Abstract

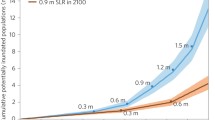

Significant advances have been made to understand the interrelationship between humans and the environment in recent years, yet research has not produced useful localized estimates that link population forecasts to environmental change. Coarse, static population estimates that have little information on projected growth or spatial variability mask substantial impacts of environmental change on especially vulnerable populations. We estimate that 20 million people in the United States will be affected by sea-level rise by 2030 in selected regions that represent a range of sociodemographic characteristics and corresponding risks of vulnerability. Our results show that the impact of sea-level rise extends beyond the directly impacted counties due to migration networks that link inland and coastal areas and their populations. Substantial rates of population growth and migration are serious considerations for developing mitigation, adaptation, and planning strategies, and for future research on the social, demographic, and political dimensions of climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 10 m low elevation coastal zone defined by McGranahan et al. (2007) represents an upper bound for defining populations at risk for inundation. Throughout this paper, we take a more conservative approach by defining at-risk areas as those susceptible to a 1-4 m increase in sea level.

The metropolitan areas susceptible to inundation include Portland, Maine; Boston, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; New York and the greater New York metro area, including Long Island; Wilmington, Delaware; Baltimore, Maryland; Norfolk-Hampton, Virginia; Charleston, South Carolina; Savannah, Georgia; Miami, Jacksonville, Fort Myers, St. Petersburg, and Pensacola, Florida; Mobile, Alabama; New Orleans, Louisiana; Oakland, San Francisco, and Sacramento, California; and Seattle, Washington.

In its most general meaning, vulnerability implies ‘‘susceptibility to loss or harm’’ (Eakin and Luers 2006).

References

Branshaw, J., & Trainor, J. (2007). The sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a modern catastrophe. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Brodie, M., Weltzien, E., Altman, D., Blendon, R. J., & Benson, J. M. (2006). Experiences of hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston shelters: Implications for future planning. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1402–1408.

Dobson, J. E., Bright, E. A., Coleman, P. R., & Worley, B. A. (2000). LandScan: A global population database for estimating populations at risk. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 66, 849–857.

Eakin, H., & Luers, A. (2006). Assessing the vulnerability of socio-environmental systems. Annual Review of Environmental Resources, 31, 365–394.

Finch, C., Emrich, C. T., & Cutter, S. L. (2010). Disaster disparities and differential recovery in New Orleans. Population and Environment, 31, 179–202.

Frey, W. H., & Singer, A. (2006). Katrina and Rita impacts on Gulf Coast populations: First census findings. Washington, DC.

Fussell, E., Sastry, N., & Vanlandingham, M. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status, and return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Population and Environment, 31, 20–42.

Goldenberg, S. B., Landsea, C. W., Mestas-Nunez, A. M., & Gray, W. M. (2001). The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity: Causes and implications. Science (New York, NY).

Grübler, A., et al. (2007). Regional, national, and spatially explicit scenarios of demographic and economic change based on SRES. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 74, 980–1029.

Gutierrez, B. T., Williams, S. J., & Thieler, E. R. (2007). Potential for shoreline changes due to sea-level rise along the U.S. Mid-Atlantic region. U.S. Geological Survey Report Series 2007-1278, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Gutmann, M. P., & Field, V. (2010). Katrina in historical context: environment and migration in the U.S. Population and Environment, 31, 3–19.

Homer, C., Huang, C., Yang, L., Wylie, B., & Coan, M. (2004). Development of a 2001 national land-cover database for the United States. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 70, 829–840.

Hori, M., & Schafer, M. J. (2009). Social costs of displacement in Louisiana after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Population and Environment, 31, 64–86.

Iceland, J. (2006). Poverty in America (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report. (2007). Synthesis report. Geneva, Switzerland.

King, S. L., Sharitz, R. R., Groninger, J. W., & Battaglia, L. L. (2009). The ecology, restoration, and management of southeastern floodplain ecosystems: A synthesis. Wetlands, 29, 624–634.

Knabb, R. D., Rhome, J. R., & Brown, D. P. (2006). Tropical cyclone report: Hurricane Katrina. National Hurricane Center.

Lutz, W., Goujon, A., Samir, K. C., & Sanderson, W. (2007). Vienna yearbook of population research 2007. Vienna, Austria: Vienna Institute of Demography.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McGranahan, G., Balk, D., & Anderson, B. (2007). The rising tide: Assessing the risks of climate change and human settlements in low elevation coastal zones. Environment and Urbanization, 19, 17–37.

Meehl, G.A., et al. (2007). Global climate projections. In Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Meier, M. F., et al. (2007). Glaciers dominate eustatic sea-level rise in the 21st century. Science, 317, 1064–1067.

Mulligan, M. (2007). Global sea level change analysis based on SRTM topography and coastline and water bodies dataset (SWBD). URL: http://www.ambiotek.com/sealevel.

Myers, C. A., Slack, T., & Singelmann, J. (2008). Social vulnerability and migration in the wake of disaster: The case of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Population and Environment, 29, 271–291.

National Science Foundation. (2009). NSF solving the puzzle: Researching the impacts of climate change around the world 2009.

O’Neill, B. C., MacKellar, F. L., & Lutz, W. (2001). Population and climate change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Perry, M. J. (2006). Domestic net migration in the United States: 2000 to 2004. Washington, DC.

Plyer, A., Bonaguro, J., & Hodges, K. (2010). Using administrative data to estimate population displacement and resettlement following a catastrophic U.S. disaster. Population and Environment, 31, 150–175.

Rowley, R. J., Kostelnick, J. C., Braaten, D., Li, X., & Meisel, J. (2007). Risk of rising sea level to population and land area. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 88, 105.

Schneider, A., Friedl, M. A., & Potere, D. (2009). A new map of global urban extent from MODIS satellite data. Environmental Research Letters, 4, 044003.

Shryock, H. S., & Siegel, J. S. (Eds.). (1980). The materials and methods of demography. Washintgon, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Siegel, J. (2002). Applied demography: Applications to business, government, law and public policy. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Small, C., & Cohen, J. (2004). Continental physiography, climate, and the global distribution of human population. Current Anthropology, 45, 269–277.

Sugarman, P. (1998). Sea-level rise in New Jersey. Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Geological Survey.

Titus, J. G., & Richman, C. (2001). Maps of lands vulnerable to sea level rise: Modeled elevations along the US Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Climate Research, 18, 205–228.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2001a). 2000 Census of Population and Housing: Summary File 1 United States.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2001b). Census 2000 Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary Files.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2001c). ESCAP II: Demographic analysis results. Executive steering Committee for A.C.E. Policy II, Report No. 1, October 13, 2001, Washington, DC.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2002). 2000 Census of Population Modified Race Data Summary File.

U.S. Census Bureau [producer]. (2003). Census of Population and Housing, 2000 [United States]: County-to-County Migration Flow Files [computer file].

U.S. Census Bureau Population Division. (2008). 2008 County Population Estimates.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service. (2007). Florida Census of Agriculture.URL:http://nass.usda.gov/fl.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service. (2008). California Agricultural Statistics. URL:http://nass.usda.gov/ca.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2001a). Multiple causes of death of ICD-9 Data, 1990–2000.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2001b). Natality detail data, 1990–2000.

Voss, P. R., McNiven, S., Hammer, R. B., Johnson, K. M., & Fuguitt, G. V. (2004). County-specific net migration by five-year age groups, Hispanic origin, race and sex 1990–2000. Working paper 2004–24. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Warner, K., Ehrhart, C., de Sherbinin, A., Adamo, S., & Chai-Onn, T. (2009). In search of shelter: Mapping the effects of climate change on displacement and migration.

Webster, P. J., Holland, G. J., Curry, J. A., & Chang, H.-R. (2005). Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment. New York, NY: Science.

Williams, D. R., & Collins, C. (1995). U.S. socioeconomic and racial differences in health: patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 349–386.

Young, M. H., Mogelgaard, K., Hardee, K. (2009). Projecting population, projecting climate change population in IPCC scenarios. Population (English Edition).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds to Curtis from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Graduate School and by the Wisconsin Agricultural Experiment Station. The authors wish to acknowledge Paul Voss, Jennifer Huck, and Bill Buckingham of the Applied Population Laboratory for technical assistance, Jack DeWaard for invaluable research assistance, and Halliman Winsborough, the editor, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curtis, K.J., Schneider, A. Understanding the demographic implications of climate change: estimates of localized population predictions under future scenarios of sea-level rise. Popul Environ 33, 28–54 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0136-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0136-2