Abstract

One of Daniel Hogan’s lasting impacts on international demography community comes through his advocacy for studying bidirectional relationships between environment and demography, particularly migration. We build on his holistic approach to mobility and examine dynamic changes in land use and migration among small farm families in Altamira, Pará, Brazil. We find that prior area in either pasture or perennials promotes out-migration of adult children, but that out-migration is not directly associated with land-use change. In contrast to early formulations of household life cycle models that argued that aging parents would decrease productive land use as children left the farm, we find no effect of out-migration of adult children on land-use change. Instead, remittances facilitate increases in area in perennials, a slower to pay off investment that requires scarce capital, but in pasture. While remittances are rare, they appear to permit sound investments in the rural milieu and thus to slow rural exodus and the potential consolidation of land into large holdings. We would do well to promote the conditions that allow them to be sent and to be used productively to keep families on the land to avoid the specter of extensive deforestation for pasture followed by land consolidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This special issue of Population & Environment highlights Daniel Hogan’s lasting contribution to international demography through his advocacy and direct support for empirical studies of the relationship between demography and environment. In this paper, we build on two foci of Hogan’s writings, population mobility and bidirectional relationships between demography and environment, and we show results from an empirical project that received his institutional support for more than a decade.

In recent decades, Hogan highlighted migration as the most dynamic and influential component of contemporary demographic change (Hogan 1992, 2001; Hogan and Marandola 2005) and, therefore, key to understanding environmental change on short time scales. Hogan’s work further emphasizes that a complete understanding of demography and environment cannot privilege a single causal direction. That is, researchers must consider how population, specifically population mobility, affects the environment (P → E), and how environmental threats and changes induce population responses, including population redistribution and adaptation (E → P) (Hogan 1995, 1998). This paper builds toward such a complete understanding by focusing on one set of bidirectional empirical relationships: land-use predictors of migration and migration impacts on land-use change.

These relationships are context-specific, with social and economic institutions influencing the specific way in which variables are related (Hogan 2005). We seek in this paper both to bring a global literature on the linkages between migration, remittances and agriculture to the specific context of an aging frontier in the Brazilian Amazon and to bring a rich context-specific literature on land-use change in Amazonian frontiers into the changed context facing the second generation in the frontier. Past literature on demography and land-use change in the Amazon has focused on the role of changing labor availability and risk preferences over the household life cycle. This literature considers the out-migration of children of the household head to correspond to a period of consolidation of activities because of declining labor availability and to follow a period of higher risk tolerance because of excess labor available (McCracken et al. 1999; Walker 2003; Perz et al. 2006; VanWey et al. 2007). Our models allow us to explicitly test whether out-migration of adult children has such a lost-labor effect on land use. We complement this theoretical approach with literature from economic demography pointing to the role of migration in facilitating investments in capital-intensive or high-risk agriculture in developing country settings (Stark and Lucas 1988; Taylor et al. 2003; Wouterse and Taylor 2008; Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010), testing whether remittances are associated with investments in land expansion or expansion of the area in particular types of crops.

Our results show that productive land use can facilitate out-migration and that remittances can facilitate investment in high-pay off agriculture that might not be otherwise feasible due to scarce credit and off-farm high-wage employment. Further, even without remittances from migrants, households do not experience significant declines in productive land use with out-migration of adult children. While these children might leave because there is not enough work on the farm, we suggest that they might also remain tightly connected to the farm even after leaving, that their out-migration defined by a change in place of residence may in fact be more akin to a commute than to a migration. In doing so, we build on Daniel Hogan’s late-life call for a focus on the concept of mobility in place of that of migration (Hogan and Marandola 2005; Marandola and Hogan 2007).

Background and theoretical foundations

Frontier settlement and development in the Brazilian Amazon was driven by an initial inflow of land-seeking migrants from different parts of the country,Footnote 1 mainly the Southeast and Northeast regions, during the 1970s and by a rapid urbanization of regional cities from the mid-1980s on (Hogan et al. 2001). Studies suggest that population dynamics, at the regional level, changed from intra-regional to inter-regional,Footnote 2 as the frontier evolved with rapid urbanization and transformations in land use (Perz 2002; Hogan 2001; Hogan et al. 2008). Although net migration rates leveled off over time, internal migration became prominent as some frontiers reached structural limits for small-scale agriculture and as the second generation of original settlers saw the urban environment and off-farm employment as increasingly attractive livelihood options (Murphy 2001; Barbieri et al. 2009). In this context of stabilizing population size in the region, with low birth rates and low rates of in-migration, we seek to understand how initial land use by the first generation shapes the out-migration of the second generation and how that out-migration, in turn, modifies land use.

How land use affects out-migration of the adult children of farm owners is a traditional migration selectivity question. Across settings around the world, this type of migration has been framed in two ways. It is traditionally considered an individual-level decision of the (potential) migrant, based on push and pull factors (Lee 1966) or, more formally, on the economic returns to remaining in the origin versus moving, net of costs (Todaro 1969; Harris and Todaro 1970). Work in many developing countries in recent decades has indicated that this individual framework is limited and that migration of young adults is a whole family strategy to diversify risk and overcome credit constraints (Mendola 2008; Wouterse and Taylor 2008; Quisumbing and McNivel 2010). These two approaches have similar predictions about our focal relationship in this paper, between land use and migration, and our models do not provide a strong test to adjudicate between these theories.Footnote 3 We, therefore, review here common theoretical predictions for the importance of land use and empirical patterns of migrant selectivity and use those to consider patterns in our study area.

In the traditional push/pull model, one can think of “push factors” as limited opportunities for employment in the origin, in our case on the family farm. These are a function of factors constant across households (and, therefore, not formally analyzed) such as limited rural labor markets and of factors that vary across households such as land use and household size. “Pull factors” are then the opportunities in potential migration destinations, including urban employment, higher urban wages, available uncleared land, and amenities like health and education infrastructure (Padoch et al. 2008; Massey et al. 2010). These pull factors are present for everyone, but have different weights for different individuals and, therefore, produce migrant selectivity (Feliciano 2005). For example, we see ethnographically and in individual-level models in other work that women and men have different probabilities of migrating to urban areas because women have higher education and are advantaged relative to men in urban labor markets and disadvantaged in rural labor markets (Barbieri and Carr 2005; Resurreccion and Khanh 2007).

This paper focuses on land use as a push factor and as an indicator of wealth. Productive land provides employment for potential migrants, decreasing the push to leave, but also provides wealth, enabling the migrants to leave (VanWey 2005; Gray 2009). As found by VanWey (2005) and multiple subsequent authors across contexts (Yang and Choi 2007; Quisumbing and McNivel 2010; Robson and Nayak 2010), productive land is also an investment opportunity that cannot be invested in without access to capital. The remittances from migrants are one possible way to access such capital in the absence of functioning credit markets. Thus, productive land should encourage out-migration both because it is a resource on which families may draw to finance a migration and because remittances can subsequently be invested in it.

Turning to the impact of the migration on land use, we build on more focused Brazilian Amazonian research as well as international research. Much work at the micro-level in recent decades in the Amazon has stressed the role of migration in changing the household composition. This work on land-use change on small farms focuses on the role of the household life cycle, primarily on the labor constraints and consumption needs that change over time from the marriage of a young couple through childbearing and then to an almost empty nest (McCracken et al. 1999; Walker et al. 2002; Perz et al. 2006; Caldas et al. 2007). The pattern of results found suggests that young families clear and/or use larger areas and produce more extensively, while they have younger children and a shorter time horizon. During this time, labor is scarce (until children are able to help) and consumption needs are high. Thus, time horizons are short as farm owners work to meet current consumption needs and get ahead enough to plan for more long-term investments. As children age, labor becomes more plentiful and farm owners can make more long-term investments. During this period, they might extensify further or intensify, but the defining characteristic of this period in their life cycle is an investment in activities that will produce larger returns but might be more risky or require more time to pay dividends. Later, as children leave home or start their own families, the older generation pulls back on productive activities and/or gives over used land to children for their use. This literature suggests that the key effect of out-migration of adult children while the older generation maintains the farm will be a decrease in productive area, particularly in productive uses with a long time horizon (we will discuss this time dimension later in describing the study area).

The lost-labor effect of out-migration, however, presumes first that the out-migrants do not contribute labor to the farm and second the absence of labor markets and remittances. We argue that we may not see a decline in productive uses due to out-migration because these presumptions do not hold. Adult children continue to help on the farm after moving away. In Brazil and elsewhere, we see a pattern of migration as a livelihood strategy of the larger family that in which the moving of a family member represents more than the change in residence, but rather the expansion of the household boundaries over space (Mazzucato 2009). In addition, we have seen the rapid development of labor markets in the frontier (Browder and Godfrey 1997; Browder 2002), and remittances from migrants have the potential to allow farmers to purchase labor, a possibility that we test in models below.

We can look to literature elsewhere in the world to see that migration is often a response to the failure of credit markets and the associated need to access scarce cash (Stark 1991; Massey et al. 1993). This cash income meets a variety of needs, including increasing the level of consumption or smoothing consumption (Rosenzweig and Stark 1989; Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1993), as well as loosening household budget constraints to allow households to invest in agricultural (or business) activities that are higher risk or have a longer time until the household sees a return on the investment (De Brauw and Rozelle 2008). Empirical work from around the world demonstrates that remittances are a source of capital to finance the purchase of land, cars, businesses, or other investments (Massey et al. 1993; Ellis 1998; Taylor et al. 2003; Sana and Massey 2005; Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010). Migration, rather than simply representing a loss of labor, might improve farm productivity allowing investment in agricultural technology and/or crops with a higher return (Jokisch 2002; World Bank 2008).

Similarly, we know from other parts of the world that the absence of insurance markets in the face of high-risk agricultural production, as we see at any frontier, is also associated with migration as a risk-diversification strategy. Migrants can provide remittances in the case of failure on the farm, especially if they work in a location or economic sector subject to different exogenous shocks (Stark and Lucas 1988; Rosenzweig and Stark 1989). In addition, migration has been shown to facilitate risky investments through the provision of insurance (Yang and Choi 2007; Mazzucato 2009). The insurance function of migration is difficult to identify empirically, as it leads to remittances only the face of crop failure or other origin family crisis. The credit function of remittances, in contrast, should be readily identifiable in empirical models as a positive effect of remittances on the expansion of agricultural land and on the area devoted to the most capital-intensive crops.

Applying these arguments to the specific case of land-use change in the Altamira settlement area in the Brazilian Amazon, we argue that productive land use will have no effect or a positive effect on migration, because it represents wealth and investment possibilities and that remittances will encourage the expansion of agricultural land, primarily perennial production. We present the characteristics of the study area, including details underlying these expectations, in the following section.

Study area: Altamira, Pará, Brazil

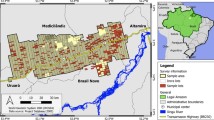

Data for our analyses come from a longitudinal study in the Altamira settlement area in the state of Pará, Brazil (Fig. 1). This area, which currently incorporates parts of Uruará, Medicilândia, Brasil Novo and Altamira municipalities, was initially settled (during the past century) during the 1970s when the TransAmazon highway was constructed through the city and on to the west. Settlers arrived from across Brazil to plots of land, most of which had 100% primary forest. Altamira was a model settlement area during the early years, with the government providing assistance to settlers in traveling to the settlement area and in clearing land and starting to produce (Moran 1981). Settlers, however, were not well-screened in all cases for past agricultural experience, and the government support lasted only a few years. For these reasons, early years were characterized by many farm failures, high malaria rates, and high rates of out-migration (Smith 1982). The area settled into a more stable pattern by the 1990s, with new areas still being opened, but more stable patterns of production and settlement (McCracken et al. 2002). There are currently two municipal seats in the area corresponding to the original settlement (Brasil Novo and Medicilândia). The presence of these local urban areas within the study area, and the proximity of the seat of Altamira, a sizeable and dynamic city, facilitates short-term migration and dual-residence households (Guedes et al. 2009a, c).

Biophysically, the region is characterized by rolling (but steep) topography and primarily oxisols (adequate but not ideal soils), with small patches of high quality soil or flat topography. The topography, combined with the rapid rainfall in the rainy season and the practice of building bridges of wood, lead to precarious transport systems. These are aggravated by variable levels of government maintenance of infrastructure. Given this setting, the most common productive land uses are annual food crops (manioc, beans, rice), pasture, and perennial cash crops (overwhelmingly cacao, with occasional black pepper or coffee). Annuals rarely represent more than a few hectares of a property, used only to supply the household and not for income generation. We thus focus our description here and our models on the pasture and perennial systems, and how they might relate to migration and remittances.

Pasture formation is labor-intensive, but can pay dividends quickly and is usually formed little by little over time using family labor. Our qualitative fieldwork over multiple seasons in the region shows a standard approach to the formation of pasture. Forest is cleared at a rate of less than five hectares per year, and annuals (rice, beans, and manioc) are planted for 1–3 years on cleared land, and then pasture grasses are planted (D’Antona et al. 2006). Larger trees felled during the clearing phase are used in the construction of fences and other necessary structures (Guedes 2010). In this way, using almost no capital, pasture is formed and expanded year after year. Pasture might be left without cattle if land clearing is speculative, or cattle might be stocked at the rate of 1 head per hectare. These cattle are a form of savings and low-requirement investment, and farmers can always sell the cattle quickly in the case of income shortfalls (Walker et al. 2000, 2002). The cattle also, however, provide low returns. Cattle raised on these pastures are destined for local and regional markets, as the North of Pará (and all of Pará at the time of the surveys) still has uncontrolled endemic foot-and-mouth disease.

Cacao, in contrast, is destined for international markets (usually via domestic markets) and has a higher return. It is also more capital intensive and has a much longer investment time before it produces. To arrive at a productive level of cacao production, both money and time are necessary. After clearing land, it is necessary to purchase seedlings, expensive enough to require either credit or substantial savings to permit purchase of enough to plant even a small area. Labor is needed to plant the seedlings and then care for them over 5 years until they begin producing fruit. This involves periodic weeding and treatments to prevent common pests. Once the trees begin producing fruit, farmers in our study area use sharecropping arrangements for the labor of harvest, cleaning and drying, thus avoiding an outlay of cash during that period. Before then, however, they must invest in the infrastructure for this period, including houses for the sharecroppers and a drying area (from basic cleared area with sheets of plastic to wooden platforms) for processing the beans. In our study area, it requires decades of investment to create a mature cacao plantation, with groves of trees of various ages (trees begin producing at 5 years, but peak production is at 10 years and then declines with age).

We use data on the changes over time in land use and household composition on farms with stable ownership over 7 years to assess the selectivity of migration based on baseline land use and to examine the land-use changes associated with that migration. Baseline interviews for this project were conducted with the owning household for a stratified random sample of 402 properties in the region, stratified by the time of initial settlement (based on satellite imagery). These interviews took place in 1997 and 1998. Follow-up interviews took place in 2005. Initial interviews focused on the household containing the owner of the property, while follow-up interviews focused on three groups. First, the previously interviewed owners were reinterviewed either on the same property or in a new house elsewhere in the study area. Second, the previously sampled properties were followed up through interviews with the current owner (of the same property or any piece of the previously interviewed property) and interviews with all resident households. Third, the children of the originally interviewed owner who had lived in the household of the owner in 1997/1998 were followed and interviewed wherever they lived in the region. In addition to these interviews, location information was collected about all previous owners and coresident children who had left the region. Transfer (money and support) information was also collected about all non-coresident children, regardless of follow-up status. We use these data to define a sample and create measures of migration, focusing on the out-migration of children.

Using these data, we now revisit our questions of the selectivity of migration and the impacts of migration on land use. Productive land area (pasture and perennials) in the baseline represents the wealth of the family and, therefore, the ability to finance a migration, but also represents a need for labor (though the need is relatively small in a mature cacao plantation or a completed ranch with hired cowboys). We, therefore, have no clear expectation for its effect on migration. In contrast, we have clear expectations of how migration and remittances might relate to land-use change. Migration should have either no effect or a negative effect on productive land area if migrants are excess labor or if they were needed, respectively. This effect should be counterbalanced by a positive effect of remittances on change in productive land use (pasture or perennials) if remittances are used to hire labor in the market to compensate for lost family labor. If, however, remittances are doing more than compensating lost labor and are increasing household budget flexibility and effectively acting as low interest credit, we would see this positive effect much more strongly on perennials than on pasture. Perennials require dramatically more capital and require an alternative source of income while waiting for the trees to produce, making the loosening of household budget constraints essential for the expansion of the area in perennials.

Measures

Our key variables are land use and number of out-migrants. We measure land use by aggregating the respondent’s reports on the area of the property in a variety of land uses. The questionnaire focused on locally important categories (pomar [orchard], pasto [pasture], roça [garden, usually mixed subsistence crops], mata [forest], capoeira/juquira [secondary growth on previously cleared land]). We then aggregated this into forest (including only primary forest, not older secondary growth), pasture (aggregating all reported pastures along with areas that were secondary growth, but were used as pasture), perennials (including cocoa, coffee, black pepper, and a few other less common crops), and annuals (gardens, rice, beans, manioc, and a few other less common crops). We did not use area in annuals as an outcome for land-use models because previous analyses showed little variance across properties in the area planted in annuals (VanWey et al. 2008). In contrast to the neighboring Uruará study area, where annual production is the most important land use (Walker et al. 2002), most households in our study area keep only approximately 3 hectares of land in annuals to meet immediate consumption needs, independent of other land use on the property (VanWey et al. 2007; Guedes 2010). We, therefore, present only models of land area in forest, pasture, and perennials.

Family out-migration between waves is a compilation of information from completed questionnaires and informants. We started by going to the property to look for the old owner and all the members reported as part of the original household in 1997/1998. We collected information on the current residence of any who no longer lived there. We obtained information on the current location of 398 of the previous owners of the 402 properties (two properties were inaccessible because of a bridge burning and we could find no information on the owners of the final two) and information about the vast majority of the previous household members. In some cases, the information was only that they were no longer in the study area, but in most cases we have information on the município (if in Pará) or state (if outside Pará) of current residence, and on whether it is in a rural or urban area of the município/state.Footnote 4 We combined information from owners and informants reported in this way with information about the location of children reported in the survey to determine the current location of children who were reported to be in the household in 1997/1998 and then calculated the number of such children in the household. We also created a dummy variable indicating whether the household had at least one out-migrant child.

To model whether remittances are the mechanism through which migration of children affects land-use change, we measure financial support given by children to the household. The survey asks about such transfers in the year preceding the survey. These transfers were operationalized in three ways: (1) as a dummy variable indicating whether the household received any financial support from at least one child in 2004; (2) as a count variable of the number of children making financial transfers to the household in 2004; and (3) as a continuous variable of the monetary value of total transfers in 2004. These variables were entered in three separate models of land-use change in order to determine whether the fact of remittance receipt from various children was important or whether the amount was essential for understanding land-use strategies.

Control variables in our analyses include the land use in 1997/1998, created in the same way as the 2005 land use. Control variables measured in 1997/1998 also include the proportion of the property in high fertility terra roxa soil (varying from 0 to 1), the age of household head (the property owner), the demographic composition of the household, the year of arrival of the household on the property, and the log of the household total income in the year prior to the interview. In operationalizing the demographic composition of the household, we tested a variety of measures based on the genders and detailed ages of all members; statistical tests (not shown) indicated no explanatory power was gained by using more complex measures than the number of adults, children, and elderly or the number of persons in the household. The year of arrival on the property is continuous. The total household income measure was created by combining information about total household monetary value of agricultural production sold in the previous year, off-farm income from all household members, and other income sources (such as social security benefits, pensions, and cash transfer social programs). Some households (8.24%) were missing information about production; for these, we imputed values based on other respondents who produced the same product.Footnote 5 Finally, we used the logarithmic form of income to account for an expected decreasing marginal effect of income on dependent variables.

Modeling strategy and sample

Our modeling strategy utilizes three types of models. First, to examine the selectivity of out-migration in terms of land use and other household characteristics, we estimate a Poisson regression of the number of out-migrants on the 1997/1998 characteristics of the household and property. Our analytical sample for this model includes 267 properties with the same owner in 1997/1998 and 2005 and with valid measures on all independent and control variables (including imputed income). This sample is a subset of 277 properties with the same owner in 1997/1998 and 2005 (excluding those sold or on which the owner died).Footnote 6 This analysis allows us to look at how migration in the interval between land-use measures is related to earlier land use, helping us understand selection into out-migration of young adults.

To identify the feedback, if any, from out-migration to land use, we separately examine the expansion of land owned and the changes in land use. We estimate a logistic regression model predicting whether a property is the same over the 1997/1998–2005 interval, or whether is consolidated with at least one other property (increases in size). Our analytical sample for models of the change in property size includes 259 observations. Because only eight properties were fragmented over the period, we excluded these properties from this analysis. In this model and in land-use models, out-migration and remittances are the key independent variables. We measure migration as the number of children who migrated out of the household in the 1997/1998–2005 interval and test models measuring remittances in three ways: a dummy variable for whether any of the out-migrant children send money, the number of out-migrant children who remit money to their parents, or the amount of money sent.

Finally, we estimate (for the sample of 267) seemingly unrelated regression (SUR)Footnote 7 models of the area in each of three uses in 2005: forest, pasture, and perennials, as well as Tobit models for the proportion of the property in each of the land use/cover classes in 2005. The use of scalar (SUR) and proportional (Tobit) models allows us to test for sensitivity of the impact of our key variables on land use. For these land-use models, we include a lagged dependent variable so the coefficients on covariates represent their relationship to the change in area (or proportion of the area) in a particular land use over the 1997/1998–2005 interval. In these models, we include a control variable measuring whether the property changed size in the interval.Footnote 8

For all our regression models, with the exception of SUR models,Footnote 9 we report bootstrap standard errors of the estimated coefficients. Simulation studies suggest that, in small samples, inference based on bootstrap standard error estimates may be considerably more accurate than inference based on closed-form asymptotic estimates (Gonçalves and White 2005).

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics on the sample of 267 used in our analyses. Sixty-one percent of the households in our sample had at least 1 child who left home between 1997/1998 and 2005. The number of out-migrant children varies from 0 to 7, but averages slightly over 1 child per household. Although migration is common among rural households in our Altamira study area, only 12% of households with at least one out-migrant child received any financial support. The average value of remittances per household was around R$65 (approximately 2005 US$24) for the 12 months prior to the interview.Footnote 10 This underestimates the importance of family transfers in the study area, as much of the support between family members takes the form of help with labor, food, medicine, or clothing (Guedes et al. 2009b). Because, however, this study focuses on the financial ability of transfers to overcome credit constraints, we exclude these other types of transfers in our analyses. The average household income was R$4,952 (approximately 1997 US$4,563). Households were relatively old on average, with a head who was 51 years old and had an average of five persons per household. These members were concentrated in the working age group (3.3 adults), with approximately three times as many children (1.3) as elderly people (0.5). This demographic structure is very similar to other agricultural frontiers of the Amazon (Barbieri and Carr 2005; Perz et al. 2006).

As described earlier, pasture is the main land use in our study areas, followed by perennials. Between 1997/1998 and 2005, there was a slight increase in perennials (two hectares), along with an increase of 14 hectares in pasture and a corresponding loss of 16 hectares of forest, suggesting that land conversion was mainly for commercial use (and not for subsistence). For just 9% of the properties, there was a change in property size, mainly consolidation (15 out of the 267). The proportion of the property with higher fertility soils averaged 22%, although there is a lot of variation within the study area (SD = 34%), with the alfisols (terra roxa) concentrated around the municipality of Medicilândia, in the center-west of our study area (Guedes 2010).

Results

Table 2 shows the results of our simple migration model. We focus on the effects of 1997/1998 land use on the number of adult children out-migrating to understand the selectivity of out-migration with respect to baseline land use. Control variables generally perform as expected, giving us confidence in our model. More migrants come from households with more adults at baseline and more come from households with elderly residents (parents who are older). More migrants come from households with lower income, but productive land area, both pasture and perennials, has a positive effect on migration. This suggests that cleared land serves as a proxy for wealth that facilitates out-migration rather than serving as a source of employment that keeps adult children down on the farm.

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression of property status (same size or larger size) in 2005 on household and property characteristics in 1997/1998, migration between 1997/1998 and 2005, and transfers in the year preceding the 2005 survey. This model tests whether migration and remittances are associated with expansion of production through land acquisition. Property expansion is positively related to area in perennials and area in pasture in 1997/1998, as was out-migration, suggesting that wealthy households are more able to both finance a migration and expand their land. Once controlling for these initial conditions, however, out-migration has a complex and unexpected relationship with land expansion. The number of out-migrants is positively related to expansion, but only if those migrants send no money home. The coefficient on the number of out-migrant children transferring is negative and much larger in absolute value than the coefficient on the number of out-migrant children, implying that expansion is less likely when children leave and send back money than when all children stay. It is possible that there is unobserved selectivity into remitting money that could explain this result; other work, using non-parametric approaches, has shown that children who move farther away and do not provide labor provide money instead, while children remaining close by and able to provide physical help do not send money (Quisumbing, and McNivel 2010; Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010; Robson and Nayak 2010). Thus, the higher likelihood of land expansion with non-remitting migrants might reflect the ability of these migrants to provide labor. We do not, however, have the sample size to test this in a regression framework and can only speculate.

Tables 4 (seemingly unrelated regression models) and 5 (Tobit regression models) show the relationships between household and property characteristics in 1997/1998, migration and transfers, and land uses. Migration has no significant relationship with any land use, showing no lost-labor effect, evidence consistent either with an argument that only excess labor leaves the farm or with an argument that migrants maintain their labor contributions on the farm. Our qualitative fieldwork and the high rate of labor help exchanged in our survey data suggest the second, but again we do not have an adequate sample to test this in a regression framework. Remittances, in contrast, show a statistically significant relationship to all land uses, consistent with the argument that remittances permit households to make high-value investments that pay off over a longer time horizon. Specifically, out-migrant remittances have a significant positive effect on the area in forest (proportion) and perennials (proportion and area), as well as a marginally significant negative effect on the area in pasture (proportion). Keeping in mind that monetary remittances are relatively rare in this population, we see evidence that when they are received they permit families to expand their area in perennials. Essential for understanding the importance of remittances is the time to return on investment in perennials. Cacao trees do not produce a marketable crop for approximately the amount of time over which we observe land-use change. Thus, we suggest that the remittances may help the family to maintain their standard of living while investing labor (and money) in cacao before it begins to pay for itself. This is not the case for the shorter-return pasture production.

Figure 2 compares the labor effect and remittance effect visually by plotting the predicted proportion of the property in perennials or pasture in 2005 as a function of the number of out-migrants transferring, separately by the number of out-migrant children.Footnote 11 Line A represents the increase in the proportion of perennials with 1 additional out-migrant child transferring, while line B represents the reduction in the proportion of property in perennials with the leaving of one child. A clearly dwarfs B, suggesting that, even if out-migration was significantly negatively related to decline in perennials, remittances would more than compensate for the lost labor when a child leaves the household. For pasture, the area in fact increases by B with every additional migrant, but again the remittance effect outweighs the migration effect so there is a net decline in area in pasture for each additional out-migrant who remits.

Discussion and conclusions

Migrant selectivity in the context of an aging frontier follows patterns expected based on literature from around the world; migrants come from households with plentiful labor (more adults) and with more productive area (as opposed to forest). Importantly, this points to a transition from the early subsistence logic among settlers posited by household life cycle models based on Chayanovian peasant household models (McCracken et al. 1999, 2002). It confirms the transition to a market-oriented productive system (Caldas et al. 2007), in which perennials and pasture are economically important and appear to measure household wealth in our models. While this finding is not surprising in a region that is well-integrated to regional economic markets, the consequences of that migration for rural land use were less clear-cut prior to analysis.

First, second generation out-migrants may be excess labor on the farm, suggesting that their departure will have no impact on the farm, or they may be needed on-farm but see better opportunities elsewhere, suggesting their departure will decrease the ability of the farm to maintain production without hired labor (and potentially will slow deforestation and encourage forest regrowth). Our results suggest that migrants were excess labor on the farm or that they maintain their contribution to the farm, as out-migration has no significant impact on land uses. Second, literature on the remittance economy worldwide points to two opposite predictions; remittances may allow aging parents to purchase food as a substitute for on-farm production, leading to a contraction of productive area (Adams 2006; Davis and Lopez-Carr 2010), or remittances may allow investment in new products or technologies, leading to expansion of some crops, particularly those that require longer investment or are riskier (Yang and Choi 2007; Gray 2009; Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010). Our results suggest the latter function of remittances. While remittances do have a marginally significant positive effect on the proportion of the property in forest and a marginally significant negative effect on the proportion in pasture, the most consistent and largest effect is the positive effect on the area or proportion of the property in perennials.

This work links to broader arguments about the future of people and forests in the Amazon. While we do not see the optimistic future for forests that might be expected in the Forest Transition Theory, in which out-migration means a transfer of labor from the rural to the urban and a regrowth of forest (Rudel et al. 2005; Robson and Nayak 2010), we do have some optimism for the future. Remittances are still rare in our study area, with only 12% of households in our sample receiving money. They appear, however, to be protective of forest and to encourage investment in capital-intensive perennials production in place of extensive pasture formation. Thus, a combination of opportunities for migrants that would provide adequate income to remit with promotion of settlements in areas where high-value and relatively capital-intensive crops or agrarian activities are possible has the potential to protect forest and improve rural livelihoods. We suggest that both are necessary components to avoid the extensive and destructive conversion of primary forest to low productivity pasture. Families will make an investment if there is a potential for that investment to pay off, in this case appropriate soils and local institutional infrastructure to get cacao to market, and if the needed capital can be acquired, in this case through remittances. The basic story should generalize to value-added production of eggs or processed poultry, or of frozen fruit pulp, and to capital accessed through credit, grants, or local off-farm employment. Whether it in fact does generalize we cannot know without looking to these other cases in the Amazon and elsewhere.

This research program, begun in one place in the Amazon in this paper, is an essential piece of the puzzle of the future of agrarian reform settlements in the Brazilian Amazon and small-farmer frontiers around the world. If families can maintain productive land uses in the face of out-migration of children and can potentially move into more profitable market-oriented production through remittances, frontiers are less likely to experience rapid land consolidation, rising inequality, and mechanized agriculture, with its attendant environmental and demographic impacts (Hogan et al. 2001, 2008). While we do see substantial levels of out-migration of adult children, as we would in a traditional rural exodus and urbanization story, our results suggest that migrants’ remittances may function as a form of subsidized credit to reduce future pressure on urbanization by fixing population in rural areas (Hogan 1992, 2005), as well as by facilitating the increase in rural households’ well-being (Barbieri et al. 2009; VanWey et al. forthcoming).

Notes

The first phase of migration into the Amazon was primarily motivated by government policies aimed at preserving Amazonian sovereignty and reducing pressure for agrarian reform. Some studies suggested that the likelihood of a small farmer succeeding in the Amazon was much higher than in other parts of the country (FAO/UNDP/MARA 1992). The second phase of migration, rural–rural and rural–urban migration flows within the Amazon, added to the fast-growing local urban centers and reflected small-scale farmers diversifying their portfolio of capitals over space. This spatial diversification of capitals resulted in a growing number of multi-sited households in the region (Padoch et al. 2008).

Data from the Brazilian Demographic Census, for instance, reveal that inter-regional rural–rural migration (from elsewhere to the North Region) gave way to rural–urban, as well as urban–urban intra-regional migratory streams from the 1990s on (Hogan et al. 2008).

A strong test requires an analysis of the migration behavior of each individual adult child, examining the coordination or competition between them in both migration behaviors and remittances. Such analyses would distract from our primary focus on the bidirectional relationship between land use and migration. A strong test further requires detailed information about the income of migrants in their destinations, which is not present in our data.

We allowed the respondents to use their own definitions of urban and rural, but in cases where they asked, we used the definition of urban and rural used by IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). This defines the urban population as households or persons living in the areas corresponding to the municipality seats (urbanized or not) or villages (district seats). The rural population corresponds to the rest of population living in the other areas within the municipality political and administrative boundaries (IBGE 2010).

For those producing (only for sale), but with no information about the amount, we assigned them the same production as a randomly selected other respondent (selected from among others who produced that same product). For those with missing information about the price of products sold (including those for whom we imputed production values and those only missing information on prices), we assigned them the same price received by a randomly selected other respondent (selected from others who sold the same crop).

We lose 10 households from this sample of 277 because there was no information about property size and land use for 4 cases, 3 households had no children (and thus were not at risk of the out-migration of coresident children), and 3 had missing information about financial transfers from children.

We use SUR models to account for correlation among residuals of land use equations. This is the case when land use classes are measured within the same unit (property). Therefore, change in one land use will be correlated with change in the other land use classes (Guedes 2010).

We used a Heckman selection model (results available upon request) to test whether there was a significant correlation between land use in 2005 and selection into property size change. The Wald test of independence between outcome (land use/cover classes) and selection (change in property size) equations was not significant for the outcomes used.

The command for seemingly unrelated regression equations in Stata MP 11.0 (StataCorp 2009) does not allow for bootstrap standard errors, but it allows the use of an alternate divisor in computing the covariance matrix for the equation residuals, adjusted for small samples. When this option is chosen, a small-sample adjustment is made and the divisor is taken to be \( \sqrt {\left( {n - k_{i} } \right)\left( {n - k_{j} } \right)} \), where k i and k j are the numbers of parameters in equations i and j, respectively (StataCorp 2009).

In addition, there is evidence in our study area that the net financial transfers tend to be zero, followed by transfers from the household to the non-coresident children (Guedes et al. 2009b).

Estimated values hold the other variables from the Tobit model constant at their mean value.

References

Adams, R. (2006). International remittances and the household: Analysis and review of global evidence. Journal of African Economics, 15, 396–425.

Barbieri, A. F., & Carr, D. L. (2005). Gender-specific out-migration, deforestation and urbanization in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Global and Planetary Change, 47(2–4), 99–110.

Barbieri, A. F., Carr, D. L., & Bilsborrow, R. E. (2009). Migration within the frontier: The second generation colonization in the ecuadorian Amazon. Population Research and Policy Review, 28(3), 291–320.

Browder, J. O. (2002). The urban-rural interface: Urbanization and tropical forest cover change. Urban Ecosystems, 6(1–2), 21–41.

Browder, J. O., & Godfrey, B. J. (1997). Rainforest cities: Urbanization, development, and globalization of the Brazilian Amazon. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Caldas, M., Walker, R., Arima, E., Perz, S., Aldrich, S., & Simmons, C. (2007). Theorizing land cover and land use change: The peasant economy of Amazonian deforestation. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 97(1), 86–110.

D’Antona, A. O., VanWey, L. K., & Hayashi, C. M. (2006). Property size and land cover change in the Brazilian Amazon. Population and Environment, 27(5–6), 373–396.

Davis, J., & Lopez-Carr, D. (2010). The effects of migrant remittances on population–environment dynamics in migrant origin areas: International migration, fertility, and consumption in highland Guatemala. Population & Environment, Original Paper. doi:10.1007/s11111-010-0128-7.

De Brauw, A., & Rozelle, S. (2008). Migration and household investment in rural China. China Economic Review, 19(2), 320–335.

Ellis, F. (1998). Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. Journal of Development Studies, 35(1), 1–38.

FAO/UNDP/MARA. (1992). Principais indicadores sócio-econômicos dos assentamentos de reforma agrária. Brasília: FAO/PNUD/MARA. Projeto BRA-87/022.

Feliciano, C. (2005). Educational selectivity in U.S. immigration: How do immigrants compare to those left behind? Demography, 42(1), 131–152.

Gonçalves, S., & White, H. (2005). Bootstrap standard error estimates for linear regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 100(471), 970–979. doi:10.1198/016214504000002087.

Gray, C. (2009). Rural out-migration and stallholder agriculture in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Journal of Population & Environment, 30, 193–197.

Guedes, G. R. (2010). Ciclo de Vida Domiciliar, Ciclo do Lote e Dinâmica do Uso da Terra na Amazônia Rural Brasileira—Um estudo de caso para Altamira, Para. Ph.D. Disseration, Demography Department, CEDEPLAR/Federal University of Minas Gerais, 223 pp.

Guedes, G. R., Costa, S., & Brondízio, E. S. (2009a). Revisiting the hierarchy of urban areas in the Brazilian Amazon: A multilevel approach. Population and Environment, 30(4–5), 159–192.

Guedes, G. R., Queiroz, B. L., & VanWey, L. K. (2009b). Transferências intergeracionais privadas na Amazônia rural Brasileira. Nova Economia, 19(2), 325–357.

Guedes, G. R., Resende, A. C., Brondizio, E. S., D′Antona, A. O., Penna-Firme, R. P., & Cavallini, I. (2009c). Poverty dynamics and income inequality in the eastern Brazilian Amazon. In: XXVI IUSSP international population conference, Marrakesh, Morocco.

Harris, J. R., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis. The American Economic Review, 60(1), 126–142.

Hogan, D. J. (1992). The impact of population growth on the physical environment. European Journal of Population, 8(2), 109–123.

Hogan, D. J. (1995). Population and environment in Brazil: A changing Agenda. In J. I. Clarke & L. Tabah (Eds.), Population, environment, development interactions (pp. 245–252). Paris: Cicred-Paris.

Hogan, D. J. (1998). Mobilidade populacional e Meio Ambiente. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População, 15(2), 83–92.

Hogan, D. J. (2001). Population mobility and environment. In D. J. Hogan (Ed.), Population change in Brazil: Contemporary perspectives (Vol. 1, pp. 213–223). Campinas, SP: MPC Artes Gráficas em Papel.

Hogan, D. J. (2005). Mobilidade populacional, sustentabilidade ambiental e vulnerabilidade social. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População, 22(2), 323–338.

Hogan, D. J., Cunha, J. M. P., & Carmo, R. L. (2001). Land use and land cover change in Brazil’s Center-West: Demographic, social and environmental consequences. In: Hogan, D. J. (Ed.). Population change in Brazil: Contemporary perspectives. Campinas: Population Studies Center (Nepo/Unicamp) pp. 309–332.

Hogan, D. J., D’Antona, A. O., & Carmo, R. L. (2008). Dinâmica demográfica recente da Amazônia. In M. Batistella, E. F. Moran, & D. A. Alves (Eds.), Amazônia: Natureza e Sociedade em Transição (pp. 71–116). São Paulo: Edusp.

Hogan, D. J., & Marandola, E., Jr. (2005). Towards an interdisciplinary conceptualisation of vulnerability. Population, Space and Place, 11, 455–471.

IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). (2010). Banco Multidimensional de estatística. Available at: http://www.bme.ibge.gov.br.

Jokisch, B. D. (2002). Migration and agricultural change: The case of smallholder agriculture in highland Ecuador. Journal of Human Ecology, 30(4), 523–550.

Lee, E. S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1), 47–57.

Marandola, E., Jr., & Hogan, D. J. (2007). Em direção a uma demografia ambiental? Avaliação e tendências dos estudos de população e ambiente no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Estudos da População, 24(2), 1–25.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466.

Massey, D. S., Axinn, W. G., & Ghimire, D. J. (2010). Environmental change and out-migration: evidence from Nepal. Population & Environment, Original Paper. doi:10.1007/s11111-010-0119-8.

Mazzucato, V. (2009). Informal insurance arrangements in Ghanaian migrants’ transnational networks: The role of reverse remittances and geographic proximity. World Development, 37(6), 1105–1115.

McCracken, S. D., Brondizio, E. S., Nelson, D., Moran, E. F., Siqueira, A. D., & Rodriguez-Pedraza, C. (1999). Remote sensing and GIS at farm property level: Demography and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing, 65(11), 1311–1320.

McCracken, S., Siqueira, A. D., Moran, E. F., & Brondízio, E. S. (2002). Land use patterns on an agricultural frontier in Brazil: Insights and examples from a demographic perspective. In C. H. Wood & R. Porro (Eds.), Deforestation and land use in the Amazon (pp. 162–192). Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Mendola, M. (2008). Migration and technological change in rural households: Complements or substitutes? Journal of Development Economics, 85(1–2), 150–175.

Moran, E. F. (1981). Developing the Amazon. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Moran-Taylor, M. J., & Taylor, M. J. (2010). Land and leña: Linking transnational migration, natural resources, and the environment in Guatemala. Population and Environment, Original Paper. doi: 10.1007/s11111-010-0125-x.

Murphy, L. L. (2001). Colonist farm income, off-farm work, cattle, and differentiation in ecuador’s Northern Amazon. Human Organization, 60(1), 67–79.

Padoch, C., Brondizio, E., Costa, S., Pinedo-Vasquez, M., Sears, R. R., & Siqueira, A. (2008). Urban forest and rural cities: Multi-sited households, consumption patterns, and forest resources in Amazonia. Ecology and Society, 13(2), 2.

Perz, S. G. (2002). Population growth and net migration in the Brazilian Legal Amazon, 1970–1996. In C. H. Wood & R. Porro (Eds.), Deforestation and land use in the Amazon (pp. 107–129). Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Perz, S. G., Walker, R. T., & Caldas, M. M. (2006). Beyond population and environment: Household demographic life cycles and land use allocation among small farms in the Amazon. Human Ecology, 34, 829–849.

Quisumbing, A., & McNivel, S. (2010). Moving forward, looking back: The impact of migration and remittances on assets, consumption, and credit constraints in the rural Philippines. Journal of Development Studies, 46(1), 91–113.

Resurreccion, B. P., & Khanh, H. T. V. (2007). Able to come and go: Reproducing gender in female rural–urban migration in the red river delta. Population, Space and Place, 13, 211–224.

Robson, J. P., & Nayak, P. K. (2010). Rural out-migration and resource-dependent communities in Mexico and India. Population & Environment, Research Brief. doi:10.1007/s11111-010-0121-1.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Stark, O. (1989). Consumption, smoothing, migration, and marriage–evidence from rural India. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 905–926.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Wolpin, K. I. (1993). Intergenerational support and the life-cycle incomes of young men and their parents: Human capital investments, coresidence, and intergenerational financial transfers. Journal of Labor Economics, 11(1), 84–112.

Rudel, T. K., Coomes, O. T., Moran, E., Achard, F., Angelsen, A., Xu, J. C., et al. (2005). Forest transitions: Towards a global understanding of land use change. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 15(1), 23–31.

Sana, M., & Massey, D. S. (2005). Household composition, family migration, and community context: Migrant remittances in four countries. Social Science Quarterly, 86(2), 509–528.

Smith, N. J. H. (1982). Rainforest corridors: The transamazon colonization scheme. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stark, O. (1991). The migration of labor. Cambridge, USA; Oxford, UK: B. Blackwell.

Stark, O., & Lucas, R. E. B. (1988). Migration, remittances, and the family. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 36(3), 465–481.

StataCorp. (2009). Stata: Release 11. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Taylor, J. E., Rozelle, S., & de Brauw, A. (2003). Migration and incomes in source communities: A new economics of migration perspective from China. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 52(1), 75–101.

Todaro, M. P. (1969). A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. The American Economic Review, 59(1), 138–148.

VanWey, L. K. (2005). Land ownership as a determinant of international and internal migration in Mexico and internal migration in Thailand. International Migration Review, 39(1), 141–172.

VanWey, L. K., D’Antona, A. O., & Brondizio, E. S. (2007). Household demographic change and land use/land cover change in the Brazilian Amazon. Population and Environment, 28(3), 163–185.

VanWey, L. K., Guedes, G. R., & D’Antona, A. O. (2008). Land use trajectories after migration and land turnover. In Population association of America. New Orleans, LA.

VanWey, L. K., Hull, J. R., & Guedes, G. R. (forthcoming). Capitals and context: Bridging health and livelihoods in smallholder frontiers. In K. Crews-Meyer & B. King (Eds.), The politics and ecologies of health.

Walker, R. T. (2003). Mapping process to pattern in the landscape change of the Amazonian frontier. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(2), 376–398.

Walker, R. T., Moran, E. F., & Anselin, L. (2000). Deforestation and cattle ranching in the Brazilian Amazon: External capital and household processes. World Development, 28(4), 683–699.

Walker, R. T., Perz, S., Caldas, M., & Silva, L. G. T. (2002). Land use and land cover change in forest frontiers: The role of household life cycles. International Regional Science Review, 25(2), 169–199.

World Bank. (2008). World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Wouterse, F., & Taylor, J. E. (2008). Migration and income diversification: Evidence from Burkina Faso. World Development, 36(4), 625–640.

Yang, D., & Choi, H. (2007). Are remittances insurance? Evidence from rainfall shocks in the Philippines. World Bank Economic Review, 21(2), 219–248.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

VanWey, L.K., Guedes, G.R. & D’Antona, Á.O. Out-migration and land-use change in agricultural frontiers: insights from Altamira settlement project. Popul Environ 34, 44–68 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0161-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0161-1