Abstract

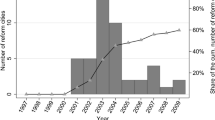

In the mid 1990s the Filipino government adopted a new export-led development policy in an attempt to attract new investments and lower the unemployment rates throughout the country. The central idea was to provide foreign investors more access to Filipino markets and labor by giving them investor tax breaks and lowering trade tariffs. In return, the government hoped that investors would bring large amounts of capital into designated areas thereby creating new jobs and stimulating the domestic economy. The Filipino created the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA) and Base Conversion Development Authority (BCDA) to manage the operation of the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) throughout the country. Between 1995 and 2005 PEZA and BCDA approved over 200 new SEZ that have created over four million jobs throughout the country. However, these jobs are concentrated in a small number of regions. This research uses a modified Harris-Todaro model and GIS techniques to examine the inter-regional migration response to the PEZA and BCDA programs’ geographically targeted investments. We show that areas with the highest job growth have high rates of in-migration while regions with low SEZ related investments have become migration-sending areas. In addition, our analysis shows that in-migration to SEZ affected areas has tended to surpass available jobs resulting in high unemployment. We show how the Harris-Todaro model in combination with GIS might be used to identify locations for future PEZA and BCDA investments that are less likely to result in regional population loss or growth in unemployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Based on the 2000 census, the Philippines is divided up into 14 regions, including the Metro Manila area. These regions are administrative divisions that serve primarily to organize the 81 provinces for administrative and statistical convenience. Although the number of regions has changed over time, this paper holds the 14 regions defined in the 2000 census constant throughout the paper.

The map below shows the location of all SEZ in the Philippines and divides the Philippines by region. The remainder of the paper will examine how SEZ have impacted the Philippines on a regional level, and are based on the 14 regions defined in the 2000 census. These regions are strictly for statistical geography and have no political offices associated with them. Senators, governors and other political officials are elected at the provincial level. However, regions are used by the census office and other national government agencies as a useful level for reporting sub-national statistics. As a result, the regional level was selected for analysis because consistent and accurate data are available from the Philippines government, while data at the provincial level are more difficult to obtain and are less reliable.

Note: Table 1 shows the number of jobs directly created within SEZ. It does not include peripheral jobs. In addition, there is a discrepancy between Fig. 1, the number of regions reporting SEZ, and Table 1, the number of regions reporting jobs. For example, Fig. 1 indicates that Region 11 had nine SEZ but zero jobs. Any discrepancy between Fig. 1 and Table 1 can be attributed to one of two reasons. (1) The SEZ in a region did not report the number of jobs created to BCDA or PEZA, or (2) the SEZ was approved by BCDA or PEZA, but investors later pulled out. The later is the case of a number of SEZ in Region 7 where plans to open shipyards to repair supertankers were relocated to Singapore (Philippines Business Week, Nov. 11, 2004).

We used the vital statistics method to estimate migration at the regional level between 1990 and 2005.

The Harris-Todaro model was developed to explain rural–urban migration in developing contexts. The terms “urban” and “rural,” hence are generic labels for origin and destination. The model is not limited for use on rural–urban migration.

Urban and rural populations are based on 2005 PopCen definitions and held constant through each time period. The Philippine National Statistics Coordination Board defines barangay (similar to a village or neighborhood) as urban if a barangay: (1) has a population size of 5,000 or more, or (2) has at least one establishment with a minimum of 100 employees, or (3) has 5 or more establishments with a minimum of 10 employees, and 5 or more facilities within the 2 km radius from the barangay hall. Using this definition, the total urban and rural populations were aggregated to the regional level for 1995, 2000 and 2005.

We acknowledge that there are limitations using ethnicity as means to support the models predicted findings. Due to the limitation of data, we do not know the specific origin of these new ethnic households. Many residents in Northern Mindanao, including Region 10, speak the Visayan language. We were not able to obtain more detailed migration and ethnicity census “public use data” from the NSO. However, while the data used to support the models findings are limited, results do show an increased south to north migration pattern consistent with the models findings and the theory of cumulative causation.

References

Bases Conversion Development Authority. (2001). Annual report 2000.

Bases Conversion Development Authority. (2006a). About the BCDA. Retrieved March, 19, 2006, from http://www.bcda.gov.ph.

Bases Conversion Development Authority. (2006b). Annual report 2005.

Bell, C. (1991). Regional heterogeneity, migration, and shadow prices. Journal of Public Economics, 46(1), 1–27.

ESRI. (2007). Understanding different kriging models. Retrieved September 6, 2007, from http://webhelp.esri.com/arcgisdesktop/9.2/index.cfm?TopicName=Understanding_different_kriging_models.

Fields, G. S. (1975). Rural-urban migration, urban unemployment and underemployment, and job-search activity in LDCs. Journal of Development Economics, 2(2), 165–187.

Guillermo, V. (1996). Checking out employment strategies. Manila: Press Foundation of Asia.

Harris, J. R., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis. The American Economic Review, 60(1), 126–142.

Issah, I., Khan, T. Y., & Sasaki, K. (2005). Do migrants react to infrastructure difference between urban and rural areas? Development of an extended Harris-Todaro model. Review of Urban and Regional Development Studies, 17(1), 68–88.

Makabenta, M. P. (2002). FDI location and special economic zones in the Philippines. Review of Urban and Regional Development Studies, 14(1), 59.

Massey, D. S. (1990). Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index, 56(1), 3–26.

Massey, D. S. (1999). Why does immigration occur? In C. Hirschman, P. Kasinitz, & J. DeWind (Eds.), The handbook of international migration: The American experience (pp. 34–52). New York: New Russell Sage Foundation.

National Statistical Coordination Board. (2001). 2000 Philippines statistical yearbook. Manila: National Statistical Coordination Board.

Philippines Congressional Planning and Budget Department. (2003). Economic and employment status report.

Philippines Economic Zone Authority. (2006a). About PEZA. Retrieved April, 23, 2006, from http://www.peza.ph.gov.

Philippines Economic Zone Authority. (2006b). Philippines special economic zones. Retrieved April 23, 2006, from http://www.peza.gov.ph.

Philippines Economic Zone Authority.(2006c). SEZ employment totals. Unpublished report.

Philippines National Census. (1997). Provincial profile: National capital region. Manila: National Statistical Board.

Philippines National Census. (1998a). PopCens 95. Manila: National Statistical Board.

Philippines National Census. (1998b). Socio-economic and demographic characteristics, 1995. Manila: National Statistical Board.

Philippines National Statistics Office. (2002). Philippines statistical yearbook, 2001. Manila: Bureau of the Census and Statistics.

Philippines National Census. (2005). Socio-economic and demographic characteristics, 2000. Manila: Bureau of the Census and Statistics.

Philippines National Census. (2006). Socio-economic and demographic characteristics, 2000. Manila: National Statistical Board.

Ringuet, D. J., & Estrada, E. (2003). Understanding the Philippines’ economy and politics since the return of democracy in 1986. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 25(2), 233.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1974). Alternative theories of wage determination and unemployment in LDC’s: The labor turnover model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 88(2), 194–227.

Tolentino, M. P. (1994). Developing agriculture toward sustainable industrialization. Economics and business in the Philippines (pp. 57–68). San Francisco: The Asia Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanders, S.R., Brown, D.L. The Migratory Response of Labor to Special Economic Zones in the Philippines, 1995–2005. Popul Res Policy Rev 31, 141–164 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-011-9220-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-011-9220-7