Abstract

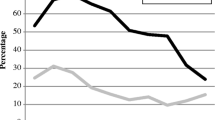

An estimated 7.8 million people live and work in the United States without authorized status. We examined the extent to which legal status makes them vulnerable to employment discrimination despite technically being protected under labor laws. We used three decades of data from the nationally representative National Agricultural Workers Survey, which provides four categories of self-reported legal status. We first investigated how legal status affected the wages and income of Mexican immigrant farmworkers using linear regression analyses. Then, we used Blinder-Oaxaca models to decompose the wage and income gap across the 1989 to 2016 period, categorized into five eras. Unauthorized farmworkers earned significantly lower wages and income compared to those with citizen status, though the gap narrowed over time. Approximately 57% of the wage gap across the entire period was unexplained by compositional characteristics. While the unauthorized/citizen wage gap narrowed across eras, the unexplained proportion increased substantially—from approximately 52% to 93%. That the unexplained proportion expanded during eras with increased immigration enforcement and greater migrant selectivity supports claims that unauthorized status functions as a defining social position. This evidence points to the need for immigration reform that better supports fair labor practices for immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use “unauthorized workers” to mean immigrants who do not have the legal paperwork required to be officially employed in the United States, yet hold employment. Although the term “undocumented” is often preferred by workers, our analysis is of legal status as it relates to employment, and so we believe “unauthorized” is a more appropriate term for this context.

The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) also asks a question about legal status; however, the unauthorized category is only available for analysis in the U.S. Census Bureau’s Restricted Data Centers. The papers that we are aware of that use the SIPP to ascertain differences by legal status do not use the restricted version of the variable, but rather construct a residual undocumented variable via a stepped process (see Hall et al., 2010, for an example).

Though SComm was replaced by the Priority Enforcement Program in 2014, the differences were considered marginal and President Trump reinstated the program in 2017.

The labor protections provided by FLSA and anti-discrimination statutes like Title VII of the Civil Rights Act apply to all persons “employed by an employer” (Civil Rights Act of 1964 1964). That unauthorized immigrants are thus persons entitled to protection by these laws is a matter the EEOC considers “settled principle” (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2002), even given the Hoffman Plastics decision, the United States Supreme Court Case Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. versus National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), 535 U.S. 137 (2002), in which the Court interpreted IRCA to mean that the punitive provisions of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) did not apply to workers who ‘knowingly broke immigration law’ and denied back pay to an undocumented worker laid off for participation in an union organizing campaign.

References

Abrego, L. J. (2016). Illegality as a source of solidarity and tension in Latino families. Journal of Latino-Latin American Studies (JOLLAS), 8(1), 5–21.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Arenas-Arroyo, E., & Sevilla, A. (2020). Labor market impacts of states issuing of driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants. Labour Economics, 63(April), 101805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101805.

Bansak, C., & Raphael, S. (2001). Immigration reform and the earnings of latino workers: Do employer sanctions cause discrimination? Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 54(2), 275–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2696011.

Bloomekatz, R. (2006). Rethinking immigration status discrimination and exploitation in the low-wage workplace comment. UCLA Law Review, 54, 1963–2010.

Borjas, G. J., & Cassidy, H. (2019). The wage penalty to undocumented immigration. Labour Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.101757.

Briggs, V. M., Jr. 1975. Mexican Migration and the U.S. Labor Market: A Mounting Issue for the Seventies. Studies in Human Resource Development 3. Austin, TX: Center for the Study of Human Resources, The University of Texas at Austin.

Chiswick, B. R. (1984). Illegal aliens in the United States labor market: Analysis of occupational attainment and earnings. The International Migration Review, 18(3), 714–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/2545894.

Chiswick, B. R. (1988). Illegal immigration and immigration control. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(3), 101–15.

Civil Rights Act of 1964. (1964). 42. Vol. 2000e. https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/titlevii.cfm

Cornelius, W. A., & Aguayo, S. (1978). La Migración Ilegal Mexicana a Los Estados Unidos: Conclusiones de Investigaciones Recientes, Implicaciones Políticas y Prioridades de Investigación. Foro Internacional, 18(3), 399–429.

Davila, A. E., & Mattil, J. P. (1984). Do Workers Earn Less Along the U.S.–Mexico Border? Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Research Paper, no. 8403.

De Genova, N. P. (2002). Migrant ‘illegality’ and deportability in everyday life. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31(1), 419–47. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085432.

De ong, G. F., & Madamba, A. B. (2001). A double disadvantage? Minority group, immigrant status, and underemployment in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 82(1), 117–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/0038-4941.00011.

Desmond, M. (2014). Relational ethnography. Theory and Society. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-014-9232-5.

Donato, K. M., Durand, J., & Massey, D. S. (1992). Changing conditions in the US labor market: Effects of the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. Population Research and Policy Review, 11(2), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00125533.

Donato, K. M., & Massey, D. S. (1993). Effect of the immigration reform and control act on the wages of Mexican migrants. Social Science Quarterly, 74(3), 523–41.

Donato, K. M., Wakabayashi, C., Hakimzadeh, S., & Armenta, A. (2008). Shifts in the employment conditions of Mexican migrant men and women: The effect of U.S. immigration policy. Work and Occupations, 35(4), 462–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888408322859.

Durand, J., Massey, D. S., & Pren, K. A. (2016). Double disadvantage: Unauthorized Mexicans in the U.S. labor market. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 666(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216643507.

Elder, T. E., Goddeeris, J. H., & Haider, S. J. (2010). Unexplained gaps and Oaxaca? Blinder decompositions. Labour Economics, 17(1), 284–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.11.002.

Fan, M., Pena, A. A., & Perloff, J. M. (2016). Effects of the great recession on the U.S. agricultural labor market. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 98(4), 1146–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaw023.

Fang, H., & Moro, A. (2010). Theories of Statistical Discrimination and Affirmative Action: A Survey. NBER Working Paper 15860. Cambridge, MA. http://www.nber.org/papers/w15860.pdf

Fogel, W. (1977). Illegal alien workers in the United States. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 16(3), 243–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.1977.tb00091.x.

Gleeson, S. (2010). Labor rights for all? The role of undocumented immigrant status for worker claims making. Law & Social Inquiry, 35(3), 561–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2010.01196.x.

Hadley, E. M. (1956). A critical analysis of the wetback problem. Law and Contemporary Problems, 21(2), 334–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/1190507.

Hall, M., Greenman, E., & Farkas, G. (2010). Legal status and wage disparities for Mexican immigrants. Social Forces, 89(2), 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0082.

Hamilton, E., & Hale, J. M. (2016). Changes in the transnational family structures of Mexican farm workers in the era of border militarization. Demography, 53(5), 1429–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0505-7.

Hertz, T., & Zahniser, S. (2013). Is there a farm labor shortage? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 95(2), 476–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aas090.

Houstoun, M. F. (1983). Aliens in irregular status in the United States: A review of their numbers, characteristics, and role in the U.S. labor market. International Migration (Geneva, Switzerland), 21(3), 372–414.

Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). (1986). 100. Vol. 3359. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-100/pdf/STATUTE-100-Pg3445.pdf

Isé, S., & Perloff, J. M. (1995). Legal status and earnings of agricultural workers. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 77(2), 375–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1243547.

Jann, B. (2008). The blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. The Stata Journal, 8(4), 453–79.

Kandel, W. A., & Donato, K. M. (2009). Does unauthorized status reduce exposure to pesticides? Evidence From the National Agricultural Workers Survey. Work and Occupations, 36(4), 367–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888409347599.

Kim, S., Egerter, S., Cubbin, C., Takahashi, E. R., & Braveman, P. (2007). Potential implications of missing income data in population-based surveys: An example from a postpartum survey in California. Public Health Reports, 122(6), 753–63.

Kossoudji, S. A., & Cobb-Clark, D. A. (1996). Finding good opportunities within unauthorized markets: U.S. occupational mobility for male LATINO workers. International Migration Review, 30(4), 901–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2547597.

Kossoudji, S. A., & Cobb-Clark, D. A. (2002). Coming out of the shadows: learning about legal status and wages from the legalized population. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(3), 598–628. https://doi.org/10.1086/339611.

Krogstad, J. M., Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2018). 5 facts about illegal immigration in the U.S. Pew Research Center (blog). November 28, 2018. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/11/28/5-facts-about-illegal-immigration-in-the-u-s/

Lofgren, Z. (2019). Agricultural Worker Program Act of 2019. https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr641/BILLS-116hr641ih.pdf

Massey, D. S. (1987). Do undocumented migrants earn lower wages than legal immigrants? New evidence from Mexico. International Migration Review, 21(2), 236–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546315.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Malone, N. J. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, D. S., & Gelatt, J. (2010). What happened to the wages of Mexican immigrants? Trends and Interpretations. Latino Studies, 8(3), 328–54. https://doi.org/10.1057/lst.2010.29.

Massey, D. S., & Gentsch, K. (2014). Undocumented migration to the United States and the Wages of Mexican immigrants. International Migration Review, 48(2), 482–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12065.

Menjívar, C. (2014). The ‘Poli-Migra’: Multilayered legislation, enforcement practices, and what we can learn about and from today’s approaches. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(13), 1805–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214537268.

Migration Policy Institute. (2013a). Mexican-Born Population Over Time, 1850-Present. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/us-immigration-trends

Migration Policy Institute. (2013b). U.S. Immigrant Population and Share over Time, 1850-Present. U.S. Immigration Trends. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/us-immigration-trends

National Immigration Law Center. (2011). The History of E-Verify. National Immigration Law Center. https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/e-verify-history-rev-2011-09-29.pdf

Neumark, D. (1988). Employers’ discriminatory behavior and the estimation of wage discrimination. Journal of Human Resources, 23(3), 279–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/145830.

North, D. S., & Houstoun, M. F. (1976). The Characteristics and Role of Illegal Aliens in the U.S. Labor Market: An Exploratory Study. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED133420

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male–female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14(3), 693–709. https://doi.org/10.2307/2525981.

O’Donnell, O., van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaff, A., & Lindelow, M. (2007). Explaining Differences between Groups: Oaxaca Decomposition. In Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data: A Guide to Techniques and Their Implementation, 147–57. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-6933-3

Padilla, Y. C., Scott, J. L., & Lopez, O. (2014). Economic insecurity and access to the social safety net among latino farmworker families. Social Work, 59(2), 157–65.

Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2015). Share of Unauthorized Immigrant Workers in Production, Construction Jobs Falls Since 2007. Hispanic Trends Project. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/03/26/share-of-unauthorized-immigrant-workers-in-production-construction-jobs-falls-since-2007/

Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2018). U.S. Unauthorized Immigration Total Lowest in a Decade | Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2018/11/27/u-s-unauthorized-immigrant-total-dips-to-lowest-level-in-a-decade/

Passel, J. S., Cohn, D., & Gonzalez-Barrera, A. (2012). Net migration from Mexico falls to zero—And perhaps less. Pew Research Center.

Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D., Krogstad, J. M., & Gonzalez-Barrera, A. (2014). As Growth Stalls, Unauthorized Immigrant Population Becomes More Settled. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/09/03/as-growth-stalls-unauthorized-immigrant-population-becomes-more-settled/

Pena, A. A. (2010). Legalization and immigrants in U.S. agriculture. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 10(1), 1935–1682. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2250.

Pena, A. A. (2010). Poverty, legal status, and pay basis: The case of U.S. agriculture. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 49(3), 429–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2010.00608.x.

Ranney, S., & Kossoudji, S. (1983). Profiles of temporary Mexican labor migrants to the United States. Population and Development Review, 9(3), 475–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/1973319.

Rivera-Batiz, F. L. (1999). Undocumented workers in the labor market: An analysis of the earnings of legal and illegal Mexican immigrants in the United States. Journal of Population Economics, 12(1), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001480050092.

Saucedo, L. M. (2006). The employer preference for the subservient worker and the making of the brown collar workplace. Ohio State Law Journal, 67, 74.

Smith, T. (1991). An analysis of missing income information on the general social surveys. 71. GSS Methodological Report. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. http://gss.norc.org/Documents/reports/methodological-reports/MR071%20An%20Analysis%20of%20Missing%20Income%20Information%20on%20the%20GSS.pdf

Taylor, J. E. (1992). Earnings and mobility of legal and illegal immigrant workers in agriculture. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 74(4), 889–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1243186.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Table A-1. Employment status of the civilian population by sex and age. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpsatab1.htm

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2016). Official USDA food plans: Cost of food at home at four levels, November 2016. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (2018). Secure Communities. March 2018. https://www.ice.gov/secure-communities

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, & U.S. Department of Labor. (2011). Revised memorandum of understanding between the Departments of Homeland Security and Labor Concerning Enforcement Activities at Worksites. https://www.dol.gov/asp/media/reports/dhs-dol-mou.pdf

U.S. Department of Labor. (1989). The National Agricultural Workers Survey. U.S. Department of Labor, Employment & Training Administration (ETA). http://www.doleta.gov/agworker/naws.cfm

U.S. Department of Labor. (2009). The National Agricultural Workers Survey, Part B: Collection of Information Employing Statistical Methods. 1205–0453. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.doleta.gov/naws/pages/methodology/docs/NAWS_Statistical_Methods_AKA_Supporting_Statement_Part_B.pdf

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2002). Directives Number 915.002: Rescission of Enforcement Guidance on Remedies Available to Undocumented Workers Under Federal Employment Discrimination Laws. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/undoc-rescind.html

Villarreal, A. (2014). Explaining the decline in Mexico–US migration: The effect of the great recession. Demography, 51(6), 2203–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0351-4.

Waldinger, R., & Lichter, M. I. (2003). How the other half works: Immigration and the social organization of labor. 1st ed. University of California Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ppzw7.

Ybarra, V. D., Sanchez, L. M., & Sanchez, G. R. (2016). Anti-immigrant anxieties in state policy: The great recession and punitive immigration policy in the American States, 2005–2012. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 16(3), 313–39.

Funding

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, J., Hale, J.M. & Padilla, Y.C. Immigration Status and Farmwork: Understanding the Wage and Income Gap Across U.S. Policy and Economic Eras, 1989–2016. Popul Res Policy Rev 40, 861–893 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09652-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09652-9