until the last month she received welfare. Hence, sample selection may influence our results—women may have deferred fertility as a reaction to the reform. Women who chose not to have another child would stop receiving welfare benefits earlier, and thus, the probability of leaving the sample would increase.

In the results section, we test for the influence of sample selection by estimating the main equation using subsamples divided by education and the number of previous children. If sample selection is the driver of the structural break, we should find weaker or no structural breaks for groups at high risk of continuously receiving welfare benefits because it is harder for them to find a job and become independent of welfare payments. However, the estimated fertility effect for groups at high risk of receiving welfare is larger than the estimated effect for the groups who could find a job more easily (see Tables 4 and 5 described in detail below).

Another potential threat to identification is that contemporaneous reforms might have influenced or caused the effect we identify. There are no law changes in 2010 and 2011, which are likely to generate significant bias, as no other reforms influenced fertility at the time in question. Figure 3 compares the seasonality-adjusted monthly birth rate in Germany to that of the main sample.Footnote 17 The figure shows that before the reform, the birth rate of our sample remains continuously higher without a clear upward or downward trend over time. Then, a break occurs around the time of the reform. The general German birth rate trends upward without any extraordinary changes around 2010 or 2011. Therefore, if any other policy change caused the effect we find, it would have been a change that specifically affected the sample group of welfare recipients. There were no such changes in the relevant period.

Comparison of birth rates: sample vs. overall German population. Please note that the monthly birth rate of the sample is age adjusted. Since the sample ages over time, the unadjusted birth rate has a strong negative trend at all times before and after the reform. The German birth rate shown here is not age adjusted because we do not have adequate data for the age adjustment. Overall, the average age of German 18- to 45-year-old women is increasing with time. Thus, an age adjustment would lead to a steeper increase in the birth rate over time. The birth rates of the sample and the German population are seasonally adjusted. The German birth rate contains first births, because we have no data about parity specific birth rates for Germany as a whole. The first red vertical line marks January 2011, the first month in which the reform announcement could affect the birth rate due to abortions. The second red vertical line marks April 2011, the first month in which the reform announcement could affect the birth rate due to increased use of contraceptives, higher abstinence, or more abortions.

Results

This section presents the results of estimating Eq. 1 for the full main sample followed by estimates for subsamples separated by parity and by the women’s level of secondary education. Showing the results for different subsamples reveals the degree of heterogeneity in the reform effect. Furthermore, the use of these subsamples allows for conclusions to be drawn about the degree to which selection out of the sample drives the effect because the displayed groups differ greatly in terms of their probability of receiving welfare on a continuous basis. If the groups who receive welfare most persistently react as strongly to the reform as those who are likely to stop receiving welfare benefits, this corroborates that the effect we identify is driven by an actual reduction in fertility rather than sample selection.

Figure 4 is closely related to the main sample’s birth rate plot in Fig. 3. It shows a residual plot of the monthly birth rate of the full main sample. The residuals are obtained from a regression that controls for the month of the year and the women’s age, nationality and federal state. The dependent variable is depicted as a residual plot rather than showing raw data because monthly birth rates have considerable seasonal variations, and the aging of our sample over time introduces a trend, which obscures the reform effect if we do not control for age. Furthermore, the residuals are rescaled to represent a relative deviation from the average birth rate in 2010 because the residuals are miniscule numbers that are not intuitively interpretable.Footnote 18

Birth rate residuals relative to the birth rate in 2010. The residuals are obtained from a linear probability model in which the birth dummy variable is regressed on age, federal state, month of year and world region of origin. The sample is the main estimation sample, meaning women who have at least one child and received welfare before January 2010 and after December 2016. The blue line shows the mean of residuals for each month. These means are rescaled to represent how far they deviate from the birth rate for 2010, which was 7.6% in yearly terms and 0.63% in monthly terms. The first red vertical line marks January 2011, the first month in which the reform announcement could affect the birth rate due to abortions. The second red vertical line marks April 2011, the first month in which the reform announcement could affect the birth rate also through increased use of contraceptives and higher abstinence. The black dashed line shows the quadratic trend prediction as calculated by Eq. 1.

In 2010, the 349,607 women in the sample at that time gave birth to 25,612 babies, which constitutes an annual birth rate of 7.6%. The dashed line shows the quadratic pre- and post-reform trends as calculated by Eq. 1. The vertical red lines mark January 2011, the month that the announcement of the reform could first affect the birth rate via an increased abortion rate, and April 2011, the month increased contraceptive measures could take full effect.

The graph shows that the birth rate dropped sharply in January 2011, followed by a further rapid decline until June 2011. While the birth rate varies substantially from month to month before the reform, the drop in 2011 leads to the lowest birth rate since the beginning of the observation period and remains at a lower level despite an upward trend. This pattern is suggestive evidence that the reform permanently lowered fertility. The residual plot starts dropping in January 2011. This early drop could either be coincidental, as it lies within the usual range of variation seen prior to the reform, or it might be influenced by an increase in abortions starting in June 2010.

We split the main sample by birth parity and education. Figure A.1 in Online Appendix A shows the residual plots for the subsamples, and all of these plots confirm the pattern displayed in Fig. 3. Table 4 shows the results for estimating Eq. 1 first for the full sample, then by birth parity and education. As in all estimation tables that follow, the dependent variable is rescaled by dividing it by the average monthly birth rate for 2010. This procedure simplifies the interpretation of the reform dummy coefficient, as it now directly represents the relative percentage change in the birth rate as a reaction to the reform.

Column 1 shows the estimate for the full main sample. These results demonstrate a drop in the birth rate by 6.76% as a reaction to the reform. Columns 2 and 3 show the results separated by birth parity. The sample in Column 2 contains all mothers that have one child, and the sample in Column 3 contains all mothers with two or more children. The birth rate for mothers with one previous child, and thus the birth rate for second children, dropped by 4.91% compared to the 2010 level. The birth rate for third- and higher-order children dropped by 8.69%. The greater responsiveness of higher-order birth fertility is in line with evidence presented in previous research. While research finds first birth fertility to be highly malleable by interventionsFootnote 19 (Gauthier, 2007), second birth fertility is found to be relatively unresponsive, while higher-order births respond more strongly again (Brewer et al., 2012; Laroque & Salanié, 2014; Milligan, 2005). This difference in responsiveness could be due to the preference of women with one child to have a sibling for their child (Berrington, 2004). How strongly our findings support the hypothesis of higher responsiveness of higher-order births is debatable, though, as the percentage point drop is very similar for second births and higher-order births (0.59 p.p. vs. 0.57 p.p.).

Columns 4 to 7 show the results for women with different levels of secondary education. By far the largest effect is the one for women without a secondary school degree (Column 4). With a reduction in the birth rate of 12.99%, the reaction of these women is approximately twice as strong as the reaction for the main sample and the coefficient has a small standard error. Women without a secondary school degree have the highest fertility of all educational groups. Hence the biggest drop in absolute terms takes place in the group that has the highest fertility. The point estimates for the other educational subgroups are all roughly on the same order of magnitude, with a reduction of 5 to 7%.

Overall, the results of Table 4 show that the reform effect is largest for women with more than one previous child and those with low levels of education. The women in these groups receive welfare most persistently. To show this we created Figure A.2. For this figure, we created a sample of women who fulfill restriction (1) and (3), but not necessarily restriction (2)—it does not matter at what time a woman received welfare for the last time, for her to be part of this sample. Figure A.2 shows the rate of welfare receipt among this sample over time. For the upper panel the women are split up by number of children. It shows how women with two or more children are consistently more likely to receive welfare benefits than women with only one child. The lower panel of Figure A.2 shows the same pattern for the same sample split by education. The lower a woman’s secondary school degree is, the more persistently she receives welfare.

This result is not surprising, as it is increasingly difficult for women to find a job the more children they have and the lower their educational degree is. Furthermore, households with more children receive higher welfare entitlement amounts, and therefore, a larger expansion of labor supply would be required for these individuals to become independent of welfare benefits. If the reform effect we find was driven by sample selection in the form that women who plan to have a child wait until they can leave welfare receipt, we would find a bigger fertility effect for those groups that can leave welfare receipt most easily. The opposite is the case. From this we conclude that the reform effect we find is mostly driven by an actual reduction in fertility rather than by sample selection.

Robustness

Table 5 Panel A shows the results of several robustness tests. Columns 1 to 5 report the results for estimating Eq. 1 using different functional forms, including different polynomials of the trend variables and excluding the separate post-trend variables. Column 6 includes the months January to March in the estimation as post-reform observations. Column 7 shows the results for estimating Eq. 1 without the control variables, and Column 8 includes individual fixed effects. Most of the changes have only a minimal effect on the estimated effect size or its statistical significance. The only exception is adding a quartic trend, which leads to an estimate of 15.8%. With four polynomial terms of the post- and the pre-trend variables, the likely explanation for this deviation is that this model is overfitted.

Column 9 of Table 5 Panel A shows the result for the subsample of all women who never lived in a household with an aggregated labor income of more than 300€ a month. We test this specification because it is possible that families with a low labor income who also received welfare cross the threshold for receiving welfare after January 1st, 2011. Crossing the threshold happens because PLB are deducted from welfare benefits and are therefore treated similarly to labor income. These families would no longer qualify for welfare benefits, possibly permanently, the month after childbirth. This threshold crossing, if it existed, would remove these families from the analysis sample. If this sample reduction caused our effects on fertility, then we would not expect an effect for women from households who never earned income, since those families would definitely not surpass the income barrier because of the reform. As the reform dummy for this subsample is even more negative and graphical evidence (Figure A.3) supports this finding, this mechanic halt in welfare benefits cannot explain the reform effect.

Table 6 reports the results for a placebo test, which estimates the reform effect with reform dummies set at different points in time from 2 years before the actual reform until two years after it in steps of six months. The coefficient for the actual reform (Column 5) has by far the largest absolute value and a small standard error. Most of the coefficients for the placebo dummies are small and have very large standard errors. Only the coefficient for the dummy in July 2011 is highly statistically significant, and the point estimate is approximately half as large as that of the actual reform. The reform dummy in July 2011 is strictly speaking not a placebo test, because it is only statistically significant, because it captures part of the actual reform effect. Since it is the actual reform which drives this result, it does not threaten the validity of the main results.

Table 7 Panel A shows how the results change, if we alter restriction (1)—when a woman received welfare for the first time. In the baseline specification, women had to receive welfare in January 2010 or earlier to be part of the sample. In Column 1, this condition is shifted to January 2005; in Column 2, it is shifted to January 2006, and so on for each year until 2010 (Column 6, baseline). The point estimate remains extremely stable across these shifts. The standard error decreases as the sample size increases. The increase in sample size occurs due to increasingly loosening the condition by shifting the relevant month forward in time. Figure A.4 in Online Appendix A shows that the course of the birth rate residuals is very similar for the different samples, indicating that the results are not driven by women who entered the sample at a particular time.

Table 7 Panel B shows the results for shifting sample restriction (2)—when a woman received welfare for the last time. This approach tests the influence of the year we choose for this condition on the estimate of the reform effect. In the baseline specification, we choose December 2016. Column 1 shows the results for shifting this condition to December 2011; Column 2 shows the results for shifting to December 2012, and so on. The point estimate is negative and highly statistically significant over all specifications but varies between reductions of 4.47% and 9.46% with the baseline estimate, and 6.76% roughly represents the median. Figure A.5 in Online Appendix A shows the residual plots for the samples with the different restrictions. The course of the residual plot and therefore the birth rate over time remain very similar across the different samples.

Table 8 Panel A reports the results of a bandwidth test. Column 1 is the result for a bandwidth of 2 years, 1 year before and 1 year after the reform; Column 2 for a bandwidth of 4 years, 2 years before and 2 years after the reform, and so on until the whole observation period is included in Column 6.Footnote 20 All estimates of the reform dummy in the bandwidth tests are statistically highly significant and negative and have a size comparable to that of the baseline.

Table 8 Panel B shows the estimates for the main sample split by age groups.Footnote 21 We bundle the age groups 18 to 21 and 22 to 25 because separately, they are too small for statistically significant estimations, and the residual plots move too erratically. The two groups have few observations because the precondition to be in the sample is having at least one child, which is less common among young women. Similarly, the age groups 38 to 41 and 42 to 45 are grouped together because births are such a rare event for them that outlier months render their separated residual plots difficult to interpret. Again, all estimates are negative, statistically significant and of a similar order of magnitude. The estimates become less precise with age, though, as births become increasingly rare. The graphical evidence displayed in Figure A.6 in Online Appendix A supports the finding that the reform effect occurs for all age groups. Additionally, women aged 38 to 45 and therefore unable to postpone fertility, show a reduced fertility rate. This evidence shows that the reform also affected completed fertility. We further investigate this assumption in Online Appendix C, which tests whether the reform increased the age at which women had children (timing) or the spacing between children (spacing). An increase in timing or spacing could indicate that the reduction in fertility is caused by postponement rather than a permanent reduction in fertility. Online Appendix C finds suggestive evidence against postponement and for a reduction in fertility.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study investigates the fertility effect of a reform of the German welfare system that made parental leave benefits deductible from welfare benefits. The reform reduced the household income of affected welfare recipients by 18% on average. We find that the reform reduced fertility by 6.8% for women with at least one child who received welfare payments before and after the reform. The availability of large administrative data sets providing detailed information about welfare recipients coupled with a large reduction in relative income directly related to marginal fertility supported an analysis of the effect of welfare on fertility. We obtain robust evidence from regressions and graphical evidence confirming that welfare recipients’ fertility decisions are influenced by financial incentives.

The course of the fertility reaction—a sudden drop at almost the first possible moment, with a slight recovery afterward—suggests that women on welfare were relatively well informed about the reform. Otherwise, the drop would have come later and more gradually. Furthermore, graphical evidence suggests that the reform influenced fertility in the short and long run. The birth rate remains at a decreased level for years after the reform. The consistent decrease in the sample’s birth rate suggests that the negative effect also influences women’s completed fertility. It is plausible to assume that the reform is part of the reason for the continuous decrease in fertility in the sample, but we cannot say to what degree because we have no credible way of gauging the birth rate for a scenario in which the reform did not take place.

Separate analyses of birth timing and spacing show that women who had children after the reform were not significantly older and did not wait longer between births because of the reform. We estimate the reform effect for separate age groups and find that it is similar for women of all ages within the fertile age range. These findings are further suggestive evidence of a negative effect on the completed fertility of the affected women.

Generally, this analysis supports those previous contributions to the literature on the nexus of welfare and fertility that find a positive effect (e.g. Brewer et al., 2012; Camasso et al., 1999; Turturro et al., 1997). This study also contributes by presenting a possible explanation for the inconclusiveness of other studies on this topic. While our findings are highly statistically significant because of the extraordinarily large sample of directly affected women, the effect size we find is relatively small. We find an income elasticity of welfare recipients’ fertility of 0.38.Footnote 22 The income elasticity found by studies about general populations is usually much larger. For example, Milligan (2005) estimates a 16.9% increase in fertility as a response to a 4.3% increase in income (elasticity of 3.93), González (2013) finds a 6% increase in fertility as a response to an 8.3% increase in income (elasticity of 0.72) and Cohen et al. (2013) estimate a 9.6% decrease in fertility due to a 3.3% decrease in income (elasticity of 2.91). Thus, while a fertility response is found among welfare recipients, it seems to be weaker than that of general populations. The smaller an effect is, the more statistical power is required to detect it. Accordingly, if, as we find, welfare recipients’ fertility is not very responsive to income changes, the scarcity of large data sets focused on welfare recipients might explain the inconclusiveness of former studies.

Our findings provide evidence that welfare recipients adapt their fertility decisions less strongly to a welfare cut than general populations adapt their fertility decisions to child benefit increases. The evidence from this study is important for policy makers because it speaks against the widely held assumption that the fertility patterns of welfare recipients might be excessively motivated by financial concerns. The opposite seems to be the case. This study does not determine the optimal level of child-related welfare benefits; however, it does show that concerns about an excessive fertility reaction should not factor into the deliberations of setting such benefit levels.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection regulations of the German Federal Employment Agency but can be accessed at the data center of the Institute of Employment Research on reasonable request.

Notes

Since the 1990s, nearly half of the states in the US have denied additional cash assistance to low-income mothers who have more children while receiving welfare. Over time, some of them retracted these policies. In 2018 there were 17 states which applied some type of family cap policy (Urban Institute, 2018).

For an overview of studies, see Table 1.

For example, the U.S. Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) includes only 458 unmarried women with children who received welfare benefits in their fertile age (Ryan et al., 2006).

We consider mothers who received welfare before the reform, still received it long after the reform and have at least one previous child.

Elasticity is calculated by dividing the 6.8% fertility reduction by the 18% average household income reduction.

We discuss the previous literature in detail in section "Literature review".

In addition, on strand of literature investigates the effects of in-kind transfers, such as Medicaid, on welfare recipients’ fertility, finding positive effects on the intensive fertility margin (e.g., Groves et al., 2018).

This amount adds up to $7344 for each child, as the additional 34$ is paid every month until the child turns 18.

In terms of the welfare system, a household is defined as people who live together and are either blood related or have a special care relation with each other. This special care relation can exist between spouses, cohabitating couples, or between an adult and his/her spouse’s children.

Welfare benefits also cover the costs of compulsory health insurance.

The data sets are Leistungshistorik Grundsicherung (LHG) and Integrierte Erwerbsbio-graphien (IEB). The LHG tracks the benefits received by households receiving welfare and the IEB is a register of all dependent employment in Germany. We use version 13.00.00 of the LHG and version 09.00.00 of the IEB.

The individual woman is the unit of observation in our analysis. If more than one woman in the relevant age range lives in a household, each of them contributes to the data with individual observations.

Still, also in the restricted sample, there are some women left who were only on welfare for two months over the 12 observed years—one month before January 2010 and one month between December 2016 and April 2017. In the restricted sample these were only 1.2% of women, while 21% received welfare the entire time we observe them. Among the 3.2 million excluded women 23% received welfare for merely one month during this time and 1.3% received welfare for the entire time. The median percentage of months with welfare receipt for the restricted vs. unrestricted samples lay at 18.5% vs. 82%.

We measure women’s education by their secondary school degree. The German school system is divided into three tracks, which differ in how academically challenging the education is. The basic and the middle track both take 10 years of schooling and qualify for apprenticeships. The middle degree additionally qualifies for entering universities of applied sciences. The highest degree requires 12 to 13 years of schooling and additionally qualifies for entering university. Though we also have information on apprenticeships and tertiary education, we do not use it in our analysis. Higher education is more endogenous to fertility than secondary education, which is usually finished between ages 16 and 19.

We cannot estimate the effect of the reform on abortions because there is no data on abortions that specifies whether the woman received welfare benefits.

We present results including the months January 2011 to March 2011 in Table 5, Column 6. The result is very similar to our baseline specification.

The German birth rate depicted in the figure also contains first births, because we have no data about parity specific birth rates for Germany as a whole.

If, instead of using the 2010 average, we took the average birth rate of the entire pre-reform period as a reference point, this would be a misrepresentation. β identifies the immediate drop between December 2010 and April 2011 rather than the mean difference between 2005–2010 and 2011–2016. Using the value from December 2010 would be a misrepresentation as well because it would base the scaling on the value of a month of year associated with a low birth rate.

Unfortunately, the nature of our data does not allow us to investigate this aspect as we cannot analyse first births (see Online Appendix B).

Apart from changing the bandwidth, the results reported here are estimated with a slightly different functional form. Here, the quadratic pre- and post-trends are excluded because including them together with the month of year fixed effects leads to multicollinearity for bandwidths up to 6 years. The results for the estimation including the quadratic trends are reported in Table A.3 in Online Appendix A.

The grouping is by age at observation. This means a woman can count into different groups as she ages.

6.8% fewer births as a reaction to household income reduction of 18%. 6.8/18 ≈ 0.38.

References

Argys, L., Averett, S., & Rees, D. I. (2000). Welfare generosity, pregnancies and abortions among unmarried AFDC recipients. Journal of Population Economics, 13(4), 569–594.

Azmat, G., & González, L. (2010). Targeting fertility and female participation through the income tax. Labour Economics, 17(2010), 487–502.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In U.-N. Bureau (Ed.), Demographic and economic change in developed countries: A conference of the Universities - National Bureau Committee for Economic Research (Vol. 11, pp. 209–231). Princeton University Press.

BEEG. (2010). Bundeselterngeld- und Elternzeitgesetz Edition of December 9, 2010. Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2010 Part 1, 1885 ff.

Berrington, A. (2004). Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Population Trends, 117, 9–19.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics., 119(1), 249–275.

BMAS. (2018). Grundsicherung für Arbeitsuchende. Sozialgesetzbuch SGB II. Fragen und Antworten. Broschüre, Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (BMAS), Bonn. Retrieved October 17, 2018 from https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/PDF-Publikationen/a430-grundsicherung-fuer-arbeitsuchende-sgb-ii.pdf

Brewer, M., Ratcliffe, A., & Smith, S. (2012). Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK. Journal of Population Economics, 25(1), 245–266.

Bundesregierung - Presse- und Informationsamt. (2010). Pressekonferenz Bundes-kanzlerin Merkel und Bundesminister Westerwelle zu den Ergebnissen der Kabinettsklausur. Retrieved October 24, 2018 from https://archiv.bundesregierung.de/archiv-de/dokumente/pressekonferenz-bundeskanzlerin-merkel-und-bundesminister-westerwelle-zu-den-ergebnissen-der-kabinettsklausur-846786

Camasso, M., Harvey, C., Jagannathan, R., & Killingsworth, M. (1999). New Jersey’s Family Cap and Family Size decisions: Some findings from a 5-year evaluation. Rutgers University.

Cohen, A., Dehejia, R., & Romanov, D. (2013). Financial incentives and fertility. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(1), 1–20.

Cygan-Rehm, K. (2016). Parental leave benefit and differential fertility responses: Evidence from a German reform. Journal of Population Economics, 29(1), 73–103.

Dyer, W., & Fairlie, R. (2004). Do family caps reduce out-of-wedlock births? Evidence from Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, New Jersey and Virginia. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 441–473.

Francesconi, M., & van der Klaauw, W. (2007). The socioeconomic consequences of “In-Work” benefit reform for British lone mothers. Journal of Human Resources, 42(1), 1–31.

Gauthier, A. H. (2007). The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: A review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(3), 323–346.

González, L. (2013). The effect of a universal child benefit on conceptions, abortions, and early maternal labor supply. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(3), 160–188.

González, L., & Trommlerová, S. (2020). How the introduction and cancellation of a child benefit affected births and abortions. Barcelona GSE Working Paper Series Working Paper No 1153.

Groves, L., Hamersma, S., & Lopoo, L. M. (2018). Pregnancy, Medicaid expansions and fertility: Differentiating between the intensive and extensive margins. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 475–511.

Jagannathan, R., Camasso, M., & Killingsworth, M. (2004). New Jersey’s family cap experiment: Do fertility impacts differ by racial density? Journal of Labor Economics, 22(2), 431–460.

Joyce, T., Kaestner, R., Sanders, K., & Stanley, H. (2004). Family cap provisions and changes in births and abortions. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 475–511.

Kearney, M. S. (2004). Is there an effect of incremental welfare benefits on fertility behavior? A look at the Family Cap. Journal of Human Resources, 39(2), 295–325.

Laroque, G., & Salanié, B. (2014). Identifying the response of fertility to financial incentives. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 29(2), 314–332.

Loury, G. C. (2000). Preventing subsequent births to welfare recipients. In D. J. Besharov & P. Germanis (Eds.), Preventing subsequent births to welfare recipients. School of Public Affairs.

Milligan, K. (2005). Subsidizing the stork: New evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(3), 539–555.

Moffitt, R. (1998). The effect of welfare on marriage and fertility. In R. Moffitt (Ed.), Welfare, the family and reproductive behavior: Research perspectives (pp. 50–97). National Academy.

Nitsche, Christian. (2010). Opposition und Gewerkschaften kritisieren Kürzungspläne der Regierung. Clip in the national news (Tagesschau). Aired on ARD on June 7, 2010. Last accessed: Oct. 24, 2018 under: https://www.tagesschau.de/multimedia/video/video718670.html

NTV. (2010). Hartz-IV-Gesetz noch nicht beschlossen - Elterngeld bereits gekürzt. Online article on ntv.de. Last accessed on Oct. 24, 2010 under: https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Elterngeld-bereits-gekuerzt-article1667286.html

Raute, A. (2018). Can financial incentives reduce the baby gap? Evidence from a Reform in Maternity Leave Benefits, Journal of Public Economics, 169(2019), 203–222.

Riphahn, R., & Wiynck, F. (2017). Fertility effects of child benefits. Journal of Population Economics, 30(4), 1135–1184.

Ryan, S., Manlove, J., & Hofferth, S. (2006). State-level welfare policies and nonmarital subsequent childbearing. Population Research and Policy Review, 25, 103–126.

SGB II. (2003). Zweites Sozialgesetzbuch Edition of December 24, 2003. Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2003 Part 1, 2954 ff.

Spieker, Sandra. (2010). Wen trifft der Sparhammer? Online article on bild.de. Last accessed Oct. 24, 2018 under: https://www.bild.de/politik/2010/jetzt-schnueren-sie-das-groesste-sparpaket-aller-zeiten-12805646.bild.html

SZ. (2010). Kein bisschen Frieden. Online article on sueddeutsche.de. Last accessed Nov. 19, 2018 under: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/sparplaene-der-bundesregierung-kein-bisschen-frieden-1.954454

Tudor, S. (2020). Financial incentives, fertility and early life child outcomes. Labour Economics, 64(2020), 101839.

Turturro, C., Benda, B., & Turney, H. (1997). Arkansas welfare waiver demonstration project, final report (July 1994 through June 1997). University of Arkansas at Little Rock, School of Social Work.

Urban Institute. (2018). Table IV.B.1. Family cap policies, July 2018. Last accessed Aug. 21, 2020 under: https://wrd.urban.org/wrd/tables.cfm

Wallace, G. L. (2009). The effects of family caps on the subsequent fertility decisions of never-married mothers. Journal of Population Research, 26(1), 73–101.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge helpful comments received at the 2019 conferences of the SEHO (Lisbon), the ESPE (Bath Spa) and EALE (Uppsala) and the 2020 SOLE (Berlin) conference. We thank Regina Riphahn and Libertad Gonzales for their support and helpful comments. Furthermore, we thank two anonymous referees for their many helpful comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sandner, M., Wiynck, F. The Fertility Response to Cutting Child-Related Welfare Benefits. Popul Res Policy Rev 42, 25 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09757-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09757-3