Abstract

How does intergenerational educational mobility change under educational expansion? This paper examines this question in Mexico, which enacted two important school expansion plans between 1959 and 1992. Using the 2011 Mexican Social Mobility Survey, I analyze how intergenerational mobility changes under different phases of expansion reform, and how do these trends vary according to the particular stage of the schooling process. Main findings indicate that mobility patterns are not stalled across cohorts, as reproduction theories predict. However, they do not reflect equalization at all levels of education either, as modernization hypotheses anticipate. Expansion reforms, especially the “11-year plan,” are associated with positive trends in mobility in primary and lower-secondary schooling, but also with a decrease in intergenerational mobility at higher levels of education. Thus, these findings are consistent with the maximally maintained inequality hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The countries included in the study were the U.S, the Federal Republic of Germany, England and Wales, Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Japan, Taiwan, Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia.

Subsequent theories have also incorporated the role of qualitative differences within each particular level of schooling as a mechanism through which upper-class families ensure their advantage in the educational attainment process (Lucas 2001). Yet this mechanism is beyond the scope of the present article.

Primary education comprises 6 years. Secondary education consists of other 6 years, which include three years of lower secondary and three years of upper secondary.

Specifically, those who answered “Pre-school or Pre-kinder” or “None/I did not go to school” were classified as having “Less than Primary.” Moreover, those who responded “General Secondary” and “Technical Secondary” were classified as having “Some Secondary,” as these grades correspond to Lower-secondary education according to the ISCED standards. Then, “General Preparatory” or “Technical Preparatory” was considered as “Complete Secondary.” Respondents who answered “Technical Education with some Primary” were classified as “Some Secondary” (If the respondent reported less grades than needed to complete this education level or did not have a certificate of completion, their level of education was considered as “Completed Primary”), and those who responded “Technical Education with some Secondary” (If the respondent reported less grades than needed to complete this education level or did not have a certificate of completion, their level of education was considered as “Some Secondary.”) were coded as “Complete Secondary.” Finally, those who responded “Normal” (This category refers to the “Normal School of Education” which trains individuals to become school teachers in Mexico), “Professional,” or “Postgraduate” were classified as having “Some Postsecondary.”

I did not include father’s ISEI in the creation of these profiles, given that this variable was not interacted by birth cohort in the preferred model.

In the case of multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE), Rubin’s recommendation is to include all potentially relevant variables for predicting X in the multiple imputation model (Rubin 1996). The key idea is to use all available information that enhances the prediction of the missing cases, usually this includes the dependent variable of the main analysis. Following these recommendations, the imputation model for these variables included all the predictors of my substantive models, all dependent variables, and all sample design variables (Van Buuren et al. 1999; Little and Rubin 2002). Also, I included a rich set of other measures that theoretically could predict the missingness of these variables, such as age, parental assets, and other socioeconomic characteristics of the parent’s household. This procedure, which included the creation of 10 new datasets, resulted in the imputation of 97% (2080 observations) of the missing cases corresponding to father’s ISEI, 94% (960 observations) of the missing cases in mother’s education, and 96% (1392 observations) of missing cases in father’s education.

Implemented in Stata using the package seqlogit (Buis 2011).

In addition, I also estimated a baseline model that included an interaction term between gender and parent’s education to check whether the role of parental education varies by gender of the offspring. As Table 8 in the Appendix shows, these interactions terms are very small in magnitude and nonsignificant across educational transitions. Indeed, t-tests do not reject the null hypothesis that these coefficients are equal to zero. Thus, I decided not to include an interaction between parental education and gender in the preferred model.

Two methodological remarks need to be made. First, I introduce each interaction term with birth cohorts one at a time. I start with (i) parent’s education, (ii) father’s ISEI, and then (ii) gender (Tables 10, 11 and 12 in the appendix). In the case of parent’s education, most interaction terms are insignificant with some notable exceptions. For primary completion, father’s education by cohort 1 has a positive and statistically significant effect compared to the base category (father’s education by cohort 5). Similarly, for achieving some postsecondary, the interaction between mother’s education by cohort 3 has a positive and statistically significant effect, while father’s education by cohort 3 has a negative and significant effect. In the case of father’s ISEI, interactions are small and insignificant. In contrast, gender by cohort 1 interactions has a sizable and negative effect compared to the base category for almost all transitions. Second, in order to have more parsimonious models, I decided not to include interaction terms between father’s ISEI and birth cohorts as neither of these terms significantly improved model fit (This according to a t test performed for each outcome). The results of the model that includes all interaction terms between family background predictors and gender with birth cohorts are presented in Table 13 in the appendix.

As seen in Fig. 8, point estimates for women born in cohort 1 have extremely high confidence intervals. This is partly because only 12 female respondents from this cohort attained some postsecondary education, which makes this outcome a rare event. Given that these predictions might be especially unstable, I decided not to consider them as the initial benchmark to test if they were statistically significant differences between cohorts.

Given that the seqlogit package in Stata does not allow for the inclusion of survey strata, estimates for the model with no unobserved heterogeneity contains small differences with the estimates of our preferred model in Table 4.

The exception being those in the secondary completion model, where cohort 1 loses significance in the last scenario.

References

Allison, P. (2001). Missing data Sage University papers on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Behrman, J., Garivia, A., & Szekely, M. (2001). Intergenerational mobility in Latin America. Economia, 2, 1–31.

Beller, E. (2009). Bringing intergenerational social mobility research into the 21st century: Why mothers matter. American Sociological Review, 74, 507–528.

Biblartz, T., & Raftery, A. (1999). Family structure, educational attainment, and socioeconomic success: Rethinking the “Pathology of Matriarchy”. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 321–365.

Binder, M., & Woodruff, C. (2002). Inequality and intergenerational mobility in schooling: The case of Mexico. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 50, 249–267.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: Towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society, 9, 275–305.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243.

Breen, R., Luijkx, R., Muller, W., & Pollak, R. (2009). Non-persistent inequality in educational attainment: Evidence from eight European countries. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 1475–1521.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage.

Buis, M. L. (2011). The consequences of unobserved heterogeneity in a sequential logit model. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29, 247–262.

Caballero, A., & Medrano, S. (1981). El Segundo Periodo de Torres Bodet, 1958-1964. In Historia de la Educación Publica en México. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Cameron, S. V., & Heckman, J. J. (1998). Life cycle schooling and dynamic selection bias: Models and evidence for five cohorts of American males. Journal of Political Economy, 28, 186–208.

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., et al. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Creighton, M., & Park, H. (2010). Closing the gender gap: Six decades of reform in Mexican education. Comparative Education Review, 54, 513–537.

Creighton, M. J., Post, D., & Park, H. (2016). Ethnic inequality in Mexican education. Social Forces, 94, 1187–1220.

De Graaf, P. M., & Ganzeboom, H. B. G. (1993). Family background and educational attainment in the Netherlands of 1891–1960 birth cohorts. In Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Deng, Z., & Donald, J. (1997). The impact of the cultural revolution on trends in educational attainment in the People’s Republic of China. American Journal of Sociology, 103, 391–428.

Erikson, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (1996). The Swedish context: Educational reform and long-term change in educational inequality. In Can Education (Ed.), Be equalized?. The Swedish Case in Comparative Perspective Boulder: Westview Press.

Evenhouse, E., & Reilly, S. (1994). A sibling study of stepchild well-being. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 248–276.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21, 1–56.

Gerber, T. (2000). Educational stratification in contemporary Russia: Stability and change in the face of economic and institutional crisis. Sociology of Education, 73, 219–246.

Gerber, T., & Hout, M. (1995). Educational stratification in Russia during the Soviet period. American Journal of Sociology, 101, 611–660.

Guao, M., & Wu, X. (2010). Trends in educational stratification in a reform-era: China 1981–2006. In C. Suter (Ed.), Inequality beyond globalization: Economic changes, social transformations and the dynamics of inequality. Berlin: Lit Verlag Munster.

Hauser, R. M., & Feathermann, D. L. (1976). Equality of schooling: Trends and prospects. Sociology of Education, 49, 99–120.

Henz, U., & Maas, I. (1995). Chancengleichheit durch die Bildungsexpansion? Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 47, 605–633.

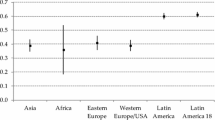

Hertz, T., Jayasundera, T., Piraino, P., Selcuk, S., Smith, N., & Verashchagina, A. (2008). The inheritance of educational inequality: International comparisons and fifty-year trends. Advances in Economic Analysis & Policy, 7, 1935–1682.

Hout, M., & Dohan, D. P. (1996). Two paths to educational opportunity: Class and educational selection in Sweden and the United States. In R. Erikson & J. O. Jonsson (Eds.), Can education be & equalized? The Swedish case in comparative perspective. Boulder: Westview Press.

Jennings, J. L. (2010). School choice or schools’ choice? Managing in an era of accountability. Sociology of Education, 83, 227–247.

Kaufman, J. C., Kaufman, S. B., & Plucker, J. A. (2013). Contemporary theories of intelligence. In D. Reisberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kent, R. (1998). Institutional reform in Mexican higher education: Conflict and renewal in three public universities. Working Paper EDU-102

Kerckhoff, A. C., & Trott, J. M. (1993). Educational attainment in a changing educational system: The case of England and Wales. In Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Lindbekk, T. (1998). The education blacklash hypothesis: The Norwegian experience 1960–1992. Acta Sociologica, 41, 151–162.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley.

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690.

MacLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. (1994). Growing up wit a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mare, R. (1980). Social background and school continuation decisions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 75, 295–305.

Mare, R., & Chang, H.-C. (2006). Family attainment norms and educational stratification in the United States and Taiwan: The effects of parents’ school transitions. In S. Morgan, D. Grusky, & G. S. Fields (Eds.), Mobility and Inequality. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Marteleto, L., Gelber, D., Hubert, C., & Salinas, V. (2012). Educational inequalities among Latin American adolescents: Continuities and changes over the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30, 352–375.

Parrado, E. A. (2005). Economic restructuring and intra-generational class mobility in Mexico. Social Forces, 84, 733–757.

Post, D. (2001). Region, poverty, sibship, and gender inequality in Mexican education: Will targeted welfare policy make a difference for girls? Gender and Society, 15, 468–489.

Raftery, A., & Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform and opportunity in Irish education, 1921–1975. Sociology of Education, 66, 41–62.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Willms, J. D. (1995). The estimation of school effects. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 20, 307–335.

Reardon, S. F. (2016). School segregation and racial academic achievement gaps. RSF: Russell Sage Foundation. Journal of the Social Sciences, 5, 34–57.

Rodríguez Gómez, R. (1998). Expansión del sistema educativo superior en México 1970–1995. In M. Fresán Orozco (Ed.), Tres décadas de políticas del Estado en la Educación Superior. ANUIES: Mexico.

Rubin, D. (1996). Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91, 473–489.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

SEP (Secretaria de Educacion Publica). (1964). Obra educativa en el Sexenio 1958–1964. Mexico City: Secretaria de Educacion Publica.

Shavit, Y. (1993). From peasantry to proletariat: Changes in the educational stratification of Arabs in Israel. In Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Shavit, Y., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (Eds.). (1993). Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Solana, F., Reyes, R. C., & Bolaños, R. (2002). Historia de la educación pública en México. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52, 613–629.

Tieben, N., de Graaf, P. M., & de Graaf, N. D. (2010). Changing effects of family background on transitions to secondary education in the Netherlands: Consequences of educational expansion and reform. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 28, 77–90.

Torche, F. (2010). Economic crisis and inequality of educational opportunity in Latin America. Sociology of Education, 83, 85–110.

Torche, F. (2014). Intergenerational mobility and inequality: The Latin American case. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 619–642.

Torche, F. (2015). Intergenerational mobility and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 94, 563–587.

Treiman, D. J. (1970). Industrialization and social stratification. Sociological inquiry. Special Issue: Stratification Theory and Research, 40, 207–234.

Van Buuren, S., Boshuizen, H. C., & Knook, D. L. (1999). Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 18, 681–694.

Wolfle, L. M. (1985). Postsecondary educational attainment among whites and blacks. American Educational Research Journal, 22, 501–525.

World Bank. (2016). Country indicators. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator.

Acknowledgements

I specially want to thank Mike Hout, David Greenberg, Florencia Torche, and Lawrence Wu for their valuable feedback and guidance. I also thank Fundación Espinosa Rugarcía (ESRU) for providing me the 2011 Mexican Social Mobility Survey (MSMS). Research reported in this publication was supported by The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P2CHD047879. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Urbina, D.R. Intergenerational Educational Mobility During Expansion Reform: Evidence from Mexico. Popul Res Policy Rev 37, 367–417 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-018-9466-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-018-9466-4